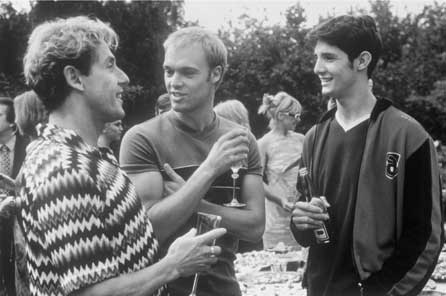

Cocks in frocks on a rock: Guy Pearce, Terence Stamp and Hugo Weaving as we’d never seen them before © Photofest

Cocks in frocks on a rock: Guy Pearce, Terence Stamp and Hugo Weaving as we’d never seen them before © Photofest

Remember the 1990s? Dotcom booms, Desert Storm and presidential impeachment. It’s an era that’s oh-so-close, yet already so far away – the decade of Forrest Gump, grunge and Gay Pride.

‘Just what this country needs: a cock in a frock on a rock.’

Bernadette in Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert

But in the world of gay movies it was the decade of drag and quirky camp comedies, a response to all the AIDS-based dramas of the 80s. Certainly, the early 90s threw up the major work in the AIDS cinema genre, Philadelphia (1993), but the bulk of the decade was made up of outrageous queens and gorgeous leading men with gym-toned bodies in heart-on-the-sleeve films that reassured us there was life after AIDS...

Before gay filmmakers began playing it for laughs though, in the early part of the decade, independent cinema was electrified by a further bumper crop of ‘serious’ gay-themed films which emerged from the more politically minded gay filmmakers of the late 80s: Tom Kalin’s Swoon (a 1992 retelling of the Leopold and Loeb murders), Christopher Munch’s 1991 release The Hours and Times, a fictionalised account of John Lennon and Brian Epstein’s 1963 Spanish holiday together; Richard Glatzer’s Grief (1993), set in the world of trash TV, and Todd Verow‘s Frisk (1995), about the exploits of a gay serial killer set in an erotic world of sado-masochism.

‘Why don’t you light your tampon and blow your box apart, because it’s the only bang you’ll ever get, sweetheart!’

Bernadette in Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert

Dubbed the ‘new queer cinema’ by renowned critic and feminist academic B Ruby Rich, the most successful example of these films was Todd Haynes’ feature debut, Poison (1991), one of the most original American films in years.

None of the American ‘new queer’ films, however, made much of a dent at the box office, with the exception of Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho, one indie release which really smelt like new queer spirit. A worldwide hit, mainly due to the presence of the two lead actors, River Phoenix and Keanu Reeves, it is still remembered for producing some of the most iconic images in gay cinema.

‘Why, you wouldn’t even look at a clock unless hours were lines of coke, dials looked like the signs of gay bars, or time itself was a fair hustler in black leather.’

Scott in My Own Private Idaho

Following on from its success, My Own Private Idaho seemed to become the parent of various indie, gay hustler films during the 1990s. Successfully strutting down the same celluloid street came Scott Silver’s astonishing 1996 directorial and screenplay debut, Johns, set on a hot Christmas Eve in Los Angeles. In Johns, life on the game consisted of violence, theft and sick clients, and like My Own Private Idaho, the film examined friendship between prostitutes. Although writer/director Scott Silver had been working on Johns since 1992, Bruce LaBruce got in a few months earlier with the release of his film Hustler White, which owed just as much to My Own Private Idaho.

‘I’m a connoisseur of roads. I’ve been tasting roads my whole life. This road will never end. It probably goes all around the world.’

Mike in My Own Private Idaho

Even German gay cinema had a 90s entry in the hustler genre with Lola und Bilidikid (E Kutlug Ataman 1999), set in Berlin’s Turkish gay scene, and centring on an enclave of Turks living there as drag queens and hustlers.

Many of the new queer movies coming out of America during the 90s were concentrating on AIDS storylines, such as Richard Glatzer’s Grief (1993). Other new queer efforts dealing with AIDS included Gregg Araki’s HIV-positive road movie The Living End (1992), John Greyson’s outrageous and satiric AIDS musical Zero Patience (1993) and Norman Rene’s Longtime Companion (1990), an absorbing account detailing the effects of the disease on the American gay community through the 1980s, as seen through the eyes of two friends who watch their social circle die around them.

Having ravaged millions of both sexes, including children, especially in Africa, AIDS was still seen in the West predominantly as a gay disease. What had begun as a health crisis quickly became a social crisis, with a steep rise in homophobia and discrimination. So it was a substantial, if calculated, risk for a major movie studio to finance the expensive 1993 mainstream film Philadelphia, Hollywood’s attempt to deal with AIDS.

Immediately following Philadelphia came the much-hyped movie version of Randy Shilts’ controversial best-selling novel about the rise of the AIDS epidemic, And the Band Played On (1993), which many preferred because it wasn’t steeped in the sort of homo-ignorance that had undermined the Hanks movie.

Back in Britain, the early 90s produced some great gay-related movies, most notably Neil Jordan’s unpredictable, unconventional, multi-Oscar nominated masterpiece, The Crying Game (1992), a sleeper hit that took America by storm.

In 1997 came Brian Gilbert’s elegant account of the nineteenth-century playwright Oscar Wilde’s fall from grace, with Stephen Fry perfectly cast as the flamboyant poet whose scandalous affair with a young aristocrat (Jude Law) enraged Victorian society.

Interestingly, a couple of years before Fry appeared as Oscar Wilde, a little British movie called A Man of No Importance (1994) had Albert Finney giving a sublime performance as Alfie Byrne, a bus conductor in 1960s Dublin who comes to terms with his homosexuality through an abiding love of Wilde, entertaining his passengers with the great man’s poems.

More British-produced, gay-interest drama came in the form of Antonia Bird’s melodramatic but still important Priest (1994), starring Linus Roache in an allegory-packed story written by the acclaimed TV writer Jimmy McGovern (Cracker). Wickedly sardonic and very moving, Priest explored a provocative checklist of religious taboos – celibacy, incest, sexual abuse and, of course, homosexuality.

Sean Mathias’s harrowing concentration camp-set Bent was also released to great acclaim, in 1997. A powerful and moving film adaptation of Martin Sherman’s award-winning stage play about three homosexual men’s fight for survival in the face of persecution, it stunned audiences around the world.

Clive Owen, star of Sean Mathias’ Bent (1997)

A lot of the British gay-themed films were comedies: Hettie MacDonald’s coming-of-age drama Beautiful Thing (1996); Neil Hunter and Tom Hunsinger’s fabulous date movie Boyfriends (1996); Paul Oremland’s campy look at the Soho scene Like It Is (1998); and Simon Shore’s youth-led Get Real (1998).

Michael Urwin, Andrew Abelson and Darren Petrucci in Boyfriends (1996)

Meanwhile, over in Eastern Europe during the mid-90s, Czech Republic director Wiktor Grodecki was making a name for himself documenting the stories of real hustlers. His first two documentaries – Not Angels But Angels (1994) and Body Without Soul (1996) – detailed the fast yet fragile lives of teenage male prostitutes in the Czech Republic, following the Velvet Revolution. In both, the youths range in age from 14 to 19 and all hustle at the central train station and at clubs. They talk about why they hustle, what they really think about their clients (mainly foreign tourists), prices, dangers, their thoughts on AIDS, their fears (disease and loneliness), and how they imagine their futures. One Czech bar hustler explains in Not Angels: ‘I think I am like body without soul... The body I sell but my soul is for someone else. My soul is the second me. I want to hustle and I’m not afraid my body will get infected... I want the money. The body has to sell itself but no one can sell the soul.’

‘You know, pumpkins, sometimes it just takes a fairy.’

Vida Boheme in To Wong Foo

Unsentimental and direct, the documentaries gave a real insight into the dark side of the tourist trade, a subject developed further later on in the decade, in Grodecki’s compelling dramatisation of these two films, Mandragora (1997).

‘When a gay man has way too much fashion sense for a single gender, he is a drag queen.’

Noxeema in To Wong Foo

In the mid-90s, there was a noticeable shift in subject matter for gay filmmakers. Following on from the AIDS dramas and new queer movement, and in some ways an answer to it, gay cinema took a comedic turn for the rest of the decade, starting with a brief obsession with drag.

An aspect of gay culture previously seen in movies such as Some Like It Hot and Tootsie, drag was suddenly embraced by mainstream culture again with the 1994 release of Stephan Elliott’s The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, and a year later with Hollywood’s Priscilla rip-off To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar (1995).

‘I’m the Latina Marilyn Monroe. I’ve got more legs than a bucket of chicken!’

Chi-Chi in To Wong Foo

After the release of Priscilla and To Wong Foo came The Birdcage (1996), Mike Nichols’ slick update of La Cage aux Folles (1978), in which Robin Williams starred as the outlandish owner of a wild Miami Beach nightclub where his partner Albert, played by openly gay actor Nathan Lane, is the star attraction.

Aimed straight at the same Middle America targeted by To Wong Foo, The Birdcage was actually a bit better than that; by updating the setting of La Cage to Miami Beach, Nichols energised the film. Meanwhile, the performances – particularly the supporting roles – made The Birdcage genuinely entertaining.

Priscilla, To Wong Foo and The Birdcage – drag had truly been embraced by mainstream culture. And even before these three hits, remember that Robin Williams had already donned drag for much of his 1993 feel-good family comedy, Mrs Doubtfire – and was nominated for an Oscar for it.

More silver-screen gender benders came our way later in the 90s: Todd Haynes’ controversial and explicit Velvet Goldmine took us on a journey into rock ‘n’ roll excess, back to the glam era of the stardust 70s where anything goes; even Clint Eastwood was getting in on the drag act with his movie Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1997), in which the highlight of the piece was a black transvestite called Lady Chablis who rose above all the Dixie prejudice with lines like ‘If your husband’s a gyno, honey, he’s all mine!’

As well as the American and British gay films of the decade, from the mid-to-late 90s, there was a veritable explosion of international productions that attracted attention.

Scenes from Mel Chionglo’s Midnight Dancers (1994)

From Taiwan came Ang Lee’s The Wedding Banquet (1993), which won the Berlin Film Festival’s top prize and succeeded in bringing gay-relationship issues to a mainstream audience.

Meanwhile, from the Philippines came Mel Chionglo’s erotic and shocking Midnight Dancers (1994). Banned in its native country, it told the story of three brothers who work as exotic dancers and prostitutes in a Manila gay club.

China’s entry in 90s gay cinema came from Zhang Yuan whose East Palace, West Palace (1996), about one long night in the life of a young gay writer (Si Han), made the official selection at Cannes.

Another critics’ choice at the 1996 Cannes Film Festival was Hamam: The Turkish Bath, the first film from Ferzan Ozpetek, director of Le Fate ignoranti. An erotic drama, set in Istanbul, Hamam centred on a young Italian designer who inherits his aunt’s Turkish steam bath, and, after becoming infatuated with the young son of the bath’s caretaker, begins questioning everything about himself.

Turks lined up for blocks to see Hamam and it was even nominated to represent Turkey at the 1998 Academy Awards. But the film never had its night in Hollywood. Turkey’s Culture Ministry overruled the independent film board, instead choosing a heterosexual romantic drama as the country’s candidate for the Oscar for Best Foreign Film.

‘Being a man one day and a woman the next is not an easy thing.’

Bernadette in Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert

Meanwhile, during the same year, the official Academy Awards Best Foreign Film entry for Greece also happened to be gay themed. Like a Greek version of My Own Private Idaho, Constantine Giannaris’ From the Edge of the City (1998) took us to a little-known corner of Eastern European chaos: the sad lives of Athens’ immigrant rent boys.

Canada’s best 90s gay movie offering came in John Greyson’s stylish and engrossing Lilies (1996). A complex adaptation of Michel Marc Bouchard’s play Les Fleurette, Lilies was an emotionally intense, suspense-laden tale of love, betrayal and revenge set in the early 50s. It won four Canadian Genie Awards (the equivalent of the American Oscars) including Best Picture, and won critical acclaim worldwide.

Lilies (1996)

Germany, meanwhile, decided to ditch gay drama in the 90s, opting instead for some light-hearted gay-themed movies. Regular Guys (1996) took a tongue-in-cheek look at the complexities of relationships – gay, straight and somewhere in between – while The Trio (1998) had a father-and-daughter pickpocket team opening their arms, and hearts, to a young bisexual drifter, bringing him into their operations.

France also produced a few notable gay movies in the late 90s. A Toute Vitesse (1996) was a poignant study of a group of young French provincials – some from North Africa – falling in and out with one another; Man is a Woman (1998) had Eurotrash presenter Antoine de Caunes as a gay man living in Paris, deciding whether to take his uncle’s bribe to get married, produce children and continue the family name; and Drôle de Felix (2000) centred around a 30-year-old HIV-positive gay man living in a small town in northern France, who decides to take a hitch-hiking trip to Marseilles to track down the father who abandoned him before he was born.

All these international, gay-interest films were well received in their native countries but, more importantly, also garnered some great reviews around the world.

The 90s was also a great period for the girls as well as the guys. At the start of the decade, many lesbians took the Hollywood-mainstream, female-buddy movie Thelma & Louise (1991) to their hearts, because Ridley Scott’s ‘pro-women movie’ made it fairly clear viewers could look beneath the surface of the women’s bonding. The film depicted female friendship and lesbian relationships but left those erotic feelings implicit. Lesbianism remained unspoken, although it’s certainly a source of strength and inspiration.

‘Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask and he’ll tell you the truth.’

Brian in Velvet Goldmine

Thelma & Louise charted the extraordinary tale of a housewife and a waitress (Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis) whose innocent weekend escape becomes an electrifying odyssey of self-discovery. The perfect casting of Sarandon and Davis made Thelma & Louise a movie for the ages, and Brad Pitt became an overnight star after his appearance as the con-artist cowboy.

Many lesbians ‘read between the lines’ as they watched Thelma’s transformation from ultra-femme to ultra-butch. In the closing moments of the film, the lesbian attraction between Louise and Thelma was finally expressed in a kiss on the mouth just before the leap to their death into the Grand Canyon.

Other films, such as Aliens (1986) and Fried Green Tomatoes (1991), also developed strong lesbian cult followings because they too left the sexuality of their female protagonists unmarked, available for lesbian appropriation.

The Hollywood blockbuster Basic Instinct (1992), however, with its lethal bisexuals and ice-pick murders, caused controversy amongst the lesbian community, for the very same reasons that earlier killer-lesbian films such as Russ Meyer’s Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill! had offended.

Paul Verhoeven’s film was criticised for its stereotypes of man-hating lesbians and protesters cried ‘misogyny’ outside cinemas on its opening weekend. They felt it portrayed bisexuals as insatiable, untrustworthy and homicidal.

Equally furious was the response to the hit thriller The Silence of the Lambs (1991), directed by Jonathan Demme and written by Ted Tally, which equated homosexuality and transgenderism with insanity and murder.

Gina Gershon in the Wachowski Brothers’ Bound (1996)

Outspoken lesbian writer/activist Camille Paglia, however, has not only defended Basic Instinct, but called it her ‘favourite film’, even providing an audio commentary track on the DVD release. In fact, in the years since Basic Instinct’s release, many critics have re-evaluated the film. The lesbian film writer Judith Halberstam has noted how Catherine Trammell is quite the lipstick lesbian in control: ‘I would rather see lesbians depicted as outlaws and destroyers than cosy, feminine, domestic, tame lovers.’

Jennifer Tilly in the Wachowski Brothers’ Bound (1996)

In 1996, the Wachowski Brothers (the men behind The Matrix) released their thriller Bound featuring Jennifer Tilly and Gina Gershon as partners in crime – and as lovers. A modern-day film noir, the plot centred around two lesbian ex-cons’ plot to steal $2 million of Mafia money. Simultaneously violent, funny and suspenseful, Bound was placed on many critics’ top-ten lists for 1996.

Another cutting-edge, lesbian-themed movie, High Art (1998), appeared two years later, starring the former Brat Packer Ally Sheedy, whose performance as Lucy Berliner, an enigmatic lesbian, drug-taking photographer won the Best Actress award at Cannes and some of the best reviews of her entire career. High Art was painful and thought provoking, a sincere love story, as well as being a reflection on the nature of art. Above all it was a ‘lesbian film’ for which the lesbianism was integral but not part of an overriding agenda.

Trisha Todd as Claire Jabrowski in Nicole Conn’s Claire of the Moon (1992)

Later, in 1999, from lesbian filmmaker Kimberly Peirce, came the even more successful Boys Don’t Cry, a film based on true events about the life of Teena Brandon. Hilary Swank’s audacious and riveting performance shocked critics for the amount of raw emotion she brought to the character, a lesbian who transforms herself into a man under the name Brandon Teena, in order to gain acceptance in conservative rural Nebraska.

The film earned acclaim from mainstream and lesbian and gay critics, and Swank won both the Golden Globe and the Academy Award for Best Actress. Aside from these mainstream Hollywood forays into lesbiana, ‘real’ lesbian film also caught fire in the 1990s – Claire of the Moon (1992), Go Fish (1994), Bar Girls (1994) and Everything Relative (1996), to name just a few.

And, as lesbian cinema hit new heights, the comedian Ellen DeGeneres came out on her hugely popular TV show in April 1997. This led to a TIME magazine cover, and a wonderfully public relationship with actress Anne Heche. Both became outspoken activists, earning heaps of praise from the community and opening a lot of minds in the process.

In 1998, Will & Grace aired on US television and quickly became the most popular gay-themed network TV series since DeGeneres’ Ellen. A landmark show which attracted worldwide mainstream attention, many episodes were, however, full of campness (Jack in particular) and predictable white-yuppie characters. In fact, it’s fair to say that the huge success of Will & Grace paved the way for a glut of trashy gay comedies into the late 90s and 2000s – but not just on TV.

FERGUS:

‘The thing is, Dil, you’re not a girl.’

DIL:

‘Details, baby. Details.’

from The Crying Game

It’s ironic that the widespread acceptance of homosexuality, thanks to TV shows like Will & Grace, was actually, in some ways, detrimental to the quality of output found in late-90s gay film. Whereas Russell T Davies’s groundbreaking British TV series Queer as Folk was rightly lauded for tearing up the TV rulebook and opening up the world’s eyes to realistic gay culture, most other gay telly shows relied on gay stereotypes and trivialised gay romance. The media-friendly, camp stereotype propagated by Graham Norton, Will & Grace and later Queer Eye for the Straight Guy encouraged others to emulate this gay male figure and, by the end of the decade, there was a whole spate of light and fluffy gay comedy movies – such as Billy’s Hollywood Screen Kiss (1998) and Trick (1999).

In Billy’s Hollywood Screen Kiss, Billy announces at the outset, ‘My name is Billy, and I am a homosexual.’ He says he grew up in Indiana and now lives in Los Angeles, where he rooms platonically with a gal-pal named George. Billy is a struggling photographer who falls in love with Gabriel, a waiter and aspiring musician. Gabriel is probably straight but possibly gay or at least curious. With that in mind, Billy tries to get Gabriel to model for his latest project, while also trying to win his affections. Gripping stuff!

‘It’s only love. What’s everyone so scared of?’

Steven in Get Real

Meanwhile, in Trick, a variety of characters graced the screen – a selfish roommate, an irritating best friend, and a vicious, jealous drag queen, all of whom Gabriel, an aspiring writer, and Mark, a muscled stripper, had to contend with in their quest to find somewhere to be alone for the night. If you get a feeling you’ve seen it all before, it’s because you have.

All fairly non-threatening, these films, in fact, were no more than extended versions of safe mainstream TV sitcom episodes. Even the New York Post dubbed Rose Troche’s bland gay romp Bedrooms and Hallways (1999), ‘Friends meets Almodovar!’ while Village Voice exclaimed, ‘It’s a gay-friendly Friends!’

Kevin McKidd (Leo), Jennifer Ehle (Sally) and Tom Hollander (Darren) in a scene from Rose Troche’s Bedrooms and Hallways (1999)

Other offenders included Broadway Damage, I Think I Do and In & Out, all released in 1997. The main problem with these cute-boys-in-love flicks is that the characters they portray look like they were made by Mattel. They are all young, toned, white, cute, middle-class men with a token fag-hag clinging on.

Director Rose Troche on the set of Bedrooms and Hallways (1999)

We wouldn’t be fascinated by a routine Hollywood love story simply because the leading characters were heterosexual; we’d want them to be something else besides – interesting, perhaps, or funny. But in the late 90s, many gay filmmakers seemed to follow the idea that gayness itself was enough to make a character interesting.

It isn’t.

Film companies send emails and press releases to the gay press, urging critics to ask their readers to ‘support’ such gay-themed films on their release. But why should anyone buy a ticket to ‘support’ a film? And what message would it send to ‘support’ a gay film like Trick or Billy’s Hollywood Screen Kiss? That gay people should have romantic comedies just as dim and dumb as the straight versions – although it’s impossible to remember many recent straight films this cringeworthy.

The problem with these ‘screwball comedies’ and ‘gay date movies’ is that they’re all too cute and sugary, annoyingly trashy, with trite stories. As gay director Gregg Araki memorably remarked a few years ago, ‘Just because a movie is gay doesn’t make it good. I’d rather go see fuckin’ Coneheads than see most of them!’

‘If y’see my life as I do, y’realise it’s been one big metaphor for that journey to the human state known as respect.’

Lady Chablis in Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil

Nevertheless, there were some interesting gay-related films made towards the end of the 90s. Thom Fitzgerald’s Beefcake (1998) was a real gem, a film that looked at the 1950s muscle men’s magazines that were supposedly popular as health and fitness magazines, but in reality were primarily purchased by the still-underground homosexual community. The combination of interviews with the stars of that lost era with re-enactments of the events leading to Mizer’s trial made for a heady mix of biography, fantasy and social history, as well as a voyeuristic look at the underlying homoeroticism that really sold Physique Pictorial.

Another wonderful re-telling of a past Tinseltown tale also hit the big screen in 1998. Gods and Monsters was certainly one of the high points of 90s gay cinema, picking up a string of top industry awards around the world – BAFTAs, Golden Globes and, at the 1999 Academy Awards, Bill Condon even picked up the Oscar for Best Screenplay Adaptation.

Sir Ian McKellen remarked: ‘Over the last two decades there has been a considerable revolution in the treatment of gays and lesbians in plays and films. For too many years we were portrayed as villainous or stupid. I am proud to have been associated with Gods and Monsters, which boldly treated homosexuality as a fact of life, worthy of the same serious approach as any other aspect of human nature.’

In the 90s alone, three major actors had been nominated for the Best Actor Oscar while playing gay roles – Stephen Rea for The Crying Game, Tom Hanks for Philadelphia and Sir Ian McKellen for Gods and Monsters.

This strong standing left many wondering: Who says gay men aren’t mainstream?

US, 85 mins

Director/Writer: Todd Haynes

Cast: Buck Smith, Edith Meeks, Larry Maxwell, Susan Norman, Scott Renderer, James Lyons, John R Lombardi, Millie White

Genre: Drama/ Horror

One of the most audacious and original American films in years, Todd Haynes’ Poison was inspired by the works of Jean Genet.

A powerful and disturbing study of deviance, cultural conditioning and disease, the film comprises three segments, all separate but interrelated stories, shot in three strikingly unique cinematic styles. The three stories illustrate the lives of a people living outside the fringes of ‘normal’ society. There is ‘Hero’, the pseudo-documentary about a seven-year-old boy called Richie who kills his own father and flies away; ‘Horror’, a sci-fi spoof about a brilliant research scientist (Larry Maxwell) who discovers the source of the human sex drive but precipitates a frightening reaction; and ‘Homo’, about a prisoner who falls in love with a fellow inmate and becomes drowned in obsession, fantasy and violence.

As each compelling story is told, their themes become inextricably linked, and the tension intensifies, culminating in an explosive climax of unsettled emotions. The unifying thread is sex, the poison to which the title refers. In each of the three sections, sex is virtually synonymous with perversion, abuse, domination and disease.

Poison took certain liberties with Genet’s work but it captured his spirit in a way that’s rarely been equalled. In fact, it’s difficult to imagine a more vivid, skin-crawling depiction of sexual loathing.

Haynes received funding from the National Endowment for the Arts for Poison, and on the American DVD commentary he states that the NEA funding was a great help because it allowed him the independence to carry out his vision without having to worry about satisfying commercial studio interests. Unfortunately, Poison was cited by right-wing campaigners (along with Robert Mapplethorpe) as a reason why NEA funding should be stopped. Under Bush, it was.

UK, 107 mins

Director/Writer:Neil Jordan

Cast: Stephen Rea, Miranda Richardson, Forest Whitaker, Jaye Davidson

Genre: Political Thriller

Neil Jordan’s The Crying Game (1992) was the British thriller that took America by storm. Starting off in art houses in major metropolitan areas, it quickly became a social phenomenon and broke all box-office records.

Though a superb blend of social statement and political thriller, interest in the film spread primarily because of a shocking ‘secret’ in the plot, causing it to move into the major mainline movie theatres. It was subsequently nominated for nine Academy Awards.

Jordan’s film is set in London and Northern Ireland, and begins with the capture of a black English soldier by a group of IRA terrorists. One of the terrorists, Fergus (Stephen Rea), befriends the soldier, finding out about his exotic girlfriend Dil (Jaye Davidson) in London in the process. As events develop, the terrorist flees Northern Ireland and goes to London where he begins a relationship with the soldier’s girlfriend. The film then explores their relationship as the terrorist is pursued by his former colleagues.

At the outset a simple story – and this movie could have simply been an interesting thriller – essential to its plot is a twist that catapults the film into the realm of social statement. The girlfriend, as it turns out, is not a girl at all, but a transvestite.

So it’s impossible to ignore the fact that this film, like Kiss of the Spider Woman (1985) and Jordan’s own Mona Lisa (1986), really tries to involve its audiences in understanding gay and lesbian sensibilities. Through a thrilling sexual mystery, The Crying Game exposes mainstream cinemagoers to an attractive fantasy of alternative sexuality. It’s also a story of love in the time of AIDS with no reference to that terrifying subject.

Where Jordan’s film distinguishes itself from many other gay-themed films, though, is in the fact its homosexuals are ‘real’ people with whose loneliness, hurts and fears anyone can sympathise. Dil misses his soldier/lover and yearns for Fergus’s love, yet earns the audience’s respect as a loyal, funny friend to Fergus when love turns out not to be an option.

Rather than preaching the ‘victimisation’ of homosexuals, or showing over-the-top glitzy gay lifestyles, The Crying Game is instead an admirable film with a politically correct message, the acceptance of gay love and openly gay identity. As if this wasn’t enough, the film also comes complete with an astounding soundtrack, featuring the hypnotic title track performed by Boy George, as well as Lyle Lovett’s version of Stand By Your Man and the classic Percy Sledge hit When a Man Loves a Woman. The screenplay is a triumph of clarity, particularly since the film’s plot is so complicated, and the acting is also superb – no surprise then that The Crying Game was nominated for the Oscar for Best Picture.

Jaye Davidson (Dil) with Stephen Rea (Fergus)

US, 100 mins

Director/Writer: Gus Van Sant

Cast: River Phoenix, Keanu Reeves, James Russo, William Richert, Rodney Harvey, Udo Kier

Genre: Road Movie

When rumours began circulating around Hollywood that pin-up boys River Phoenix and Keanu Reeves would play gay hustlers in Gus Van Sant’s next movie, hearts – male and female – began pounding. The rumours turned out to be true, unlike the tabloid reports that Reeves had married music mogul David Geffen at a secret ceremony in Hawaii.

My Own Private Idaho was soon hyped up as a ‘mainstream’ gay movie and really did deserve to become a cult classic of gay cinema. Made for two and a half million dollars, in 1991, it made around seven million dollars at the US box office. It also won several awards at film festivals around the world, mainly for Phoenix’s performance (he won Best Actor at Venice), and for Van Sant’s brilliant screenplay, tenuously based on Shakespeare’s Henry IV plays, which further develops the themes and concerns of his previous two features Mala Noche (1985) and Drugstore Cowboy (1989).

Phoenix plays the lonely, narcoleptic Mike. He has never known his father, and his mother abandoned him when he was young, so he’s not a very secure or well-adjusted individual. Living on the edge of destitution, he survives by working as a male prostitute, mainly servicing middle-aged men, although his clients range from a Capote-like compulsive who likes his bathtubs well scrubbed to a rich dame who likes her boys all at once.

River Phoenix in the arms of Keanu Reeves

Reeves is Scott, the brash eldest son of a wealthy family, who also works the streets in the Pacific Northwest. Despite their completely different backgrounds, they become friends. The pair spend time hanging with a ragged street family in a condemned building and, in a deliberate reworking of Orson Welles’s Shakespearean Chimes at Midnight, they converse in bard-speak. In fact, Van Sant’s cinematic references are extremely varied. Away from the Shakespearian stuff, the long empty roads and landscapes recall James William Guercio’s Electra Glide in Blue (1973), while Mike and Scott’s entire journey is akin to Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman’s trip in John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969).

Mike and Scott set out, in vain, on a search for Mike’s mother, a journey that takes them to Idaho, then to Italy. Mike passes out regularly and is usually carried to safety and protected by Scott. Along the way, Mike’s emotional attachment to Scott develops, but is rewarded only with friendship. In fact, Scott has no intentions of sticking with his friends once he receives his inheritance, due in a week. He plans to abandon his wanton lifestyle and become a respectable member of society at the very moment when his family least expects him to.

During his sleep Mike is visited by the vision of his mother who strokes his hair and tells him repeatedly, ‘Don’t worry; everything’s going to be alright.' A close shot of his sleeping face then changes to show his face approaching orgasm as he receives oral sex from a client in Seattle. His passion is shown by salmon leaping, his orgasm by a shot of a wooden barn dropping and shattering on a desert landscape.

On their travels to Italy, they discover that Mike’s mother has returned to the US long before but Scott begins a relationship with an Italian girl, deserts Mike and returns to Portland to claim his inheritance. A raw and sometimes shocking story of two guys’ struggle to come of age and to terms with reality, My Own Private Idaho is a poetic film about desire and the desperate need to belong. It has remained one of the best-known films in American gay cinema, mainly due to the subsequent career successes of Van Sant and Reeves, and the enduring pop mythology of River Phoenix, who died of a drug overdose in 1993.

The film’s final scene shows Mike alone on a road in Idaho in a narcoleptic state again; Scott is no longer there for him. Mike will never find what he’s looking for. For him, real love, intimacy and lust combined are distant dreams, more accessible in sleep, perhaps, than in waking. But the film was never more tender or moving than the moment Mike confronts his love for Scott. His murmured plea, ‘I really want to kiss you, man,' as they sit round a campfire, is nothing short of heartbreaking, a scene which helps make this a modern gay classic.

US, 92 mins

Director/Writer: Richard Glatzer

Cast: Craig Chester, Illeana Douglas, Alexis Arquette, Kent Fuher

Genre: Comedy

Dubbed ‘the out version of Soapdish’, Richard Glatzer’s first feature film, Grief, is a good example of 90s ‘AIDS Cinema’. Released in 1994 to international acclaim, it’s one of the sharpest gay indie films of the 90s.

Made on a micro-budget of just $40,000 and shot in ten days, Grief is a deeply heart-warming movie, full of humour (with jokes about semen stains, leprosy and circus lesbians!) but also full of compassion. Winner of awards at both the San Francisco Gay and Lesbian Festival and the Torino Festival, Grief deservedly became a cult hit and finally earned a DVD release in 2004.

The bittersweet comedy follows the frenzied and romantic antics of the outlandish staff of The Love Judge, a low-budget, daytime-TV show. Starring Last Exit to Brooklyn’s Alexis Arquette, Swoon’s Craig Chester, and Illeana Douglas from Alive, Grief centres on the show’s writer, Mark (Chester), who is mourning his lover’s death from AIDS and yet has a crush on a ‘straight’ co-worker Bill (Arquette), who sends back very mixed signals.

Director Richard Glatzer used to produce the TV show Divorce Court, so the film has a true sense of the absurdity of cheap television. Glatzer even throws in some amusing courtroom cameos, including Mary Woronov and Paul Bartel.

A decade after the film’s release, Glatzer remarked: ‘Funny how ten years on, the film already benefits from the patina of nostalgia. Big hair and bright fabrics were about to bite the dust. Courtroom shows would soon give way to reality TV. Protease inhibitors were just around the corner. I didn’t realise when we were making Grief that we were capturing a very specific point in time, but we were.’

Nevertheless, the chief reason for Grief was so that Glatzer could make a film that examined his feelings about surviving the loss of his lover. Said Glatzer: ‘That had been the lowest point of my life, and yet somehow I could only write about it comically. I’m not even sure if, at the time, I saw the film as a comedy. I think I felt I could coerce an audience into sharing my misery by enticing them with a few jokes. I do know that the only way I could address the film’s eponymous subject was indirectly. To see Mark at home crying himself to sleep was impossible for me. Much better to glimpse his emotional distress fleetingly, while he cranked out trash TV.’

On this level, Grief digs deeper than comparable mainstream projects. Chester’s character is extremely well rounded; not just another empty stereotype but more a great gay prototype. He’s cold, jaded and bitchy on the outside but tender and vulnerable on the inside – and this double-edged performance really helps in the film’s poignant finale.

US, 125 mins

Writer: Ron Nyswaner

Director: Jonathan Demme

Cast: Tom Hanks, Denzel Washington,

Antonio Banderas, Roberta Maxwell, Buzz Kilman, Karen Finley

Genre: AIDS drama

Jonathan Demme’s weepy pic had sanctimonious Tom Hanks as Andy Beckett, a respected member of a prestigious legal firm. But within months of being promoted, he’s out, a victim, he claims, of unfair dismissal. And this was one of the most controversial aspects of the film when it was initially released. While everybody knew it was about AIDS, the emphasis was on human rights and the rule of law – a David and Goliath struggle between a stricken individual and a powerful adversary. In fact, promotion for the film carefully avoided any reference to AIDS, using the slogan: ‘No one would take on his case, until one man was willing to take on the system.'

The man who steps in to defend Beckett is black lawyer Joe Miller. He knows all about discrimination but his own deep-seated prejudice against homosexuals becomes one of the principal conflicts in the drama.

The film, however, reinforced stereotypes and was far too timid in its depiction of same-sex relationships. The role of Hanks’ lover Miguel (Antonio Banderas) was drastically cut and any affection between the two characters is kept to a bare minimum, to the point where Banderas is only ever seen to kiss Hanks’ hands. The pair don’t even appear to have any gay friends. It seems the Hanks character has only ever made one mistake in his life. Other than that, he’s the perfect guy with the perfect boyfriend and the perfect, supportive family and perfect, caring friends. Where a seedier character might earn less sympathy, viewers won’t think Beckett ‘deserves’ his AIDS. Indeed, everything about the Hanks character is so wonderful and flawless that the movie lacks reality; it would certainly have been more interesting if its lead had some genuine flaws.

Nevertheless, there’s no denying its popularity at the box office and it was no great shock when the lead role brought Hanks the first of two successive Academy Awards.

US, 144 mins

Director: Roger Spottiswoode

Cast: Matthew Modine, Lily Tomlin, Richard Gere, Alan Alda, Sir Ian McKellen

Genre: AIDS drama

And the Band Played On, an HBO TV movie, debuted in September 1993, not long after the release of the big-budget Hollywood AIDS movie Philadelphia. It is an account of the first efforts by medical researchers to identify and define the epidemic.

Matthew Modine delivers an excellent performance as the film’s central character, a doctor who witnesses both the outbreak of the disease and its far-reaching social impact.

But the TV film is also remembered for its array of star cameo appearances including Richard Gere, Steve Martin and Phil Collins. Lily Tomlin is great as the cantankerous Dr Selma Dritz of the San Francisco Department of Public Health, on a righteous crusade, cruising the gay bathhouses, confronting the secret STD-doctors of the closeted elite, looking for solutions and providing the necessary outbursts. Sir Ian McKellen received an Emmy nomination for his performance as a San Francisco gay activist who campaigns for AIDS education at the cost of his lover.

Unlike Philadelphia, which simply shored up a bit of sympathy for a too-good-to-be-true victim, And the Band Played On decided to dole out the blame where blame was deserved. Ronald Reagan is the worthy villain, at the top of the bureaucracy heap, announcing an increase in defence spending as Modine scrapes away in his lab, looking for meagre funds for a new electron microscope.

And the Band Played On’s screenwriters were highly astute at turning social arguments into realistic and meaningful dialogue – always in character – and, unlike Philadelphia’s homo-ignorance and preachy tone, its passion and anger makes for a far more powerful and engrossing film.

Australia, 104 mins

Director/Writer: Stephan Elliott

Cast: Terence Stamp, Hugo Weaving, Guy Pearce,

Bill Hunter

Genre: Road movie – musical comedy

The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert is an extraordinary Australian road movie, extraordinary mainly for the amazing camp performances by the three, straight, leading actors.

Priscilla is about two drag queens (Anthony/Mitzi and Adam/Felicia) and a transsexual (Bernadette) who are hired to perform a drag show at a resort in Alice Springs in the remote Australian desert. The flamboyant trio are Hugo Weaving and Guy Pearce (as the two queens) and Terence Stamp (as the world-weary transsexual). They take a tour bus (called Priscilla) west from Sydney, across the enormous Outback – a journey full of bitchy banter and outrageous incidents. En route, it is discovered that the woman they’ve contracted with is Anthony’s wife. Their bus breaks down, and is repaired by gruff mechanic Bob (Bill Hunter), a big fan from the past, who travels on with them. It’s not long before our three favourite queens are performing their own inimitable version of ‘I Will Survive’.

For all the tack and bitchiness, there are some really understated moments and emotional scenes, and lots of gay issues are explored. In one key development, Stamp is plunged into despair by the death of someone close to him and this is where the 60s British icon shines. He is totally credible and utterly dignified.

The three main characters – one gay guy, one bisexual and a transsexual – represent three highly segregated communities. And they all detest each other. Only the danger and hardship of the journey unite them. Viewers need to watch closely to pick up on the subtleties in this movie. In fact, viewing several times would help. In the end, Adam gets to fulfil his dream of climbing to the top of King’s Canyon in a Gaultier frock, tiara and heels; Mitzi faces up to being a father; and Bernadette gets her man.

We are told Bernadette is an ex Les Girl. In fact, the inspiration for the film was Play Girls, the touring troupe of the acclaimed cabaret group Les Girls. This group achieved iconic status in Australia and featured Carlotta, the Balmain Boy who had Australia’s first recognised sex-change operation. Australia was also one of the most loyal audiences for Abba, and Lasse Hallström’s Abba: The Movie (1977) was filmed on their Australian tour. So in Australia at least, a cultural precedent had already been put in place for the mainstream acceptance of Priscilla on its release and thus provided the springboard for its international distribution and success.

Priscilla is a ready-made gay cult movie, complete with all of the vital ingredients, including countless memorable lines of dialogue, which include stabs at Abba – ‘I’ve said it once and I’ll say it again – no more fucking Abba’; ‘What are you telling me – this is an Abba turd?’ The camp 70s soundtrack is to die for – Abba, Village People, CeCe Peniston, Gloria Gaynor, M People; both originals and exclusive dance remixes. The movie even inspired some theatres to get into the spirit of things by hanging disco balls from the ceiling and flashing coloured lights when the ‘Finally’ dance played out on screen. In addition to the wonderful soundtrack, the gaudy costumes were fabulous and won a well-deserved Oscar.

Later, Hugo Weaving was also happy to play a gay man in Rose Troche’s Bedrooms and Hallways (1999) and Guy Pearce, having shaken off his soap-star past, broke into Hollywood, with some very meaty roles in films like Memento and LA Confidential.

Interestingly, around the same time Priscilla, Queen of the Desert was released, the same country also brought us Muriel’s Wedding (1994), a tale about a social misfit who copes with the screwed-up reality of small-town society by listening to Abba’s ‘Dancing Queen’. Sound familiar?

US, 104 mins

Writer: Douglas Carter Beane

Director: Beeban Kidron

Cast: Wesley Snipes, Patrick Swayze, John Leguizamo, Stockard Channing, Blythe Danner, Arliss Howard, Chris Penn

The success of the hit Aussie, drag-queen movie Priscilla resulted in a cash-in movie from Hollywood, To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar (1995).

Producing a similar off-beat road movie about drag queens, this time it was Patrick Swayze, Wesley Snipes and John Leguizamo who were glamming it up. En route from New York to Hollywood for a drag-queen beauty pageant, the trio is forced to take an unwelcome detour. Stranded in the tiny Midwest town of Snydersville, the three make the best of the unfortunate situation as their glitz and glamour shake up the sleepy locals.

It’s all flamboyant fun but, like most real-life drag queens, much of To Wong Foo’s material is old and tired and this Hollywood effort failed to tap into the same nerve that Priscilla did with its innovative subject matter and sensitive character portrayals. Priscilla’s campy trio were far more impressive in a film in which the glitz and glamour seemed far more stylish – less Hollywood and more appealing and believable to a gay audience. It’s fair to say that To Wong Foo provides a point of comparison which can only reinforce Priscilla’s reputation.

Wesley Snipes (left), John Leguizamo (centre) and Patrick Swayze (right) glamming it up

UK, 85 mins

Director: Hettie MacDonald

Writer: Jonathan Harvey

Cast: Meera Syal, Linda Henry, Martin Walsh, Glen Berry, Scott Neal, Steven M Martin, Andrew Fraser, Tameka Empson

Genre: Coming-of-age

Set during a long hot summer on a housing estate in South London, and released in 1996, Beautiful Thing turned out to be one of the most tender love stories ever told on film. A story of sexual awakening, this urban fairytale depicts what it’s like to be sixteen and in the throes of bashful first love. Hettie MacDonald’s delightful debut feature charts a seemingly unlikely romance between two teenagers, from first nervous glances to ingenious use of Peppermint Foot Lotion!

Jamie, an unpopular kid who skips school to avoid games lessons, lives next door to Ste, a more popular athletic boy but who is constantly beaten up by his father and older brother. Jamie’s mum, Sandra, offers refuge to Ste, who has to ‘top-and-tail’ with Jamie.

There are obvious issues covered, such as the boys’ coming to terms with their sexuality and others finding out. But the film also details Sandra’s unconditional love, loyalty and defence of Jamie and the fear of repercussion should Ste’s family find out. The character of Sandra is extremely well rounded and we get a real sense of her dreams of promotion and desire to manage her own pub, and escape the estate, and of her new relationship with her hippie boyfriend Tony. Girl next door, Leah, is another great character. Having been expelled from school, she spends her time listening to Mama Cass records and tripping on a variety of drugs.

Understandably, the film struck a chord with the gay community and there’s undoubtedly a cult of Beautiful Thing. Those teenagers in particular who sent themselves deep into denial about their sexuality have taken the film to their hearts.

Looking at the numerous fan websites, Beautiful Thing chat-rooms and email discussion pages, it seems the movie has affected people most powerfully if they’ve had a hard time accepting themselves. One fan explained how the strongest reaction he heard came from a man he knew in his late 40s who came out recently to his wife and grown sons, straight after seeing the film. One other fan described how he’d been to London before but now planned to go to Thamesmead in the summer. ‘Can you imagine,’ he wrote, ‘there’ll be all these poofs walking around with maps looking for Beautiful Thing locations!’ The same writer explained how he and his new boyfriend Andi – also a huge fan of the film – planned on putting together a tour plan, and maybe using it as an excuse for BT fans to meet sometime the following summer. Other sites include virtual tours of Thamesmead, with maps and photos.

Most film critics missed the groundbreaking nature of the film – and criticised the (deliberate) happy ending – saying it was unrealistic (unlike, apparently, The Birdcage). The film has, however, been taken up by many high-school teachers (mainly in the US) who play it to their classes to convey the message to both gays and straights that ‘it’s okay now’.

UK, 100 mins

Director: Sean Mathias

Writer: Martin Sherman

Cast: Clive Owen, Lothaire Bluteau, Brian Webber, Sir Ian McKellen, Mick Jagger

When Sean Mathias’s Bent was released in 1996, most critics agreed it was just as powerful and moving as the award-winning stage play upon which it was based. Both Fassbinder and Costa-Gavras wanted to film Martin Sherman’s 1979 play about gay persecution under the Nazis, but it was theatre director Mathias who finally brought it to the screen.

Set amidst the decadence of pre-war, fascist Germany, it tells the story of three homosexual men’s fight for survival in the face of persecution. The film opens with promiscuous partier Max (Clive Owen) and his flatmate Rudi (Brian Webber) enjoying a coke-fuelled evening’s entertainment at a decadent club. Flamboyant dancers and circus performers revel with customers in various sorts of public ‘debauchery’, while a transvestite nightclub singer named Greta/George (Mick Jagger) warbles a tune about all the beautiful boys and the intoxicating nightlife.

But Nazi thugs are also out in Berlin that evening, the infamous Night of the Long Knives, and Max, who’s picked up a man for the night, has been followed back to his apartment. Stormtroopers burst in and kill his one night stand, as Max makes his escape.

Despite pleas from his uncle (Sir Ian McKellen), Max refuses to flee Germany unless he can get Rudi out with him.

Clive Owen as Max in scenes from Bent

The pair set off into the woods, only to be caught and shipped in a boxcar full of prisoners to the concentration camp at Dachau. Their time in the woods, which alternates between sheer terror and the gentle prayer of their love for each other, is handled well by director Mathias, as are the blindingly horrific events of the train ride. At one point, Max is forced to beat his lover to death then prove his manhood by having intercourse with a young girl who’s been shot in the head.

En route, Max is befriended by a timid gay man named Horst (Lothaire Bluteau), who advises him not to acknowledge his lover if he wishes to remain alive. Following that advice allows Max to survive after Rudi is beaten to death. Later, by ‘performing’ with a young girl to convince the Nazis of his heterosexuality, Max is able to ‘upgrade’ his status from that of a homosexual (who must wear a pink triangle) to that of a Jew (who wears a yellow star).

Within the confines of the camp, however, Max and Horst develop a secret love affair and through the most terrible torture they overcome the oppression. In one moving scene the two men take the opportunity to ‘make love’ to each other by describing various sex acts sotto voce while the guards look down on them as they pointlessly move rocks from one side of a quarry to the other. They’re not allowed to touch or even look at one another but still manage to share this explicit imaginary sexual encounter. ‘We feel we’re human,’ says Horst afterwards. ‘They’re not going to kill us.’

Max and Horst’s secret love affair is as inspirational as it is emotional, and Mathias’s film illustrates how the selfless love of one person for another can overcome oppression, even under the most extreme circumstances.

Czech Republic, 134 mins

Director: Wiktor Grodecki

Cast: Miroslav Caslavka, David Svec, Miroslav Breu, Jiri Kodes, Karel Polisenksy, Pavel Skripal, Richard Toth

Genre: Sex industry drama

Sixteen-year-old Marek (Miroslav Caslavka), a boy with an angelic face and a freshly stolen jacket, is about to embark on an adventure. He’s run away from his life back home with an overpowering father and arrived at the main train station in the busy city of Prague.

He’s immediately spotted by a man called Honza, who asks him if he wants to earn some quick cash. The boy is too naive to realise he’s being set up as a prostitute. He is drugged and wakes in the room of a gay client who has just had sex with him. Shaken, he takes his payment from the man and returns to the train station where Honza demands his cut.

Marek meets David (David Svec who also co-wrote the film and won the Prize of the City of Setúbal for his performance), another street hustler. After befriending each other, they decide to become pimps themselves by combining their money together to purchase a handful of young men. When that fails, they turn to petty crimes. With each step forward Marek and David take, they find themselves at least three steps back. In the end, Marek is addicted to drugs, sick from AIDS, and maggots and worms eat away at his skin while he sits at the base of a public toilet. He slashes his leg with a knife, unaware that his father who has come in search of him is just a mere two feet away in another stall.

In less than a year (and within 135 minutes – the running time of this film) Marek has become a street prostitute, a drug addict, a porn star, and worse of all – a statistic. He ends up just one of the hundreds of young men who flock to Prague each year in search of freedom – only to end up trapped.

Director Wiktor Grodecki, who had previously made Not Angels But Angels and Body Without Soul – two documentaries which influenced Mandragora – used real-life prostitutes and a non-professional cast to depict the despair and tragedy that infects so many young adults in Prague.

He ends this dramatisation by showing yet another young man getting off a train in Prague. He, like Marek and countless others before him, steps off the platform and proceeds to walk down the stairs and through the tunnel that will perhaps lead him to Honza or someone like him.

In case you’re wondering about the film’s title, Mandragora (also known as Mandrake) is a plant from North Africa, a plant that has been described as ‘having magic power to heal a great variety of diseases, to induce a feeling of love, affection and happiness’. According to East Indian folklore, it was also thought that Mandragora grew under the gallows from the sperm of hanged men.

Although the acting is good and the lighting and sets are all well done, ultimately, Mandragora is marred by Grodecki’s heavy hand. The pathos is laid on rather too thick and, at 134 minutes, the film is far too long to sustain such a one-dimensional approach.

UK, 110 mins

Director: Simon Shore

Writer: Patrick Wilde

Cast: Ben Silverstone, Brad Gorton, Charlotte

Brittain, Stacy Hart

Genre: Coming-of-age

Following the success of Beautiful Thing (1995), British gay cinema produced another excellent film, accessible to all audiences, in the shape of Get Real (1998), which tells the story of a teenage boy who has become sexually active at 16. As Roger Ebert memorably remarked in his review at the time: ‘When straight teenagers do it, it’s called sowing wild oats. When gay teenagers do it, it’s hedonistic promiscuity.’ The film obviously offended many but the point is that most teenagers have sex. Some are gay. Fact.

Ben Silverstone plays Steven Carter, a 16-year-old who lives in leafy, stuffy Basingstoke. Although comfortable with his sexuality, he knows neither his parents nor schoolmates are ready for the news. Until, that is, he forms an unlikely relationship with John Dixon (Brad Gorton), star athlete and all-round school hunk. Wary of damaging his cool image, John insists the romance remains secret, although Steven finds this easier said than done.

Charlotte Brittain plays Steven’s next-door-neighbour Linda, the only person who knows he is gay. Much of the humour in the film comes from the scenes between these two characters. Steven’s cover as well as confidante, she even faints at a wedding when he needs to make a quick getaway.

There is also Jessica (Stacy A Hart), an editor on the school magazine, who likes Steven a lot and wants to be his girlfriend. He wants to tell her the truth, but lacks the courage. Then the relationship with John helps him to see his life more clearly, to grow tired of lying, and he writes an anonymous article for the magazine that is not destined to remain anonymous for long.

Like Beautiful Thing, Simon Shore’s feature argues that we are as we are, and the best thing to do is accept that. The gay themes are handled with an admirable lack of fuss and this is far better made than most of Hollywood’s recent straight teen love weepies.

UK, 95 mins

Director: Paul Oremland

Writer: Robert Gray

Cast: Roger Daltrey, Dani Behr, Ian Rose, Steve Bell

Genre: Romantic drama

Aimed at the audience that made a success of Beautiful Thing, another British movie about gay youth, Like It Is was released in 1998, adding a class-conflict dimension by pairing a London record producer with a working-class boxer.

In this sexy drama, set around London’s gay club world, we follow the two young men as they fall in love, despite enormously different backgrounds. Steve Bell gives an unforgettable performance as Craig, the Blackpool fighter who is struggling with his sexual identity; Ian Rose plays the ultra-cool urbanite Matt who knows everybody; and Roger Daltrey (of The Who) is wickedly funny as Ian’s bitchy gay boss Kelvin.

Daltrey steals the whole movie. He’s like one of those flesh-eating villainesses in a Disney animation feature – overwrought, campy and full of malice. A deliciously unscrupulous record company and club impresario, this vicious old queen’s regular collagen injections and steady diet of fresh young boys keep him trim and ever ready. For laughs, it seems, he tries to draw a wedge between the two young lovers. Also trying to keep them apart is Matt’s roommate Paula (Dani Behr), a singer who resents Craig’s intrusion.

Roger Daltrey, Ian Rose and Steve Bell

What’s most interesting about Like It Is is the nature of the relationship between Matt and Craig. Unusually for gay screen romances, their courtship is slight. Matt, who is described as a ‘serial shagger’, works for Kelvin and meets Craig on an out-of-town trip, but their attempt at sex reveals that Craig has some issues to work out regarding his homosexuality. Craig earns money boxing in illegal bare-knuckles fights, but soon moves down to London to seek out Matt; but the fast-paced world of the druggy club scene is a bit out of Craig’s league.

Like It Is offers an enjoyable and positive look at gay life and has a welcome, realistic feel. It’s romantic, honest, and, above all, entertaining.

US, 106 mins

Writer/Director: Bill Condon

Cast: Sir Ian McKellen, Brendan Fraser, Lynn Redgrave, Lolita Davidovich

One of the most critically acclaimed gay-interest films of the late 1990s, Gods and Monsters was the winner of several awards including the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Bill Condon’s film is a tribute to the controversial life of the eccentric genius, James Whale, who died in 1957. The director of Frankenstein and 20 other films of the 1930s and 40s was openly gay at a time when homosexuality in Hollywood was discreetly concealed.

The film stars Sir Ian McKellen in a sublime performance as the white-haired Whale, who is portrayed as a dapper gent and amateur artist prompted by failing health into melancholy remembrance of things past. Flashbacks of lost love, World War I battle trauma, and glory days in Hollywood combine with Whale’s present-day attraction to a newly hired yard worker (Brendan Fraser) whose hunky, Frankenstein-like physique makes him an ideal model for Whale’s fixated sketching.

The friendship between the handsome gardener and his elderly gay admirer is by turns tenuous, humorous, mutually beneficial and, ultimately, rather sad – but to Condon’s credit Whale is never seen as pathetic, lecherous or senile. Equally rich is the rapport between Whale and his long-time housekeeper (played with wry sarcasm by Lynn Redgrave), who serves as protector, mother, and even surrogate spouse while Whale’s mental state deteriorates. Flashbacks to Whale’s filmmaking days are painstakingly authentic (particularly in the casting of lookalike actors playing Boris Karloff and Elsa Lanchester), and all of these ingredients combine to make Gods and Monsters (executive produced by horror novelist-filmmaker Clive Barker) a touchingly affectionate film that succeeds on many levels.

Sir Ian McKellen (as James Whale) with Brendan Fraser (as Clayton Boone)

Openly gay, experimental filmmaker Todd Haynes burst upon the scene two years after his graduation from Brown University with his now-infamous 43-minute cult treasure Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1988). Seizing upon the inspired gimmick of using Barbie and Ken dolls to sympathetically recount the story of the pop star’s death from anorexia, he spent months making miniature dishes, chairs, costumes, Kleenex and Ex-Lax boxes, and Carpenters’ records to create the film’s intricate, doll-size mise-en-scène. The result was both audacious and accomplished as the dolls seemingly ceased to be dolls, leaving the audience weeping for the tragic singer. Unfortunately, Richard Carpenter’s enmity for the film (which made him look like a selfish jerk) led to the serving of a ‘cease and desist’ order in 1989 and the film has never surfaced since.

Haynes’ award-winning first feature, Poison (1991), was inspired by the prison writings of Jean Genet, and recalls Werner Fassbinder’s unrestrainedly gay Querelle. Steeped in obsession, violence and rape, it was not for the faint of heart, prompting walkouts at its 1991 Sundance Film Festival screening and cries of outrage from right-wing critics.

Haynes' next film, Safe (1995), was a very different project, the story of a woman suffering from a breakdown caused by a mysterious virus. She ends up in a strange clinic called Wrenwood, a new-age retreat for those who are ‘environmentally ill’, and even leaves her husband and stepson to try and find salvation there. Many thought the whole film was a metaphor for the AIDS virus. Considered to be an outstanding work, it was voted by many critics as their best film of the year.

Haynes took a highly personal look at the British glam-rock scene of the early 70s with Velvet Goldmine (1998), his biggest and most accessible film yet. Dazzlingly surreal with a vibrant glam-era soundtrack, it puts ordinary period filmmaking and time-capsule musicology to shame.

In Far From Heaven (2002), Haynes revisited, with little nostalgia, the almost forgotten genre of the domestic melodrama. Drawing from the ‘women’s films’ of the 1950s, he cast Julianne Moore as a 1957 Connecticut housewife and mother who finds out one day that her idyllic suburban life is a lie once she realises that her husband is having a homosexual affair. Haynes explodes the mythical shell of innocence enveloping films from the 50s and warns us that many of the period’s most confining concepts of sexuality and the rigid pursuit of complacency and stability are as alive and volatile today as they were in yesteryear’s precautionary tales from suburbia.

Haynes’s film I’m Not There (2007) explores the world of Bob Dylan, where six characters embody a different aspect of the musician’s life and work. ‘The film is inspired by Dylan’s music and his ability to recreate and reimagine himself time and time again,’ according to key producer, Christine Vachon. Featuring Heath Ledger, Richard Gere, Christian Bale and Cate Blanchett, it was the first biographical feature project to secure the approval of the pop-culture icon.

Later, in 2011, Haynes directed Mildred Pierce, a five-hour miniseries for HBO starring Kate Winslet in the title role originally played by Joan Crawford in 1945.

Long considered one of the finest British stage actors, Sir Ian McKellen has defied the conventional wisdom that being openly homosexual would either pigeonhole you or destroy your career. Since his 1988 decision to come out during a BBC radio broadcast, he has not only been knighted for his services to the theatre (in 1991) but found himself an unlikely movie star.

Joining the National Theatre in 1965, much of McKellen’s work was on the stage, where he played a variety of roles from the Shakespeare canon. But he became an international star for two contemporary parts. In 1979, he created the role of Max, a gay man who pretends to be Jewish when he is shipped to a concentration camp, in Martin Sherman’s groundbreaking Bent. The following year, McKellen took the role of Salieri, the jealous rival of Mozart, in Peter Shaffer’s fine Amadeus. Recreating the latter on Broadway only increased his stature, which was capped when he won a Tony Award for the role.

Although he has continued to appear on stage throughout the world, post-Amadeus McKellen found himself in demand for film and television roles.

Spurred by legislation that prohibited local authorities from promoting ‘homosexual causes’, McKellen disclosed his gayness on a 1988 BBC radio broadcast. While it made headlines in the United Kingdom and spawned much conjecture that he would be typecast in future parts, the actor confounded his critics by undertaking the role of John Profumo, a politician brought down by a notorious heterosexual sex scandal in the 60s in Scandal (1989). Fully embodying a manly character, the actor demonstrated that his own sexual orientation was immaterial to his abilities as a performer.

Beginning to become more active in gay-related causes, he recreated the role of Max in a one-night-only staging of Bent that led to a 1990 revival, accepted the role of AIDS activist Bill Kraus in the HBO movie And the Band Played On (1993) and devised his one-man show A Knight Out, which he often performs as a benefit fundraiser.

Following a well-received supporting performance as Russian Czar Nicholas II in the HBO drama Rasputin (1996), McKellen accepted the smaller role of Freddie, who attempts to help Max escape from the Nazis, in the feature version of Bent (1997). The next year, as he approached his 60s, McKellen’s undeniable triumph was playing James Whale, the expatriate British film director best known for his Frankenstein horror films, in Bill Condon’s superlative Gods and Monsters. McKellen found numerous parallels between their lives. Both hailed from the same area of England, both started their careers on stage as actors and both were homosexual, which informed his deeply moving characterisation and helped him nab an Oscar nomination.

More recently, McKellen has played Patrick Stewart’s evil rival Magneto in X-Men (2000), and in the same year signed on to play the wizard Gandalf in Peter Jackson’s eagerly anticipated Lord of the Rings trilogy. Giving another stellar performance, alternately charming and commanding, he earned rave reviews and numerous award nominations for his portrayal, as well as the hearts of fans for his dedication to the role. Making another subset of fans equally happy, McKellen reprised the role of the villainous Magneto for a string of X Men comic-book sequels throughout the next decade.

McKellen is, arguably, the most famous gay actor in the world, recently named the most influential gay man in Britain, having topped the Pink List. But he’s more than just a household name. One of the founders of Stonewall in the UK, a charitable organisation which tries to influence legal and social change in regard to gays and lesbians, McKellen has sought to use the power of his celebrity to fight homophobia and anti-gay discrimination around the world. He spoke out in 1988 against the United Kingdom’s homophobic legislation known as Section 28, and he continues to speak out today against intolerance everywhere. ‘Twenty years ago,' he says, ‘the only stories you ever read in the newspapers were entirely negative. Gay people were only treated as news items if some sensation had occurred. That really has changed, at least in the UK, and it would be a very brave newspaper these days that only treated gays and lesbians as a matter of sensation.’

As for Hollywood, McKellen maintains it’s still very difficult for a gay actor to be open about their sexuality. Speaking to afterelton.com in 2006 he said, ‘My agent in London counselled me against coming out when I did and I’m sure that still happens in Hollywood. Yes, I’m sure the advice to young actors is, “Don’t come out, [or] you’ll never be a young film star playing romantic roles.”’

McKellen continued: ‘I was disappointed… when Tom Cruise took someone to court on the grounds that to even suggest or lie that he, Tom Cruise, had had gay sex experiences was detrimental to his career because he would no longer be convincing playing the sort of parts that he plays on film. That is such palpable nonsense. It shows a very innocent, ignorant view of what acting is and what an audience knows about actors.

‘There is no confusion in the audience’s mind when they see an actor playing a part. You might as well say that the point at which Tom Cruise got divorced and became a single man he could never in the future be convincing as a married man on film. It doesn’t make sense. Or that an actor who wears a wig is not convincing because we all know he is bald. It really doesn’t work like that. He should’ve been called on that. I’m not interested in whether Tom Cruise is gay or not. Whether he’s lying or not is a matter none of us can judge. But that he should say that if he were thought to be gay, he could no longer ever be taken seriously playing heterosexual parts, it doesn’t work like that. Otherwise, I wouldn’t keep playing all these heterosexual parts I keep getting offered.’

Gus Van Sant’s poetic yet clear-eyed excursions through America’s seamy, skid-row underbelly have yielded some of the more potent independent films of the late 1980s and early 90s. ‘I guess I’m interested in sociopathic people,’ he has stated, ‘in life and in my movies.’ With art-school training in painting as well as film, Van Sant worked in commercials before entering the film industry by making small personal films that played the festival circuit, notably in highbrow gay and lesbian venues. Openly gay, he has dealt unflinchingly with homosexual and other marginalised subcultures without being particularly concerned about providing positive role models.

Van Sant’s first feature, Mala Noche (1985), is a dreamy black-and-white rumination on the doomed relationship between a teen Mexican migrant worker and a liquor-store clerk. Made for about $25,000, it won a Los Angeles Film Critics Award as the best independent/experimental film of 1987.

Drugstore Cowboy (1989) chronicles the exploits of a rootless druggie (Matt Dillon) and his ‘crew’ who survive by robbing West Coast pharmacies. Lyrically shot, and boasting superb performances from Dillon and co-star Kelly Lynch, the film marked Van Sant as a director of considerable promise.

Van Sant’s 1991 feature, My Own Private Idaho, based on his first original screenplay, starred River Phoenix as a narcoleptic male prostitute whose search for home and family takes him from Portland, Oregon, to such disparate locales as Idaho and Italy. Keanu Reeves plays his well-heeled companion of the streets and son of the local mayor.

After Idaho, the trades buzzed that Van Sant would make his Hollywood studio debut as the director of The Mayor of Castro Street, based on Randy Shilts’ book about San Francisco’s assassinated, openly gay city supervisor Harvey Milk. Oliver Stone was set to produce and Robin Williams reportedly wanted the lead. The project eventually fell apart due to the creative differences between Van Sant and Stone over the screenplay.

Van Sant returned to familiar territory – another indie road picture centring on an outsider (budgeted at $7.5 million), Even Cowgirls Get the Blues (1994), adapted from Tom Robbins’ 1976 cult novel about a young woman whose outsized thumbs make her a formidable hitchhiker.

Next came Van Sant’s To Die For (1995), his first major studio project. The film was inspired by the true story of a high-school teacher who seduced her teenage lover into murdering her husband. A modest commercial success, it was a critical hit for everyone involved, particularly its star Nicole Kidman who portrayed the media-obsessed careerist who romances Joaquin Phoenix into murdering Matt Dillon.

That same year, Van Sant served as executive producer on one of the more controversial films of 1995 – Larry Clark’s Kids, a ‘vérité’-styled drama about the sex and drug habits of a group of middle-class Manhattan teens. Some found the work profound, while others found it profoundly troubling for its ‘exploitive’ use of young actors.

As a follow-up, Van Sant returned to the director’s chair to make Good Will Hunting (1997), about an underachiever (Matt Damon) on the road to self-destruction who finds unlikely aid from several people, including a therapist (Robin Williams) and his best friend (Ben Affleck). Written by Damon and Affleck, it’s well crafted, if somewhat predictable.

The feature’s success, however, moved Van Sant further towards mainstream Hollywood, and with new-found clout he opted to direct a shot-by-shot 1998 remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 classic Psycho, a curious career move which left film purists fuming and audiences unmoved.

Van Sant achieved some slight redemption with his next effort, Finding Forrester (2000), a conventional but mostly effective tale (despite a white patriarchal undercurrent) in which a reclusive author (Sean Connery) mentors an inner-city poetry prodigy (Rob Brown).

Returning left of centre, Van Sant re-teamed with Matt Damon and Ben Affleck’s brother Casey, who co-wrote and starred in Gerry (2002), a highly unusual film in which two young men named Gerry are stranded and hopelessly lost during a hiking expedition. It put Van Sant squarely back on the road to more personalised and experimental filmmaking.

The arresting and remarkable Elephant (2003) is an abstract exploration of the contrast between banality and violence in American life, and stubbornly refuses to embrace any sort of conventional narrative. Named for the aphorism about the problematic pachyderm in the living room that’s so big that it goes ignored, the star-less Elephant follows students at a Portland high school until violence erupts, delivering Van Sant’s take on the murders that took place at Columbine High School. It earned Van Sant the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, as well as a Best Director award and the Cinema Prize of the French National Education System.

More recently, Van Sant made Last Days (2005), a Seattle-set, rock ‘n’ roll drama about a musician whose life and career is reminiscent of Kurt Cobain’s, and then Paranoid Park (2007) based on a novel by Blake Nelson and set in and around an infamous Portland skate park where a teenage boarder accidentally kills a security guard. The elliptical narrative of Paranoid Park was enhanced by an amazing sound mix, excellent skate scenes and impressive cinematography by Christopher Doyle. The young cast was recruited on MySpace and the film deservedly won the special 60th Anniversary Prize at Cannes.

A year later, Van Sant directed Milk (2008) about Harvey Milk, the San Francisco supervisor and first openly gay, elected official in the US, who was assassinated in 1977. Bryan Singer had been developing his own Harvey Milk project, working with his Usual Suspects writing partner, Christopher McQuarrie, but in the end, Van Sant got there first, signing Sean Penn for the title role. The film opened to strong reviews, and garnered a number of year-end awards, including eight Oscar nominations. In addition to Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay and Best Actor nods, the Academy bestowed the second Best Director nomination of his career on Van Sant.

In 2011, Van Sant returned to the director’s chair for the unusual fantasy Restless, with Mia Wasikowska and Henry Hopper as a couple whose paths intersect with the ghost of a World War II kamikaze pilot.