8

Bandits and Revolutions

Flagellum Dei et commissarius missus a Deo contra usurarios et detinentes pecunias otiosas. (Scourge of God and envoy of God against usurers and the possessors of unproductive wealth.)

Self-description by Marco Sciarra, Neapolitan brigand chief of the 1590s.1

At this point the bandit has to choose between becoming a criminal or a revolutionary. As we have seen, social banditry by its nature challenges the established order of class society and political role in principle, whatever its accommodations with both in practice. Insofar as it is a phenomenon of social protest, it can be seen as a precursor or potential incubator of revolt.

In this it differs sharply from the ordinary underworld of crime, with which we have already had occasion to contrast it. The underworld (as its name implies) is an anti-society, which exists by reversing the values of the ‘straight’ world – it is, in its own phrase, ‘bent’ – but is otherwise parasitic on it. A revolutionary world is also a ‘straight’ world, except perhaps at especially apocalyptic moments when even the anti-social criminals have their access of patriotism or revolutionary exaltation. Hence, for the genuine underworld, revolutions are little more than unusually good occasions for crime. There is no evidence that the flourishing underworld of Paris provided revolutionary militants or sympathizers in the French revolutions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, though in 1871 the prostitutes were strongly Communard; but as a class they were victims of exploitation rather than criminals. The criminal bandit gangs which infested the French and Rhineland countryside in the 1790s were not revolutionary phenomena, but symptoms of social disorder. The underworld enters the history of revolutions only insofar as the classes dangereuses are mixed up with the classes laborieuses, mainly in certain quarters of the cities, and because rebels and insurgents are often treated by the authorities as criminals and outlaws, but in principle the distinction is clear.

SPAIN AND ITALY

Giuseppe Musolino. Born in 1875 in San Stefano, Aspromonte, he was wrongly imprisoned in 1897, escaped in 1899, and was recaptured in 1901. He was in jail for forty-five years, where he went mad, and died in 1956. He was immensely popular and famous far beyond his native Calabria.

Bandit territory: the Barbagia in Sardinia. From De Seta’s film Banditti ad Orgosolo (1961), which reconstructs the making of a bandit from this legendary centre for outlaws.

The brigand romanticised by Charles-Alphonse-Paul Bellay (1826—1900), a copious exhibitor at the Paris Salon, with a penchant for picturesque Italian popular types.

Salvatore Giuliano (1922—50) alive. The most celebrated bandit of the Italian republic was much, and flatteringly photographed by journalists.

Salvatore Giuliano dead, 5 July 1950, in a courtyard at Castlevetrano. The police, improbably, claimed credit for the killing. Note the pistol and the Brer) gun.

Salvatore Giuliano. An ambush by the gang reconstructed in Francesco de Rosi’s magnificent film. The locations are actual.

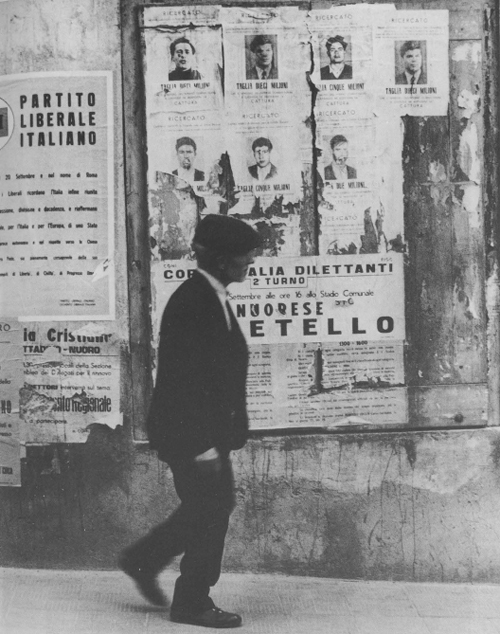

Sardinia in the 1960s. Posters of bandits wanted by the police, with rewards ranging from two to ten million lire a head. Banditry is still endemic in the Barbagia highlands.

THE AMERICAS

The James Boys as heroes of popular fiction (Chicago, 1892). Perhaps their habit of holding up trains helped to spread their fame.

Jesse James (1847-82), with his brother Frank (1843-1915) the most famous actor of the social bandit role in US history. He was born and died in Missouri. He formed his band after the Civil War (1866).

Jesse James as part of the Western Legend. Henry Fonda in the film Jesse James (1939, Henry

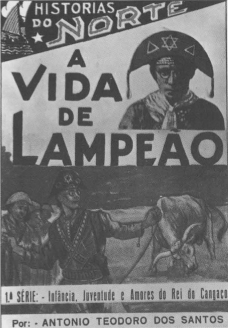

Lampião (?i898—1938), the great bandit-hero of Brazil. Title-page of part 1 of a three-part verse romance by a North-eastern balladeer, published in the giant industrial city of São Paulo (1962).

The bandit as national myth, propagated by intellectuals: a still from the Brazilian film O Cangaçeiro (1953). The decorated leather hats with upturned brim are the local equivalent of the sombrero or stetson.

Pancho Villa (born in 1877 in Durango, died in 1923 in Chihuahua). The famous brigand as revolutionary general, December 1913.

Bandits, on the other hand, share the values and aspirations of the peasant world, and as outlaws and rebels are usually sensitive to its revolutionary surges. As men who have already won their freedom they may normally be contemptuous of the inert and passive mass, but in epochs of revolution this passivity disappears. Large numbers of peasants become bandits. In the Ukrainian risings of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries they would declare themselves Cossacks. In 1860–1 the peasant guerrilla units were formed around, and like, brigand bands: local leaders would find themselves attracting a massive influx of disbanded Bourbon soldiers, deserters, or evaders of military service, escaped prisoners, men who feared persecution for acts of social protest during Garibaldi’s liberation, peasants and mountain men seeking freedom, vengeance, loot, or a combination of all these. Like the usual outlaw band, these units would initially tend to form in the neighbourhood of the settlements from which they drew their recruits, establish a base in the nearby mountains or forests, and begin their operations by activities hard to distinguish from those of ordinary bandits. Only the social setting was now different. The minority of the unsubmissive were now joined in mobilization by the majority. In short, to quote a Dutch student of Indonesia, at such times ‘the robber band associates itself with other groups and expresses itself under that guise, whilst the groups which originated with more honest ideals take on the character of bandits’.2

An Austrian official in the Turkish service has given an excellent description of the early stages of such a peasant mobilization in Bosnia. At first it only looked like an unusually stubborn dispute about tithes. Then the Christian peasants of Lukovac and other villages gathered, left their houses and went on to the mountain of the Trusina Planina, while those of Gabela and Ravno stopped work and held meetings. While negotiations went on, a band of armed Christians attacked a caravan from Mostar near Nevesinye, killing seven Moslem carters. The Turks thereupon broke off talks. At this point the peasants of Nevesinye all took arms, went on to the mountain and lit alarm-fires. Those of Ravno and Gabela also took arms. It was evident that a major uprising was about to break out – in fact the rising which was to initiate the Balkan wars of the 1870s, to detach Bosnia and Herzegovina from the Ottoman Empire, and to have a variety of important international consequences, which do not concern us here.3 What does concern us is the characteristic combination of mass mobilization and expanded bandit activity in such a peasant revolution.

Where there is a strong haiduk tradition or powerful independent communities of armed outlaws, free and armed peasant raiders, banditry may impose an even more distinct pattern on such revolts, since it may have already been recognized, in a vague sense, as the relic of ancient or the nucleus of future freedom. Thus in Saharanpur (Uttar Pradesh, India), the Gujars, an important minority of the population, had a strong tradition of independence or ‘turbulence’ and ‘lawlessness’ (to use the phraseology of the British officials). The great Landhaura estate of the Gujars was broken up in 1813. Eleven years later, when times in the countryside were hard, ‘the bolder spirits’ in Saharanpur ‘sooner than starve, banded themselves together under a brigand chief named Kallua’, a local Gujar, and engaged in banditry on either side of the Ganges, robbing banias (the trading and moneylending caste), travellers and inhabitants of Dehra Dun. ‘The motives of the dacoits’, observes the Gazetteer, ‘were perhaps not so much mere plunder as the desire of the return to the old lawless way of living, unencumbered by the regulations of superior authority. In short, the presence of armed bands implied rebellion rather than mere law-breaking.’4

Kallua, allying with an important taluqdar* who controlled forty villages and other disgruntled gentry, soon extended his revolt by attacking police posts, capturing some treasure from two hundred police guards and sacking the town of Bhagwanpur. Thereupon he declared himself to be the Raja Kalyan Singh and dispatched messengers in royal fashion to exact tribute. He now had a thousand men, and announced that he would overthrow the foreign yoke. He was defeated by a force of two hundred Gurkhas, having had ‘the incredible presumption to await the attack outside the fort’. The rebellion lasted into the next year (‘another hard season . . . had given them an accession of new recruits’), and then petered out.

The bandit chief who is regarded as a royal pretender or seeks to legitimize revolution by adopting the formal status of a ruler, is familiar enough. The most formidable examples are perhaps the bandit and Cossack chieftains of Russia, where the great rasboiniki always tended to be regarded as miraculous heroes, akin to the champions of the Holy Russian land against the Tatars, if not actually as possible avatars of the ‘beggars’ Tsar’ – the good Tsar who knew the people and would replace the evil Tsar of the boyars* and the gentry. The great peasant rebels of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries along the lower Volga were Cossacks – Bulavin, Bolotnikov, Stenka Razin (the hero of folk-song) and Yemelyan Pugachov – and Cossacks were in those days communities of free peasant raiders. Like Raja Kalyan Singh, we find them issuing imperial proclamations; like the brigands of southern Italy in the 1860s we find their men killing, burning, pillaging, destroying the written documents which signify serfdom and subjection, but lacking any programme except that of sweeping away the machinery of oppression.

For banditry itself thus to become the revolutionary movement and to dominate it, is unusual. As we have seen (above, pp. 28–30), limitations, both technical and ideological, are such as to make it unsuitable for more than momentary operations of more than a few dozen men, and its internal organization provides no model which can be generalized to be that of an entire society. Even the Cossacks, who developed quite large and structured permanent communities of their own, and very substantial mobilizations for their raiding campaigns, provided only leaders and not models for the great peasant insurrections: it was as ‘people’s Tsars’ and not as atamans† that they mobilized these. Banditry is therefore more likely to come into peasant revolutions as one aspect of a multiple mobilization, and knowing itself to be a subordinate aspect, except in one sense: it provides fighting men and fighting leaders. Before the revolution it may be, to use the phrase of an able historian of Indonesian peasant unrest, ‘a crucible out of which emerged a religious revival on one hand, and revolt on the other’.5 As the revolution breaks out, they may merge with the vast millennial outburst: ‘Rampok bands sprang from the ground like mushrooms, speedily followed by roving groups of the populace, possessed with the expectation of a Mahdi or a millennium.’ (This is a description of the Javanese movement after the defeat of the Japanese in 1945.)6 Yet without the expected Messiah, charismatic leader, ‘just king’ (or whoever pretends to his crown), or – to continue our Indonesian illustration – the nationalist intellectuals headed by Sukarno who grafted themselves upon this movement, such phenomena are likely to subside, leaving behind them at best rearguard actions by backwoods guerrillas.

Still, when banditry and its companion, millennial exaltation, have reached such a peak of mobilization, the forces which turn revolt into a state-building or society-transforming movement do as often as not appear. In traditional societies accustomed to the rise and fall of political regimes which leave the basic social structure unaffected, gentry, noblemen, even officials and magistrates, may recognize the signs of impending change and consider the time ripe for a judicious transfer of loyalties to what will no doubt turn out to end with a new set of authorities, while expeditionary forces will think of changing sides. A new dynasty may arise, strong in the mandate of heaven, and peaceable men will settle down to their lives again, with hope, doubtless eventually with disillusion, reducing the bandits to the minimum of expected outlawry and sending the prophets back to their hedge-preaching. More rarely, a Messianic leader will appear to build a temporary New Jerusalem. In modern situations, revolutionary movements or organizations will take over. They too may well, after their triumph, find bandit activists drifting back into marginal outlawry, to join the last champions of the old way of life and other ‘counter-revolutionaries’ in increasingly hopeless resistance.

How indeed do social bandits come to terms with modern revolutionary movements, so remote from the ancient moral world in which they exist? The problem is comparatively easy in the case of national independence movements, since their aspirations can be readily expressed in terms comprehensible to archaic politics, however little they have in common with these in fact. This is why banditry fits into such movements with little trouble: Giuliano turned with equal ease into the hammer of the godless Communists and the champion of Sicilian separatism. Primitive movements of tribal or national resistance to conquest may develop the characteristic interplay of bandit guerrillas and populist or millennial sectarianism. In the Caucasus, where the resistance of the great Shamyl to the Russian conquest was based on the development of Muridism among the native Moslems, Muridism and other similar sects were said even in the early twentieth century to provide the celebrated bandit-patriot Zelim Khan (see p. 49 above) with aid, immunity and ideology. He always carried a portrait of Shamyl. In return, two new sects which sprang up among the Ingush mountaineers in that period, one of militants for holy war, the other of unarmed quietists, both equally ecstatic and possibly derived from the Bektashi, regarded Zelim Khan as a saint.7

It does not take much sophistication to recognize the conflict between ‘our people’ and ‘foreigners’, between the colonized and the colonizers. The peasants of the Hungarian plains who formed the bandit guerrillas of the famous Sandor Rózsa after the defeat of the revolution of 1848–9 may have been moved to rebellion by adventitious acts of the victorious Austrian regime, such as military conscription. (Reluctance to become or remain a soldier is a familiar source of outlaws.) But they were nevertheless ‘national bandits’, though their interpretation of nationalism might have been very different from the politicians’. The famous Manuel Garcia, ‘King of the Cuban countryside’, who was reputed single-handed to keep ten thousand soldiers occupied, naturally sent money to the father of Cuban independence, Martí, which the apostle refused, with the habitual dislike of most revolutionaries for criminals. Garcia was killed by treason in 1895, because – so Cuban opinion still holds – he was about to throw in his lot with the revolution.

National liberation bandits are therefore common enough, though commoner in situations where the national liberation movement can be derived from traditional social organization or resistance to foreigners than when it is a novel importation by schoolmasters and journalists. In the mountains of Greece, barely occupied, never effectively administered, the klephtes played a larger part in liberation than in Bulgaria, where the conversion to the national cause of eminent haiduks such as Panayot Hitov was notable news. (But then, the Greek mountains were allowed a fair measure of autonomy, through the formations of armatoles, technically policing them for the Turkish overlords, in practice doing so only when it suited them. Today’s armatole captain might be tomorrow’s klephtic chief, and the other way round.) What part they play in national liberation is another question.

It is harder for bandits to be integrated into modern movements of social and political revolution which are not primarily against foreigners. Not because they have any more difficulty in understanding, at least in principle, the slogans of liberty, equality and fraternity, of land and freedom, of democracy and communism, if expressed in language with which they are familiar. On the contrary, these are no more than evident truth, the marvel being that men can find the right words for it. ‘Truth tickles everyone’s nostrils,’ says Surovkov, the savage Cossack, listening to Isaac Babel reading Lenin’s speech from Pravda. ‘The question is how it’s to be pulled from the heap. But he goes and strikes at it straight off, like a hen pecking at a grain.’ It is that these evident truths are associated with townsmen, educated men, gentry, with opposition to God and Tsar, i.e. with forces normally hostile or incomprehensible to backward peasants.

Still, the junction can be made. The great Pancho Villa was recruited by Madero’s men in the Mexican Revolution, and became a formidable general of the revolutionary armies. Perhaps of all professional bandits in the Western world, he was the one with the most distinguished revolutionary career. When the emissaries of Madero visited him, he was readily convinced, especially as he was the only local bandit they wanted to recruit to the cause, though he had shown no previous interest in politics. Madero was a rich and educated man. If he was on the side of the people, this proved that he was selfless and the cause therefore untarnished. A man of the people himself, a man of honour, and whose standing in banditry was itself honoured by such an invitation, how could he hesitate to put his men and guns at the disposal of the revolution?8

Less eminent bandits may have joined the cause of revolution for very similar reasons. Not because they understood the complexities of democratic, socialist or even anarchist theory (though the last of these contains few complexities), but because the cause of the people and the poor was self-evidently just, and the revolutionaries demonstrated their trustworthiness by unselfishness, self-sacrifice and devotion – in other words, by their personal behaviour. That is why military service and jail, the places where bandits and modern revolutionaries are most likely to meet in conditions of equality and mutual trust, have seen many political conversions. The annals of modern Sardinian banditry contain several examples. That is also why the men who became the Bourbonist brigand leaders in 1861 were often the same men who had flocked to the standard of Garibaldi, who looked, spoke and acted like a ‘true liberator of the people’.

Hence, where the ideological or personal junction between them and the militants of modern revolution can be made, the bandits may join the new-fangled movements as bandits or as individual peasants as they would have joined archaic ones. The Macedonian ones became the fighters of the Komitadji movement (the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization or Imro) in the early twentieth century, and the village schoolmasters who organized them in turn copied the traditional pattern of haiduk guerrillas in their military structure. Just as the brigands of Bantam joined the Communist rising of 1926, the generality of Javanese followed the secular nationalism of Sukarno or the secular socialism of the Communist Party, the Chinese ones Mao Tse-tung, who was in turn powerfully influenced by the native tradition of popular resistance.

How could China be saved? The young Mao’s answer was, ‘Imitate the heroes of Liang Shan P’o’, i.e. the free bandit guerrillas of the Water-Margin novel.9 What is more, he systematically recruited them. Were they not fighters, and in their way socially conscious fighters? Did not the ‘Red Beards’, a formidable organization of horse-thieves which still flourished in Manchuria in the 1920s, forbid its members to attack women, old people and children, but obliged them to attack all civil servants and official personages, but ‘if a man has a good reputation we shall leave him one half of his property; if he is corrupt we shall take all his possessions and baggage’? In 1929 the bulk of Mao’s Red Army seems to have been composed of such ‘declassed elements’ (to use his own classification, ‘soldiers, bandits, robbers, beggars and prostitutes’). Who was likely to run the risk of joining an outlaw formation in those days except outlaws? ‘These people fight most courageously,’ Mao had observed a few years earlier. ‘When led in a just manner, they can become a revolutionary force.’ Did they? They certainly gave the young Red Army something of the ‘mentality of roving insurgents’, though Mao hoped that ‘intensified education’ might remedy this.

We now know that the situation was more complicated than that.10 Bandits and revolutionaries respected each other as outlaws with common enemies, and for much of the time roving Red Armies were not in a position to do more than what was expected of classic social bandits. However, both distrusted each other. Bandits were unreliable. The Communist Party continued to think of He Long, a bandit chief who became a general, and his men as ‘bandits’ who might defect at any moment, until he actually joined the Party. That may be partly because the lifestyle of a prosperous bandit chief hardly fitted in with the puritan expectations of the comrades. Still, while individual bandits and the occasional chief might be converted, unlike the revolutionaries, institutionalized banditry can work with the prevailing power structure as easily as it can reject it. ‘Traditionally (Chinese banditry) formed the rudimentary stage in a process that could lead, under the right conditions, to the formation of a rebel movement whose objective was to gain the ‘‘Mandate of Heaven’’. In itself, though, it was not a rebellion and certainly not revolution.’ Banditry and Communists met, but their ways diverged.

Undoubtedly political consciousness can do much to change the character of bandits. The communist peasant guerrillas of Colombia contain some fighters (but almost certainly not more than a modest minority) who have transferred to them from the former freebooting brigand guerrillas of the Violencia. ‘Cuando bandoleaba’ (When I was a bandit) is a phrase that may be heard in the conversations and reminiscences that fill so much of a guerrilla’s time. The phrase itself indicates the awareness of the difference between a man’s past and his present. However, probably Mao was too sanguine. Individual bandits may be easily integrated into political units, but collectively, in Colombia at least, they have proved rather unassimilable into left-wing guerrilla groups.

In any case as bandits their military potential was limited, their political potential even more so, as the brigand wars in southern Italy demonstrate. Their ideal unit was less than twenty men. Haiduk voivodes leading more than this were singled out in song and story, and in the Colombian violencia after 1948 the very large insurgent units were almost invariably communist rather than grass-roots rebels. Panayot Hitov reports that the voivode Ilio, faced with two to three hundred potential recruits, said this was far too many for a single band and they had better form several; he himself chose fifteen. Large forces were, as in Lampião’s band, broken up into such sub-units, or temporary coalitions of separate formations. Tactically this made sense, but it indicated a basic incapacity of most grass-roots chiefs to equip and supply large units or to handle bodies of men beyond the direct control of a powerful personality. What is more, each chieftain jealously protected his sovereignty. Even Lampião’s most loyal lieutenant, the ‘blond devil’ Corisco, though remaining sentimentally attached to his old chief, quarrelled with him and took his friends and followers away to form a separate band. The various emissaries and secret agents of the Bourbons who tried to introduce effective discipline and co-ordination into the brigand movement in the 1860s were as frustrated as all others who have attempted similar operations.

Politically, bandits were, as we have seen, incapable of offering a real alternative to the peasants. Moreover, their traditionally ambiguous position between the men of power and the poor, as men of the people but contemptuous of the weak and the passive, as a force which in normal times operated within the existing social and political structure or on its margins, rather than against it, limited their revolutionary potential. They might dream of a free society of brothers, but the most obvious prospect of a successful bandit revolutionary was to become a landowner, like the gentry. Pancho Villa ended as a hacendado,* the natural reward of a Latin American aspirant caudillo,† though no doubt his background and manner made him more popular than the fine-skinned Creole aristocrats. And in any case, the heroic and undisciplined robber life did not fit a man much for either the hard, dun-coloured organization-world of the revolutionary fighters or the legality of post-revolutionary life. Few successful bandit insurgents seem to have played much of a role in Balkan countries they had helped to liberate. Often enough the heroic memories of freedom in the pre-revolutionary mountains, and national insurrection, merely lent an increasingly ironic glitter to strong-arm gangs in the new state, at the disposal of rival political bosses when they did not do a little freelance kidnapping and robbery for their private purposes. Nineteenth-century Greece, nourished on the klephtic mystique, became a gigantic spoils-system, whose prizes were thus competed for. The romantic poets, folklorists and philhellenes had given the highland brigands a European reputation. M. Edmond About, in the 1850s, was more struck by the shoddy reality of the ‘Roi des Montagnes’ than by the high-flown phrases of klephtic glory.

The bandits’ contribution to modern revolutions was thus ambiguous, doubtful and short. That was their tragedy. As bandits they could at best, like Moses, discern the promised land. They could not reach it. The Algerian war of liberation began, characteristically enough, in the wild mountains of the Aurès, traditional brigand territory, but it was the very unbandit-like Army of National Liberation which finally won independence. The Chinese Red Army soon ceased to be a bandit-like formation. More than this. The Mexican Revolution contained two major peasant components: the typical bandit-based movement of Pancho Villa in the north, the mainly unbandit-like agrarian agitation of Zapata in Morelos. In military terms, Villa played an immeasurably more important part on the national scene, but neither the shape of Mexico nor even of Villa’s own north-west was changed by it. Zapata’s movement was entirely regional, its leader was killed in 1919, its military forces were of no great consequence. Yet this was the movement which injected the element of agrarian reform into the Mexican Revolution. The brigands produced a potential caudillo and a legend – not least, a legend of the only Mexican leader who tried to invade the land of the gringos in this century.* The peasant movement of Morelos produced a social revolution; one of the three which deserve the name in the history of Latin America.