CHAPTER 1

AN INDEPENDENT SERVICE

1918 - 1922

A Fairy IIIF of 267 Squadron is hoisted aboard the seaplane carrier HMS Ark Royal in the early 1920s. The fledgling RAF inherited all of the commitments of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), including the provision of aircraft and flying personnel to support naval operations. HMS Ark Royal was closely involved with the deployment of RAF aircraft to Russia, Turkey and Somaliland in the immediate post-war years. (Jarrett)

In late 1917, air power throughout the British Empire was exercised by the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) and the Army Royal Flying Corps (RFC). Each arm had its own command structure and was serviced by its own procurement and supply chain. As might be expected, the RNAS was mainly a maritime force, operating both land and seaplanes, as well as flying boats, balloons and airships from coastal bases around the UK, but with units also based on the north coast of France and in the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas. Additionally, naval seaplane carriers gave the RNAS the mobility to operate further afield (such as East Africa and the Far East) if needed. RNAS aircraft were mainly employed for anti-submarine operations and coastal reconnaissance, but there was also a small number of fighter and bomber aircraft based in both France and the Aegean. The main bulk of the RFC was deployed on the Western Front in France and Belgium, but RFC squadrons also supported the army in Italy, Greece, Palestine, Mesopotamia and India. A handful of fighter squadrons were retained in the UK for home defence against German heavy bombers and Zeppelins (airships); another small number of bomber squadrons in France were positioned for independent operations over Germany; all other front-line RFC flying squadrons were allocated to the army at division level in each theatre of operations. These units were divided into ‘Army’ and ‘Corps’ squadrons. The Army squadrons comprised fighter units, tasked with achieving air superiority over the enemy air services, and bomber units tasked with attacking military targets such as headquarters units and similar facilities behind the enemy frontlines. The Corps squadrons were chiefly used for artillery observation and photographic reconnaissance, which were, perhaps, the two least glamorous yet most important and successful of the roles fulfilled by aircraft during the entire war. During army offensives, Corps aircraft would also be used for ‘contact patrols’ in which they would fly low over the battlefield to establish the positions of the forward army units and report them back to headquarters.

However, the failure of both air arms to stop the German air service from bombing the British mainland in 1917 led to serious questions about how the UK should be defended by its own air forces. These led to the larger question as to how British air power should be organized, and the man tasked by the government to answer all of those questions was J.C. Smuts, a South African lawyer who had distinguished himself fighting the British army during the second Boer War.

GENERAL SMUTS

Jan Christiaan Smuts was, by almost any measure, a genius: Albert Einstein is reputed to have numbered Smuts amongst the handful of people who actually understood his general theory of relativity and he was also named, along with Milton and Darwin, as one of the three outstanding graduates over five centuries at Christ’s College, Cambridge. In 1917, Smuts, who was at the time both a Lieutenant General in the British army and a leading member of the South African government, was invited to join the Imperial War Cabinet. On 11 July 1917, Smuts was tasked to examine, firstly, the arrangements for the defence of the British Isles against air raids and, secondly, ‘the air organization generally and the direction of aerial operations’. In a report published later that month, Smuts addressed the first subject, but wrote that ‘the second subject of our enquiry is the more important and will consequently require more extensive and deliberate examination.’ His second report followed a month later.

While Smuts acknowledged, in his second report, that the separate RNAS and RFC had grown from the perception that air power would be subordinate to the needs of the navy and the army, he wrote that ‘unlike artillery, an air fleet can conduct extensive operations far from and independently of, both army and navy… and the day may not be far off when aerial operations with their devastation of enemy lands and destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale may become the principal operations of war, to which the older forms of naval and military operations may become secondary and subordinate.’ He concluded that an Air Ministry should be established without delay and that the RNAS and RFC should be amalgamated into a single independent air service. The recommendations made by Smuts were accepted and the Royal Air Force (RAF) was formed from the RNAS and the RFC on 1 April 1918. Thus, Jan Smuts became the progenitor of the world’s first independent air force.

Unfortunately, the first appointee to the post of Chief of the Air Staff (CAS), Major General Sir H.M. Trenchard KCB, DSO, suffered a personality clash with Lord Rothermere, the Air Minister, and he resigned; his place was taken on 12 April by Major General F. H. Sykes CMG, who steered the new service through its first year of existence.

A GLOBAL REACH

From its inception, the RAF was involved in operational flying on a front that stretched from Ireland across to India. In fact, in April 1918 the last campaign of the war in India (in Baluchistan) was coming to a close and the resident units in India, 31 and 114 Squadrons, (which were both equipped with BE2e aircraft) saw no further action during the year. However, further west of them, the RAF units in Mesopotamia were very active in the late spring of 1918 as British forces in the region advanced northwards along the River Tigris, driving the Turkish forces back towards Kirkuk. The RAF contingent comprised two Corps squadrons, 30 and 63 Squadrons, operating the RE8 and a single Army squadron, 72 Squadron, which was equipped with the Bristol M1C Monoplane Scout, Martynside G.100 and SE5a fighters and also de Havilland (DH) 4 bombers. Although it was primarily intended for air-to-air work, the Bristol Monoplanes proved particularly effective at this time for ground strafing the retreating Turkish forces.

Wearing the uniform of a Field Marshal, the South African statesman, scholar and soldier Jan Christiaan Smuts (1870 –1950), whose report Air Organisation and the Direction of Aerial Operations, published in August 1917, was the catalyst for the establishment of an independent Royal Air Force the following year. (Official Photographer/IWM/Getty)

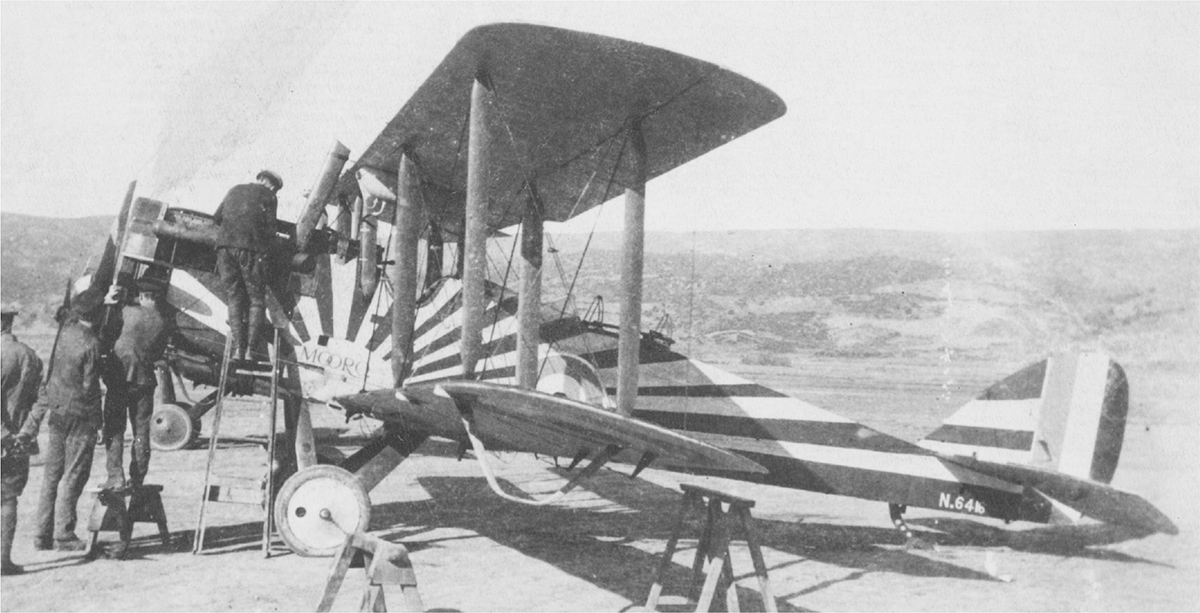

An Airco de Havilland DH4 day bomber of 475 Flight (later 220 Squadron) at Imbros. The unit carried out anti-submarine patrols over the Aegean Sea, as well as bombing raids over the Dardenelles and Salonika. (Jarrett)

The Turkish armies were also fighting a defensive battle in Palestine, having retreated from Gaza during the winter of 1917. In April 1918, the frontlines had stabilized, temporarily, just to the north of Jerusalem while the British forces re-grouped. After struggling with barely adequate aircraft in the previous year, the RAF units in-theatre had been recently re-equipped with more modern types: the Corps units, 14 and 113 Squadrons, now flew the RE8 while 142 Squadron operated the Armstrong-Whitworth (AW) FK8; additionally two fighter squadrons, 111 Squadron and 1 Squadron Australian Flying Corps (AFC), were equipped with the SE5a and Bristol F2b respectively. Another two squadrons, 144 Squadron (DH9) and 145 Squadron (SE5a) would join the frontline during the summer. All of these units were supplemented by ‘X’ Flight, a small independent flight which operated directly in support of Arab forces led by Col T.E. Lawrence. Unlike Mesopotamia where there was little air opposition, the RAF aircraft had often been engaged by Turkish or German fighters over Palestine; however, the advent of the SE5a and Bristol F2b in early 1918 meant that the balance of air superiority had tipped decisively towards the RAF. Apart from directing a sustained campaign of artillery counter-battery work, one of the major tasks of the Corps squadrons in Palestine was to photograph the terrain: there were virtually no maps of the Levant so the army depended on aerial surveys in order to produce suitable charts. The squadrons of the Palestine Wing were also active supporting army operations against the Turkish forces and transport infrastructure to the east of the River Jordan: the tasks carried out included contact patrols, tactical reconnaissance, bombing and aerial resupply of medical equipment.

RAF units were also busy in the eastern Mediterranean: seaplanes based in Malta, Santa Maria di Leuca (southern Italy), Crete, Port Said and Alexandria (Egypt) carried out routine anti-submarine patrols and convoy escort duties and there were two maritime wings, each comprising four squadrons of DH4s and Sopwith Camels based in southern Italy and the Aegean. Much like the work of the land-based Corps squadrons, the tasks carried out by the seaplane units were not particularly glamorous, but they were very effective in limiting the effectiveness of the Austro-Hungarian U-boat service. The DH4 and Camel units based in Italy at Otranto (224 and 225 Squadrons) and Taranto (226 and 227 Squadrons) were used for attacking naval and military targets on the Adriatic coast of Albania and Montenegro. From April to late August, they bombed the submarine bases at Cattaro and Durazzo frequently and the same squadrons were also used to support the Italian offensive in Albania in early July 1918. In the Aegean sector, the four land-based units were more widely dispersed across eastern Greece and the north Aegean islands: 220 Squadron was based at Imbros, 221 Squadron at Stavros, 222 Squadron at Thasos and 223 Squadron at Mudros. Apart from anti-submarine patrols of the Aegean and reconnaissance patrols over the Sea of Marmaris, these units bombed targets in the Dardanelles region as well as carrying out bombing and reconnaissance sorties over the Salonika (or Macedonia) front.

In April 1918, the Salonika front was formed as an approximately 50-mile arc around the city of Thessaloniki: here an Allied force was dug in, facing combined Turkish, Bulgarian and Austro-Hungarian armies. Following the pattern in Mesopotamia, the RAF contingent in Thessaloniki comprised two Corps squadrons, 17 and 47 Squadrons (both with FK8s and DH9s) and a single Army squadron, 150 Squadron (equipped with the SE5a, Bristol Monoplane M1 and Camel). Often working in co-operation with 221 and 222 Squadrons, and enjoying the air superiority won by the fighters, the aircraft of 17 and 47 Squadrons were used to bomb airfields and storage depots deep behind the enemy frontlines throughout May.

A Bristol M1C Monoplane fighter, on an airfield near Baghdad in 1920. Fast and manoeuvrable, this type was used very effectively during 1918 by 72 Squadron in Mesopotamia and by 47 and 150 Squadrons in Salonika. Although 125 of these aircraft were ordered, it seems likely that less than 20 saw active service, largely because of a general prejudice within the RFC and RAF against monoplanes. (Flintham)

Further north, and on the opposite side of the Adriatic Sea, a British contingent fought alongside Italian troops on the Piave front in northeast Italy. They were supported by a somewhat substantial air arm based to the northwest of Padua, comprising 34 Squadron (RE8) at Villaverla, 66 Squadron (Camel) at San Pietro-in-Gu and two more Camel squadrons, 28 and 45 Squadrons, at Grossa; a further flight of Bristol F2b, which was later to become 139 Squadron, was attached to 34 Squadron to help with the task of routine reconnaissance. The Camel squadrons were tasked to escort the RE8 reconnaissance aircraft and also to carry out offensive patrols against Austro-Hungarian aircraft. In May, it became apparent that an offensive by the Austrians was imminent and on 30 May a force of 35 Camels carried out a pre-emptive low-level bombing attack on enemy hutments in the Val d’Assa area. When the offensive was launched in mid-June, the RAF sent large formations of Camels, again operating at low level, which were effective in helping to repel the attack.

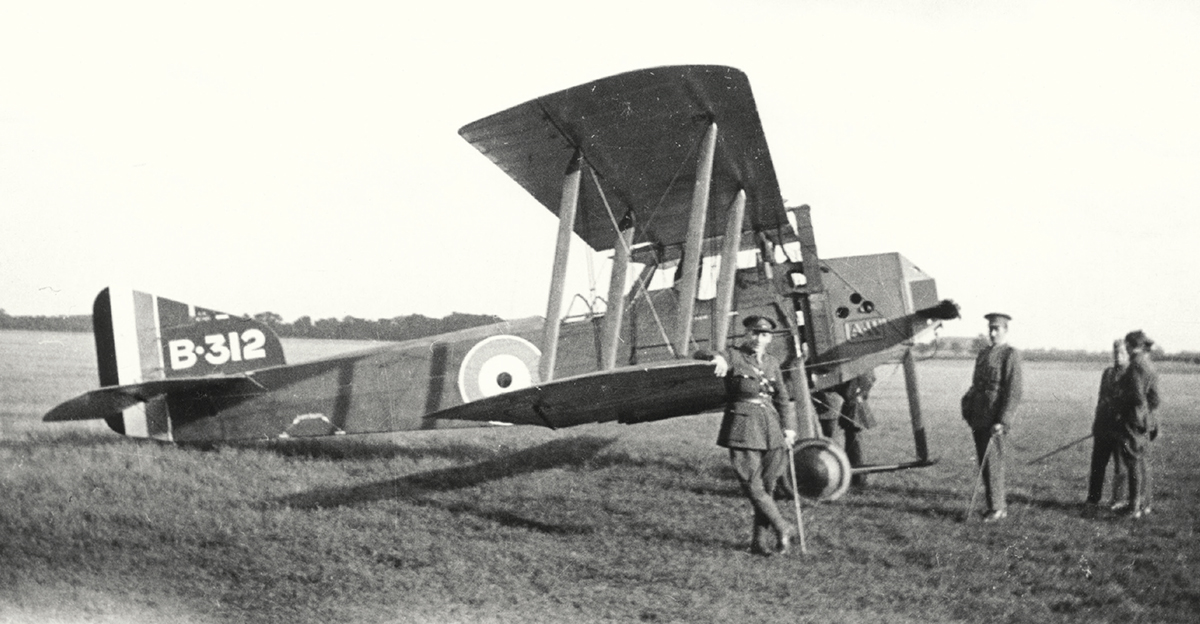

Probably the most successful aeroplane produced by the Royal Aircraft Factory, the SE5a fighter aircraft along with the Sopwith Camel enabled the RAF to establish air supremacy over the Western Front. The type also served in the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern theatres. This particular aircraft was flown by Maj Fred Sowrey MC, while commanding 143 Squadron, a home defence unit. (Pitchfork)

THE HOME FRONT

In 1918, home defence of the UK against enemy aircraft was provided by an integrated system of anti-aircraft guns, searchlights and fighter aircraft, served by a rudimentary early warning system. The latter was provided by observer stations manned by the police of the Observation Corps, sometimes backed up by wireless-equipped aircraft which could relay the position and altitude of enemy aircraft. The RAF contribution to the Home Defence organization was divided into a Northern and a Southern Group, covering the areas to the north and south of the Wash. The northern group comprised five squadrons equipped with Bristol F2b and Avro 504K aircraft, while the southern group mainly focussed on the defence of London with 11 squadrons equipped with FE2b, SE5a, Bristol F2b, Camel and Avro 504K aircraft. After an absence of a month from the UK mainland, the Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte (German air service) carried out a raid on the Midlands with five Zeppelin airships on the night of 12/13 April. Taking advantage of poor weather which prevented many RAF fighters from taking off, the airships were untouched by the defences and were able to drop their bombs on targets including Wigan, Birmingham and Coventry. Only one interception was made, that of the Zeppelin L62 by Lt C.H. Noble-Campbell of 38 Squadron, but he was wounded and his aircraft damaged by the defensive fire from the Zeppelin, which escaped safely.

Another large raid by German aircraft took place on the night of 19/20 May. On this occasion, a force of 43 bombers, mainly Gotha and Giant aircraft, attacked Dover and London under the light of a full moon. This time the defences, which included 84 fighter aircraft, were much more effective and seven of the German bombers were brought down.

However, the greater part of the RAF’s operational strength in the UK was involved in anti-submarine operations around the coast. One surprisingly cost-effective measure introduced in the summer of 1918 was to use surplus DH6 training aircraft to patrol coastal shipping lanes. The presence of an aeroplane was usually enough to deter a U-boat commander from making an attack and submariners were unaware of the limited offensive capabilities of the DH6. Furthermore, as the aircraft was very simple to fly, it gave the opportunity for pilots who were unsuited to front-line flying (for example those with disabilities incurred in previous operational flying) to continue to be useful to the service. Seaplanes were also used for anti-submarine work and coastal patrols, while larger flying boats carried out long-range reconnaissance sorties along the German and Dutch coasts. They were also used for long-range interception of enemy airships: the Zeppelin L62, which had evaded the home defences in April, was destroyed after being attacked off Heligoland on 10 May 1918 by an RAF flying boat.

The distinctive silhouette of a Blackburn Kangaroo anti-submarine patrol aircraft of 246 Squadron, escorting a naval convoy. Despite its ungainly appearance, the type proved to be particularly effective in the anti-submarine role: despite being deployed only in small numbers in the last six months of the war they attacked eleven U-boats. Unfortunately, the value of long-range maritime patrol aircraft was forgotten after the war and had to be re-learnt during World War II. (Cross & Cockade)

The Felixstowe F2A flying boat equipped seven squadrons during World War I and was used for patrols over the North Sea. The aircraft carried a crew of four and had an endurance of some 6 hours. Despite its large size (including a wing span of nearly 100ft), the Felixstowe F2A was a remarkably manoeuvrable aeroplane and was capable of combat against enemy fighters and flying boats as well as Zeppelins and submarines.

Only some 14 Blackburn Kangaroos were built, of which ten served with 246 Squadron at Seaton Carew, near Hartlepool, during 1918. The aircraft was powered by two Rolls-Royce Falcon II engines and carried a crew of four, who enjoyed good visibility from the two open cockpits. (Jarrett)

Most of the 8,000 Avro 504 aircraft built during World War I were used as training aircraft, but in 1918 some 200 of the type were converted as single-seat night fighters. These aircraft equipped six home defence squadrons. (Jarrett)

The coastal waters off the Netherlands and Germany were the scene of almost continuous action between German seaplanes and RAF seaplanes and flying boats, as the Luftstreitkräfte sought to prevent RAF aircraft from interfering with mine clearance operations. One of the largest actions was fought on 4 June 1918 between five RAF Felixstowe F2A flying boats (two from Felixstowe, Suffolk and three from 228 Squadron at Great Yarmouth, Norfolk) and approximately 15 German seaplanes based on the island of Borkum; although the two flying boats from Felixstowe were lost in the combat, six enemy seaplanes were shot down in this action.

On the continental side of the Strait of Dover were the two naval wings at Dunkirk, one of which comprised a fighter unit (213 Squadron), an anti-submarine unit (217 Squadron), and a reconnaissance unit (202 Squadron), the other of which consisted of a fighter unit (204 Squadron), a day bomber unit (211 Squadron) and three night bomber units (207, 214 and 215 Squadrons). The latter wing was intended for operations against the German U-boat, motor gunboat and seaplane bases at Ostend and Zeebrugge; they remained active in doing so throughout the rest of the war. They also supported the naval raids on Zeebrugge on 23 April and Ostend on 10 May. Another two naval fighter squadrons (201 and 210 Squadrons) had been transferred from Dunkirk to the Western Front at the end of March to reinforce the hard-pressed squadrons. Other former naval fighter squadrons had preceded them, including 209 Squadron, which was involved in the shooting down of Manfred von Richthofen (‘The Red Baron’) on 21 April.

Due to the powerful gyroscopic effect of its heavy rotary engine and a centre of gravity well forward in its short fuselage, the Sopwith 1F.1 Camel enjoyed what one test pilot described as ‘very lively handling characteristics.’ Extremely manoeuvrable and armed with two forward-firing Vickers machine guns the Camel was perhaps the most successful RAF fighter aircraft of World War I. By October 1918, the RAF had over 2,500 Camels on strength. (Flintham)

THE WESTERN FRONT

The RAF was born into the aftermath of the German spring offensive on the Western Front, which had broken through Allied lines in the Somme area on 21 March 1918. As the army staged a fighting retreat, RAF aircraft were instrumental in slowing the German advance. On 1 April, all single-seat fighter units in V Brigade were involved in almost continuous low-level bombing and strafing attacks on enemy troops; meanwhile the Corps squadrons carried out contact patrols in order to establish the positions of friendly ground units. The main role of these units, though, was to co-ordinate artillery fire, but it proved to be a difficult task when many batteries either abandoned their wireless equipment, or did not re-erect their aerials when they moved to new positions. The day bomber units were also busy on that day, attacking targets in the enemy rear areas: 205 Squadron bombed enemy aerodromes, while 18, 57 and 206 Squadrons concentrated on the railway stations at Cambrai, Bapaume and Menin. Air activity continued into the night, with attacks by 58 and 83 Squadrons on the railway system and 101 and 102 Squadrons attacking road transport travelling under headlamps. A Handley Page O/100 bomber of 214 Squadron also dropped 14 bombs on Valenciennes that night. Similar operations continued through 2 April, and although Marshal Foch issued an order that ‘the first duty of fighting aeroplanes is to assist the troops on the ground by incessant attacks,’ the RAF policy remained that artillery direction was the prime role and that at least some fighter units should be used to protect the Corps and ground-attack aircraft from the attentions of enemy aircraft. Indeed, the following day, force of some 30 Pfalz and Albatros fighters bounced Camel and SE5a fighters at 1,500ft near Rosières. Five German aircraft were shot down during the engagement, at no cost to the RAF squadrons, and thereafter, as a result of this action, continuous patrols, each of two-squadron strength, were mounted by the RAF specifically to seek out and destroy enemy aircraft.

An Airco de Havilland DH9 bomber in flight. Intended to replace the DH4 as a day bomber, the DH9 was handicapped by the mediocre performance of the 230hp Siddeley Puma engine. Nevertheless, some 3,200 of these aircraft were built and they saw action with RAF units in France, the Mediterranean and the Middle East. (RAFM)

The German advance in the Somme area was halted just to the east of Amiens two days later, but no sooner had that part of the line been secured, than a second offensive (Battle of the Lys) was launched in Flanders. On 9 April, after an initial bombardment of chemical shells, German forces advanced along a front from Armentières to Festubert. The advance was covered by thick fog which prevented RAF aircraft from taking off during the morning. After being warned that German forces were about to overrun the aerodrome at La Gorgue, the resident 208 Squadron burnt their Camels before abandoning the base. The fog lifted into low cloud in the early afternoon and a contact patrol by an RE8 from 4 Squadron revealed the positions of German troops, enabling low-level attacks against them by Camels of 4 AFC, 203, and 210 Squadrons and the SE5a aircraft of 40 Squadron. Poor weather continued the following day, which also saw a second German thrust developing opposite Messines. When the weather cleared sufficiently, the low-level attacks by RAF fighter squadrons resumed, as did the work of the Corps squadrons, but these operations were complicated by the presence of low-flying German aircraft over the battlefield. Like their counterparts in the Somme area, the day bomber squadrons operated behind the German lines throughout the day attacking the rail infrastructure and reinforcements. As darkness fell most airfields became fog-bound, which limited the activities of the night bombing units; nevertheless, bombers were able to carry out night attacks on 10/11 April. The next day, with the ground situation critical, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig issued the order that ‘every position must be held to the last man; there must be no retirement. With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause, each one of us must fight on to the end.’ Indeed, 12 April proved to be the pivotal day of the battle, during which RAF fighter aircraft carried out many low-level attacks while Corps aircraft ensured effective gun direction and contact patrols. During the day six German observation balloons were destroyed and that night, the bomber squadrons were active again attacking rail and road transport as well as troop billets. After fierce fighting, the German advance lost momentum and slowed: the frontline in Flanders was eventually stabilized by 29 April.

Further German offensives followed in May, June and July in the largely French-held sectors in Champagne and the Chemin des Dames. In early June eight RAF units, comprising three DH9 day bomber squadrons and five fighter squadrons were dispatched to the area to help to contain the German advance. From 9 to 10 June these aircraft were used primarily for low-level gun and bomb attacks on advancing German troops, and from 11 June they also supported the successful French counterattack that followed at Noyon.

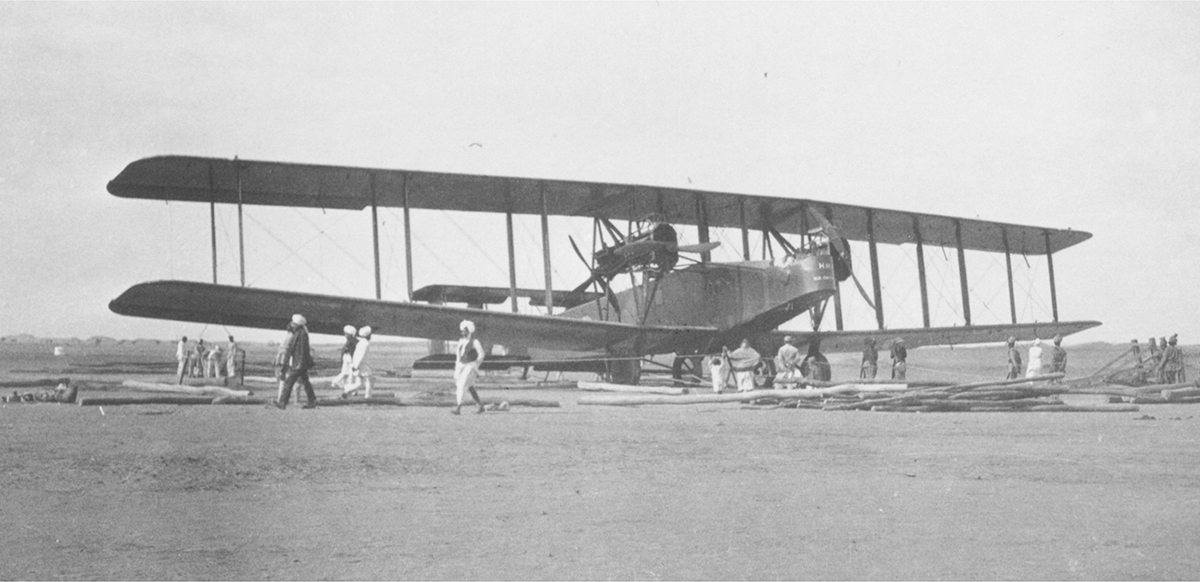

Handley Page O/400 heavy bombers, of which some 550 were built, saw service with seven squadrons in France, including 97, 115, 215 and 216 Squadrons of the Independent Force. The largest aeroplane operated by the RAF in World War I, it could carry a weapons payload of 2,000lb including the largest 1,650lb ‘SN’ bomb. (Flintham)

INDEPENDENT OPERATIONS

A wing of bomber aircraft had been established at Nancy-Ochey in late 1917 in order to attack targets in Germany: these operations were intended as a reprisal against German air raids on the British mainland. The wing initially comprised 55 Squadron with the DH4 for day operations, and 100 Squadron equipped with the FE2b also 16 (Naval) Squadron (which became 216 Squadron) equipped with the Handley Page O/100 and O/400 for night operations; it was enlarged in May 1918 by the addition of 99 and 104 Squadrons flying the DH9. From Nancy, the RAF aircraft could reach into Germany to cover an arc from Köln (Cologne) to Stuttgart: operating within that area whenever the weather was suitable, they attacked factories, military barracks and railways by both day and night. For night operations, steelworks made the best targets, as the blast furnaces showed up clearly in the dark. The wing officially became the Independent Force in June 1918, recognizing that the operations were strategic in nature and were independent of land operations; it was further expanded with the addition of 110 Squadron, equipped with the DH9 and 97, 115 and 215 Squadrons with Handley Page O/400 bombers. Although operations by the Independent Force caused relatively little physical damage in Germany, it was considered that they had been effective in undermining the morale of the civilian population. Night operations were also carried out against German airfields, but the results of these attacks were inconclusive.

However, German night operations against RAF aerodromes, and other military facilities, in France in early 1918 were successful and they resulted in the transfer of night-fighter squadrons to France. Of these, 151 Squadron, equipped with the Sopwith Camel, which arrived in June, proved to be particularly effective: in the five months after arriving in France it shot down some 26 German night bombers without any losses.

By August, the German night bombing campaign against Britain had ground to a halt, not least thanks to the effective anti-aircraft defence system. The last raid by the Luftstreitkräfte was on the evening of 5 August, when five Zeppelin airships approached the coast of East Anglia. They were intercepted by a DH4 from Yarmouth flown by Maj E. Cadbury with Capt R. Leckie, who destroyed Zeppelin L70; seeing this engagement, the remaining airships then turned and headed back to Germany; no bombs were dropped on the mainland.

In the summer of 1918, various schemes were tried to improve the tactical range of aircraft operating over the North Sea. Attempts to tow or carry seaplanes proved too dependent on sea conditions, but trials using a Sopwith Camel 2F.1 flying off a lighter towed by a destroyer were successful. On 11 August 1918, Lt S.D. Culley launched from a lighter towed by HMS Redoubt and shot down Zeppelin L53. (Flintham)

Another Zeppelin, the L53, was destroyed six days later. The previous evening a small naval force comprising light cruisers and destroyers had sailed for the Dutch coast. Three of the destroyers each towed a lighter (small barge), carrying an aeroplane as a means of giving the machine a longer tactical range. Two of these aircraft were flying boats, but a lighter from HMS Redoubt carried the Sopwith Camel to be flown by Lt S.D. Culley. The following morning, near the island of Terschelling, a formation of Yarmouth-based flying boats reported the presence of a Zeppelin and Culley was launched to make an interception; this he successfully did and then shot down the airship. As it was not possible for him to land back on the lighter he ditched his Camel in the sea and was picked up by a naval ship.

RUSSIA

A modest task force, including an RAF contingent comprising eight DH4 bombers, five Fairey Campania seaplanes and two Sopwith Baby seaplanes, had been dispatched to northern Russia in May 1918. Its purpose was twofold: firstly, to secure the British military equipment which had been provided to the Russian army and prevent it from falling into Bolshevik hands, and secondly, to support White Russian forces. After arriving in Murmansk, the force split into two: ‘Syren’ Force set up the defence of Murmansk and the air arm started operations in support of White Russian forces along the railway line which ran southwards to Kandalaksha via Kem and Lake Onega. Meanwhile ‘Elope’ Force moved on by ship towards Arkhangelsk. After a brief action, which included bombing Bolshevik artillery on Modyuski Island by Fairey Campania floatplanes of the RAF, Arkhangelsk was taken on 7 August. Here the RAF contingent found enough new (still in their delivery crates) Sopwith 1½ Strutter aircraft to form two squadrons, which were manned by RAF and Allied personnel. Once again, DH4 bombers and seaplanes were used for operations along the railway line (which led to Moscow) and the River Dvina. The aircraft of both the Syren and Elope forces were used for long-range reconnaissance and artillery observation, but also carried out bombing attacks against Bolshevik ground forces.

The Martinsyde G 100 Elephant entered service with the Royal Flying Corps in early 1916, but by 1918 only a handful of the type remained in service, with 72 Squadron in Mesopotamia. In May 1918, two of these aircraft were attached to ‘Dunsterforce’ a British Army detachment which attempted to hold the city of Baku against Turkish forces. (RAFM)

Further south in the same month, two Martinsyde G100 aircraft of 72 Squadron were dispatched from Iraq to support ‘Dunsterforce,’ a British army detachment which was holding Baku against Turkish forces. The aircraft began operations on 20 August and were fortunate in having no enemy air opposition. They were initially used for reconnaissance, bombing and leaflet dropping, but also carried out intensive low-level strafing attacks against enemy troops during the Turkish offensive which started on 26 August. However, the Turkish force was overwhelming and despite a spirited rear-guard action covered by the aircraft of 72 Squadron, the inevitable evacuation took place on 14 September, after the aircraft had been burnt.

The Armstrong Whitworth FK8, known as the ‘Big Ack’ was used by 8 Squadron in the first co-ordinated actions by tanks and enemy aircraft during the Allied offensive of August 1918. Although it was superior in many ways to the RE8, the FK8 was only produced in relatively small numbers and equipped just five squadrons in France, and a further three in Macedonia and Palestine. (Jarrett)

The distinctive ‘backward stagger’ of the wings of the Sopwith 5F1 Dolphin is clearly visible in this view. The type saw service in France with 19, 23, 79, 87 and 90 Squadrons.

An RE8 of 59 Squadron over the Western Front. Aircraft from this squadron were tasked with artillery spotting and direction during the offensive, but the crews frequently took direct action to support infantry troops. On 23 August 1918, the crew of an RE8 from the squadron strafed and neutralized an enemy machine gun position which had halted the advance of the New Zealand Division to the west of Bapaume. (RAFM)

AUGUST OFFENSIVE

After the unsuccessful attempts by the German army to break through on the Western Front in the spring, it was the turn of the Allied forces to attack in late summer 1918. The British offensive opened near Amiens in the thick mist of the morning of 8 August. Just as it had in the German offensive five months earlier, the mist prevented aircraft from operating over the battlefield until late morning; however, as the weather cleared, single-seat pilots found that the ground was rich with targets. Meanwhile, the swift advance of British and Empire forces made artillery direction by the Corps aircraft challenging as friendly troops began to advance beyond the range of the guns; in this fluid situation, contact patrols became even more important as the only means to keep track of the positions of ground units. The Corps aircraft were also tasked with some new roles: the RE8 aircraft of 3 AFC, 5, and 9 Squadrons dropped phosphorous bombs to provide smoke screens for the Australian and Canadian Corps as they attacked German strongpoints, while the FK8 aircraft of 8 Squadron experimented with close support of tanks. At this stage co-operation was limited to locating tanks, and dropping messages at the brigade headquarters notifying the staff of their progress; later tank contact patrols would also engage German anti-tank guns with bombs and machine-gun fire.

By late afternoon on the first day of the offensive, a large German force was trapped by the River Somme where it curves south at Péronne. The bridges over this stretch of river formed choke points and the RAF bomber squadrons were tasked with the destruction of the 12 bridges between Péronne and Offoy. That evening and throughout the next day, RAF squadrons fought a sustained campaign against the Somme bridges: DH9 and DH4 bombers, supported by Camel and SE5a patrols, carried out numerous bombing attacks. On the first afternoon 205 bombing sorties were flown, but they were hotly contested by an increasingly aggressive Luftstreitkräfte, which resulted in the RAF losing 45 aircraft and a further 52 wrecked. At night, follow-up attacks were flown by FE2b night bomber squadrons and the Camels of 151 Squadron. On 9 August, the bombing missions started again at 05:00hrs and carried on throughout the day, culminating in a simultaneous attack by four DH9 squadrons against five bridges in the evening. This latter mission was directly supported by an offensive patrol comprising Sopwith Dolphin, Bristol F2b, SE5a and Camel squadrons; when darkness fell, night attacks continued, including bombing of the bridge at Voyenne by 207 Squadron equipped with the Handley Page O/400. However, it soon became apparent that despite significant air effort, little damage had been done to any of the bridges. The reasons for this were twofold; firstly, although some of the bombs were delivered from heights of around 2,000 or 3,000ft, most of the bombing had been carried out from 11,000 or 12,000ft, from which altitude bombing was not accurate enough to hit a target as small as a bridge. Secondly, even if hits were scored, the 25lb and 112lb bombs were too small to cause any significant damage to such a robust structure.

On 10 August, the bombing squadrons’ attentions were switched to the more realistic objective of disrupting the railway traffic at Péronne and beyond. The first raid was carried out by 12 DH9s, escorted by a formation of 40 Camels and Bristol F2bs and seven SE5as. This sizeable formation was attacked over the target area by a force of 15 Fokker DVIIs and although one German fighter was shot down, five British aircraft were lost. The railway bombing continued into the night and on through the following day. By then the British advance had slowed, but the German army had already commenced a general withdrawal eastwards.

The next thrust came in the Bapaume area on 21 August. Once again, poor weather limited the effectiveness of air power on the first day. However, the weather cleared as darkness fell and RAF night bombers were able to operate, concentrating on the enemy airfields; the following morning, the day bomber squadrons began to attack the railway lines fanning out from Cambrai. On 23 August, the main offensive began along a wider front between Péronne and Bapaume. One innovation was the establishment of a Central Information Bureau (CIB) which acted as a reporting point for wireless-equipped Corps aircraft: the idea was that ground targets would be identified for low-level ground strafing and the CIB would then pass that information on to the relevant fighter aerodromes for action. Another innovation, which had been frustrated by the weather two days earlier at Bapaume, was the use of a fighter squadron (73 Squadron) to support tanks in combat by attacking German anti-tank guns. As in previous offensive actions, other fighter squadrons were tasked with supporting the infantry by making low-level attacks on the battlefield. Also the Corps aircraft often found that the quickest way to support the troops on the ground was by taking a direct role in engaging enemy machine-gun posts. Meanwhile, the railway system and road transport in the German rear area received the full attention of the day and night bomber squadrons. The weather was poor for much of the next few days and nights, but low-level attacks continued as well as the work of the Corps squadrons, often in driving rain under a 300ft cloud base; during this time RE8 aircraft were also regularly used to drop supplies of ammunition to troops in forward areas.

Further north, another assault was launched from Arras on 26 August, once again under low cloud and heavy rain. The weather prevented the day bomber squadrons from flying, but the Corps squadrons, 5 and 52 Squadrons, were active, flying at 200ft, while the Camel and the SE5a squadrons carried out close-support attacks. The following day the weather was little improved, but again the fighter squadrons were tasked with carrying out regular patrols at low level over the battlefield. Additionally, 73 Squadron continued its work of neutralizing anti-tank guns in the path of the advancing tanks. By the end of August, the German army had been pushed back almost to the Hindenburg Line.

However, one major obstacle remained: the Drocourt–Quéant Line. This 15-mile stretch of defensive fortifications, which was centred approximately seven miles east of Arras, was the objective for two Canadian and one British division on 2 September. The infantry was supported by low-flying Camels of 54, 208 and 209 Squadrons and SE5a fighters of 64 Squadron, while the artillery was directed by the RE8 aircraft of 4, 6, and 52 Squadrons and the tanks were supported by FK8s from 8 Squadron and Camels from 73 Squadron. The result was an almost continuous presence of aircraft operating at low level over the battlefield. By dusk the German line had been broken and that night the enemy troops fell back to the line of Canal du Nord.

An RE8 over the Jerusalem to Bireh road. During the Battle of Megiddo in Palestine, which began on 19 September 1918, the aircraft of 14 Squadron and the FK8 aircraft of 142 Squadron carried out artillery direction and tactical reconnaissance; they also participated in the decimation of the Turkish 7th Army in the Wadi Fara – which remains a definitive example of the destructive capability of air power. (14 Squadron Association)

MACEDONIA & PALESTINE

As the British armies in France were poised to attack the Hindenburg Line in mid-September 1918, those in Macedonia and Palestine were also about to commence major offensives. The first of these was in Macedonia, when British and Greek forces attacked the Bulgarian positions to the west of Lake Dojran on 18 September. The ground forces were supported by 17 and 47 Squadrons; both units operated a mixture of FK8 and DH9 aircraft and fulfilled the corps, reconnaissance and bombing roles. They in turn were protected by Camels and SE5a fighters of 150 Squadron. Two days of heavy fighting followed, during which RAF aircraft carried out low-level bombing and strafing attacks, but their crews found it difficult to observe much detail because of the smoke and dust on the battlefield. Artillery direction against enemy batteries was more successful, as were attacks by the DH9 bombers against equipment dumps in the enemy’s rear areas. The only appearance over the battlefield by Bulgarian aircraft was swiftly repelled by 150 Squadron and thereafter the skies were uncontested. On the ground Bulgarian forces fought back fiercely and by 20 September it seemed that the Allied forces had made no progress. However, the following day, a DH9 returned from a reconnaissance patrol and reported that the Bulgarian army was withdrawing northwards en-masse. Aircraft were immediately detailed to bomb enemy troops and their transport and over the coming days the retreating Bulgarians were continuously harassed by RAF aircraft. Long-range reconnaissance flights were also mounted in an attempt to discover what exactly was happening behind the Bulgarian frontlines. On 28 September, a sizeable column of troops was found in the Kryesna Pass where it was subjected to sustained bombing and strafing attacks, resulting in many enemy casualties. This was the last action by the RAF in Macedonia: an armistice was signed by the Bulgarian government on 30 September and hostilities ceased on that front.

The offensive in Palestine (the Battle of Megiddo) began on 19 September. The SE5a fighters of 111 and 145 Squadrons had already established air supremacy over the area, so the German crews of the reconnaissance aircraft were unable to see the preparations for the assault. From early September, the Turkish army had been deceived into believing that the assault would be delivered in the Judean Hills on the eastern flank, rather than on the coastal plain. On the morning of the attack, the Turkish command and control channels were seriously disrupted by air attacks on their corps and divisional headquarters and military telephone exchanges. Handley-Page O/400 bombers from ‘X’ Flight attacked the telephone exchange at El Affule and this attack was followed up by another raid, this time by DH9 bombers of 144 Squadron. Earlier, this squadron had also attacked targets at Nablus, while 142 Squadron (FK8) and 14 Squadron (RE8) also carried out dawn raids. A standing patrol of two SE5a fighters over the Turkish aerodrome at Jenin throughout the day also ensured that enemy aircraft were unable to intervene. The British infantry attack quickly broke through the Turkish lines in the coastal sector. The main problem for the Corps squadrons was that the advance was so rapid that it quickly moved beyond the range of the artillery that they were directing. In the afternoon of 19 September, a large number of Turkish troops was discovered on the road from Tul Karm to Nablus and it was subjected to a prolonged attack by all of the RAF squadrons. Aircraft flew continuously along the column dropping bombs or grenades and machine-gunning any signs of movement. However, this massacre was only a rehearsal for an even greater slaughter two days later, when the Turkish 7th Army attempted to withdraw through the Wadi Fara, into the Jordan Valley. The entire army was caught in the Wadi on a narrow road which was bounded by a steep uphill slope on one side and a precipice on the other; with no means of escape, the Turkish troops were entirely at the mercy of RAF aircraft. Throughout the day, the troops were subjected to a relentless attack by all the aircraft that could be mustered. In the course of this attack, over 9 tons of bombs were dropped into the Wadi Fara. By the evening the Turkish 7th Army had been annihilated. The tactical emphasis now switched to the east of the River Jordan and the aircraft of 1 Squadron AFC and 144 Squadron bombed Turkish positions in support of the advance towards Amman; the city was captured on 25 September.

THE HINDENBURG LINE

The offensive against the Hindenburg line commenced on 27 September, with attacks by the 3rd Army on the northern flank and the 1st Army on the southern. Once again, the infantry assault was supported by low-level attacks by fighter aircraft, which in turn were protected from German aircraft by offensive patrols. German aircraft were also contained by bombing attacks on their aerodromes by the day bomber squadrons. The Corps squadrons of both armies were mainly involved with directing artillery counter-fire against German gun positions. An RE8 from 13 Squadron on a contact patrol found a formation of German infantry preparing for a counterattack and was able to call down artillery fire to neutralize the threat. That night, despite heavy cloud rolling in, the night bombers operated behind German lines attacking transport. The 4th Army, in the centre of the British line, opened its attack on the morning of 29 September. The ground forces included three tank brigades, which once again were supported by the FK8 aircraft of 8 Squadron and Camels of 73 Squadron. Flying conditions over the battlefield were difficult for the first days because of mist and cloud, mixed with smoke, but the weather improved on 1 October.

Further north, the Belgian army offensive (which included the British 2nd Army) had begun in Flanders on 28 September and once again low-level attacks by aircraft were integrated as part of the assault plan. Although there was no CIB on the Flanders front, Corps squadrons in this sector (7, 10 and 53 Squadrons) made good use of wireless (radio) equipment to pass on their reports. The aircraft were also used to drop rations to the forward troops at the end of the day. Through the rest of the month, the British, Empire and Allied forces continued to advance eastwards and the RAF units continued to support the army operations in the pattern that had been established so successfully.

The Royal Aircraft Factory RE8 was, arguably, the most important aircraft type in service with the RAF during the World War I. Known to its crews at the ‘Harry Tate’ after a music hall comedian of the day, the RE8 was the mainstay of the Corps squadrons, equipping a total of 19; the type saw active service in all theatres of operations. Over 4,000 were built to carry out the unglamorous but vitally important work of artillery direction and photographic reconnaissance. Although the type did not enjoy a particularly good reputation on the Western Front, it was regarded favourably in other theatres. (Pitchfork)

OCTOBER OFFENSIVES

At the beginning of October 1918, the frontline in Mesopotamia ran approximately east–west close to the south of Kirkuk and British forces were positioned on both sides of the River Tigris. The offensive began on the night of 23/24 October and the following morning reconnaissance patrols by 72 Squadron located Turkish forces retreating northwards. The campaign in Mesopotamia was more fluid than that in other theatres and the contact patrols by the RE8 aircraft of 63 Squadron assumed vital importance in feeding the army commanders with up-to-date information about the dispositions of friendly and enemy forces. Over the next five days the battle moved swiftly along the Tigris back towards Mosul until, on 31 October, the Turkish army in Mesopotamia surrendered.

In Palestine, the Turkish army had been routed at Megiddo and British and Empire forces advanced swiftly to take Damascus on 1 October. In order to keep some semblance of aerial contact with advancing cavalry units, 14 and 113 Squadron used their RE8 aircraft to ferry petrol and oil to a forward operating base at El Affule so that they could be used by the FK8 aircraft of 142 Squadron for reconnaissance sorties and contact patrols. On 25 October Aleppo was captured and on 31 October, Turkish forces capitulated.

In northern Italy, the Battle of Vittorio Veneto opened with an Allied push across the River Piave on 27 October. Mapping for the offensive had been produced from the aerial photographs taken by the Bristol F2b aircraft of 139 Squadron in the preceding days. The initial RAF participation in the battle was through contact patrols by RE8 aircraft of 34 Squadron, but as the Austrian resistance crumbled, the other squadrons were deployed in low-level attacks against the retreating enemy forces. Hostilities came to an end in Italy with the signing of an armistice by the Austria on 4 November.

Meanwhile the Allied armies in France and Flanders continued their advance. The German retreat was made more difficult by a campaign of bombing attacks (both day and night) against the railway system in occupied territory and the German border. The Luftstreitkräfte vigorously opposed the bombers, sometimes flying in formations of 50 fighters. The hardest day’s fighting in the air was on 30 October, when 67 German aircraft were destroyed, for the loss of 41 RAF aircraft. The RAF continued to bomb and strafe German troops over the next week until the war was ended by the armistice with Germany on 11 November 1918.

DEVELOPMENTS IN RUSSIA

Although the war against the Central Powers was now over, RAF units were still involved in combat operations in Russia. Over the autumn of 1918, the RAF in North Russia was bolstered by a flight of RE8s and six Camels. By October the various units from Murmansk were based on the northern tip of Lake Onega: DH4, RE8 and Camels were at Lumbushi (just north of the lake) while the seaplanes were at Medvegigora (on the northern tip of the lake); the Arkhangelsk units were split between ‘A’ Flight, covering the Moscow railway, at Obozerskaya on the railway 75 miles south of Arkhangelsk and ‘B’ Flight, covering the River Dvina, at Bereznik, along the river some 140 miles southeast of Arkhangelsk. Aircraft from all of these bases were operating in support of White Russian forces.

In early 1919, the scope of operations in Russia was increased with the dispatch of aircraft to support the British naval flotilla on the Caspian Sea in their efforts to contain the Bolshevik fleet based at Astrakhan. The first aircraft to arrive at Petrovsk (Makhachkala) on the western coast of the Caspian were DH9s and DH9As of 221 Squadron which commenced bombing missions against the railway systems at Kizlyar and Grozny early in February. In March, 221 Squadron was joined by 266 Squadron, equipped with various Short-built seaplanes, and both units began operations against Bolshevik shipping and military targets in the Volga delta. In May, 221 Squadron established a forward operating base at Chechen Island, which enabled the aircraft to reach as far as Astrakhan. On 20 and 22 May, 266 Squadron also attacked the Bolshevik naval base at Fort Alexandrovski on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea.

Over the summer of 1919 both northern and southern RAF detachments in Russia were significantly reinforced and a third front was opened in the eastern Baltic. In southern Russia, 47 Squadron plus a flight from 17 Squadron were dispatched to Beketovka, on the outskirts of Tsaritsyn (later Stalingrad) for operations north of the Caucasus. The squadron, which was equipped with DH9A bombers, commenced flying operations on 22 June and over the next months, their targets ranged from Bolshevik ground troops and railway rolling stock to barge traffic on the River Volga. Unlike northern Russia where there was no viable enemy air force, operations over the River Volga were challenged by Nieuport fighters flown by Bolshevik forces, which were based at Tcherni-Yar; in answer to this threat 47 Squadron received more Camels in September.

A naval force which included the aircraft carrier HMS Vindictive deployed to the eastern Baltic in July 1919. Operating from the Björkö Sound the force sought to contain Bolshevik naval forces in Petrograd. A number of raids were carried out by RN coastal motor boats, and also by the RAF air component embarked on HMS Vindictive, comprising Sopwith Camels and Short seaplanes. Most of the bombing attacks were against the naval installations at Kronstadt, which was attacked on an almost daily (and nightly) basis from July through until October. On some occasions, the aerial bombing was designed to distract the defenders while the motor boats attacked. Naval and aerial attacks were also carried out against the fortress at Krasnaya Gorka.

The RAF’s northern Russian detachments were reinforced by a number of volunteers in June 1919. Their arrival coincided with new aircraft being delivered which included the DH9, DH9A and the Sopwith Snipe as well as Fairey IIIC and Short 184 seaplanes. Daily sorties, lasting around 2 hours, were flown in support of White Russian ground forces by bombing enemy villages, railway junctions and strongpoints. Bolshevik naval craft operating on the lake were also attacked.

A Short Seaplane taking off from the River Dvina at Bereznik in late 1918 or early 1919, in support of White Russian forces fighting the Bolsheviks in northern Russia. From Bereznik, the aircraft could patrol over the river and rail approaches to Arkhangelsk from the southeast. Further to the west, seaplanes operating from Lake Onega and landplanes from Lumbushi covered the railway linking Moscow to Murmansk.

An Airco DH9A in northern Russia during 1919. Operating from Lumbushi on the northern tip of Lake Onega, these aircraft were flown by volunteers in support of the White Russian army fighting Bolshevik forces. (Jarrett)

A DH9 aircraft of 221 Squadron over Petrovsk during operations in early 1919 against Bolshevik forces in southern Russia. In the spring of 1919, working with the White Russian army, the aircraft bombed enemy forces and their transport infrastructure to the north of the Caucasus, reaching along the coast of the Caspian Sea as far as Astrakhan. (RAFM)

The Caspian Sea squadrons flew their last sorties in August and were then withdrawn. The RAF personnel in northern Russia were evacuated in October 1919 and HMS Vindictive and her air component also left the Baltic that month. That left only 47 Squadron, now renamed ‘A’ Detachment, in Russia: it continued to attack rivercraft and gunboats on the Volga between Astrakhan and Tsaritsyn, until it was also withdrawn in March 1920.

Sopwith Snipes of 70 Squadron. The unit was part of the occupation force based at Bickendorf in 1919. (Jarrett)

THE AFTERMATH OF WAR

Meanwhile the RAF, like the other services, had shrunk rapidly in the immediate aftermath of World War I. Of the 204 squadrons that existed in late 1918 only 29 remained by March 1920. A small number of flying units remained stretched across the Middle East and India, but the majority of flying squadrons had been reduced to cadre strength, or disbanded completely. Twenty squadrons had been deployed to Germany as part of the occupation force, mainly based at Bickendorf near Köln (Cologne); their role was largely restricted to flying mail runs and the last of the squadrons, 12 Squadron, was disbanded in 1922. As all three services reduced in size, both the Admiralty and the War Office fought to divide the RAF, and its budget, between them; it was only through adroit staff work and political patronage that the service survived these critical years. One unfortunate casualty of this political in-fighting was Major General Sykes, whose vision of an independent globally-positioned imperial air force proved to be too expensive for the post-war Treasury; he was replaced on 22 January 1919 Major General Trenchard, who had proposed a more affordable alternative. Ironically, during World War II, the RAF developed into an organization that closely resembled that of Sykes’ original vision. After taking over as Chief of the Air Staff (CAS), Trenchard proposed a future RAF comprising 32 flying squadrons, of which 18 would be based overseas to police the Empire; furthermore he wrote on 25 November 1919 that ‘it is intended to preserve the numbers of some of the great squadrons who have made names for themselves during the war, in permanent service units with definite identity, which will be the homes of the officers belonging to them, and will have the traditions of the war to look back upon.’ Thus was born the concept of squadron seniority which would underpin the traditions of the service over the next 100 years.

Although it arrived too late for wartime service, the four-engined Handley Page V/1500 was the first truly strategic bomber to enter RAF service and was capable of reaching Berlin from the UK. This particular aircraft, ‘Old Carthusian,’ had been flown from England to India in January 1919 and was used to bomb Kabul during the Third Afghan War of 1919. (Jarrett)

In April 1919, civil unrest erupted in India, which from the RAF’s perspective had been relatively quiet over the previous 12 months. At first, the two resident RAF units, 31 and 114 Squadrons were called to assist the army in dealing with civil disturbances, but at the beginning of May intelligence sources indicated that an invasion by Afghan troops was imminent. The squadrons, still equipped with the BE2c, a type that had long been withdrawn from front-line service elsewhere, were put on standby for operations. A reconnaissance flight by 31 Squadron reported the disposition of the Afghan troops, supported by local tribesmen, who crossed into India via the Khyber Pass on 6 May and occupied the settlement of Bagh. Three days later 16 aircraft carried out bombing attacks on the main Afghan encampment at Dakka while the Indian army carried out a counterattack at Bagh; although this action was unsuccessful, a second counterattack on 11 May drove the Afghans back across the border, hotly pursued by aircraft of 31 and 114 Squadrons and also the Indian army. The aircraft of 31 Squadron were also used to bomb Jalalabad. Meanwhile a Handley Page V/1500 bomber, which had been flown from the UK a few months earlier, was pressed into service. On 24 May, the aircraft was flown from Risalpur to bomb Kabul by Capt R. Halley DFC, AFC. Not only did his bombs cause damage to the palace of Amir Ammanulla, but they also had a significant personal and psychological effect on the Amir. Four days later, the Afghans counterattacked the British and Indian forces and laid siege to their camp at Thal. RAF aircraft played an important role in the relief of Thal on 1 June when they carried out bombing attacks against Afghan positions and directed the artillery fire from the relief force. The Third Afghan War ended in an armistice on 2 June.

On the same day plans were approved in London for the RAF to assist in quelling another insurrection in Somaliland, led by the ‘Mad Mullah,’ Mohammed bin Abdullah Hassan. In the past, such uprisings had been put down, at great cost, by large columns of ground troops, but Trenchard saw the opportunity to demonstrate that the RAF could carry out such work more cost effectively. The RAF contingent, known as ‘Z Unit,’ comprised just 12 DH9 bombers, plus their supporting personnel. After embarking on HMS Ark Royal, Z Unit arrived in Berbera on 30 December 1919 and was ready for action three weeks later from an airstrip at Eil dur Eilan (some 100 miles southeast of Berbera). The plan was for the aircraft to operate independently for four days and then co-operate with the Somaliland Field Force (SFF) comprising troops from the Camel Corps, the King’s African Rifles and local tribal levies; the Royal Navy would also provide support in coastal areas.

Operations in early 1920 to quell the insurrection in Somaliland led by the ‘Mad Mullah’ Mohammed bin Abdullah Hassan provided an opportunity for the RAF to demonstrate the concept of independent air control. One of the DH9 aircraft allocated to ‘Z’ Unit was modified to carry a stretcher, but during the campaign it proved to be more useful as a rudimentary transport aircraft. (Flintham)

Intelligence sources reported that Hassan was at the village of Medichi (Midhisho) some 100 miles northeast of Eil dur Eilan and between 21 and 24 January the aircraft carried out daily bombing raids against the village and the nearby fort at Jidali. However, during this time Hassan left the area to return to his main base at Taleh, so over the next five days, reconnaissance flights were made in an attempt to locate his party. The rebel forts at Jidali and Galibaribola were also bombed and both of these, as well as that at Badhan, were captured by the SFF. Meanwhile, a forward operating base was established at El Afweina, almost halfway between Medichi and Taleh: in this phase of the operation, a DH9 which had been converted to an ambulance proved particularly useful for transporting personnel and equipment to the new base. On the morning of 31 January, a reconnaissance flight located Hassan’s caravan and made an attack; the next day another pair of aircraft also bombed and strafed the party. Thereafter Hassan and his supporters managed to remain invisible to reconnaissance aircraft. The last offensive action by aircraft of Z Unit was to bomb Hassan’s palace and fortress complex at Taleh on 4 February. From that date, the aircraft were used exclusively for transport and communications, two roles which were essential in co-ordinating the widely-dispersed elements of the SFF. The Somaliland levies intercepted the main body of Hassan’s supporters on 5 February and captured the Taleh complex on 10 February, but Hassan had already slipped away. By 12 February 1920 it was clear that he had escaped to Italian Somaliland and was no longer a threat. The revolt had been put down effectively – at a cost of just four aircraft written off in accidents without casualties.

In India, the RAF had been reinforced by the arrival of three squadrons, 20 Squadron (Bristol F2b), 97 Squadron (DH10) and 99 Squadron (DH9A), in the summer of 1919. All of these units saw action when violence flared up in Waziristan in November. Rebel gangs from two major tribal groups, the Tochi Wazir and the Mahsud, objected to foreign rule and sought to overthrow the colonial administration in the tribal areas. The government response was to issue an ultimatum for all weapons to be surrendered to the authorities and a fine paid. The first ultimatum was issued to the Tochi Wazir and when this did not elicit any response, their villages were bombed. The bombing commenced in the morning and by mid-afternoon, the weapons had been handed in and the fine paid. The aircraft of 20 Squadron then dropped leaflets in the Mahsud areas. Once again there was no response, so the town of Kaniguram was bombed by 20, 97 and 99 Squadrons, but this time the bombing did not have immediate results. In fact, the Mahsud proved to be very reluctant to conform and a major army operation to restore order dragged on for the next three years. RAF aircraft played a significant part in these operations: the Bristol F2b aircraft of 20 and 31 Squadrons were used for co-operation with the ground troops, carrying out reconnaissance ahead of patrols. The squadrons also patrolled the areas around company-sized (picket) posts to advise if hostile parties approached, since the hilly terrain often provided excellent cover for any enemy advances. The bombers of 97 and 99 Squadrons attacked villages and also intercepted any potential reinforcements to Mahsud gangs. The bombing was carefully controlled so that it caused minimal damage: it was intended primarily as a show of force, but one that caused sufficient damage to keep the villagers too busy repairing their buildings and livestock shelters to support the insurrection.

The replacement of the Siddeley Puma engine in the DH9 by a 400hp Liberty engine produced the DH9A – the aeroplane which epitomized the RAF during the 1920s. Known in service as the ‘Nine-Ack’, the DH9A served with squadrons in the UK, Iraq, Palestine, Aden, Egypt and India. These aircraft are from 30 Squadron in Iraq during the late 1920s. (Pitchfork)

However, despite the theoretical strength of six squadrons in theatre, the RAF in India was actually in a parlous state. Although the RAF was supposedly an independent service, the Indian government merely regarded it as part of the Indian army and it had no separate budget. Perhaps not surprisingly the senior officers of the Indian army were not sympathetic to the requirements of the RAF, which was emasculated in India by a chronic lack of funds. This situation was further exacerbated by a rather bizarre moratorium from the Indian government on the import of any aircraft spares. Reporting in August 1922, Air Vice Marshal (AVM) Sir John Salmond wrote ‘it is with regret that I have to report that the Royal Air Force in India is to all intents and purposes non-existent as a fighting force.’

An Airco de Havilland DH10 Amiens bomber of 60 Squadron (re-numbered from 97 Squadron) in India. The aircraft saw action on the Northwest Frontier in late 1920 and early 1922. (Jarrett)

MESOPOTAMIA

In the summer of 1920, discontent at the British occupation of Iraq erupted into a violent rebellion by Arab nationalists in Baghdad. The British authorities lost control of a large swathe of the country, notably the regions around Karbala, Najaf and Samawah along the mid-reaches of the Euphrates. On 30 June, an army unit was besieged by a large force of Arabs in the centre of Rumaythah city; the Bristol F2b aircraft of 6 Squadron and RE8 aircraft of 30 Squadron played a vital role in supporting the beleaguered troops during three weeks of siege, mounting bombing sorties each day and also dropping supplies of food and ammunition. Indeed, the two squadrons were active across the whole area carrying out reconnaissance and taking offensive action, often in direct support of the forces on the ground. At the end of July, the situation had deteriorated sufficiently for there to be a major reinforcement of the army. At this stage 84 Squadron was formed at Baghdad, using DH9A aircraft which had originally been intended to re-equip 30 Squadron; additionally, 55 Squadron (equipped with Bristol F2b) was transferred to Iraq from Turkey later in the summer. Slowly the balance of power was restored: Kufah was retaken on 6 October by a military column which was supported by 6 Squadron and Samawah was relieved on 14 October, following an action which was heavily supported by air power. Najaf was subdued in early November, followed by Falujah and then Diwaniyah at the end of the month. In January the RAF mounted a show of force by flying a formation of 28 Bristol F2b aircraft over Baghdad. The revolt was formally considered to be over when Suq Al-Shuyukh capitulated on 3 February 1921.

PALESTINE

In Palestine, tensions between Palestinian Arabs and Jewish settlers had been building since the end of Ottoman rule. Inter-communal violence broke out at the beginning of May 1921 and martial law was proclaimed. On the morning of 5 May, a well-armed force of some 400 Arabs attacked the Jewish settlement of Petah Tiqva. A Bristol F2b from 14 Squadron was sent to disperse the attackers by flying low over them, until an Indian cavalry unit could intervene. Four bombs were dropped in front of the raiding party which caused them to withdraw, before they were dispersed by the cavalry. The next day, Arabs from the nearby village of Tulkarem were preparing to attack the Jewish settlement at Hadera. A Bristol F2b from 14 Squadron was able to prevent the attack for a while by dropping bombs and firing in front of the Arabs, but when the aircraft had to refuel, the raiders took advantage of the absence to start their attack. By the time the aircraft returned to Hadera the Arabs had infiltrated the southeast quarter of the settlement and were in the process of looting and burning the buildings, but the aircraft caused panic amongst the attackers who began to flee. At this point another aircraft and an armoured car arrived on the scene and the two aircraft, together with the armoured car, were able to ensure that the attackers were completely routed.

A Bristol F2b on the approach to land at Ramleh, Palestine. During civil disorder in the region in 1921, F2b aircraft of 14 Squadron prevented Arab insurgents from sacking the Jewish settlements of Petah Tiqva and Hadera. These incidents are credited with planting the idea of building an Israeli Air Force into the minds of the Yishuv leadership. (14 Squadron Association)

A Fairey IIID floatplane towed by a motor pinnace at Constantinople. The aircraft, which were normally based in Malta, were amongst the first arrivals to reinforce the beleaguered British force at Çanakkale in September 1922. (Jarrett)

THE DARDANELLES

At the end of World War I, Ottoman Turkey had been divided amongst the victorious Allies. The straits of the Dardanelles were declared a neutral zone and were administered jointly by Britain, France and Italy, while much of western Anatolia was granted to Greece. The immediate result of the latter edict of the Treaty of Sèvres was the Greco-Turkish War, which was fought from 1919 until the sacking of Smyrna (Ìzmir) by the Turkish forces in September 1922. The army of Kemal Ataturk then swung northwards towards the Dardanelles and the small British military contingent at Chanak (Çanakkale). French and Italian forces had withdrawn and the Turkish army seemed poised to overwhelm the British positions. Reinforcements were swiftly despatched, most particularly by the RAF; on 26 September Fairey IIID seaplanes arrived from Malta on HMS Pegasus followed the next day by 203 Squadron equipped with the Gloster Nightjar on HMS Argus. Both of these units were based at Kilya Bay, just across the straits from Çanakkale. On 30 September 1922, 56 Squadron equipped with the Sopwith Snipe and 208 Squadron with the Bristol F2b arrived from Egypt and were based at San Stefano (Yeşilköy) near Constantinople. On 11 October, 4 Squadron equipped with the Bristol F2b arrived having flown their aircraft off HMS Argus. This was the first occasion that any of the pilots had operated from an aircraft carrier, but nevertheless, all the aircraft made it safely to Kilya Bay. They were followed the next day by 25 Squadron equipped with the Sopwith Snipe and 207 Squadron flying the DH9A bomber which were delivered to San Stefano by HMS Ark Royal. By 10 October, the crisis was averted due to careful diplomacy, but the rapid arrival of the RAF (thanks to the RN) must have been a clear indication of the seriousness of the British resolve. Some units returned to their usual bases in the December, but most remained in Turkey until the summer of 1923.

A Sopwith Snipe 7F.1 of 25 Squadron flies over Constantinople (Istanbul) during the Chanak Crisis. The squadron remained in Turkey for a year before returning to the UK. The Snipe, which was originally intended as a replacement for the Sopwith Camel, continued to serve in Iraq with 1 Squadron until 1926. (Flintham)

Bristol F2b aircraft of 4 Squadron prior to flying off the deck of HMS Argus during the Chanak Crisis. The pilots had no previous experience of operating from the deck of an aircraft carrier. (Jarrett)

The RAF squadrons remained in Turkey through the harsh winter of 1922/23. Here the Bristol F2b Fighters of 4 Squadron are covered in snow at Kilitbahir (across the Dardenelles from Çanakkale). (Jarrett)

INDEPENDENT STILL

Despite the efforts of some in the Admiralty and the War Office, the RAF remained an independent service in the years immediately after World War I. The service might have become a shadow of its former wartime self, but it was still active, albeit thinly stretched, across the Empire and in its short existence had demonstrated the effectiveness of air power both in the environment of total warfare and also the role of colonial policing.