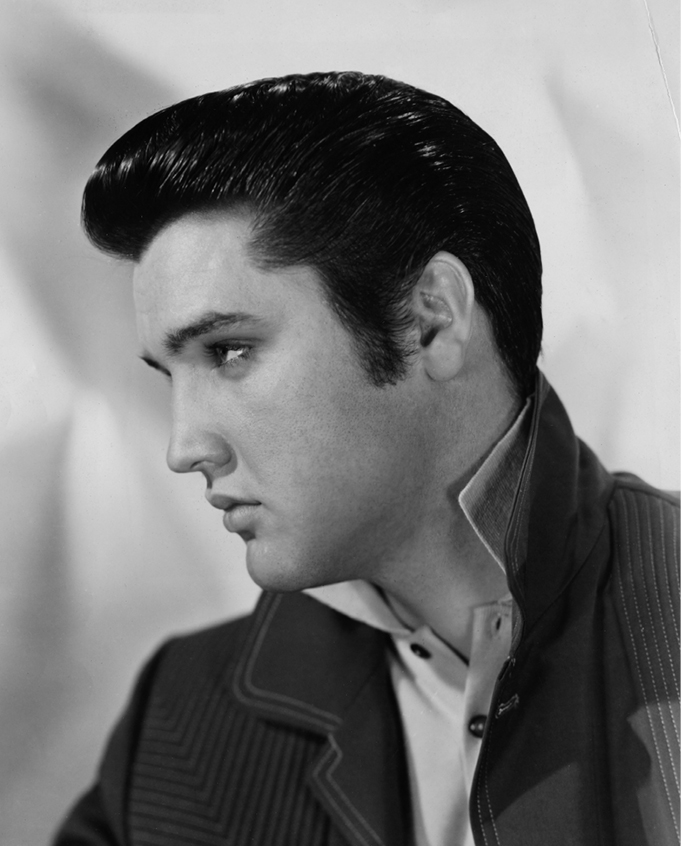

John Springer Collection / Corbis

CHAPTER FOUR

HEARTBREAK

HOTEL

The Art and Artifice of

Elvis Presley

Nashville, January 10, 1956

Rock and roll may BE meticulously choreographed insincerity, like that’s what it is (for all else it might sometimes be) . . .

RICHARD MELTZER, A Whore Just Like the Rest

In April [1956] came a song that overwhelmed everybody. . . . It was no use at all for jiving. It spoke only of loneliness and despair. Its melody was all stealth, its gloom comically overstated. He loved it all, the forlorn, sidewalk tread of the bass, the harsh guitar, the sparse tinkle of a barroom piano, and most of all the tough, manly advice with which it concluded: “Now if your baby leaves you, and you’ve got a tale to tell, just take a walk down Lonely Street . . .” For a time AFN [Armed Forces Network] was playing “Heartbreak Hotel” every hour. The song’s self-pity should have been hilarious. Instead, it made Leonard feel worldly, tragic, bigger somehow.

IAN MCEWAN, The Innocent

ELVIS PRESLEY wasn’t feeling very heartbroken when he recorded “Heartbreak Hotel.” He’d never worked in the RCA studio before, but he wasn’t scared. He had turned twenty-one just two days earlier, he had a single, “I Forgot to Remember to Forget,” climbing to the top of the country charts, and the guys he’d been playing with for months were in the studio with him. A month ago he had told an audience, “This is going to be my first hit,” before breaking into the song, which he’d first heard a month before that. Now he was brimming with enthusiasm and confidence, having just careened through a wild version of Ray Charles’s “I Got a Woman.” It was almost the exact opposite from the situation in which a nameless Miami man had found himself a year earlier—a man whom Elvis was about to pretend to be.

Sometime in 1955, an aspiring songwriter named Tommy Durden had met with Mae Axton, a Florida schoolteacher who worked as a music promoter in her spare time, in order to enlist her help with a song. He showed her a recent story in a Miami newspaper about, as Axton wrote later, “a man who had rid himself of his identity, written a one-line sentence, ‘I walk a lonely street,’ and then killed himself.” Somehow Heartbreak Hotel appeared at the end of that street, and the song that would define Elvis’s career came into being.

But there was one thing Elvis did have in common that day with the suicide who had so haunted Durden—they had both erased their identities. The suicide had done so, I assume, by getting rid of any documents that might have identified him; Elvis did so by pretending not just that his baby had left him and he was so lonely he could die, but that he was a half-crazed, hopped-up, libidinous equivalent of the movie stars—James Dean, Marlon Brando, Richard Widmark—who were capturing his and his generation’s imagination. In truth, he was a soft-spoken, well-mannered Southern kid (of the poor white rather than genteel variety) with no particular anguish tormenting him. But he, unlike the honchos at RCA—who unanimously disapproved of Elvis’s choice of song for his first major-label single—knew what his audience needed. He had seen the movies The Wild One, Rebel Without a Cause, The Blackboard Jungle, and others over and over again, and he knew that only souls in torment could light up the screen with the kind of menace that would have girls wetting their panties. “I’ve made a study of Marlon Brando,” he confided to Lloyd Shearer a few months later. “I’ve made a study of poor Jimmy Dean. I’ve made a study of myself, and I know why girls, at least the young ’uns, go for us. We’re sullen, we’re brooding, we’re something of a menace. I don’t understand it exactly, but that’s what the girls like in men. . . . You can’t be sexy if you smile. You can’t be a rebel if you grin.”

IN THE FIVE SINGLES Elvis had cut prior to this session, all for Sun Records in Memphis, he had gradually transformed himself from a naïve crooner to one of the most original—and bizarre—vocalists of his era. There had been an extraordinary evolution in Elvis’s voice through these singles: “That’s All Right,” “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” “Milkcow Blues Boogie,” “Baby Let’s Play House,” and “I Forgot to Remember to Forget.” On the first of these numbers, a bluesy R&B song from the 1940s, Elvis sang in a straightforward if ingenuous manner, sprightly and energetic, melodious and not terribly idiosyncratic. In “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” he first attempted the hoarse shout common to black bluesmen. In his October 1954 appearance on the radio show Louisiana Hayride, he added a few extra wild touches to his Sun songs. But by April 1955, the date of “Baby Let’s Play House” (his first national hit record, though only a minor success), Elvis had lost all his ingenuousness and sounded certifiably Martian, singing a baritone baby-talk with a hypnotic stutter and a vibrato that would have made Sarah Vaughan blush.

As for “Heartbreak Hotel,” it sounded like it was recorded underwater, with Elvis’s repeated gurgle of “be so lonely, baby”—a vocalism that can only have been influenced by Vincent Price—undulating over the sparsest instrumentation for a number-one hit since the musician’s strike of 1943.

What Elvis came up with in his vocal style in 1955 and 1956 was as revolutionary as what Louis Armstrong had come up with in the twenties, what Hank Williams had come up with in the forties, or what Ray Charles had come up with at roughly the same time as Elvis: a unique vocal vocabulary. Most of its major features may be heard in slightly less exaggerated form in the stylings of Clyde McPhatter of the Drifters, especially on their 1953 hit “Money Honey,” which Elvis also covered at his first RCA session; but there was something new here, a kind of parody, even self-parody, an overstatement that justified Elvis’s famous remark, “I don’t sound like nobody.” The main ingredients of this vocabulary were two completely distinct approaches to the upper and lower registers: a baritone quaver that sounded like someone was pounding him in the chest, and a tenor so pure it was ghostly. This mixture was peppered with a hiccup even more abrupt than Hank Williams’s patented my-voice-is-crackin’-’cause-I’m-cryin’ (indulged most famously in “Lovesick Blues”), an ease with blue notes that few other white singers had ever displayed, and an amplification of every sentiment into “shameless melodrama,” as Greil Marcus puts it.

At one point in his book, Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley, Peter Guralnick describes Elvis’s voice well: “‘Baby Let’s Play House’ virtually exploded with energy and high spirits and the sheer bubbling irrepressibility that Sam Phillips had first sensed in Elvis’ voice. ‘Whoa, baby, baby, baby, baby, baby,’ Elvis opened in an ascending, hiccoughing stutter that knocked everybody out with its utterly unpredictable, uninhibited, and gloriously playful ridiculousness.”

Marcus calls “Baby Let’s Play House” “a correspondence course in rock’n’roll, and it was by far the most imitated of his first records.” Virtually every white rock’n’roll—or rockabilly, which amounted to the same thing—singer of the 1950s adopted at least some of Elvis’s peculiar mannerisms. As Stephen Tucker puts it, “They sang most often with a strong southern accent complemented by a gaggle of vocal gymnastics—hiccuping, gliding into a lower register, swooping up to a falsetto, growling, howling, and stuttering.” At Sun Records, there were Roy Orbison, Charlie Rich, Carl Perkins, Billy Lee Riley, and Warren Smith; elsewhere, there were Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent, Wanda Jackson, George Jones, and dozens of other little Elvises mushrooming across America. And the key thing about them all was their “utterly unpredictable, uninhibited, and gloriously playful ridiculousness.” Buddy Holly hiccupped nursery rhymes, Jerry Lee Lewis played Satan, and from “Ubangi Stomp” to “Flying Saucers Rock ’n’ Roll,” they all reveled in other worlds. As Sun’s publicist Bill Williams put it, “All of ’em were totally nuts. I think every one of them must have come in on the midnight train from nowhere. I mean, it was like they came from outer space.” Beamed here by an Elvis ray, one supposes, for Elvis’s otherworldly voice spawned rockabilly in the same way that Charlie Parker’s saxophone spawned bebop or Jimi Hendrix’s guitar spawned hard rock.

LAST TRAIN TO MEMPHIS is likely to remain the most authoritative book on Elvis Presley’s early life for a long time. It’s a remarkable work not only for its startlingly vivid evocation of a bygone age and landscape but because it finally cleared up many of the paradoxes surrounding Elvis’s rise.

But those paradoxes still seem puzzling, even if we now know all the facts in detail. A nineteen-year-old whose professed ambition was to be another Dean Martin suddenly reinvents rock’n’roll. Sam Phillips, head of Sun Records, who reportedly said that if he could find a white man who could sing like a black man he could make “a billion dollars,” sits on Elvis’s first acetate for a year without calling him and, after a handful of singles, sells his contract for $35,000. A talent marketed to a country-and-western audience sings primarily rhythm-and-blues numbers; an innocent, clean-cut young man is derided as a satanic pervert; a conventional balladeer at heart invents a completely new style of singing that puts sixteen-year-old girls into a sexual frenzy. Where did that voice, that style, come from? Who taught him to dress that way, sing that way, shake that way? Was he Sam Phillips’s brainchild or a sui generis genius?

The answer to most of these questions is Elvis’s conception of himself as an actor, someone who’s just playing a part. There’s no contradiction between Dean Martin and rock’n’roll if they’re both just roles. It’s clear that Sam Phillips wanted to mold Elvis to “sing like a black man,” and that Elvis didn’t want to be limited to that. He wanted to sing not just country and rhythm-and-blues, but pop music—he wanted to try on different personas, ranging from down-home country boy to respectable young man to moody rebel to sex-crazed juvenile delinquent. As Barbara Pittman, one of Elvis’s early girlfriends, told Ken Burke, “Elvis could imitate anybody. He could do Hank Snow, Dean Martin, Mario Lanza, Eddy Arnold, the Ink Spots, anybody.”

Pittman is clearly talking about Elvis’s voice, not the way he moved or acted. And that voice is the key to understanding who Elvis was, where he was going, and how he gloriously galvanized American music. Apart from the above quote about “Baby Let’s Play House,” however, Guralnick barely discusses the subject.

The world of Last Train to Memphis is, like the world in most of Guralnick’s books, one of Americans to whom music comes more or less as naturally as breathing—good Americans often defeated by the pressures of the music industry but just as often thriving despite them. In his books one rarely finds musicians who spend hours trying to perfect their technique, or struggle with self-destruction and violence, or put on different masks for different audiences; his is a largely pastoral vision of American music, at once awe-inspiring and everyday.

In his author’s note, Guralnick writes that Elvis “sang all the songs he really cared about . . . without barrier or affectation,” which makes Elvis sound like an idealized country or blues singer. In an early and enormously influential 1976 essay, “Elvis Presley and the American Dream,” Guralnick says that Elvis “never recaptured the spirit or the verve of those first Sun sessions, [which] were seriously, passionately, and joyously in earnest, . . . pure and timeless.” By contrast, the RCA sides were characterized by “musical excesses and [a] pronounced air of self-parody, [and] were also fundamentally silly records.” And in another essay, “Faded Love,” Guralnick writes that the Sun years were characterized by “a kind of unself-conscious innocence. . . . On the Sun sides he [threw] in everything that had made up his life to date.” Guralnick is essentially ignoring “Baby Let’s Play House,” Elvis’s most influential Sun side, and saying that the real Elvis was the one of “That’s All Right, Mama”—an authentic Elvis who sang from his soul and imbued his songs with his own essence.

And plenty of other writers seem to have agreed. Bobbie Ann Mason, in her short biography of Elvis, writes that “everything he did seemed so natural and real. . . . The sounds that came hurtling out of Elvis’s unfettered soul were so real and refreshing.” Pamela Clarke Keogh, who rightly points out that “Elvis was almost pure style” in her illustrated biography, goes on to say that his style “was, essentially, himself.” It is often taken for granted that any singer who can convey Elvis’s energy and passion must be singing from the bottom of the heart.

But if one listens closely, Elvis’s voice just doesn’t fit these descriptions. The most successful Sun and early RCA singles are overwhelmed by vocal tics, mannerisms, postures—and a radical new style. Perhaps Elvis’s peculiarities no longer sound like affectations because we’ve become so familiar with them, both in his own records and in those of his musical descendants; but compared to the singing of Hank Snow, Carl Smith, Eddy Arnold, Dean Martin, or Frank Sinatra, Elvis sounded completely crazy. He sounded evil.

He was neither. He knew perfectly well what he was doing. He knew how to inject a snarl into his voice, just as he knew how to put a sneer into his smile. An arrogance came across in his singing, an arrogance that was—especially when compared to the obsequiousness he displayed in interviews—an act.

THE RCA STUDIO in Nashville was in a dilapidated building, home of the United Methodist Television, Radio and Film Commission; it had, in Howard DeWitt’s words, “a dark, eerie quality to it,” most fitting for the debut of “Heartbreak Hotel.” But January 10 wasn’t the first time Elvis had been in it. He’d arrived in Nashville five days earlier to prepare for the session and to check things out. Steve Sholes, RCA’s main A&R man and Elvis’s main RCA contact, later recalled that “Elvis walked into the studio and smiled. Then he started tapping his foot as he looked around the room.”

When he came back to the studio on the afternoon of January 10, his band, the Blue Moon Boys—Scotty Moore on guitar, Bill Black on bass, and D. J. Fontana on drums—were all there. In addition, Sholes and Elvis had decided to add two other musicians for this session: famed session guitarist Chet Atkins and equally famed pianist Floyd Cramer, both well-established country musicians. Elvis still felt somewhat nervous, understandably enough. It was his first time recording outside the familiar Sun Studios, and he spent the first ten minutes pacing around the room. Finally, in order to calm down a little, he sat down next to Cramer and started playing the piano and singing spirituals—“I’m Bound for the Kingdom,” “I’ll Tell It Wherever I Go.” After that, Sholes told Elvis to choose his first song. All the nervousness was now gone, and Elvis was ready.

The set of sessions lasted nine hours—from two to five that afternoon (“I Got a Woman,” “Heartbreak Hotel”), from seven to ten that evening (“Money Honey”), and from four to seven the following afternoon (two ballads Sholes and Elvis had chosen from Sholes’s list of potential songs for the date, “I Was the One” and “I’m Counting on You”). The studio was full of observers, including Elvis’s manager, Colonel Tom Parker; Parker’s assistant, Tom Diskin; Mae Axton; and various RCA executives, trying to assess their latest acquisition.

At first, Elvis danced around the room, full of energy and good spirits. Sholes halted the taping and explained that here, unlike at Sun, Elvis needed to stand in one spot, a large “X” taped on the floor. But of course, that didn’t work at all. Sholes had the studio remiked, and now Elvis could dance around as much as he wanted. He took his shoes off, cut his finger on a guitar string, refused to take a break when Sholes suggested it, and cut take after take. He took charge, actually directing the session. Sholes was no longer calling the shots—if he ever had been. “I Got a Woman,” a song Elvis had been performing since its original release a year earlier, was recorded within an hour.

The result was nothing short of spectacular. When you listen to “I Got a Woman,” it’s almost impossible to imagine Elvis standing still. The way he was dancing around the room is audible in his voice. It’s a restless record, hopped-up and irrepressible, one of the most energetic numbers he ever recorded. The words mean nothing, less than nothing to Elvis. The whole song is about the beat, and about Elvis’s voice: its quiver, its almost Sinatra-like phrasing, stretching the phrases beyond the bar line—then chopping up the beat, feather-light one moment and dropping down to an unintelligible stutter the next. It’s a record all about playfulness and freedom, the limitless possibilities of the human voice when animated by the right groove.

“Heartbreak Hotel” was a strange contrast. Here the energy was tightly controlled; and instead of triumph, the subject of the song was utter defeat. DeWitt describes the session well: “Colonel Tom Parker was unusually quiet during the taping. Steve Sholes rubbed his neck nervously. The musicians looked bored.”

In Nashville, the usual procedure was to record four sides per three-hour session. Yet only two sides had been recorded in the afternoon session, and the entire evening session was devoted to recording “Money Honey,” a huge R&B hit in 1953, without getting a satisfactory take (the released version is spliced from two different takes). Clyde McPhatter’s version could have served as a kind of template for Elvis’s vocal style, and Elvis had been performing it live for over a year; but somehow he couldn’t capture the joy and freedom of the original.

The next day, Elvis inserted all sorts of exaggerated quivers, swoops, stutters, and even some slightly off-key notes into two pallid ballads, rendering them practically unfit for release.

SHOLES WAS NOW over a barrel. He needed to release a single to prove to his superiors at RCA that Elvis was worth the money he’d spent on him. He had been careful to steer Elvis in the right direction: a few weeks earlier, he’d sent Elvis a note proposing ten titles for the session, accompanied by lead sheets and acetate demos. These included, besides the two ballads, songs like “I Need a Good Girl Bad,” “Shiver and Shake,” “Old Devil Blues,” “Automatic Baby,” and “Wam Bam Hot Ziggety Zam.” But what Elvis had now recorded was nothing Sholes felt at all confident about: two covers of well-known R&B songs; the two ballads, which Elvis had badly mangled; and “Heartbreak Hotel.” No less an authority than Sam Phillips, Elvis’s producer at Sun, pronounced that song a “morbid mess . . . only a damned fool would release it.” Nobody seemed to like it—not Sholes, not Atkins (the nominal producer of the session), not Gordon Stoker, who had provided background vocals on the ballads. And Sholes’s superiors were so put off by the session that they wanted him to go back to Nashville. “They all told me [‘Heartbreak Hotel’] didn’t sound like anything, it didn’t sound like his other record[s], and I’d better not release it, better go back and record it again.” (The song had previously been turned down by the Wilburn Brothers too, who called it “weird”; and even Colonel Parker had been unconvinced when he’d first heard it.) In short, “Heartbreak Hotel” sounded nothing like what Elvis was supposed to sound like, and what he’d sounded like until now: vibrant, upbeat, exuberant.

On the other hand, the record perfectly captured the teenage angst that was sweeping the country. James Dean had died on September 30, 1955, and Rebel Without a Cause had opened less than a month later. Fan clubs sprang up around the world, including twenty-six in Indiana, Dean’s home state, alone. Thousands of kids tried to look, dress, and act like Dean. At least six memorial pop records were released, including “Jimmy Dean’s First Christmas in Heaven.” There was, in short, mass hysteria. And everybody was wondering who’d be the next James Dean.

With “Heartbreak Hotel,” Elvis, who knew Rebel Without a Cause by heart, proved he fit the bill perfectly. By April, the song had reached number one on Billboard’s pop and country-western charts, and number three on its R&B charts. And its almost unequaled success in crossing these genres (only two songs in American history have performed better on all three charts: Elvis’s third RCA single, “Hound Dog,” and Jerry Lee Lewis’s “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On”) was no accident. When Elvis came to RCA, he was given far more artistic freedom than he’d had at Sun, and he used that freedom with a deliberation and assurance that can only be considered astonishing coming from such a novice entertainer.

“HEARTBREAK HOTEL,” like “Baby Let’s Play House,” “Hound Dog,” and “All Shook Up,” has a meaning beyond its existence as a consumer product. These early songs helped define a new generation with a message of liberated desire; and Elvis Presley used all of his powers of exaggeration, exuberance, and bravery to create a hitherto unheard music that would, yes, change the world.

Like most innovators, Elvis Presley had a vision, a vision that continuously evolved, yet always remained true to its founding principle. At its heart was his voice, with its inimitable combination of playfulness, arrogance, and desire. Perhaps it was this mixture that set his music apart from that of his predecessors—there certainly wasn’t much arrogance in the popular music of the early 1950s, and the songs of playfulness and desire seemed to inhabit two different worlds.

This mixture not only precluded any sort of personal authenticity, it seemed to be a reaction against it. In order to make arrogance and desire palatable to American listeners, they could not be genuine; moreover, it’s difficult to be simultaneously earnest and playful (perhaps only certain hip-hop artists have pulled this off successfully). By embellishing country music’s plainspoken style with all sorts of mannerisms, Elvis deliberately moved his music away from the this-is-God’s-truth mode of country delivery and the cult of authenticity that went with it. His casual delivery and the way he slurred his words are reminiscent of Dean Martin’s later records. But while much of Martin’s charm lay in the fact that he sounded just as drunk as he appeared to be, Elvis sounded like a cartoon version of a drunk.

It only made sense, then, that the songs he and his managers chose rarely, if ever, bore any relationship to the events of his personal life—a sharp contrast to the modus operandi of Hank Williams or Jimmie Rodgers. In fact, rock’n’roll songwriting—with the exception of the songs of Leiber and Stoller, who also wrote many of the greatest rhythm and blues hits—moved away from the storytelling mode so predominant in country and rhythm and blues, adopting instead the bland ingenuousness of mass-market pop. And as for Leiber and Stoller’s records, they took the real-life situations earlier blues songs had elaborated on and injected them with a rebellious humor that made them seem cartoonish and absurd.

In other words, rock’n’roll was at its core self-consciously inauthentic music. It spoke of self-invention: if Elvis could reinvent himself, so could others; if he could assume a mask, so could anyone. Its inauthenticity gave it staying power.

Much the same could be said of a later musical phenomenon—disco. Both genres delighted in absurdity; both engendered record-smashing and unreasonable tirades from the keepers of the status quo; both reflected the tastes of marginalized social groups (hillbillies and adolescent delinquents in one case, gays and blacks in the other); both were wild, uninhibited, and explicitly rejected all previous musical genres; both made radical breaks with past styles in clothing and décor; and both ignored the idea widely accepted as central to country, blues, folk, and much of later rock music: that one’s music should reflect one’s own real life and personality and world. Instead, rockabilly and disco created their own peculiar, unique worlds, populated by cartoonish characters, lots of sex, partying, and generally uninhibited behavior.

And the cult that developed around the King, unlike the later cults of Kurt Cobain and Tupac Shakur, was fully cognizant of Elvis’s love for inauthenticity, for artifice. Would Elvis have spawned so many impersonators if he had sung just what came naturally to him, without affectations? In fact, like his voice, every other aspect of his life—the gaudiness of Graceland (which would soon become his own personal Heartbreak Hotel), his need to be surrounded by hangers-on, his drug-taking and spiritual quests, the way he twitched while he was singing, and his obsessions with police and kung-fu—seemed to be symptoms of one thing: the fear of being alone. “I’ll be so lonely, I could die.” The road of personal authenticity is a lonely one; Elvis avoided it like the plague.

And rock’n’roll largely followed in his footsteps. For the first ten years of its history, the question of authenticity was raised only by the music’s detractors.

THE MASSIVE SUCCESS of “Heartbreak Hotel” overshadowed all previous rock’n’roll—the song gave the genre a new definition, setting it apart from everything that had gone before. (Even John Lennon credited “Heartbreak Hotel” with igniting his love for the music.) But it wasn’t the playfulness of the song that accomplished this: earlier rock’n’roll hits such as “Maybelline,” “Rock Around the Clock,” and “Bo Diddley” had been playful enough. It was the song’s exaggerated melancholy, the melancholy that had so scared the brass at RCA. In his repeated “be so lonely,” Elvis was creating an unreal, artificial world, marking rock’n’roll as a genre free from introspection or confession.

As a result, rock’n’roll was shunned by those who sought authenticity: it was anathema to folk, jazz, and blues purists, not to mention the defenders of the pop-music status quo. Blues and folk scholar Jeff Todd Titon writes, “In the late 1950s when I was a teenager, . . . folk music was in vogue; it offered a meaningful musical alternative to rock and roll’s vapid insistency”; and his reaction was far from uncommon.

More contemporaneous examples are numerous. Frank Sinatra, a staunch defender of traditional jazz, wrote in 1957 that rock’n’roll “smells phony and false.” Time magazine, also in 1957, called it an “epileptic kind of minstrelsy.” The same year, Mitch Miller, the head of A&R at Columbia Records, who had made Sinatra sing ridiculous numbers like “Mama Will Bark” and “Tennessee Newsboy,” called Presley a “three-ring circus” and rock records the “comic books” of music. As late as 1964, Peter Yarrow of Peter, Paul and Mary called the typical rock’n’roller “an unscrupulous modifier of folk songs whose business it is to make this type of song palatable for the teenage delinquent mother-my-dog instinct.” (Of course, Yarrow himself was none too scrupulous a modifier of folk songs.)

The funny thing about these comments by Elvis’s hypocritical detractors is that they were all on the money. For rock’n’roll as performed by Elvis and his followers had introduced, via its perennial use of artifice, a host of brand new concepts to the American musical stage, concepts that, rather than debasing the music, helped it become fabulously entertaining: preening puerility, nonsense as heroism, a mirror-gazing joyousness, sex for preteens. None of these applied to much pop or folk music—or culture—before Elvis; but after Elvis, these concepts ruled America—and the world.

IF “HEARTBREAK HOTEL” marked rock’n’roll as a genre that delighted in inauthenticity, Ray Charles’s original version of “I Got a Woman,” along with its flip side, “Come Back Baby,” had marked the birth of soul as a music that came to define authenticity for a host of later performers. With these and subsequent singles, Ray Charles popularized a raw, bluesy style that emphasized the voice’s natural imperfections when overcome by emotion, introducing a level of personal authenticity into black music that was entirely foreign to performers such as Clyde McPhatter. Prior to that session, Charles, whose voice was far from resonant, had been performing in a smooth style indebted to Nat “King” Cole and Charles Brown. “I Got a Woman” seemed to come out of the blue. As Charles later told David Ritz,

[Around this time,] I became myself. I opened up the floodgates, let myself do things I hadn’t done before, created sounds which, people told me afterwards, had never been created before. If I was inventing something new, I wasn’t aware of it. In my mind, I was just bringing out more of me. . . . Imitating Nat Cole had required a certain calculation on my part. I had to gird myself, I had to fix my voice into position. I loved doing it, but it certainly wasn’t effortless. This new combination of blues and gospel was. It required nothing of me but being true to my very first identity.

In fact, in 1947, when he was only seventeen, Charles had recorded four songs, his very first—original piano-and-vocal blues (“St. Pete’s Blues,” “Walkin’ and Talkin’,” “Wonderin’ and Wonderin’,” and “Why Did You Go?”) that display every characteristic of his mature recordings. In other words, with “I Got a Woman,” Ray Charles had gone back to singing the blues.

So while both Ray Charles and Elvis appeared to be reinventing pop music vocal styles at the same time, founding new genres with ease and assurance, and while both of them were messing with the blues, singing songs of desire and loneliness, Ray Charles’s style was actually far older.

By saying that Ray Charles was striving for authenticity and Elvis wasn’t, I don’t mean to suggest that Ray was actually drowning in his own tears when he sang “Drown in My Own Tears,” a song whose melancholy is every bit as exaggerated as that of “Heartbreak Hotel.” Yet he actually did cry when performing this and other songs. Perhaps he was simply a better actor than Elvis.

More likely, though, his vocal style was more conducive to raw emotion—it was a style of grunts and sobs, the sounds of sex and weeping, of succumbing to deep feeling. The late classical music scholar Henry Pleasants describes how this works:

His records disclose an extraordinary assortment of slurs, glides, turns, shrieks, wails, breaks, shouts, screams and hollers, all wonderfully controlled, disciplined by inspired musicianship, and harnessed to ingenious subtleties of harmony, dynamics and rhythm. . . . It is the singing either of a man whose vocabulary is inadequate to express what is in his heart and mind or of one whose feelings are too intense for satisfactory verbal or conventionally melodic articulation. He can’t tell it to you. He can’t even sing it to you. He has to cry out to you, or shout to you, in tones eloquent of despair—or exaltation. The voice alone, with little assistance from the text or the notated music, conveys the message.

Elvis’s style, on the other hand, emphasized playfulness—witness how he delivered his high and low notes in entirely different manners—and the feelings expressed were exaggerated to the point of ridiculousness. Richard Middleton, perhaps the most astute analyst of Elvis’s vocal style, gets at the difference between Elvis and previous singers succinctly: in “Baby Let’s Play House,” what he calls Elvis’s “boogification” “is deliberately exaggerated so that it now expresses not instinctive enjoyment but self-aware technique: Elvis’s confidence in his own powers is so unquestioned as to reach the level of ironic self-presentation.”

IT CAN’T BE only a coincidence that Elvis chose to cover Ray Charles and Clyde McPhatter at his first RCA recording session—after all, he was trying to define himself as a brand new kind of singer, one for whom conventional vocal inhibitions did not exist. Clyde McPhatter represented one vocal extreme: a florid, mannered style characterized by exaggeration and heavy on vocal effects. (Charlie Gillett, writing about the Drifters’ hit “Such a Night,” describes McPhatter’s voice best: “The singer slightly overdid the ecstasy, feigning innocence of the humour in the situation yet somehow also communicating the sense that he was aware of his own ridiculousness.”) Charles represented another—a hoarse voice soaked in blues and gospel, a voice of black experience. Both sounded dynamic, wild, unconstrained, and both indulged in remarkable vocal techniques. Elvis wanted to encompass all this and more in his voice: melodrama, earthiness, blackness, power, joy.

But none of this had anything to do with who he really was at heart. Elvis didn’t see himself as another Clyde McPhatter or Ray Charles, both black singers singing for a black audience. Prior to “That’s All Right,” he’d recorded six songs of his own choosing, all of them conventional pop or country ballads written by whites, and his repertoire consisted mostly of songs made famous by white singers like Bing Crosby, Dean Martin, Eddie Fisher, Perry Como, Hank Williams, Eddie Arnold, and Hank Snow. Contrary to myth, Elvis probably did not frequent blues clubs on Memphis’s Beale Street while in high school; he was a white boy through and through.

While Elvis was only one of dozens of white artists who recorded R&B songs in the mid-1950s, by the time of “Heartbreak Hotel” he was beginning to see himself as a unique figure in popular music history. This white country boy wasn’t making black songs blander, like Pat Boone or Bill Haley. Instead, he was bringing the joy and excitement he heard in black song to white America undiluted. And the only way he could do so was to pretend to be black.

That pretense, though, had to be obvious in order to succeed. In this Elvis resembled nobody more than the performer who would personify white rock’n’roll ten years later, Mick Jagger. For both of them continued and updated an age-old tradition in American music: blackface minstrelsy.

The white minstrels who played blacks on stage seldom really tried to imitate or represent blacks. Everything they did was exaggerated as much as possible, whether it was their makeup or the lyrics of their songs and sketches. Elvis and Jagger were no different: their aim was to liberate whites from what they saw as their staid, all-too-polite manners and engage them in a kind of entertainment that personified the “primitive” qualities they saw in blacks: from the casual swagger to the unadorned leer, from the whoops of joy to the jive talk, from the “riddim” in their bones to the good times in their bottles.

The minstrel tradition is far from an unbroken one in America: its life has been characterized by any number of sudden stops and starts, transformations and collapses. What white rock’n’roll did with it was to shift it a little bit away from its most obvious referents (poor, uneducated blacks) and make it more general (Americans as a whole). Elvis, like many others both before and after him, repositioned the minstrel as an all-around entertainer, not just a parodist of a certain group of people. Elvis wanted to be all things to all people. So he shucked off many of the most obvious signifiers of stereotyped blackness that previous minstrels had employed: he didn’t blacken his face, he didn’t dress in rags, and his jokes were those of a nice southern boy, not a stuttering lazy idiot. Elvis thus freed minstrelsy from much of its racist essence—his early RCA singles were high on the R&B charts, were played on R&B radio stations, and were bought by black Americans in large numbers. He made neither black nor white music but American music that could appeal to everyone on earth with a new message of youth, liberation, desire, and joy.

And for the next ten years or so, that’s precisely what rock’n’roll did. Whether black (Little Richard, Lloyd Price, Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Jackie Wilson, James Brown) or white (Jerry Lee Lewis, the Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly, Roy Orbison, the Beach Boys), the rock’n’roll performers that immediately followed Elvis’s success all sang songs that specifically revolved around one persona: the teenager in love. There were few attempts to explore that persona in depth, though; this theme was simply an excuse to be as exuberant and ridiculous, as sexed up and charged up, as you could get. This wasn’t innocence, the way so many nostalgic commentators think of those early days. This was a music full of knowing winks, vaudeville tricks, novelty gimmicks, and sex, sex, sex.

All that would change in the mid-1960s, when the spectre of authenticity grabbed hold of the reins of this runaway genre, and rock music became what it remains today: a mode of performance characterized by a strong desire to stop acting and get real. Of course, there have been exceptions: the Rolling Stones and the Who in the 1960s, glam, art rock, and heavy metal in the 1970s, much of new wave in the 1980s. By now, though, Elvis’s aesthetic seems to have all but vanished. If a band doesn’t at least pretend to “get real” from time to time, they lose their credibility—and their fans.

As for Elvis himself, he never did get real—he remained an actor to the end. And as an actor, he was a great singer. Because he cared deeply about his performances, he put his heart and soul into the task of bringing life to songs as absurdly varied as “Bossa Nova Baby,” “It’s Now or Never,” “Old Shep,” and “Peace in the Valley.” Occasionally, we’d even seem to glimpse Elvis’s reality in his songs: “Suspicious Minds” and “Hurt” hinted, however accidentally, at Elvis’s troubles. But from “Baby Let’s Play House” and “Heartbreak Hotel” to “Burning Love” and “American Trilogy,” Elvis’s art was artifice, and it served him well.