Patricia Quinn and Little Nell getting friendly with Tim Curry in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) © Photofest

Patricia Quinn and Little Nell getting friendly with Tim Curry in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) © Photofest

Already prominent in the mid to late 1960s were the women’s, civil rights, black power and anti-war movements; developments which inspired younger gay and lesbian activists to radical action and social revolution. All it would take was one incident – any incident – for the Gay Pride movement to progress their cause to entirely new heights.

‘I’m just a sweet transvestite, from Transsexual, Transylvania.’

Frank in The Rocky Horror Picture Show

On Friday 27 June 1969, the world mourned the death of Judy Garland. But the night would not simply be remembered for the Manhattan funeral of a gay icon. It was also to be a sensational turning point in the struggle for gay, lesbian and transgender equality.

On the night of Garland’s funeral, New York City police officers chose to raid the Stonewall Inn, a small bar located on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village. Although mafia-run, the Stonewall, like other predominantly gay bars in the city, was raided periodically.

Typically, the more ‘deviant’ customers (drag queens, butch lesbians and ‘coloured’ gays) would be arrested and taken away while white, male customers looked on or quietly disappeared. On the night in question, the owners of the Stonewall were charged with the illegal sale of alcohol, although it was obvious to most that it had been busted simply because it was a gay bar. The raid began as they all did, with plainclothes and uniformed police officers entering the premises, arresting the staff, and throwing out the customers one by one onto the street.

As the police trashed the bar and smashed the cash register, the ousted gays gathered outside, frustrated that Stonewall was the third gay bar in the Village to be raided and closed in recent weeks. They started to get loud and rowdy; and then no one is really sure what happened next. Could the crowd have been incited by the butch lesbian who resisted arrest, yelling and screaming? Was it the defiant drag queen standing in high heels chanting ‘gay power’? Perhaps emotions were still running high because of Judy Garland’s death, or maybe it was simply the summer heat. But whatever the cause, the crowd, which had grown to several hundred people, totally erupted.

Police called for reinforcements while being hit with coins, bottles, bricks and even a parking meter. They tried to make arrests but hadn’t expected queens to fight back. Surprised and in shock, officers were eventually forced to take refuge and lock themselves inside the Stonewall. To the delight of hundreds of gay onlookers, a group of drag queens taunted the police by singing at the top of their lungs, ‘We are the Stonewall girls/We wear our hair in curls/We wear no underwear/We show our pubic hair/We wear our dungarees/Above our nelly knees!’

‘Truth? Justice? Human dignity? What good are they?’

Alfred in Death in Venice

With the police holed up in the bar as the crowds chanted ‘Gay Power!’ it was clear the gay movement was underway. Similar riots occurred on succeeding nights, followed by protest rallies. The event marked the awakening of gay-rights organisations throughout the US and it’s commemorated annually in Gay and Lesbian Pride Week.

‘In just seven days, I can make you a man. Dig it if you can.’

Dr Frank-N-Furter in The Rocky Horror Picture Show

As a result of the 1969 Stonewall riots and the subsequent shift in attitudes about homosexuality, the media was forced to acknowledge the existence of a gay community and the issues it faced. Although the events in Greenwich Village received little coverage initially, they served as a rallying force and soon many major newspapers and magazines featured in-depth stories concerning the new emergence of homosexual visibility. A Newsweek article commented of the Stonewall riots, ‘In summers past, such an incident would have stirred little more than resigned shrugs from the Village’s homophile population – but in 1969 the militant mood touches every minority.’

By October of 1969, a report issued by the American government’s National Institute of Mental Health urged states to abolish laws against private homosexual intercourse between consenting adults. This report was interpreted by the author of an October Time article as a sign that some tolerance and even support for the gay activists was emerging in the ‘straight’ community.

Cinema also reflected these changing perceptions towards the gay community, and the events at Stonewall seemed to help make positive portrayals of gay characters possible. The release of Mart Crowley’s The Boys in the Band in 1970 coincided with the new activist gay movement and provided Americans with personalised examples of male homosexuals and their struggles. The film centres around a group of unhappy but witty gay men who lacerate each other and themselves, characters like Larry and Hank, who are average guys who just happen to be gay. Friedkin’s film was a major step forward in characterisation, although by no means perfect. It’s often criticised for delving a bit too much into self-hating angst and demoralising confessions: not exactly supportive images for a minority struggling to become visible.

The Boys in the Band (1970)

Although not quite as many gay villains, victims and sissies appeared in the 70s as the 60s, the revelation of homosexuality still caused suicides in Ode to Billie Joe (1976) and The Betsy (1978) and was regularly used to typify sleaziness and evil, from the animated features of Ralph Bakshi (Heavy Traffic, 1973; Coonskin, 1975) and blaxploitation films (Cleopatra Jones, 1973; Cleopatra Jones and the Casino of Gold, 1975), to espionage dramas (The Kremlin Letter, 1970; The Tamarind Seed, 1974; The Eiger Sanction, 1975), cop thrillers (Magnum Force, 1973; Freebie and the Bean, 1974; Busting, 1974), and prison films (Fortune and Men’s Eyes, 1971; Caged Heat, 1974; Scarecrow, 1973). Homosexual rape also marred the backwoods trip of Deliverance (1972), and promiscuous hetero Diane Keaton got murdered by a gay man in Looking For Mr Goodbar (1977).

‘Do you know what lies at the bottom of the mainstream? Mediocrity.’

Alfred in Death in Venice

Nevertheless, throughout the 70s, there was a definite change for the better in gay cinema. Where, in the 60s, sympathetic though unhappy homosexual characters featured in major films like A Taste of Honey, The Leather Boys and The L-Shaped Room, it wasn’t until a decade later that mainstream directors such as John Schlesinger and Bob Fosse would present homosexuality as a valid alternative lifestyle. Fosse’s Cabaret (1972) and Schlesinger’s Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971) proved that gay issues could be treated in a serious adult manner. While Cabaret was a bawdy but inspired musical exploration of 1930s Berlin seen through the eyes of a bohemian club singer (Liza Minnelli) and a pretty-boy bisexual (Michael York), Sunday Bloody Sunday was more low key – an understated, triangular love story in which Glenda Jackson and Peter Finch share the affections of bisexual Murray Head.

Another powerful and poignant movie from the early part of the decade was Christopher Larkin’s A Very Natural Thing (1973), about a young man who leaves the priesthood to settle down in New York, hoping to meet a man to love and share his life with. Honest and well acted, it tackled the subject matter without prurience. Larkin commented at the time: ‘The idea of a film about gay relationships and gay liberation themes comes out of my own personal reaction to the mindless, sex-obsessed image of the homosexual prevalent in gay porno films.’

‘You must never smile like that. You must never smile like that at anyone.’

Aschenbach in Death in Venice

Meanwhile, director Sidney Lumet and writer Frank Pierson delivered a breakthrough box-office hit with Dog Day Afternoon (1975), a fact-based comedy/drama starring Al Pacino as a gay Brooklyn bank-robber trying to finance his male lover’s sex-change operation. Filmmaking at its best, Pierson was rewarded with a much-deserved Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. Pacino later went on to play a sexually muddled cop in William Friedkin’s Cruising (1980), also set in New York, this time centring around the S&M bars of the city.

Other celebrated gay-themed films of the 70s include various underground movies such as Tricia’s Wedding (1971), which featured the drag troupe the Cockettes; Jim Bidgood’s sensual fantasy Pink Narcissus (1971); the films of Jan Oxenberg, such as A Comedy In Six Unnatural Acts (1975); and the films of the late Curt McDowell, including Thundercrack! (1975) and Loads (1985).

Björn Andresen as Tadzio in Death in Venice (1971)

From Italy, in 1971, came Luchino Visconti’s interpretation of Thomas Mann’s classic novella, Death in Venice. Dirk Bogarde starred as an ageing world-famous composer who reassesses his life when his eyes alight on a beautiful teenage boy. Quiet, thoughtful and beautifully composed, Visconti took a difficult story and treated it with restraint and sensitivity. Bogarde was quoted as saying that he’d never better his work in this film.

Meanwhile, in Britain, director Derek Jarman released some of his finest work, including the highly homoerotic Sebastiane (1976), a sincere, respectful story of the martyr. Jarman’s film, infamous for its plentiful, non-exploitative male nudity and all-Latin dialogue, offered an honest detailing of the spirit of Christianity which led to Sebastiane’s refusal of Roman orders to kill a young page.

Also from Britain came the made-for-TV movie The Naked Civil Servant (1975), a biographical film, based on the real life of Quentin Crisp, an Englishman who lived in London. Crisp was an effeminate homosexual, a flamboyant and witty exhibitionist whose conversation was as glittering as the lipstick and mascara he used for effect. The film, full of Crisp’s dry and ironic humour, stars John Hurt in one of the highlights of his career, and explores the story of the extraordinary and courageous life of Crisp, who decided not to disguise his homosexuality, and use it as a weapon instead of a weakness. Although a TV movie, The Naked Civil Servant quickly became regarded as an invaluable document in the history of gay visibility in twentieth-century England.

‘You cannot touch me now. I am one of the stately homos of England.’

Quentin Crisp in The Naked Civil Servant

‘Let’s do the time warp again!’

All in The Rocky Horror Picture Show

‘I would like if I may to take you on a strange journey.’

The Criminologist in The Rocky Horror Picture Show

A large batch of American television movies dealing with gay issues also seemed to surface in the 70s: That Certain Summer (1972) with Hal Holbrook as a gay father coming out to his son; A Question of Love (1978) starred Gena Rowlands as a lesbian mother fighting for custody of her child; and Sergeant Matlovich Vs The US Air Force (1978), which dramatised a real-life challenge to the military’s ban on homosexuality.

The lighter side of the decade’s gay cinema offerings came in the form of a bisexual named Frank-N-Furter (Richard O’Brien) in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975). Based on the British rock musical, it’s primarily a spoof of old monster movies with scenes of bisexual flirtation and seduction thrown in. One of the most enduring examples of homosexuality in film, Rocky Horror bombed on its initial release. However, the marketing people at Fox decided to programme midnight showings and soon people started shouting at the screen, throwing objects across the cinema, and dressing up as their favourite characters. The midnight screenings encouraged even the most down-to-earth guys to dress up in high heels and fishnet stockings and, considering that a large portion of its audience was straight, Rocky Horror allowed heterosexuals to accept homosexuals, and even enjoy aspects of the lifestyle. Quite quickly, the movie became one of the most successful cult films of all time.

Meanwhile, the late, great drag queen Divine provided audiences with even more outrageous camp thrills, mainly courtesy of director John Waters. Multiple Maniacs (1970), Pink Flamingos (1972) and Female Trouble (1974) were sometimes-obscene black comedies extolling crime and exalting the 300-lb female impersonator. Waters’ Divine-less Desperate Living (1977), a lesbian fairy tale, was one of the wildest of all his films.

‘Filth is my life!’

Babs Johnson in Pink Flamingos

Yet these camper films tended to play better with audiences who felt more at ease laughing at gay lifestyles than understanding them. In fact, lesbians and gay men provided cheap laughs throughout the decade in films such as There Was a Crooked Man (1970), MASH (1970), Little Big Man (1970), For Pete’s Sake (1974), Sheila Levine Is Dead and Living in New York (1975) and The Goodbye Girl (1977). Some of the condescending farces that focused purely on homosexuality were simply horrendous: Norman… Is That You? (1976), The Ritz (1976) and A Different Story (1978) are just a few of the exploitative, politically incorrect ’comedies’ that poked fun at faggots.

‘Oh my God Almighty! Someone has sent me a bowel movement!’

Babs Johnson in Pink Flamingos

There were also gay supporting characters, however, who were actually funny, such as Antonio Fargas in Next Stop, Greenwich Village (1976) and Car Wash (1976), and Michael Caine in California Suite (1978). And Foul Play (1978), one of the funniest films of the 70s, had everything a gay man could ask for – San Francisco, camp disco music and saunas – but no gay characters! Like so much else at the time, you had to be in the know to see it as a gay film. Most didn’t and it became an enormous popular success, restoring Goldie Hawn’s box office and launching Chevy Chase and Dudley Moore into starring careers. Now it’s far easier for people to pick up on its gay sensibility and many see Colin Higgins’ film as a gay homage to Hitchcock.

‘There are two kinds of people, my kind and assholes.’

Connie in Pink Flamingos

Interestingly, Colin Higgins had previously scripted an earlier 70s gay favourite which also had no gay characters. Harold and Maude (1971) starred Bud Cort as a young man with a great flair for inspired sight gags, all relating to death, and a wacky 79-year-old woman (Ruth Gordon) as his companion in love and adventures. Higgins later revealed the film was a gay love story in disguise. He stated: ‘I’d have written a wonderful gay love story. But who would have filmed it? So I did the next best thing – I wrote something very quirky and interesting and which hopefully challenged convention.’

‘It stinks of high heaven, and God, dressed as Marlene Dietrich, holds his nose.’

Hedwig in Fox and His Friends

By the end of the decade, one of the most successful foreign films ever shown in the US came out. La Cage aux Folles (1978) was a wildly hilarious French farce centring around a happy gay couple who are forced to pass as straight when one partner’s son, from a previous moment of heterosexual abandon, brings home his prospective in-laws. The film was so successful it spawned a sequel three years later, followed by a third instalment in 1986. However, although La Cage featured out gay characters in a healthy committed relationship (and loving parents to boot), it was a very light-hearted affair and yet another example of how, over the course of the decade, gay-related films had shifted from serious post-Stonewall dramas (Sunday Bloody Sunday, The Boys in the Band, Death in Venice) to clownish camp antics and drag movies. Though in the decade that would follow, with the impact of AIDS, gay-themed movies were about to get a lot more serious...

US, 118 mins

Director: William Friedkin

Writer: Mart Crowley

Cast: Cliff Gorman, Laurence Luckinbill, Kenneth Nelson, Leonard Frey, Peter White, Frederick Combs, Robert La Tourneaux, Reuben Greene

Genre: Black comedy

Mart Crowley adapted his own acclaimed, award-winning 1968 play for the screen, the first Hollywood film in which all of the principal characters were gay. Unlike director William Friedkin’s subsequent effort, Cruising (1980), this picture was well received on its release.

Set in New York, one rainy evening, the story centres around a bunch of gay men who get together to celebrate a friend’s birthday party at a Manhattan apartment, the film’s only setting. The party, for pot-smoking Harold (Leonard Frey), gradually turns into more of an ensemble character assassination as the drink flows and one of the guests, Alan (Peter White), reveals his heterosexuality to the group. The host, Michael (Kenneth Nelson), is the most dominant character but the least happy being gay. In fact, he’s a Catholic riddled with guilt and ends up fleeing to Midnight Mass. Other characters include Michael’s calmer pal Donald (Frederick Combs), a hustler called Cowboy (Robert La Tourneaux) and a bickering couple (Keith Prentice and Laurence Luckinbill).

The characters come out with some wonderful lines such as Michael’s, ‘Show me a happy homosexual and I’ll show you a gay corpse,’ and Emory’s plea, ‘Who do you have to fuck to get a drink around here?’ As the evening wears on though, the quips become more and more waspish, and the bickering sinks into vengeful attacks.

The film has often been criticised for its stereotypical treatment of gay men, showing simply campy, bitchy behaviour. Certainly, the boys display varying degrees of queenish antics, with references to The Wizard of Oz (‘He’s about as straight as the yellow brick road’) and Sunset Boulevard (‘I’m not ready for my close-up, Mr DeMille, nor will I be for the next two weeks’) and at one point, a guest is even seen perusing The Films of Joan Crawford. However, this film that so riled Gay Lib activists in the 70s has developed into an important historical document. Most now recognise its revolutionary qualities; that it was immensely valuable to have some acknowledgement of gay existence rather than silence. Although the film focused on the sadness and loneliness of being a homosexual, it gave a sense of various gay identities – the flamboyant queen, the clone, the straight-acting Ivy League Jock, the suited businessman, and so on. And none of them died at the end.

A breakthrough work on a taboo subject, Boys in the Band is certainly reflective of its times. ‘I knew a lot of people like those people,’ Crowley said of his characters. ‘The self-deprecating humour was born out of low self-esteem, from a sense of what the times told you about yourself.’

Indeed, Crowley’s entertaining yet quietly thoughtful script is full of pathos, bitchiness, loneliness and jealousy, and under William Friedkin’s generally sensitive, guiding hand, the film builds to a powerful climax.

Written on the eve of Gay Liberation and released in 1970, less than a year after the infamous Stonewall riots, Boys in the Band finally put to rest the Production Code’s repressive stance on gay subject matter and became a catalyst for future positive portrayals. The picture really was ahead of its time and, although it looks a little dated now, there is still much to enjoy.

Italy/France, 130 mins

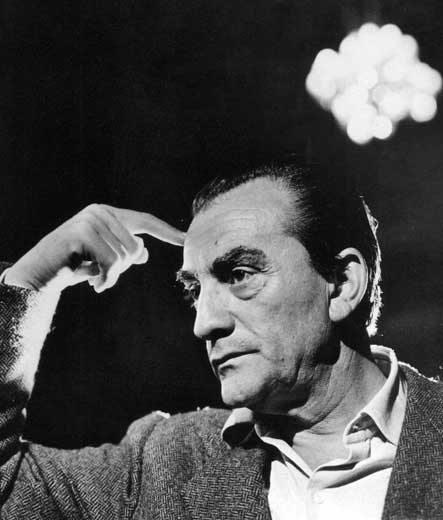

Director: Luchino Visconti

Writers: Luchino Visconti, Nicola Badalucco.

Cast: Dirk Bogarde, Romolo Valli, Mark Burns, Nora Ricci, Marisa Berenson, Carole Andre, Björn Andresen.

Genre: Period drama

‘The theme is not only homosexuality, but there is homosexuality. Although no sex at all. Still, Hollywood wanted me to change the boy to a girl. They do not even know of Thomas Mann!’

– Luchino Visconti

Dirk Bogarde gave the finest performance of his career, in fact one of the very best ever on screen, in Visconti’s superb 1971 version of the Thomas Mann 1912 novella.

Bogarde is the avant-garde composer Gustav von Aschenbach (loosely based on Gustav Mahler), taking a convalescent holiday at the Venice Lido after the death of his child, the disastrous reception of his new compositions and various complications in his personal life back in Germany.

Trying to escape this stressful period, relaxing in the inspirational but decadent city, he develops an attraction to a beautiful boy sporting on the beach. Having only intended to stay for just a short period, he soon becomes so entranced by the beauty of this young boy, Tadzio (Björn Andresen), that he finds excuses to stay there longer. Dismissing hotel staff and porters with a flick of his wrist and gazing longingly at the young boy’s figure, Bogarde’s Aschenbach is perfectly suited to the crumbling decadence of the Venetian locations. He lingers, despite possessing privileged knowledge about a cholera epidemic sweeping the city. Ultimately, he is thrown into epiphanic agony as he falls utterly in love with this adolescent who embodies his ideal of beauty, that which he has been striving to achieve in his work.

The composer continues to watch Tadzio, despite what he’s heard about the onset of cholera. Convinced of a mad and passionate truth in this infatuation and pleased by the efforts of a barber to make him look younger, Aschenbach obviously cherishes his obsession with Tadzio. But when news of the epidemic spreads, the hotel guests begin to leave, and one morning Aschenbach goes down to the beach to find only Tadzio there. Sitting in his beach chair, he is mesmerised by the young boy who, posing like a Greek statue, raises his arm towards the horizon. As he watches the boy pointing, he thinks it’s an invitation, so he reaches up too. But it’s too much of a struggle and Aschenbach quickly collapses back into his chair and dies. His dying desire lives on.

The composer’s demise is inevitable and evident from early in the film. From the thick black smoke of the steam train bringing him to Venice to the final hint in the barber’s shop that he is being embalmed as a simulacrum of the way he might once have appeared, Aschenbach is on a path from which he cannot diverge. In a sense, he is dead from the start.

A surprisingly subtle and intriguing tale of an obsessive quest, this wonderfully slow-paced film is also about the spiritual history of a man who knows he is dying. Aschenbach knows he will meet his own doom, all in his quest to understand the meaning of perfection, as embodied in the form of Tadzio.

A film of undeniable but unconventional beauty, don’t expect special effects, car chases or fights. But sometimes simple is best. Nor are there any perverted sex scenes; the interaction between man and boy is limited to stolen glances from afar and the occasional smile.

Death in Venice is indeed about Aschenbach’s death but another death that we witness is a more abstract one; that of the composer’s notions about the nature of art. Flashbacks reveal Aschenbach’s colleague Alfred (Mark Burns) arguing about Art with him. Alfred’s argument – ‘Art is ambiguity, always’ – wins through the person of Tadzio, a living embodiment of the ambiguity of physical perfection. Aschenbach thinks he is appreciating Tadzio on a spiritual level but he soon realises that this has become hopelessly confused with true feelings of love. This conflict can never be reconciled.

Mahler’s Third and Fifth Symphonies are woven throughout the film. Particular emphasis is placed on the Adagietta of the Fifth, which first plays over the opening credits, then keeps reappearing. The music haunts the film, as do the quiet whispers of sound that help create the film’s almost surreal environment. The delicacy of the soundtrack evokes the mood of Aschenbach’s last days and his obsession with the face of Tadzio.

Pasquale De Santis’s cinematography is also exquisite, while the beauty of Visconti’s shots, particularly at the end, is sublime but also comforting, bathed in hazy Venice sunshine.

Visconti described the Thomas Mann novella from which the film was adapted as ‘a mighty subject for a motion picture’. He fought hard to make Death in Venice. Arguments over casting and cuts in the original budget plagued the production. Originally the producers were horrified by the film’s lyrical homoeroticism. However, the Warner Bros executives allowed Visconti to complete his film following large box-office returns from his previous feature The Damned.

Renowned for his uncompromising demands and need for perfection, a 20-minute featurette on the British DVD release of Death in Venice provides an interesting insight into life on set of this film – the endless takes and lengthy days waiting around for the correct conditions. The short documentary was made over a very long day of filming in which just one sequence of less than two minutes was shot. During the day, Bogarde described how Visconti concentrated on absolute craftsmanship: ‘Everything has to be absolutely perfect for him,’ he explained. ‘The reflection of a glass dish on a child’s face, in a scene where I am having a row with somebody else, is equally important to him as the row!’

Many critics were taken aback by the film’s controversial subject matter, and Death in Venice was met with almost universal disapproval and misunderstanding when it was first released.

Nevertheless, Visconti’s masterpiece won awards all round the world. Dirk Bogarde was deeply grateful to his director, saying, ‘Visconti was the greatest teacher and professor I’ve ever had in my life. I’ve learned so much from him.’ To top it all, in 1971, Visconti won the special Grand Prize at the 25th anniversary of the Cannes Film Festival, honouring the film and the career of its director.

US, 65 mins

Director: James Bidgood

Cast: Bobby Kendall, Charles Ludlam, Don Brooks

Genre: Erotic fantasy

James Bidgood’s Pink Narcissus is an unwavering celebration of the male body within a fantasy world of epic indulgence. Complex, beautiful and very sexy, it’s a film unlike any other. There is no dialogue but every scene is chockfull of symbolism.

An outrageous but breathtaking erotic poem, the film focuses on the daydreams of a beautiful young boy prostitute who, from the seclusion of his ultra-kitsch apartment, dreams a series of interlinked narcissistic fantasies. The self-obsessed boy imagines himself as a Roman slave chosen by the emperor, as a triumphant sparkle-suited matador vanquishing the bull, an innocent wood nymph romping in the woods, a harem boy in the tent of a sheik. But reality constantly intrudes through the depraved lives of the other street people, leather-clad bikers and slaves and visits from the johns. His narcissism is marred by one great fear – growing old and losing his looks.

Bobby Kendall in Pink Narcissus

Filmed in richly saturated colours, brilliantly styled and created by Bidgood, Pink Narcissus was made in his own tiny apartment using homemade and improvised sets and props. It was shot over seven years in a haphazard fashion between 1964 and 1970 on 8mm. With its highly charged hallucinogenic quality, its atmosphere of lush decadence, and its explicit erotic power, Pink Narcissus is a true landmark of gay cinema. As filmmaker Richard Kwietniowski once wrote: ‘Should the film be aligned with the work of Anger and Jarman in experimental cinema? Or in the art world, with photographers like Pierre et Gilles, who attempt similar levels of artifice? Is it just erotica from the beefcake era, or the most utopian home movie ever made?’

Pink Narcissus was shrouded in mystery following its initial release in 1971. The production company, Sherpix Productions, had edited the film without the creator’s consent and so, as a result, Bidgood was credited as ‘Anonymous’, which led to critics surmising who had actually directed the film. Wrongly, it was attributed to filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger and Andy Warhol, until the truth emerged that it was in fact Bidgood.

The clues were there, however, with Bidgood having already achieved success as an artist and photographer, many of his photographs featuring the film’s star Bobby Kendall. Throughout most of the 1960s, Bidgood had contributed photographs to physique magazines such as The Young Physique under the pseudonym ‘Les Folies des Hommes’.

Considered lost for many years, film historians worked at restoring Bidgood’s fantasy and, eventually, it was rescued from obscurity at the 1984 New York Gay Film Festival where screenings were packed out. More recently, in the summer of 2007, the film was released complete and uncut on DVD through the respected British Film Institute label. Accompanied by a world-exclusive filmed interview with the director, in it Bidgood stated: ‘Most gay men are narcissists. We love men. We love ourselves, and that was what the film was about – someone who was in love with himself and had fantasies in which he was always the object of love or whatever.’

Thanks to the restoration of the film, Pink Narcissus will now always have a certain cult status as new generations of gay viewers become mesmerised by the film’s stunning star – the gorgeous and enigmatic Bobby Kendall.

US, 124 mins

Director: Bob Fosse

Cast: Liza Minnelli, Joel Grey, Michael York, Helmut Griem, Marisa Berenson, Fritz Wepper

Genre: Musical

One of the most brilliant musicals ever made, Bob Fosse’s Cabaret is a truly inspired version of Christopher Isherwood’s 1939 memoirs and bisexual tales of pre-WWII Berlin.

In this dazzlingly choreographed story of love, decadence and Nazi stormtroopers, Liza Minnelli stars as fame-hungry cabaret singer Sally Bowles, who becomes embroiled in a love triangle with an impossibly pretty bisexual English teacher Brian Roberts (Michael York) and wealthy German toff, Maximilian von Heune (Helmut Griem), in the rotting decadence of 1930s Berlin.

As the film opens, outside on the street, the Nazi party is growing into a brutal political force; but away from this, we are welcomed inside the Kit Kat Club, where the girls, the boys and even the orchestra are beautiful. Brian enters this strange café society and straight into starry-eyed Sally’s decadent life – all fun, booze and sex. Straight sex, that is. Brian, having thought he was gay, is a little confused. Sally taunts him: ‘Maybe you just don’t sleep with girls.’ He doesn’t deny it. When Baron Maximilian arrives on the scene, he invites the pair to his mansion with the sole intention of corrupting them both. It’s clear that the two men become more than just buddies. Although we don’t see them in bed together, when Brian later shamefacedly rejects Max’s gift of a gold cigarette lighter, the implication is that something has gone on.

Later, during a row about Max, Brian snaps at Sally, ‘Screw Max!’ ‘I do!’ she replies, and he retorts, ‘So do I!’ Sally soon winds up pregnant but has an abortion without telling him; she explains cryptically: ‘How long would it be before you…’

Fosse makes such candid points about Brian’s bisexuality with tasteful emphasis. The director also stokes Cabaret with an edgy desperation as the characters sweat blood to stay carefree in a world overshadowed by the Third Reich’s leather-clad menace. Fosse handles the political material during the time of Hitler’s rise to power with style and integrity and the film’s energy, musical set pieces and performances still enthral to this day. Minnelli shines and sparkles throughout and York is excellent as the young bisexual Englishman, while Joel Grey’s depiction of a grotesque cabaret MC is yet another highlight of this knockout musical. With patent-leather hair, rosy cheeks and thick drag-queen eyelashes, he relishes the creepy character’s sleaziness and ‘Money’, his duet with Minnelli, is a showstopper.

This extraordinary adaptation of the Kander-Ebb musical won eight Academy Awards, including those for Best Director (Fosse), Best Actress (Minnelli) and Best Supporting Actor (Grey).

US, 95 mins

Director/Writer: John Waters

Cast: Divine, David Lochary, Mink Stole, Mary Vivian Pearce, Edith Massey, Danny Mills, Channing Wilroy, Cookie Mueller

Genre: Cult camp comedy

If Clockwork Orange was a deliberate exercise in ultra-violence, Pink Flamingos is a deliberate exercise in ultra-bad taste. With no budget, grotesque images and the striking drag queen Divine, this movie soon attracted an endearing legion of admirers. It’s still shown at select theatres and often at gay and lesbian festivals around the world with fans queuing to cheer for Babs and Cotton, hiss Connie and Raymond, quote endless lines, and have a great time.

The plot of this seminal camp flick follows the adventures of Sleaze Queen Babs Johnson (Divine), a fat, style-obsessed criminal who lives in a trailer with her mentally-ill, 250-pound mother Edie (Edith Massey), her hippie son Crackers (Danny Mills) and her travelling companion Cotton (Mary Vivian Pearce). They’re trying to rest quietly on their laurels as ‘the filthiest people alive’. But competition is brewing in the form of Connie and Raymond Marble (David Lochary and Mink Stole), ‘two jealous perverts’, according to the script, who sell heroin to schoolchildren. Finally, they challenge Divine directly, and battle commences.

Raymond and Connie try to seize Bab’s title of ‘filthiest person alive’ by sending her a turd in the mail and burning down her trailer. The Marbles kidnap hitchhiking women, have them impregnated by their servant Channing (Channing Wilroy), and then sell the babies to lesbian couples. As Raymond explains, they use the dykes’ money to finance their porno shops and ‘a network of dealers selling heroin in the inner-city elementary schools’.

Pink Flamingos has cult qualities in the same way The Rocky Horror Picture Show does; everyone in the film has something odd about them and both movies joyfully celebrate their uniqueness. Waters’ film has endless memorable moments (who could forget?) – the shrimping scene with David’s blue and Mink’s orange pubic hair, Divine’s infamous faeces-snacking, brown teeth and all, sex with a chicken, eating people alive, incestuous fellatio with her son, and hard-core pornography. This commercial feature surely must be the first and only to end with the star eating dogshit.

Pink Flamingos is now over 40 years old. Waters recently had the film blown up from 16 to 35mm and ‘restored’ ready for forthcoming video and DVD releases which feature a few never-before-seen outtakes, self-critical commentary by Waters (‘You can see the bad continuity in this scene’), a new stereo soundtrack and the hilarious original trailer, which is made up only of shocked reactions from people who have just seen the picture.

Many won’t enjoy either Crackers and Cookie’s chicken-shagging scene or Babs’ turd eating, but these sequences are what put the film on the map, brought Waters all the publicity, negative and otherwise, and gave Pink Flamingos a permanent place in camp film history.

UK, 100 mins

Director/Writer: Jim Sharman

Cast: Tim Curry, Susan Sarandon, Barry Bostwick, Richard O’Brien, Jonathan Adams, Nell Campbell

Genre: Cult camp comedy

Richard O’Brien’s wacky stage show was turned into the definitive cult movie thanks mainly to Tim Curry’s camp Dr Frank-N-Furter, Meat Loaf in a deep freeze, a script full of kitsch appeal, and that all-singing-all-dancing, toe-tapping ‘Time Warp’ finale. It was the movie that inspired us all to take a few steps to the left and showed us there’s a disco queen inside each of us!

The Rocky Horror Picture Show is an outrageous assemblage of the most stereotypical science-fiction movies, Marvel comics, Frankie Avalon/Annette Funicello outings and rock ‘n’ roll of every vintage. Running through the story is the sexual confusion of two middle-American, ‘Ike Age’ kids confronted by the complications of the decadent morality of the 70s, represented in the person of the mad ‘doctor’ Frank-N-Furter, a transvestite from the planet Transexual.

O’Brien, who wrote the book, music and lyrics calls it ‘something any ten-year-old could enjoy’. The original play opened in London at the Royal Court’s experimental Theatre Upstairs as a six-week workshop project in June 1973, and was named Best Musical of that year in the London Evening Standard’s annual poll of drama critics. Lou Adler, who was in London, saw The Rocky Horror Show and promptly sewed up the American theatrical rights to the play within 36 hours.

Filming of The Rocky Horror Picture Show began a year later at Bray Studios, England’s famous House of Horror, and at a nineteenth-century chateau, which served once as the wartime refuge of General Charles de Gaulle.

The film version retains many members of the original Theatre Upstairs company. Repeating the roles they originally created in the theatre are Richard O’Brien (Riff Raff), Patricia Quinn (Magenta), Little Nell (Columbia) and Jonathan Adams (who played the Narrator on stage and in the film appears as Dr Scott).

With O’Brien co-writing the film’s screenplay, the result is a faithful adaptation of the original...

On the way to visit an old college professor, two clean-cut kids, Brad Majors (Barry Bostwick) and his fiancée Janet Weiss (Susan Sarandon), run into tyre trouble and seek help at the site of a light down the road. It’s coming from the Frankenstein place, where Dr Frank-N-Furter (Tim Curry), a transvestite from the planet Transexual in the galaxy of Transylvania, is in the midst of one of his maniacal experiments – he’s created the perfect man, a rippling piece of beefcake christened Rocky Horror (Peter Hinwood), and intends to put him to good use (his own) in his kinky household retinue, presided over by a hunchback henchman named Riff Raff (Richard O’Brien) and his incestuous sister Magenta (Patricia Quinn), assisted by a tap-dancing groupie-in-residence, Columbia (Little Nell).

Meanwhile, an oafish biker, unwed Eddie (Meatloaf), ploughs through the laboratory wall, wailing on a saxophone. Frank puts a permanent end to this musical interruption without thinking twice until the old professor Brad and Janet set out to visit, Dr Scott (Jonathan Adams), turns up at the castle in search of his missing nephew, the juvenile delinquent Eddie. He knows that Frank-N-Furter is an alien spy from another galaxy, and goes to turn him in, but Frank moves too fast, seducing first Janet, then Brad into his lascivious clutches. Overwhelmed by a newfound libido, Janet hotly attacks the stud Rocky Horror while Brad is under the covers with Frank.

Before Dr Scott can bring justice and morality into this topsy-turvy Transylvanian orgy, Frank-N-Furter has turned his captives to stone, in preparation for a new drag revue ‘experiment’, and Riff Raff and Magenta reappear in Transylvanian space togs to wrest control of the mission from Frank-N-Furter, whose lifestyle is too extreme even for his fellow space travellers. When his lavish histrionic claims of chauvinism fail to soften up Riff Raff and Magenta, Frank-N-Furter tries to escape, only to be gunned down by their power ray-guns. Rock rushes to save his creator, but he, too, is blasted to outer space by the militants.

Brad, Janet and Dr Scott are left in a fog, incapable of readjusting to the normalcy of the life they’ve left behind in Denton, now that they’ve tasted the forbidden fruits of the Time Warp.

Richard O’Brien’s cross-dressing sensation will forever be an acquired taste but elicits a fiery passion in devoted fans. Like many cult movies, it was rejected by most viewers on its initial release; but after late-night screenings took place in New York, the cult began to develop. Devoted fans started to arrive at theatres in costume ready to join in the musical madness. One of the few movies that consistently inspires dancing in the aisles, throughout the film audience members recite the dialogue simultaneously with the characters on screen, many even mocking the characters or coming up with improvised quips aimed at the actors involved. Water pistols are squirted, toilet rolls thrown and playing cards tossed at the screen. Such screenings become major advertised events.

This camp classic always deserves another look and was the perfect picture for DVD. The various discs include an amazing line-up of essential extras for Rocky fans. Of course, they’re not all on one edition and fans will have to buy special editions to collect them all. However, extras that are around include commentaries by O’Brien and other cast members, the deleted musical sequence ‘Superheroes’, which has been edited back into the film, ‘The Theatrical Experience’ – a branching function that gives you an in-theatre experience viewing option to allow DVD owners to see the crowd’s reaction or the performers on stage at certain points as they watch the film – the engrossing documentary Rocky Horror Double Feature, deleted scenes, outtakes including 11 alternate takes on key scenes in the film, excerpts from VH-1’s ‘Behind-the-Music’ and ‘Where Are They Now?’, featuring interviews with Susan Sarandon, Barry Bostwick, Richard O’Brien, Patricia Quinn and Meatloaf, two lively singalong songs, two theatrical trailers and loads of photo galleries. The film company only releases all of these special editions because the cultural movement surrounding The Rocky Horror Picture Show continues to this day. And the fact that there’s still such huge interest, more than three decades after the film’s original release, is surely a testament to its status as the ultimate piece of interactive performance art.

UK, 80 mins

Director: Jack Gold

Cast:John Hurt, Patricia Hodge, John Rhys-Davies

Genre:Biopic

Quentin Crisp has been described as one of England’s works of art. In 1908, in Surrey, England, Mrs Pratt, nursery governess and solicitor’s wife, gave birth to her last child, Dennis. In the late 1920s, Dennis gave birth to the character that he would become for the remainder of his life, Quentin Crisp.

‘Even a monotonously undeviating path of self-examination does not necessarily lead to a mountain of self-knowledge. I stumble toward my grave confused and hurt and hungry...’

Thus ends Crisp’s unflinching autobiography, The Naked Civil Servant, published in 1968. Seven years later, Thames Television adapted the book, turning it into a remarkable and poignant film. Featuring an award-winning performance by John Hurt, the drama of Quentin’s youth is recaptured in 1930s England.

Crisp himself introduced the piece, which gave us the opportunity to compare Hurt’s performance against the real thing. And what a performance. Not only are the mannerisms and affectations delivered with precision and realism, but the examination of the character within is poignantly and simply revealed.

Crisp’s world was one of brutality and comedy, of short-lived jobs and precarious relationships. It was a life he faced with courage, humour and intelligence. He publicly declared his homosexuality at a time when this alternate lifestyle was still an offence punishable by imprisonment in Great Britain.

Given to blatant exhibitionism, Crisp endured almost constant beatings from local yobs who were threatened by his flamboyant style. He engaged for a time in street prostitution, although, in his own retrospection, he felt this was to look for acceptance more than income. Slowly, he began to assemble a group of friends who were in their own ways equally flamboyant and outrageous, and found himself in the arty world of Soho bohemia.

The film details how, just before the Second World War, he found work, lodgings and refuge by way of an unnamed ballet teacher, played outrageously in the film by Patricia Hodge. Exempt from war service due to his ‘sexual perversion’, he was employed at a government art school on the recommendation of the ballet teacher, thus becoming the ‘naked civil servant’. In his own words, ‘The poverty from which I have suffered could be diagnosed as “Soho” poverty. It comes from having the airs and graces of a genius and no talent.’

The film portrays an individual who finds himself an alien to all that convention provides. It is produced with an element of sophistry and bitter wit that seems to reflect Crisp well. Its narration plays straight to the audience, emphasised by the use of caption boards, reminiscent of old silent movies.

Crisp’s search for enduring love remained unrequited, with the closest candidate being ‘Barndoor’ (John Rhys-Davies), with whom he shared his one-room Chelsea flat for a number of tumultuous years.

Crisp drifts from circumstance to circumstance in an amazingly passive way. In fact, the only time we see any self-generated activity is when he chooses to defend himself against charges of perversion and solicitation levelled at him by two London constables. Ever mindful of his audience, he stands in the witness box and exposes the inaccuracies of their testimony.

Having survived the court case, and with the war behind him, our last view of Crisp is in a park in London in the early 1970s. He wryly observes that the clothing that had earned him regular beatings from the town toughs is now the uniform of the youth culture. As four younger versions of those earlier toughs try to extort a pound each from him on threat of alleging he’d sexually assaulted them, he aloofly informs them that he is immune to their threats now. ‘I’m one of the stately homos of England’, he sniffs, and minces away as the credits roll.

This excellent film was a Prix Italia and Emmy winner, whilst John Hurt’s memorable performance earned him a BAFTA award for Best Actor.

Fans of the film will probably already know that Crisp later moved to a studio flat in New York in the 1980s. Happily ensconced in Manhattan life, he was immortalised in Sting’s song ‘An Englishman in New York’. What many may not know, however, is that Crisp actually died on English soil, on 21 November 1999, while preparing for a one-man show.

Germany; 123 mins

Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Writers: Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Christian Hohoff

Cast: Peter Chatel, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Karlheinz Bohm, Adrian Hoven

Genre: German Drama

Fox and His Friends was Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s first specifically male gay-themed film and on its release in 1975 was described by a reviewer for The Times in London as ‘one of the best films ever made about the life of homosexuals, their passions, their quarrels…’ Meanwhile, a New York Times writer remarked that it was ‘the first serious, explicit but non-sensational movie about homosexuality to be shown in this country’.

Franz Biberkopf, known as ‘Fox’ and played by Fassbinder himself, is a carnival worker at a loose end when his lover is arrested and the police shutter their carnival booth. In need of cash for his weekly lottery purchase, Fox lets himself be picked up in a public lavatory by an elegant older man named Max, an antique furniture dealer. At Max’s house, he meets two younger gay men who have expensive tastes and images to uphold. The next day, Fox wins 500,000 marks in the lottery, and Max’s friends suddenly turn into his friends, especially Eugen, the heir to a bookbinding firm that’s short of cash. Fox and Eugen become lovers.

Fox, who’s brash, uncouth, warm-hearted and naïve, dominates at first, or seems to, but soon he is tamed and exploited by the effete and bourgeois Eugen. Fox’s winning lottery ticket is used to rescue Eugen’s collapsing family business, and he is eventually jilted, broke and without recourse. His dead body is found next to an empty pill bottle by two teenagers who pick through his pockets while two of his old friends flee to avoid involvement.

There’s a level of dry humour played throughout the story, which is both comedy and satire. Numerous scenes play up the differences between Eugen and Fox, and especially Fox’s attempts to copy the social graces of the wealthy. Yet the overall effect is that of tragedy, as Fox allows himself to be used and abused, and in the final sequences come constant blows to any chance of a happy ending.

UK, 91 mins

Directors: Derek Jarman, Paul Humfress

Cast: Leonardo Treviglio, Barney James, Richard Warwick, Neil Kennedy,

Genre: Historical drama

Derek Jarman’s debut feature film shocked audiences with its frank portrayal of homosexuality, violence, and the ultimate martyrdom of the Catholic saint Sebastiane in 303 AD.

A visually striking fantasy, Sebastiane begins at the court of Emperor Diocletian in an unforgettable sequence of Roman excess and Bacchanalian sexuality. Similar in tone to the opening sequence of Ken Russell’s grotesque historical drama The Devils, which Jarman designed in 1971, the film is also reminiscent of the orgiastic fantasies of Federico Fellini’s Satyricon and Cecil B DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross. Jarman is conscious of these allusions though, and at one point a Roman soldier in the film, dreaming of the golden era of Rome, mentions ‘Cecilli Mille’ and ‘Phillistini’s Satyricon’.

Accused of standing up for a Christian, Sebastiane (Leonardo Treviglio), friend of the emperor and captain of his guard, is demoted to mere soldier and banished from Rome to an isolated Sicilian encampment. This remote coastal place proves to be both a barren wasteland and an oasis of freedom where the men are free to act out homosexual fantasies and explore their hidden desires. However, Sebastiane angers outpost captain Severus by ignoring his sexual advances and devoting himself to God, resulting in a violent battle that ends ultimately with a stunningly homoerotic execution.

So, in Jarman’s vision of the saint who died on a cross, Sebastiane is killed not simply for his Christian beliefs but because he refuses the advances of the sadomasochistic Severus.

The film contains probably the most classic homoerotic play-fight, which is thrilling, arousing and to some degree disturbing. In fact, the whole film is filled with memorable cinematography and symbolic imagery. Co-directed with Paul Humfress, this profoundly personal work is visually stunning. Though verging on the pornographic with its vast array of handsome naked men who practise for battle and have sex together, the film is more than an arty gay cult porno. It is an intriguing play on the male psyche and juxtaposes multiple themes: unrequited love; social acceptance of sexual thought; the demands of society upon the individual; sexual desire in an exclusively male environment; and the requirements imposed by religious values.

The film does, however, suffer from one, not-uncommon failing – that the best-looking actor is given the largest role but delivers the weakest performance. Treviglio’s Sebastiane is oh-so-handsome yet far less interesting than the rest of the troubled, bullying, awkward or horny soldiers in the platoon.

Nevertheless, with its fabulous photography, Latin dialogue (with English subtitles), and an evocative, ambient-style score by Brian Eno, Sebastiane is a dreamlike, avant-garde exploration of the soul that benefited from a deserving, yet surprisingly strong, commercial release in Britain and major US cities.

France/Italy, 99 mins

Director: Edouard Molinaro

Cast: Ugo Tognazzi, Michel Serrault, Benny Luke, Michel Galabru, Claire Maurier

Genre: Farce

La Cage aux Folles, one of the most successful foreign-language films ever shown in America, was a huge hit. An undeniably loveable and unpretentious movie, audiences raved over the two main characters in this camp classic – gay lovers Albin and Renato.

Ugo Tognazzi stars as Renato, the owner of a nightclub that features a transvestite revue, while Michel Serrault plays his lover, a neurotic drag queen.

It’s all a bed of roses for the quirky couple until Renato’s love-struck son Laurent (the offspring of a youthful indiscretion) returns to announce that he is engaged to the woman of his dreams, a girl whose father happens to be a strict upholder of public morals. The father of the bride-to-be is a homophobic politician and, although Laurent is comfortable with his gay parents, he needs the man’s approval if the marriage is to go ahead.

With no way of avoiding a meet with the future in-laws, Renato and Albin do their best to conceal their lifestyle, radically altering the décor of their home, from frilly flamboyance to a more subtle, understated style. Even the couple’s maid, a handsome wannabe who usually struts around the house in little more than a skimpy pair of hot pants, is ordered to clean up his image and dress in a proper butler’s uniform. But attempts to consign all signs of gayness to the closet meet with disaster and the increasingly frantic situation provides ample opportunity for slapstick laughs.

As the big night approaches, when they will finally meet the ultra-conservative in-laws-to-be, it becomes clear that Albin will have to pull off the performance of his life. With the aid of a wig, a dowdy housedress and a newly perfected, falsetto voice, he is introduced to the guests as Renato’s wife.

It’s Serrault and Tognazzi’s fine performances that really make Edouard Molinaro’s intrinsically theatrical comedy sparkle. They sail through the whole affair with seemingly boundless, kitsch conviction, but while there are many moments that are excruciatingly funny, there are also one or two others that are genuinely heartbreaking.

La Cage was so successful it spawned two sequels, a Tony-award-winning musical and a Hollywood remake. In La Cage aux Folles II (1981), directed again by Molinaro, the inspired lunacy of the first outing is turned into a caper film with the couple getting involved with gangsters, spies and the police. Meanwhile, five years later, in La Cage aux Folles III: The Wedding (1986), the couple stand to inherit a fortune if Albin can marry and produce an heir to validate his claim. The third instalment was the weakest though, proving that even the French can do bad sequels just like their American counterparts.

American remakes can be awful too, although The Birdcage (1996), with Robin Williams and Nathan Lane taking on the roles of the gay lovers, was actually quite impressive. Mike Nichols’ update of La Cage had Williams as the outlandish nightclub owner, this time in Miami Beach, with Lane as his partner Albert.

Born Harris Glenn Milstead, the ‘world’s most famous transvestite’ Divine grew up down the street from high-school pal John Waters and became a cult figure as Waters’ long-time leading performer. It was Waters, along with make-up artist Van Smith, who transformed the flamboyant and brilliantly talented actor into the horror show Divine, forever associated with vile, repulsive acts and attitude to match.

The oversized female impersonator developed his persona in such early Waters efforts as Roman Candles (1966) and Eat Your Makeup (1968), as a Jackie Kennedy-obsessed fashion groupie, The Diane Linkletter Story (1970), as the suicidal heroine, and the silent Mondo Trasho (1970), as a blonde bombshell who accidentally runs over a foot fetishist-pedestrian.

In 1970, Divine and Waters released their first full-length talking film Multiple Maniacs, the dark, funny and violent story of Lady Divine, leader of a Manson-like crime family. They followed with the classic Pink Flamingos (1972), a gritty, obscene but somehow heart-warming comedy of ill manners that firmly established both director and star. Starring as Babs Johnson, ‘The Filthiest Person Alive’, Divine turned in a star-making performance. Even his famed devouring of dog turds at the film’s close couldn’t overshadow his genuine comic gifts.

Divine was even more brilliant in the tour de force Female Trouble (1974), in which he aged from a rebellious, high-school girl into a deranged, death-row inmate. He also played his first male role in this film and, through the magic of cut-rate special effects, even had sex with himself.

Next, ‘the most beautiful woman in the world’ took his persona to the stage, first performing in San Francisco with a troupe called The Cockettes in such fare as ‘Journey to the Center of Uranus’ and ‘The Heartbreak of Psoriasis’. He made his New York debut in Tom Eyen’s Women Behind Bars (1976) and after its success there also played it to London audiences. Eyen’s second play for Divine, The Neon Woman (1978), ran Off-Broadway and then to packed houses in San Francisco, Toronto, Provincetown and Chicago.

Divine returned to the screen for Waters in the amusing Polyester (1981), which featured the infamous Odorama cards for audiences to scratch and sniff scents depicted on screen, before working with other film directors. Paul Bartel’s Lust in the Dust (1985) was the first major film in which the queen of drag parted company with Waters. Bartel’s amusing sagebrush satire was quite a funny, irreverent send-up of the western, which re-teamed Divine with his Polyester co-star Tab Hunter. Meanwhile, Alan Rudolph’s Trouble in Mind, made in the same year, took Divine out of drag for his role as Hilly Blue, a powerful gangster in the fictitious Rain City.

Not only did he act, but Divine also found worldwide fame as a disco-diva recording star and club attraction, especially in gay venues. Beginning in 1978, he cranked out eleven international hit dance singles, including ‘Shoot Your Shot’ (a Gold single in Holland) and ‘You Think You’re a Man’ (which reached number 17 on the British charts and number 5 in Australia). He recorded primarily with producer Bobby Orlando (who oversaw the Pet Shop Boys’ first tracks), before switching to the team of Stock, Aitken and Waterman (whose line-up included Kylie Minogue and Dead or Alive). Divine toured the world with his solo cabaret act of disco and outrageous humour, performing over 900 times in more than 19 countries.

Divine’s biggest hit came with Waters’ mainstream comedy Hairspray (1988), playing both proud Mom Edna Turnblad (his trademark wigs and outlandish make-up somewhat toned down) and TV station manager Arvin Hodgepile. He was about to guest star as Uncle Otto on the Fox programme Married... With Children, a Bundy relative Fox was projecting as a regular, when his personal manager and biographer Bernard Jay discovered him dead in his hotel suite, with heart failure the cause.

Bartel’s Out of the Dark (1988) featured him in a last cameo role as a gravelly voiced male detective.

Much of Derek Jarman’s early career was in theatre set design, which was always praised as avant-garde, and as a natural extension of this work he moved into film as a set designer on Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971) and Savage Messiah (1972). The themes of these films – personal sexuality set against a violent religious structure – were to recur throughout Jarman’s own cinematic career, and it was during this period that he began to experiment with his own super 8 shorts.

Jarman’s first feature as director was Sebastiane (1976). Beautifully shot in an almost surreal, sun-drenched setting and spoken entirely in Latin, it’s the story of Sebastiane, a Roman exiled to a men-only outpost in 300 AD. The film establishes themes which characterise all of Jarman’s work – homosexuality, religion and persecution. Slow-motion sequences of naked Roman soldiers cavorting in the sea shocked audiences when it was eventually broadcast on British television (in a late-night spot), and Jarman’s debut feature was greeted with an unparalleled number of complaints about graphic content.

Sebastiane was the first of four films through which Jarman explored gay history. In 1986 he created Caravaggio, the life and death of the last great painter of the Italian Renaissance, openly homosexual, artistically revolutionary and ultimately doomed. This film was followed five years later by a violent reworking of Marlowe’s Edward II (1991), a savage presentation of the treatment of the only openly gay British monarch, and the stark Wittgenstein (1993), a bold, offbeat biography, personalised in Jarman’s unique style to address the politics and sexuality of the great but troubled philosopher. The result was no dry treatise, but a treat for eyes and mind alike.

The Last of England (1987) was the first film made after the director discovered that he was HIV positive earlier in the same year. A pessimistic look at the country he once loved and a personal commentary on England and London under the Thatcher government, there is no linear plot line as such and only one recognisable ‘character’. It’s a mixture of fact and fiction, with Jarman employing arresting images, rock & roll, gay erotica, and his own home movies to create a searing survey of 80s Britain, devastated by greed, violence and environmental disasters.

Jarman followed The Last of England a year later with War Requiem (1989), in which the poetry of Wilfred Owen is employed in a comparison of war with the ravages of AIDS.

In The Garden (1990) the setting moved to the director’s beach house in the shadow of a nuclear power plant. Various images were intercut together – the director, now suffering from AIDS, his curiously beautiful garden, extreme sexuality, the persecution of a gay couple and Catholic iconography. In other words, the world through Jarman’s persona, his own world of dreams.

As mentioned earlier, Wittgenstein (1993) was to be Jarman’s penultimate film, and was infused with the sense of artistic adventure, intelligence and playfulness that characterised his life and work.

Perhaps the most personal of all Jarman’s work came with his last film in 1993. Blue is an unchanging blue screen over which voiceover, music and sound effects give a portrait of Jarman’s battle against AIDS. Composer Simon Fisher Turner wrote the hypnotic soundtrack; actors Nigel Terry, John Quentin and Tilda Swinton read the voice-over. Blue received a simultaneous broadcast on television and radio; at this time the director’s sight was failing and he was shortly to die of an AIDS-complicated illness.

At the New York Film Festival in October 1993, Jarman appeared on stage to introduce his final film. The greeting he received was overwhelming. First he commented on the disease that was killing him: ‘It has destroyed my sight, I couldn’t make another film now because I cannot see enough.’ But there was no room for bitterness. He told a New York Times reporter: ‘You can sit there and feel sorry for yourself or you can get out and attempt to do something. I’ve tried to do the latter.’ Like Andy Warhol, Jarman constantly used the same production base: Brian Eno worked on the scores of Sebastiane and Jubilee, Simon Fisher Turner on Caravaggio, The Last of England, The Garden, Edward II and Blue. Nigel Terry starred as Caravaggio and narrated The Last of England and parts of Blue. Tilda Swinton was Jarman’s most frequent performer, appearing in The Last of England, War Requiem, The Garden, Edward II, Wittgenstein and Blue. Just like Warhol’s body of work, there’s a truly coherent vision running throughout.

Jarman’s influence on contemporary gay culture in Britain cannot be underestimated. An opulent, sensual stylist whose stock-in-trade was the abandon with which he painted his visuals, Jarman’s homosexuality was central to his films. They are gay and proud, and not surprisingly they received screenings on the fourth British television channel when it was trying to establish a contentious modern identity for itself in the 1980s. Channel 4 wanted to be radical and different, so they chose an authentic dissenting voice; and his films certainly offer a genuine alternative to the mainstream. Love him or loathe him, the man was a visionary.

Aristocrat and Marxist, master equally of harsh realism and sublime melodrama, Luchino Visconti was without question one of the greatest film directors of the mid-twentieth century. Immensely rich and a bit of a dilettante, he went to Paris in the 30s to escape the stifling culture of Fascist Italy. In Paris he met, and fell in love with, the fashion photographer Horst P Horst. But even more formative was his meeting with Jean Renoir in the heady political atmosphere of the Popular Front.

After a short stint in the military, Visconti became a designer. Soon he’d befriended Coco Chanel, and by 1937 he was working with the French filmmaker Jean Renoir on Une partie de campagne and was imbued with a lifelong love of cinema. Returning to Italy, he took part in the Resistance and became a convinced Marxist, which he remained until his death.

His first feature, Ossessione (1943), came under fire from Mussolini’s government. An unauthorised – and partly homoeroticised – reworking of James M Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, about a woman who murders her husband, the film angered the authorities with its gritty representation of everyday life, and was severely censored.

Visconti’s political leanings were expressed in his second film La Terra Trema (The Earth Trembles) (1948), which tells the story of class exploitation in a small, Sicilian fishing village. This theme continued with the 1960 film, Rocco e i Suoi Fratelli (Rocco and his Brothers).

As one of the ‘Big Three’ of post-war Italian cinema – along with Fellini and Antonioni – he enjoyed huge creative freedom and was often dubbed a ‘genius’ who made ‘masterpieces’.

In his later work, Visconti seemed to move away from the neorealist style towards more historical and literary themes. The battle between progress and nostalgia is constantly fought in his work, but towards the end of his career Visconti seemed to favour the latter with a definite air of scepticism about the value of progress.

Many of Visconti’s films feature few homosexual characters but many handsome young men. From the 1960s, his films became more personal, focusing on themes of sadness, ageing and death with somewhat of an autobiographical strain emerging, first in The Leopard (1963). Visconti’s lush adaptation of The Leopard, Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s 1958 novel, chronicles the decline of the Sicilian aristocracy during the Risorgimento, a subject close to his own family history.

Another film with an autobiographical strain was Death in Venice (1971). Having undergone various peaks and troughs of popularity, it’s a great film of extraordinary scenes, an inspired soundtrack and a remarkable central performance. The celebrated story of homosexual desire, a man obsessed by ideal beauty, it’s a ravishing piece of cinema. An adaptation of Thomas Mann’s novella, it explores the world of moribund composer Gustav Aschenbach (Bogarde) who, abroad on a rest holiday, glimpses 14-year-old Björn Andresen, who inspires him to give way to a secret passion and question the validity of his entire life.

Earning its maker a Cannes Film Festival Special 25th-Anniversary Prize, Death in Venice – with a soundtrack feast of Gustav Mahler music and a haunting Bogarde performance – is Visconti at his best.

Like Aschenbach, Visconti is an artist obsessed: his films are awash in mood, period detail and emotions which seethe beneath placid surfaces.

Not the easiest of directors (leading lady Clara Calamai called him ‘a medieval lord with a whip’), Visconti nonetheless commanded the greatest respect from his actors. Despite his famed ill treatment of Burt Lancaster on the set of The Leopard, the actor still felt that Visconti was ‘the best director I’ve ever worked with... an actor’s dream’.

Openly bisexual, as was his father, Visconti’s films have few explicitly gay characters, although there is often an undercurrent of homoeroticism. He favoured attractive leading men, such as Alain Delon, and his final obsession was Austrian actor Helmut Berger, whom he directed in The Damned (1969), Ludwig (1972) and Conversation Piece (1974).

His smoking (up to 120 cigarettes a day) led to a stroke and subsequent ill health, but he rallied long enough to make The Innocent (1976) before dying in the same year, at the age of 69, in Rome. Luchino Visconti’s funeral was attended by President Giovanni Leone and Burt Lancaster.

The openly gay, self-proclaimed ‘Prince of Puke’ certainly lives up to his reputation, having provided us with a body of work which encompasses drag queens, rock ‘n’ roll, capital punishment, sexual roles and gender bending. Waters once said: ‘If I see someone vomiting after one of my films, I consider it a standing ovation.’

Growing up in Baltimore in the 50s, Waters was completely obsessed by violence and gore, both real and on the screen. With his weird, counter-culture friends acting, he began making silent 8mm and 16mm films in the mid-60s, which he screened in rented Baltimore church halls to underground audiences drawn by word-of-mouth and street leafleting campaigns. He gathered together interested friends and neighbours to form his own stock company, the undisputed star of which was Harris Glenn Milstead, a former high-school chum and 300-pound cross-dresser who billed himself as Divine.

Success came when Pink Flamingos (1972) – a deliberate exercise in ultra-bad taste made for just $10,000 – took off in 1973; helped no doubt by lead actor Divine’s infamous dog-shit eating scene. He continued to make low-budget shocking movies with his Dreamland repertory company, until he went into partnership with New Line Cinema in 1981 and made Polyester, which had Divine as the heroine Francine Fishpaw, who has a lot on her plate – a slutty daughter (Mary Garlington), a criminally insane son (Ken King) and a cheating porn-king husband (David Samson) who drives her to alcoholism. Although lacking in the harsh edges of his earlier work, Polyester gained Waters his first real mainstream success.

Hollywood crossover success also came with Hairspray in 1988, a surprisingly wholesome slice of early 60s nostalgia starring Ricki Lake as hefty Tracy Turnblad who longs to be on a lily-white local TV dance show. As a result, Universal Pictures noted the resounding success of Hairspray and duly obliged by handing over $8 million to Waters to direct a hipper, funnier variation of Grease. The result was Cry-Baby (1990), starring Johnny Depp alongside his regulars, Mink Stoole, Patty Hearst and ex-porno star Traci Lords.

Obviously, having ‘gone Hollywood’, some changes were made. Not that he actually went to Hollywood, shooting the Depp movie instead in his beloved Baltimore once again. Though the ditching of the grotesque elements associated with Waters’ films was clearly designed to bring his sensibilities to mainstream audiences, his manic energy was still on show.

Waters’ Serial Mom (1994), with Kathleen Turner, was even more glossy, and the Edward Furlong-Christina Ricci comedy Pecker (1998) fairly tame, although it was still set in Baltimore.

Into the new decade, a bit of the vintage Waters crept back in with Cecil B DeMented (2000), which, though not as humorous as the films that built his shock legacy, seemed charged in a way that Waters’ work had not been since the 70s. In the film, a reactionary band of filmmakers, led by a guerrilla director, force a Hollywood actress to star in their low-budget movie.

A Dirty Shame (2004) was another example of him documenting the awakenings of suburban repression, with Tracey Ullman playing a sex-addict housewife who ends up in a local sex cult. The film didn’t skimp on trademark bodily excrement and fluids, proving that Waters hadn’t lost his passion for the deviant flipside of mainstream culture.

In 2006, came This Filthy World, a celluloid representation of Waters’ regular and ever-evolving, filthy-minded solo show, which he’d toured America with for three decades. In Jeff Garlin’s film of the show, the man William S Burroughs called ‘the Pope of Trash’ addresses the crucial issues of the day – from the theory and practice of ‘teabagging’ and the home life of Michael Jackson, to why Charlize Theron didn’t thank Aileen Wuornos in her Oscar acceptance speech, and what it’s like to attend children’s movies alone when you look like a child molester. The 86-minute concert film also includes reminiscences about working with Divine, poppers, swivel chairs and his country’s unheeded cry for an all-voluntary lesbian army: ‘They could find Bin Laden!’ At one point, the great man admits, ‘I was the only kid in the audience who didn’t understand why Dorothy would ever want to go home to that awful black-and-white farm, when she could live with winged monkeys and magic shoes and gay lions…’ Filmed at New York’s hallowed Harry De Jur Playhouse, Garlin’s film was an unforgettable and bizarrely endearing session in the company of one of the world’s greatest and most gleefully original entertainers.

This Filthy World is just a small part of what seems to be a John Waters revival recently. In 2007, his 1988 movie Hairspray enjoyed a Hollywood remake, with John Travolta dragging up to take on Divine’s role of Edna Turnblad, and the stage musical in London’s West End followed soon after. Waters is also said to be planning a Broadway revival of his 1990 Johnny Depp movie Cry-Baby and has another interesting idea in mind too: ‘Pink Flamingos would make a great opera, ‘cos the fat lady sings and eats dog shit at the end. That would work!’

On whether he intentionally makes gay-interest cinema, Waters stated recently: ‘I think they’re funny movies with gay appeal, hopefully, but I never just wanted to ghettoise and say I’m a gay filmmaker. I’m a filmmaker who’s gay. I’m not trying to get out of being gay or anything but I make films for straight people as much as gay people.’