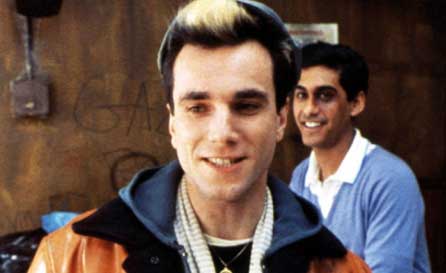

Daniel Day-Lewis as Johnny and Gordon Warnecke as Omar in the British gay classic My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) © Photofest

Daniel Day-Lewis as Johnny and Gordon Warnecke as Omar in the British gay classic My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) © Photofest

It was the decade of dosh, and the 1980s were all about money, consumption, yuppies and greed, not to mention dirty dancing and designer drugs.

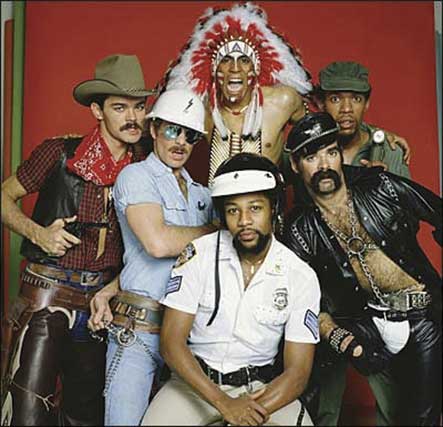

In 1980, to kick the decade off, American cinema dished out two very different gay-interest movies – the Village People disco extravaganza Can’t Stop the Music and the Al Pacino police thriller Cruising. While Can’t Stop the Music bombed at the box office, mainly down to the fact that people had ditched disco for punk or new wave rock, Cruising, on the other hand, attracted much attention. In fact, it caused more controversy than director William Friedkin could ever have imagined.

‘The 70s are dead and gone. The 80s are going to be something wonderfully new and different, and so am I.’

Samantha in Can’t Stop the Music

His film explored the S&M life of New York City with Pacino as an innocent young cop chosen to go underground in search of a killer. After a string of hot encounters with men in Greenwich Village’s seedier gay bars, he starts to question his own sexuality.

‘This isn’t a film about gay life,’ Friedkin stressed. ‘It’s a murder mystery with an aspect of the gay world as background.’

But despite the director trying to play down his film’s lurid depiction of gay life, activists got together anyway for protests outside theatres, in a bid to bury the movie. They felt that Cruising did not show a ‘positive representation’ and was therefore deemed a homophobic distortion. But there is actually something quite distorted about this logic. The truth is that the gay scene, whether it be S&M bars or the commercialised dance-club culture, has always been decadent. Drugs, wild parties, seedy bars, anonymous sex. So Cruising wasn’t all that inaccurate. Gay life isn’t always pretty rainbows, Pride marches and Will & Grace re-runs. In fact, Cruising, when watched now, over 30 years later, is actually quite entertaining and a not-too-unrealistic glimpse into gay life in the pre-AIDS days.

Admittedly, there are homophobic elements to Friedkin’s film, especially in the dialogue uttered by the cops about ‘fags’, but there were far more homophobic movies around in the early 80s. That same year, Gordon Willis directed Windows, in which bad lesbian Elizabeth Ashley stalks good heterosexual Talia Shire. Meanwhile, evil gay men came to foul ends in American Gigolo (1980) and Deathtrap (1982).

‘It’s your music that’s bringing all of these talented boys together. They ought to get down on their knees!’

Helen in Can’t Stop the Music

One film that was certainly more homophobic than Cruising was James Burrows’ 1982 one-joke ‘comedy’ Partners, about two cops – one homosexual (John Hurt), the other one straight (Ryan O‘Neal) – posing as lovers in order to crack a murder case in Los Angeles’ gay community. All the gay characters are raving queens, either prancing around with their limp wrists in the air or swooning as soon as O’Neal enters the room. Hurt, usually dressed in pink or lilac, tries his best to help solve the crime but is, naturally, more content to bake a soufflé or stare doe-eyed at O’Neal as he adoringly serves him breakfast in bed. The film is utterly horrendous and painful to watch, although, interestingly, didn’t seem to attract the same furore as Cruising. Perhaps homophobic filmmaking is more acceptable in comedy than it is in drama.

‘There’s a lot you don’t know about me’

Steve Burns (Al Pacino) in Cruising

Actually, the gay activists who targeted Cruising back in 1980 needn’t have bothered. After all, this was the early 80s when people were already wary of such subject matter, and there were plenty of other activists complaining about the film; no shortage of ‘normal’ suburban types complaining that they didn’t want these kinds of films being shown at their local family movie chains.

As if in answer to the controversy surrounding Cruising’s depiction of gay life, Arthur Hiller made the all-too-well-meaning and rather sickly gay love story Making Love (1982). The story of a married couple forced to confront the husband’s homosexuality when he becomes attached to an openly gay writer, Hiller’s film aimed to present a ‘non-stereotypical’ view of gay men dealing openly and honestly with their sexuality – as opposed to Pacino’s character in Cruising, whose curiosities about muscular men and hard sex all took place in a darker, more promiscuous environment.

Later in 1982, a bigger stride forward seemed to come in the portrayal of lesbian characters. In fact in Personal Best (1982) they were visible in a Hollywood film that refreshingly did not end with self-hatred and suicide. The film depicted a lesbian relationship between two athletes who meet at the Olympic trials. Although the relationship doesn’t last, the main characters, Tory and Chris, are not depicted as abnormal. They are young and attractive women involved in a relationship that lasts over three years. The two women are in no way ashamed of or embarrassed by the set up, and sex scenes develop without either character breaking down in tears or feeling ‘sick’ about themselves.

‘If it feels good, do it. You don’t get any points for playing by the rules.’

Bart in Making Love

A year later, Silkwood (1983) depicted lesbianism as more than simply an adolescent phase. Cher starred as Dolly, Karen Silkwood’s lesbian roommate and best friend. Although the lesbianism wasn’t the central theme of the film, Dolly’s character is highly visible and her relationships are given enough attention to be considered a significant strand of the film. In an early scene that foregrounds Dolly’s lesbianism, her lover emerges from the bedroom one morning. Surprised for a split second, Karen’s live-in lover Drew quickly turns to her and says, ‘Well, personally, I really don’t see anything wrong with it.’ Karen agrees and replies, ‘Nope, neither do I.’

Both Personal Best and Silkwood scored quite well at the box office (Silkwood grossed over $35 million in the United States) and garnered good reviews.

Despite these gains, however, another backlash against homosexuals would soon follow, resulting from one of the key milestones of the 80s – the AIDS epidemic.

Unknown at its beginning, by 1989 the terminology of the disease was familiar wherever English was spoken: HIV, PWA, AZT and so on. The official answer was ‘safe sex’: not an easy concept to popularise at a time when the media were obsessed by ‘bonking’. It also didn’t help that the 1980s were ruled by staunchly right-wing politicians. In Britain, the Conservative Thatcher government had come into office in 1979 and, in 1980, Ronnie Reagan beat Jimmy Carter in a landslide US election.

Despite the discovery of the AIDS virus in 1981 and thousands of cases in the following few years, the Reagan administration remained silent on the issue until after the death of movie star and international icon Rock Hudson from the disease in 1985, by which time there were approximately 8,000 cases. In fact, Reagan did not publicly utter the word ‘AIDS’ during the first six years of his administration and his first public mention of the disease didn’t come until a press conference in which he discussed the federal government’s role in fighting it in May 1987.

The spread of AIDS across the United States brought about widespread public panic and fear back in the UK, much of which, thanks to British tabloid newspapers, was directed at gays as perceived carriers of the virus. Thatcher’s government did little to allay fears or educate people about the reality of the disease, preferring instead to vote in the now-repealed Section 28, which prohibited local councils from promoting materials on homosexuality. This only served to inhibit the teaching of safer sex among young gay men, those with the highest death rate from AIDS infection.

Many believe that it took a movie star’s death to legitimise the need for political action. They are probably right. So, in the early part of the decade, with politicians staying tight-lipped, it was left to filmmakers to get the issue onto the agenda.

Soon after AIDS appeared, an ‘AIDS cinema’ emerged, coinciding with the mid-80s American indie production boom. Films like An Early Frost (1985) and As Is (1986) were typical of this genre, which portrayed the plight of white middle-class gay folk in a somewhat maudlin way as they came to terms with the spread of the new terminal disease. Most AIDS movies made at the height of the epidemic tended to be high-minded dramas awash in mournful, teary-eyed scenes, promoting an image of martyr-like victims that much of the gay community really wanted to ditch.

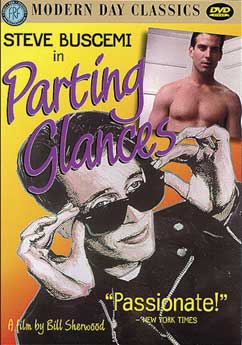

Parting Glances (1986) enjoyed more success and is a better example of entertaining, perceptive independent filmmaking. Director Bill Sherwood’s film concerns a young writer whose present lover is leaving him for a foreign-based job, while his ex-lover Nick (Steve Buscemi) is dying of AIDS. Parting Glances succeeds because the film indulges in no special pleading, merely regarding the disease as another fact of gay life.

The late writer/director Arthur J Bressan Jr made a poignant low-budget drama in Buddies (1985) about a young man who volunteers his spare time as a ‘buddy’ to help care for a dying person with AIDS. Less widely distributed than Parting Glances, Buddies is regarded as the first AIDS feature film. Skilful and moving, Bressan does not forget to include an erotic dimension in his depiction of a community coming together to mourn a loved one’s fade-out.

Away from the United States, European cinema provided two of the best gay-themed films of the 80s. Unlike a rather nervous, twitchy Hollywood, filmmakers in Europe tended to embrace gay subjects and, in 1982, German director Rainer Werner Fassbinder gave us Querelle, a surreal, sweat-drenched adaptation of Jean Genet’s novel about an enigmatic, drug-dealing sailor (Brad Davis) on leave in a seedy seaport. Amidst the sultry, highly charged atmosphere, he embarks on a journey of sexual self-discovery. With its striking iconic imagery, set against the orange glow of a permanent sunset, Fassbinder’s last film was a dreamlike experience and a unique piece of gay cinema.

A few years later, from Spain, came Law of Desire (1987), a deliciously overwrought gay soap opera about a trendy film director yearning to be swept up in all-consuming passion. Part fantasy, part murder mystery, part erotic comedy, it wowed gay audiences with its steamy man-on-man sex scenes and also featured a pre-Hollywood Antonio Banderas. Pedro Almodovar’s film became a hit at the Berlin Film Festival and led to the director being dubbed a ‘Spanish John Waters’.

The British film industry delivered a few hit gay-themed movies in the 80s too. In 1983, adapted by Ronald Harwood from his hit 1980 play, came, arguably, one of the best films ever made about the theatre. The Dresser featured Tom Courtenay as the very camp gay dresser who is infatuated with the ageing, spoiled actor played by Albert Finney. Courtenay is the only person who can handle the crotchety old man whose love of theatre supersedes all other considerations. Both actors are outstanding and, in 1984, both were nominated for an Oscar for Best Actor. Courtenay also won the Best Actor Golden Globe.

Also from the UK, in 1985, came My Beautiful Laundrette. With its multifaceted depiction of a society turbulently struggling with issues of class, race, gender and sexual orientation, Stephen Frears’ film seemed to announce a new departure for both British cinema and gay cinema. Set within the Asian community in London, Hanif Kureishi’s unusual love story concerned itself with identity and entrepreneurial spirit during the Thatcher years and featured an inter-racial gay affair between a white, left-wing punk (Daniel Day-Lewis) and an Asian laundrette manager (Gordon Warnecke).

My Beautiful Laundrette was just one British gay-themed film from the 1980s which seemed to celebrate heroic homosexuals, a stance which would have been unthinkable before 1960 when the subject was almost never mentioned in films. The ultimate outsiders, gay men were shown in a variety of historical eras defying the system, social prejudice and middle-class morality in a string of UK productions: Another Country (1984), An Englishman Abroad (1983), My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), Maurice (1987) Prick Up Your Ears (1987) and We Think the World of You (1988).

‘I’m an unspeakable of the Oscar Wilde sort.’

Maurice in Maurice

British actor Gary Oldman excelled in both of these last two films, but although We Think the World of You was an interesting movie – it had a bisexual Oldman in jail while his lover Alan Bates transferred his affections to Oldman’s dog – it was a peculiar tale, too indifferently made to have much impact. Prick Up Your Ears, on the other hand, was always destined for success, with Oldman playing Joe Orton in Stephen Frears’ follow-up to Laundrette. A powerfully acted film, it traced Orton’s stormy relationship with his lover Kenneth Halliwell, from their college days to the stressful time of Orton’s first success.

Prick Up Your Years was released around the same time as the other hit British gay-themed movie of 1987, Maurice, a superior Merchant Ivory production about gay love across the class divide, starring Hugh Grant, Rupert Graves and Denholm Elliott.

It was quite a brave move for director James Ivory and producer Ismail Merchant to follow up their hit A Room with a View with this less commercially viable EM Forster adaptation, but its success pointed to the fact that gay cinema had, at least in Britain, moved quite a few steps forward.

Most of the internationally distributed British art cinema came about through the advent of Channel 4 funding in the mid-80s. A UK government policy came out in February 1980 stating that ten per cent of the new channel’s budget should be used on regional film funding. These initiatives, together with British Film Institute funding, helped acclaimed British auteur Derek Jarman finance his landmark Caravaggio (1986), a pastiche period biopic based on the life of Italian seventeenth-century painter Michelangelo da Caravaggio. Jarman, working on a minuscule budget, still managed to produce an avant-garde masterpiece.

Another British auteur who achieved notable success in the 80s was the gay Liverpudlian director Terence Davies. Although he’d started work on a trilogy of films back in 1976, the three films were eventually released together in 1984. Taken together, the three films traced the biography of a man over seven decades. In the first part of the trilogy, Children (1976), a young Robert Tucker is victimised at school and deeply attached to his emotionally unstable mother. The second film, Madonna and Child (1980), found Tucker as a middle-aged man, torn by the conflict between his Catholic faith and his gay sexuality. The final film, Death and Transfiguration, depicted Tucker (now played by Wilfrid Brambell, famous from the classic TV comedy show Steptoe and Son) as an 80-year-old man dying in a hospital bed. The trilogy put Davies on the cinematic map as one of the most original British film-makers of the late twentieth century and led to funding for Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988), which had similar, grim subject matter, and a focus on guilt and unfulfilled longing.

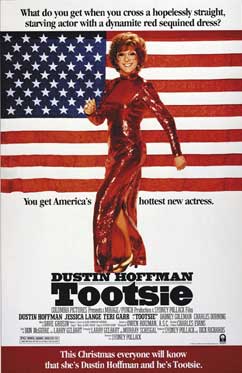

Back in the States, towards the end of the decade, it was also left to indie filmmakers, rather than Hollywood, to carry the torch for gay cinema. Although mainstream American filmmakers were still happy producing comedies with a gay slant, notably Blake Edwards’ transgender farce Victor Victoria (1982) and the Dustin Hoffman drag comedy Tootsie (1982), serious big-budget, studio-produced gay dramas were nowhere to be seen.

Instead, the smaller film company New Line released Paul Bogart’s Torch Song Trilogy (1988), an adaptation of its star Harvey Fierstein’s semi-autobiographical play. The touching story spanned nine years, detailing the life and loves of gay New Yorker Arnold Beckoff, a flamboyant drag queen.

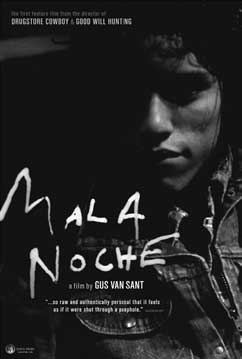

The decade’s best American indie film, however, came from the openly gay director Gus Van Sant. Shot in black and white on a shoestring budget, Mala Noche (1985) was his first feature, a classic tale of doomed love between a gay liquor-store clerk and a Mexican immigrant. The film, which was taken from Portland street-writer Walt Curtis’s semi-autobiographical novella, featured some of the director’s hallmarks, notably an unfulfilled romanticism and a dry sense of the absurd.

Six years later, Van Sant would stay with similar themes for his even more successful hustler movie My Own Private Idaho (1991).

So thanks to the advent of American independent cinema in the 1980s, together with British and European hits, gay and lesbian characters finally became out and proud, and the success of many of these films proved that gay-themed movies could appeal to more than just a niche audience. There was certainly a handful of landmark 80s movies which demonstrated remarkable progress, but it was only in the next decade that the path to understanding and acceptance, at least in the cinema industry, would widen...

US, 123 mins

Director: Nancy Walker

Writers: Bronte Woodard, Allan Carr

Cast: Village People, Valerie Perrine, Bruce Jenner, Steve Guttenberg and Paul Sand

Genre: Musical Comedy

‘Be kind’ – the words of Nancy Walker at an early preview screening of her sole directorial effort Can’t Stop the Music. Perhaps she had realised that disco was all but over by the time this movie was ready for distribution.

After the huge success of Grease, flamboyant producer Allan Carr tried to hit box-office pay dirt again by using the then-popular disco group The Village People, whose worldwide hit ‘YMCA’ had sold more than 10 million records, and whose carefully crafted, macho-satirising image won them a large gay following.

However, by 1980, with the emergence of punk and new wave rock, disco really was on its last legs. Not surprisingly, coupled with the fact that Carr had insisted the film was ‘not gay-themed’, the gay press ended up shunning the movie, especially following one EMI exec’s comment that, ‘A million or two million gay men can make an album a hit, but we have to enlist the “hets” to make a hit of a major picture.’ Arthur Bell dubbed the film, ‘a stupid gay movie for stupid straight people’.

In fact, looking back it is hard to see why the critics gave the film such savage reviews. Was the plot of Can’t Stop the Music really ever important? A New York songwriter Jack Morell (Steve Guttenberg) needs just one big break to get his music heard and land a record deal. So with the help of his retired, supermodel roommate (Valerie Perrine) and an uptight tax attorney (Bruce Jenner – yes that Bruce Jenner), they bring together six singing macho men from the Greenwich Village scene for an outrageous adventure full of fun, fantasy and disco fever. Hardly Shakespeare but then who cares? It features unforgettable dialogue, unimaginable performances and unbelievable production numbers such as ‘YMCA’, ‘Liberation’, a song about milkshakes (draw your own conclusions) and the wonderful grand finale featuring the title song: ‘You Can’t Stop the Music!’

Unfortunately, at the time, critics chose to do just that. Despite its many detractors, however, after three decades the film has begun to find a new audience. As people get nostalgic over 80s culture, the entire movie is being reappraised as pure camp delight, a telling display of how gay culture still managed to celebrate itself under the watchful eyes of 80s conservatives.

The Village People

In fact the movie flows well and is full of charming gay camp, and while the acting isn’t great, the ‘let’s put on a show’ attitude behind it is very sincere. If you manage to find a copy of the latest DVD release, you’ll find yourself laughing rather than cringing all the way until the final, jaw-dropping, gay-studded ending.

US, 106 mins

Director/Writer: William Friedkin

Cast: Al Pacino, Paul Sorvino, Karen Allen, Richard Cox, Don Scardino, Joe Spinell, Jay Acovone, Keith Prentice

Genre: Serial killer thriller

Over three decades after its original release, William Friedkin’s Cruising has transformed from a political issue to an intriguing cultural document.

The 1980 thriller, about a series of murders set against the background of New York’s gay S&M club scene, can be seen as a glimpse of a pre-AIDS gay subculture. Or as an opportunity to see Al Pacino’s naked butt on screen.

Back in late 1979, tempers flared over the White Night Riots, the gay community’s response to the minimal sentence given to former San Francisco City Supervisor, Dan White, for killing George Moscone (then mayor of San Francisco) and Harvey Milk (an openly gay supervisor of San Francisco). So there was a lot of gay anger around and it seems strange that much of it was channelled at the release of Friedkin’s film. Perhaps it was just the wrong film released at the wrong time, but it was seen by much of the gay community as anti-gay.

Al Pacino as undercover cop Steve Burns

Now, though, Cruising can at last be viewed as a piece of filmmaking, one of the most original thrillers of the 1980s. It’s a lurid, twisted film that draws you into its world and completely works you over. It never declares itself to be a movie about ‘gay life’, but rather a murder mystery with an aspect of one part of the gay world as its background.

On the surface, it’s a slasher pic. A killer works his way through the S&M clubs, picking up guys, tying them up and hacking them to death. The killer (Richard Cox) is tall and thin, and wears the regulation sunglasses, chains, biker jacket and hat. Pacino is Steve Burns, a cop who goes undercover to catch the homophobic killer.

But Friedkin’s film is beyond a run-of-the-mill slasher with a strange, one-of-a-kind setting and impassioned direction. The director knows how to make you care and knows how to get you scared. The first killing, presented from the likable victim’s point of view, is agonising to watch. In fact, much of the film involves horrific killings, coupled with seedy thrills – male nudity, simulated fisting and lurid sweaty dancing.

Cruising is a unique thriller in that the main source of interest isn’t in the cop-and-killer angle, but in the hero’s psychological state. It is clear the Pacino character, Burns, is himself sexually frustrated, perhaps even more so than the killer he’s chasing. He uses his wife Nancy as little more than relief. After a night undercover in the gay district he returns to her for a night of hard sex and angrily warns her, ‘Don’t let me lose you.’

The film concludes by shifting back to Pacino for an eerie ambiguous finish: a wonderfully chilling close-up of his reflection staring back at him with strange, cold satisfaction. Was Burns gay? Was he the killer?

US, 113 mins

Director: Arthur Hiller

Cast: Michael Ontkean, Kate Jackson, Harry Hamlin, Wendy Hiller, Arthur Hill, Nancy Olson, John Dukakis, Asher Brauner

Genre: Coming-Out Drama

One of the first Hollywood movies to take a positive look at homosexuality, this domestic drama of a man’s ‘coming out’ presented a non-stereotypical view of same-sex desire.

Michael Ontkean plays Zack Elliot, an LA doctor, married happily (it seems) to fast-rising TV exec Claire (Kate Jackson). But when novelist Bart McGuire (Harry Hamlin) walks into his office, his long-repressed homosexuality comes to the fore. In a move which leaves him wracked with guilt, Zack cancels dinner with his wife in order to go out with Bart. He is inexplicably drawn to this man and embarks on a secret affair with him, although the writer seems intent on keeping him at arms’ distance. Bart is used to having a good time, loves no-strings sex and hates the idea of commitment, so won’t allow their relationship to grow. Exasperated, Zack asks Bart, ‘Do you snore? Does anybody ever get a chance to find out?’

The character of Bart is not a negative portrayal. He’s not a screwed-up gay, just footloose and fancy free, a well-off, self-reliant and confident gay guy who doesn’t need anyone or anything, and likes playing the field. Zack, on the other hand, is used to commitment and wants a stable, romantic, monogamous relationship – a state he has become quite used to during his marriage to loyal, intelligent Claire.

As Zack’s absences become more and more frequent, Claire’s concern manifests itself in the suspicion that he is having an affair with another woman. Jilted by Bart and feeling alone for the first time in his married life, Zack resolves to tell Claire the truth about himself. He knows his marriage is over and so he tells her exactly what’s going on. Predictably, Claire is shocked that she could have known so little about the man she has loved for so many years and accuses him of deceiving her from the very start. With emotional recriminations underway, it’s not long before Claire is tearing her husband’s clothes out of the closet and throwing them on the floor.

Kate Jackson and Michael Ontkean

Making Love was certainly a breakthrough film, the first Hollywood-produced and marketed gay-themed film for a general audience and one of the first American mainstream movies to show two men kissing.

A Scott Berg conceived the story after six of his friends came out after marriage. ‘What the black movement was in the 60s, and the feminist movement in the 70s, the gay movement will be in the 80s,’ he said. Working from Berg’s original concept, his partner, Barry Sandler, penned a fairly absorbing screenplay, utilising elements of classic melodrama to tell a modern love story. Sandler has explained that the script was the direct result of his decision to write from his personal identity and experience.

Director Arthur Hiller, on the whole, elicited strong performances from his actors – Jackson is suitably overwrought, Hamlin exudes sexuality – but Ontkean frequently looks as though he wishes he was elsewhere. Hiller also has the trio directly addressing the audience with their thoughts from time to time, a device which seems to pay off. That said, although Making Love was a brave movie at the time, these days it’s got less power than the average soap opera.

Writing in The Advocate in 2002, recounting how his gay love story somehow got made by a Hollywood studio, Sandler stated: ‘There were hurdles. Hollywood in the Reagan 80s was a conservative, closeted, chickenshit town. Showing gay characters in a positive light – were we crazy? Agents and talent shunned the project, deeming it too risky. But at 20th Century Fox, [producers] Sherry Lansing and Dan Melnick quickly committed, sensing a groundbreaker. A few brave actors stepped up, damn the sceptics, and the movie was made.’

Those few brave actors did not include Harrison Ford, Michael Douglas and Richard Gere – they all turned down the male lead, expressing reservations about the subject matter.

Publicity surrounding the film was exhaustive. Sandler decided to come out publicly as the movie opened, so the studio sent him on a cross-country tour, taking in appearances on huge mainstream US shows – Today, 20/20, and so on. In 2002, he told The Advocate magazine: ‘I was announcing that yes, I was gay, so what? But more important than promoting the film, my reason for these appearances was that I thought if, instead of seeing the sick gay stereotype they were used to, people saw this ordinary guy being open and unashamed about his sexuality, then maybe they’d see there was no shame in it. Neither my body nor my career was harmed, contrary to what I’d been warned.

‘To the gay community this was more than a movie – it was a celluloid insignia that told the world we’re as good as everyone else. When it failed to make a fortune, some declared it the death knell for positive gay-themed movies. Well, it wasn’t; in fact, scores more followed. But we were the first. Someone had to be.’

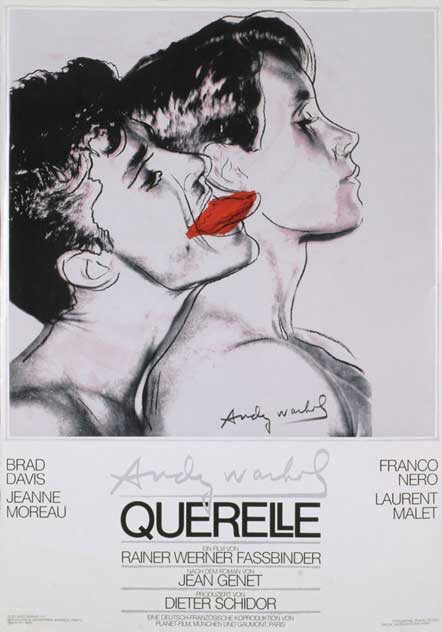

France, 107 mins

Director/Writer: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Cast: Brad Davis, Franco Nero, Jeanne Moreau, Laurent Malet, Hanno Poschl, Gunther Kaufmann, Burkhard Driest

Genre: Sadist drama

Fassbinder is the auteur who contributed more gay representations and instigated more debates on gay male cinematic representations than any other in the 70s. This, his final film, made in 1982, is set in a phallic dreamscape where romance is synonymous with cynicism and brutalism with love.

A sexy, moody hunk of a French sailor called Querelle arrives in Brest and soon starts frequenting a strange bordello. He discovers that his brother Robert is the lover of the lady owner, Lysiane, played by Jeanne Moreau. Here, you can play dice with Nono, Lysiane’s husband: if you win, you are allowed to make love with Lysiane; if you lose, you have to make love with Nono... Querelle is soon mixed up in this strange world and loses on purpose...

No one is more enamoured of Querelle than his own commanding officer, Lieutenant Seblon (Franco Nero), who narrates his lust into a tape recorder and watches Querelle from afar. But Querelle has other plans: he wants to prove himself a criminal mastermind, capable of engineering two perfect murders – that of a fellow sailor and his own execution.

After murdering the sailor, he pins the blame on known homosexual Gil. But when Querelle finds himself in a sexual relationship with Gil, his dangerous circumstance becomes even more complicated.

Based on Jean Genet’s novel, Querelle marked the end of the controversial directorial career of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. The director chose to bow out with a morally disjointed story where legal and sexual standards shift constantly. Fassbinder mocks morality, and himself, even blotting out a plaintive, romantic song by one of the characters with the sounds of a cheap video game. And he certainly doesn’t want the film to be easy to watch – the film is meant as a challenge to its audience, a final act of defiance by a director who certainly had nothing left to lose. In the spirit of this resistance to convention, Fassbinder even shot Querelle in English, as opposed to his native German.

Critically savaged (and possibly misunderstood) upon its 1983 release, Fassbinder’s swansong offers a uniquely surreal and dreamlike tone and a wealth of fascinating imagery to the adventurous viewer, including a hugely erotic scene of anal intercourse that’s still very rare in film. The poster alone is unforgettable, and the movie needs to be seen to be believed.

US, 78 mins

Director/Writer: Gus Van Sant

Cast: Tim Streeter, Doug Cooeyate, Ray Monge, Nyla McCarthy, Sam Downey, Bob Pitchlynn

Genre: Youth Drama

The seeds of Gus Van Sant’s later work My Own Private Idaho (1991) can be seen in Mala Noche, the director’s 1985 debut feature, about a group of Mexican street kids in Portland and the gay bohemian who falls in love with them.

Walt (Tim Streeter) is the lovesick liquor-store worker who is openly gay and lives his life surrounded by the winos and illegal workers of Portland. He becomes infatuated with the manipulative Mexican youth Johnny (Doug Cooeyate) and although he knows he has no chance of developing anything serious with him, he clings on hopelessly. Sixteen-year-old Johnny exploits Walt’s feelings and the pair live on the edge of ruin and have a blast doing it for as long as they can, taking thrill rides in the country and fighting like puppies. But, frustrated by Johnny’s abusive and taunting behaviour, Walt eventually finds consolation with Johnny’s friend, Roberto, another handsome Latino boy.

There are echoes in Mala Noche of Martin Bell’s powerful documentary of the same year, Streetwise, about how homeless kids in Seattle survive by prostitution, panhandling and robbery. An early example of ‘new queer’ cinema, with a brilliant self-effacing script, Van Sant’s film also shares the same bored-youth-punk feel as Alex Cox’s brilliant 1984 genre-buster debut Repo Man. Both are very low-budget declarations of a new vision, inspired by punk rock, although Cox was more overtly referential.

Tim Streeter as Walt

Unlike most low-budget debuts (Van Sant shot it on grainy 16mm black-and-white stock with a tiny budget of $25,000), Mala Noche features some fine understated performances, an interesting script and a good sound mix. It also happens to feature one of the most likable and most realistic gay characters ever to grace the screen.

UK, 90 mins

Director: Stephen Frears

Writer: Hanif Kureishi

Cast: Daniel Day-Lewis, Gordon Warnecke, Saeed Jaffrey, Roshan Seth, Shirley Anne Field

Genre: Racially-mixed gay love story

My Beautiful Laundrette will remind you of those mid-80s days when Thatcherism ruled the earth (or so it seemed) and money was king. Set within the Asian community in London, Stephen Frears’ low-budget adaptation of Hanif Kureishi’s subversively critical play captures the contradictions of that time in a way that’s as fresh today as when it was new.

Omar (Warnecke) is the aspiring capitalist given an opportunity by his uncle Nasser (Jaffrey) to grab a share of Britain’s wealth by ‘squeezing the tits of the system’. The wheeler-dealer Nasser sums it up when he says, ‘In this damn country, which we hate and love, you can get anything you want.’

Nasser sets up Omar (Gordon Warnecke) with a rundown laundrette and the instruction to make it a glittering palace of commercial success, which Omar temporarily does, with the help of his childhood friend (and ex-National Front member) Johnny (Daniel Day-Lewis). But Johnny is confused: his days as a Union Jack-loving thug have not improved his station in life and now he ‘just wants to do some work for a change’.

Gordon Warnecke (right) with Daniel Day-Lewis in My Beautiful Laundrette

Bringing together two such different characters as Omar (Asian, ambitious, for whom success is defined by wealth) and former childhood friend Johnny (white trash, ex-National Front) was utterly inspired. Watching their friendship develop into love, with the ensuing bitterness and misunderstanding that they suffer from friends and family, is very poignant.

My Beautiful Laundrette isn’t, however, an exploration of alternative sexuality. Instead, Kureishi treats his gay couple as he would do any young lovers who have to struggle against insurmountable odds to be together. Each character is rounded and well defined, imbued with depth and complexity, and the central gay relationship is (for its time) remarkably free of guilt and not used as an incendiary plot device.

Omar and Johnny’s romance successfully survives the racial battle between native Britons and Pakistani newcomers, the moral battle between liberalism and conservatism, the intellectual battle between idealism and pragmatic capitalism, and the political battle between Prime Minister Thatcher and the inner-city, working class.

Funny, touching and anger-inducing, Stephen Frears’ movie wears its age lightly and its era proudly. This complex study of race, politics and sexuality has a consistently comic touch, is expertly acted throughout and remains a definitive snapshot of British life in the 1980s.

Interestingly, My Beautiful Laundrette was originally developed for television but given a cinematic release instead. It was the first movie from the Eric Fellner/Tim Bevan powerhouse partnership and their UK company, Working Title Films (Four Weddings and a Funeral/Bridget Jones’s Diary).

US, 105 mins

Director/Writer: Bill Sherwood

Cast: Richard Ganoung, John Bolger, Steve Buscemi, Adam Nathan, Patrick Tull

Genre: AIDS drama

Bill Sherwood’s 1986 film Parting Glances was described by the Seattle Times as ‘the best movie ever made about gays in the United States... you can’t help wondering why most films can’t move this well or look this good’.

Praise indeed, but deservedly so – this funny and unashamedly romantic feature is a triumph for anyone who has ever been in love, straight or gay.

Sherwood’s only feature spends a day with yuppie Manhattan gay couple Robert (Bolger) and Michael (Ganoung) who have been lovers for years. We meet them, however, on the eve of Bolger’s work-enforced departure to Africa. Choosing to bid farewell in the company of their best friends, the pair come to terms with the end of their six-year relationship, a termination skilfully mirrored in an early cinematic portrayal of an AIDS sufferer (their best friend Nick, played with oodles of caustic wit by Buscemi).

It just so happens that punk-rock star Nick is also Michael’s former lover and it is Michael who must encourage him to attend Robert’s going-away party (hosted by The Drew Carey Show’s Kathy Kinney), meanwhile trying to get Robert to stop avoiding Nick.

Sherwood basically follows Michael around town, as he visits a record store, gets pursued by a cute young cashier, has dinner with a married couple, criticises Robert for his callousness, and tries to nursemaid Nick, whose defiance against convention, pity and a couple of bathetic Don Giovanni-inspired nightmares makes him the firm moral centre of the film, rather than a victim.

Sherwood, who died aged 38, from an AIDS-related disease, in 1990, refuses to handle the illness with kid gloves but, as in the rest of the film, informs the subject with humour, intelligence and warmth. He keeps issues unresolved and his characters very much alive, indulging in no special pleading, merely regarding the disease as another fact of gay life.

UK, 93 mins

Director/Writer: Derek Jarman

Cast: Nigel Terry, Sean Bean, Garry Cooper, Spencer Leigh, Tilda Swinton, Michael Gough, Dexter Fletcher

Genre: Biopic

This excessive but imaginative portrait of the Renaissance painter overcomes its tiny budget with ravishing pictorial compositions that seek to convey the essence of Caravaggio’s own striking artwork.

Michelangelo Merisi Caravaggio (1573–1610) was one of the greatest and most controversial painters of the Italian Renaissance. His erotic paintings of naked saints caused much scandal at the time. Derek Jarman struggled for seven years to bring his portrait of the seventeenth-century artist to the screen. The result was well worth the wait, and was greeted with critical acclaim: a freely dramatised portrait of the controversial man and a powerful meditation on sexuality, criminality and art – a new and refreshing take on the usual biopic.

Jarman’s film centres on an imagined love triangle between Caravaggio, his friend and model Ranuccio, and Ranuccio’s low-life partner, Lena. Conjuring some of the artist’s most famous paintings through elaborate and beautifully photographed tableaux vivants, these works are woven into the fabric of the story, providing a starting point for its characters and narrative episodes.

Nigel Terry plays Caravaggio with intense passion, alongside Sean Bean as his rugged lover, Ranuccio, and Tilda Swinton as Lena, his beautiful mistress who comes between the pair. Swinton was to become Jarman’s muse and long-time collaborator.

The film distinctively merges fact, fiction, legend and imagination in a bold and confident approach that will probably leave serious art enthusiasts and casual viewers outraged by the complete disregard for accurate, historical storytelling. Jarman deliberately dabbles in anachronisms – a car, typewriters, passing trains, tuxedoes and pocket calculators are all thrown into the film – making use of a similar revisionist theory to that which Caravaggio applied to his paintings.

Not surprisingly, the director caused a furore in the art world, and generated accusations of everything from irreverence to downright dishonesty regarding the artist’s alleged homosexual and violent impulses. Certainly, Jarman imposes a homosexual interpretation on the proceedings, depicting the artist’s murder of Ranuccio as the result of a lover’s spat. In fact, the murder charge sent Caravaggio into exile, virtually all that is really known about the artist’s life.

Beyond its homoerotic slant, the film can actually be viewed as something of a satire on the shallowness of the burgeoning 80s art scene, of which Jarman was very much a part. Although the film was seven years in preparation, it was only five weeks in production, shot at a disused East London warehouse. The result is something rather special.

Caravaggio is an inventive and unashamedly pretentious work of modern cinema that deserves a wider audience. With a cast of (now) very well-known faces, such as Sean Bean, Tilda Swinton, Michael Gough, Dexter Fletcher and Robbie Coltrane, not to mention some of the most beautiful photography ever committed to film, Jarman’s work represents an impressive, and for the most part enjoyable, combination of art and cinema that is ripe for rediscovery.

UK, 134 mins

Director: James Ivory

Writers: Kit Kesketh-Harvey, James Ivory

Cast: Hugh Grant, James Wilby, Rupert Graves, Denholm Elliott, Simon Callow, Billie Whitelaw, Barry Foster, Judy Parfitt, Phoebe Nicholls, Ben Kingsley

Genre: Period Drama

In his first major starring role, Hugh Grant gives a compelling performance (proof, if you needed it, that he can do more than just bashful) as a young, upper-class Edwardian student torn apart by a love affair with fellow Cambridge student James Wilby.

This adaptation of EM Forster’s controversial novel offers everything we expect from a Merchant Ivory film – beautiful locations, a who’s who of top British actors and an insight into the world of the repressed upper classes. We also get a delicately handled expression of homosexual love and an account of the difficulty of being gay at a time when it was illegal for men to have sex.

Maurice Hall (Wilby) and Clive Durham (Grant) are close friends whose attachment is actually something more. Clive expresses his love for Maurice, but is only looking for an idealised, platonic relationship, whereas the initially reluctant Maurice is after a more sexual communion. Both men, however, are frightened off when their gay friend is arrested and sentenced to six months hard labour. Clive takes refuge in a respectable marriage, while Maurice’s psychiatrist advises fresh air, country walks and the shooting of small animals as a ‘cure’ for his homosexuality.

Fortunately Maurice finds the honesty and strength to face up to his true nature when a man from a completely different social world enters his life: the attractive, young gamekeeper Alec Scudder (Graves). Together the pair take on society’s social and sexual prejudices, and face some pretty tough times. As Lasker-Jones (Kingsley) puts it: ‘England has always been disinclined to accept human nature.’

The director makes much play of how posh Edwardian society struggles to decide which is worse – that Maurice is bedding a man or that he’s bedding a commoner. Watching the film today reassures us that, as bad as things can be nowadays, we’ve come a long way.

It goes almost without saying that the period is evoked wonderfully well, with lots of floppy haired youths lying around Cambridge colleges and English stately homes, and the acting is universally good. Hugh Grant is worryingly convincing as the effete Clive, while Wilby and Graves conspire to make their slightly unbelievable relationship convincing.

Forster’s 1914 novel Maurice hadn’t been published until after his death in 1971 and was the first-ever novel involving a gay romance to have a happy ending. Turning this novel into a film had always been a pet project of producer/director team Ismail Merchant and James Ivory. It was only when they made the film of Forster’s gay story did the media pick up on the fact that Merchant and Ivory weren’t simply filmmaking partners. In 25 years as ‘collaborators in art and in life’, as People magazine commented, it was the first time the media revealed that the pair lived together.

UK, 105 mins

Director: Stephen Frears

Writer: Alan Bennett

Cast: Gary Oldman, Alfred Molina, Vanessa Redgrave, Julie Walters, Richard Wilson, Frances Barber, Wallace Shawn

Genre: Biopic

Stephen Frears’ film Prick Up Your Ears is a celebration of the outrageous playwright Joe Orton (Gary Oldman) and his stormy love affair with Kenneth Halliwell (Alfred Molina) from their college days to the stressful time of Orton’s first success.

Orton was one of the 1960s golden boys, from working-class Leicester lad to national celebrity, from sexual innocent to grinning satyr, from penniless student to icon of Swinging London. He became a star by breaking the rules – sexual and theatrical. But while his plays, including Loot, What the Butler Saw and Entertaining Mr Sloane, were all hugely successful, his private life was sometimes sordid, often farcical, and also ended in tragedy.

Orton and Halliwell met at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. The inarticulate Orton fell for the seemingly sophisticated Halliwell, and for a while the film dwells on Orton’s promiscuity, at a time when homosexuality was still illegal in the UK. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, Orton becomes an overnight success. He pens West End hits and even gets commissioned to write a script for the Beatles.

However, the conclusion is one of tragedy. Frears depicts the lovers’ life in their apartment as totally claustrophobic and, while Orton enjoys his status as a popular playwright, Halliwell is simply his personal assistant, as he defines himself, trying to find a purpose in a life that he considers useless. He never attains success. Joe doesn’t love him and doesn’t have sex with him any more. He cannot share success with Joe. Inevitably, Halliwell gets terribly depressed... and then the tragedy. Halliwell spirals downwards, from Orton’s lover to his bludgeon killer.

Gary Oldman (left) as Joe Orton with lover Kenneth Halliwell (Alfred Molina)

The modern-day framing device has Lahr (Wallace Shawn) researching his book through interviews with Orton’s agent Peggy Ramsay (Vanessa Redgrave), and the diary he wrote, a clever device which ends up drawing a provocative parallel between Orton and Halliwell’s relationship and that of Lahr and his wife (Lindsay Duncan).

With that in mind, at the time of its release, director Stephen Frears commented: ‘Orton and Halliwell’s life together was as natural to them as a more conventional heterosexual life is to others. This is the way it was – no excuses or explanations. But the fact that they were gay is secondary to their story. It’s about marriage, with many of the same problems as any other marriage that goes wrong, except between two men.’

Frears, fresh off the back of the gay-themed My Beautiful Laundrette, manages to balance our sympathies for both the protagonists, while the leads give what may in retrospect look like the standout performances of their careers: Gary Oldman is excellent as Orton, right down to the remarkable resemblance, while Alfred Molina is superb as an amusing and tormented Halliwell.

US, 120 mins

Director: Paul Bogart

Writer: Harvey Fierstein

Cast: Harvey Fierstein, Anne Bancroft, Matthew Broderick, Brian Kerwin, Karen Young, Eddie Castrodad, Charles Pierce

Genre: Autobiographical drama

Gruff-voiced Tony Award-winning actor and playwright Harvey Fierstein recreates his role as the unsinkable, 40-ish, drag queen Arnold Beckoff in this film adaptation of the smash Broadway play Torch Song Trilogy.

Originated as separately staged one-acters, the play, when finally mounted as a unified work in 1982, proved bracing in its frank depiction of gay sex life, both promiscuous and committed.

Personal, funny and poignant, Torch Song Trilogy chronicles Arnold’s search for love, respect and tradition – while looking good in a dress – in a world in which he doesn’t easily fit. In the opening scene we see Arnold in drag as Virginia Hamm (working with Ken Page as Marcia Dimes and Charles Price as Bertha Venation). Away from the drag performances, Arnold is rather gun-shy of romance, though still allows himself to be picked up in a gay bar by Ed (Brian Kerwin), a handsome, straight-acting schoolteacher who openly announces his bisexuality. They become lovers but Ed can’t really accept his own gayness and chooses to marry.

In what is effectively Act Two, Arnold meets Alan (Matthew Broderick), a stunning young model who used to be a hustler and is 15 years his junior. The two are perfectly matched. For Arnold it’s love at first sight, while Alan is actively seeking out Arnold for his human, as opposed to superficial, qualities. They go beyond being partners: they are soulmates.

Act Three, the more conventional of the sections, is given over to Arnold and Alan adopting David, a disadvantaged gay teenager. Then one night Alan heroically attempts to rescue an elderly man who’s been set upon by gay-bashers and ends up fatally beaten by the gang, leaving Arnold to raise David on his own. Arnold’s greatest challenge remains his complicated relationship with his mother (Anne Bancroft), who comes to visit and refuses to see Arnold’s relationship with Alan as being as valid as hers with her own late husband. Although she eventually comes to understand her son more, that he wasn’t simply going through a phase, she leaves as soon as his back’s turned, suggesting she hasn’t yet fully come to terms with him.

Finally, the mixed-up schoolteacher Ed comes to terms with his sexuality, leaves his wife to be with Arnold and they both raise David together.

Torch Song Trilogy was the last major gay-themed film of the 80s and, although it occasionally sinks into bathos, it is nevertheless worthy viewing for the easy-to-love romantic tangles, the smart one-liners and strong performances, especially the hilarious Fierstein.

It certainly took guts to release this cosy gay film in the late 80s. After all, the box-office charts were dominated by macho men Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone. However, at the time of release, back in 1988, Fierstein stated: ‘This is the perfect time to do the film, because it’s all too easy for people to think of gays as a high-risk group and nothing else. I mean, aren’t you a little sick of every time seeing a gay person on-screen with an IV in his arm?’

Fierstein also pointed out: ‘If every gay person in this country went to see it, it’d be the largest-grossing movie ever. We forget how many of us there are...’

Simon Callow is the ever-jovial British actor who’s been lighting up the stage and screen for years, often in roles that highlight his versatility.

Born in London, Callow became infatuated with the great British actor Laurence Olivier who at the time was heavily involved with the Old Vic Theatre. Callow wrote to him and was amazed to get a response. Olivier wrote back, telling the young Callow that if he was interested in acting, he should consider taking a job at the Old Vic’s box office. He did so and in no time at all was appearing in numerous productions over the years.

Callow made his film debut with a supporting role in 1984 in Milos Forman’s Amadeus before Merchant Ivory gave him the substantial role of the Reverend Beebe in A Room with a View (1985) and a strong supporting role as Mr Ducie in their gay-interest drama Maurice, alongside Hugh Grant, in 1987.

Callow turned in a mesmerising performance as the flamboyant Gareth in Four Weddings and a Funeral in 1994. His character’s open, unapologetic relationship with another man (John Hannah) was among the hit film’s highlights, and had few parallels in American movies at the time. It also drew attention to Callow’s status as one of Britain’s openly gay actors, which also had regrettably few parallels across the Atlantic.

Callow was hilarious as the convener of a men’s therapy group in Rose Troche’s gay-themed comedy Bedrooms and Hallways and as the dour Master of the Revels in John Madden’s Shakespeare in Love (1998). He has also appeared in various American films (even StreetFighter and Ace Ventura), directed a film, Ballad of the Sad Café, written biographies of Charles Laughton, Orson Welles and agent Peggy Ramsay, an intriguing autobiography, Being an Actor (1984), and continued to work on stage, mainly in the UK.

Keeping busy into the new millennium, one of Callow’s most notable appearances was among the ensemble cast of Mike Nichols’ critically acclaimed HBO mini-series Angels in America (2003), a political epic about the AIDS crisis during the mid-80s.

One of the finest, most individual talents the British cinema has produced, Terence Davies has directed films both in the UK (Trilogy, 1984, The Long Day Closes, 1992) and in the States (The House of Mirth, 2000).

Davies’s Trilogy is divided into Children (1976), Madonna and Child (1980), and Death and Transfiguration (1983), each segment telling the life of Robert Tucker – his birth and formative years in school, his father’s death’s impact on him, his closeted homosexuality, still living at home with his daunting mother, and finally his mother’s death and his own impending doom.

In his first full-length feature, Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988), Davies conjured intimate family memories in free-form images, sometimes bleak and brutal, at others tender and nostalgic. His film was a strikingly intimate portrait of working-class life in 1940s and 1950s Liverpool and focused on the real-life experiences of his mother, sisters and brother, whose lives are thwarted by their brutal, sadistic father (a chilling performance by Pete Postlethwaite). Davies used the traditional family gatherings of births, marriages and deaths to paint a lyrical portrait of family life – of love, grief, and the highs and lows of being human.

Distant Voices, Still Lives was recently revived by the British Film Institute, touring the UK again at prestigious festivals. It was also released in a special edition DVD format.

Filmed mostly on location in a grey and rainy Liverpool, The Long Day Closes (1992) was another personal portrait, this time of ‘Bud’, a friendless, probably gay, 11-year-old boy growing up in an ordinary working class Catholic family in Kensington Street, L5 (a street that no longer exists). Set in the early 1950s, Bud, isolated from everyone but his loving sisters and mother, lives for the pictures – the cinema – and in particular for the colour and life of the Hollywood musicals. A truly beautiful film, The Long Day Closes is considered by many to be the director’s masterpiece.

Davies has also proved he can move beyond personal material with two adaptations: of John Kennedy Toole’s The Neon Bible (1995) and Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth (2000). Both had good reviews, but failed to establish his commercial credentials.

Recently, Davies has been trying to obtain finance for a new script: Mad About the Boy, which he describes as ‘a ménage à trois set in the fashion world in London and Paris: a contemporary romantic comedy, in colour and with a happy ending’.

Davies was once quoted as saying: ‘I don’t like being gay. It has ruined my life. I am celibate, although I think I would have been celibate even if I was straight because I’m not good-looking; why would anyone be interested in me? And nobody has been. Work was my substitute.’

Brad Davis was both ruggedly handsome and amazingly versatile, a male lead who made his compelling film debut as an American drug smuggler incarcerated in a Turkish prison in Alan Parker’s Midnight Express (1978).

Davis’s relatively sparse screen roles include off-beat classics such as American Olympic runner Jackson Scholz in Chariots of Fire (1981); the title character – a gay sailor – in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Querelle (1982); and his only comedic role as the eccentric pilot in Percy Adlon’s Rosalie Goes Shopping (1989).

A risk-taking stage actor, Davis won acclaim as Ned Weeks, alter ego of playwright and Gay Men’s Health Crisis-founder Larry Kramer, in Kramer’s harrowing AIDS drama The Normal Heart (1985). He also starred in Steven Berkoff’s avant-garde adaptation of Kafka’s Metamorphosis at the Mark Taper Forum.

Davis’s reputation for bad behaviour both on and off set meant that good parts were rarely offered to him and his roles in Midnight Express and Querelle remain the only ones for which he is remembered. His friend, Larry Kramer, stated: ‘He was one of the first straight actors with the guts to play gay roles.’

Davis contracted the AIDS virus in 1985 but hid the fact from Hollywood execs in order to keep working. In the last few years of his life the actor became a committed AIDS activist, speaking out about Ronald Reagan’s policies and describing the American president as ‘an unbelievably ignorant, arrogant, bigoted person’. Davis continued: ‘How could he possibly think that his opinion on homosexuality had anything to do with a devastating disease that was ravaging people, reducing them to skeletons and killing them.’

The actor, who had been suffering with complications from AIDS, reportedly committed suicide at age 41, not before leaving a handwritten statement blasting Hollywood homophobia: ‘I make my living in an industry which professes to care very much about the fight against AIDS, that gives umpteen benefits and charity affairs. But in actual fact, if an actor is even rumoured to be HIV-positive, he gets no support on an individual basis – he does not work.’

His widow, Susan Bluestein Davis, who continues with Davis’s activist work, is the author of the only published biography of her husband. Worth reading, it gives a fascinating insight into a hugely complex character, although readers will be left feeling that she probably knew her husband rather less well than many of the others in his life.

Dubbed the new Cary Grant in the 80s, British actor Rupert Everett was born in Norfolk, England. Educated by Benedictine monks at Ampleforth College, he dropped out of school and ran off to London to become an actor. In order to support himself, he worked as a rent boy, something he admitted to US Magazine in 1997.

His breakthrough was in the 1982 West End production of Another Country, playing a gay schoolboy opposite Kenneth Branagh, followed by a film version with Colin Firth two years later.

Everett came out as gay in 1989, which many agreed harmed his career for a few years; the movies he appeared in around this time, such as The Comfort of Strangers (1990), had little success.

His comeback came with My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997) in which Everett almost single-handedly conquered Hollywood with his turn as Julia Roberts’ gay friend. As the handsome, elegant and gay George, Everett ushered in a different kind of gay sensibility in Hollywood, one that, rather than begging audiences for acceptance, simply told them to get over it.

In the following year, in Shakespeare in Love, Everett had a supporting role as playwright Christopher Marlowe, and in B. Monkey, in which he played Jonathan Rhys Meyers’ criminal lover. 1999 proved to be an even more fruitful year and he featured in leading roles in four mainstream films. He first played Oberon in Michael Hoffman’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with an all-star cast including Michelle Pfeiffer, Kevin Kline, Christian Bale and Calista Flockhart. Next came the role of Madonna’s gay best friend in The Next Best Thing, followed by Oliver Parker’s adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s An Ideal Husband, for which Everett garnered positive reviews in his central role as the delightfully idle Lord Goring. Finally, he camped and vamped it up as the resident villain of Inspector Gadget, once again demonstrating to audiences why it could feel so good to be so bad.

While Everett will always be dubbed Hollywood’s Gay Prince, he has certainly proved that his roles aren’t simply limited to gay ones – in fact, in recent years, most of his work has been in high-profile movies, playing heterosexual leads.

Fassbinder is probably the best-known director of the New German Cinema. He’s also been called the most important filmmaker of the post-WWII generation. Exceptionally versatile and prolific, he directed over 40 films between 1969 and 1982; in addition, he wrote most of his scripts, produced and edited many of his films, and wrote plays and songs, as well as acting on stage, in his own films and in the films of others. Although he worked in a variety of genres – the gangster film, comedy, science fiction, literary adaptations – most of his stories employed elements of Hollywood melodrama from the 1950s, overlaid with social criticism and avant-garde techniques.

Fassbinder was always a rebel, even declaring his homosexuality to his shocked father at the early age of 15. In his early to late teens, when he wasn’t watching Hollywood movies, he was frequenting gay bars.

He made various films of interest to a gay and lesbian audience, including The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972), adapted from his play. The title character is a dress designer whose heterosexual marriage fails as she falls for Karin (Hanna Schygulla), a beautiful working-class model. Meanwhile, in Fox and His Friends (1975), a queeny older gent destroys a sweet but unsophisticated working-class homosexual, fleecing his lottery winnings and trying to mould him into a more sophisticated type.

Fassbinder’s best-known work Querelle (1982), about a sailor (Brad Davis) anchored in Brest, is a surreal look at a young man discovering his sexuality. Based on Jean Genet’s novel Querelle de Brest, the film deals with various forms of sexuality and love. By the time he made this – his last film – heavy doses of drugs and alcohol had apparently become necessary to sustain his unrelenting work habits. When Fassbinder was found dead in a Munich apartment on 10 June 1982, the cause of death was reported as heart failure resulting from interaction between sleeping pills and cocaine. The script for his next film, Rosa Luxemburg, was found next to him. He had wanted Romy Schneider to play the lead.

Actor/playwright Harvey Fierstein made his off-Broadway debut in Andy Warhol’s Pork at the famed La Mama. He soon began writing about his early experiences (he came out at the age of 13) and, in 1982, Fierstein wrote and starred in the stage play Torch Song Trilogy, a bittersweet three-part comedy concerning the homosexual experience in the AIDS era. The play won two Tony Awards and became one of the longest-running Broadway productions in history, totting up 1,222 performances. Fierstein repeated his stage characterisation of Arnold Beckoff for the heavily rewritten and severely shortened 1988 movie version of Torch Song Trilogy, the essence of which was still autobiographical, since he began performing as a drag queen in Manhattan clubs as early as age 15.

The actor’s crossover performances in mainstream roles have often been quite successful, notably his appearance as the likable cosmetician brother of Robin Williams in Mrs Doubtfire (1993).

Outspokenly homosexual, Fierstein has successfully smashed previous ‘gay’ stereotypes with his deep, ratchety voice and his engaging ‘You got a problem with that?’ belligerence.

However, since his successes of the late 80s and early 90s, Fierstein’s career seems to have been put on permanent hold, due to a mixture of bad choices and bad luck. In 1994, he co-starred in the dreadful, short-lived Dudley Moore TV series Daddies’ Girls, unfortunately lapsing into some of the clichéd gay mannerisms he had managed to avoid in most of his previous work. More recently, Fierstein has stuck to TV projects or voiceover work.