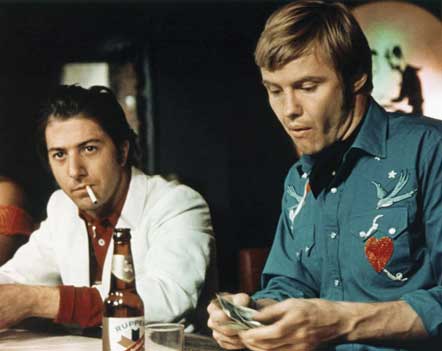

Jon Voight (left) and Dustin Hoffman in John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969), the only x-rated movie ever to win an Oscar © Photofest

Jon Voight (left) and Dustin Hoffman in John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969), the only x-rated movie ever to win an Oscar © Photofest

Before the rise of independent cinema, it seemed that up to and throughout the 60s, gay and lesbian characters were portrayed as either villains to be feared, or tortured, suicidal individuals to be pitied.

For most of the decade, few of these characters of ‘questionable sexuality’ survived the final reel.

‘If you’re old enough to vote, you’re old enough to choose your own way of life.’

Galloway in Victim

They were presumably paying rent and taxes, earning a wage and buying their groceries just like everyone else, but what the films told us was that homosexuality often led to Misery, Death, and The Destruction of Society As We Know It!

In 1961, Tony Richardson’s acclaimed film A Taste of Honey had Rita Tushingham setting up house with an optimistic young gay guy she picks up at a carnival. Geoff, played by Murray Melvin, was one of cinema’s first gay anti-heroes. Tushingham treats her effeminate homosexual friend as a sister, but Geoff, because of his sexuality, is seen as marginal to mainstream society. Significantly, on its initial release, A Taste of Honey was supplemented by a study guide, reprinted in Life magazine, on the ‘causes and cures’ of homosexuality.

In Brian Forbes’ The L-Shaped Room (1962), based on the novel by Lynn Reid Banks, Leslie Caron starred as a pregnant, unmarried French girl who moves into a seedy London lodging house that’s home to a variety of sympathetically observed but ultimately marginal inhabitants, including a homosexual black trumpeter called Johnny (Brock Peters) and an elderly lesbian music-hall artist (Cicely Courtneidge). Like the sexless Geoff in A Taste of Honey, Johnny in The L-Shaped Room is peripheral, although his understated affection for another male lodger is sympathetic and handled well, and he is in no way threatening.

The Leather Boys (1964), directed by Sidney J Furie, was another example of how filmmakers handled the gay lifestyle. Implied homoerotic tensions between two pals, Reggie (Colin Campbell) and Pete (Dudley Sutton), come to the surface when Reggie marries Dot (Rita Tushingham) but soon loses his sexual urge and opts to move in with his ‘buddy’ Pete. Despite Pete’s insistent affection, his reluctance to associate with girls and his housekeeping ability, Reggie fails to wise up to the fact he’s a homosexual. The plot is punctured somewhat by the fact that most viewers get the drift early on, and when Reggie realises that Pete really is ‘queer’ and rejects him, it becomes yet another example of a director who balks at a happy gay ending.

Throughout the 60s, more gay characters appeared, but despite the liberation of young men, cinema was not yet ready to liberate gays.

‘I’m not a lifebelt for you to cling to. I’m a woman and I want to be loved for myself.’

Laura in Victim

The ‘pathology’ of homosexuality, largely the result of the medical establishment’s negative attitude, became rife in cinema with crazy queers appearing in such films as Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967) and The Sergeant (1968). It’s interesting that both these films are set in a military environment, the implication being that such all-male environments are in danger of breeding homosexuality, which in turn creates murderous tendencies.

If they weren’t villainous, they were suicidal. In Sidney Lumet’s A View From The Bridge (1962), Raf Vallone implicates his own sexuality by accusing another man of being gay; eventually he too kills himself. Meanwhile, Advise and Consent (1962), produced and directed by Otto Preminger, features a scene set in a gay bar; also a suicide, which occurs when politician Don Murray is blackmailed for a past gay fling. In The Children’s Hour (1961), the accusation of lesbianism (not entirely unfounded) ends with a rope suicide; and in The Sergeant, the title character kills himself after kissing a private.

‘I wanted him! I wanted him, as a man wants a girl!’

Melville Farr in Victim

Interestingly, while their gay characters paid the obligatory price by committing suicide, the stars of The Children’s Hour (Shirley MacLaine), The Sergeant (Rod Steiger) and Reflections in a Golden Eye (Marlon Brando) all managed to survive the career threat of a gay role, as did two of Hollywood’s most notorious heterosexuals, Richard Burton and Rex Harrison, who starred as a long-time gay couple in Staircase (1969).

As well as victims and villains, 1960s gay cinema was also full of sissies, characters who made their presence felt in a kind of leering, sniggering way. In the Rock Hudson vehicles Lover Come Back (1961) and A Very Special Favor (1965), the actor pretends to be a sissy in order to win over a girl, the irony of which isn’t lost now that we know of Hudson’s sexuality.

DETECTIVE INSPECTOR HARRIS:

‘Someone once called this law against homosexuality the blackmailer’s charter.’

MELVILLE FARR:

‘Is that how you feel about it?’

DETECTIVE INSPECTOR HARRIS:

‘I’m a policeman, sir. I don’t have feelings.’

from Victim

In British movies, Kenneth Williams and Charles Hawtrey’s Carry On characters were two of the most popular of the series’ gang. But they weren’t gay, of course – they were sissies. Their limp hand gestures and airy-fairy ‘ooh-I-say’ tones put the representation of gay characters right back to the era of silent movies; and even by the late 60s, in the era of sexual freedom, many films still featured pitiable homosexuals who do everything for others but neither expect nor get happiness for themselves. It’s an all too familiar notion that gays seem most loveable (or non-threatening) when rendered essentially sexless. And that’s what these characters were – funny quirky, sexless people. Kenneth Williams’ own highly personal diaries, published after his death, revealed his growing hatred of the stereotypical fairy types he was lumbered with, which not only typecast him but added to his own real-life personal insecurities.

But in one British movie, a character uttered the word ‘homosexual’ for the first time – and it wasn’t a laughing matter. It was Victim (1961) that put down a marker for the serious consideration of homosexuality at a time when being outed could lead to a prison sentence. The film featured Dirk Bogarde, who broke free from his matinee idol image to play a gay barrister who’s blackmailed by a young man who then commits suicide. When he tracks down a range of men who have been similarly compromised, he is faced with the choice of coming out or keeping silent. He opts for the latter.

Victim was extraordinary for two scenes. In one, the barrister explains to his wife the ins and outs of gay desire (‘...and I wanted him! I wanted him, as a man wants a girl!’); and in the other a gentlemen’s club is full of posh homosexuals who drink sherry and speak in very English clipped tones about ‘our sort’. In insisting that there were a lot of them around, however, the film did a service to the gay community – despite the fact that the director, Basil Dearden, referred to gays as ‘sexual inverts’.

Still, it’s impossible to underestimate the importance of Dearden’s film, however polite and quaint it feels today. It proved to be a major factor in the decriminalisation of homosexuality.

In September 1961, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America announced a revision of its Production Code: ‘In keeping with the culture, the mores and the values of our time,’ the revision advised, ‘homosexuality and other sexual aberrations may now be treated with care, discretion and restraint.’ Changes in the acceptable images of Hollywood films reflected mainstream Americans’ limited willingness to view homosexuality in the mass media. Homosexuality could be portrayed and discussed as long as the images and discussions were ‘safe’ and ‘discrete’.

‘I’ve been telling myself that since the night I heard the child say it. I lie in bed night after night praying that it isn’t true. But I know about it now. It’s there.’

Martha in The Children’s Hour

The new Production Code revisions paved the way for the release of films like The Children’s Hour (1961), an adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s 1934 play that made it to the screen with its lesbian content intact as an example of a ‘tasteful’ treatment of homosexuality. The film had Shirley MacLaine committing suicide after she realises that lesbian rumours about herself are true – another example of a homosexual character not making it to the end without dying – but it did represent the first major release in the United States to deal clearly with lesbianism.

The Children’s Hour also cleared a path for lesbian subplots in the mid-60s. Shelley Winters was a madam with a yen for Lee Grant in The Balcony (1963), Joseph Strick’s film of the Jean Genet play. Jean Seberg’s mental patient is openly bisexual in Robert Rossen’s Lilith (1964) and Candice Bergen is the nice college girl who’s also ‘sapphic’ in Lumet’s The Group (1966).

The premiere of The Group marked the first time the word ‘lesbian’ was actually used in a Hollywood movie: when the film’s central character, Lakey (Candice Bergen), returns from Europe with a butch baroness as her lover, Larry Hagman turns to her and says, ‘I never pegged you as a Sapphie – to put it crudely, a lesbo.’

Radley Metzger’s

Therese and Isabelle (1968)

Another ‘shocking’ lesbian-themed film of this period came from Germany. Therese and Isabelle (1968) was a kind of lavish soft-core fantasy film about women who were in love with each other, notable more for its lush, lyrical photography and fabulous design than for its acts of passion. It is still well known, however, and appears on special edition DVD formats around the world, released for fans of films produced during the dreamy era of porno chic.

By the mid-60s, a vibrant underground film scene was burgeoning in New York’s East Village with a large network of artists, writers, filmmakers and hangers-on. In 1963 alone, three of the most notoriously ‘queer’ avant-garde films of this period were produced: Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising, Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures and Barbara Rubin’s Christmas on Earth.

And, as the 60s sexual revolution took hold, the avant-garde artist Andy Warhol was turning out a dizzying number and variety of films involving a host of different collaborators. Working in close collaboration with his protégé Paul Morrissey, the films were made in an East 47th Street studio dubbed ‘The Factory’, where Warhol developed his own star system. His performers included drag queens Holly Woodlawn and Candy Darling, women such as Bridget Polk and Edie Sedgwick, and hustlers Paul America and Joe Dallesandro. Films like Blow Job (1963), My Hustler (1965) and Lonesome Cowboys (1968) drew from the gay underground culture and openly explored the complexity of sexuality and desire. Indeed, Blow Job was basically a 35-minute close-up of a young man’s face as he receives oral sex. Not surprisingly, many of Warhol’s films premiered in gay porn theatres.

Lonesome Cowboys (1968)

Warhol described My Hustler in simple terms: ‘It was shot by me, and Charles Wein directed the actors while we were shooting. It’s about an ageing queen trying to hold on to a young hustler and his two rivals, another hustler and a girl; the actors were doing what they did in real life; they followed their own professions on the screen.’

Some critics hold his films in high esteem and many cite My Hustler as a classic of gay cinema. Others dismiss it as pointless and boring. But what is so frustrating is that it’s impossible to assess most claims made about these films: controlled by his estate, they have not been made available for video or DVD release.

Warhol’s contribution to gay cinema was immense, and it’s a tragedy that his works are so little known today. In fact, many of his earlier short films have been lost or destroyed. Warhol, Smith and Anger’s titles are now widely regarded as some of the most important and influential films of post-war underground cinema. Only recently, however, have critics begun to take seriously the fact that they were gay filmmakers whose films developed a distinctly queer aesthetic.

As Warhol was completing his most famous film, The Chelsea Girls, at the end of 1966, after 37 years of self-imposed censorship, the Production Code finally came down forever, giving new licence to Hollywood films.

In 1967, Sandy Dennis and Anne Heywood were cast as lesbian lovers in The Fox, a sensitive dramatisation of DH Lawrence’s novella; and in The Detective, Frank Sinatra was playing a tolerant New York City cop investigating a messy murder of a young homosexual.

In Italy, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (1968) was causing controversy. Long before he was dragging up for Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, Terence Stamp played a divine stranger who insinuates himself into the sumptuous residence of an upper-class industrialist. One after another, he seduces the mother, the father, son, daughter and maid. Soon a telegraph arrives at the dinner table, and the stranger tells the family he must leave immediately. Their safe middle-class world having been screwed over, the family members now experience epiphanies of self-awareness, admitting to the stranger that he has awakened them to the shallowness of their lives. After he leaves, each of the family members immediately deviates from the status quo.

With its frequent homosexuality, Pasolini’s film was designed to disturb its audience. Despite winning the Grand Prix at the Venice Film Festival in 1968, Teorema was publicly denounced by Pope Paul VI and banned as obscene in Italy. Pasolini was even arrested, but, in a much-publicised trial, acquitted of all charges. While it has certainly lost some of its subversive power over the last 40 years, it remains Pasolini’s finest Marxist slap in the face to his hated bourgeoisie.

ALICE:

‘Not all women are raving bloody lesbians, you know.’

GEORGE:

‘That is a misfortune I am perfectly well aware of!’

from The Killing of Sister George

Back in Britain, one film that dealt intelligently and sympathetically with homosexuality was The Killing of Sister George (1968), a great breakthrough movie of the 60s, which marked a change of attitude from the public. The story of an ageing lesbian who loses her TV job and young lover was funny and entertaining from beginning to end but also dealt with homosexuality not as a problem or stigma but as part of the natural order.

Despite the demise of the Production Code, Hollywood didn’t immediately put a stop to gay stereotypes. Producers continued to have gay and transgendered characters as the butt of all the jokes in comedies such as The Producers (1968) and Candy (1968). Meanwhile, Richard Burton and Rex Harrison were paired up to play two ageing homosexual hairdressers in Staircase (1969), but their characters seethed with guilt, shame, regret and self-loathing. To top it all, both wish they were straight!

In the same year, The Gay Deceivers was released, complete with the most flagrant gay stereotypes this side of Fairyland. A story of two young men (Lawrence Casey and Kevin Coughlin) who avoid the Vietnam draft by posing as gay lovers, the pair move into a gay apartment complex, with a bright pink bedroom, and a mincing, limp-wristed landlord (Michael Greer).

‘Uh, well, sir, I ain’t a f’real cowboy. But I am one helluva stud!’

Joe Buck in Midnight Cowboy

‘John Wayne! Are you tryin’ to tell me he’s a fag?’

Joe Buck in Midnight Cowboy

Variety reported that disgruntled gay cinemagoers were picketing The Gay Deceivers in San Francisco and quoted one protestor as saying: ‘The producers of such rot [should] take note that this film is not only an insult to the proud and “manly” gay persons of this community but to the millions of homosexuals who conceal their identity to fight bravely and die proudly for their country which rejects them.’ Many critics agreed, denouncing Deceivers as ‘witless’ and a ‘travesty’.

The end of the Production Code did, however, result in one of the most impressive films of the decade – Midnight Cowboy – which won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1969, the only X-rated movie to ever do so.

Directed by John Schlesinger, it was the first gay-themed Best Picture-winner in Oscar history, 35 years before Ang Lee’s gay cowboys graced the silver screen. Of course, Midnight Cowboy could never have been as explicit, or as tolerant, as Brokeback Mountain (2005), but it caused quite a stir on its release.

Waldo Salt’s screenplay – about a male hustler (Jon Voight) and his buddy (Dustin Hoffman) – did everything it could to avoid acknowledging the true heart of its narrative: that of two deeply lonely men who find a measure of grace in one another. Ultimately, their relationship was left as an ‘are-they-or-aren’t-they?’ affair.

Schlesinger’s film premiered in New York one month before the 1969 Stonewall riots that would mark the beginning of the gay rights movement.

UK, 90 mins

Director: Basil Dearden

Writers:Janet Green, John McCormick.

Cast: Dirk Bogarde, Sylvia Syms, Dennis Price, Anthony Nicolls, Peter McEnery, Derren Nesbitt

Genre: Thriller

‘While we were filming, we were treated as though we were attacking the Bible… yet it was the first film in which a man said “I love you” to another man. I wrote that scene in. I said to them, “Either we make a film about queers or we don’t.”’

– Dirk Bogarde on Victim

Victim is the groundbreaking thriller that paved the way for the legalisation of homosexuality in Britain.

Writers Janet Green and John McCormick, producer Michael Relph and director Basil Dearden were the team that produced Sapphire, involving racial prejudice, and they adopted a similar technique with Victim. They provided a suspenseful thriller that followed a group of blackmailers targeting London’s gay community, and at the same time argued a convincing case for gay rights and dignity, without resorting to unbalanced and contrived characterisations.

During a time when homosexual acts in private were illegal in the United Kingdom (as they still are in thirteen US states), Britain’s most revered matinee idol, Dirk Bogarde, risked his career to portray Melville Farr, a closeted gay lawyer. The film was released in Britain in 1961, halfway between the Wolfenden Commission’s recommendation of law reform in 1957 and the actual 1967 law reform.

In the opening scene of Dearden’s film, a handsome, edgy-looking young man called Barrett is at a construction site. He looks down from a steel girder high above the ground to see a police car arriving. He flees in desperation. But he is not being chased by police who want to arrest him because he is gay; as we later find out, Barrett is actually embezzling money from the construction company to pay blackmailers. Barrett (lovingly called ‘Boy Barrett’ in the queer underground), however, is protecting a much bigger target, wealthy barrister Melville Farr (Bogarde), with whom he is in love. Farr is married and a non-practising homosexual, who is about to ‘take the silk’ (become a Queen’s Counsel). He interprets Barrett’s desperate phone calls as blackmail attempts, inadvertently triggering the young man’s suicide in a jail cell.

Dirk Bogarde as blackmailed lawyer Melville Farr with Sylvia Syms as his wife Laura in Basil Dearden’s ground breaker

As the blackmailers turn their attention to Farr himself, he must decide whether to expose them and ruin his career (and possibly his marriage) in the process, or continue to pay extortion ‘for a kind of security’ that he knows will keep the whole rotten system going.

Bogarde’s portrayal of the increasingly beleaguered barrister is not only a knockout performance in itself but represented a major shift for the actor, who took the role after it was turned down by most of Britain’s major stars because it was too controversial. Sylvia Syms, meanwhile, provides solid support as Laura, his equally stressed wife. She shines in her portrayal of a woman torn between her love for her husband and the realisation of the social implications of his homosexuality being made public.

In his memoirs, Bogarde said that Victim was ‘the wisest decision I ever made in my cinematic life. The fanatics who had been sending me four thousand letters a week stopped overnight’. It was certainly a courageous move for the actor, then enormously popular for playing war heroes and heartthrobs, notably in the Doctor in the House comedies. After Victim, Bogarde’s main fan base withered but he was taken far more seriously as a dramatic actor, and more extraordinary work followed – The Servant, Accident, Darling, Death in Venice and The Night Porter.

Victim was reviled in its day, and many crew members apparently worked throughout on set with obvious contempt. The film could not get a MPAA seal for American distribution, mainly because of the mention of the then-forbidden word ‘homosexual’ (though, as Vito Russo pointed out in The Celluloid Closet, the MPAA had just allowed the word ‘faggotty’ from the mouth of Sidney Poitier in Raisin in the Sun), and because ‘sexual aberration could be suggested but not spelled out’.

In the week of release, TIME’s film critic was horrified: ‘What seems at first an attack on extortion seems at last a coyly sensational exploitation of homosexuality as a theme – and, what’s more offensive, an implicit approval of homosexuality as a practice.’

It is now clear that Victim was pioneering in its treatment of a long-repressed ‘crime’ and admirable for its sympathetic and non-stereotypical depictions of gay men. In Dearden’s film, homosexuals are not caricatures but multi-layered human beings. Homosexuality is normalised (rather than glamorised), shown at every level of contemporary society – in every side street, factory, Rolls Royce and club in town.

On the British DVD, recently released, one of the extras – a half-hour interview with Bogarde shot soon after Victim – amusingly shows a journalist trying to taunt the actor with questions and comments: ‘You must feel very strongly on this subject to risk losing possibly a large part of your following by appearing in such a bitterly controversial part.’ But then, perhaps the interviewer knew what most people at the time did not, that Bogarde was in fact gay himself, a fact which surely contributed to his perfect performance as Melville Farr, complete with its nuances of guilt and terror. Ironically, unlike his character, he was never completely open about his private life (he lived with his longtime companion Tony Forwood). Yet, during the interview Bogarde is completely relaxed.

Today this black-and-white movie is still an entertaining drama, bolstered by strong performances and great attention to detail. But the real importance of Victim will always lie in its role in the eventual decriminalisation (in part) of homosexual acts between men of 21 years or over in England and Wales, through the Sexual Offences Act of 1967.

US, 109 mins

Director: William Wyler

Writer: John Michael Hayes

Cast: Audrey Hepburn, Shirley MacLaine, James Garner, Miriam Hopkins, Fay Bainter, Karen Balkin

The Children’s Hour was the first major film released in the United States to deal clearly with lesbianism. Lillian Hellman’s study of the devastating effect of malicious slander and implied guilt had already been brought to the screen once before in a film called These Three back in 1936 but had veered away from the touchier, more sensational aspects of Hellman’s Broadway play. This time, however, director William Wyler chose to remain faithful to the original source.

The nature of the depiction of lesbianism in this film reflects the type of images that were considered tasteful to American audiences in the early 1960s. Hollywood was ready to release a film with lesbian content as long as lesbianism was treated as an unhealthy condition with no opportunity for happiness.

Shirley MacLaine and Audrey Hepburn co-star as headmistresses of a boarding school for young girls from wealthy families. After an irresponsible, neurotic child whispers to her grandmother a lie about a sexual relationship between the two women, the accusation spreads and the school is destroyed as parents remove their children.

The film is meant to illustrate how lies have the power to destroy the lives of innocent people; however, the movie takes an interesting turn as MacLaine’s character, Martha Dobie, realises there may be some basis for the child’s lie. Martha is forced to confront her own feelings for her friend Karen (Hepburn) and in an emotional scene she reveals her true feelings. In a speech filled with torment and self-hatred, she cries, ‘I’m guilty! I’ve ruined your life and I’ve ruined my own. I feel so damn sick and dirty, I just can’t stand it anymore.’ The words ‘lesbian’ and ‘homosexuality’ are never used in the film but the implications are clear. Martha explains to Karen, ‘There’s something in you, and you don’t know anything about it because you don’t know it’s there. I couldn’t call it by name before, but I know now. It’s there. It’s always been there ever since I first knew you.’

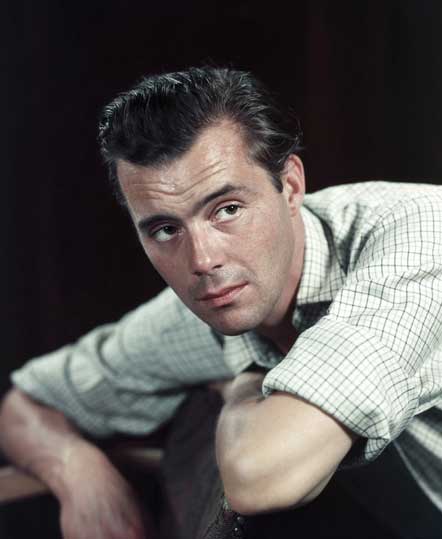

French-born director William Wyler with Audrey Hepburn on the set of The Children’s Hour (1961)

Around the time of making his film, director William Wyler stated: ‘It’s going to be a clean picture with a highly moral story.’ And so Martha’s self-realisation leads to her suicide. The little girl’s lie revealed a truth that was so unacceptable to her that she chose death as the solution to her struggle with her lesbian feelings.

Admittedly, the stars of The Children’s Hour made risky, admirable choices in their career by taking these roles on, rescuing the picture from box-office failure, but although the issue of invisibility was overcome, the increasing visibility of lesbians was now accompanied by portrayals of violent, predatory, overt or lonely homosexuals. The Children’s Hour represents a typical characterisation in which lesbianism has to be seen as a hopeless lifestyle, which inevitably leads to destruction. Filmmakers could not have characters accepting or embracing their homosexual feelings and desires because the film industry would then be seen to be glamorising or encouraging homosexuality. The repressed, tortured homosexual character, therefore, has no choice but to commit suicide because, as films such as The Children’s Hour suggest, it is the only viable option to dealing with such unacceptable sexual desires.

US, 109 mins

Director: John Huston

Writers: Chapman Mortimer, Gladys Hill

Cast: Elizabeth Taylor, Marlon Brando, Brian Keith, Julie Harris, Robert Forster, Zorro David

Genre: Military drama

John Huston turned Carson McCullers’ novel about a latent homosexual US army officer into quite an interesting melodrama. Set in the pre-Second World War period, Huston’s film features a veritable hothouse of repressed desires and fantasies, and six disparate characters: moody Marlon Brando’s brooding latent homo; his wife Elizabeth Taylor, who’s playing away with another officer; Brian Keith, whose own wife, Julie Harris, is having an affair with her houseboy, Zorro David; and finally Robert Forster, a young exhibitionist who Brando falls for.

Stuck in the married quarters of a Deep South army base, Taylor and Brando’s marriage has seriously hit the rocks and they spend most of their time shouting and screaming at each other. One fight ends with Taylor completely disrobing and threatening Brando with being ‘dragged out in the street and thrashed by a naked woman’, causing Brando to yell out ‘I hate you!’, as the handsome young private (Forster) lurks outside watching.

Next door, unhappily married couple number two are just as frustrated. Julie Harris is still traumatised from the death of their infant daughter, whereupon she mutilated herself. As Taylor helpfully explains, ‘I can’t imagine. Cuttin’ off your own nipples!’, to which Harris’s hubby Brian Keith replies, ‘Well, the doctors said she was neurotic.’ Harris ends up playing around with her Filipino houseboy Anacleto (Zorro David), and eventually Keith decides Harris needs to be committed and promptly drops her off at the local sanatorium.

While Taylor carries on her affair with Keith, Brando hopefully dogs the virginal young Forster, who’s got a penchant for riding naked in the woods. At various junctures, in an attempt to fill the empty hours, he takes to his study so he can look at various mementos, which include photographs of gladiators and a tiny, antique-silver teaspoon. Later he obtains Forster’s discarded Babe Ruth candy-wrapper, which he folds into a phallic shape and strokes. But however much he wants Forster, being the military man he is, he is forced to repress everything.

The soldier meanwhile takes to sneaking into Taylor’s room to watch her sleep, and the film predictably ends in murder. As Forster breaks in, Brando barges into Taylor’s bedroom to find him sniffing a nightgown, and shoots him dead.

It’s not as muddled or pretentious as it sounds, and Huston’s quirkish sense of humour is way ahead of other directors of the time. The script manages to lend genuine depth and credibility to the characters, far better than the other military-themed gay-interest movie of that time, The Sergeant (1968), a badly written tale of self-loathing.

Reflections in a Golden Eye captures the sheer frustration of it all – the boring lectures on military history, being stuck in classrooms during a hot summer, and the late-night drinks and card games which are more an effort to ease loneliness. All in all, it’s a superbly controlled exercise in the malevolent torments of despair.

Interestingly, Brando developed his status as a gay icon not just through his early, stunning good looks and fantastic physique. His private life was dogged with rumours of gay affairs, most of which he didn’t bother to deny, which only helped to secure an army of adoring gay fans. He lived in New York with his lifelong pal, actor Wally Cox, and did not contradict rumours that they were lovers. He even admitted: ‘Like many men I have had homosexual experiences and I’m not ashamed.’

US, 138 mins

Director: Robert Aldrich

Writer: Lukas Heller

Cast: Beryl Reid, Susannah York, Coral Browne, Ronald Fraser, Patricia Medina, Hugh Paddick, Cyril Delevanti

Genre: Lesbian-interest black comedy

One of the great and infamous lesbian ‘breakthrough’ films of the 60s, Robert Aldrich’s film concerns an ageing lesbian actress called June Buckeridge (Beryl Reid) who’s the star of the hugely popular television soap opera Applehurst. Buckeridge has become so identified with her character – a sweet-natured district nurse called Sister George, who putters around her pretty little village on a motor scooter – that she’s even known as George away from the set.

Outside the studio, however, she’s an aggressive, hard-drinking, hot-tempered, cigar-chomping, foul-mouthed lesbian living with an immature young lover she’s nicknamed ‘Childie’ (Susannah York).

George’s domineering personality and self-destructive tendencies have placed her starring role in jeopardy, and she feels certain that ‘Sister George’ will soon be killed off. She vents her frustration on her lover and at one point even demands that Childie eats one of her cigars until she chokes and vomits from revulsion. Tired of being punished for breaking George’s rules, she loses interest in the relationship and the soap star’s world starts to fall apart.

On one of her drunken sprees, George goes too far and is accused of molesting two young nuns in a taxicab with behaviour so outrageous that one of them ‘went into shock believing she was the victim of satanic intervention’. BBC executive Mercy Croft (Coral Browne) drops in on George at home and demands that she write a sincere letter of apology to the Director of Religious Broadcasting. Mercy also makes several subtle passes at Childie, which don’t go unnoticed by George.

Tension builds as Mercy takes control of George’s television career and her love life. Soon George is told by Mercy that she will be written out of the show: ‘She’ll be hit by a truck while riding her scooter – and the episode will nicely coincide with advertisements for Automobile Safety Week!'

Adding insult to injury, Mercy also advises George that she can still have a job: ‘We do have an opening on one of our children’s shows. You can play Clarabelle the Cow. All you have to do is wear a mask and say, “Moo!” – That’s if you choose to accept the role.’

In the heartbreaking final moments, George returns to the empty set of her beloved TV show. On the dimly lit set, she finds the coffin destined for her character and begins to smash it – and the set – to pieces. As the camera tracks back to a long shot from above, George lets out a long, heart-wrenching ‘moo’, bringing down the curtain on a genuinely moving scene.

The performances in The Killing of Sister George are exceptional and Beryl Reid’s magnetic performance really should have earned her an Oscar nomination. Producers took a chance on Reid – known mainly for her comedy roles – by casting her in the original Broadway play, and she rewarded their gamble, winning the Tony Award for Best Actress. Despite reservations by Hollywood moneymen, Aldrich took another gamble and allowed Reid to recreate her role for the screen. The gamble paid off. Touching on many emotions, Reid creates a real human being who’s easy to empathise with.

Because of its lesbian love scene, Sister George received an X rating, which limited its exposure in theatres. Aldrich filed a lawsuit with the aim of overturning the rating, but this was ultimately dismissed, and the film died at the box office.

Some critics point to what now seem caricatured portrayals of lesbian life, but, despite a few stereotypes, Sister George still remains an important work in early gay cinema. What is great about the film – and what made it way ahead of its time – was the fact that it treated homosexuality not as a problem or stigma but as part of the natural order.

US, 101 mins

Director: Stanley Donen

Writer: Charles Dyer

Cast: Richard Burton, Rex Harrison, Cathleen Nesbitt, Beatrix Lehmann, Gordon Heath, Stephen Lewis

Staircase, investigating the lonely, desperate lives of two ageing male homosexual hairdressers in a drab London suburb, starred two icons of heterosexuality – Richard Burton and Rex Harrison.

Harrison is Charlie, the flighty, dagger-tongued roommate of fellow stylist Harry (Burton). Burton is excellent as the quieter of the two – he is very sympathetic, taking care of his bedridden mother as well as his long-time mate. He keeps his bald head wrapped in a towel turban to protect his business and is also self-conscious about his weight, tugging at his clothes throughout the film. It’s one of the actor’s overlooked roles but by no means his best work.

Admittedly, these two acting superstars took on risky roles, but Harrison seems far more concerned that the audience might think he is ‘that way’ and minces about in a parody of homosexual mannerisms. At the time, he was known as a bit of a homophobe, standing out among the usually tolerant actors of his day. Burton, however, told People magazine, ‘Perhaps most actors are latent homosexuals and we cover it with drink. I was once a homosexual, but it didn’t work.’

Together, the pair come across as a sideshow attraction. We never believe that any relationship, homosexual or otherwise, exists between them as they carp self-consciously at one another, coasting through roles they obviously don’t take seriously in a film they don’t respect. It’s not so much a movie about homosexuals, but a movie about Harrison and Burton playing homosexuals.

US, 113 mins

Director: John Schlesinger

Writer: Waldo Salt

Cast: Dustin Hoffman, Jon Voight, Sylvia Miles

Genre: Hustler movie

Nearly 40 years before Brokeback Mountain (2005), John Schlesinger made the original ‘gay cowboy’ movie.

But nobody called Midnight Cowboy a gay cowboy movie when it first screened. Everybody was too busy being shocked by its portrayal of street hustling and homeless life in New York City.

Midnight Cowboy takes place mostly in the cold, dark, dirty confines of the New York City streets, a world away from the open-air, big-sky country of Brokeback Mountain. But the two movies share a central core: a love story involving two men.

Based on James Leo Herlihy’s novel, Midnight Cowboy dramatises the small hopes, dashed dreams and unlikely friendship of two late-60s lost souls. Cheerful young Texas stud-for-hire Joe Buck (Jon Voight) travels to New York to make his fortune as a gigolo to older women, but he quickly discovers that hustling isn’t what he thought it would be after he winds up paying his first trick (Sylvia Miles). He soon gets together with the tubercular Rico ‘Ratso’ Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman) who expands his services to the male population. The pair become companions as a result of their hard times and reside together in a one-bedroom apartment inside a condemned building.

Buck’s incoherent flashbacks throughout the film throw some light on how he’s ended up as a midnight cowboy. These brief sequences reveal he was raised by two women (his mother and grandmother) in a home without men, perhaps contributing to his homosexual leanings.

Joe and Ratso’s lives continue to plummet, and after a strange run-in with the ‘Warhol crowd’, Ratso becomes deathly ill. The two friends have no means of financial support and a mean New York winter is upon them; thus Buck is forced to earn money for his friend and again finds himself on 42nd Street where the characters of the night reside, and much to his dismay – or pleasure (the audience is left in ambiguity) – must delve into various sexual encounters.

Midnight Cowboy’s gay subtext wasn’t really discussed at the time, although in an article entitled ‘Midnight Revolution’ by Peter Biskind (published in Vanity Fair in March 2005) Dustin Hoffman recalls that while making the film both he and Voight understood the gay themes. ‘“It hit us,” observed Hoffman, “Hey these guys are queer. I think it came out of the fact that we were in the abandoned tenement. We were looking around the set and I said, ‘So? Where do I sleep? Why do I sleep here and he sleeps there? Why does he have the really nice bed? Why aren’t I – yeah, why aren’t we sleeping together? C’mon.’”’

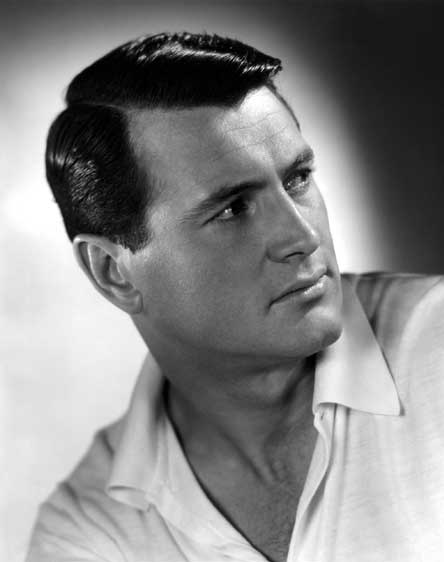

A celebrated actor of Belgian and Scottish descent, Dirk Bogarde was one of Britain’s most popular leading men of the 1950s and early 60s, making his name in mostly routine light comedies (as Simon Sparrow in the popular Rank Doctor series) and melodramas before attracting serious attention for his role as a blackmailed homosexual lawyer in Basil Dearden’s Victim (1961).

The response to his corrupt valet who comes to dominate his ‘master’ in Joseph Losey’s The Servant (1963) seemed to convince Bogarde that he was not just handsome but intelligent and talented, and he took greater care in selecting his roles thereafter.

Bogarde subsequently favoured European cinema and he left Britain in the mid-60s to live in Provence with his friend and manager Tony Forwood. In the 1970s, Bogarde worked with some of the great European directors: he played Gustav von Aschenbach in Death in Venice (1971) for Luchino Visconti and Herman in Despair directed by Werner Fassbinder in 1978.

Bogarde considered Death in Venice to be the peak of his career and felt he could never hope to give a better performance.

In his fifties Dirk Bogarde began a new career as a writer, producing eight autobiographies as well as a number of novels. When Forwood became seriously ill in 1983 they returned to London. In his book A Short Walk From Harrods in 1994, Bogarde describes how he nursed Tony Forwood for the last few months of his life until he died of cancer in 1988.

Dirk Bogarde was made a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Lettres in 1982 and was awarded an honorary Doctor of Letters at St Andrews University. He was knighted on 13 February 1992.

In 1996 he was partly paralysed by a stroke and from 1998 required 24-hour nursing. This, and Forwood’s long illness, made him an outspoken advocate of euthanasia, and he became vice-president of the Voluntary Euthanasia Society. He died of a heart attack at his Chelsea flat on 8 May 1999, aged 78.

‘Rock Hudson’s death gave AIDS a face.’

– Morgan Fairchild

With extreme good looks but no acting experience, Rock Hudson was very much a studio creation, borrowing his screen name from the Rock of Gibraltar and the Hudson River and taking singing, dancing and acting lessons before he made his debut in Fighter Squadron (1948). The tall, strapping young actor went on to become one of the leading male screen idols of the 1950s and 60s, reaching stardom and displaying his first signs of real ability in Magnificent Obsession (1954) and Giant (1956). Hudson later displayed a flair for comedy in a series of sex comedies, often opposite Doris Day, including Pillow Talk (1959), Lover Come Back (1961) and Come September (1961).

Despite such films as the fine science-fiction thriller Seconds (1966) and the sturdy actioner Ice Station Zebra (1968), Hudson’s film career slowly petered out towards the end of the 60s, but his luck turned, however, with his role on the popular 70s police drama McMillan and Wife opposite Susan Saint James. His death in 1985 was caused by complications resulting from AIDS, news of which revealed the homosexuality Hudson had long kept secret.

His last quote, read at an AIDS fundraiser, stated: ‘I am not happy I have AIDS, but if that is helping others, I can, at least, know that my own misfortune has had some positive worth.’ Indeed, his death did have an effect, bringing national attention to the disease and even forcing the then US president Ronald Reagan to actually acknowledge its existence, something he had failed to do throughout the early 80s.

One of the four major British film directors of the early 1960s, openly gay director John Schlesinger’s debut feature A Kind of Loving (1962) fitted perfectly – if perhaps fortuitously – into the regional realism of British cinema of the time.

Schlesinger, though not particularly allied to them in any formal sense, found himself set alongside Tony Richardson, Lindsay Anderson and Karel Reisz as part of a wave of urban filmmaking dealing with hard-edged stories of working-class life.

Whatever else Schlesinger had in mind, he was keen on the frankness of the story about a young man who finds himself trapped by marriage to his pregnant girlfriend. This frankness brought him up against the censor. Referring to a scene in which characters attempt to buy condoms, Schlesinger was told, ‘You could be opening the floodgates. Soon everybody will be doing it.’

Billy Liar (1963) and Darling (1965) showed Schlesinger moving away from the harsh realism that had typified early 1960s British filmmaking. In its place his films were becoming part of a highly fashionable ‘Swinging London’ scene.

Schlesinger’s move to colour came with the big-budget Far From the Madding Crowd, shot by Nicolas Roeg. It marked perhaps the apotheosis of the fashionable 1960s British film, starring as it did both Julie Christie and Terence Stamp, the ‘dream couple’ for British casting directors of the time. Far from the Madding Crowd did not do well at the box office, but it marked his international acceptance as a director of stature, and paved the way for his move to Hollywood.

In America, he made his best-known work, Midnight Cowboy (1969), probably his greatest success commercially and critically, which won Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director and launched a long but rather turbulent Hollywood career for the director. Films such as Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971), The Day of the Locust (1975) and Marathon Man (1976) all bear witness to Schlesinger’s remarkable ability to weave meticulously observed, realistic backgrounds into his complex studies of human relationships.

Schlesinger’s later films included The Believers (1987), a gripping contemporary horror story starring Martin Sheen and Helen Shaver, Madame Sousatzka (1988), about a London piano teacher (Shirley MacLaine) and her gifted young student, Pacific Heights (1990), possibly the first thriller to weave its plot around the problems faced by landlords in their attempt to evict a bad tenant, and The Innocent (1993), an adaptation of Ian McEwan’s Cold War psychological thriller.

His final directorial outing was at the helm of the mild comedy The Next Best Thing (2000), which starred Madonna as a middle-aged woman whose biological clock has ticked so loudly she conceives a baby with her gay pal (Rupert Everett) and then struggles to raise the child with him. Although a fairly minor work in his otherwise bold canon, it was appropriate that in his last film effort before his death in 2003, Schlesinger, who was gay, again tackled the issues of homosexual life and love that had characterised his keenest work.

Many of Schlesinger’s films share a similar outlook. They are tales of lonely people, outsiders in some way, dependent on their illusions, adrift in a world that is bitter but not without sympathy; and to some extent this must have drawn from Schlesinger’s own Jewish, gay background.

The strengths and weaknesses of that view are summed up by Schlesinger’s comment in 1970 that ‘I’m only interested in one thing – that is tolerance. I’m terribly concerned about people and the limitation of freedom. It’s important to get people to care a little for someone else. That’s why I’m more interested in the failures of this world than the successes.’