Appendix B

The Bandit Tradition

I

As every movie-goer and television-watcher knows, bandits, whatever their nature, tend to exist surrounded by clouds of myth and fiction. How do we discover the truth about them? How do we trace their myths?

Most of the bandits around whom such myths have formed are long dead: Robin Hood (if there was one) lived in the thirteenth century, though in Europe heroes based on figures from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries are the most common, probably because the invention of printing made possible the main medium for the survival of ancient bandit memories, the cheap popular broadsheet or chapbook. Passing from one set of storytellers, from one place and public to another throughout the generations, such a mode of transmission can tell us very little of documentary value about the bandits themselves, except that, for whatever reason, their subjects are remembered. Unless they have left traces in the records of the law and the authorities who pursued them, we have hardly any direct contemporary evidence about them. Foreign travellers captured by bandits, notably in South-East Europe, have left such reports from the nineteenth century; journalists, anxious to interview more than willing young men in bandoleers, not before the twentieth. Nor can even their reports always be taken at face value, if only because outside witnesses rarely knew very much about the local situation, even if they could understand, let alone speak the sometimes impenetrable local patois, and resisted the demands of sensation-hungry news editors. At the time this is being written, kidnapping foreigners – for ransom or in order to bargain for concessions from the government – has become fashionable in the Arabian republic of Yemen. So far as I can judge, little relevant information has been extracted from liberated prisoners.

Tradition, of course, shapes our knowledge of even those twentieth-century social bandits – and there are several – about whom we have reliable first-hand knowledge. Both they and those who reported their ventures are familiar from childhood with the part of the ‘good bandit’ in the drama of poor countrymen’s lives, and cast themselves or him for it. M. L. Guzman’s Memorias de Pancho Villa are not only based in part on Villa’s own words, but are the work of a man who was both a great Mexican literary figure and (in the judgement of Villa’s biographer) ‘an extremely serious scholar as well’.1 Yet in Guzman’s pages Villa’s early career conforms a good deal more to the Robin Hood stereotype than it seems to have done in real life. This is even more so in the case of the Sicilian bandit Giuliano, who lived and died in the high noon of press photographers and celebrity interviews in exotic places. But he knew what was expected of him (‘How could a Giuliano, loving the poor and hating the rich, ever turn against the masses of the workers?’ he asked, having just massacred several of them), and so did journalists and novelists. Even his enemies, the Communists, correctly predicting his end, regretted that it was ‘unworthy of an authentic son of the labouring people of Sicily’, ‘loved by the people and surrounded by sympathy, admiration, respect and fear’.2 His contemporary reputation was such that, as an old militant of the region told me, after the 1947 massacre at the Portella della Ginestra nobody had supposed that it could possibly have been the work of Giuliano.

Convenient and old-established myths are also available for bandits such as avengers and haiduks whose reputation cannot dwell on social redistribution and sympathy for the poor, at least so long they are not simple agents of official law or government. (Many an otherwise hateful rural tough has acquired a public halo merely by being the enemy of army or police.) It is the stereotype of the warrior’s honour, or, in Hollywood terms, of the cowboy hero. (Since, as we have seen, so many bandits came from specialized martial communities of pastoral raiders, whose military capacities were recognized by rulers, nothing was more familiar to their young men.) Honour and shame, as the anthropologists tell us, dominated the value-system in the Mediterranean, the classic region of Western bandit myth. Where available, feudal values reinforced it. Heroic robbers were, or regarded themselves as, ‘noble’, a status which – at least in theory – also implied moral standards worthy of respect and admiration. The association has survived into our distinctly non-aristocratic societies (as in ‘gentlemanly behaviour’ or ‘a noble gesture’ or noblesse oblige). ‘Nobility’ in this sense links the most brutal of the hard men with guns to the most idealized of Robin Hoods, who are indeed classified as ‘noble robbers’ (‘edel Räuber’) in several countries for this reason. The fact that a number of bandit chieftains celebrated in myth may actually have come from armigerous families (even if the term Raubritter – robber baron – does not appear in literature before the nineteenth-century liberal historians) strengthened the linkage.

Thus the first major entrance of the noble bandit into high culture (i.e. into the literature of the Golden Century of Spain) stresses both their supposed social status as gentlemen, i.e. their ‘honour’, as well as their generosity, not to mention (as in Lope de Vega’s Antonio Roca, based on a Catalan brigand of the 1540s) the good sense of moderation in violence and not antagonizing the peasantry. The French memorialist Brantôme (1540–1614), echoing at least one contemporary judgement, described him in his Vie des dames galantes as ‘one of the bravest, most valiant, shrewd, wary, capable and courteous bandits ever seen in Spain’. In Cervantes’ Don Quixote, the bandit Rocaguinarda (active in the early seventeenth century) is even presented as specifically on the side of the weak and poor.3 (Both were in fact of peasant origin.) The actual record of what has been called ‘the Catalan Baroque bandits’ is far from that of Robin Hoods. Does the ability of the great Spanish writers to produce a mythological version of noble banditry at the very time when the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century epidemic of real banditry was at its peak prove their remoteness from reality or simply the enormous social and psychological potential of the existence of the brigand as an ideal type? The question must be left open. In any case the suggestion that Cervantes, Lope, Tirso de Molina and the other glories of Castilian high culture are responsible for the later positive image of banditry in popular tradition, is implausible. Literature had no need to give robbers a potential social dimension.

The most perceptive history of the original Robin Hood’s tradition has recognized this even among robbers who laid no claim to it.4 It stresses ‘the difficulty of defining crime, especially by the haziness of the borderline between crime and politics, and by the violence of political life’ in fourteenth-and fifteenth-century England. ‘Crime, local rivalries, the control of local government, the bringing to bear of the authority of the crown, all intermingled. This made it easier to imagine that the criminal had some right on his side. He gained social approval.’ As in the value-system of Hollywood Westerns, rough-and-ready justice, the violent redress of wrong (known as ‘Folville’s Law’, after a knightly family famous for righting its own wrongs in this way) was a good thing. The poet William Langland (whose Piers Plowman – c. 1377 – incidentally contains the first reference to Robin Hood ballads) thought that Grace endowed men with the qualities to fight Antichrist, including

Some to ride and recover what was wrongfully taken.

He showed them how to regain it through the might of their hands

And wrest it from false men by Folville’s laws. (Prof. Holt’s translation)

Contemporary public opinion, even outside the outlaw’s own community, was therefore prepared to focus on socially commendable aspects of a celebrated bandit’s activities, unless, of course, his reputation as an anti-social criminal was so shocking as to make him an enemy to all honest folk. (In that case tradition provided an alternative, which nevertheless satisfied the public’s appetite for highly-coloured drama in the form of no-holds-barred chapbook confessions by notorious malefactors which detailed their progress from an initial breach of the Ten Commandments through a horrifying criminal career, to a plea for divine and human forgiveness at the foot of the gallows.)

Naturally, the more remote the public was – in time or space – from a celebrated brigand, the easier it was to concentrate on his positive aspects, the easier to overlook the negative. Nevertheless the process of selective idealization can be traced back to the first generation. In societies with a bandit tradition, if, among other targets, a brigand attacked those of whom public opinion disapproved, he immediately acquired the entire Robin Hood legend – including impenetrable disguises, invulnerability, capture by treason and the rest (see Chapter 4). Thus Sergeant José Avalos, retired from the gendarmerie to farm in the Argentine Chaco, where he had himself in the 1930s pursued the celebrated bandit Maté Cosido (Segundo David Peralta, 1897–?), had no doubt at all that he had been a ‘people’s bandit’. He had never robbed good Argentines, but only the agents of the big international farm-produce corporations, ‘los cobradores de la Bunge y de la Clayton’. (‘Of course’, as he put it to me when I interviewed the old frontiersman on his farm in the late 1960s, ‘my trade [oficio] was to catch him, just as it was his trade [oficio] to be a bandit.)’ I was therefore able to predict successfully what he would claim to remember about him.* It is indeed true that the famous bandit had held up the car of a representative of Bunge & Born, relieving him of 6,000 pesos in 1935; he had also held up a train which carried, among the other victims, presumably ‘good Argentines’, a man from Anderson, Clayton & Co. (12,000 pesos), and netted as much as 45,000 in a raid on a local office of Dreyfus – still, with Bunge, one of the biggest names in the global farm-produce trade – both in 1936. However, the record shows that the band’s specialities, train-robbery and kidnapping for ransom, showed no patriotic discrimination.5 It was the public that remembered the foreign exploiters and forgot the rest.

The situation was even clearer in feuding societies, where a ‘legitimate’ homicide was criminalized by the state; all the more so when hardly anybody believed in the impartiality of the state’s justice. Giuseppe Musolino, a lone outlaw, from start to finish utterly refused to accept that he was a criminal in any sense, and indeed in jail refused to wear the criminal prisoner’s uniform. He was neither bandit nor brigand, he had neither robbed nor stolen, but merely killed spies, informers and infami. Hence at least some of the extraordinary sympathy, almost veneration, and protection he enjoyed in the countryside of his region of Calabria. He believed in the old ways against the evil new ways. He was like the people: living in bad times, unjustly treated, weak, victimized. He was unlike them only in standing up against the system. Who cared about the details of the local political conflicts which had led to the original homicide?6

In a politically polarized situation, such selection was even easier. Thus a classic Carpathian bandit legend has developed in the Beskid Mountains of Poland around one Jan Salapatek (‘The Eagle’), 1923–55, a resistance fighter in the Polish Home Army during the war, who continued in the anti-Communist resistance after the war, and who appears to have remained an outlaw in the inaccessible highland forests until killed by the agents of the Cracow Security Service.7 Whatever the reality of his career, given the distrust of the peasants for new regimes, his myth is indistinguishable from the traditional legend of the good bandit – ‘there are only some superficial changes in it: an axe is replaced by an automatic gun, a landlord’s palace by communist cooperative store and ‘‘starosta’’ by Stalinist Security Service’. The good bandit wronged nobody. He stole from co-operatives but never people. The good bandit always exists in contradistinction to the bad robber. So, unlike some, including even some anti-Communist partisans, Salapatek wronged nobody (‘I remember there was partisan from the same village – he was son of bitch’ [sic]). He was the man who helped poor people. He distributed sweets in the school yard, went to the bank, brought money, ‘threw it on the square and said ‘‘take it, that’s your money which does not belong to the state’’ ’. In proper legendary fashion, though oddly for a guerrilla fighter against the regime, he used violence only in self-defence and never initiated shooting. In short, ‘he was really just and wise, he was honestly fighting for Poland’. It may or may not be relevant that Salapatek was born in the same village as Pope John Paul II.

Indeed, since everyone in countries with a developed bandit tradition expected to see someone in the role of the noble bandit, including policemen, judges and brigands themselves, it was possible for a man to become a Robin Hood in his own lifetime, if he met the minimum requirements of the part. This was plainly the case with Jaime Alfonso ‘El Barbudo’ (1783–1824), as attested by reports in the Correo Murciano in 1821 and 1822 and in Lord Carnarvon’s (1822) voyage through the Iberian Peninsula.8 It was clearly also the case with Mamed Casanova, who flourished in Galicia in the early 1900s. He was described (and photographed) as ‘el Musolino Gallego’ by a Madrid journal (for Musolino, see also pp. 46, 55), as ‘bandit and martyr’ in the Diario de Pontevedra, and defended by a lawyer who subsequently became President of the Real Academia Gallega. He reminded the court in 1902 that ballads by folk-poets and romances sold on city streets attested to the popularity of his celebrated client.9

I I

Some brigands can therefore acquire the legend of the good bandit in their own lifetime, or certainly in the lifetime of their contemporaries. Moreover, contrary to some sceptics, even famous bandits whose original reputation is unpolitical may soon acquire the useful attribute of being on the side of the poor. Robin Hood, whose social and political radicalism does not fully emerge until the 1795 collection of the Jacobin Joseph Ritson,10 has social objectives even in the first, fifteenth-century version of his story: ‘For he was a gode outlawe, And dyd pore men moch god.’ Nevertheless, in its written form at least, in Europe the fully developed social bandit myth only appears in the nineteenth century, when even the least suitable candidates were apt to be idealized into champions of national or social struggle, or – under the inspiration of Romanticism – into men unconfined by the constraints of middle-class respectability. The vastly successful genre of German bandit novels of the early nineteenth century, has been summarized as: ‘plots full of action . . . provided the middle-class reader with descriptions of violence and sexual freedom . . . While crime has stereotypical roots in parental neglect, defective education and seduction by loose women, the ideal middle-class family, tidy, orderly, patriarchal and passions-reducing, is presented both as the ideal and the foundation of an ordered society.’11 In China, of course, the myth is age-old: the first legendary bandits date back to the period of the ‘warring states’, 481–221 bc, and the great bandit classic, the sixteenth-century Shuihu Zhuan, based on a real band of the twelfth century, was as familiar to illiterate villagers from storytellers and itinerant drama troupes as it was to every educated young Chinese, not least Mao.12

Nineteenth-century Romanticism has certainly helped to shape the subsequent taste for the bandit as an image of national, social, or even personal liberation. I cannot deny that in some ways my view of ‘haiduks’ as ‘a permanent and conscious focus of peasant insurrection’ (see above, p. 78) was influenced by it. Nevertheless, the set of beliefs about social banditry is simply too strong and uniform to be reduced to an innovation of the nineteenth century or even a product of literary construction. Where the popular rural, and even city, public had a choice, it selected those parts of bandit literature or bandit reputation that fitted the social image. Roger Chartier’s analysis of the literature on the bandit Guilleri (active in Poitou 1602–8) demonstrates that, given the choice between an essentially cruel gangster redeemed only by bravery and final contrition, and a man of good qualities who, though a bandit, was far less cruel and brutal than soldiers and princes, readers preferred the second. This was the basis of what from 1632 on became the first literary portrait in French of the classic and mythically stereotyped ‘good bandit’ (‘le brigand au grand coeur’), qualified only by the requirement of state and church that criminals and sinners must not be allowed to get away with it.13

The process of selection is even clearer in a bandit without significant literary memorials, investigated both in the archives and by interviews with 135 aged informants in 1978–9.14 The folk memory that survives about Nazzareno Guglielmi, ‘Cinicchio’, (1830–?) in the area of Umbria around his native Assisi, is the classic ‘noble robber’ myth. Although ‘the figure of Cinicchio which emerges from archival research is not substantially in conflict with the oral tradition’, in real life he was plainly not an ideal-typical Robin Hood. Yet while he made political alliances, and anticipated the later Mafioso methods by offering, for regular payments, to protect landowners against other bandits (not to mention himself ), the oral tradition insists on his refusal to make deals with the rich and especially on his campaign of hatred and – significantly – revenge against Count Cesare Fiumi, who, it claims, had unjustly accused him. However, in this case there is also a more modern element in the myth. The bandit, who disappears from sight in the 1860s after organizing an escape to America, is supposed to have become very prosperous there, and at least one of his sons is said to have become a successful engineer. In late twentieth-century rural Italy, social mobility is also the reward of being a noble robber . . .

I I I

Which bandits are remembered? The number of those who survived the centuries in popular song and story is actually quite modest. Only about thirty songs about the banditry of sixteenth and seventeenth-century Catalonia were found by the folklore collectors of the nineteenth century and only about six of these are exclusively about particular bandits. (A third of the total are songs about the early seventeenth-century Unions against the attacks of bandits.) Not more than half-a-dozen Andalusian bandits became really famous. Only two Brazilian cangaçeiro chieftains – Antonio Silvino and Lampião – have made it into the national memory. Of nineteenth-century Valencian-Murcian bandits, only one acquired the myth.15 Much, of course, may have been lost because of the impermanence of chapbooks and ballad sheets and the hostility of authorities, which sometimes penalized such material. Even more may never have reached print, or escaped the explorations of the earlier folklorists. A work published in 1947 mentions two examples of the religious cults around the graves of some dead brigands in Argentina (see p. 55 above); a later inquiry discovered at least eight. With one exception, none had attracted the attention of the educated public.16

Nevertheless, there is clearly some process that selects some bands and their leaders for national, or even international, fame while leaving others to local antiquarians or obscurity. Whatever it is that initially singles them out, the medium of their fame until the twentieth century was print. Since all the films about famous bandits known to me are based on figures first established by ballad, chapbook and newspaper reports, it may even be argued that this is still the case today, in spite of the retreat of the printed word (outside the computer screen) before the moving image of film, television and video. However, the memory of bandits has also been preserved by their association with particular places, such as Robin Hood’s Sherwood Forest and Nottingham (locations dismissed by historical research), the Mount Liang of the Chinese bandit epic (in Shandong province) and several anonymous ‘robber’s caves’ on Welsh, and doubtless other, mountainsides. The special case of shrines devoted to the cults of dead bandits has been considered above.

Yet tracing the traditions by which particular bandits have been chosen for fame and survival is less interesting than tracing the changes in the collective tradition of banditry. Here there is a considerable difference between the places where banditry, if it ever occurred on any significant scale, is beyond living memory, and those where it is not. This is what distinguishes Britain, or the last three centuries in the Midi of France (‘where we have no record of large bands’17) from countries like Chechnya, where it is very much alive today, and those in Latin America, where it is within the memory of men and women who are still alive. Somewhere between these are the countries where the memory of nineteenth-century banditry or its equivalent is kept alive, partly by national tradition but mostly by the modern mass media, so that it can still act as a model of personal style, like the Wild West in the USA, or even of political action, like the Argentine guerrillas of the 1970s who saw themselves as the successors of the montoneros whose name they adopted, a choice which, their historian holds, enormously increased their appeal to potential recruits and the public.18 In countries of the first kind, the memory of real bandits is dead, or has been overlaid by other models of social protest. What survives is assimilated to the standard bandit myth. This has already been discussed at length.

Much the most interesting are the countries of the second kind. So it may be useful to conclude this chapter with some reflections on three of them, where the very different itinerary of the national bandit tradition can be compared: Mexico, Brazil and Colombia.19 All three are countries which became familiar with large-scale banditry in the course of their history.

All travellers along its roads agreed that, if any Latin American state was quintessentially bandit country, it was nineteenth-century Mexico. Moreover, in the first sixty years of independence the breakdown of government and economy, war and civil war gave any body of armed men which lived by the gun considerable leverage, or at least the choice between joining army or police force on government pay (which, then as later, did not exclude extortion) or sticking to simple brigandage. Benito Juarez’s Liberals, in their civil wars, lacking more traditional patronage, used them extensively. However, the bandits around whom the popular myths formed were those of the stable era of Porfirio Diaz’s dictatorship (1884–1911) which preceded the Mexican Revolution. These bandits could be seen, even at the time, as challengers of authority and the established order. Later, with sympathetic hindsight, they might appear as precursors of the Mexican Revolution.20 Thanks chiefly to Pancho Villa, the most eminent of all brigands turned revolutionaries, this has brought banditry a unique degree of national legitimacy in Mexico, though not in the USA, where in those very years violent, cruel and greedy Mexican bandits became the standard villains of Hollywood, at least until 1922 when the Mexican government threatened to ban all films made by offending movie companies from the country.21 Of the other bandits who became nationally famous in their lifetime – Jesus Arriaga (Chucho El Roto) in central Mexico, Heraclio Bernal in Sinaloa, and Santana Rodriguez Palafox (Santanon) in Veracruz – at least the first two still enjoy popularity. Bernal, killed in 1889, who was in and out of politics, is probably the most famous in the age of the media, celebrated in thirteen songs, four poems, and four movies, some adapted for television, but I suspect that the impudent Catholic but anti-clerical trickster Chucho (died 1885), who has also made it on to the TV screens, remains closer to the heart of the people.

RUSSIA AND EASTERN EUROPE

The haiduk revolutionary: Panayot Hitov (1830–1918), Bulgarian outlaw, patriot and autobiographer, leader of the national rising of 1867-8.

The Klephtic image: Giorgios Volanis (center), leader of Greek bands in Macedonia in the Early 1900s. Note the warrior’s ornaments.

Balkan irregulars: Constantine Garefis, with his band (recruited around Olympus), c.1905. He was Killed by his enemies the Macedonian Komitadjis in 1906.

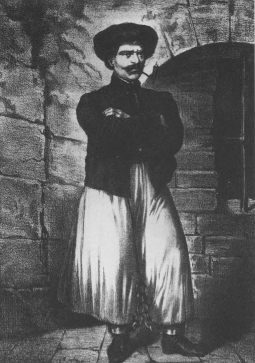

The bandit of the plains. Sandor Rósza (1813–78), the great Hungarian brigand-guerilla, in jail. A band-leader from c. 1841, a national guerilla after 1849, he was captured in 1856 and pardoned in 1867.

Sandor Rósza as legend: a scene from Miklos Jancso’s film The Round-up, which deals with the Pursit of Rósza by the imperal authorities.

ASIA

Wu Sung, commander of an infantry of a bandit army in the famous Water Margin Novel, in a sixteenth-century illustration. He became an outlaw through a vengeance killing. He was described as ‘tall, handsome, powerful, heroic, expert in military arts’, and drink.

Chieh Chen, a rank-and-file bandit from the Water Margin Novel, which was composed in the thirteenth century, probably based on earlier themes. He came from Shantung, an orphan, a hunter, and was described as tall, tanned, slim and hot-tempered.

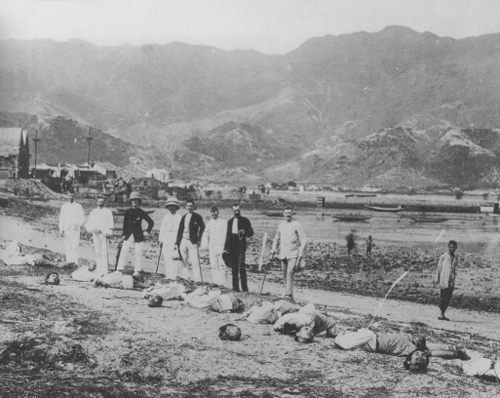

Execution of Namoa Pirates, Kowloon 1891, with British sahibs. Namoa, an island ofFSwatow, was a great centre for piracy and, at this time, the scene of a rebellion. We do not know whether the corpses had been pirates, rebels or both.

The Pindaris, described as ‘a well-known professional class of freebooters’, were associated with the Marathas in whose campaigns they took part, looting. After the British pacification the remainder settled down as cultivators.

THE EXPROPRIATIONS

‘Kamo’ (Semyon Arshakovich Ter-Petrossian), 1882–1922. A Bolshevik professional revolutionary from Armenia, he was noted as an immensely tough and courageous man of action. He was the instigator of the Tiflos hold-up of 1907.

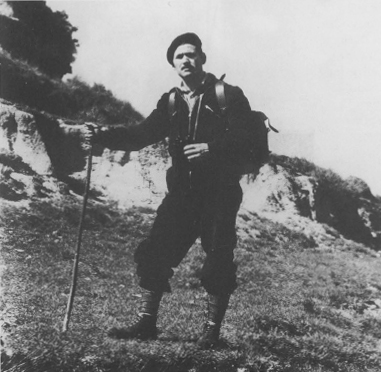

Francisco Sabaté (‘El Quico’), 1913–60, Catalan anarchist and expropriator. The photo was taken in 1957 and shows him in frontier-crossing equipment.

THE BANDIT IN ART

The monumental bandit: Head of Brigands by Salvator Rosa (1615–73).

The statuesque bandit: Captain of Banditti by Salvator Rosa, in an English eighteenth-century engraving.

The savage bandit: Francisco Goya y Lucientes (1746–1848). One of several studies on this theme by Goya.

The sentimental bandit: Bandit of the Apennines (1824), by Sir Charles Eastlake (1793–1865), President of the Royal Academy.

The bandit as symbol: Ned Kelly (1956) by Sidney Nolan. Part of a series about the famous bushranger (1854–80) with his home-made armour.

Unlike Mexico, Brazil moved from colony to independent empire without disruption. It was the First Republic (1889–1930) which produced, at least in the grim hinterlands of the north-east, the social and political conditions for epidemic banditry: that is to say, transformed the groups of armed retainers tied to particular territories and elite families into independent operators roaming over the area of perhaps 100,000 square kilometres covering four or five states. The great cangaçeiros of the period 1890–1940 soon became regionally famous, their reputation spread orally and in chapbooks, which appear in Brazil not earlier than 1900,22 by local poets and singers. Mass migration to the cities of the south and growing literacy were later to spread this literature to the shops and market stalls of the monster cities like São Paulo. The modern media brought the cangaçeiros, an obvious local equivalent to the Wild West, on to cinema and television screens, all the more readily as the most famous of them, Lampião, was actually the first great bandit to be filmed live in the field.* Of the two most celebrated bandits, Silvino acquired a ‘noble robber’ myth in his lifetime, which was reinforced by journalists and others to contrast with the great but hardly benevolent reputation of Lampião, his successor as the ‘king of the backlands’.

Yet it is the political and intellectual co-option of the cangaçeiros into Brazilian national tradition that is interesting. They were very soon romanticized by north-eastern writers, and, in any case, were easy to turn into demonstrations of the corruption and injustice of political authority. Insofar as Lampião was a potential factor in national politics, they attracted wider attention. The Communist International even thought of him as a possible revolutionary guerrilla leader, perhaps suggested by the leader of the Brazilian Communist Party, Luis Carlos Prestes, who in his earlier career as leader of the ‘Long March’ of military rebels came into contact with Lampião (see pp. 100–101). However, the bandits do not seem to have played a major part in the important attempt by the Brazilian intellectuals of the 1930s to build a concept of Brazil with popular and social as against elite and political bricks. It was in the 1960s and 1970s that a new generation of intellectuals transformed the cangaçeiro into a symbol of Brazilianness, of the fight for freedom and the power of the oppressed; in short, as ‘a national symbol of resistance and even revolution’.23 This in turn affects the way he is presented in the mass media, even though the popular chapbook/oral tradition was still alive among north-easterners, at least in the 1970s.

The Colombian tradition has followed a very different trajectory. It is, for obvious reasons, completely overshadowed by the bloodthirsty experience of the era after 1948 (or, as some historians prefer, 1946) known as La Violencia and its aftermath. This was essentially a conflict combining class warfare, regionalism and political partisanship of rural populations identifying themselves, as in the republics of the River Plate, with one or other of the country’s traditional parties, in this case the Liberals and Conservatives, which turned into guerrilla war in several regions after 1948, and eventually (apart from the regions where the now powerful Communist guerrilla movement developed in the 1960s) into a congeries of defeated, formerly political armed bands, relying on local alliances with men of power and peasant sympathy, both of which they eventually lost. They were wiped out in the 1960s. The memory they have left has been well described by the best experts on the subject:

Perhaps, except for the idealized memory that the peasants still hold in their old zones of support, the ‘social bandit’ has also been defeated as a mythical character . . . What took place in Colombia was the opposite process from that of the Brazilian cangaço. Over time the cangaço lost much of its characteristic ambiguity and developed towards the image of the ideal social bandit. The cangaçeiro ended up as a national symbol of native virtues and the embodiment of national independence . . . In Colombia, on the contrary, the bandit personifies a cruel and inhuman monster or, in the best of cases, the ‘son of the Violencia’, frustrated, disoriented and manipulated by local leaders. This has been the image accepted by public opinion.24

Whatever the images of the FARC (Fuerzas Armadas de la Revolución Colombiana – the chief guerrilla force in Colombia since 1964) guerrillas, paramilitaries and drug-cartel gunmen that will survive into the twenty-first century, they will no longer have anything in common with the old bandit myth.

What, finally, of the oldest and most permanent tradition of social banditry, that of China? Egalitarian or at least at odds with the strictly hierarchical ideal of Confucius, representing a certain moral ideal (carrying out ‘the Way on Heaven’s behalf’), it survived two millennia. What of the bandit rebels like Bai Lang (1873–1915) about whom they sang:

Bai Lang, Bai Lang –

He robs the rich to aid the poor,

And carries out the Way on Heaven’s behalf.

Everyone agrees that Bai Lang’s fine:

In two years rich and poor will all be levelled.25

It is hard to imagine that the decades of the warlord and bandit pandemic that followed the end of the Chinese Empire in 1911 will be remembered with much affection by anyone who experienced them. Nevertheless, though the scope for banditry declined dramatically after 1949, one would suspect that the bandit tradition survived well enough in the traditional ‘bandit regions’ of the still essentially rural China of the first decades of communism, in spite of Party hostility. We may suppose that it will migrate into the new giant cities which suck in poor country people in their millions in China as in Brazil. Moreover the great literary monuments to the bandit life, like the Shuihu Zhuan, will certainly continue as part of educated Chinese culture. Perhaps they will find a future, both popular and highbrow, on twenty-first-century Chinese screens, like that discovered for the not entirely dissimilar samurai roving sword-fighters and knights errant on those of twentieth-century Japan. One suspects that their potential as romantic myths is far from exhausted.