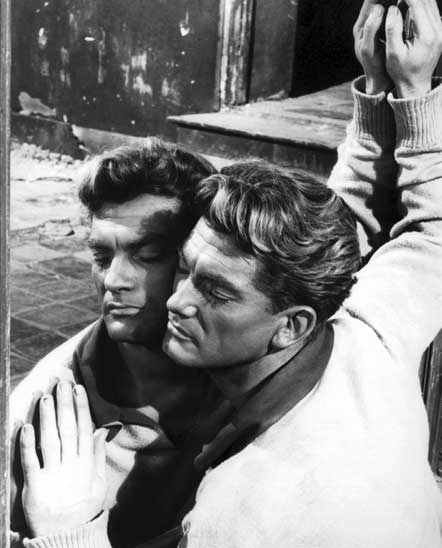

Teen rebels get close: Sal Mineo (left) with James Dean

From the days of Chaplin-era silents, through the early talkies, into the changing – though not always progressively so – standards of the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, gay characters were stereotypically portrayed as stock sissy caricatures, humorous swishy sidekicks and tragic figures to be pitied.

‘Hey, you wanna come home with me? … If you wanna come, we could talk and then in the morning we could have breakfast…’

Plato (Sal Mineo) to Jim (James Dean) in Rebel Without a Cause

Welcome to one very large pre-60s closet…

Homosexual imagery can be traced back to the very start of American cinema, with the Thomas Edison film The Gay Brothers (1895), directed by William Dickson, in which two men dance together while a third plays the fiddle. In fact, this primitive test is one of the earliest surviving motion picture images.

Female impersonators and women playing male roles began appearing in films of the early 1900s, such as the Vitagraph release The Spy (1907), the feminist satire When Women Win (1909), or DW Griffith’s Getting Even (1909). However, looking at this work today, the imagery can seem more overtly gay or lesbian than it did in its time, when the notion of homosexual desire was more strictly taboo.

By the teens, American silent comedies began relying on the audience’s recognition of homosexual types and filmmakers began to feature the ‘sissy’. One of Hollywood’s original stock characters, the sissy was the one who everyone laughed at. So in the films of the teens and 20s, homosexuality was, quite literally, a joke.

In A Florida Enchantment (1914), two women dance off together, leaving their bewildered menfolk to shrug their shoulders and dance off together themselves. Meanwhile, even one of cinema’s greatest stars was facing a challenge to his masculinity. In Behind the Screen (1916), Charlie Chaplin is seen kissing Edna Purviance passionately when she’s disguised as a boy; that is until bully Eric Campbell spots them and starts mocking the pair as two gay lovers.

In the spoof westerns of the 1920s, the limp-wristed sissy was dropped into the macho cowboy world for comic effect. In The Soilers (1923), a parody of the rugged western The Spoilers, made in the same year, the laughs come from a gay cowboy who adores the macho men around him. Later, Stan Laurel played the pansy creating consternation in With Love and Hisses (1927), and together with Oliver Hardy starred in Liberty (1929), as escaped prisoners who shed their prison uniforms but inadvertently slip on each other’s trousers. The farce involves the duo trying to hide and swap pants, but whatever they do and wherever they go to do this, they are constantly caught with their pants down by shocked passers-by.

‘Listen, sister, when are you going to get wise to yourself?’

Miriam in The Women

Lesbian references in film also began in the late 20s and into the 30s. Step forward Countess Geschwitz (Alice Roberts), the first movie lesbian in Pandora’s Box (1929), although this character was deleted from British and American versions of the German film. Later, in 1931, also from Germany, came Maedchen in Uniform, in which a young girl’s crush on her female schoolteacher becomes public knowledge at a boarding school. Probably the most famous early lesbian film, Maedchen in Uniform was the first to be seen publicly in America and the UK and was the first in a long line of lesbian-themed films set in boarding schools.

‘Fasten your seat belts, it’s going to be a bumpy night.’

Margo (Bette Davis) in All About Eve

Meanwhile, back in America, a tuxedoed Marlene Dietrich caused a storm when, in the 1930 film Morocco, she finished a song in a nightclub by kissing a young woman in the audience full on the lips. And Greta Garbo raised eyebrows with her portrayal of Queen Christina (1933), based around the inner conflicts of a Swedish lesbian ruler. While the film invented a hetero romance with John Gilbert, hints of lesbianism remained, most notably in her affectionate relationship with her lady-in-waiting. Christina kisses Elizabeth Young, and claims she’ll die not an old maid but ‘a bachelor’. Hollywood glanced again at lesbianism with the women’s-prison film Caged (1950); and in the same year came All About Eve, whose title character’s lesbianism was obvious to those in the know.

As for the men, the first years of sound saw – and heard – the same sissy characters of the silent era, with more clichéd images in such films as The Gay Divorcee (1934), Call Her Savage (1932) and Top Hat (1935); and character actors like Edward Everett Horton and Eric Blore began to make a name for themselves through playing pansies whose humour was all based around effeminacy.

In the mid-1930s, however, Hollywood decided to begin censoring its own films. The result was the infamous Hays Code, led by Postmaster General Will Hays, and while the Code didn’t manage to completely eliminate the presence of gay characters in films, it ensured that filmmakers had to make them less obvious. So around this time writers and directors ditched the in-your-face camp sissy for another type of homosexual character: the unhappy, suicidal, desperate figure whose inevitable end was to be destroyed. In Tea and Sympathy (1956) even the false accusation of ‘Sissy Boy’ was enough to nearly destroy the character. For decades, anyone of questionable sexuality would meet with a bad end by the close of the last reel. Gay characters found their natural comeuppance via bullets, fire or suicide.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948)

Another image of the homosexual was as victimiser rather than victim, the shadowy psychopath, cold-hearted villain or perverted killer. This is a cliché resonating through such films as Dracula’s Daughter (1936) and Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948). Hitchcock, always fascinated by the darker byways of sexuality, was a master of sneaking gay-shaded content past the censors and Rope was a barefaced attempt to pull the wool over their eyes. The director knew exactly what he was doing and slyly cast gay actors John Dall and Farley Granger in the parts of gay child-killers Leopold and Loeb. Scripted by Arthur Laurents, his film both perpetuated and subverted homosexual stereotyping.

So although the Production Code was aimed at curbing social change and banning all reference to sexual diversity, filmmakers like Hitchcock were still getting away with it. Interestingly, if Hitchcock had been a filmmaker in France or Italy, he wouldn’t have had to worry about the censors. In Europe, writers and directors were free to make great gay-interest films: Luchino Visconti completed the brilliant, Italian-based production Ossessione (1943); and in France, Jean Cocteau made the magical Orphée (1950). One exception, though, was Jean Genet’s French production, Un chant d’amour (1950), which was simply too explicit and remained unseen for decades.

Back in Britain and the US, gay characters were visible only through subtext and innuendo. Reined in by the Code, the prudishness of studio executives, and the pressures of social conformity, moviemakers learned to write between the lines. And audiences learned to view the films that way.

As soon as filmmakers wrote on the lines rather than between them, they were caught out. The Hays Production Code Director, Joe Breen, was successful in making many producers play by the rules. When Lillian Hellman’s play The Children’s Hour was filmed in 1936 by director William Wyler, its lesbian theme was cut and the film re-titled These Three; the sexual confusion strand in The Lost Weekend (1945) was also cut, as was the gay-bashing subject matter in Crossfire (1947).

Therefore most of the pre-1960s homosexual content only found its way into movies that simply winked at the audience. If you got the joke, you were one step ahead of the morality taskmasters behind the scenes. Take, for instance, Peter Lorre in The Maltese Falcon (1941). Or the John Wayne western Red River (1948), where six-shooters are phallic playthings and John Ireland says to Montgomery Clift, ‘There are only two things more beautiful than a good gun: a Swiss watch, or a woman from anywhere. You ever had a Swiss watch?’

‘There are only two things more beautiful than a good gun: a Swiss watch, or a woman from anywhere. You ever had a Swiss watch?’

John Ireland to Montgomery Clift in Red River

Censors were even fooled by directors who made epics from the era of Hollywood’s studio system. Stanley Kubrick’s epic Spartacus (1960), for example, included an attempt by Roman general Laurence Olivier to seduce his slave Tony Curtis as they shared a bath, yet this ‘snails and oysters’ scene was cut and remained unseen until the film’s 1991 restoration and re-issue. Then there’s the gay subtext in Ben-Hur (1959) that subsequently sent Charlton Heston’s blood pressure soaring.

During the 1950s, with ‘masculinity’ on the up, the vitriol against being gay grew more pronounced. One of the biggest stars of the era, Rock Hudson, like many male stars of the silver screen, had to be very careful to keep his homosexual experiences and lifestyles firmly in the closet. He is now known to have had gay affairs and in the latter part of the 50s a scandal sheet threatened to out him. His studio hastily arranged a sham marriage that lasted just three years. There were always teasers though, sprinkled by scriptwriters, throughout Hudson’s movies of the 50s and 60s. Scenes in Pillow Talk (1959) involve Hudson having to drag up and get into bed with Tony Randall because his character poses as gay in order to get a woman into bed. A gay man impersonating a straight man impersonating a gay man – all very amusing to those in the know at the time. Similarly, in Lover Come Back (1961), Hudson feigns impotence and says, ‘Now you know why I’m afraid to get married’.

At the time, Hudson’s fans wouldn’t have given a second thought to the notion that he was really gay. It wasn’t until 1984, when the actor revealed he had AIDS, that his sexuality became public. He died a year later.

Lover Come Back (1961)

Slightly more nonchalant about his experiences in the 50s and early 60s was Marlon Brando who was rumoured to be carrying on an affair with the actor Wally Cox. Later, the Hollywood great admitted: ‘I have had homosexual experiences and I’m not ashamed.’

James Dean, who worshipped the ground Brando walked on, was known to frequent various backroom gay bars in LA and also dated several influential Hollywood execs. In his 1994 autobiography Songs My Mother Taught Me, Brando said he thought that Dean based his acting on his and his lifestyle on what he thought Brando’s was. On the night before his death, at a Malibu party, it was reported Dean had stormed off after an argument with either a lover or friend over the actor dating women for ‘publicity purposes’.

‘If I had one day when I didn’t have to be all confused and I didn’t have to feel that I was ashamed of everything. If I felt that I belonged someplace. You know?’

Jim (James Dean) in Rebel Without a Cause

Another real American teen rebel in the 50s was Sal Mineo, who co-starred opposite James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955). He played a rich, lonely, gay teenager called Plato who’s not only in love with Alan Ladd (whose picture is pinned to his school locker), but also with his only friend, Jim, played by Dean. For his tender, soulful performance as the abandoned Plato, he earned a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award nomination. Unlike many of his ‘confused’ contemporaries, Mineo was probably the first major actor in Hollywood to publicly admit his homosexual lifestyle, and was a pioneer in paving the way for future generations of gay actors. It was rumoured for years that Mineo’s 1976 knifing death was a result of his homosexual lifestyle. But in 1979, the killer was caught and convicted and it turned out Mineo was actually the victim of a robbery.

Unlike Mineo, one of the most handsome actors of the 50s, Montgomery Clift, kept his homosexuality quiet from his adoring public. Clift managed to get police charges for picking up a hustler on 42nd Street dropped so as to protect his on-screen persona. But his gay lifestyle was well known in Hollywood, and on the set of The Misfits (1961) Clark Gable referred to his co-star as ‘that faggot’. Like James Dean and Sal Mineo, Clift died young. But Clift’s death seemed to be brought about by the sheer torment he put himself through over his gayness. Eventually, through a mixture of drink and drugs, he died of a heart attack in 1966, aged 46.

While Montgomery Clift had pretty-boy good looks, Clifton Webb, another popular Hollywood actor of the 50s, wasn’t traditionally handsome but more the suave, sophisticated type. Webb’s sexual preferences were no secret amongst Hollywood circles; several young, fit actors reportedly came to him for a helping hand, most notably James Dean.

‘Yeah, it’s sad, believe me missy; when you’re born to be a sissy… I’m afraid there’s no denying; I’m just a dandy lion.’

The Cowardly Lion (Bert Lahr) in The Wizard of Oz

Back in Britain, actors were also finding it difficult to be open and honest about their gay lifestyles. The Carry On stars Kenneth Williams and Charles Hawtrey played sissies on screen throughout the 50s, but in private both were finding it tough to come to terms with their sexuality. Hawtrey turned to drink while Williams preferred to socialise with friends, opting for a sexless life without lovers. Another British comedian, Frankie ‘titter-ye-not’ Howerd, was gay but preferred to present an on-screen image of a man never happier than when surrounded by a bevy of buxom beauties.

‘But, you’re not a girl! You’re a guy, and, why would a guy wanna marry a guy?’

Joe in Some Like it Hot

Gay audiences, like many of the stars they paid money to see, were also having to deal with life in the closet. In the 30s, gay men had latched on to the gay code dialogue in films like The Wizard of Oz (1939) and worshipped divas such as Judy Garland, Joan Crawford and Bette Davis. But even by the 50s, they were struggling to find gay-interest material in the movies. However, the clues were certainly there.

In Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), one scene shows a gym full of bodybuilders working out and they have no interest whatsoever in Jane Russell who strolls through – and the well-oiled men are singing ‘Ain’t There Anyone Here for Love?’ Meanwhile, in the 1959 Hollywood gender-bending comedy Some Like it Hot, Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon have the time of their lives dragging up. When Lemmon, disguised as Daphne, tries to persuade Osgood (Joe E Brown) that they can’t get married because Lemmon is really a man, Osgood remains unfazed, declaring, ‘Nobody’s perfect!’

San Francisco drag party, circa 1959, from Before Stonewall: The Making of A Gay and Lesbian Community (1984)

By the end of the 50s, after lengthy discussions, the Motion Picture Production Code Office finally granted a special dispensation permitting Suddenly, Last Summer (1959) to include the first male homosexual in an American film. The Production Code board felt they could compromise on the theme of homosexuality as long as it was ‘inferred but not shown’. So the ‘H’ word was never uttered, the gay character never spoke, and his face was never shown on screen. Nevertheless, director Joseph L Mankiewicz’s film was a huge milestone. As the 60s approached it looked like the Production Code Administration was beginning to lose interest in its traditional hostility towards gay material.

‘Is that what love is? Using people? And maybe that’s what hate is – not being able to use people.’

Catherine in Suddenly Last Summer

Germany, 100 mins

Director: GW Pabst

Cast: Louise Brooks, Franz Lederer, Fritz Kortner

Genre: Silent lesbian-interest drama

Based on two Frank Wedekind plays, Erdgeist and Die Büchse der Pandora, Pandora’s Box is widely considered the finest film of its director, GW Pabst – an extremely significant figure of silent and early 30s cinema.

A silent screen classic, it’s about a girl with loose morals who drifts from promiscuity to whoredom – and she’s only interested in one thing: pleasure. One night she makes the fatal mistake of catching the eye of Jack the Ripper.

The film’s portrait of a shameless callgirl surrounded by exploitative characters met with anger and derision at the time of its original release. Perhaps the reaction was something to do with the film’s open critique of bourgeois sexual hypocrisy, its inclusion of the source’s lesbianism (watch for an eloquently erotic dance scene that reminds us of Bertolucci’s The Conformist) and adherence to Wedekind’s Lulu as a ‘personification of primitive sexuality who inspires evil unawares’.

Upon its release, Pandora’s Box largely failed in Germany and was barely reviewed in the United States. The style of the film’s star, Louise Brooks, was so natural that critics complained she either couldn’t or didn’t act.

However, Pandora’s Box is now celebrated by most critics around the world and considered a landmark of the silent cinema, distinguished by expert compositions and expressionist lighting, along with the director’s typically fluid editing that subtly cuts on movement to promote a sense of inescapable momentum towards an ultimate tragic destiny.

And then, of course, there’s the cult of Louise Brooks. Central to the movie’s success is her legendary performance as Lulu, the most fatale of all femmes. With a heightened naturalistic style and dark, dark, noirish leanings, the remorseless and fascinating journey of the anti-heroine to her date with destiny, in the form of a man who may be Jack the Ripper, exudes an hypnotic fascination.

Brooks is a twentieth-century icon. Her hair is her trademark. Universally recognised for a distinctive bob, its influence extended to the ‘do’ sported by Uma Thurman’s Mia Wallace in Pulp Fiction. Brooks was later rediscovered and deservedly so. She certainly lights up this expressionistic slice of fatalism with incandescent star power.

Louise Brooks (centre) in Pandora’s Box

Pandora’s Box was considered such strong stuff that it was banned in several countries. Although it now feels pretty safe, it’s easy to see what caused the censors to wince. Lesbianism, stripping serial killers – with so much of modern movie life here, the picture, like Brooks’s beauty, defies the ravages of time.

Germany, 110 mins

Director: Leontine Sagan

Cast: Hertha Thiele, Emilia Unda, Dorothea Wieck, Hedwig Schlichter

Genre: Lesbian drama

Based on the play Yesterday and Today by lesbian poet Christa Winsloe, Maedchen in Uniform is the stunning story of a girl called Manuela (Hertha Thiele) who is sent to a boarding school for daughters of Prussian military officers. There, she rejects the repressive atmosphere and finds comfort in a tender relationship with one of the teachers, Fraulein von Bernburg (Dorothea Wieck). While the headmistress declares Manuela’s affections to be scandalous, her classmates are supportive.

An enduring lesbian classic, avant-garde director Leontine Sagan’s film was immensely popular around the world when it was released in 1931. It was voted best film of the year in Germany while in New York a critic for the World Telegram dubbed it ‘the year’s ten best programs all rolled into one’.

Powerful and mature treatment of lesbian themes, coupled with erotic images and condemnation of authority, puts this all-female feature into the ranks of important cinema, presaging as it does the rise of conformity and oppression through Nazism.

Sagan’s film was the first in a long line of lesbian-themed films set in boarding schools. Later, a 1958 remake featured actresses of international status (Romy Schneider, Lilli Palmer, Christine Kaufmann) but, although it was much more lavish, it didn’t match the power of the original.

US, 132 mins

Director: George Cukor

Cast: Joan Crawford, Norma Shearer, Rosalind Russell, Mary Boland, Paulette Goddard, Joan Fontaine

Genre: Comedy

Having been fired by producer David O Selznick from the set of Gone with the Wind after just three weeks, director George Cukor was handed the opportunity to direct MGM’s The Women. Adapted by Anita Loos and Jane Murfin from Claire Boothe’s hit Broadway play, the story required an all-female cast of 135, giving Cukor a great excuse to exploit the professional rivalries between the studio’s stable of stars.

The result is a gloriously camp and memorably bitchy work, a scathing story of love, betrayal and revenge. Starring Norma Shearer and Joan Crawford (long-time rivals at MGM), The Women is a Hollywood comedy of the Golden Age.

The plot centres around Mary Haines (Shearer), a member of New York’s high society who discovers that her husband is having an affair with gold-digger Crystal (Crawford). Mary’s mother advises her to say nothing and wait for Stephen to get bored of his new catch, but so-called ‘friends’, including the vindictive Russell, relish gossiping about Mary’s humiliating predicament. After a confrontation with her rival-in-love at a fashion show, she heads off to Reno to get a quickie divorce. The news that Stephen has married Crystal confirms her worst fears, yet, in time, Mary develops the ruthless instincts necessary to try and win back her spouse.

Aside from what little plot there is, the film is basically an excuse for lots of megastars to exchange witty insults with each other. Cukor entered Hollywood when the talkies started as a dialogue director; and this is about as talky as any film you’ll see. But just pay attention because this movie starts with a frenzy of dialogue and never really slows down. Lots of laughs, some good performances, and endless bitching and cattiness. A sugar-rush of pre-post-feminist comedy, this was Sex and the City for the 30s.

As in the play, no man appears – so it’s a field day for the gals to romp around in panties and gowns. The acid-tongued one-liners delivered by Crawford et al are very funny and most of the members of the cast deport themselves in a manner best described by her at the end: ‘There’s a name for you ladies, but it’s not used in high society outside of kennels’.

The Women, however, is a mass of contradictions in the way it both endorses and critiques patriarchal values. In the bizarre opening credits each actress is represented by a different animal that conveys their character’s essential nature (Shearer is a fawn, Crawford a leopard, Russell a panther), and throughout much stress is laid upon the notion that women are inevitable rivals in their competition to win, and maintain their hold on, men. ‘Don’t confide in your girlfriends’, admonishes Mary’s mother. ‘If you let them advise you, they’ll see to it in the name of the friendship that you lose your husband and your home.’

Despite the conservative conclusion, Cukor’s film still has a subversive potency in the way it undermines traditional notions of romantic love and the ‘naturalness’ of marriage. In the bad old days of the Code, this bitch-fest was about as gay as it could get without actually mentioning the word. Extolling the joys of the single life, near the end of the movie co-star Lucile Watson enthuses: ‘It’s marvellous to be able to spread out in bed like a swastika!’

US, 102 mins

Director: Victor Fleming

Cast: Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke, Jack Haley

Genre: Musical

‘Lions and tigers and bears, oh my!’ From the book by L Frank Baum, and springing from MGM’s golden era with a then-staggering production budget of $3 million, The Wizard of Oz is everybody’s cherished-favourite, perennial-fantasy film musical and has been the ‘family classic’ for decades. Its images – the yellow brick road, the Kansas twister, the Land of Oz – and characters such as Auntie Em, Toto, Dorothy, the Tin Woodman and the Munchkins, as well as the film’s final line – ‘There’s no place like home’ – and great songs such as Over the Rainbow, have gone down in cultural history.

One of the most popular and beloved motion pictures of all time, it has probably been seen by more people than any other over the decades. Yet there’s no denying the film is also a gay favourite with the appropriation of its rainbow iconography and much of its dialogue becoming camp cliché and gay code.

Dorothy with friends

As farm girl Dorothy Gale, Judy Garland endeared herself to the hearts of filmgoers for generations. The musical fantasy begins in black and white but soon whisks her on a Technicolor trip to the incredible land of Oz. Dorothy dreams of somewhere far away from the drab hog farm, a rainbow world where she can express herself and follow her dreams. How many gay guys aren’t going to identify with that?

For generations of gay men growing up in backward-thinking small towns, escape has always been priority number one, the desire to get out of Humdrum Village and seek out a whole new world, whether it be in London, Manchester, New York, San Fran… or perhaps Oz.

On screen we are captivated by an adventure story which sees young Dorothy and her cute little dog Toto caught in a twister and whisked away from their Kansas home into an eerie land. There, she encounters strange beings, good and evil fairies (Billie Burke and Margaret Hamilton) and prototypes of some of the adults who comprised her farm world. Along the way, she’s helped by her companions, the Scarecrow (Ray Bolger), the Tin Woodman (Jack Haley) and the Cowardly Lion (Bert Lahr). She faces a long trek, following the Yellow Brick Road, to the castle for an encounter with the mighty but wonderful Wizard of Oz (Frank Morgan), where she and her new friends will seek fulfilment of desire.

The film consists mainly of an extended dream sequence, the dream of a young girl, although it could just as easily be that of an old queen. Indeed, Dorothy’s journey into fantasyland has resonated throughout the gay community over the years. The expression ‘a friend of Dorothy’ is one many gay men use to describe themselves and other gay people; the Garland reference ‘My Judy’ is often used by gay men to describe their best friend; and many gay bars around the world are still named after references to the film.

So why do gay men love all things Oz?

Most fear ‘coming out’ and if they’re out they’ll certainly remember that fear. In The Wizard of Oz the underlying theme of conquest of fear is subtly thrust through the action, so it’s not surprising that gay fans of the film get hooked into the quest of its earnest central character. Dorothy finds herself in a dangerous world of people who either don’t understand or appreciate her, or who are simply out to get her. Donning a pair of glittering red shoes, she hooks up with a motley crew of eccentric characters who are also seeking some kind of new life. A new non-biological family is formed, and a series of fantastic adventures unfolds. Gay men coming out onto the scene are also experiencing this kind of radical transformation, from a black-and-white conventional closeted world to a colourful, exciting and sometimes-freakish place, filled with other loners trying to discover themselves. The Land of Oz holds a special allure for those who are different because it’s a community of eccentrics, a place that’s fiercely tolerant of the outlandish. In the end, we see that the Scarecrow really is smart, the Lion is brave and the Tinman does have a heart – all they lacked was self-esteem.

The involvement of gay icon Judy Garland must also add to the movie’s appeal, certainly with the older generation. The actress led a life of emotional turmoil and MGM made her take vast amounts of pills to help her through relentless filming schedules. Garland’s tragic later life (she died of an overdose in 1969) makes her naïve and utterly beguiling Dorothy seem all the more poignant in retrospect.

Whatever the reasons for its popularity, Oz is an indelible part of our consciousness and our earliest childhood memories. The movie endures despite modern advances in film make-up and special effects and has become a TV classic, always pulling in high ratings, especially at Christmas. Just to hear ‘Over the Rainbow’ once again is worth tuning in for alone.

But all great films deserve to be seen on the big screen and, with that in mind, one gay film festival, ‘Outsiders’, based in Liverpool, recently showcased The Wizard of Oz in very special circumstances. A new digital print of the film was created with the music track stripped out leaving the voices and sound effects intact, and it was shown with live accompaniment from the Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by John Wilson. Fans attending were also asked to break out their ruby slippers and come dressed as their favourite Oz character.

In addition to such special screenings, The Wizard of Oz was also brought back onto the cultural scene in 2006 with the opening of Wicked, a smash-hit Broadway musical which told the ‘back story’ of the witches of Oz, Elphaba the Wicked Witch and Glinda the Good Witch. Based on a novel by the gay author Gregory Maguire, the show later transferred to London’s West End where it has enjoyed similar success.

Although nominated for Best Picture back in 1939, the Victor Fleming movie didn’t win. Some Oscars, however, were awarded to Oz: Special Award to Judy; Best Original Score (Herbert Stothart); and Best Song for ‘Over the Rainbow’. More recently the song claimed the number one spot in The American Film Institute’s list of ‘The 100 Years of The Greatest Songs’. The AFI board said ‘Over the Rainbow’ had captured the nation’s heart and echoed beyond the walls of a movie theatre.

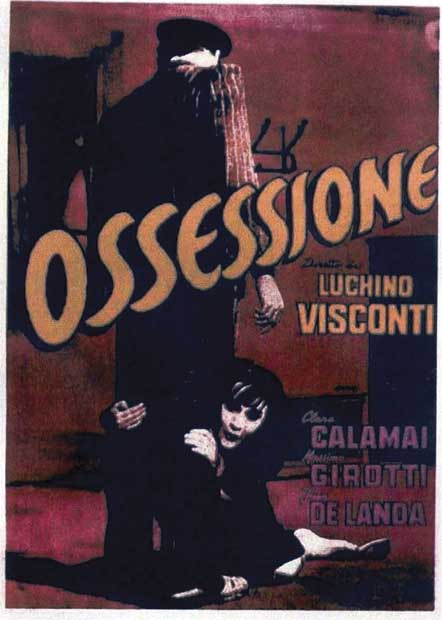

Italy, 160 mins

Director: Luchino Visconti

Cast: Massimo Girotti, Clara Calamai, Elio Marcuzzo

Genre: Neorealist drama

The Postman Always Rings Twice has been filmed five times, and even staged as an opera, but Luchino Visconti’s version, his powerful first film, is an unauthorised – and partly homoeroticised – adaptation of James M Cain’s classic 1934 suspense novel. Not only is Ossessione one of the most engrossing suspense films ever made – and a landmark in the history of gay cinema – it also launched the extremely influential Neorealist movement in film, known for its rough, documentary-like technique, use of non-professional actors, and emphasis on working-class characters. Neorealism loosened up filmmaking styles around the world and it was, arguably, the most important development in cinema before the French New Wave.

In Ossessione, Visconti follows the main thrust of the original story, about a beautiful but frustrated wife Giovanna (Clara Calamai) who becomes obsessed with a strikingly handsome and virile drifter called Gino (Massimo Girotti) who’s staying at her inn. Trapped in a loveless marriage with her obese and ill-tempered husband, Giovanna begs Gino to help her kill him so that they can collect his hefty insurance premium. However, after the murder, they find themselves caught up in a downward spiral of fear, deception and jealousy.

Visconti, who also co-wrote the screenplay, adds a fascinating new element to the story in the form of a beguiling gay vagabond Lo Spagnolo (Elio Marcuzzo), who offers Gino a chance at a better life, both before and after the murder. Gino and Lo Spagnolo’s scenes, brimming with both sexual force and real tenderness, are astonishing for their period, and still deeply moving. Their relationship, as much as the illicit heterosexual pairing, may have caused the violent religious and political outrage which greeted the film. The Fascists went so far as to burn the negative; fortunately, Visconti was able to save a print. Because Visconti never secured the rights to Cain’s novel, the film was long banned in the US, not appearing until 1975.

Visconti, the great, openly gay filmmaker, has been called the most Italian of internationalists, the most operatic of realists, and the most aristocratic of Marxists (of noble lineage, he was nicknamed ‘the Red Count’). Although only a few of his twelve films contain important gay characters (Ossessione being one of them), they are essential to the evolution of gay cinema.

US, 109 mins

Director: Michael Curtiz

Cast: Joan Crawford, Zachary Scott, Jack Carson, Eve Arden, Ann Blyth, Bruce Bennett

Genre: Melodrama

More than a mere soap opera, this etched-in-acid film is a Joan Crawford classic, and was a triumph for her at a time when she’d been let go by studio MGM.

Ann Blyth (left) with Joan Crawford in Mildred Pierce

The film chronicles the flaws in the American dream as Mildred (Crawford) drives her husband away with financial nagging and then smothers her daughter with all the advantages she never had.

Mildred is a woman forced, after a failed marriage with Bert (Bennett), into waitressing. She succeeds in acquiring a chain of restaurants and enough money to satisfy spoiled, petulant daughter Veda (Blyth). ‘My mother… a waitress!’ she sneers. Next, enter the reptilian Monte (Scott), the owner of the property Mildred wishes to convert. Asked what he does, Monte replies, ‘I loaf, in a decorative and highly decorative manner.’ Monte, with his ‘beautiful brown eyes’ becomes Mildred’s hubby number two. But what’s a mom to do when she discovers that hubby is having an affair with his stepdaughter?

With its striking sets, bold cinematography and assured direction by Curtiz, Mildred Pierce is an undisputed classic. For sheer, unadulterated star power, Joan Crawford’s return to fame, fortune and an Oscar is unrivalled. The amazing thing about this adaptation of James M Cain’s bleak novel is that the entire cast and the surrounding talent also shine. There’s not a single dud moment.

The film’s appeal with gay film lovers lies with Crawford, a true diva and gay icon, and the fact it’s as camp as they come. Before Carry On films, before Absolutely Fabulous, before Divine, there was Mildred Pierce, a tale with more drama than you can shake a stick at. The film snaps and crackles with sarcastic dialogue, memorable characterisations, and Crawford herself – an aura of glamour clings to her throughout.

The campiest scenes include Mildred slaving away in her fast-food-waitress uniform, the ‘I wish you weren’t my mother’ tirade by her unruly daughter, and Mildred’s visit to the dingy burlesque club to see her daughter dancing all over 50s taboos.

US, 80 mins

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Cast: James Stewart, John Dall, Farley Granger, Cedric Hardwicke

Genre: Suspense thriller

Full of suspense and ingenious camerawork, Rope – Hitchcock’s first film in colour – is all set on one stage and unfolds in unprecedented long takes. With a story relating to a real-life case, this truly frightening classic concerns two college boys who in 1924 murdered another student just for the fun of it, and to see if they could get away with a motiveless crime.

The screenplay, by gay writer Arthur Laurents in collaboration with Hume Cronyn and Ben Hecht, is based on the play Rope’s End by Patrick Hamilton.

Hitchcock’s take on the Leopold-Loeb case has the young men (Dall, Granger) murder a friend for the hell of it, then hold a cocktail party where the guests include the victim’s father (Cedric Hardwicke), his fiancée (Joan Chandler) and the rest of his family. Plus the murderers’ tutor (James Stewart), who returns to unmask their arrogant crime.

Jean Renoir, the great filmmaker and acerbic critic, dismissed the movie saying, ‘It’s a film about homosexuals, and they don’t even show the boys kissing.’

However, watching Rope today is totally refreshing. Viewers should remember that, in the days of the Production Code, any mention of homosexuality was forbidden. Nevertheless, by casting gay actors John Dall and Farley Granger to play the parts of real-life gay child-killers Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, Hitchcock managed to pull the wool over the censors’ eyes. Incredibly, the executives at Warner Bros were unaware of the gay implications until it was too late and the film was completed. They held their breath as it went to the censors’ office and, amazingly, it slipped through the net.

Interestingly, Hitchcock wanted Montgomery Clift to play one of the murderers, with Cary Grant as the pair’s mentor. But the homosexual subtext hit too close to home for Grant and Clift, and they dropped out.

Innovative filmmaking at its best, Rope is more like the theatre, with little editing, only when there’s a change of time, a change of location or a change of point of view. Compared with the formulaic editing style of most of today’s American or British films, Hitchcock’s virtuoso long single takes and uninterrupted sequences are a welcome diversion. The experimental ten-minute takes serve to heighten the claustrophobia and tension of this disturbing thriller, allowing the action to unfold in the frame itself rather than movements created by editing. The audience can discover the heart of the material rather than allowing the camera to discover it for them.

The same story was filmed again ten years later as Compulsion (1959), directed by Richard Fleischer, with the homosexual aspect made more obvious. More recently, Tom Kalin’s version of events, released as Swoon (1992), delved even further into the two men’s self-destructive passion for each other.

France, 95 mins

Director: Jean Cocteau

Cast: Jean Marais, Maria Casares, Francois Perier, Juliette Greco

Genre: Surreal Allegory

Jean Cocteau’s fantastical updating of the Orpheus legend is cinematic poetry, a truly magical work. Unforgettable and profoundly influential, it defies comparison with anything else in cinema.

The French poet and filmmaker was prolific in the outpourings from his fertile imagination. Even today, over 50 years after his death, we can say, ‘Well, that’s straight from Cocteau,’ because he established such a distinctive style, a lyrical way of looking at the externalising of the inner world.

His fifth feature as director, Orphée is an hypnotically beautiful, allegorical retelling of the Greek myth set in post-war Paris, tantalisingly – and purposefully – open to myriad interpretations.

Cocteau believed that the cinema was a place of magic which enabled the artist to hypnotise an audience into dreaming the same dream. Here, Jean Marais is the object of desire and certainly many a gay man’s dream. Marais was Cocteau’s real-life boyfriend and one of the best-looking male stars of the era. In Orphée, he delivers an impressive performance as the eponymous poet, besieged by admirers, who hears voices from other worlds over the radio. He even meets Princess Death (Maria Casares), black gloved, when she comes through a mirror.

Cocteau makes brilliant use of a variety of cinematic effects, the most memorable of which is this mirror, representing the entrance to the hereafter: ‘We watch ourselves grow old in mirrors. They bring us closer to death.’

As well as the beautiful Marais, like most of Cocteau’s work, further queer iconography is there for all to admire: travelling between this world and the next via a chauffeur-driven Rolls Royce, Marais is escorted by a convoy of satanic, leather-clad motorcyclists, the errand boys of death.

In an article on Orphée, Cocteau affirmed that, ‘There is nothing more vulgar than works that set out to prove something. Orphée naturally avoids even the appearance of trying to prove anything.'

Orphée may well represent Jean Cocteau’s most accomplished work as a director, remarkably consistent with the rest of his work and faithful to his own personal obsessions. It is a film which explores dreams and desire and the proximity of life and death, reality and illusion. It also shows Cocteau’s total commitment to the world of his own artistry, which seems to have its own logic and its own laws. As the chauffeur in the film states: ‘It is not necessary to understand, it is necessary only to believe.’

France, 25 mins

Director: Jean Genet

Genre: Experimental

French novelist and playwright Jean Genet wrote and directed his only film, Un chant d’amour, in 1950. A hymn to homosexual desire, it has been hailed as one of the most important films in gay cinema.

Set in a French prison, two inmates in solitary confinement communicate their desires to one another, principally through a small hole in the wall that separates their cells, exorcising their frustration and loneliness under the voyeuristic gaze of the prison guard. In Genet’s silent, poetic and intensely physical vision of homosexual desire, the dynamic of warder and prisoner is explored as well as the possibility of personal freedom under repressive authority, and the effects of brutal institutionalisation. There is a remarkable range of emotions and motivations communicated through the visible machinations of desire – cruelty, domination, violence, defiance, as well as love and liberation.

Also revealed are the recurrent themes that unite Genet’s work and the cinematic techniques – of collage, flashback and close-up – which he adopted in his novels, plays and poetry.

Shot on 35mm by an established cameraman and professional crew, the cast was chosen by Genet from his circle of Montmartre associates and lovers. Originally intended for the eyes of only a few close friends, initially Genet and his circle were pleased with the film, but he later denounced it and refused the prize for ‘Best New Film’ of 1975 awarded by the Centre National de la Cinematographie.

Author Edmund White, in his preface to Criminal Desires: Jean Genet and Cinema by Jane Giles, comments: ‘His rejection of Un chant d’amour may have its roots in his fear that [unlike his first novel Our Lady of the Flowers] it was merely pornographic. Certainly by the time he denounced it definitively in the 1970s he had written several other film scripts, and his ideas about cinema as an art had evolved.’

Indeed, Genet was one of France’s maverick artists, a man who exchanged a life of extreme deprivation and degradation for that of a novelist, playwright and poet and became something of an existentialist hero to the likes of Jean Cocteau and Jean-Paul Sartre. Although greatly influenced by the medium of cinema, and writing many scripts later on in his career, Un chant d’amour is the only film he both wrote and directed. Long championed as one of the most emblematic films in gay cinema, it has unquestionably influenced generations of filmmakers, from the late Derek Jarman to Todd Haynes (his 1991 film Poison is directly inspired by Genet’s work).

The subject of ceaseless controversy and international censorship, Un chant d’amour was unseen for many years, becoming a cause célèbre of gay rights and freedom of expression, as well as being recognised as a masterpiece of underground cinema in its own right.

Heavily censored for many years and banned outright in the States until the late 70s on the grounds of obscenity, Un chant d’amour is not for the faint-hearted. The British Film Institute later released an uncut version of the original, which features footage of masturbation, sexual climax and homosexual acts. The BFI DVD release added a vibrant new music score by Simon Fisher Turner who was composer on Derek Jarman’s Caravaggio.

Looking at Genet’s film over 60 years on, it is clearly both captivating and moving, giving us a glimpse of a great poet at work with film – although, unfortunately, it’s the only glimpse there is.

US, 138 mins

Director: Joseph L Mankiewicz

Cast: Bette Davis, Gary Merrill, Anne Baxter, George Sanders, Celeste Holm, Thelma Ritter, Marilyn Monroe, Hugh Marlowe, Gregory Ratoff

Genre: Camp comedy-drama

Joseph L Mankiewicz’s jaundiced look at the showbiz battle zone better known as Broadway is probably the summit of Hollywood moviemaking.

Bette Davis gives the performance of her career portraying the just-turned-forty stage diva Margo Channing with a painful air of authenticity: the camp star, still awesome but aware of the ravages of time and the threat of younger actresses snapping at her heels. The actress is a living monument to enormous talent and volcanic temperament but what she needs is someone to follow her around, look after her and worship her, and that person seems to arrive in the form of Eve (Anne Baxter), an apparently innocent, adoring fan. But of course appearances can be deceptive. The younger woman is taken in as a kind of secretary and confidante to Margo but systematically sets about stealing her benefactor’s man and career. Margo begins to realise what’s happening but, through flattery and a series of double-crosses, Eve still manages to work her way to the top and cares little for Margo’s misfortune.

Eve was originally written as a lesbian character but all overt references to her sexuality were dropped. Nevertheless, to those in the know, the gay subtext was fairly obvious: it’s there in the voracious way in which Eve stalks Margo, through the subtle scene involving Eve’s roommate, and in the giveaway line delivered by Margo to her boyfriend, Bill Sampson, ‘Zanuck, Zanuck, Zanuck – what are you two, lovers?’ Finally, in case we missed the point, Eve falls for the same trick she had herself relied upon: on finding a young female fan who’s sneaked into her hotel room, she unwisely invites the girl to stay the night.

From left: Anne Baxter, Bette Davis, Marilyn Monroe, George Sanders

Mankiewicz triumphs as writer and director. What gives this cynical high comedy its emotional resonance and depth, however, is the poignance with which Davis plays Margo Channing. The piece, one of Hollywood’s finest backstage dramas, fizzes with energy and the bitchy lines flow, largely from Davis’s wickedly crooked mouth. The entire cast is on top form (Marilyn Monroe makes an early, fleeting cameo appearance), although among the actors only Sanders won an Oscar for his superb turn as the camp theatre critic, Addison DeWitt, who also serves as the film’s narrator.

Alongside the lesbian subtext, the film’s appeal amongst the gay community also lies in its star. Bette Davis, like Joan Crawford, was a true gay diva, a ‘bitch’ in every positive sense of the word. When Davis descended the stairs in All About Eve, regally gowned, her eyes burning with thoughts of vengeance, she was a portrait of strength. When she uttered that immortal line, ‘Fasten your seat belts, it’s going to be a bumpy night,’ she put into words the thoughts of every gay man who struggled to come out, or get laid with a not-so-safe stranger.

US, 115 mins

Director: Nicholas Ray

Cast: James Dean, Natalie Wood, Sal Mineo, Dennis Hopper

Genre: Youth drama

One of the most influential films ever made, Rebel Without a Cause is a timeless masterpiece. Kids of today can still relate to its basic premise: of youth misunderstood, of wanting to belong. The clothes, hair and times may have changed, but the story of three teenagers, bonding as the world around them seems to cave in, is just as potent now as it was in 1955.

In his most famous film, James Dean delivers a knockout performance, playing Jim Stark, the nervous, volatile, soulful teenager lost in a world that doesn’t understand him. It’s his first day at a new high school. The night before he is arrested for public intoxication. His dysfunctional parents don’t know how to handle the situation: Mum is overbearing and self-centred while lily-livered Dad has good intentions, but is constantly overruled by his wife. Jim needs guidance and begs for it, in his rebellion.

The film’s other teens in trouble include Judy (Natalie Wood) and John ‘Plato’, played to perfection by Sal Mineo (nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor). When we first meet Plato, he is being questioned over why he shot a bunch of puppies, a horrifying way to introduce a character, but somehow Mineo makes us care about Plato, a rich kid with tons of problems: his dad’s disappeared, and his mum’s always away, leaving him in the care of the family maid. Plato is looking for somebody to be his friend, or family. And by the end of twenty-four hours, these three will make their own tightly knit little circle.

Rebel is all about the basic need to feel loved. In Jim, Judy has found her perfect soulmate. Plato loves Jim too, but it’s a secret love and he’s constantly having to come to terms with his latent homosexuality. Plato would love Jim to stay overnight with him: ‘Hey, you wanna come home with me? ... If you wanna come, we could talk and then in the morning we could have breakfast...’

Made between his only other starring roles, in East of Eden and Giant, Rebel sums up the jangly, alienated image of Dean. He is heartbreaking, following the method-acting style of Marlon Brando but staking out a nakedly emotional honesty of his own. Dean is, of course, no longer an actor, but an icon, and Rebel is a lasting monument.

US, 122 mins

Director: Billy Wilder

Cast: Tony Curtis, Marilyn Monroe, Jack Lemmon, Joe E Brown, George Raft, Joan Shawlee, Mike Mazurki, Pat O’Brien

Genre: Comedy

Some Like It Hot is a cross-dressing comedy classic. Previously voted the best comedy film of all time by the American Film Institute, its campness and kinkiness has also made it a real favourite of gay audiences around the world.

Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon play two knockabout Chicago jazz musicians, Joe and Jerry, who happen to witness the Mob in bloodthirsty action during the infamous St Valentine’s Day massacre. Needing a quick getaway, the pair disguise themselves as ‘Josephine’ and ‘Daphne’, and join an all-female choir.

Director Billy Wilder puts a flawless cast through some riotous capers, as the all-girl band heads for sunny Florida. Star attraction Marilyn Monroe is wonderful as Sugar Kane, the sexy Polish-American vocalist in search of a rich husband. Joe, ever the ladies’ man, falls for the dazzling Sugar but is unable to reveal his true identity, so instead poses as a millionaire in an effort to woo the money-hungry singer. Jerry is also finding dilemmas of his own: lecherous millionaire Osgood Fielding (Joe E Brown) has his sights firmly set on Daphne/Jerry, which is okay so long as the gifts keep coming and the confused old horn dog is kept at a safe distance.

Tony Curtis (left) and Jack Lemmon drag up in Some Like it Hot

By the end of the movie Osgood has fallen so heavily for Lemmon’s Daphne persona, he takes ‘her’ out in a boat and proposes marriage. After failing to dissuade him, in desperation she exclaims: ‘Osgood you don’t understand… I’m a man!’ Unfazed, Osgood declares, ‘Nobody’s perfect!’

So if you thought that men-in-drag comedies had reached their pinnacle with Priscilla or Too Wong Foo, think again: this is a flawlessly scripted, superbly performed and endlessly witty comedy that deserves its place among the all-time greats.

US, 114 mins

Director: Joseph L Mankiewicz

Cast: Elizabeth Taylor, Katharine Hepburn, Montgomery Clift

Genre: Psychological drama

Suddenly, Last Summer is one of the big groundbreakers in gay cinema history. In 1959, the Motion Picture Production Code and the Catholic Church granted a special dispensation permitting the film to include the first male homosexual in American film. The word is never mentioned, the character did not speak and his face never appeared. His name was Sebastian Venable.

Gore Vidal’s classy but stark screen adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ powerful play not only landed Oscar nominations for stars Elizabeth Taylor and Katharine Hepburn (neither won), but also pulled off the trick of making Shepperton Studios near London look uncannily like New Orleans.

Set in 1937 New Orleans, Joseph L Manckiewicz’s film explores the trauma of Catherine Holly (Taylor), whose homosexual cousin dies an unspeakable and gradually revealed death while travelling with her in Europe. Katharine Hepburn as the murdered man’s wealthy mother, Violet Venable, can’t bear to hear the details of her son’s death, preferring instead to try and convince a doctor that he should have a lobotomy performed on her niece, insisting that the girl is mad. She thinks the lobotomy should remove the part of the brain which houses the memories of the day she witnessed Sebastian pursued and cannibalised by the hungry youths he had exploited. But Dr Cukrowicz (Montgomery Clift) is determined to explore the reasons behind the girl’s inexplicable actions and words, and eventually the young neurosurgeon uncovers the secrets the mother wants to hide. By utilising injections of Sodium Pentothal, he discovers that Catherine’s delusions are in fact true. He then must confront Violet about her own involvement in her son’s lurid death.

Williams’ play explicitly stated why the murdered man’s death so traumatised his cousin, but this adaptation written by Vidal, filled with wild, moody tension by director Joseph L Mankiewicz, allows viewers to read between the lines and form their own suspicions about Sebastian Venable’s death. Taylor is on top form, radiating uncertainty and fear as the girl terrorised by her cousin’s death and her fierce aunt’s obsession to keep her quiet. Hepburn gives a similar tour-de-force performance, swaying with menace in one of her few, deliciously played roles as a villainess.

A classic in every sense of the word, Suddenly, Last Summer touches on many subjects that were highly controversial at the time it was made, such as mental illness, homosexuality and cannibalism. Truth to be told, there’s a lot of inference and not much shown. The cannibalistic murder, for instance, is left to the viewer’s imagination, with the camera turning away as the street urchins destroy Sebastian. The inference only makes the film’s themes stand out even more.

Undoubtedly one of the most admired and adored gay icons, James Byron Dean’s impact on American youth culture is immense.

Born in Marion, Indiana, Dean began his career on the New York stage, and appeared in several episodes of such early-1950s episodic television progammes as Kraft Television Theater, Danger and General Electric Theater. After rave reviews in André Gide’s The Immoralist, Hollywood and film stardom called.

Dean appeared in several uncredited bit roles in such forgettable films as Sailor Beware, but finally gained recognition and success in 1955 in his first starring role, that of Cal Trask in East of Eden, for which he received an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor in a Leading Role. In rapid succession, he starred in Rebel Without a Cause, also in 1955, and in the 1956 Giant, alongside Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson, for which he was also nominated for an Academy Award. As Jett Rink, Dean once more played the brooding outsider, this time separated from his heart’s desire by his lowly station in life. Cast in a villainous light, Dean remained the most fascinating presence in the film, especially in his brilliantly choreographed, climactic drunk scene. In fact, Dean played the cast-off loner in all three of his starring features, unable to draw attention to himself until forcing the issue.

Even before Giant was released, Dean was a major celebrity and he began enjoying his money by entering the world of automobile racing. He purchased a Porsche 550 Spyder and on September 30, 1955, after completing work on Giant, he zoomed off to a racing event in Salinas. Travelling at 115 miles an hour, he was killed in a head-on collison just outside Paso Robles, California.

One of only five people to be nominated for Best Actor for his first feature role, and the only person to be nominated twice after his death, Dean epitomised the rebellion of 1950s teens, especially in his role in Rebel Without a Cause. Many teenagers of the time modelled themselves after him, and his death cast a pall on many members of his generation. His very brief career, violent death and highly publicised funeral transformed James Dean into a cult object of timeless fascination. A life that’s achieved mythic proportions, Dean’s sexuality has also become a topic of endless fascination.

So was James Dean gay? Years after his death, in various biographies, writers and Hollywood insiders outed the original rebel actor. In Paul Alexander’s biography, Boulevard of Broken Dreams, the author revealed publicly what many have acknowledged privately – that Dean’s so-called ‘sexual experimentation’ was a convenient Hollywood euphemism for his lifelong attraction to men. In fact, later on, Dean became fascinated by sadomasochism, with studio make-up artists having to cover up the cigarette burns inflicted by his lovers.

When Dean moved to New York to pursue his acting career, many claim it was advanced when he became sexually involved with an ad man/director who introduced him to influential people in the city. Dean began dating a male producer who later cast him in See the Jaguar on Broadway.

The love of Dean’s life, however, was allegedly his former flatmate William Blast and their relationship was documented in the 1976 TV movie James Dean, which dealt fairly explicitly with Dean’s homosexuality.

Dean had also developed close relationships with actors such as Clifton Webb, Arthur Kennedy and Martin Landau and later was introduced to the young actor Nick Adams. While Dean was filming East of Eden, Adams was making Mister Roberts the same year. They became very close, with Adams making himself available for whatever services were required of him. In fact Adams was yet another actor who met an untimely death, dying of an overdose at 37 in 1968.

Despite his very short career in acting, James Dean has become a major figure in American culture. This most enigmatic of actors was a shy, deeply insecure man who never recovered from the early loss of his mother. Charismatic, ambitious and astoundingly gifted, he was also notoriously moody and difficult, his desperate need for affection and attention often manifesting itself in contradictory, ultimately self-destructive behaviour.

His deep and complex personality has intrigued all who have seen his performances, making everyone wonder how different the world would be if he had lived on to produce more great films.

Judy Garland remains the ultimate gay icon – the original diva who sparkled on screen long before Streisand, Cher and Madonna. Born Frances Gumm in 1922, she entered the public eye in 1939 as Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, and sang her way through more than 30 films and dozens of stage appearances.

Her performance in Oz won her a special Juvenile Oscar, and it was this role, of course, that gave Garland her most famous song, ‘Over the Rainbow’. It was also the film that resonated throughout the gay community. Dorothy was the misunderstood kid from a small town who has an amazing adventure in a Technicolor world. Despite intense fear, confusion and a series of trials, she finally makes it ‘home’ by realising that she possessed all of the heart, strength and courage needed to find the true happiness that lived within. That message resonated with gays of the era who yearned to come out into a colourful world and live what was inside them.

After Oz, Garland appeared in a string of classic MGM musicals, including Meet Me in St Louis (1944), Easter Parade (1948) and several with her friend, Mickey Rooney. Unfortunately, the same studio that made her a star unwittingly made her a drug addict, providing her with amphetamines to keep her energy levels high and her weight down. This kept her wide awake at night, so she was given barbiturates to help her sleep, and soon she couldn’t live without these ‘wonder drugs’. She also couldn’t seem to live without a man, going through several affairs, often with older men, and by 1950 had been married twice, to bandleader David Rose and director Vincente Minnelli, with whom she had a daughter, Liza Minnelli. During this time her drug intake increased dramatically, and led to increasingly erratic behaviour. She often failed to show up on time at the studio and MGM eventually couldn’t take it any more, terminating her contract in 1950.

Garland divorced Minnelli the following year and married producer Sidney Luft, father of her daughter Lorna and son Joey, who took it upon himself to orchestrate her comeback with a series of extremely successful concert tours. He also produced the film A Star is Born (1954), in which many feel she gave her greatest performance.

At her best, Garland gave everything to her audience. As ‘the little girl with the grown-up voice’, she often trembled, her strong vibrato sending shivers through her fragile frame. But her worst troubles – the drugs, the suicide attempts, failed marriages and breakdowns – seemed to draw the most die-hard fans. She was one of the first stars to show her bruised life to her public, and gay men felt her pain. Her songs of love, anguish and sacrifice touched a nerve with an invisible generation which identified with the dichotomy of her life; they too had to hide behind walls of perceived strength, all the time hoping that, somewhere over the rainbow, they would overcome their troubles.

Garland’s true connection with gay men was rooted in her ability to overcome the inner conflict, instability and loneliness that defined her life even during stardom. She sang of intense loneliness and of delirious love, maintaining a ‘stage presence’ at all times despite her inner turmoil.

In the 1950s, Garland’s concerts were major gay meeting places, and in her later years, she even made money singing at gay piano bars, performing to men who used the term ‘friend of Dorothy’ to refer to themselves in mixed company, in homage to Garland’s character in The Wizard of Oz.

After her successful early-50s comeback, Garland concentrated on her career as a singer, winning legions of fans. She continued touring throughout the 1950s and 1960s, appearing in three more films and starring in her own television variety show in 1963. The show, however, had to be cancelled after one season because the competition, Bonanza (1959), was too strong. She divorced Luft and married actor Mark Herron, who she divorced when she found out he was gay, and married disco manager Mickey Deans. She continued to depend on prescription drugs, and finally the inevitable happened: on the night of 22 June 1969, she overdosed on barbiturates and died. Thousands mourned the world over. It was a sad way to end, but she left a great legacy: her many films and recordings, as well as her children, Liza and Lorna.

An emotional icon, the death of Miss Showbusiness in 1969 was considered by many to be a contributing factor that helped spark the Stonewall Riots, which took place over the same weekend in New York. This, in turn, launched the militant gay rights movement.

In the late 1950s, Sal Mineo was one of the hottest movie stars in the world. Twice nominated for an Academy Award, Mineo’s career spans three decades, although he will always be fondly remembered for his role opposite James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955).

Mineo earned his acting stripes on Broadway, appearing first in The Rose Tattoo (1951) and then in The King and I (1952), taking over the role of Yul Brynner’s son. He effortlessly made the transition to the screen, appearing in Six Bridges to Cross and The Private War of Major Benson (both 1955) before earning celluloid immortality in the teen-angst classic Rebel Without a Cause as Plato, a tender portrayal which earned a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award nomination.

Mineo went on to play variations of the juvenile delinquent role in such films as Crime in the Streets (1956), Dino (1957), and The Young Don’t Cry (1957). He was also nominated for Best Supporting Actor for his role in this movie and again for the role of Dov Landau in Exodus (1960). But in the 60s, after he started becoming more open about his sexuality, he found that fewer good parts were offered to him; he commented: ‘Suddenly it dawned on me I was on the industry’s weirdo list.’

He subsequently left Hollywood and began working all over Europe, where he was offered more interesting roles. He also found success on stage back in the States, as director of Fortune and Men’s Eyes and co-star of P.S. Your Cat is Dead!, playing a bisexual cat burglar.

Discussing his sexuality, Mineo said, ‘I like them all – men, I mean. And a few chicks now and then.’ Unlike James Dean, Montgomery Clift, Rock Hudson et al, he seemed quite happy being out of the Hollywood closet. He once said: ‘One time, when my Ma wondered how come I turned out gay, I asked her, “Ma, how come my brothers DIDN’T?”’

Preparing to open the play P.S. Your Cat is Dead! in Los Angeles in 1976 with Keir Dullea, he returned home from rehearsal the evening of 12 February where he was attacked and stabbed to death by a stranger. In 1979, Lionel Ray Williams was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for the murder.

It’s sad that his life had to end at the early age of 37, but the memory of Sal Mineo continues to live on through the large body of TV and film work that he left behind.