As Steven Paul Davies notes in the fascinating volume you have in your hands, we live in interesting times as far as the gay presence in cinema is concerned. For him, Brokeback Mountain is the great breakthrough into the mainstream, and though some of us may quarrel with his interpretation of the movie itself, there can be no doubting the enormity of the leap it represented. It stands in the long and by no means dishonourable homosexuality-as-problem tradition in the movies; indeed, it is arguably a film about the difficulties of bisexuality. But the fact that in a mainstream film two highly bankable and impeccably butch actors are shown making passionate love to each other, that no moral judgement is made on this, and that the actors’ careers were greatly advanced by appearing in it (one of them, of course, tragically curtailed) is a quite remarkable development; inconceivable to me 40 years ago when I started acting, much less so when I started going to films 15 years before that.

In those distant days, every homosexual was an expert decoder, as skilled as any to be found at Bletchley Park. Messages were being sent to us, and we learned to read the signs, to infer the hidden communications, to sniff out the double meaning. This was not without its thrills, but it’s no way for grown men and women to experience their lives. Little by little, things began to change. It had started already in the theatre, where illicit kisses had been exchanged, tortured psyches examined and what was now known as gay humour freely flaunted. The movies, as well documented by Davies, began to deal with the troublesome matter of same-sex attraction with increasing subtlety and truthfulness to life: it is hard to describe how powerful was the impact on the gay community of films such as Schlesinger’s great Sunday Bloody Sunday and Midnight Cowboy. Nonetheless, the prevailing mood was summed up by a line from Mart Crowley’s seminal – if I may so express myself – play then film, The Boys in the Band: ‘Show me a happy homosexual and I’ll show you a gay corpse.’ The notion of depicting the normal homosexual man or woman (as, by definition, most homosexual men and women are) was still thought of as dangerously radical. It must be said that perhaps homosexuals themselves contributed to this: the drama of being gay is central to many gay people’s identities. And indeed it took major social changes before gay lives could in any way be described as normal.

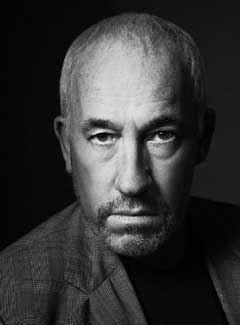

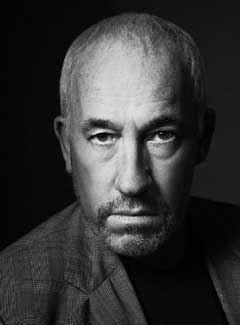

One of the great debates of the 1970s and 1980s was about the desirability of normalcy for gay people. Was homosexuality inherently radical? Was it of the essence of being gay that one was consciously distancing oneself from heterosexual norms? Were gay people born crusaders against conventional society, glorying in their otherness? Or was it our demand, indeed our right, to be accepted as part of society, just another strand of human existence, different in orientation but not in emotional experience, equal in the right freely to express our loves and desires, but not in any way superior? Militantly gay films are few, but many of the films described in this book fall naturally into one or other of two camps: those of a specifically gay sensibility, and those which attempt to depict gays as part of the general human situation. The specifically gay ones by no means necessarily advocate a separatist gay position, but they do insist on a viewpoint that sees the world differently, with homosexual eyes. The other kind of film seeks to integrate gays into the world at large. I appeared in what I suppose is one of the most important films of this kind, Four Weddings and a Funeral. Gareth, the character I played, was flamboyant but not camp; he belonged to no stereotypical category; and he died not of AIDS, which was at that time ravaging the gay community, but of Scottish dancing.

When I read the script, it was immediately evident that this was a new kind of gay character in films: not sensitive, not intuitive, kind and somehow Deeply Sad, nor hilarious, bitchy and outrageous, but masculine, exuberant, occasionally offensive, generous and passionate. He was also deeply involved with his partner, the handsome, shy, witty, understated Matthew. In the original screenplay, they were glimpsed at the beginning of the film asleep in bed. In the final cut, the filmmakers removed this sequence, in order to allow their relationship to creep up on the audience. They were right to do so: before they knew it, viewers had come to know and love them individually, and were hit very hard, first by Gareth’s death and then by Matthew’s oration (with a little help from another splendid bugger, WH Auden). Perhaps the most important moment in the film from a gay perspective was Hugh Grant’s remark after the eponymous funeral that while the group of friends whose amatory fortunes the film follows talked incessantly about marriage, they had never noticed that all along they had had in their midst an ideal marriage, that of Gareth and Matthew. It almost defies belief, but in the months after the release of the film, I received a number of letters from apparently intelligent, articulate members of the public saying that they had never realised, until seeing the film, that gay people had emotions like normal people. (I also had a letter from Sir Ian McKellen saying how much more important Four Weddings was in gay terms than the simultaneously released Philadelphia, with its welter of chaste histrionics.)

Gay men and women have now entered the mainstream of cinema, losing their exoticness on the way. They are, increasingly, just a part of life, though still generally a somewhat marginal part. Sexual roles are less fixed, not in a 1960s androgynous way, but in the sense that it might be possible to have sex or even an affair with someone of the same gender and not compromise one’s masculinity or femininity. Rose Troche’s Bedrooms and Hallways played most entertainingly with this idea: a gay man joins a men’s group, whose sexiest, most rampantly heterosexual member falls for him; the gay man himself later has a fling with the straight guy’s girlfriend. A highlight of this film about sexual musical chairs is the speech by the hunk (James Purefoy) hymning the unexpected delights of being anally penetrated. I played the co-ordinator of the group – straight. In fact, not a single gay character in the film was played by a gay actor. One of the ironic side effects of the new dispensation in movies was that straight actors were queuing up to play gay, and it became increasingly hard for gay actors to get the parts for which they were uniquely qualified. This issue, though scarcely a subject of deep concern, raises interesting questions about authenticity. It is striking that not a single gay person had anything to do with Brokeback Mountain, from the author of the original novella, to the director, to the actors. (Perhaps someone in make-up slipped through? Who can tell?) Would it have been different had gay artists been involved? Better? Or perhaps, to return to my earlier point, it isn’t really a film about being gay at all, simply about deep friendship which, under certain circumstances, turns sexual.

What, if anything, is missing from the gay cinematic scene? In fact, the single most significant piece of gay celluloid was a television series, Queer as Folk, which in telling it like it is (at least for the young and pretty), broke so many taboos that almost everything else was left looking pretty silly. Russell T Davies’s stunningly witty and truthful script was an account of what it is to be part of the scene today. But, of course, many – perhaps most – gay people aren’t part of that scene. There is a gay world elsewhere. Early in the 1970s, as part of a theatre company called Gay Sweatshop, I appeared in a little play by Martin Sherman called Passing By which I still regard as one of the most radical gay plays ever written. It showed two men meeting, falling in love with each other, falling out of love and then parting. At no point did they ever mention the word gay or homosexual, there was no reference to mothers or even Judy Garland. They simply found each other highly attractive and one thing led to another. It was amusing, touching, sexy and entirely normal. This little play has had few successors, on stage or screen. Jonathan Harvey’s Beautiful Thing, the film version of which Steven Paul Davies describes very well in these pages, was a sort of 1980s version of the same thing, though the youthfulness of the characters lent it a special poignancy; My Beautiful Launderette showed another sort of tender relationship which defied race and class in the most spontaneous, natural, innocent fashion. Ferzan Ozpetek’s exquisite Hammam, a film I think SPD is somewhat inclined to under-rate, showed the gradual, delicate development of feelings between a heterosexual Italian and a young Turk, a story which conveyed the gentle seduction of one culture by another. These are all quietly persuasive, lifelike accounts of the birth of homosexual desire.

What I personally would like to see is a story of overwhelming passion, a gay Antony and Cleopatra or Romeo and Juliet, on a grand scale. For that I suppose we need a gay Shakespeare. The gay directors who might have told that story – Zeffirelli, Visconti, Schlesinger – didn’t. Let’s hope that their successors will take the plunge. And let’s hope that two huge box-office stars who fully acknowledge their own gayness will play the leads. Meanwhile, Steven Paul Davies’s book describes the astonishing, moving, witty (and sometimes blissfully silly) things that have been achieved so far.