CHAPTER 7

Taking the Lead

As researchers and policy makers examine the teacher shortage problem, they find that teacher dissatisfaction is driving teacher attrition. Teachers leave because of dissatisfaction with teaching conditions (e.g., class size and salaries), administration (e.g., lack of support, input on school decisions, or classroom autonomy), and oppressive policies, such as high-stakes testing. Indeed, the most frequently cited cause of dissatisfaction are accountability pressures due to test preparation and sanctions for low performance (Goldring et al., 2014).

The growing teacher shortage has implications for the quality of the teaching workforce due to the reliance on unqualified or under-qualified teachers filling such positions, resulting in negative impacts on student learning (Podolsky & Sutcher, 2016), especially in low-resourced, high turnover schools (Ronfeldt et al., 2013). A principal of a high-turnover school noted other negative impacts of turnover:

Having that many new teachers on the staff at any given time meant that there was less of a knowledge base. It meant that it was harder for families to be connected to the school because, you know, their child might get a new teacher every year. It meant there was less cohesion on the staff. It meant that every year, we had to re-cover ground in professional development that had already been covered and try to catch people up to sort of where the school was heading (Carroll et al., 2000).

The teacher shortage is costly because schools are constantly spending money on recruitment and professional support for new teachers without realizing the value of these investments because they leave (Darling-Hammond, 2003). When a teacher leaves a district, it increases the demand for teachers and also increases the costs of recruiting a new teacher. Researchers estimate that the cost of teacher turnover nationwide is over $8 billion dollars per year (Sutcher et al., 2019). Overall, research is making a strong case to policy makers that they must reduce teacher attrition—and do it quickly.

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the value of teachers’ work and the deep inequities embedded in our school systems. As schools recover from the COVID-19 crisis, there may be an opportunity to make the shifts necessary to build up and support the teaching workforce.

Teacher Leadership

The Teacher Leader Model Standards define teacher leadership as, “The process by which teachers, individually or collectively, influence their colleagues, principals, and other members of the school community to improve teaching and learning practices with the aim of increased student learning and achievement” (National Education Association, National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, and the Center for Teaching Quality, 2018, p. 11). Teacher leadership can be formal or informal and can be applied at any moment. We can recognize the influence we already have and create new opportunities for leadership within our current school. Or, we can look for opportunities outside of our current school, district, or community because there are so many teaching jobs available.

When teachers are given opportunities to lead, more talented candidates will be attracted to the teaching profession. Until recently, there was not much of a career ladder for teachers, other than to become part of the school administration. The growing teacher leadership movement is creating new leadership positions, thus providing a longer and more attractive career ladder. Research shows that to attract younger people to a career in teaching, the profession needs to offer decision making opportunities, supportive school cultures that cultivate collaboration and innovation, and time to engage in such activities. Younger workers are looking for high-quality feedback, professional learning, fair pay, and the opportunity to be rewarded for outstanding performance with higher pay. At the same time, these opportunities need to be afforded to the existing teaching workforce to prevent attrition.

There’s a move towards reenvisioning schools as lifelong learning communities, where everyone is a learner, including all the adults. In this model, the teacher becomes more of a facilitator of learning. The teacher is continuously learning how to facilitate students’ learning, from moment to moment, through skillful interactions, action research, and formative assessments. The students become partners in the learning process. Recognized as autonomous, they are afforded more choice of content and learning methodology, which stimulates motivation (Deci & Ryan, 2012). Students learn in collaborative teams, similar to the way adults work in the most highly skilled jobs today. By this method, we are better preparing them for the future.

In lifelong learning communities, teachers are empowered to exercise greater influence over decisions related to instructional practice. Most experienced teachers have content and pedagogical knowledge that the principal may not have. For this to model work, the principals need to feel secure and have the skills to support these new structures and processes, thus demonstrating that the teachers’ work is valued. A collaborative bond of reciprocity develops in which each supports the other’s work and both share the responsibility for the outcomes. The Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) and State Consortium on Education Leadership policy document, Performance Expectations and Indicators for School Leaders (2008) states:

Expectations about the performance of education leaders have changed and expanded considerably in the last decade, extending far beyond the traditional definitions of administrative roles. Responsibilities of education leaders now exceed what individual administrators in schools and districts can be expected to carry out alone. State and federal requirements to increase student learning necessitate a shift in leadership, from managing orderly environments in which teachers work autonomously in their classrooms to one in which administrators, teachers, and others share leadership roles and responsibilities for student learning. Research and best practices indicate the value of collaboration on shared vision, goals, and work needed to ensure that every student learns at high levels (p. 1).

Policy makers are beginning to understand that if teachers are to be held accountable for student learning, they must also have more control over the learning process. Policy makers are also recognizing that to encourage teachers to collaborate, there is a need to reevaluate compensation systems that focus on individual teachers alone: new evaluation systems that recognize and reward collaboration may be required. There is also a need to better define the teacher leader roles and their associated responsibilities, requirements, and compensation.

The Teacher Leader Model Standards consist of seven domains describing the many dimensions of teacher leadership (Teacher Leadership Exploratory Consortium, 2011):

DOMAIN I: Fostering a Collaborative Culture to Support Educator Development and Student Learning

DOMAIN II: Accessing and Using Research to Improve

Practice and Student Learning

DOMAIN III: Promoting Professional Learning for Continuous Improvement

DOMAIN IV: Facilitating Improvements in Instruction and Student Learning

DOMAIN V: Promoting the Use of Assessments and Data for School and District Improvement

DOMAIN VI: Improving Outreach and Collaboration with Families and Community

DOMAIN VII: Advocating for Student Learning and the Profession

Teacher leaders can contribute and collaborate in a variety of ways. Typically they support their colleagues’ professional learning, formally and informally, including presenting workshops, coaching, modeling, peer advocacy, and cultivating a collaborative school culture. Researchers have identified self-authoring as an important orientation in teacher leadership (Breidenstein et al., 2012). Dr. Robert Kegan (1994) describes self-authoring as follows:

It takes all of these objects or elements of its system, rather than the system itself; it does not identify with them but views them as parts of a new whole. This new whole is an ideology, an internal personal identity, a self-authorship that can coordinate, integrate, act upon, or invent values, beliefs, convictions, generalizations, ideals, abstractions, interpersonal loyalties, and intrapersonal states. It is no longer authored by them, it authors them and thereby achieves a personal authority (p. 185, italics in original).

In a sense, Kegan is referring to the ability to self-reflect and emerge from the mind traps that can hold us under their sway. Also, self-authoring is consistent with hypo-egoic states that are not as subject to the control of the “self-system.” Self-authoring is an ongoing process of lifelong learning and self-discovery, not an end point in and of itself.

The formation and facilitation of groups such as project teams, academic departments, professional learning communities (PLCs), and inquiry groups are highly valued leadership activities. The National Education Association, National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, and the Center for Teaching Quality (2018) highlight evidence for the group-process dimension of its overarching competencies. At the highest level of their rubric, the standards state: “Create new groups or using existing groups and facilitate those groups to overcome challenges and engage diverse opinions and experiences to meet objectives, solve problems, and achieve desired outcomes” (p. 17). Communication skills are highlighted in other sections. For example: “Influence other teacher leaders to build their capacity to effectively communicate and powerfully advocate with stakeholders at many levels,” and “use communication to navigate and counter multiple, and sometimes, adversarial power structures” (p. 15). Indeed, research has found that teacher group learning outcomes are improved with good facilitation (Little & Curry, 2009).

What are the impacts of teacher leadership? While the empirical literature is scant, there is some promising evidence. Two studies involving very large samples of teachers have found that leadership that is shared or distributed among teachers can lead to enhanced student performance. A study of collective leadership, defined as the democratic distribution of authority among school administrators and teachers, found a significant impact of collective leadership on student achievement on standardized tests (Leithwood & Mascall, 2008). “The influence of collective leadership was most strongly linked to student achievement through teacher motivation” (p. 554); teachers’ perceptions of collective leadership were associated with their motivation, which were associated with improved performance on student outcomes. A study of 199 schools in Canada (13,391 students in grades 3 and 6) found a significant positive impact of collective leadership on student math and reading performance (Leithwood et al., 2010).

A recent review of the teacher leadership literature found important signs of progress, but also the need for theory, clear definitions, and rigorous empirical research (Wenner & Campbell, 2017). Teacher leadership contributes to the quality of the school climate and all teachers’ feelings of empowerment. Teachers report that professional learning presented by teacher leaders contributes significantly to school change and is more relevant compared to presentations by nonteaching leaders. Teacher leaders report feeling more confident, more professionally satisfied, and more empowered. Authors of one study noted: “There has been a strong sense of purpose and satisfaction for them [teacher leaders] to realize that they are now leading the change, enjoy the autonomy for school improvement and change, and are empowered as leaders” (Chew & Andrews, 2010, p. 72). Teacher leaders report that their professional growth is enhanced by improved leadership skills and instructional skills. For example, one teacher noted: “My teaching has improved and I am constantly looking for new techniques to use with the pupils. … I constantly want to better myself and look forward to the next challenge” (Harris & Townsend, 2007, p. 171).

Redefining Teacher Professionalism

To elevate our profession, we need to reconsider our role. What kind of professional is a teacher? What role do power, autonomy, and agency play in professionalism? As discussed in Chapter 1, this question has plagued the teaching profession for most of American history. Dr. Andy Hargreaves (2000) described the evolution of teachers as professionals in terms of four historical periods: the preprofessional, autonomous professional, collegial professional, and postmodern or post-professional. These categories are associated with linear time periods since the early twentieth century and provide insight into how American society has conceptualized teachers’ work during the rise of industrialization.

During the preprofessional period, teachers were viewed as simple technicians delivering basic knowledge to their students. The view of teachers as autonomous professionals evolved during the 1960s when teachers began to gain greater agency and control over what and how they taught and their working conditions. While they won more rights, they still worked mostly in isolation with little professional help or feedback. In the 1980s, the view of teachers as a collegial professional arose. The growth of the knowledge base added a level of complexity to the demands of teaching that required greater collaboration with peers who have various areas of expertise.

When Hargreaves wrote his paper at the turn of this century, his impression was that the future would either grow toward a post-modern professionalism, drawing from both the autonomous and collegial professional models, or become post-professional—a de-professionalization of teaching, similar to the preprofessional era, where the teacher is again viewed as a technician.

There is plenty of evidence that recent reform efforts have been de-professionalizing, taking autonomy away from teachers by ordering scripted curricula and the strict use of pacing guides to control content delivery. However, a promising movement of shifting toward post-modern professionalism is gaining traction. In many places, the social organization of the school is beginning to transform away from a bureaucracy managed from the top down by an individual principal to a stakeholder-led community of learners. In this new model, collegiality and professionalism are highly valued, and teachers become the creators and reformers of the school culture. These schools, called professional development schools, are founded in the constructivist understanding of lifelong learning and distributed leadership (Spillane, 2006). All members of the community are engaged in the construction of new knowledge and understandings that reach well beyond the basic skills learning and test-based curriculum that has been tried and has failed miserably. In the professional development school, teachers learn through teaching and redesigning schools in collaboration with one another and with the students and their parents within the context of the community (Darling-Hammond et al., 1995). Teacher-leaders are engaged in decision-making as it relates to the mission, goals, operations, assessments, and scheduling, so they have a hand in creating a better teaching and learning environment. When we teachers are involved in decision-making, we have a greater sense of ownership and commitment to our profession and our community (DeFlaminis et al., 2016).

Referred to as distributed leadership (DL), this approach to leadership includes “…those activities that are either understood by, or designed by, organizational members to influence the motivation, knowledge, affect, and practice of organizational members in the service of the organization’s core work” (Spillane, 2006, pp. 11–12). In this model, leadership is embodied within all the members of the school community and all leadership activity is distributed across interactions. Indeed, the leadership practice is inherent within the interactions, rather than instantiated at the top of a hierarchical structure. This leadership model is better adapted to our rapidly changing complex school systems because it recognizes and promotes interdependence and interaction across various roles (leaders and followers) and contexts within the school. This model recognizes that these elements are part of a complex, dynamic system; leadership is fluid, and not inherently attached to a specific role or person. In this sense, distributed leadership is a way to lead from a systems and design thinking perspective. Rather than prescribing a new and more desirable form of leadership, it affirms that leadership is already distributed, just unrecognized as such. Researchers who have studied distributed leadership examine how leadership is actually accomplished in school organizations (Diamond & Spillane, 2016).

We often feel like we have little power when we actually may, and not even be aware of it. Our influence depends on the subject matter, existing relationships, history and power dynamics, and the specific situation we find ourselves in. For example, at a faculty meeting, Mr. Ricci is listening to the principal, Ms. Schwartz, explain her plans for revamping the mathematics curriculum. New to the school, Ms. Schwartz wants to try a novel method that she discovered during her graduate training. Mr. Ricci is thinking, “Oh, here we go again, a new principal with new curriculum ideas,” and he sits glumly looking down at his smartphone. He may not realize that his response to Ms. Schwartz’s presentation is influencing his peers. Following his lead, none of them show any enthusiasm for this idea, and Ms. Schwartz leaves the meeting disappointed in her leadership skills. Mr. Ricci is known for creating fun and interesting math activities, and he often shares them with his colleagues. He has become the leader when it comes to mathematics instruction. Just by sitting glumly during the meeting, he signaled that he wasn’t excited about Ms. Schwartz’s plans, and the other teachers followed suit. The faculty became restless and disengaged while Ms. Schwartz felt completely deflated. Because she was new to the school, she was unaware of his reputation among his peers. While in this situation he was clearly the leader, this was not explicitly recognized by anyone. Therefore, his leadership was not as effective as it could have been had Ms. Schwartz investigated the history of the school and discovered who led in the mathematics domain before she began to consider reform activity. Can you imagine how different that scenario would have been if she had invited him to discuss ways to improve their mathematics instruction before unilaterally choosing a path forward?

This is an example of how leadership can be shared across various roles under different situations and conditions. The practice of leadership occurs between the leader and the followers. In the scenario above, the faculty followed Mr. Ricci’s lead rather than engaging with the principal in a discussion about a new math curriculum. The distributed perspective on leadership views leadership as patterns of interactions rather than discrete linear actions (e.g., recognizing that the school is a complex system, not a simple one). It recognizes that leadership requires followers and therefore recognizes the interdependence of both roles. Followers are not viewed as subordinates, but as equal actors in a discrete interaction. DL is based on the understanding that change is a dynamic process that emerges from these interactions. It recognizes opportunities for leadership as fluid, not fixed in specific roles, existing in a constantly shifting complex context where any member of the community may act as leader, depending on the situation. This perspective can help us reflect on our school organization and enhance our understanding and practice of leadership in the complex system of the school. As explained in Part II, to effectively respond to any situation, it helps to step back and get an understanding of the bigger picture before taking action.

Looking back at the scenario, from the DL perspective Mr. Ricci was not an obstacle to Ms. Schwartz’s leadership, but an influential resource that could be more clearly and explicitly empowered to lead in the area of mathematics. To do this we must sidestep the mind traps and be mindful of what is actually occurring rather than what we think is, or should be, occurring. Indeed, when Ms. Schwartz returned to her office, she began to ruminate about her lack of leadership skills. She told herself a simple story that reinforced a fixed mindset about her own value as a leader. She held this script: Teachers are supposed to engage when a principal presents an idea. The teachers were not engaged; therefore, I am a bad leader.

Had Ms. Schwartz been familiar with design thinking, she could have applied it to this situation. Her first step would have been to get to know her teaching staff so she could empathize with their strengths, challenges, and perspectives. This could have formed the basis for diagnosing what the school might need and how to design ways to address such needs. She would have learned that the teachers’ respected Mr. Ricci for his creative math ideas, and she could have formally or informally engaged him as a leader to support school improvements. Together they could have used design thinking to examine the math curriculum, and teachers’ and students’ views on what they needed, and to develop a plan that would make use of his leadership in this area. Furthermore, with a better understanding of each of her staff members and their leadership skills, she would be better positioned to plan effective professional development activities in the future.

Distributed Leadership

As Ms. Schwartz considered how to improve her leadership skills, she came across the DL approach and read Distributed Leadership, leading expert Dr. James Spillane’s (2006) classic book on applying DL to schools. Determined to bring the DL perspective to her school, she began by spending time getting to know each teacher. She decided that one way to do this would be to take each of them, individually, out to lunch so they could have time away from the school in a more casual setting. She arranged for each teacher to have coverage so they could take a more leisurely lunch. The teachers were delighted by the invitation; they each got private time with her and had an opportunity for a longer lunch off campus.

Over the course of several months, Ms. Schwartz discovered the teachers’ current leadership roles and their potential for new roles. She created a map of the school using chart paper with the current arrangement of the classrooms and their associated teachers. After each lunch, she wrote notes about each meeting on the map. Being a very visual person, she found that this map helped her remember and integrate all she was learning. She discovered that Mr. Ricci was beloved by the staff for his creative math ideas that he was very willing to share. She learned that Ms. Rollins had art skills that the other teachers relied on, and that Ms. McGuire was the go-to person for team building activities for both students and teachers. Quickly Ms. Schwartz came to deeply appreciate the richness and diversity of her staff’s interests, skills, and expertise.

The next step was to introduce the staff to DL. After her math curriculum flop, she set up a meeting with Mr. Ricci and to engage Ms. McGuire in leading a warm-up activity at the beginning of the next faculty meeting.

“Until I had lunch with everyone, I didn’t know what a great reputation you have for creative math ideas,” she said. “I should have spoken with you first, before launching any new math initiative.”

Mr. Ricci chuckled, “I guess I didn’t realize that I had so much influence with the faculty until that meeting. Afterward, I felt bad that I had derailed your initiative with my attitude.”

Ms. Schwartz responded, “Well, it was uncomfortable, and it prompted me to question my leadership skills, but that was actually a good thing, because it led me to a new approach to school leadership that is distributed, or more fluid. It’s not like really changing leadership per se but recognizing that leadership can shift to different people, depending on the situation. Now, I recognize that you are the de facto math leader at this school, and I think it would work better if I invited you to take a more explicit leadership role rather than trying to come up with a new plan myself.”

“Well, I love math, and it’s fun to generate ideas to help kids learn, so that would be great, as long as I can fit it into my schedule,” he said.

“I’m not asking you to do anything different than what you are already doing. I’m simply recognizing your existing influence and making it explicit rather than de facto,” she replied.

Mr. Ricci thought about it for a minute and then replied, “I think I see what you mean. I’m already doing all these things, but since you didn’t know it, you didn’t realize that a teacher might already be a leader when it comes to math.”

Smiling, Ms. Schwartz said, “I’d like to share some ideas I have about bringing distributed leadership to our school community to see what you think. Maybe you could help me find a way to extend this approach to leadership to the whole staff.”

Ms. Schwartz’s enthusiasm was infectious, and Mr. Ricci began to brainstorm some ideas. Together they came up with a plan to introduce the idea to the staff and to invite them to explore ways to identify and distribute leadership more explicitly and more effectively. At the next meeting, Ms. McGuire led the faculty in a warm-up called “Yes, and.” This activity can promote design thinking by expanding possibilities and developing the habit of affirming (“Yes, and”) rather than negating (“Yes, but”). The faculty formed groups of three, and one person started by making a statement about the school. The person on the right responded, “Yes, and,” adding more information. Then the third person responds the same way, until they had gone around the circle three times. By the time they were finished, they were in a lively and playful mood. Next, Ms. Schwartz told the faculty about her experience at the earlier meeting and how she had discovered DL. She invited Mr. Ricci to share his part of the story and his enthusiasm for DL.

“I admit, I was in a sour mood. I didn’t want to have another math initiative imposed on me. At the time, I didn’t realize I had such influence with you all.” He laughed at himself and told them he felt bad for derailing the meeting. “After learning about DL, I can see that we are all leaders in one way or another.”

Ms. Schwartz began a brief introduction to DL and took questions from the teachers. By the end of the meeting, most of them were on board with this new approach. However, after years of working in a disempowering system, the teachers were not used to considering that they had much power, so it took work to transition to a more distributed leadership model.

Over time, the school began to make shifts towards teachers emerging as leaders in multiple ways. Ms. Schwartz reflected, “I had to completely change the way I was thinking about leadership, but when the whole community is empowered to lead and people take on the responsibility, it’s exciting for all of us. It relieves me of some of the responsibility, and outcomes can emerge that might never even have been considered before.”

Viewing the system through the distributed leadership lens gives us the opportunity to reevaluate our current roles and what it means to lead; we can explore new opportunities for growth and influence. By applying this approach, we recognize ways in which we are already leading, such as professional learning communities (PLCs), sports, committees, or extracurricular activities.

Typically DL teams are cross-functional. They include representatives from all the stakeholder groups, and they focus on an aspect of the school that affects everyone in some way, for example, a team that manages the school schedule or a team that focuses on parent engagement. In contrast, PLCs are primarily focused on continuous improvement in student learning, often working on a content area. They consist of collaborators who share mission, vision, values, and goals and work collaboratively to achieve common goals. Both PLCs and DL teams have the potential to promote growth in both leadership and learning. However, while leading a PLC is an extension of the teacher role, participation in a DL team can be transformative because teachers experience learning at a different level. Rather than simply acquiring teaching and leading skills, teachers feel empowered to change their school from within, and they learn how to do it. They begin to build a new identity as a transformational school leader (DeFlaminis et al., 2016).

How Teachers Become Leaders: A Model

Now that we have explored the value of teacher leadership, you may be asking yourself, “How do I become a teacher leader?” Since teaching, learning, and leadership are all very complex processes, it makes sense to apply systems thinking to the question. While I noted earlier that the empirical research and theory on teacher leadership is meager, one study examined this question by accessing teachers’ own ideas and experiences and presented a theoretical model of the development of teacher leadership based on this input (Poekert et al., 2016).

This model grew from a program evaluation of the Florida Master Teacher Initiative (FMTI), a collaboration between Miami-Dade County Public Schools and the University of Florida, funded by the U.S. Department of Education. This initiative aimed to improve instruction quality and boost student learning in grades preK-3 by supporting teachers to become leaders. The program offered support in a variety of ways, including providing an early childhood specialization certificate that teachers earn as part of a graduate degree program while continuing to work. The program also offered these graduate students leadership opportunities within schools to present new content and teaching practices in inquiry-based PLCs. Finally, the program provided opportunities for teachers to support administrators as they implemented distributive leadership.

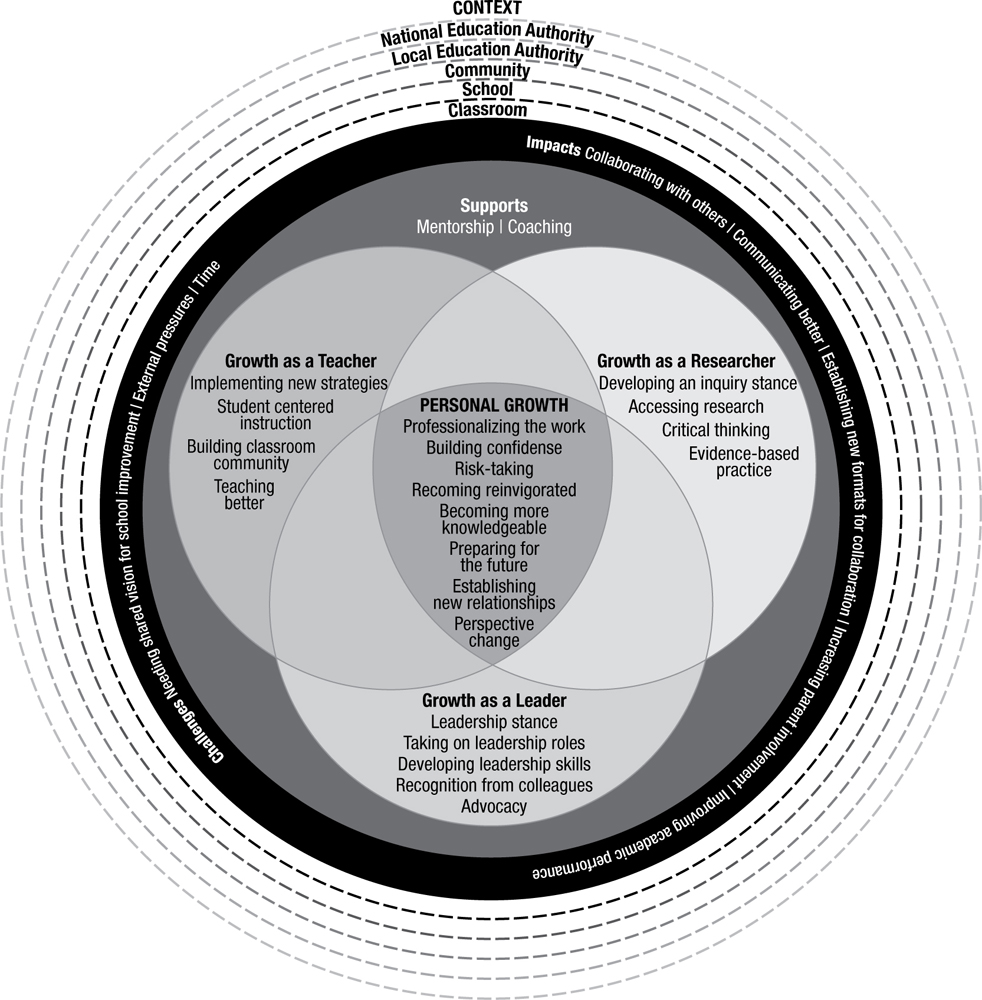

The procedure involved conducting focus group interviews with a sample of these teachers and developing a draft theory of teacher leadership. Next, the theory was refined and validated in response to participant feedback. Finally, the theory was validated in an international context, involving teacher leaders in the United Kingdom. The resulting model presents the teacher leader in the center of concentric circles representing contexts, resembling Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) model.

I like this model of teacher leadership because it takes a systems perspective on the process of teacher development, recognizing four dimensions of growth, support (mentorship and coaching), and positive impacts and challenges. The four dimensions of growth are personal growth (located in the center of the model), growth as a teacher, growth as a researcher, and growth as a leader. The layers of the environmental context include the classroom, the school, and the community. The outer layers are the local and national education authorities (e.g., departments of education). Simultaneously, teachers must interact and navigate the opportunities and challenges presented by each of these contextual layers.

For example, the annual testing regime, often imposed by the state government, directly impacts the classroom, in the form of teaching strategies; the school, in the form of potential punitive measures; and the community, in the form of the school’s reputation. As teachers build leadership skills, they find they can demonstrate positive impacts while cultivating the resilience to work through challenges. Poekert and colleagues (2016) found that the growth process was not linear, but more iterative. Teachers reported that they experienced an interdependent relationship between their own work and the responsiveness of their work environment to implement distributed leadership. Poekert and colleagues (2016) propose that teacher leadership depends on feedback loops between challenges and positive outcomes. The challenges are the barriers to becoming leaders that teachers experience; the challenges may be experienced as negative feedback but may also contribute to the teachers’ persistence and fortitude. The positive outcomes teachers experience provide positive feedback in the form of motivation and persistence.

FIGURE 7.1 A model of teacher leadership.

Source: From Poekert, P., Alexandrou, A., & Shannon, D. (2016). How teachers become leaders: An internationally validated theoretical model of teacher leadership development. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 21, 307–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2016.1226559, reprinted by permission of the publisher (Taylor & Francis, Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com).

Growth as a Teacher

The model presents four core competencies related to teacher development. The first is growth as a teacher, defined as “use of evidence informed interactional and teaching practices to improve child outcomes” (Poekert et al., 2016, p. 317). Teachers found that the model gave them a structure to view and promote their own development. One American teacher noted,

I feel almost like a new teacher when I go in with my new strategies … I know I’ve been doing something these past 18 years. But now, I’m going in and I’m building classroom community, and I’m doing all these things now that I don’t remember doing before. (Poekert et al., 2016, p. 318)

As teachers developed confidence in their ability to apply new and innovative methods, they discovered that they had more energy and confidence to engage in leadership activities. A teacher from the UK group reported,

To take on a role as a teacher leader, you need to have confidence to be able to speak to your colleagues on what you’re doing and that only comes … if you are confident in yourself as a teacher, which comes I think through teaching experience and through upskilling. (Poekert et al., 2016, p. 318)

Growth as a Researcher

The second core competency in this teacher leadership model is defined as “developing a systematic and iterative approach to improving classroom practices” (Poekert et al., 2016, p. 317). One American teacher described this process as follows:

You look at your own teaching and figure out where to improve, use research and find things people have done. You try to improve your teaching, collect data as you do it so you can see whether you are doing it or not. I did an inquiry on peer teaching—tutoring, pairing students of different abilities low and medium, medium and high, so both get something out of it. Speed and accuracy of math facts went up as a result. (Poekert et al., 2016, p. 319)

Teachers developed improved critical thinking and were more comfortable assessing their own strengths and areas for growth and critiquing their lessons, based in their research aims, which helped them refine their teaching strategies. They found validation in sharing research supporting their work to administrators and peers. Many reported that this process was empowering and motivated them to continue their leadership roles. One American teacher noted:

I’d like to think that my students had gained something over the years, but now it’s like … I know the effect that [my teaching] has on them. I can see—and that builds confidence in me. I try to build the same confidence in some of my colleagues. (Poekert et al., 2016, p. 319)

They also found that the inquiry process supported collaboration and collegiality among the staff, and because their confidence was building, they felt safer to self-reflect on their practice.

When I actually started doing the research and taking on the chartered [certified] teacher, and I started to realize—well I also realized that I knew a lot less than I thought I knew and there was a lot more to even learn, but that was part of that process. And at that point, you do start to grow—you don’t just grow in the profession, you start to grow as a person. Your confidence starts to develop, and that’s when it all starts to take off. (Poekert et al., 2016, p. 319)

Growth as a Leader

The leadership competency involves the “adoption of a leadership stance to advocate for self and others” (Poekert et al., 2016, p. 317). The word “stance” is intentional here as it refers to your perspective and the way you engage in your world. The leadership stance becomes a way of being with the recognition that everything you do and say will impact your students, colleagues, and the community. Leadership becomes who you are, not just a role you play. An American teacher noted,

I had the definition [of leader] in my mind … you’re going to be an administrator or you’re going to have a leadership role in the school, and then you’re a leader. Otherwise, you’re not … I wasn’t going to do any of those things … It’s amazing to me how my definition broadened, and I can see ways that I will impact other teachers … I need to do this. I have something I can share as a researcher, as a teacher. The confidence, for me[,] came from there. (Poekert et al., 2016, p. 320)

Personal Growth

Finally, personal growth is nested in the center of the model and is defined as “confidence in one’s ability to engage in continuous self-improvement” (Poekert et al., 2016, p. 317). This can be seen as part of a virtuous cycle. Each of the other three competencies contribute to teachers’ personal growth, and as they grow, the other competencies are also enhanced. One UK teacher noted:

I would see areas of weakness in the school, and you take it on yourself to develop initiative. You know, at the start, I wouldn’t have the confidence that my initiative was going to work, but now I would have that confidence, and it would make me more confident to take on a leadership role and to stay in my leadership role. (Poekert et al., 2016, p. 320)

This growth gave them the persistence and resilience to face challenges and take risks with confidence and courage.

The more you can sort of dare to change things within you and the way you teach and the way you personally grow in your teaching and teaching approaches, the more you dare to step into the other areas really. (Poekert et al., 2016, p. 321)

As you can see, this study validates the importance of changing the way we think about ourselves, our profession, and our schools. We can step up into the leadership stance and take the initiative to make changes where we see they are needed. We can apply systems and design thinking to investigate our particular system and to address problems with novel solutions.

What Teacher Leaders Say

During my years as a teacher, one of my favorite activities was to observe my class from ground level, sitting on the floor. From there I could get my students’ perspective of the classroom, and I could see places to improve that I otherwise would never have noticed. Similarly, we are best positioned to recognize problems in the systems where they touch our students’ lives. After all, promoting student learning is the primary aim of these systems. We spend more time with most of America’s children than their parents do (Wolk, 2008).

Jennifer Orr, elementary school teacher from Fairfax County, VA, and 2013 ASCD Emerging Leader (Teacher Collaborative and Education First, 2017), notes:

No one else in education comes to the table with the perspective teachers do. Teachers are doing the daily work of education. Every policy decision, every curriculum adopted, every new regulation, every change in boundaries, impacts that daily work. Teachers have a unique understanding of those impacts.

There are more than 3 million K–12 public school teachers. If you include early childhood educators and teachers working in independent schools, the number is around 4 million, an occupation with one of the largest workforces in the United States. Imagine the collective power teachers have to lead, especially if we teachers join forces with parents and school leaders. When teacher leaders form networks and teams to collaborate on addressing problems, amazing things begin to happen.

Today’s teachers are more than content deliverers. They are dreamers and thinkers who are envisioning students’ futures, not just their final semester grade. Veteran teachers possess a breadth of classroom knowledge with insight into changing student cultures and a pedagogical repertoire far more extensive than any teacher prep course could include in a syllabus. (Voiles, 2018, para. 3)

The National Network of State Teachers of the Year (NNSTOY) is building a cadre of teacher leaders. Derek Voiles, one such teacher, is the 2017 Tennessee Teacher of the Year and a member of NNSTOY. In an Education Week blog entitled “Want to Improve Schools? Look to Teacher Leaders,” Voiles shared his experience as a teacher leader empowered by the Teacher Leadership Network developed by the Tennessee Department of Education. This expansive program gives districts the resources to network and develop a plan for supporting teacher leadership. Voiles reports,

Once district plans are in place, Tennessee teachers can grow as leaders in many ways from district level leaders to statewide fellowships centered on various topics including policy and assessment. Teachers leverage their own specialty be it instructional strategies, data analysis, or technology use in the classroom. Many are given an extra period or extended contracts to provide coaching to their peers in these areas. (Voiles, 2018, para. 5)

Voiles is motivated to support his colleagues by his deep commitment to his students:

I want the best for all my students, which means I want them to experience the best education from the best teachers they can possibly have before, during, and after the time they are with me. The most important thing I can do to strengthen and improve their chances of success is to think beyond the doors of my classroom and be an active participant in the current move toward teacher leadership. (Voiles, 2018, para. 7)

In rural South Dakota, teacher leader Sharla Steever was concerned about the extremely high teacher turnover rate in her school district (Teach to Lead, 2020b). In some schools, all of the teachers would turn over from year to year, making it difficult to cultivate and maintain a supportive school climate and effective teaching. The schools in Steever’s district primarily serve the high-need populations of Native American reservation communities. New teachers were not prepared to navigate the complex problems their students were facing, such as community violence, high suicide rates, unemployment, and poverty. Steever wanted to address this problem, so she developed a team that built a mentoring support network for new teachers. They provided in-person and virtual mentoring, seasonal retreats for mentees and mentors to spend time together, and research-based approaches to becoming culturally responsive educators. Sharla noted, “Teacher leadership is about empowering teachers to address the concerns and needs they have … in a way that leads to transformation of those issues into solutions.” (Teach to Lead, 2020b, para. 4)

Systematic teacher leadership efforts are also developing in Louisiana where the state has adopted a policy to build a sustainable teacher leadership infrastructure. Since 2013 the state has been cultivating thousands of teacher leaders. They created a teacher leader certification process that involves a series of curriculum specific trainings.

Teachers are even addressing the issue of teacher leadership itself. Mississippi consistently ranks at the bottom of educational rankings for student outcomes and teacher quality. Mary Margarett King, Mississippi State Teacher of the Year wanted to develop a state chapter of NNSTOY to develop teacher leaders to advocate for much needed education reforms (Teach to Lead, 2020a). “As teacher leaders, we have a responsibility to empower teachers, to advance the profession, and to impact students,” Mary Margarett said. “Teacher leadership is empowering!” (Teach to Lead, 2020a, para. 5).