VAQUEROS OF THE SOUTHWEST

“Between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande … the brush country is still a cow country, and brush hands, mostly Mexicans, still ‘kill up’ their horses running wild cattle. … Here the mesquite is just one among many thorned growths, most of them known to the people of the region only by their Mexican names. They give the land a character as singular as that afforded to Corsica by the maquis or to Florida by the everglades. …

In running in this brush a vaquero rides not so much on the back of his horse as under and alongside. He just hangs on, dodging limbs as if he were dodging bullets, back, forward, over, under, half of the time trusting his horse to course right on this or that side of a bush or tree. If he shuts his eyes to dodge, he is lost. Whether he shuts tnem or no, he will, if he runs true to form, get his head rammed or raked. Patches of the brush hand’s bandana hanging on thorns and stobs sometimes mark his trail. The bandana of red is his emblem. … Unseen and unapplauded, he has never been pictured on canvas or in print. An ‘observer’ might hear him breaking limbs; that is all. When he does his most daring and dangerous work, he is out of sight down in a thicket.”

—J. FRANK DOBIE, A Vaquero of the Brush Country, Dallas, Texas, 1929.

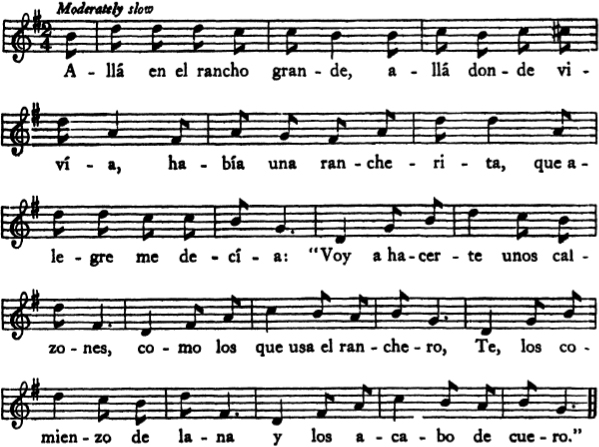

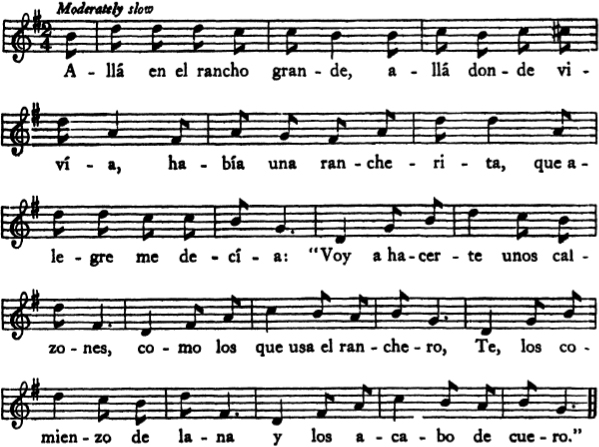

ALLÁ EN EL RANCHO GRANDE *

Composer and Author Silvano R. Ramos

Allá en el rancho grande, allá donde vivía,

Había una rancherita, que alegre me decía:

“Voy a hacerte unos calzones

Como los que usa el ranchero.

Te los comienzo de lana

Y los acabo de cuero.”

Down on the big ranch, down there where I lived,

There was a rancherita, who merrily said to me:

“I’m going to make you a pair of breeches

Like those that the ranchero wears.

I’ll begin making them of wool

And I’ll finish them in leather.”

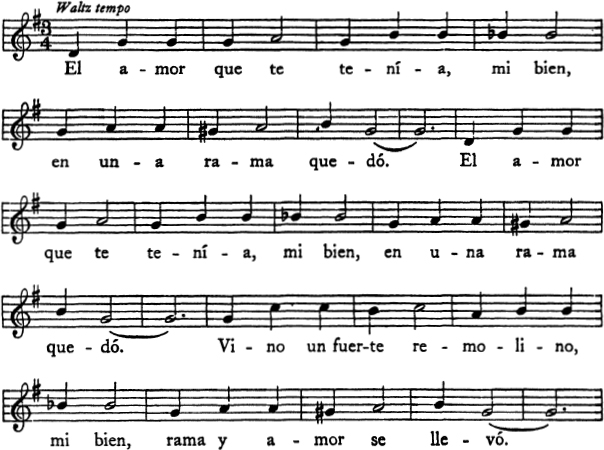

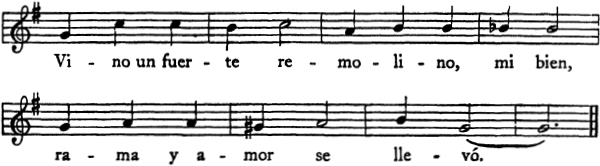

EL AMOR QUE TE TENÍA *

El amor que te tenía, mi bien,

En un ramo quedó.

El amor que te tenía, mi bien,

En un ramo quedó.

Vino un fuerte remolino, mi bien,

Rama y amor se llevó.

Vino un fuerte remolino, mi bien,

Rama y amor se llevó.

Mañana me voy pa’ San Diego, mi bien,

A sembrar frijol y arroz.

Mañana me voy pa’ San Diego, mi bien,

A sembrar frijol y arroz.

Y de allá te mando decir, mi bien,

Como se mancuernan dos.

Y de allá te mando decir, mi bien,

Como se mancuernan dos.

No me busques por vereda, mi bien,

Búscame de atravesía.

No me busques por vereda, mi bien,

Búscame de atravesía.

Y allá me hallaras cantando, mi bien,

Del amor que te tenía.

Y allá me hallaras cantando, mi bien,

Del amor que te tenía.

The love that I had for you, my dear,

Hanging from a branch remained.

The love that I had for you, my dear,

Hanging from a branch remained.

A strong whirlwind came along, my dear,

And branch and love took away.

A strong whirlwind came along, my dear,

And branch and love took away.

Tomorrow I’m going to San Diego, my dear,

To sow beans and rice.

Tomorrow I’m going to San Diego, my dear,

To sow beans and rice.

From there I’ll write to you, my dear,

About how to couple two.

From there I’ll write to you, my dear,

About how to couple two.

Do not look for me along the path, my dear,

Look for me along the short cut.

Do not look for me along the path, my dear,

Look for me along the short cut.

There you shall find me singing, my dear,

About the love I had for you.

There you shall find me singing, my dear,

About the love I had for you.

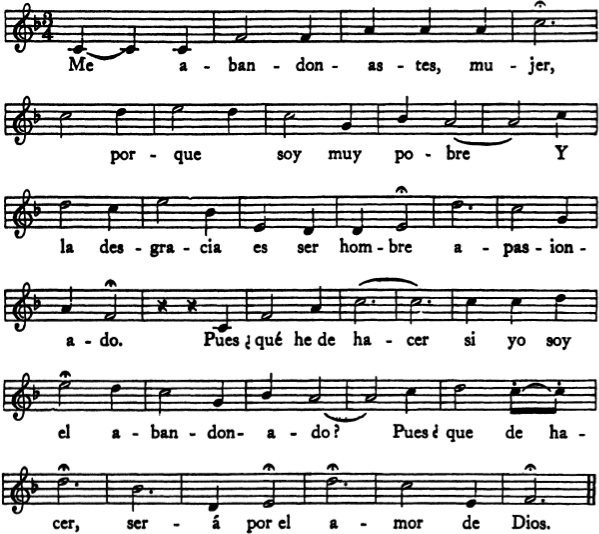

EL ABANDONADO (THE ABANDONED ONE)

“The love song is by far the most common of all Mexican folksongs. During the trail driving days many of the cowboys who drove herds from Southern Texas to Kansas and beyond were Mexicans. I have often asked old trail drivers if the vaqueros had any such songs as the Texas cowboys had. Invariably the answer has been that the vaqueros sang little else but love songs.” *

Me abandonastes, mujer, porque soy muy pobre

Y la desgracia es ser hombre apasionado.

Pues ¿qué he de hacer, si yo soy el abandonado?

Pues, qué he de hacer, será por el amor de Dios.

Tres vicios tengo, los tres tengo adoptados:

El ser borracho, jugador, y enamorado.

Pues ¿qué he de hacer, si soy el abandonado?

Pues, qué he de hacer, será por el amor de Dios.

Pero ando ingrato si con mi amor no quedo;

Tal vez otro hombre con su amor se habrá jugado.

Pues ¿qué he de hacer, si soy el abandonado?

Pues, qué he de hacer, será por el amor de Dios.

Translation

You abandon me, woman, because I am very poor; the misfortune is to be a man of passionate devotion. Then, what am I to do if I am the abandoned one? Well, whatever I am to do will be done by the will of God.

Three vices I have cultivated: gambling, drunkenness, and love. Then what am I to do if I am the abandoned one? Well, whatever I am to do will be done by the will of God.

But I go unhappy, if with my love I cannot remain. Perhaps another man has toyed with her love. Then what am I to do if I am the abandoned one? Well, whatever I am to do, will be done by the will of God.

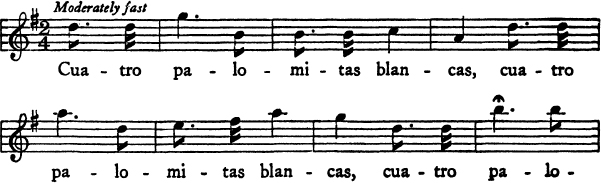

CUATRO PALOMITAS BLANCAS *

Cuatro palomitas blancas,

Cuatro palomitas blancas,

Sentadas en un alero,

Sentadas en un alero.

Unas a las otras dicen, (3)

“No hay amor como el primero.” (2)

Me gusta el pan con queso, (3)

Cuando se vive en el rancho. (2)

Pero mas me gusta un beso, (3)

Debajo de un sombrero ancho. (2)

Translation

Four little white doves,

Four little white doves,

Four little white doves,

Perched on a gable end,

Perched on a gable end.

They say to each other, (3)

“There is no love like the first.” (2)

When I live on a ranch. (2)

But I like a kiss much better, (3)

Under a broad-brimmed sombrero. (2)

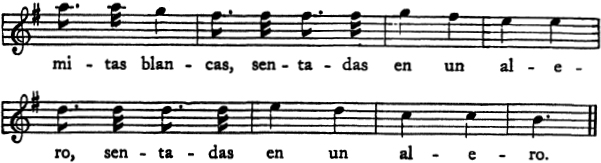

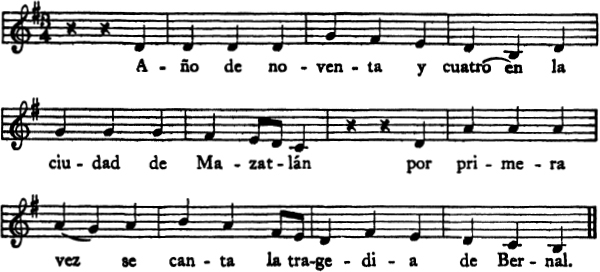

TRAGEDIA DE HERACLIO BERNAL

“The majority of the population of Mexico is today in the grip of a social system little, if materially at all, differing from that of the Middle Ages in Europe. … The peon wears shoes instead of sandals on feast-days, whereas his grandfather wore homemade brogans; but modernity has come no nearer home to him than this. His culture, aspirations, and life, those of the days of Robin Hood and the Cid … have served to produce there the ‘tragedia,’ a form of ballad which is purely medieval in atmosphere and inspiration. … The ‘tragedia’ is a product of the people themselves. It is rarely ever printed or even reduced to writing. Its verses are composed orally and are preserved in the memory of the … strolling guitar or harp players who are the counterpart of the medieval ‘juglar.’ … One of the most popular, and also one of the most typical of the bandit ballads is the extremely fragmentary one that follows. It celebrates the deeds of one Heraclio Bernal, a bandit who was active in Northwestern Mexico during the eighties and early nineties, and who was the cause of considerable embarrassment to the Mexican government before he was finally killed near Mazatlán. Every singer in Northwestern Mexico knows fragments of this ballad, though no one seems to possess it entire. … Bernal, in the mouth of the improviser of the ballads, takes on all the attributes of the popular hero of the Robin Hood type, robbing the rich to give to the poor, and defying tyrannical authority in a truly medieval fashion.” *

Translation |

|

Año de noventa y cuatro |

In the year of ninety-four, in the city of Mazatlán, this, the song of Bernal, is sung for the first time. |

Heraclio Bernal decía |

Heraclio Bernal, when he visited Saucillos, was wont to declare that he carried silver in his pocket and cartridges at his waist. |

| Refrain: | |

Vuela, vuela, palomita, |

Fly, little dove, and perch upon yonder cactus; and proclaim that ten thousand pesos are offered for the head of Bernal. |

Una familia en la sierra |

A family in the mountains was in dire poverty; and he gave them five hundred pesos to mend their fortunes. |

Heraclio Bernal decía |

Heraclio Bernal would say, when he met a muleteer, that he did not rob the poor, but rather gave them money. |

En la sierra de Durango |

In the mountains of Durango he killed ten Spaniards, and had their skins tanned to make boots withal. |

Decía doña Bernardina |

Doña Bernardina, the mistress of Bernal, said: “I will have a portrait made of him, though it cost me my life.” |

Y lo retrató entonces |

And she had his portrait painted, riding upon his bay horse, and smoking a cigar in the midst of a troop of mounted police. |

Desde Torreón de Coahuila |

From Torreón in Coahuila to the waters of the sea, he wandered at will, and none dared to molest him. |

En una vez en la sierra |

On a time in the mountains, they took him by surprise; he and Fabián the Indian were besieged in a narrow valley. |

Y Heraclio Bernal decía, |

And Heraclio Bernal, mounted on his sorrel horse, said to him: “Now we will break the siege and enter Mazatlán.” |

Y de siete de los Rochas |

And of the seven Rochas who came to apprehend them, safe and well to their homes only three returned. |

Decía don Crispín García, |

Said Don Crispín García, the mayor of Mazatlán: “Let me have two troops of mounted police and the National Guard.” |

Y en Mazatlán lo mataron, |

And in Mazatlán he was killed, by treason and from behind, for that Don Crispín García was skillful in treason. |

Todavía despues de muerto |

And even after he was dead, as he lay in his coffin, the mounted police and the soldiers feared him greatly. |

| ...................... | |

¡ Ay, ricos de la costa! |

O rich men of the coast! No longer will you die of fear; now they have killed Bernal, now you may sleep at your ease. |

Y lloran todas las muchachas |

And all of the girls of the mines of Mapimí weep and say: “Now they have killed Bernal, never will he return.” |

Y aquí termino mi canto |

And here I end my song, for thus ended the deeds and the life of the great Heraclio Bernal. |

Copyright 1927, by Edward B. Marks Music Corporation.

* Publications of the Texas Folk-Lore Society.

* Publications of the Texas Folk-Lore Society.

* Frank Dobie, in “Verses of the Texas Vaqueros” (Publications of the Texas Folk-Lore Society).

* Publications of the Texas Folk-Lore Society.

* W. A. Whatley in the Publications of the Texas Folk-Lore Society.

* The acordada is a troop of Mexican mounted rural police.