SAILORS AND SEA FIGHTS

“She’s a deep-water ship an’ a deep-water crew.

Ye can keep to the coast, but we’re damned if we do.”

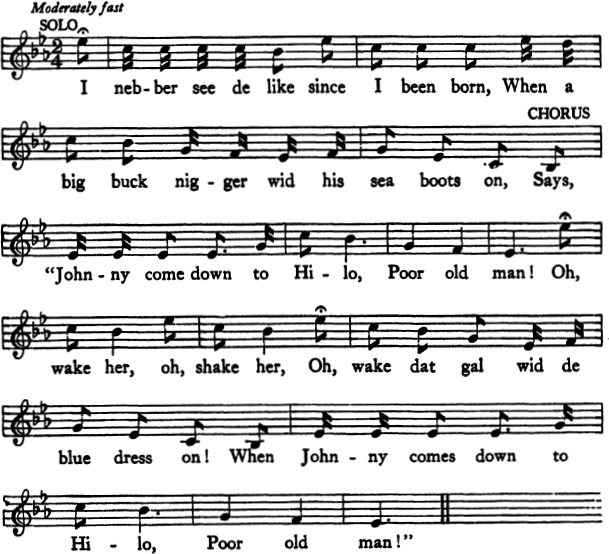

JOHNNY COME DOWN TO HILO*

“Shanties which were originated by the Negro stevedores in the Gulf ports form a large class. … These songs were developed as an aid in stowing cotton, the bales being rammed tightly into the ship’s hold. … As the shanties proved useful, either for hauling or for the windlass, they were picked up by the ships’ crews and became part of the shantyman’s repertoire. …

“There can be no doubt of the Negro origin of the next shanty; as to how, when or where, there is no trace. The lines are a mixture taken from other shanties; scarcely one is peculiar to this shanty alone, although the melody is distinctive enough. Bullen says that it ‘brings to my mind most vividly a dewy morning in Garden Reach where we lay just off the King of Oudh’s palace waiting our permit to moor. I was before the mast in one of Berat’s ships, the Herat, and when the order came at dawn to man the windlass I raised this shanty and my shipmates sang the chorus as I never heard it sung before or since. There was a big ship called the Martin Scott lying inshore of us and her crew were all gathered on deck at their coffee when the order came to ‘Vast Heaving,’ the cable was short. And that listening crew, as soon as we ceased singing, gave us a stentorian cheer, an unprecedented honor. I have never heard that noble shanty sung since, but sometimes even now I can in fancy hear its mellow notes reverberating amid the fantastic buildings of the palace and see the great flocks of pigeons rising and falling as the strange sounds disturbed them.”

I neber see de like since I been born,

When a big buck nigger wid his sea boots on,

CHORUS

Says: “Johnny come down to Hilo,

Poor old man!

Oh, wake her, oh, shake her,

Oh, wake dat gal wid de blue dress on!

When Johnny comes down to Hilo,

Poor old man!”

I lub a little gal across de sea;

She’s a ’Badian beauty, and she says to me:

“Oh, was you ebber down in Mobile Bay,

Where dey screws cotton on a summer day?

“Did you ebber see de old plantation boss,

And de long-tail filly and de big black hoss?”

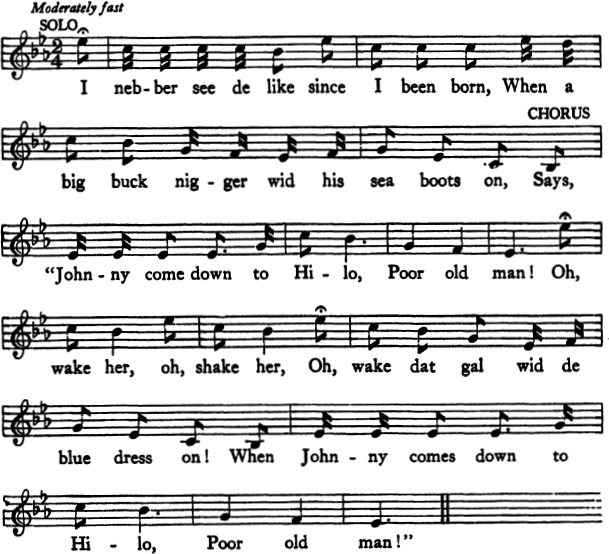

HEAVE AWAY*

I’d rather court a yellow gal than work for Henry Clay.

Heave away, heave away!

Yellow gal, I want to go,

I’d rather court a yellow gal than work for Henry Clay.

Heave away!

Yellow gal, I want to go!

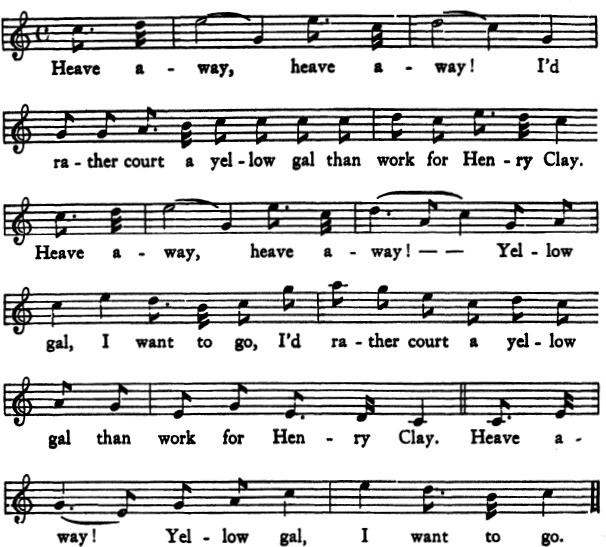

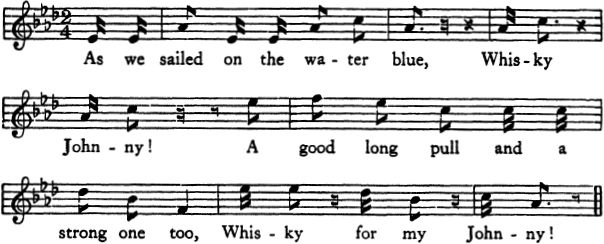

WHISKY JOHNNY*

As we sailed on the water blue,

Whisky Johnny!

A good long pull and a strong one too,

Whisky for my Johnny!

Whisky killed my brother Tom,

Whisky Johnny!

I drink whisky all day long,

Whisky for my Johnny!

Whisky made me pawn my clothes,

Whisky Johnny!

Whisky for my Johnny!

Whisky is the life of man,

Whisky Johnny!

I’ll drink my whisky while I can,

Whisky for my Johnny!

Oh, whisky straight and whisky strong,

Whisky Johnny!

Give me whisky and I’ll sing you a song,

Whisky for my Johnny!

Whisky killed my poor old dad,

Whisky Johnny!

Whisky druv my mother mad,

Whisky for my Johnny!

I drink whisky, my wife drinks gin,

Whisky Johnny!

And the way she drinks it is a sin,

Whisky for my Johnny!

I and my wife cannot agree,

Whisky Johnny!

For she drinks whisky in her tea,

Whisky for my Johnny!

I had a girl, her name was Lize,

Whisky Johnny!

She puts whisky in her pies,

Whisky for my Johnny!

Whisky stole my brains away,

Whisky Johnny!

The bos’n pipes and I’ll belay,

Whisky for my Johnny!

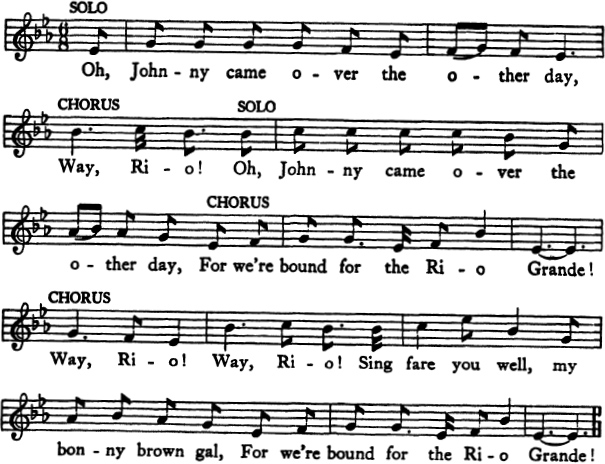

THE RIO GRANDE*

Oh, Johnny came over the other day,

Way, Rio!

Oh, Johnny came over the other day,

For we’re bound for the Rio Grande!

Chorus:

Way, Rio!

Way, Rio!

Sing fare you well, my bonny brown gal,

For we’re bound for the Rio Grande!

“Now give me your hand, my dear lily-white;

Way, Rio!

If you’ll accept me, I’ll make you my wife.”

For we’re bound for the Rio Grande!

“Now, Johnny, I love you and don’t want you to go,

Way, Rio!

And if you stay I’ll love you so so.”

For we’re bound for the Rio Grande!

Additional couplets

She’s a deep-water ship, an’ a deep-water crew.

Ye can keep to the coast, but we’re damned if we do.

We was sick of the beach when our money was gone,

And signed in this packet to drive her along.

Oh, blow ye winds steadily; fair may ye blow.

She’s a starvation packet, good God, let ’er go!

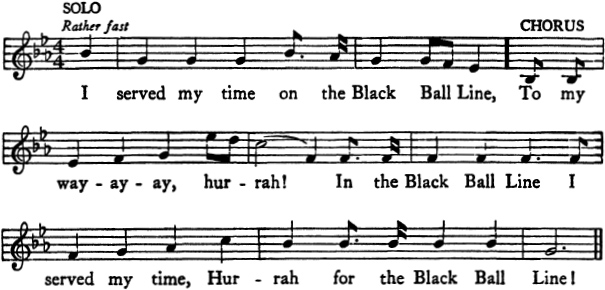

THE BLACK BALL LINE*

“… celebrates the first and most famous line of American packet ships to run between New York and Liverpool. Started in 1816, these little ships of 300 to 500 tons furnished for many years the only means of regular communication between this continent and Europe, sailing regularly from New York on the first and sixteenth of each month. In order to keep up their average time of three weeks out and six weeks home, the ships were driven unmercifully, and acquired a bad name among sailors for the iron discipline maintained on board. The Black Ball liners carried a crimson swallowtail flag with a black ball in the center.…”

I served my time on the Black Ball Line,

CHORUS

To my way-ay-ay, hurrah!

SHANTY-MAN

In the Black Ball Line I served my time,

CHORUS

Hurrah for the Black Ball Line!

Once there was a Black Ball ship

That fourteen knots an hour could clip.

You will surely find a rich gold mine;

Just take a trip in the Black Ball Line.

Just take a trip to Liverpool,

To Liverpool, that Yankee school.

The Yankee sailors you’ll see there,

With red-top boots and short-cut hair.

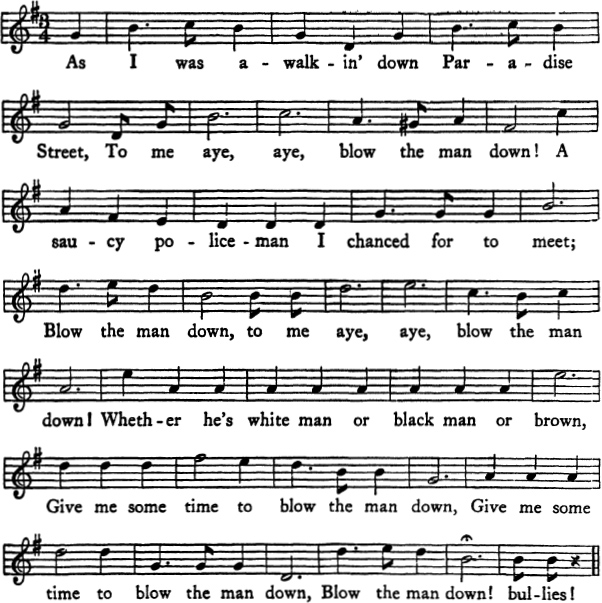

BLOW THE MAN DOWN*

As I was a-walkin’ down Paradise Street,

To me aye, aye—blow the man down!

A saucy young p’liceman I chanced for to meet;

Blow the man down, to me aye, aye, blow the man down!

Whether he’s white man or black man or brown,

Give me some time to blow the man down,

Give me some time to blow the man down,

Blow the man down! bullies!

“You’re off some clipper that flies the Black Ball,”

To me aye, aye—blow the man down!

“You’ve robbed some poor Dutchman of coats, boots, and all.”

Blow the man down, etc.

“P’liceman, p’liceman, you do me much wrong,”

To me aye, aye—blow the man down!

“I’m a peace party sailor just home from Hongkong.”

Blow the man down, etc.

They gave me six months in the Ledington jail,

To me aye, aye—blow the man down!

For kickin’ an’ fightin’ and knockin’ ’em down;

Blow the man down, etc.

Other versions of “Blow the Man Down,” the first quoted from the collection of William Doerflinger:

As I was walkin’ down Paradise Street,

To my aye, aye—blow the man down!

A handsome young damsel I chanced for to meet,

Blow the man down, etc.

I came alongside her and took her in tow,

To my aye, aye—blow the man down!

And broadside to broadside away we did go,

Blow the man down, etc.

***

Bryan O’Lynn had no breeches to wear,

To my aye, aye—blow the man down!

So we bought a sheepskin and made him a pair,

Blow the man down, etc.

With the skinny side out and the woolly side in,

To my aye, aye—blow the man down!

A fine pair of breeches had Bryan O’Lynn,

Blow the man down, etc.

GET UP, JACK! JOHN, SIT DOWN!*

Oh, the ships will come and the ships will go,

As long as the waves do roll:

The sailor lad, likewise his dad,

He loves the flowing bowl:

A lass ashore we do adore,

One that is plump and round, round, round.

When the money is gone, it’s the same old song,

Get up, Jack! John, sit down!

Chorus:

Singing, Hey! laddie, ho! laddie,

Swing the capstan ’round, ’round, ’round

When the money is gone it’s the same old song,

Get up, Jack! John, sit down!

[I] go and take a trip in a man-o’-war

To China or Japan,

In Asia, there are ladies fair

Who love the sailorman.

When Jack and Joe palavers, O,

And buy the girls a gown, gown, gown.

When the money is gone it’s the same old song,

Get up, Jack! John, sit down!

When Jack is ashore he beats his way

Towards some boarding-house:

He’s welcome in with his rum and gin,

And he’s fed with pork and s[c]ouse:

For he’ll spend and spend and never offend,

But he’ll lay drunk on the ground, ground, ground:

When my money is gone it’s the same old song:

Get up, Jack! John, sit down!

When Jack is old and weatherbeat,

Too old to roustabout,

In some rum-shop they’ll let him stop,

At eight bells he’s turned out.

Then he cries, he cries up to the skies:

“I’ll soon be homeward bound, bound, bound.”

When my money is gone it’s the same old song:

Get up, Jack! John, sit down!

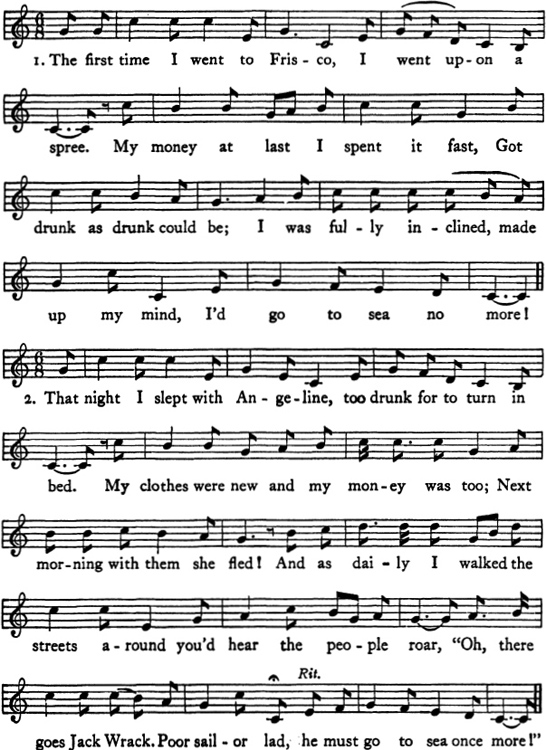

JACK WRACK*

“Frank Vickery, mate of the four-masted cargo schooner Avon Queen, whose home port is on the Mirimichi River in New Brunswick, began during a lonely anchor watch one night to relate some of his experiences with well-known boarding-house masters during the great days of sail. These memories brought to his mind the rare forecastle ballad of ‘Jack Wrack’—how Jack lost his money on the famous Barbary Coast in Frisco, and was shipped off to sea again in a whaler bound to the Bering grounds, for a long voyage which may have lasted two or three years.

“‘Shanghai’ Brown is among that coterie of more notorious boarding-house masters who were known to nearly every sailorman. His place stood on Battery Street in San Francisco in the days when shipmasters must pay head money for their crews and when men before the mast were the prey of land sharks who took their money and their advances and then hustled them into the forecastles of outward-bounders. I have heard the song under the title ‘Ben Breezer,’ also, while the lines of a variant called ‘Dixie Brown’ are to be found in Mackenzie’s Ballads and Sea Songs from Nova Scotia.”

The first time I went to Frisco, I went upon a spree.

My money at last I spent it fast, got drunk as drunk could be;

I was fully inclined, made up my mind, to go to sea no more!

That night I slept with Angeline, too drunk for to turn in bed.

My clothes was new, and my money was too;

Next morning with them she fled!

And as daily I walked the streets around you’d hear the people roar,

“Oh, there goes Jack Wrack! Poor sailor lad, he must go to sea once more!”

The first one that I came to was a son-of-a-gun called Brown.

I asked him for to take me in; he looked on me with a frown.

He says, “Last time you were paid off, with me you chalked no score,

But I’ll take your advance and I’ll give you a chance to go to sea once more!”

He shipped me on board of a whaler, bound for the Arctic seas.

The wintry wind from the west-nor’west Jamaica rum would freeze!

With a twenty-foot oar in each man’s hand we pulled the livelong day;

It was then I swore when once on shore I’d go to sea no more!

Come all you young seafaring men that’s listening to my song!

I hope in what I’ve said to you that there is nothing wrong.

Take my advice and don’t drink strong drinks, or go sleeping on the shore,

But get married, my boys, and have all night in, and go to sea no more!

THE BOSTON COME-ALL-YE*

OR

THE FISHES

“We have the testimony of Kipling in Captains Courageous that it was a favorite within recent years of the Banks fishermen.”

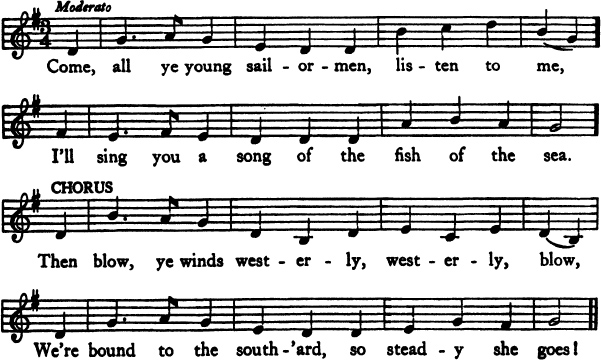

Come, all ye young sailormen, listen to me,

I’ll sing you a song of the fish of the sea.

Chorus:

Then blow ye winds westerly, westerly blow,

We’re bound to the south’ard, so steady she goes!

Oh, first come the whale, the biggest of all;

He clumb up aloft and let every sail fall.

And next come the mack’rel with his striped back;

He hauled aft the sheets and boarded each tack.

Then come the porpoise with his short snout;

He went to the wheel, calling “Ready! About!”

Then come the smelt, the smallest of all;

He jumped to the poop and sung out “Topsail, haul!”

The herring come saying, “I’m the king of the seas,

If you want any wind, why, I’ll blow you a breeze.”

Next come the cod with his chucklehead;

He went to the main-chains to heave at the lead.

Next come the flounder as flat as the ground;

Says, “Damn your eyes, chucklehead, mind how you sound!”

THE WONDERFUL CROCODILE

H. E. Greenough writes from Dartmouth, Nova Scotia (January 26, 1921):

“I have known this song since a boy … one of those that used to be roared out in the back rooms of the taverns frequented by seamen forty or so years ago.”

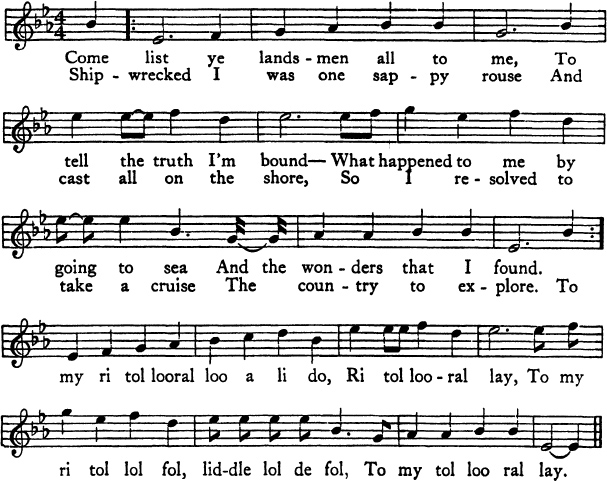

Come list ye, landsmen, all to me,

To tell the truth I’m bound—

What happened to me by going to sea

And the wonders that I found.

Shipwrecked I was one sappy rouse

And cast all on the shore,

So I resolved to take a cruise,

The country to explore.

Chorus:

To my ri tol looral loralido,

Ritol looral lay,

To my ri tol lol fol liddle lol de fol,

To my tol looral lay.

Oh, I had not long scurried out,

When close alongside the ocean,

’Twas there that I saw something move,

Like all the earth in motion.

While steering close up alongside

I saw it was a crocodile;

From the end of his nose to the tip of his tail

It measured five hundred mile.

This crocodile I could plainly see

Was none of the common race,

For I had to climb a very high tree

Before I could see his face.

And when he lifted up his jaw,

Perhaps you may think it a lie,

But his back was three miles through the clouds

And his nose near touched the sky.

Oh, up aloft the wind was high,

It blew a hard gale from the south;

I lost my hold and away I flew

Right into the crocodile’s mouth.

He quickly closed his jaws on me,

He thought to nab a victim;

But I slipped down his throat, d’ye see,

And that’s the way I tricked ’im.

I traveled on for a year or two

Till I got into his maw,

And there were rum kegs not a few

And a thousand bullocks in store.

Through life I banished all my care

For on grub I was not stinted;

And in this crocodile lived ten years,

Very well contented.

This crocodile being very old,

One day at last he died;

He was three years in catching cold,

He was so long and wide.

His skin was three miles thick, I’m sure,

Or very near about;

For I was full six months or more

In making a hole to get out.

So now I’m safe on earth once more,

Resolved no more to roam.

In a ship that passed I got a berth,

So now I’m safe at home.

But, if my story you should doubt,

Did you ever cross the Nile—

’Twas there he fell—you’ll find the shell

Of this wonderful crocodile.

You captains bold and brave, hear our cries, hear our cries,

You captains bold and brave, hear our cries,

You captains brave and bold, though you seem uncontrolled,

Don’t for the sake of gold lose your souls, lose your souls.

Don’t for the sake of gold lose your souls.

My name was Robert Kidd, when I sailed, when I sailed.

My name was Robert Kidd, when I sailed,

My name was Robert Kidd, God’s laws I did forbid,

And so wickedly I did, when I sailed.

My parents taught me well, when I sailed, when I sailed,

My parents taught me well, when I sailed,

My parents taught me well to shun the gates of hell,

But against them I rebelled when I sailed.

I cursed my father dear when I sailed, when I sailed,

I cursed my father dear when I sailed,

I cursed my father dear and her that did me bear,

And so wickedly did swear when I sailed.

I made a solemn vow when I sailed, when I sailed,

I made a solemn vow when I sailed,

I made a solemn vow to God I would not bow,

Nor myself one prayer allow, as I sailed.

I’d a Bible in my hand when I sailed, when I sailed,

I’d a Bible in my hand when I sailed,

I’d a Bible in my hand by my father’s great command,

And sunk it in the sand when I sailed.

I murdered William Moore, as I sailed, as I sailed,

I murdered William Moore, as I sailed,

I murdered William Moore, and left him in his gore,

Not many leagues from shore, as I sailed.

And being cruel still, as I sailed, as I sailed,

And being cruel still, as I sailed,

And being cruel still, my gunner I did kill,

And his precious blood did spill, as I sailed.

My mate was sick and died, as I sailed, as I sailed,

My mate was sick and died as I sailed,

My mate was sick and died, which me much terrified,

When he called me to his bedside, as I sailed,

And unto me did say, “See me die, see me die,”

And unto me did say, “See me die,”

And unto me did say, “Take warning now by me,

There comes a reckoning day, you must die.

“You cannot then withstand, when you die, when you die,

You cannot then withstand when you die,

You cannot then withstand the judgment of God’s hand,

But bound then in iron bands you must die.”

I was sick and nigh to death, as I sailed, as I sailed,

I was sick and nigh to death, as I sailed,

I was sick and nigh to death, and I vowed at every breath,

To walk in wisdom’s ways as I sailed.

I thought I was undone, as I sailed, as I sailed,

I thought I was undone as I sailed,

I thought I was undone and my wicked glass had run,

But health did soon return, as I sailed.

My repentance lasted not, as I sailed, as I sailed,

My repentance lasted not, as I sailed,

My repentance lasted not, my vows I soon forgot,

Damnation’s my just lot, as I sailed.

I steered from sound to sound, as I sailed, as I sailed,

I steered from sound to sound, as I sailed,

I steered from sound to sound, and many ships I found,

And most of them I burned, as I sailed.

I spied three ships from France as I sailed, as I sailed,

I spied three ships from France, as I sailed,

I spied three ships from France, to them I did advance,

I took them all by chance, as I sailed.

I spied three ships of Spain as I sailed, as I sailed,

I spied three ships of Spain, as I sailed,

I spied three ships of Spain, I fixed on them amain,

Till most of them were slain, as I sailed.

I’d ninety bars of gold as I sailed, as I sailed,

I’d ninety bars of gold as I sailed,

I’d ninety bars of gold and dollars manifold,

With riches uncontrolled, as I sailed.

Then fourteen ships I saw, as I sailed, as I sailed,

Then fourteen ships I saw, as I sailed,

Then fourteen ships I saw, and brave men they were,

Ah! they were too much for me, as I sailed.

Thus being o’ertaken at last, I must die, I must die,

Thus being o’ertaken at last, I must die,

Thus being o’ertaken at last, and into prison cast,

And sentence being passed, I must die.

Farewell, the raging sea, I must die, I must die,

Farewell, the raging sea, I must die,

Farewell, the raging main, to Turkey, France, and Spain,

I ne’er shall see you again, I must die.

To Newgate now I’m cast, and must die, and must die,

To Newgate now I’m cast, and must die,

To Newgate now I’m cast, with a sad and heavy heart,

To receive my just desert, I must die.

To Execution Dock I must go, must go,

To Execution Dock I must go,

To Execution Dock will many thousands flock,

But I must bear the shock, I must die.

Come all you young and old, see me die, see me die,

Come all you young and old, see me die,

Come all you young and old, you’re welcome to my gold,

For by it I’ve lost my soul, and must die.

Take warning now by me, for I must die, for I must die,

Take warning now by me, for I must die,

Take warning now by me, and shun bad company,

Lest you come to hell with me, for I must die,

Lest you come to hell with me, for I must die.

THE FLYING CLOUD*

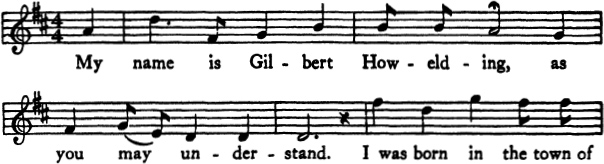

My name is Gilbert Howelding, as you may understand.

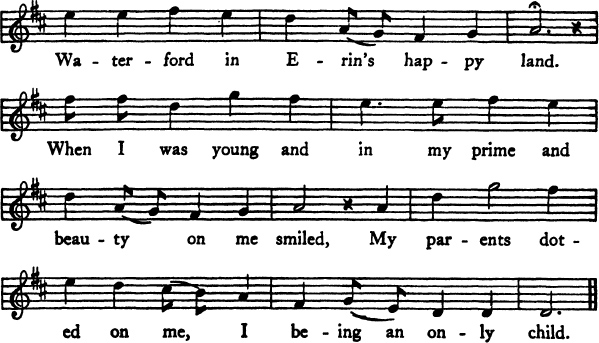

I was born in the town of Waterford in Erin’s happy land.

When I was young and in my prime and beauty on me smiled,

My parents doted on me, I being an only child.

My parents bound me to a trade near Waterford’s own town,

They bound me to a cooper there whose name was William Brown.

I served him true and faithful for eighteen months or more,

When I shipped on board the Ocean Queen bound for Belfrasia’s shore.

When I reached Belfrasia I fell in with Captain Moore,

Commander of the Flying Cloud, belonging to Try More.

He asked me if I would consent on a sailing voyage to go

To the burning shores of Africa where the sugar cane does grow.

The Flying Cloud was a Spanish ship, five hundred tons she bore,

She could easily sail around any ship going out of Baltimore,

Her sails they were as white as snow, on them there was no stain,

And eight nine-pounder big brass guns she carried abaft her main.

So in a short while after we reached the African shore,

And eighteen hundred of those poor men from their native home we bore,

We crowded them upon the deck and stored them all below

With eighteen inches to the man, was all they had to go.

We set sail shortly after with our cargo of slaves.

’Twas better then for those poor souls if they had seen their graves—

The plague and fever came on board and swept them half away;

We dragged their bodies on the deck and throwed them on the waves.

’Twas in a short time after we reached the Cuban shore,

And sold them to the planters there to be slaves for evermore,

Where the tea and coffee fields do grow beneath the burning sun,

To lead a long and wretched life till their long career is done.

Well, when our money was spent we struck out for sea again,

And Captain Moore he came on board and said to us, his men,

“There’s gold and silver to be had if with me you’ll remain,

We’ll hoist the Haughty Pirate’s flag and scour the Spanish Main.”

At last we all consented, excepting five young men,

Two of them were Boston boys, two more from Newfoundland,

The other was an Irish lad belonging to Try More—

I wish to God I’d joined those men and staid with them on shore.

We robbed and plundered many a ship along the Spanish Main,

Left many a widow and orphan in sorrow to remain.

Their crews, we made them walk the plank, gave them a watery grave,

For the saying of our captain was that dead men tell no tales.

We were chased it was full many a time by lines and frigates too.

Full many a time across our bows their burning shells they threw,

Full many a time astern of us their cannon roared loud,

But ’twas vain for them who’d ever try to catch the Flying Cloud.

A man-of-war, an English ship, from the navy hove in view

And fired a shot across our bow for a signal to heave to.

We paid no heed to answer back but made haste with the wind,

When a chance shot struck our mainmast, and we were forced to heave to then.

We cleared our deck for action as she came up alongside,

And soon across our quarter deck there ran the crimson tide,

We fought till Captain Moore was killed with eighteen of our men.

When a bombshell set our ship on fire, we were forced to surrender then.

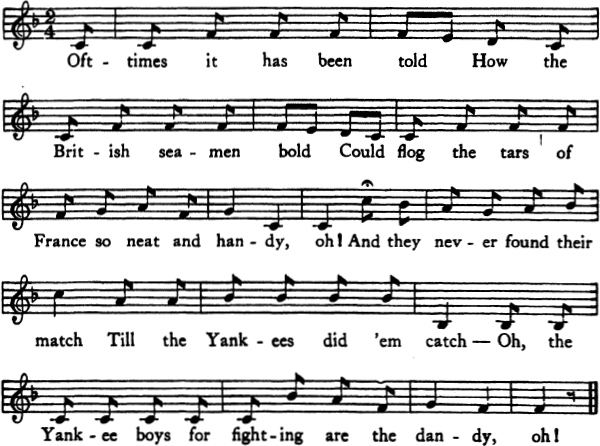

CONSTITUTION AND GUERRIÈRE*

How the British seamen bold

Could flog the tars of France

So neat and handy, oh!

And they never found their match

Till the Yankees did ’em catch—

Oh, the Yankee boys, for fighting

Are the dandy, oh!

The Guerrière, a frigate bold,

On the foamy ocean rolled,

Commanded by proud Dacres—

The grandee, oh!

With as choice a British crew

As a rammer ever drew—

They could flog the Frenchmen

Two to one, so handy, oh!

When the Constitution hove in view,

Says proud Dacres to his crew,

“Come, clear the ship for action,

And be handy, oh!

“To the weather gage now get her,

And to make our men fight better,

Give them to drink gunpowder,

Mixed with brandy, oh!”

Now, the British shot flew hot,

Which the Yankees answered not,

Till they got within the distance

They called handy, oh!

Then the first broadside we poured

Carried their mainmast by the board—

Which made their lofty frigate

Look abandoned, oh!

Our second told so well

That their fore and mizzen fell,

Which downed the royal ensign

So handy, oh!

Then proud Dacres came on board

To deliver up his sword—

Loath was he to part with it,

’Twas so handy, oh!

“Oh, keep your sword,” says Hull,

“If it only makes you dull,—

Come! cheer up, and let us have

A little brandy, oh!”

Then fill your glasses full

And we’ll drink to Captain Hull,

And merrily we’ll push about

The brandy, oh!

John Bull may toast his fill,

Let the world say what it will,

But the Yankee boys for fighting

Are the dandy, oh!

SIEGE OF PLATTSBURG *

Back side Albany stan’ Lake Champlain—

Little pond, half full of water.

Platt’burg dere too, close upon de main,

Town small—he grow bigger, do, hereafter.

Uncle Sam set he boat,

And Massa M’Donough to sail ’em,

While General Macomb

Make Platt’burg he home

Wid de army, who courage neber fail ’em.

On ’lebenteenth day of Sep-tem-ber

In eighteen hund’ed and fourteen,

Gubbener Probose, and he British sojer,

Come to Plat-te-burg, a tea-party courtin’;

And he boat come too

Arter Uncle Sam boat.

Massa Donough do look sharp out de winder.

Den General Macomb

(Ah, he always a-home)

Catch fire, too, jis’ like a tinder.

Bang! bang! bang! den de cannons ’gin to roar

In Platt’burg and all ’bout dat quarter.

Gubbener Probose try he hand upon de shore,

While he boat take he luck ’pon de water,

But Massa M’Donough

Knock de boat in de head,

Break he heart, broke he shin, ’tove he caff in,

And Gen’ral Macomb

Start old Probose home.

Tot me soul, den, I mos’ die a-laffin’.

Probose scare so, he lef’ all behin’—

Powder, ball, cannon, teapot, an’ kittle.

Some say he catch a col’, trouble in he min’

’Cause he eat so much col’ and raw victual’.

Uncle Sam berry sorry

To be sure for he pain,

Wish he nuss heself up well and hearty

For Gen’ral Macomb

And Massa Donough home,

When he notion for anudder tea-party.

THE BUCCANEERS*

“THE DEAD MAN’S CHEST”

Fifteen men on the Dead Man’s Chest,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

Drink and the devil had done for the rest,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

The mate was fixed by the bo’sun’s pike,

An’ the bo’sun brained by a marlinspike,

And the cookie’s throat was marked belike;

It had been clutched by fingers ten,

And there they lay, all good, dead men,

Like break o’ day in a boozin’ ken—

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

Fifteen men of a whole ship’s list,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

Dead and bedamned and their souls gone whist,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

The skipper lay with his nob in gore

Where the scullion’s ax his cheek had shore,

And the scullion he was stabbed times four;

And there they lay, and the soggy skies

Dripped ceaselessly in upstaring eyes,

By murk sunset and by foul sunrise—

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

Fifteen men of ’em stiff and stark,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

Ten of the crew bore the murder mark,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

’Twas a cutlass swipe or an ounce of lead,

Or a gaping hole in a battered head,

And the scuppers’ glut of a rotting red;

And there they lay, ay, damn my eyes,

Their lookouts clapped on Paradise,

Their souls gone just the contrawise—

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

Fifteen men of ’em good and true,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

Every man Jack could ’a’ sailed with Old Pew,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

There was chest on chest of Spanish gold

And a ton of plate in the middle hold,

And the cabin’s riot of loot untold—

And there they lay that had took the plum,

With sightless eyes and with lips struck dumb,

And we shared all by rule o’ thumb—

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

More was seen through the stern light’s screen,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

Chartings undoubt where a woman had been,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

A flimsy shift on a bunker cot

With a dirk slit sheer through the bosom spot

And the lace stiff dry in a purplish rot—

Or was she wench or shuddering maid,

She dared the knife and she took the blade—

Faith, there was stuff for a plucky jade!

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

Fifteen men on the Dead Man’s Chest,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

Drink and the devil had done for the rest,

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

We wrapped ’em all in a mainsail tight

With twice ten turns of a hawser’s bight,

And we heaved ’em over and out of sight,

With a yo-heave-ho and a fare-ye-well,

And a sullen plunge in a sullen swell,

Ten fathoms along on the road to hell—

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum!

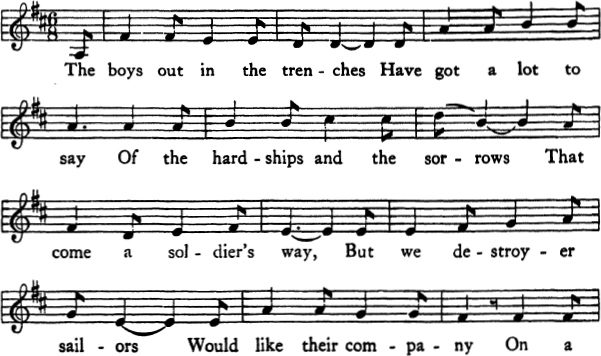

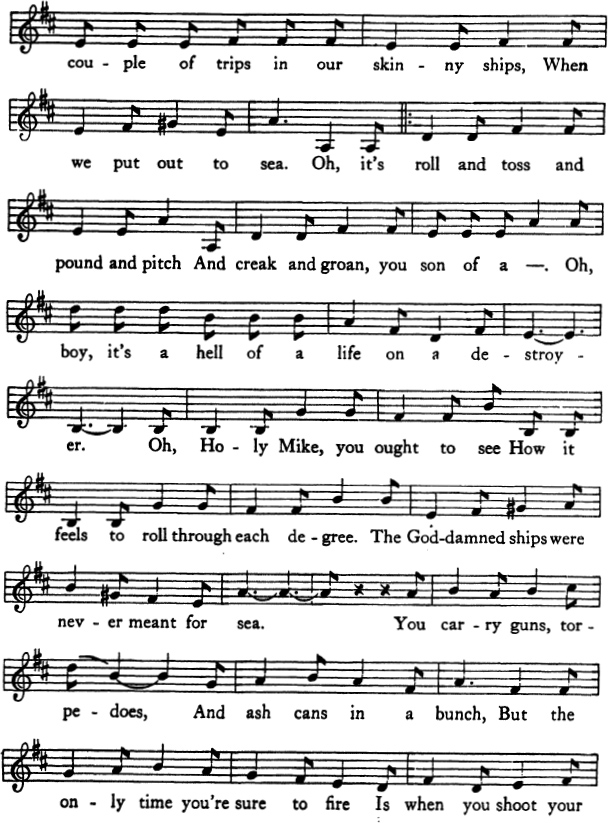

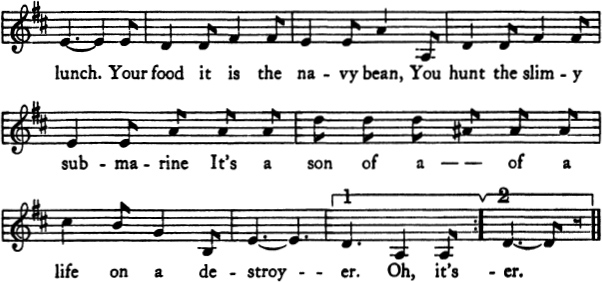

DESTROYER LIFE *

This song was shouted out at mess by the officers and crew aboard U. S. Destroyer Murray, on foreign service, 1917 to 1919.

Have got a lot to say

Of the hardships and the sorrows

That come the soldier’s way.

But we destroyer sailors

Would like their company

On a couple of trips in our skinny ships,

When we put out to sea.

Chorus:

Oh, it’s roll and pitch

And creak and groan, you son of a bitch.

Oh, boy, it’s a hell of a life on a destroyer.

Oh, Holy Mike, you ought to see

How it feels to roll through each degree.

The God-damned ships were never meant for sea.

You carry guns, torpedoes,

And ash-cans in a bunch,

But the only time you’re sure to fire

Is when you shoot your lunch.

Your food it is the navy bean,

It’s a son-of-a-bitch of a life on a destroyer.

We’ve heard of muddy dug-outs,

Of shell holes filled with slime,

Of cootie hunts and other things,

That fill a soldier’s time.

But believe me, bo, that’s nothing,

To what it’s like at sea,

When the barometer drops

And the clinometer hops,

And the wind blows dismally.

* The descriptive paragraphs and the shanty are quoted from Joanna Colcord’s Roll and Go (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co.).

* From Allen, Ware, and Garrison’s Slave Songs of the United States (New York: Peter Smith)

* We are indebted for words and air to Carl Sandburg and through him to Robert Frost. Three stanzas are quoted from the Post Statesman of San Francisco.

* The tune and the first three stanzas are quoted from Ballads and Sea Songs from Nova Scotia, by Roy W. Mackenzie (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press); the final three stanzas, from Capstan Bars, by David W. Bone (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.).

* The paragraph and the song are quoted from Joanna Coleord’s Roll and Go (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co.).

* From Carl Sandburg’s The American Songbag (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.).

* This song was sung and written down by John Thomas, a Welsh sailor on the Philadelphian, in 1896.

* From William Doerflinger, New York City.

* From Joanna Colcord’s Roll and Go (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co.).

* The correspondent in Missouri who sends this, wishing his name not to be published, writes: “My father, from whom I learned the ballad, had forgotten the last verse.” The air is from Shay’s More Drunken Friends and Pious Companions (New York: Macaulay Company).

* Tune is from Joana Colcord’s Roll and Go (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merill Co.).

* Sent by R. W. G. Vail, Ithaca, N. Y. Copied from an old newspaper, Brother Jonathan, published by Wilson and Company, New York, July 4, 1845, to tune of “Boyne Water.” This version is as sung in the theater at Albany in the character of a Negro sailor.

* From Seven Seas, September, 1915. Author unknown.

* Reprinted by permission of the copyright owners from Songs My Mother Never Taught Me, by John J. “Jack” Niles, Douglas S. “Doug” Moore, and A. A. “Wally” Wallgren, published and copyrighted 1929 by The Macaulay Company.