Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal in Brokeback Mountain

Although the 1990s ended on a high note with films such as Gods and Monsters (1998) and Beefcake (1998), these quality pictures were released amongst all of the dubious sitcom-style gay comedies. Unfortunately, early into the new millennium, it seemed that many gay filmmakers were still partying like it was 1999, so along came a load more of the ‘heartwarming’ gay-life-is-a-blast pics.

The decade began with The Broken Hearts Club (2000), another sunny light comedy about a group of guys who were all friends and just happened to be gay. Marketed as a ‘gay Big Chill’ or a ‘gay Diner’ it was clear from the outset that originality would not be its selling point. It was, however, talked up at Sundance because of the way the film apparently played down gay ‘issues’. And there were lots more equal opportunity offenders early on in the decade.

‘People get fucked up working at K-Mart. People get fucked up working in Hollywood. It’s called the adult film industry. If you’re going to work in it, you’d better be an adult.’

Silver in The Fluffer

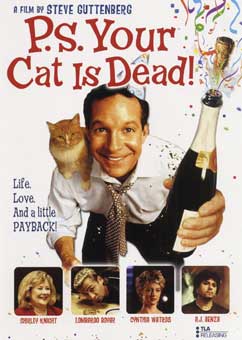

All Over the Guy (2001) was one dreadful entry in the glut of gay romantic comedies. Under One Roof (2002) was another, but with a more erotic slant that revolved around a Chinese-American mama’s boy who wants ‘to dip his chopstick in the rice bowl’ of a lanky Indiana slacker boy. Police Academy star Steve Guttenberg appeared in the long-awaited but disappointing film adaptation of gay writer James Kirkwood’s dark comedy P.S. Your Cat Is Dead! (2002), while ageing British actor Roger Moore popped up in another American gay-themed ‘comedy’, Boat Trip (2002), playing a flamboyant gay man who propositions Cuba Gooding Jr and Horatio Sanz, two straight men looking for romance who are mistakenly booked on a gay cruise. Talking about the movie, Moore recently admitted: ‘I sort of went back into the closet to do it. Half the actors I’ve worked with have been gay while pretending that they weren’t – so I imagined I was them.’

Nevertheless, we all know subtle and sensitive films about sexual politics are not usually made in Hollywood and Boat Trip was the usual garish, often offensive adult comedy. The negativity is pretty constant with gay men portrayed in the usual stereotypical way – so, we see a variety of cross-dressers, old queens, men in dog collars, Gooding Jr mincing about, screeching noisily, and donning drag for the cabaret, all this only feeding into the film’s underlying homophobia.

Friends and Family (2001) was another one-joke comedy, although not as negative as Boat Trip, this one about a gay couple who are also working as hit men for the Mafia. Then came the soap opera schlock of 200 American (2003), about an advertising executive who falls for a hustler, and Danny in the Sky (2001), yet another eye-candy comedy that boasts a story about a pretty boy who wants to be a model and escape from his gay dad, only to end up a stripper at a gay club. A year later came Eating Out (2004), a ‘screwball comedy’ about a hunky straight guy pretending he’s gay to get a date with a woman who only likes to hang out with gay men. The twisted reunion rom-com Adam & Steve (2005) followed and then came Another Gay Movie (2006), a spoof about four high school graduates’ mission to lose their anal virginity any way they can. It was a kind of gay American Pie or Porky’s, with all the toilet humour and crass behaviour to boot. Very un-PC with pure unadulterated in-your-face gay jokes from start to finish, but popular due to its raunchy scenes and gorgeous cast.

2007 also saw the release of Adam Sandler’s comedy film I Now Pronounce You Chuck & Larry, the latest and most successful title in this long line of gay-themed ‘wacky’ mainstream comedies. This one was concerned with two semi-homophobic firefighters pretending to be a gay couple to receive partnership benefits. A kind of reversed version of The Birdcage (where a gay couple pretend to be straight), this time it was a fake-gay-marriage story with two straight mates. A massive international hit, in the US the film knocked Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix from the number-one slot at the box office. But Sandler’s movie is a difficult one to assess. It was a film that brought the issue of gay marriage into the minds of millions of heterosexuals, and it claimed to support the idea of gay marriage, but yet again it was another example of a Hollywood movie being packed full of stereotypes that negate its message. Along with a barrage of the usual Adam Sandler Wedding Crasher-type fat jokes and crass comedy, Chuck and Larry delivers 90 minutes of gay caricatures, lapped up by audiences around the globe in a supposedly enlightened twenty-first century.

But Sandler’s co-star Kevin James defended the film, telling WENN: ‘We screened it for gay rights group GLAAD (the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation) because we certainly didn’t want to offend anybody in any way. The main reason of this movie is really just to make people laugh and that’s all we wanted to do. These guys are idiots in a way. They learn tolerance, what it’s about, and what happens when they have to pretend to be this way. That’s basically it, but we’re certainly not trying to tell people how to live their lives in any way, shape, or form.’

In reality, people should expect crass and offensive comedy from Sandler. Quite simply, it’s what he does. This is a movie that just wouldn’t work without the egregious gay stereotypes. I Now Pronounce You Chuck & Larry tries to turn itself around into a full defence of gay rights and a celebration of gay culture by the end, even boasting appearances by Lance Bass and Richard Chamberlain, but by this point it’s all far too late. The film spends too much time revelling in the prejudice and ignorance of its small-minded characters and the closing scenes in support of gay rights are simply designed to undermine much of the preceding homophobic bigotry and offer the film moral redemption.

AUNTY:

‘What are you drinking?’

SEAN:

‘Bourbon and coke’

AUNTY:

‘The very drink Tallula cried out for on her deathbed!’

Aunty and Sean in The Fluffer

Whatever the case, to rain on Sandler’s parade, the makers of Chuck & Larry were accused of plagiarism by the producers of Australian film Strange Bedfellows (2004) who thought the plot of Chuck and Larry was all too familiar. Shana Levine, one of the producers of the Aussie film, said legal action was being considered after expert analysis of the two scripts found striking similarities. Strange Bedfellows, starring Paul ‘Crocodile Dundee’ Hogan and Michael Caton, was a comedy about a widowed businessman who weds his widowed friend in order to take advantage of new tax breaks. It was certainly very similar and had the same matey vibe running throughout, the same rather corny, clichéd comedy and that same warm undercurrent creeping up on the audience at the end.

By the end of 2007, it was quite satisfying to hear the nominations for the worst films of the year announced. Not surprisingly, Sandler’s attempt to make a comedy film about gay marriage made it to the Golden Raspberry Awards shortlist. I Now Pronounce You Chuck & Larry was nominated in eight categories including Worst Film, Worst Actor (Adam Sandler), Worst Supporting Actor (Kevin James), Worst Supporting Actress (Jessica Biel) and Worst Screen Couple (Sandler and either James OR Biel), Worst Screenplay and Worst Director!

But away from these inconsequential, fluffy movies, some filmmakers were getting down to the nitty-gritty. As the new millennium lit the horizon in a glow of possibility, more subtle, cutting-edge works began to emerge. Everything from Punks (2000), Patrik-Ian Polk’s comedy of life among African-American gay men; Before Night Falls (2000), Julian Schnabel’s biopic of the late gay Cuban author Reinaldo Arenas; Curtis Hanson’s Wonder Boys (2000), with Robert Downey Jr bedding Tobey Maguire; By Hook or By Crook (2001), Harry Dodge and Silas Howard’s lesbian/transgender buddy film; and Moises Kaufman’s The Laramie Project (2002), which recounted the horrific 1998 bashing death of young gay man Matthew Shepard in the small Wyoming community dubbed the ‘hate capital of America’. In fact, The Laramie Project was particularly groundbreaking in its style, mixing real news reports with actors portraying friends, family, cops, killers and other Laramie residents using their own words. Kaufman’s film followed Matthew’s visit to a local bar, his kidnap and beating, the discovery of him tied to a fence, his death and funeral, and the trial of his killers. It was a harrowing, moving and hugely important monument to a dark day in recent history that we should never forget.

Michael Cuesta’s L.I.E. was another quality release. An unsensationalised drama of intergenerational gay love, it emerged a critical winner at Sundance in 2001. The film had Brian Cox in the role of Big John Harrigan, a guy who feels the love that dares not speak its name, but expresses it through seeking out adolescents and bringing them back to his pad. But John is an even-tempered, funny, robust old man who actually listens to the kids’ problems (as opposed to their parents and friends, who are too caught up in the high-wire act of their own confused lives). He’ll have sex-for-pay with them only after an elaborate courtship, charming them with temptations from the grown-up world. Undoubtedly a powerful, intensely moving drama, Brian Cox, speaking on its release, was right to be proud to be part of it: ‘It’s a rites-of-passage story that any 15-year-old would identify with,’ he explained. ‘It’s about sexual awakening and whether one is gay or straight. This film is meant to unsettle and, I think, that is what drama at its best does. At its best, it throws questions at you. At its best, it puts things into the ring for debate. That’s why I am very proud of this film.’

‘I think you are just like James Bond except James Bond doesn’t go around blowing boys.’

Howie in L.I.E.

Based on a play by Daniel Reitz, Urbania (2000) was another gay-interest gem discovered at Sundance. Jon Shear’s dark psychological thriller had a wonderful sense of style and toyed with audience expectations, treading the thin and often ambiguous line between the real and imagined. The main storyline centres on Charlie (Dan Futterman), a gay man who has recently suffered through the traumatic end to a meaningful relationship. Charlie pines for his ex, making rambling, pleading phone calls to answering machines and languishing in his now-too-big bed, his hand lingering on the empty pillow beside him. He roams the rainy downtown streets encountering urban legends come to life everywhere, from the lady who microwaves her poodle to the man who gets a nasty surprise the morning after a one-night stand. In Urbania, it’s difficult to tell the truth from sorrowful, wishful-thinking fantasy. And that’s probably the point.

Big Eden (2000) wasn’t anywhere near as dark as Urbania but it attracted as much attention, winning the audience awards at just about every gay and lesbian film festival there is. Thomas Bezucha’s film had Arye Gross as Henry, an artist living in New York but still carrying a torch for the guy he had a crush on in high school. When his grandfather has a stroke, Henry returns to his Montana hometown, Big Eden, where he rediscovers friends he hasn’t seen in years. His high-school crush has since married, had children and divorced – and seems ready to take some very different steps with his life.

Eric Schweig and Arye Gross in Big Eden(2001)

Writer-director Bezucha made sure he deviated from the elements that typically punctuate gay films: ‘The thing that infuriates me or is offensive to me about the attitudes of distributors or the industry is they so underestimate the breadth of gay experience and the types of films gay people want to see about themselves. That was really important to me in terms of making this film – gay people come in all shapes, all sizes, all colours. If you looked at the history of gay cinema in the last few years you wouldn’t know that. You’d think everybody was about 20 years old and goes to the gym three times a week. I really wanted to reverse that notion and see the kinds of people I know on the screen – people who are close to their families, or go to church, or work with children and have relationships with straight people – to show that gay people are just like everybody else.’

Bezucha succeeded in his mission to tell a more true-to-life gay story. His uniquely American fable is more than just a crowd-pleaser with pretty mountain location scenery – it’s a genuinely funny and moving romantic comedy, without a single syrupy moment.

The Fluffer (2001) was another American indie that got people talking. A triangular story of obsessive love set against the backdrop of the adult-video industry, the film featured cameos from a number of figures in the adult-entertainment industry, including Ron Jeremy, Chi Chi LaRue, Karen Dior, Zach Richards, Derek Cameron, Chad Donovan, Thomas Lloyd, Jim Steel and Cole Tucker.

Scott Gurney in The Fluffer(2001)

Meanwhile, John Cameron Mitchell’s transsexual rock musical Hedwig and the Angry Inch (2001) appeared with a cult status already established. Beginning life in 1997 as an off-Broadway musical, Hedwig tells the story of an East German boy named Hansel who grows up gay, falls in love with a US master sergeant and wants to go to America with him. The master sergeant explains that, as Hansel, that will be impossible, but if the lad undergoes a sex-change operation, they can get married and then the passport will be no problem (‘To walk away, you gotta leave something behind’). Filmed with ferocious energy, it was no surprise when the movie quickly spawned a small Rocky Horror-like cult following, with midnight screenings, or ‘shadowcasts’, where fans dress up as the characters and sometimes act out the dialogue or talk back to the screen.

Another quirky release came in the form of a ‘mockumentary’, Showboy (2002), with cameos by Whoopi Goldberg, Siegfried & Roy, Alan Ball and the cast of the television series Six Feet Under. The movie centres around a closeted guy called Christian Taylor who is talked into being the subject of a British television documentary series about English writers working in Hollywood. It won Best Directorial Debut at the British Independent Film Awards and Best Film at the Milan International Film Festival.

Everett Lewis’s Luster, a film about the lives of a group of friends in the queer punk scene, was also of note in 2002, as was Brad Fraser’s Leaving Metropolis, a Canadian drama about a gay man and a married heterosexual man who fall in love.

Happy Birthday (2002) was another indie drama of intense poignancy and emotional power that won praise from critics and audiences. Taking some ensemble tips from Robert Altman, Yen Tan’s film traced the lives of five people who share the same summer birthday. Jim, a gay, overweight telemarketer (for a weight loss programme) faces his self-esteem issues. Ron is a minister who preaches about conversion but practises watching gay porn whenever he can. Javed, living in the US with a gay porn actor, faces deportation as a Pakistani and condemnation from his Islamic family. Kelly, a young lesbian, weathers a break-up with her lover and considers an earlier unrequited love. And Tracy, an Asian lesbian, goes back in the closet when her mother visits.

Shot on DV, Tan’s black-and-white movie is remarkably filmic, much of it framed in stark wide shots. It was different because it successfully captured a diverse group of people at various stages of their gay lives in a way that many gay films have not been able to accomplish.

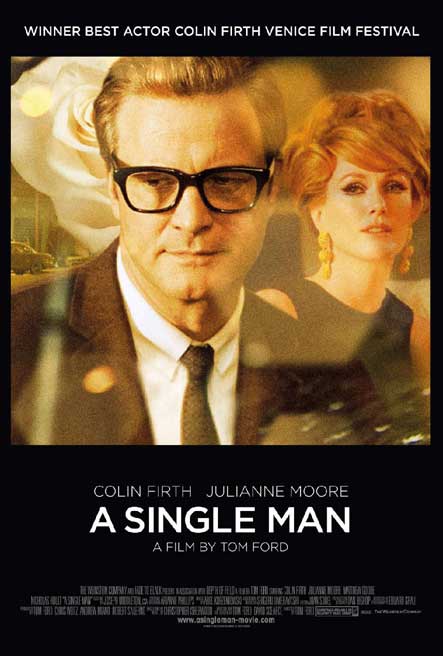

Also appearing in 2002 was acclaimed director Todd Haynes’ most mainstream movie to date, Far from Heaven, for which he recreated a 1950s weepie, depicting a gay man coming to terms with his sexuality. The film, starring Julianne Moore and Dennis Quaid, was nominated for four Academy Awards as well as winning 71 other awards and being nominated for another 30.

Stephen Daldry’s The Hours (2002) was another film nominated for lots of Oscars. Based on the novel of the same name by out gay author Michael Cunningham, the film explored the parallel lives of three women from different eras (played beautifully by Nicole Kidman, Julianne Moore and Meryl Streep), all in some way dealing with underlying suppressed homosexuality. Most praise was heaped upon Kidman for her role as Virginia Woolf. In the middle of writing her book Mrs Dalloway in 1923 England, she is coming to the realisation of her lesbianism and fighting her pure despair at life. Kidman walked away with the Best Actress Oscar. The second strand to the movie is set in 1951 Los Angeles where Laura Brown (Julianne Moore), a pregnant housewife, is planning for her husband’s birthday, but is preoccupied with reading Woolf’s novel. Meanwhile, in 2001 New York, Clarissa Vaughan (Meryl Streep) is a lesbian publisher planning an award party for her friend, an author dying of AIDS (Ed Harris, nominated for Best Actor in a Supporting Role). Taking place over one day, all three stories are interconnected through Mrs Dalloway: one is writing it, one is reading it and one is living it.

In 2003, Christopher Munch tackled a rather difficult subject area in his movie Harry and Max, about two brothers who are also lovers. Harry is a 23-year-old ex-boyband member whose solo career is drying up while Max is his 16-year-old brother whose music career is on the rise. A lot of hype surrounded the film, which premiered at Sundance, mainly because the two main characters are supposedly based on Nick Carter of the Backstreet Boys and his brother, Aaron Carter. This was never confirmed or denied by the film’s makers. Unfortunately, what could have been a serious, interesting look at a controversial subject turned out to be so amateurish and full of psychobabble that it was utterly disappointing.

Christopher Munch’s Harry and Max(2003)

Also in 2003, playwright Tony Kushner adapted his political epic Angels in America, about the impact of AIDS on the gay community, for the quality TV network HBO. The result was one of the most thought-provoking, visually beautiful pieces of work ever seen. The drama encompasses so much – it’s a story about loneliness, friendship and family, biological and chosen; about sexual, racial, religious, ethnic and political identity; about life in the Reagan era and living with – and dying from – AIDS. Tony Kushner’s writing is, as always, exceptional and Mike Nichols’ direction impeccable. There are eight flawless principal performances, and a Michelangelo-like team of production designers. Despite being originally shown split into a miniseries on American television, Angels in America has subsequently been played at festivals as an amazing epic continuous piece. On DVD, the episodes are divided into chapters which can be watched continuously without interruption.

‘Greetings, Prophet! The great work begins! The Messenger has arrived!’

The Angel in Angels in America

Rodney Evans’ Brother to Brother (2004) was another interesting work to emerge, a drama about the struggle of being young, black and gay. An ambitious film, comparing and contrasting post-millennial gay angst in the black community with the audacious sensibilities of the Harlem Renaissance, it seemed to have the same urgency of those early 90s new queer movies. With a bigger budget and a sharper focus, it might have fared better.

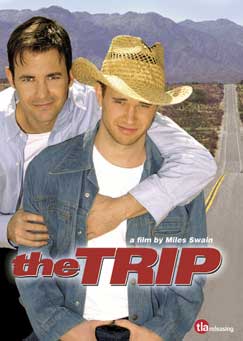

Meanwhile, Latter Days (2003), a rather unique, unexpected love story between a West Hollywood party boy and a closeted gay Mormon missionary, was sweet and sexy but more ambitious than most of the early-2000s fluffy romance flicks, as was Miles Swain’s epic romance The Trip (2002).

The Trip told the love story of two very different gay people – an activist called Tommy and a closeted journalist called Alan – over a 30-year span, from the 1960s to the 1980s. Whereas most recent gay rom-coms have had little substance, The Trip had attitude and took a few more risks. Interspersed among the scenes are documentary sequences of the highlights and low-lights of the gay-rights movement: Harvey Milk’s rise and fall, Anita Bryant’s infamous anti-gay crusade, Gay Liberation, AIDS. It’s the kind of gay social history that has rarely been attempted in film.

A ‘gay party culture’ movie seemed to emerge in the new millennium, too, with various films set in the sex-and-pecs, music-and-steroid world of the party scene – where drugs flow and inhibitions fall away on the sweaty dance floor. Circuit parties are usually held in major cities like Los Angeles and Miami, or resort destinations such as Fire Island and Palm Springs, attracting thousands of people. Created in the 1990s, ostensibly as fundraisers for gay and AIDS organisations, in time these parties took on their own identities as weekend-long extravaganzas and gay men would travel from one to the next, creating their own subculture. Dirk Shafer’s Circuit (2001) was a sizzling saga of life inside this sexy and dangerously seductive area of the gay world. With actual circuit party footage and mounds of glistening and chiselled flesh, the pulsating film focused on a character called John, a gay Midwestern policeman who has moved to Los Angeles to experience the freedom that circuit parties offer. Guided by a beautiful but ageing hustler who lives only for his next high, John realises that although many find pleasure, escape and healthy recreation in this fast-paced world, others are not so lucky. Passionate about the filmic potential of circuit parties, Dirk Shafer knew the world intimately: ‘Because circuit parties started out as AIDS fundraisers, I knew it was a controversial, provocative subject matter to depict on film. I wanted to show both sides of the circuit phenomenon – the light and the dark side. When Gregory Hinton and I developed the story, we initially aspired for the edge of Boogie Nights and Trainspotting. Later we decided that too strident a portrayal wasn’t fair to the majority of gay men who attended. Circuit parties can be many things to many people, as the film depicts.’

‘I have sex with men. But unlike nearly every other man of whom this is true, I bring the guy I’m screwing to the White House and President Reagan smiles at us and shakes his hand.’

Roy Cohn in Angels in America

The key to the success of Circuit was the filmmakers’ ability to film at actual circuit parties, opening the movie up to some thrilling visuals. A year after Circuit premiered, documentary makers Stewart Halpern and Lenid Rolov went a step further with their true-life film When Boys Fly (2002), which followed a group of men to the Palm Springs White Party. After a series of auditions, four men were selected with varying degrees of experience in the circuit. The cameras then followed them and their friends as they experienced the full range of highs and lows of the scene, from creating friendships to suffering drug overdoses. The groundbreaking film offered a true insider’s view of a world that few actually see.

Both Circuit and When Boys Fly dared to show what modern gay life is all about, warts and all, and were a welcome change from all the feelgood romantic fantasies and love stories that would never happen in a million years. The filmmakers responsible for Circuit and When Boys Fly were telling real stories. They were trying to tell the truth.

In Britain, it was left to television dramatists to come up with realistic depictions of the current UK gay party-hard lifestyle. Rikki Beadle-Blair’s Metrosexuality (2001) was a hip, energetic series that offered up a vivid take on the sexual and mating dilemmas of today. Meanwhile, Russell T Davies’ second series of Queer as Folk (2000) continued a story more important than most on our movie screens, that of Stuart and Vince, two Canal Street regulars just starting to think about where their lives may be going. The excellent follow-up to Davies’ original landmark series was darker, had more of an edge and seemed even more grounded in the realities of modern gay life than the earlier episodes. Queer as Folk 2 spoke more emotional truth than any recent narrative film about gay life and, if the two-parter is watched back to back, it stands alone as a feature of its own.

Seth Green and Macaulay Culkin in Party Monster(2003)

Another film based around party culture saw Macaulay Culkin’s return to the screen after a nine-year absence. In Party Monster (2003), he played fresh-faced Michael Alig, the real-life gay king of New York’s ‘Club Kids’, a group of young, costumed, party-obsessed carousers who ruled the city’s nightlife in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The film explored how Alig rose to fame, launched his own magazine and music label, then fell into a drug-fuelled downspin and eventually murdered his live-in dope dealer.

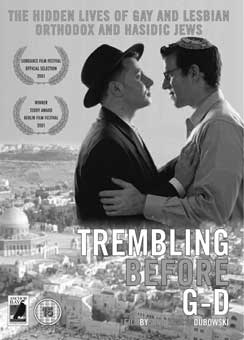

As well as fact-based thrillers, there were various documentaries made during this decade: Southern Comfort (2001), an account of love and death among trans people; Trembling Before G-d (2001), which detailed stories of lesbian and gay Orthodox and Hasidic Jews; The Cockettes (2002), a lively history of the seminal San Francisco performers; and Andrew and Jeremy Get Married (2004), an intimate portrait of two Englishmen from vastly different social backgrounds dealing with the ‘ups and downs’ of their eccentric relationship.

This decade saw some notable lesbian-interest cinema entries, too. Set in Paris and starring two of France’s most exciting new actresses, The Girl (2000) was a gorgeously realised modern film noir, following a spiralling affair between the film’s narrator – a beautiful painter (Agathe de la Boulaye) – and a nightclub singer whom she calls The Girl (Claire Keim). Sande Zeig’s film was a fascinating look at obsessive love, as was Lea Pool’s Lost and Delirious (2001), a story about the friendship of three schoolgirls and how they experience life and love together at a private college. Based on the novel The Wives of Bath by Susan Swan, the story is about a love deeper than sexuality; it’s about the quest for real true love and this theme is obviously close to the director’s heart.

Benzina (2001) was another moody, modern lesbian film noir, following the story of two lovers living in a remote petrol station, with their blissful lives giving way to desperation and the need to escape. While Benzina was kind of Thelma & Louise meets Bound, Sharon Ferranti’s Make a Wish (2002), on the other hand, was more Friday the 13th. In the tradition of classic slasher films, this movie revolved around a group of lesbian ex-lovers camping in Texas and had all the blood, gore and suspense you’d expect in a horror movie.

Benzina(2001)

By far the most mainstream and successful lesbian interest movie, however, came in the Hollywood studio-produced Kissing Jessica Stein (2001), a sharp rom-com about two women so fed up with the dating scene that they decide to go out with each other. It’s not really about lesbian lifestyles but it’s a fairly witty take on change, risk and romance, although let down slightly by the general sitcom-type feeling to the whole thing. It’s present in a lot of recent comedies, that Friends/Will & Grace set-up. And this also happens to be set in that kind of glossy New York world. But the film had its merits and came with the same feelgood factor as other female-focused dramas such as Fried Green Tomatoes (1991) and The Joy Luck Club (1993). Interestingly, the two women who starred in Kissing Jessica Stein (Jennifer Westfeldt and Heather Juergensen) also wrote the screenplay.

Another romantic lesbian-themed comedy of the fluffiest kind was Puccini for Beginners (2006), Maria Maggenti’s long-awaited follow-up to her 1995 indie hit The Incredibly True Adventure of Two Girls in Love. It was another Manhattan-set comedy, this time about a neurotic writer who has simultaneous affairs with the male and female halves of a recently split couple. However, like Kissing Jessica Stein, there was nothing especially original going on, and the laughs were often minor. Although borrowing from the devices of vintage Woody Allen, the result was more a cutesy sitcomised jaunt through the Big Apple, L-Word style.

Maria Maggenti’s Puccini for Beginners(2006)

The Gymnast (2006) was a runaway hit on the LGBT festival circuit, capturing the Jury Award for Best Feature at New York’s NewFest, the Audience Award for Best Feature at Frameline (San Francisco’s queer film festival) and the Grand Jury Award at Outfest in Los Angeles. In fact this lesbian-interest movie – which can be enjoyed by anyone – was the winner of more than 20 awards at gay (and straight) film festivals worldwide. The feature-length directorial debut from Ned Farr, it was the story of 40-something Jane (Dreya Weber of Lovely & Amazing), trapped in a lifeless marriage, working as a massage therapist and forever lamenting an accident which nixed her potential as an Olympic hopeful. That is, until she begins training for a Vegas-style revue with a beautiful Korean gymnast named Serena (Addie Yungmee). With standing ovations from most audiences, as the emotional final scenes play out over the end credits, it’s clear that The Gymnast has been simply one of the best, and most well-received, lesbian-interest movies of recent years.

Ned Farr’s The Gymnast(2006)

British cinema began the decade with some interesting gay-themed movies. Originally made by the Scottish Television Network, Forgive and Forget (2000) was a love-triangle drama that finally emerged as a full-length theatrical release. Starring Brit-packers John Simm, Laura Fraser, Steve John Shepherd and Meera Syal, the story centred around long-time best friends David (Shepherd) and Theo (Simm) who find their relationship strained when Theo falls for a woman and moves in with her. David is forced to face his biggest secret – he’s gay.

Forgive and Forget presented its story without relying on major stereotypes (here, the gay guy was a plasterer), which made it all the more powerful and a movie which both gay and straight audiences could relate to.

Movies set in the criminal underworld have invariably been suffused with homoeroticism and Endgame (2001) was no exception. A moody, stylish and sex-charged British thriller, it starred Daniel Newman as Tom, a rent boy kept in style by sado-masochistic gangster George Norris (Mark McGann). Sucked down into a nasty scheme involving drugs, money and protection by Norris’s connection with a crooked gay cop, Dunston (John Benfield), things turn nasty rather quickly for Tom in Gary Wicks’ fast-paced thriller. With a striking soundtrack and excellent acting Endgame is one of the better gay gangster thrillers released in the last decade.

‘We won’t die secret deaths anymore. The world only spins forward. We will be citizens. The time has come.’

Prior Walter in Angels in America

A rent-boy plot strand also featured in AKA (2002). Set in Thatcher’s Britain, it was the gripping story of Dean (Matthew Leitch), a shy, working-class lad from Romford, kicked out by his abusive father. The film, based on a true story, followed Dean’s move to London and a new life of deception and duplicity, rent boys, toffs, artists, champagne and coke. Duncan Roy’s film was a mesmerising study of the British class system, a modern-day Pygmalion. It also garnered the director a BAFTA nomination.

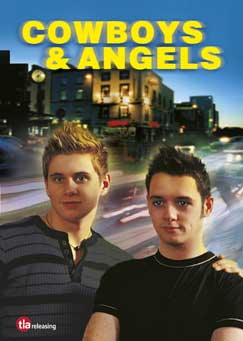

Meanwhile, from Ireland, came Cowboys & Angels (2003), a drama about life in the big city, centred around gay boy and straight boy, although here all is out in the open. The movie has Shane (Michael Legge), a shy civil-service worker moving into a Limerick apartment with Vincent (Alan Leech), a gay fashion-school student who goes out to clubs and picks up guys on a regular basis. Vincent goes all Queer Eye on his awkward flatmate, trying to help him adapt to his new surroundings with, amongst other things, a makeover. Another film that should be praised for its non-issue treatment of sexuality, Cowboys & Angels took an important step towards movies where ‘straight’ and ‘gay’ don’t matter so much as ‘relationships’.

Also from Ireland, in 2003, came a rather different approach to a gay-themed movie. Offensively funny, politically correct and in your face, 9 Dead Gay Guys told the story of Kenny (Glen Mulhern) and Byron (Brendan Mackey), two Irish lads who’ve moved to London in a bid to hit the big time. But the straight mates end up hustling for beer money at the local gay pub and before the end of the film there are nine dead locals. It was a dark comedy in the John Waters tradition but doesn’t really cause much offence. In fact, it’s a good example of a crossover movie with both gay and straight audiences connecting with it.

‘New York is where everyone comes to get fucked.’

Tobias in Shortbus

In Canada, adapted from his stage play Poor Superman, Leaving Metropolis (2002) marked the directorial debut of screenwriter Brad Fraser. It was the story of David (Troy Ruptash), a successful gay artist who falls in love with a married ‘straight’ guy. Within this erotic exploration of the fluid nature of sexuality and gender identity, Leaving Metropolis featured a scene-stealing performance by Thom Allison as David’s transgendered, HIV-positive friend and roommate, Shannon. The film fared well at festivals around the world.

Whole New Thing (2005), also from Canada, was the winner of 11 awards at lesbian and gay film festivals around the world. Set in a remote part of Nova Scotia, it was a funny, intelligent take on teenage sexuality centring around 13-year-old Emerson (Aaron Webber), home-tutored all his life by his hippie parents and now finding it hard to fit in at his local high school. An openly gay English teacher (Daniel McIvor) tries to give the boy some helpful advice, but is totally unprepared for a daring (and dangerous) response. Despite the subject matter, director Amnon Buchbinder made a film of admirable purity and one full of heartache.

Thailand produced a couple of interesting gay-interest movies in the early part of the decade. The Iron Ladies (2001) was a lively and often hilarious comedy about an all-gay volleyball team who, against all odds, make it to the national championships against increasing opposition. Queeny and camp, an uplifting gay classic, the film would be almost too heartwarming if it weren’t a true story. The largest-grossing Thai film of all time, it was no surprise when director Youngyoot Thongkongtoon recently made a sequel based upon how the characters in Iron Ladies met, and how they would later reunite for another volleyball tournament.

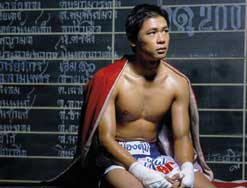

Ekachai Uekrongtham’s Beautiful Boxer(2004)

Also from Thailand came Beautiful Boxer (2004), a warm, funny, action-packed film about the experience of being transgender, based on the true story of Nong Toom (Asanee Suwan), a poor boy from rural Thailand whose only hope of raising the money to pay for a sex-change operation was to enter the ring as a professional kickboxer. Which is what he did, winning fight after fight, and humiliating his macho opponents in the process.

South Korea has only recently taken homosexuality off its list of ‘unacceptable social acts’, and soon afterwards this conservative country picked a gay-themed production as its Foreign Language Film submission for the Oscars. The King and the Clown (2005) was a surprise hit in South Korea, selling over 12 million tickets. Lee Joon-ik’s film is set in the court of a mad king and centres around a love triangle involving an attractive young jester.

Auraeus Solito’s The Blossoming of Maximo Oliveros (2005)

Staying with Asian cinema, The Blossoming of Maximo Oliveros (2005) was a great film from the Philippines by first-time director Auraeus Solito. Winning the 2006 Teddy award at the Berlin Film Festival, Solito pulled off an assured and delightful work, set in the backstreets of Sampaloc, a poor district of Manila, with the lead character, Maximo, a self-confident, 12-year-old boy with a penchant for dressing up and a clear sense of his own gay identity. Sashaying around the neighbourhood with no problems, helping his widowed father and two brothers run the household, Maximo soon falls in love with a young policeman, and the scene is set for a dramatic conflict of loyalties. This bitter-sweet tale of adolescence captured the hearts of audiences around the globe, managing to handle the notion of prepubescent sexual anxiety with intelligence and unflinching honesty. Solito’s film revealed a style of gay life which has rarely been explored on the screen – and for that it was rightly praised.

Israel produced a winner, too – in Yossi & Jagger (2002). Originally produced for Israeli cable TV, it was a gorgeously directed, tender drama about two Israeli soldiers who fall in love while serving in a remote military outpost on the Israeli-Lebanese border. Commanders Yossi (Ohad Knoller) and Jagger (Yehuda Levi, one of Israel’s biggest heartthrobs) develop an intensely romantic connection which is unknown to almost all of the base’s other occupants and visitors. Although gays have been allowed to serve in the Israeli military since 1985, the film showed how homophobia still manages to permeate society on all levels. Featuring a stirring, heart-wrenching climax, Yossi & Jagger ended up a theatrical box-office smash at home and was one of the most emotionally moving gay films of 2003.

French cinema produced a string of gay-themed films this decade. The Closet (2001) was French farce in the tradition of Molière: a man pretends to be something he’s not, people begin treating him differently, his lie escalates out of all proportion, and comedy ensues. Francis Veber’s film centred around François Pignon (Daniel Auteuil), a sweet-natured if slightly dull divorced accountant who discovers that the best way to save his job and appear more interesting to his workmates is to pretend he’s just come out of the closet – even though he’s straight. Starring alongside Auteuil was Gérard Depardieu, playing the office manager, a rugby-playing brute, forced to swallow his homophobic views and explore his feminine side. Boasting some sharp satire, lampooning current political correctness, Veber’s comedy played merry havoc with sexual politics and the social commentary built to an unashamedly feel-good climax.

Originally created for French television, Fabrice Cazeneuve’s 2002 film You’ll Get Over It (A cause d’un Garcon) covered all the bases of a contemporary coming-out story: the lying, the betrayal, the shock, and the locker-room homophobia. Set in a suburban Paris high school, the drama followed popular athlete, Vincent, who, constantly struggling with the secret of his homosexuality, runs off to Paris for a rendezvous with an older man, while back at home a strict code of silence is in effect. Unfortunately, Cazeneuve’s film didn’t really have anything unique to distinguish it from other coming-out or coming-of-age dramas.

Novelist-playwright Christophe Honoré stepped into filmmaking in 2002, with Close to Leo, a sensitive and realistic look at a rural family coping with AIDS. Intriguingly, the story was told from the point of view of the curious and precocious 12-year-old Marcel (Yaniss Lespert), who knows his family is keeping something from him. Honore’s film is energetic and very honest, with some superb performances, and it deservedly became an international festival classic.

Patrice Chéreau’s Son Frère (2003)

Son frère (2003) was even more downbeat than Ma vraie vie à Rouen. Patrice Chéreau’s film centred around two estranged brothers, brought together when one is diagnosed with a rare blood disease. Reunited, they go on to learn about life, love, acceptance and all that stuff, amidst all the taboos found in many French art-house films: incest, homosexuality, suicide, infidelity, male nudity, and so on. Adapted from a novel by Philippe Besson, the film was an unsettling and unusual affair, consciously slow and sombre, in the director’s words: ‘A film about bodies, about the degradation of one body, about how one faces change.’

France seems to have embraced digital video technology wholeheartedly, and Ma vraie vie à Rouen (2002), by the directing duo Olivier Ducastel and Jacques Martineau, who made the gay road movie Drôle de Felix two years earlier, is one example. Their film, about a teenager’s sexual awakening, is structured like a video diary, with 16-year-old virgin Etienne (Jimmy Tavares) making confessions to the camera. The format isn’t an easy one to get used to, as events take shape very subtly, but the directors struck a careful balance between improvisation and directorial control, deliberately avoiding turning the film into a parody of ‘reality TV’.

A few years later, Ducastel and Martineau’s next gay-interest film, Cockles and Muscles (2006), was much more light-hearted. A pleasurable comedy of love and sexual identity, it was a tale of the intricacies of modern French family life, set in a seaside resort on the Côte d’Azur. A holidaying family – husband and wife Marc and Béatrix, their teenage son, Charly, and his friend, Martin – set themselves up for a string of sexual revelations, all served with oodles of saucy French humour and moral tolerance. The film culminated in what Ducastel and Martineau call a ‘number of blissful unions and song’, a truly spectacular camp ending. It was all good fun but obviously nowhere near as interesting as earlier Ducastel and Martineau films.

Also from France, and certainly worth a mention, is the documentary Beyond Hatred, released in 2006. French docmaker Olivier Meyrou spent time with the family of François Chenu, a gay man murdered by three skinheads in 2002, and through conversations with François’s parents, schoolteacher Jean-Paul and hospital caregiver Marie-Cecile Chenu, the family’s chain-smoking female lawyer and others, the main facts of the case emerge. The point of the film was not to explore the homophobic attack itself, but its aftermath. The Chenu family’s feelings are documented, as they evolve from anger and despair towards an almost saintly recognition of how the killers’ own deprived backgrounds led them to this horrible act. The father of one of the killers, an alcoholic who tried to destroy evidence, and another attacker’s aunt were also interviewed and treated with the same even-handed sympathy by the filmmakers, helmer Meyrou and his crew, who were invisible throughout, in classic vérité style, and refused to spell things out via explanatory subtitles or narration.

Most recently from France, Franck Guérin’s Un jour d’été (One Day in Summer) (2006) was a film that tried too hard to cover a number of genres: a coming-of-age movie, a family drama, a tale about the loss of a friend. It’s all there in rather an unfocused muddle of a movie, about the death of a soccer goalie named Mickaël (Théo Frilet) and what happens to his small town after he dies. Other directors, like Christophe Honoré, fared better (Close to Leo is just one example).

From Italy came an occasionally moving if ultimately familiar soap opera, La fate ignoranti (2001), a film from Italian-Turkish director Ferzan Ozpetek, who directed Steam: The Turkish Bath (1997). The film concerned a man’s secret gay life uncovered by his grieving widow and, although it was quite refreshing, it was altogether too fluffy.

Ferzan Ozpetek’s La fate ignoranti(2001)

The Best Day of My Life (2002) was a box-office hit in Italy when it opened. Cristina Comencini’s film was a portrait of a rich Roman family – matriarch Irene (Virna Lisi) and her grown-up children: two daughters, Sara (Margherita Buy) and Rita (Sandra Ceccarelli), and a gay son, Claudio (Luigi Lo Cascio). Almost everyone is forced to confront love, sex and fidelity in what was a compelling story of three generations and their moral choices. The film became the surprise winner of the Grand Prix of Americas, the top prize at the Montreal World Film Festival.

Romance radiated throughout the various Spanish entries in gay cinema this decade. Km. 0 – Kilometer Zero (2000) took its title from a popular meeting place in Madrid’s central plaza, the Puerta del Sol, and followed a series of chance meetings, missed connections and mistaken identities that give way to erotic interludes, sexual escapades and romantic couplings. From a fresh-faced aspiring director involved with a prostitute, to a gay dance instructor whose computer sees more action than he does, to an older woman seeking a male escort for the first time, Km. 0 was fast-paced, inventive and stylish – but not quite Almodovar.

Meanwhile, interestingly, the famous Spanish director Ventura Pons chose to film his 2002 movie Food of Love in English, with an English cast, even though the entire production was Barcelona-based. His meticulous adaptation of David Leavitt’s novel The Page Turner was a highly moving account of an inexperienced gay teenager who falls for an older concert pianist and it won rave reviews at the Berlin Film Festival.

‘My body may be a work-in-progress, but there is nothing wrong with my soul.’

Bree in Transamerica

Cesc Gay’s stunning Spanish coming-of-age story, Krampack (2001), cut from similar cloth as Beautiful Thing and Get Real, detailed the sexual awakenings and experimentations of two teenaged boys during a summer holiday on the sun-baked Spanish coast. The virginal boys, Dani (Fernando Ramallo) and Nico (Jordi Vilches), spend time with two girls of their age, but Dani’s feelings for his best friend are clouded with unspoken desire, and when the occasional night-time ‘krampack’ (mutual wank) fails to satiate Dani’s appetite, the friends slowly drift apart. Writer-director Gay thankfully refused a happy-ever-after ending, opting for a more ambiguous conclusion.

Also from Spain, in 2003, came the comic and darkly romantic thriller Bulgarian Lovers, the film that marked the long-awaited return of the pioneering Spanish gay filmmaker Eloy de la Iglesia. With its themes of love, money and lust, the film was an almost surreal journey through the life of the loveable Daniel (Fernando Guillén Cuervo), a wealthy, spoilt, middle-aged but attractive businessman whose ordered life is thrown into a tailspin when he meets Kyril (Dritan Biba), a sexy, muscular beauty with a charmingly cute smile and a covert life.

German cinema produced the melodramatic coming-out tale Summer Storm (2004), set at a summer rowing camp in idyllic countryside where a talented teenage oarsman, Tobi (Robert Stadlober), is struggling with his feelings towards best friend and team-mate Achim (Kostja Ullmann). A kind of German Beautiful Thing, Marco Kreuzpaintner’s film covered old territory in lessons on sexual tolerance and being true to one’s desires and, unfortunately, chose to end on a calculatedly uplifting climax, to the beats of a rather naff cover version of ‘Go West’.

Marco Kreuzpaintner’s Summer Storm(2004)

The Aussie film Tan Lines (2007) also had plenty of shots of buff, shirtless guys in tight trunks but, unlike Summer Storm, its story was subtle, surreal and intriguing. Something a bit different. Set on the sun-drenched beaches of Australia, Tan Lines was a sexy but angst-ridden coming-of-age romance about a cute teen called Midget Hollows (Jack Baxter) who wanders through life riding big waves and partying with surfer boys. This ‘gay surf movie’ had passion, love, laughs, sex and drugs set against the backdrop of the Pacific Ocean. Although not a perfect indie movie, it had flashes of originality from British-born director Ed Aldridge, one of them the religious images of popes and saints hanging in the bedroom that come to life in Midget’s mind, bicker in Italian and tease him about his sexuality. ‘There’s enough sperm in those sheets to make the washing machine pregnant!’ says one pope. Aldridge’s film had relatable characters without pretension or affectation, and, thankfully, no predictable Hollywood happy ending or tacky soundtrack.

Hollywood, too, however, can go gay without resorting to tacky soundtracks. 2005 saw the release of Brokeback Mountain, Ang Lee’s epic, passionate and beautifully executed ‘gay western’ about two young men – a ranch hand and a rodeo cowboy – whose 20-year bond to each other proves stronger than either of their marriages. Based on a novella by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Annie Proulx, with a screenplay co-authored by Pulitzer-winner Larry McMurtry, it starred Jake Gyllenhall and Heath Ledger.

‘God, I wish I knew how to quit you!’

Jack Twist in Brokeback Mountain

After the flop of Alexander (2004) – which its director, Oliver Stone, attributed to the fact that America was ‘not ready to accept a romance between two men’ – many assumed it would be a long time before we saw another gay love story aimed at a mainstream audience. But Ang Lee knew better. Set against the sweeping vistas of Wyoming and Texas, his film followed the two men’s first meeting in the summer of 1963, and their subsequent lifelong connection, their relationship’s complications, joys and tragedies providing a testament to the endurance and power of love.

‘I got a boy. Eight months old. Smiles a lot.’

Jack Twist in Brokeback Mountain

Brokeback Mountain had opened at the end of 2005, a few weeks before Christmas, but in fact the whole of that year had been an amazing 12 months for gay-themed cinema and countless films with prominent gay characters.

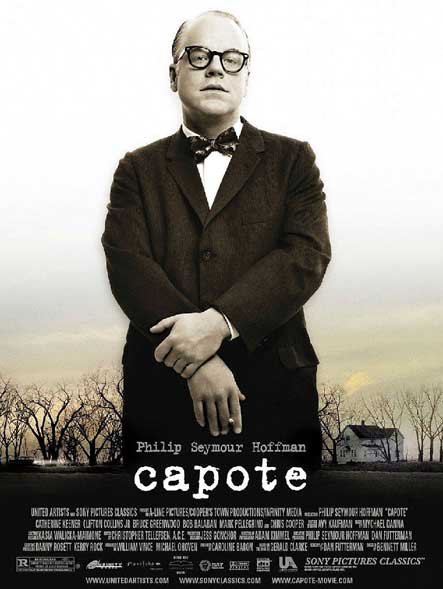

One of the twentieth century’s most celebrated – and most flamboyant – gay figures, writer Truman Capote, was played by Philip Seymour Hoffman in Capote (2005). The writer was shown with his male lover in the film, and described as having fallen in love with one of the two convicts whose story he told in the fact-based novel In Cold Blood. Strangely, a few months after Capote was made, production on Infamous (2006) began in which the iconoclastic author was played by little-known British actor Toby Jones, accompanied by a star cast including Sandra Bullock as author Harper Lee who played alongside Gwyneth Paltrow, Sigourney Weaver, Hope Davis and Jeff Daniels.

Ultimately, though, it was the earlier Hoffman film that got all the attention, which is a shame because Infamous is arguably Capote’s equal, also focusing on the writer’s relationship with convicted killer Perry Smith but dwelling more on Capote’s high-toned New York social circle. Infamous also focused more on humorous scenes in which straight-laced Kansans’ jaws drop as they react to the flamboyant and unabashedly gay cosmopolitan writer in their midst.

Douglas McGrath’s Infamous(2006)

A disturbing and challenging question was posed by director John Baumgartner in his 2005 debut, Hard Pill. If you could take a pill to make you straight, would you? This provocative independent movie starred Jonathan Slavin, in a star-making tour-de-force performance, as Tim, an unhappy gay man who decides to volunteer for a pharmaceutical study of a pill that’s said to turn homosexuals straight. Examining issues of sexuality, medical ethics and relationships of all stripes, Hard Pill was one of the best indie movies offered up in the last few years. Baumgartner’s film was a refreshingly honest and often emotionally scathing look at what a ‘cure’ for homosexuality might actually mean in the everyday lives of gay men.

Other gay-interest movies of 2005 included Kiss Kiss Bang Bang which had Val Kilmer as a gay police detective pursuing, and then teaming up with, straight petty criminal Robert Downey Jr. Meanwhile, The Dying Gaul, directed by Longtime Companion screenwriter Craig Lucas, centred around a gay writer who turns the story of his lover’s death from AIDS into a haunting screenplay, before being told by a Hollywood producer it will never be made unless he changes the gender of the dying character. Make the lovers heterosexual, says the executive, and I’ll cut you a cheque for $1 million, here and now. ‘Americans hate gays,’ he says.

Craig Lucas’s The Dying Gaul(2005)

And the mainstream gay-interest movies kept on coming. The heart-warming British comedy Kinky Boots (2005) told the truth-based story of how a provincial shoe factory on the brink of collapse resurrected itself by switching from making Oxfords for civil servants to stiletto-heel boots for cross-dressers. There was also a cross-dressing director character in the film version of The Producers (2005); a prominent gay character featured throughout Mrs Henderson Presents (2005); meanwhile, a lesbian couple, a transvestite and a gay man were central characters in Rent (2005), Chris Columbus’s film version of Broadway’s rock musical sensation.

Breakfast On Pluto (2005), based on the novel by Patrick McCabe, told the story of Patrick (Cillian Murphy) who, while growing up in 1960s Ireland, quickly realises he’s not quite like all the other boys. With an unusual fondness for sequins and eyeliner, Patrick, soon calling himself Kitten, escapes the disapproving townspeople and sets off for London in search of love and his long-lost mother.

Equally touching, Transamerica (2005) had Felicity Huffman playing a pre-op male-to-female transsexual about to have surgery to become a woman when she discovers that, years earlier, she fathered a son, who’s now a gay hustler in New York. She becomes his guardian on one very complicated cross-country trip that had audiences captivated. A remarkable film about transsexuality, Transamerica was a moving story of people seeking a sense of purpose in their lives, and finding someone understanding to share it with.

All of the above films from 2005 were popular at the box office but it was Brokeback Mountain that proved a defining film in gay cinema history. Ang Lee’s movie quickly became a cultural phenomenon and everyone – from Christians in Middle America to builders in working-class Britain – had something to say about it. Chat show hosts – David Letterman and Jay Leno in the States and Graham Norton and Jonathan Ross in the UK – parodied it endlessly, as did newspapers and magazines, including one issue of the New Yorker which had George Bush and Dick Cheney as the Brokeback heroes on its cover. The Christian brigade found it all so morally offensive, some cinema chains in certain US states banned the film and the usual groups of gay-haters organised protests.

TOBY:

‘Did you know that the Lord of the Rings is gay?’

BREE:

‘I beg your pardon.’

TOBY:

‘There’s this big, black tower, right? And it points right at this huge burning vagina thing, and it’s like the symbol of ultimate evil. And then Sam and Frodo have to go to this cave and deposit their magic ring into this hot, steaming lava pit. Only at the last minute, Frodo can’t perform, so Gollum bites off his finger. Gay.’

from Transamerica

Back in the real world, however, critics heaped praise on Brokeback and millions of cinemagoers packed out theatres to watch the gay love story. Not surprisingly, the film led the posse of gay-themed movies in the Oscars race. In fact, 5 March 2006 is the date that goes down in history as the ‘Gay Oscars’ with Hollywood actively ushering in the ‘year of the queer’.

Six awards had already gone to movies with gay or transgender characters at the Golden Globe Awards, with Brokeback roping in four, making it the firm favourite for Tinseltown’s top honours, the Oscars. However, despite its run of success at the Globes and the BAFTAs, Brokeback failed to win as many awards as hoped for at the Oscars. The film received eight nominations but was beaten to Best Picture by Crash. Neither Jake Gyllenhaal nor Heath Ledger took home gongs, with the award for Best Actor going to Philip Seymour Hoffman for his role in Capote. Brokeback did, however, come away with three awards, including Best Director for Ang Lee.

Many were surprised that Brokeback wasn’t awarded Best Picture. Most critics in the press took the line that the movie was ‘snubbed’ or described it all as ‘an upset’. In fact, historically, although movies with gay angles have earned acting honours, including Tom Hanks for Philadelphia and Hilary Swank for Boys Don’t Cry, they didn’t break into the Best Picture pack. Kiss of the Spider Woman was another example, winning an Oscar for William Hurt as a gay man but losing out on Best Picture to Out of Africa. So although Hollywood spent over three hours congratulating itself for its tolerance and progressiveness, with nominations for Brokeback, Transamerica and Capote, when it actually came to the Best Picture Award, some rather cowardly actions proved louder than pretty words.

Tellingly, before the 2006 Oscars ‘upset’, no film that had won the Writer’ Guild, Directors Guild and Producers Guild awards did not go on to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. Also, historically, the film with the most Oscar nominations almost always wins the top gong. But, strangely, Brokeback had the most nominations and yet wasn’t awarded Best Picture. Along with all these awards, Brokeback had also won the Golden Globe, all but guaranteeing that it would win at the Oscars, too. Crash did not even receive a Golden Globe nomination, for either Best Picture or Best Director.

‘You boys sure found a way to make the time pass up there.’

Joe Aguirre in Brokeback Mountain

So while the gay taboo is slowly lifting in society as well as in film, the pack of gay and transgender characters present throughout 2005 didn’t automatically mean Hollywood was ready to hand out its top awards too quickly. And Hollywood, it seems, isn’t ready to come out of the closet either. It’s interesting that not a single one of the actors who played those characters was actually gay. These straight actors are stars who ‘dare’ to take on gay roles. If straight actors can play gay parts why can’t it work the other way around?

Nevertheless, following the success of Brokeback Mountain and other studio-funded gay-themed films, mainstream filmmakers have undoubtedly been more relaxed about working in the genre of gay cinema. Boy Culture (2006), a romantic drama about the lives of a male escort and his two sexy roommates, proved a commercial and critical success, as did the even more recent release The Walker (2007), which had Woody Harrelson playing Carter Page III, a social butterfly of Washington’s political elite entertaining wealthy wives of a certain age despite the fact he also happens to be gay.

Q Allan Brocka’s Boy Culture(2006)

Even Dame Judi Dench appeared as a closeted and confused lesbian in the successful British movie Notes on a Scandal (2006), her character increasingly obsessed with the much younger female character played by Cate Blanchett. Dench’s performance was so complex and layered, however, with various subtexts and ambiguities, that she elevated the character beyond the evil, repressed, lesbian stereotype.

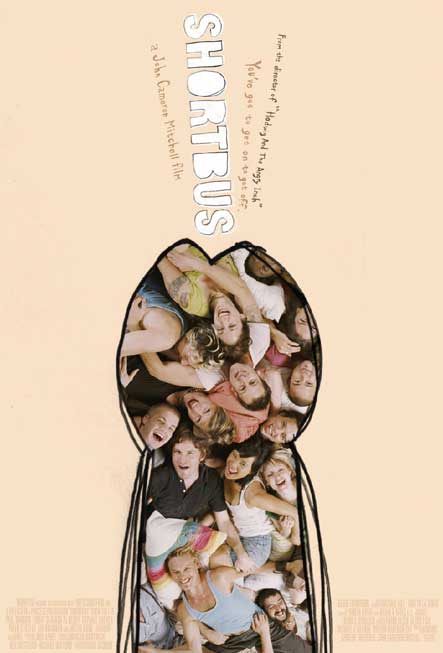

Shortbus (2006) was another key recent film, from Hedwig and the Angry Inch director John Cameron Mitchell. A subversive yet refreshingly funny and sexy gay-interest movie, it was funded by Universal Pictures and dubbed ‘the most sexually explicit film to go on general release’. The film followed various emotionally challenged New York City characters trying desperately to navigate the comic and tragic intersections between sex and love in and around a modern-day polysexual underground salon called Shortbus.

‘These people spend all night sucking cock and eating ass, and then hit the buffet claiming they’re vegan.’

Justin in Shortbus

Also in the wake of Brokeback’s success came I Love You Phillip Morris (2009) with Jim Carrey as a married prisoner who falls in love with another inmate, played by Ewan McGregor. The film itself is based on a true story (and book) which traces the plight of convict Steven Russell, whose love for Morris motivated his escape from prison four times, once by using a green pen and a bucket of water to change his prison outfit into what looked like surgical scrubs, another time by faking his death from AIDS and signing his own death certificate. Morris eventually got out, but Russell’s escapades landed him a 144-year sentence.

Another high-profile film to go into production in 2008 was Gus Van Sant’s Milk (2008). With a script by Dustin Lance Black, the biopic stars Sean Penn as Harvey Milk, the first prominent American political figure to be elected to office on an openly gay ticket, back in the 1970s. So loved was he that his brutal and homophobic assassination by ex-policeman Daniel White sparked the biggest riots in gay history.

John Cameron Mitchell’s Shortbus(2006)

Van Sant beat out the likes of Oliver Stone and fellow, openly gay director Bryan Singer, who had both been developing their own Harvey Milk projects. Singer’s The Mayor of Castro Street had a script by Usual Suspects writer Christopher McQuarrie, but was delayed in pre-production. Van Sant stepped in, got Penn on board and beat them to it. It took 30 years but thankfully Hollywood filmmakers finally got around to documenting the event which shaped contemporary gay politics in the States.

US, 95 mins

Directors: Richard Glatzer, Wash Westmoreland

Writer: Wash Westmoreland

Cast: Scott Gurney, Michael Cunio, Roxanne Day, Taylor Negron, Deborah Harry

Genre: Porn Industry drama / coming-of-age

(fluff-er, n): One who offers ego reinforcement; one who provides the necessary stimulation for a male porn star to perform

A fluffer is responsible – by hand or blow – for keeping a porn star erect. It’s a job description that was begging to be made into a movie and Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland did just that.

A self-taught filmmaker, Wash Westmoreland directed his first film, Squishy Does Porno, in 1995. It was entirely funded by tips gleaned while working at a New Orleans jazz club. The film’s unique and provocative stance made it an underground hit at many film festivals. Moving to Los Angeles, Westmoreland had the original idea to make The Fluffer, a story of unrequited love set within the modern-day gay-porn industry. Having no experience of that world, however, he decided to first do some research, and got a job directing gay porn. In just two years, not only did he write The Fluffer, but he managed to take the porno world by storm. His movie Naked Highway swept both the 1998 GV Guide and Adult Video News awards shows, receiving an unprecedented 15 awards, including best movie, best director, best screenplay, best cinematography and best sexual performance. One of Westmoreland’s porn films, The Devil is a Bottom, was the first ever adult film, gay or straight, to be included on the LA Weekly Best Films of the Year list. Westmoreland co-directed The Fluffer with his long-term partner Richard Glatzer (Grief).

Michael Cunio as Sean McGinnis

Boogie Nights is the standard against which any film about the porn industry will be measured. A more modest effort than Paul Thomas Anderson’s film, The Fluffer is nevertheless a winner and repudiated Anderson’s sentimental idea that porn performers and filmmakers are like family. This comes far closer to portraying the reality of the porn industry – the general tedium of life on set; the cheap porn sets and cost-cutting and the cynical outlooks on life. Bitterly funny, this multilayered film subverts various narrative strands – porn industry satire, unrequited love, obsession and ultimately emerges as an intelligent coming-of-age odyssey.

The story centres around three main characters: Johnny Rebel (Gurney), a gay-for-pay porn star; Sean McGinnis (Cunio), the young, naive, adventurous, and pure wannabe filmmaker who’s moved to LA to pursue his dream; and Rebel’s girlfriend, Julie Disponzio (Day), also known as Babylon, the most fiery of the dancers at the strip club, Leggs.

The film opens with a quirky porn-like twist of fate. On a trip to his local video store to rent his favourite Orson Welles movie, Sean somehow ends up with a copy of Citizen Cum.

Westmoreland’s porn-industry training is put to good use in the opening sequence of Citizen Cum, which is dreamlike and highly erotic, despite avoiding any explicit images. This serves to fetishise Johnny Rebel from the outset. Interestingly, after this mesmerising initial sequence, the porn film sequences and shoots are shown up for what they really are – an unromantic world of sterile, cheap and mostly ridiculous scenarios (pool-cleaner seduction, barnyard orgy), with corny titles (Tour de Ass and Tranny Get Your Gun).

Intrigued by Citizen Cum and, in particular, the rippling muscles of star Johnny Rebel (Gurney), Sean hunts down the production company which has Rebel under exclusive contract. He soon gets a job interview at Men of Janus (because ‘Janus was the Roman god of entrances and exits’), where vandals frequently erase the ‘J’ from the sign on the front door, and signs up for some work in order to meet the star. Sean’s love of arty compositions soon disqualifies him from camera duties. But as Johnny tends to require stimulation between takes, Sean is deployed instead as a ‘fluffer’, responsible for ensuring that the leading man is properly prepared for his explicit close-up. Sean is smitten, but the oblivious hunk is strictly ‘gay for pay’, living a heterosexual life off screen. Johnny is happy to use Sean’s services, and to be turned on by having Sean tell him how much he adores his body, but so self-absorbed he doesn’t notice that the young man is in love with him.

While Sean is completely obsessed with the icon Johnny Rebel, Babylon deals with his day-to-day reality. Sean and Babylon find it more and more difficult to cope with their roles dealing with the inhabitants of the porno underworld. In this slippery city of dreams, both try to cling to their self-respect as they go down on their knees. Babylon dreams of having Johnny’s children but Johnny only loves himself, living only for money, drugs and attention – from both women and men.

Although largely about obsession, The Fluffer is also about humiliation. Sean is very attractive and yet so nervy and vulnerable. The poster for André Téchiné’s sensitive gay drama Wild Reeds on the wall of his rented apartment marks him as a sensitive, introspective film lover, as does the fanatical monologue he delivers on the obsessive themes of Vertigo at an industry party when he’s wired on crystal meth. ‘Total porn,’ he exclaims! He has taken direct action by actually getting himself a job at Johnny Rebel’s workplace, but he still can’t get to the man he desires. He can’t get close; can’t break through the barrier of the glass screen, whether that is to the erotic images inside his TV screen or into the mirror that Johnny vainly gazes into.

Sean begins a romance with another guy called Brian (Josh Holland) but his heart is never in it and this all falls apart once it becomes obvious that all Sean can think about is Johnny. Sean even goes to Babylon’s strip-joint and pays her to give him a lap dance and confess intimate secrets about Johnny, including how he tastes and smells.

Sean’s own self-loathing and relatively closeted life is traced back – via black-and-white flashbacks – to traumatic childhood abuse. Sean’s current emotional status is mirrored by the clock on his kitchen wall, whose arms have been frozen at 9.29 since he frantically dislodged its batteries to work the remote pause button during Citizen Cum. The frozen clock remains a motif throughout the film, until a new clock far away finally chimes for Sean, relieving him of his crisis.

Johnny’s dramatic fall from grace (he kills a producer and gets Sean to drive him to Mexico) results in Sean realising how dangerous he really is. He knows he can’t stay on his knees forever. Completely heartbroken, he just about finds the courage to move on, as does Babylon. Johnny keeps on running.

The solid supporting cast features Robert Walden (Lou Grant) as a porn entrepreneur, Deborah Harry as a strip-club manager and Adina Porter as a lesbian who’s into gay-male porn. X-rated actors Cole Tucker and Ron Jeremy also show up briefly in cameos. Taylor Negron and Rich Riehle put in two of the film’s finest performances as two directors. Their jaded reactions to everything, and particularly Riehle’s repeated complaints about excessive artiness in Sean’s filming, offer some great comic moments.

The film’s soundtrack is awesome. Gay-porn director Chi Chi LaRue makes a cameo appearance leading a spirited rendition of the Joan Jett song ‘Cherry Bomb’ while the closing credits roll, accompanied by the Buzzcocks’ brilliant ‘Ever Fallen in Love’. Perfect!

Interestingly, at the time of release, the filmmakers devised a ‘Fluffer Manifesto’ which stated the following: fluffer aims to get the verb ‘to fluff’ into the dictionary by the year 2003; fluffer salutes all people who have ever been brave enough to work in the adult industry; fluffer acknowledges the tacit complicity between the worshipper and the worshipped; fluffer feels the most interesting areas of sexuality lie between definitions; fluffer sees the adult industry as exploitative only in the same way that all industries are exploitative; fluffer champions feminine aspects of sexuality; fluffer champions masculine aspects of sexuality; fluffer rails against the hypocrisy of censorship; fluffer acknowledges the link between random childhood experience and adult sexuality; and fluffer believes there is no line between art and pornography.

The Fluffer is edgy and compelling. Westmoreland and Glatzer’s hypnotic film is one of the coolest gay-themed pictures ever made. That title got butts on seats. But those who went to see the film back in 2001 were treated to a truly rich and rewarding story. If you missed out then, buy the DVD!

Michael Cunio (centre) has a Graduate moment in The Fluffer

US, 97 mins

Director/Writer: Michael Cuesta

Cast: Brian Cox, Paul Dano, Bruce Altman, Billy Kay, James Costa, Tony Donnelly

Genre: Teenage drama

Critically acclaimed as one of the top ten films of 2001, Michael Cuesta’s L.I.E. is an intense and unsettling drama about the relationship between a middle-aged man and a 15-year-old boy.

L.I.E. opens with an arresting image: a teenager is walking precariously along the railings of a footpass, with traffic thundering past underneath. His voiceover intones that ‘there are the lanes going east, there are lanes going west, and there are lanes going straight to hell’.

Set in a leafy suburban town just off exit 51 of the Long Island Expressway (the acronym of the title), Cuesta’s film focuses on young Howie Blitzer (Dano), a troubled teen whose mother has recently been killed in a car accident on the notorious road.

His father (Altman) is a shady contractor with little time for his son, and so, with no emotional support, Howie begins ditching school and hooks up with an impoverished kid called Gary (Kay) who turns tricks on the expressway and burgles houses to fund his planned escape to California. There’s a close bond between the two kids and an erotic undercurrent that hints at Howie coming to terms with his own sexuality. But the chance for this relationship to develop is cut short when they’re caught breaking into the house of Big John Harrigan (Cox), a former Marine and well-respected member of the community.

Billy Kay as Gary (left) and Paul Dano as Howie in L.I.E.

It’s at this point that L.I.E. enters darker territory. Although the Vietnam veteran seems very well connected with the local cops and the staff at school, it transpires that he also enjoys the company of young boys. After Big John approaches them about the robbery, Howie discovers an alluring secret that binds his friend and the ex-Marine. Howie’s dad is then arrested for using unsafe building materials and so Howie is virtually abandoned, leaving the way for Big John to step in as paternal figure and predator.

The ambiguity of the Big John role was always going to cause controversy, but Cox – who delivers one of his finest performances – catches the troubling complexity of a man who simply can’t be written off as a stereotype. Cox plays him with a mixture of smooth-talking malevolent charm and genuine sympathy. So, while we are never allowed to forget he is a sinister, predatory figure, we also see a man battling his inner demons as he forges an unlikely friendship with the boy.

L.I.E. in no way excuses Big John’s past actions but it does suggest that life is more equivocal than most tabloid headline writers would have you believe.

This film could so easily have been a deliberately shocking, exploitative piece of cinema. Thankfully L.I.E. is a fantastic example of an American indie with subtle writing and direction, and a superb performance from Brian Cox. Of course, not surprisingly, in the end the suits and censors rated it as NC-17 in the US and opted for a 15 certificate in the UK. Yes, the film concerns teenage boys and an older man who preys on them sexually. But it’s handled responsibly, without nudity or lingering shots. In fact it could even provoke vital discussions between teens and parents. The NC-17 rating prevents that discussion.

Unfortunately, this hypocrisy is invariably at the expense of indie films, while studio pics like American Beauty, in which Kevin Spacey fantasises over the underage Mena Suvari, sneak through with just an R rating. Censors, ratings boards and the Hollywood system stink; Michael Cuesta’s film does not.

US, 95 mins

Director/Writer: John Cameron Mitchell

Cast: John Cameron Mitchell, Michael Pitt, Miriam Shore, Stephen Trask, Rob Campbell

Genre: Comedy musical

Hedwig and the Angry Inch, a Rocky Horror Picture Show for the 1990s, had director-star John Cameron Mitchell in the title role of Hedwig, the East German refugee and failed pop star.

Born a boy named Hansel whose life’s dream is to find his other half, Hedwig reluctantly submits to a sex-change operation in order to marry an American GI and get over the Berlin Wall to freedom.

The operation is botched, leaving her with the aforementioned ‘angry inch’. Finding herself high, dry and divorced in a Kansas trailer park, she pushes on to form a rock band and encounters a lover/protégé in young Tommy Gnosis (Michael Pitt), who eventually leaves her, steals her songs and becomes a huge rock star and totally rich and famous. What else can Hedwig do but stalk him from gig to gig?

Hedwig and the Angry Inch shadow Tommy’s massive stadium tour, performing in near-empty restaurants for bewildered diners and a few die-hard fans. But somewhere between the crab cakes and the crab motel rooms, between the anguish and the acid-wash, she pursues her dreams and discovers the origin of love.

The overall effect is of a journey: following this character through a traumatic but often exhilarating search for her identity. This may all sound like every other homosexual coming-of-age story, but Mitchell gives it a very universal feel, making sure to skirt the more embarrassing stereotypes that many gay-themed films often succumb to.

Mitchell retains the excitement of the theatre version by singing the musical numbers live on camera. You even get the audience sing-a-long section, complete with onscreen lyrics and a bouncing ball to keep everybody in time.

The action is interspersed with Emily Hubley’s quirky animations, particularly during the musical numbers. These are extremely effective during the ballad ‘The Origin Of Love’, in which Hedwig recounts a story from childhood about the creation of men and women.

This eccentric musical comedy-drama – based on the off-Broadway show of the same name – is packed with wigs, 1970s-style songs, lashings of eye shadow and bouffant hair, plus a generous helping of sharp one-liners. Audacious, funny and totally fabulous! Made for a paltry $6 million, it’s a brilliant triumph and a victory against big-budget, big-star pap.

US/France, 107 mins

Director/Writer: Todd Haynes

Cast: Julianne Moore, Dennis Quaid, Dennis Haysbert, Patricia Clarkson, Viola Davis

Genre: 1950s-set drama

Far From Heaven revisits the almost forgotten genre of the domestic melodrama. Drawing from the ‘womens’ films’ of the 1950s, particularly those of director Douglas Sirk, Todd Haynes’ reworking of Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows casts Julianne Moore as Connecticut housewife and mother Cathy Whitaker. She’s set up in a dream, portfolio house with a fine, upstanding husband, Frank (Quaid), and two kids.

Set in the fall of 1957, the melodrama begins when Cathy is returning home from a day of errands. Her husband is expected home for a dinner engagement. There’s only one problem – no one has heard from Frank all afternoon.

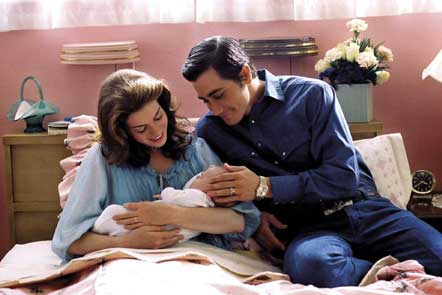

What begins as a curious snapshot of 1950s American values is soon transformed into a tangle of competing conflicts. Cathy discovers that her idyllic suburban life is a lie as she realises that her husband is having a gay affair. Trouble is, when Cathy finds solace in her formidable black gardener, Raymond (Haysbert), tongues start to wag, and she is faced with choices that spur hatred and gossip within the community.

Dennis Quaid and Julianne Moore in a scene from Far From Heaven

Frank goes to a doctor for ‘treatment’, and his confession is heartbreaking. He says that he ‘can’t let this thing, this sickness, destroy my life. I’m going to beat this thing’. We pity him because we realise that such a feat is impossible, and unnecessary, but Frank does not possess that knowledge.

Haynes spends a lot of time exploring the ideological tensions and contradictions concerning gender, sexuality and race that define the 1950s melodrama and highlights the confining concepts of sexuality alive in yesteryear and today. Its themes are relevant, valid and important, whether in the context of the 1950s or today. Haynes reminds us that homosexuality was seen as a disease; blacks were openly marginalised and humiliated; kids were often left to their own devices while busy parents ran cocktail parties; and white women with black men caused a public outcry. All this we already knew, and of course a lot of this still goes on, but because the film deliberately lacks irony, it still has a genuine dramatic impact. Indeed Haynes believes his film has a lot to say about today, not just life in the 1950s:

‘It’s a very sad story. Sadly, it’s a story that really could be told today in America. Basically it’s about these people, who look amazing, sound amazing, and move like none of us do, but who are ultimately very fragile people. They don’t tear down the walls of their society. They ultimately succumb to the pressures of their society, and in that way they’re more familiar than a lot of film subjects are – they’re really more like us.’