CHAPTER 4

THE ROAD TO VICTORY

1943 - 1945

Pilots brief for a sortie in front of a rocket-armed Hawker Typhoon Mk IB at a forward operating base in Northern France during the summer of 1944. Fitted with a 60lb warhead, the 3-inch RP-3 Rocket Projectile (RP) carried by the Typhoon was very effective against German armour. (Getty/PNA Rota)

At the beginning of 1943 the RAF was engaged in four major theatres of operations: the Far East, the Middle East, the Atlantic and Europe. Newer aeroplanes, including many US-built types were replacing the obsolescent and generally unsuitable aircraft with which RAF crews had been equipped during the first years of the war. Modernization was coupled to a massive expansion of the service, including flying training schools which provided a growing stream of well-trained aircrews. In the Middle East, the corner had been turned and victory seemed at last to be a distant possibility; the balance of operational fortune would shortly swing in favour of the Allies in the other theatres, too.

NORTH AFRICA

In Egypt, the 8th Army finally broke out from El Alamein in November 1942 and the Afrika Korps retreated rapidly back towards Tunisia. Unfortunately, despite having air superiority over the area, the Desert Air Force was unable to capitalize on the German withdrawal and the Afrika Korps was able to regroup in defensive positions at the Mareth Line. From mid-March until the final surrender of Axis forces in North Africa the aircraft of the Western Desert Air Force worked closely with land forces. Boston and Maryland bombers carried out softening-up attacks on the enemy frontline and on communications and transport in the rear echelons; meanwhile Kittyhawks and Hurricanes sought out artillery and armour. Spitfires ensured that Allied aircraft enjoyed air superiority over the region and the medium bombers also systematically attacked the enemy-held airfields in northeastern Tunisia. The Axis forces were also cut off from their supply lines by Beauforts, Beaufighters and Wellingtons operating from Malta against shipping convoys, as well as Wellingtons which bombed the Tunisian ports. In April, the Luftwaffe attempted to carry out resupply and evacuation by air, but between 5 and 22 April over 400 Luftwaffe transport aircraft, including Junkers Ju52 and six-engined Messerschmitt 323 transports were shot down by allied fighters. A total of 24 Junkers Ju52 aircraft were accounted for on 10 April and on 18 April a total of 53 Ju52 transports were shot down. The remaining Axis forces in Tunisia capitulated on 13 May.

The ubiquitous Vickers Wellington provided the RAF in the Middle East with a long-range bombing capability. Aircraft from 37 Squadron take off from Shallufa in the Canal Zone. (Flintham)

Ground operations over long ranges in the inhospitable terrain and difficult climate of Burma were only possible thanks to air transport. The workhorse of the RAF transport squadrons in the Far East was the Douglas C-47 (DC-3) Dakota, here in service with 31 Squadron. (Flintham)

ARAKAN

The monsoon season of the second half of 1942 precluded any further action over Burma, but it also gave the RAF squadrons in India breathing space to re-arm. Small-scale Japanese night-time bombing raids on Calcutta in December 1942 caused a disproportionate panic in the city, but the introduction of four radar-equipped Beaufighter night fighters soon restored the balance; this unit expanded to become 176 Squadron. An army offensive into the Arakan region started on 27 December 1942. The Bristol Blenheim V of 11, 42 and 113 Squadrons, the Blenheims of 60 Squadron and the Vultee Vengeances of 110 Squadron, escorted and supplemented by Hurricanes from 67, 79, 135, 136, 146 and 607 Squadrons attacked targets ahead of the ground troops to clear their way. In February 1943, the offensive was expanded to include the first expedition by the ‘Chindits’ (Long Range Penetration Groups). During their Operation Longcloth, the Chindits were supplied by air by the Douglas DC2s and DC-3 Dakotas of 31 Squadron. These aircraft were also involved in the Allied airlift to supply Chinese Nationalist forces, flying over the eastern Himalayas (the ‘Hump’). The 31 Squadron aircraft carried out weekly flights to China from Dinjan, where they were protected by the Curtiss Mohawks of 5 Squadron. Operation Longcloth ended in April and the Arakan offensive ended in a withdrawal by British and Indian forces in May 1943, before the start of the next monsoon season.

Vultee Vengeance dive bombers of 84 Squadron. Equipping four RAF and two Indian Air Force (IAF) squadrons, the Vengeance was ideally suited to ground-attack operations over Burma. (RAFM)

Although ground operations were curtailed by the monsoon, limited air operations continued and in particular the garrison at Fort Hertz, which was behind enemy lines in northeastern Burma, was kept resupplied by air.

The summer monsoon season in the Far East provided an opportunity for the RAF units in the theatre to re-equip with more modern aircraft. In particular, the Spitfires of 81, 136, 152, 607 and 615 Squadrons enabled the RAF to take the initiative in the air and establish air superiority over the Japanese air force. The Blenheims of 11, 34, 42, 60 and 113 Squadrons were replaced by Hurricane fighter-bombers, which were far more suitable for close air support of troops than the previous type. The Vengeance dive bombers of 45, 82, 84 and 110 Squadrons and Beaufighters of 27 and 177 Squadrons also swiftly proved their effectiveness against Japanese lines of communication in the rear areas. Perhaps the most important development in a theatre where movement over long distances was hampered by steep terrain and thick jungle was the expansion of the transport fleet: Dakotas of 62, 194 and later 117 Squadrons joined those of 31 Squadron, making large-scale air movement of troops and supplies a reality. During the course of 1943 the weekly task of an air transport squadron had increased sevenfold.

A Boeing B-17 For tress IIA of 220 Squadron flies past the Hebrides in May 1943. Some 200 of these aircraft were operated by Coastal Command, mounting anti-submarine patrols into the mid-Atlantic from Chivenor, Benbecula, Iceland and the Azores. (RAF Official Photographer/IWM/Getty)

U-BOATS & COASTAL SHIPPING

The campaign against U-boats in the Atlantic and the Bay of Biscay intensified through the first half of 1943. The Bay of Biscay became a battleground between Coastal Command’s aircraft and German submarines and aircraft. Equipped with the more capable ASV III and IV radars, Sunderlands, Catalinas, Whitleys, Wellingtons and Hampdens were successful in forcing U-boats to remain submerged during daylight. These patrols were particularly effective because they were focussed on the routes known to be used by U-boats while transiting from their bases in northern France. At night, the patrols were continued by Leigh Light-equipped Wellingtons of 172 Squadron (later joined by 407 and 612 Squadrons). In March 1943, a total of 52 U-boats were detected in the Bay of Biscay and just over 50 percent were attacked, with one confirmed kill; the following month aircraft found almost 100 submarines and attacked 64, sinking seven. The Luftwaffe contested the air over the Bay of Biscay with Ju88 and Focke-Wulf Fw190 fighters, but these were countered by fighter sweeps by Beaufighters of 143, 248 and 235 Squadrons.

By May 1943 there were five squadrons of Very Long Range (VLR) Liberators (53, 59, 86, 120 and 224 Squadrons) which were able to cover the convoy routes in the mid-Atlantic, while closer to land the convoys were escorted by Sunderland, Catalina, Halifax and Fortress aircraft. The response from Admiral Dönitz was to order the U-boats to operate using Rudeltaktik (pack attack by animals) tactics known as ‘Wolfpacks’ and to attack at night when the air cover had departed, for the longer-range aircraft still had no night capability. Even so, the combined efforts of the convoy escort and anti-submarine aircraft working together was taking a relentless toll on the U-boat force. A total of 41 U-boats were sunk in the month of May 1943, which is often regarded as the turning point in the ‘Battle of the Atlantic.’

Anti-submarine aircraft also operated from Gibraltar: Hudsons of 48 and 223 Squadrons and Catalinas of 292 Squadron carried out daylight patrols while the Leigh Light-equipped Wellingtons of 179 Squadron operated at night. These aircraft could cover the eastern Atlantic from the Iberian coast and also the western Mediterranean.

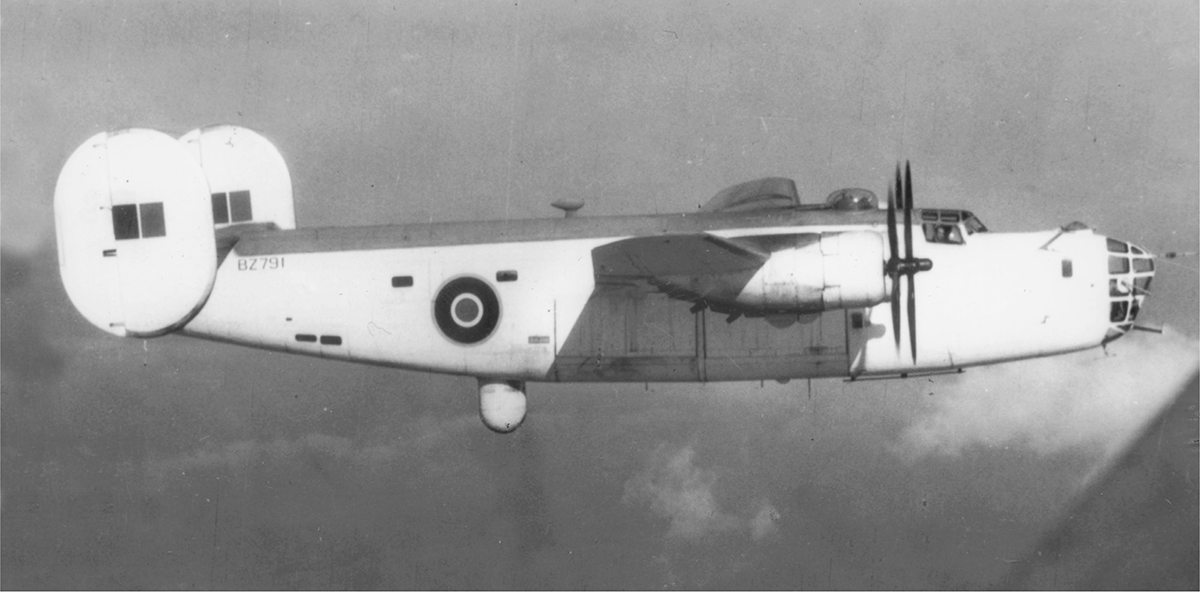

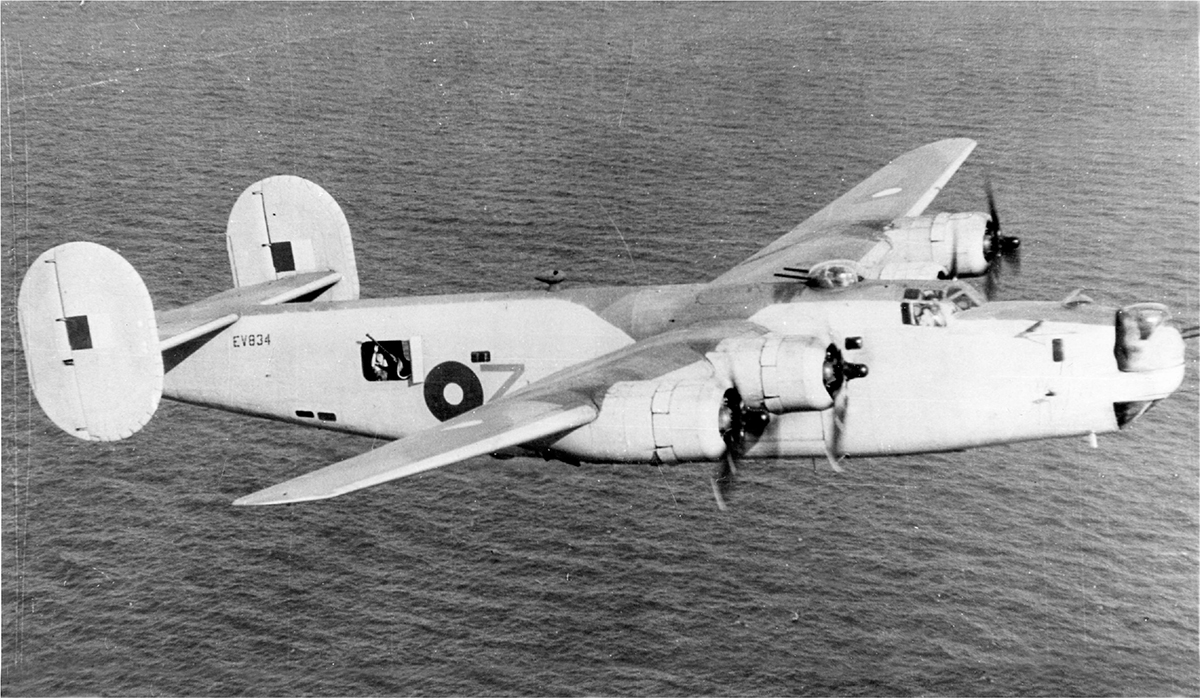

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator was one of the most important aircraft to be operated by the RAF during World War II. In the role of the Very Long Range (VLR) aircraft, the Liberator enabled the RAF to close the ‘Mid-Atlantic Gap’ in air cover for convoys, thus playing a vital role in the winning of the Battle of the Atlantic. This example is a Liberator GR V with an ASV radar mounted in a ventral housing. (RAFM)

Almost from the start of the war, aircraft from both Coastal and Bomber Commands had routinely attacked German shipping off the coasts of northern Europe and Norway. However, the Hudsons, Hampdens and Blenheims were particularly unsuitable for such operations and in the three years between April 1940 and March 1943, 107 ships had been sunk at a cost of 648 aircraft lost. In contrast in the same period, dropping of mines in coastal areas, which was seen at Command-level as being a low-priority task, accounted for 369 ships, for 329 aircraft lost. The introduction of the high performance Beaufighter offered a more effective aeroplane with which to carry out anti-shipping strikes and a Strike Wing of three Beaufighter squadrons (143, 236 and 254 Squadrons) was established at North Coates in late 1942. The Wing’s first operation in November 1942 did not go well, but after further training another operation was mounted on 18 April 1943. This operation by 21 Beaufighters escorted by Spitfires and North American P-51 Mustangs was successful and marked the start of sustained Beaufighter anti-shipping operations.

By early 1943, the Avro Lancaster was equipping an increasing number of squadrons within the Bomber Command heavy bomber force. This is a Lancaster B I operated by 50 Squadron which was based at Swinderby, Lincolnshire in 1942. (Hulton Archive/Getty)

THE BOMBING CAMPAIGN

Just as effective anti-shipping operations became a reality with the introduction of the Beaufighter in Coastal Command, so the arrival of the de Havilland Mosquito in Bomber Command had enabled the RAF to carry out precision bombing attacks. On 27 January 1943, a force of nine Mosquitoes from 105 and 139 Squadrons took part in a low-level daylight raid on the Burmeister and Wain submarine engine factory in Copenhagen. This was followed three days later by two raids, each by three aircraft from the same squadrons, on Berlin. These latter attacks successfully disrupted the celebrations of the tenth anniversary of the Nazis’ rise to power. A third similar raid was carried out by ten Mosquitoes of 139 Squadron against the molybdenum mine at Knaben in Norway. Over the next few months these two squadrons carried out daylight attacks on railway marshalling yards at Nantes, Tours and Trier. A less successful raid was an attack on the power station at Amsterdam on 3 May 1943 in which all 11 of the attacking force of Lockheed Venturas from 487 Squadron RNZAF were shot down.

The high performance of the Mosquito B IV gave Bomber Command the capability to attack targets with greater accuracy than could be achieved by a heavy bomber or the previous generation of medium bomber aircraft. (Popperfoto/Getty)

At the Casablanca conference in January 1943, the RAF was charged with the general destruction of German industry by night, while the bombers of the 8th Air Force (USAAF) concentrated on more specific industrial targets. By then Bomber Command had expanded to over 50 squadrons, 35 of which were equipped with ‘heavy’ types such as Stirling, Halifax and Lancaster bombers, many of which were equipped with the Gee navigation system. Another radio-based precision navigation system, ‘Oboe’, which was fitted to the Mosquitoes of 105 Squadron, enabled the PFF to perfect its techniques for target marking. Later both 109 and 139 Squadrons were also equipped with Oboe and transferred into the PFF. A campaign against the industrial area of the Ruhr valley, using the new target marking techniques, started with an attack on Essen on 5 March. The initial markers, comprising eight Oboe-equipped Mosquitoes, dropped yellow Target Indicator (TI) flares at 15 miles to run to the target and red markers on the aiming point in the centre of the Krupp industrial complex in Essen; they were followed by 22 ‘backers up’ which dropped green TIs as well as incendiaries onto the red markers. Three waves, each made up of a different bomber type, then followed: firstly Halifaxes, then a mix of Stirlings and Wellingtons and then finally, Lancasters. In all, 367 aircraft attacked the target with encouraging results. Essen was bombed the following week and again on 3 and 30 April. Similar attacks were carried out on other industrial cities in the Ruhr area: Duisburg was bombed five times, including large attacks on 26 April and 12 May, Düsseldorf was bombed on 25 May and 11 June and Wuppertal on 29 May.

Amongst these area attacks, in a remarkable feat of airmanship, 19 Lancasters of 617 Squadron carried out a night time low-level precision attack on three dams in the Ruhr valley on 16 May. Two of the dams were breached, but the critical Sorpe dam was undamaged and eight of the aircraft were lost; however, perhaps the most important legacy of the raid was the concept pioneered by Wg Cdr G.P. Gibson DSO* DFC* of a ‘Master Bomber’ controlling each individual attack by VHF radio to ensure its accuracy. Ten days later another remarkable daylight raid was carried out by 14 Mosquitoes of 105 and 139 Squadrons which successfully bombed the Carl Zeiss optical systems factory at Jena near Leipzig.

Trolleys loaded with 250lb bombs are prepared for loading into a Douglas Boston of 88 Squadron. The type served with four bomber squadrons in Bomber Command as well as three night intruder squadrons and a further four bomber squadrons with the Desert Air Force in Italy. (Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty)

SICILY, ITALY & THE BALKANS

In the last days of the North African campaign, Allied aircraft had already started softening up targets in Sicily and Italy. USAAF bombers and the Wellingtons of 37, 40, 70, 104, 142 and 150 Squadrons bombed industrial targets around Naples and Bari as well as airfields in Sicily, Sardinia and southern Italy and the lines of communication around Palermo and Catania. The garrison at Pantelleria Island was subjected to a short but effective bombardment between 7 and 11 June and both Pantelleria and Lampedusa were taken by Allied forces on 12 June. Meanwhile Airspeed Horsa and US-built Waco Hadrian gliders had been towed from UK to North Africa by Halifaxes and Armstrong-Whitworth Albermarles of 295 and 296 Squadrons. These were used on the evening of 10 July to land airborne troops on Sicily prior to the main seaborne invasion the following day. Seven Halifaxes of 295 Squadron and 27 Albermarles of 295 and 296 Squadrons were involved in the operation. Meanwhile Wellingtons bombed targets near Syracuse, Caltagirone and Catania and the Hurricanes of 73 Squadron attacked enemy searchlight units. The main landings were covered by Spitfires during the day and Beaufighters of 108 Squadron at night time, while night intruder Mosquitoes of 23 Squadron operated against German and Italian airfields. On 13 July, the Spitfires of 1 (SAAF), 92, 145, 417 (RCAF) and 601 Squadrons started to operate from a forward base at Comiso and that evening Albermarles and Halifaxes towed 17 gliders to assault the bridge at Primosole near Catania. Throughout the campaign in Sicily, the Wellingtons assigned to the Northwest African Strategic Air Force bombed targets in Italy including railway marshalling yards at Salerno, Naples and Foggia, while the torpedo-armed Wellingtons of 36 Squadron, operating in loose formations of three aircraft, patrolled the seas each night, hunting for Axis shipping. The attentions of these aircraft, as well as Beauforts and Beaufighters operating from Malta had effectively shut down German and Italian coastal shipping in the region. Bomber Command aircraft also carried out raids against Milan, Genoa and Turin during the first 14 days of August. The Germans evacuated Sicily on 17 August 1943. Following the fall of Sicily, Mussolini was overthrown and the Italians negotiated an armistice, which was announced on 8 September. At dawn the following day, Allied troops landed at Salerno. The landings were covered by Allied aircraft including Spitfires based in Sicily; over the next few days the Luftwaffe attempted to intervene, but Allied aircraft had established air superiority over the landings and 221 German aircraft were shot down. The Luftwaffe was subsequently limited to operating at night time. Allied bombers continued operations against the transport infrastructure in the rear areas and fighter-bombers sought targets of opportunity immediately behind the frontlines.

A Liberator of 108 Squadron delivering supplies to partisan forces in Yugoslavia. Such missions, involving low-level drops in mountainous terrain, were extremely hazardous.

The surrender of Italian forces left a vacuum in the Greek islands garrisoned by Italian troops and both British and German forces moved to seize possession. The Germans were able to secure Rhodes quickly, but the Special Boat Service (SBS) landed on Kos on 13 September and paratroops were dropped on the island by Dakotas of 216 Squadron the following day. The Luftwaffe in the Aegean and Balkans was strongly reinforced over the next week. Kos was attacked by German aircraft on 17 September, but the raiders were met by stiff resistance from by 2901 and 2909 Squadrons of the RAF Regiment, which had deployed from Palestine to provide air defence of the island. Meanwhile, German airfields around Athens were attacked by Liberator, Halifax, Wellington and Hudson bombers. Unfortunately, Kos did not remain in British hands for long: the Germans successfully captured the island on 3 October 1943.

Allied troops had taken much of southern Italy and by 1 October Naples was in Allied hands and the Germans had evacuated Sardinia. During the advance from the Salerno beachhead, a system for close air support of troops known as ‘Rover David’ had been established. This technique involved a radio-equipped Forward Air Controller (FAC) directing fighter-bombers, waiting in a ‘cab rank’ above the battlefield, onto targets close to friendly forces on the frontline. By the autumn the frontlines had become static, with the Germans established on the defensive Gustav Line, which ran from roughly 30 miles north of Naples on the west coast to roughly 30 miles south of Pescara on the east coast.

Liberators of 108 Squadron had started dropping supplies to partisans in Yugoslavia in May 1942. Their work had been taken up by 148 Squadron, which had been formed for special duties with Liberators and Halifaxes. With Allied aircraft now able to operate from southern Italy more direct support of the partisans was possible and on 24 October, Kittyhawks from 112, 250, 260 and 450 (RAAF) Squadrons attacked German ships landing troops near Dubrovnik. Aircraft from the Mediterranean Allied Tactical and Coastal Air Forces (MATAF and MACAF) were also tasked against shipping, storage facilities, radio stations, oil storage, bridges and gun emplacements along the Adriatic coast.

Spitfire VC and IX aircraft of 232 Squadron at an advanced landing ground at Serratelle near Salerno in October 1943; these aircraft had covered the amphibious landings at Salerno the previous month. (Fg Off L.H. Abbott/IWM/Getty)

THE BOMBING CAMPAIGN CONTINUES

Bomber Command’s strategic aim was modified slightly in mid-1943 to destroy the German aircraft industry rather than general industry, so the targets were chosen from amongst those cities which contained factories associated with the manufacture of aircraft parts. On 20 June, 60 Lancasters, including those from 9, 50, 97, 408 and 467 Squadrons, attacked the Zeppelin factory at Friedrichshafen, using the Master Bomber technique. After the attack, the aircraft continued to Blida, Algeria. Three days later they flew back to the UK, bombing the Italian naval base at La Spezia on the return leg. Raids against industrial cities in the Ruhr continued, but a series of attacks on Hamburg commenced on 24 July. The city was out of range of the Gee and Oboe networks, but its location near the coast on the River Elbe meant that it could be located easily using the new H2S mapping radars which were fitted to many of the bombers. Hamburg was visited on the nights of 24, 27 and 29 July by a force of about 740 aircraft which delivered around 2,400 tons of bombs on each occasion. These raids were the first to use ‘Window,’ made up of strips of aluminium foil, to disrupt German air defence radars. USAAF bombers also attacked during the daylight hours of 25 July and the final raid was made by a smaller force of Lancasters on the night of 2 July. Although massive damage was done to the urban areas, industrial production was restored relatively quickly.

A Vickers Warwick I of 269 Squadron carrying a lifeboat under the fuselage. Some 350 of these aircraft, which was originally designed as a replacement for the Wellington, were used instead for Air Sea Rescue (ASR) operations. (Flintham)

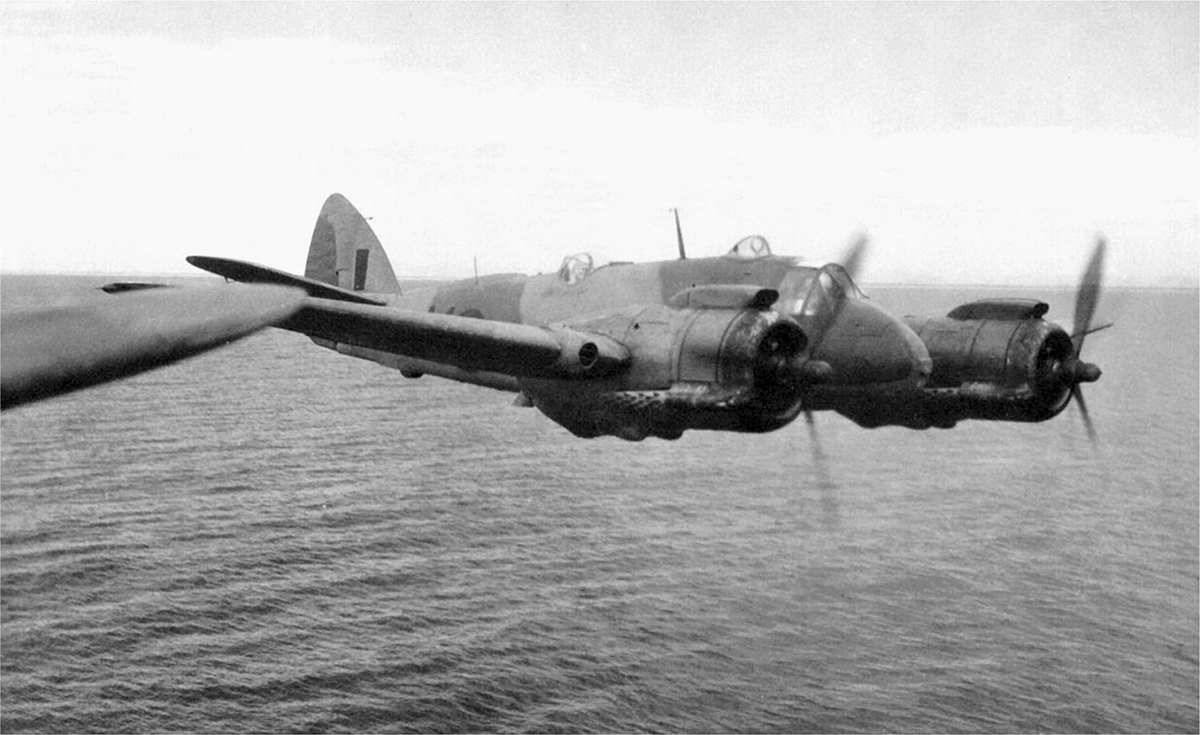

A Bristol Beaufighter X of 455 Squadron fires a salvo of RP-3 Rocket Projectiles. The Strike Wings in Coastal Command were very effective against German coastal shipping by using a mixture of torpedo and rocket-armed aircraft. (Pitchfork)

Nightly attacks continued through the next months, including bombing the research station at Peenemünde on 17 August and further raids on Berlin, Mannheim, Hanover, Kassel and Düsseldorf. An attack on Düsseldorf on 3 November was the operational debut of another electronic navigation aid, ‘G-H,’ which incorporated a transponder on the aircraft. Other electronic equipment was also used to help to protect the bomber crews: these included the Bolton-Paul Defiants of 515 Squadron using ‘Moonshine,’ and later ‘Mandrel’ to confuse and jam German early warning radars. Meanwhile, the Beaufighters (and later, Mosquitoes) of 141 Squadron equipped with ‘Serrate,’ which homed onto air-intercept radar signals, accompanied the bomber stream and operated against Luftwaffe night fighters.

A High Speed Launch (HSL) Type 3; a total of 69 were built and used by the Air Sea Rescue service from late 1942. Powered by three 500hp Napier Sea Lion petrol engines, the 68ft vessel was capable of up to 28kt. (Charles E. Brown/RAF Museum/Getty)

COASTAL COMMAND

The pressure on U-boats both in the Bay of Biscay and the Atlantic continued through the second half of 1943. A second Leigh Light-equipped Wellington squadron, 304 Squadron, increased Coastal Command’s night anti-submarine capability over the Bay of Biscay. During August a total of 56 U-boats were sunk by combined naval and air forces in the Atlantic and in October, 20 U-boats which were operating within range of aircraft based in Iceland were sunk in a 14-day period.

In north European coastal waters the anti-shipping Strike Wing at North Coates was proving to be very effective. A typical strike would comprise 12 torpedo-armed Beaufighters escorted by 16 defence suppression Beaufighters, armed with Rocket Projectiles (RPs) and cannon. A second wing was formed at Leuchars in early 1944 with 455 (RAF) and 489 (RNZAF) Squadron Beaufighters.

The PRU continued with its reconnaissance of enemy-held Europe: camera-equipped Spitfires flying at 42,000ft ranged as far as Gdinya, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest and Belgrade, sometimes landing in Italy or North Africa to refuel before returning to base. Coastal Command’s Air Sea Rescue force had also expanded to include Supermarine Walrus flying boats (of 276, 277, 278, 281 and 282 Squadrons) as well as Hudsons (of 279 and 280 Squadrons) equipped with air-droppable lifeboats. Another vital task carried out by Coastal Command was that of meteorological (‘Met’) reconnaissance. Initially these were carried out by independent Met Flights, but by late 1943 the units had been expanded to squadron strength: 517, 518, 519, 520 and 520 Squadrons operated Halifaxes and Fortresses flying daily Met sorties into the Atlantic to obtain observations of winds and temperatures. On occasions, during the course of their observations the aircraft were also involved in combat against both enemy aircraft and submarines.

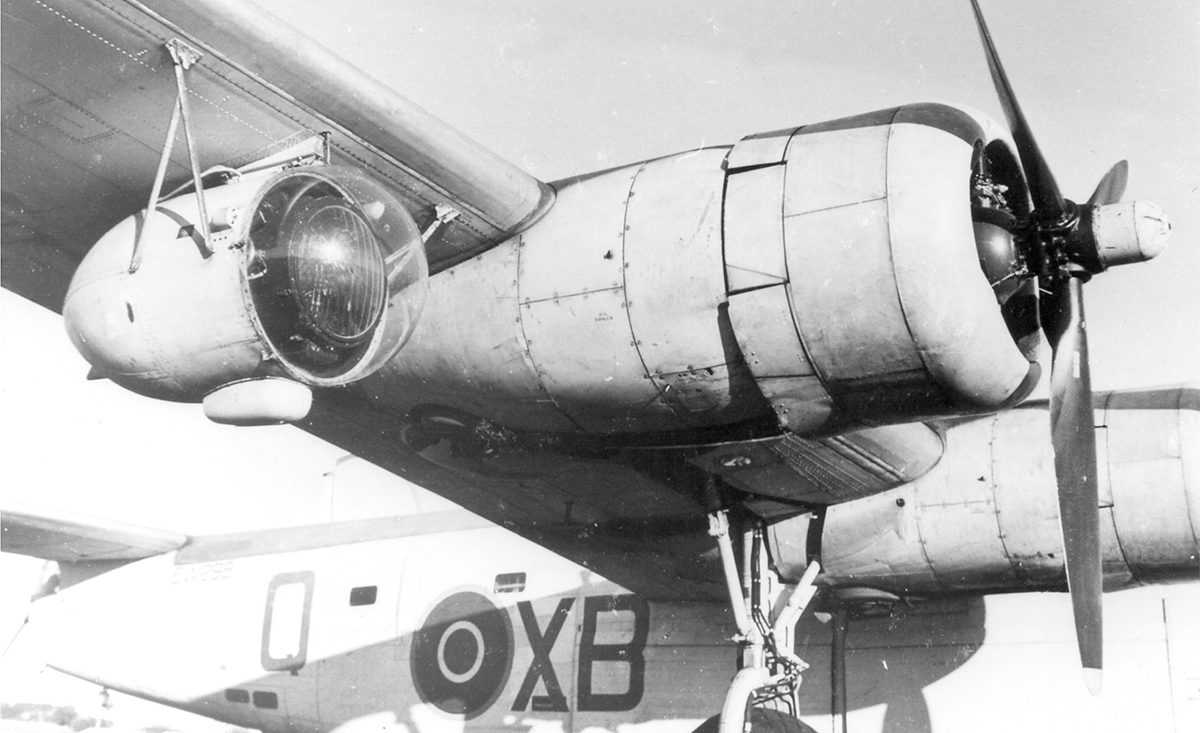

A Leigh Light mounted under the wing of a Liberator GR VI of 224 Squadron. In early 1944, the unit was based at Milltown, on the Moray Firth, Scotland to counter U-boats operating from bases in Denmark and Norway. (Pitchfork)

By January 1944, U-boats had abandoned operations as large packs and had instead opted to act individually or in small groups. Most of their activity took place at night time off the west coasts of Ireland and Scotland, so Leigh Light patrols were switched from the Bay of Biscay to this area. However, a continuous 24-hour patrol line was set up blocking access into the English Channel from the west so that U-boats could not interfere with the forthcoming landings in Normandy.

A Supermarine Walrus II amphibian picks up a pilot from his dinghy. Seven squadrons operated this type in the ASR role and many aircrew owed their lives to the bravery of the Walrus crews. (Keystone/Getty)

PREPARATIONS FOR D-DAY

A bombing campaign against Berlin started on 18 November 1943. On that night 402 aircraft attacked the city and over the next four months 16 major raids were mounted against Berlin. The heaviest of these was on 15 February 1944, when 561 Lancasters, 314 Halifaxes and 16 Mosquitoes delivered over 2,600 tons of bombs, but they did so at a significant loss rate of over 6 percent. Well beyond the range of Gee, Oboe and G-H, Berlin was also difficult to detect using H2S radar. Navigators were therefore forced to rely on the technique of dead reckoning, but aircraft such as Lancasters, with much better performance than their predecessors, flew at altitudes that were affected by jet stream winds, phenomena which were little understood at the time. As a result of these factors, navigation during the ‘Battle of Berlin’ was challenging and bombing accuracy suffered accordingly. On the last raid which took place on 24 March the markers were blown off the target area by the winds and very little damage was done by the 811 aircraft which were tasked for the mission. The loss rate of heavy bombers at this time was typically about 4 percent, but on some missions, it was much higher: the 44 Lancasters and 34 Halifaxes shot down on the raid on Leipzig on 19 February represented over 9 percent of the 823 attacking aircraft.

On the night of 8 February 1944, a force of 12 Lancasters from 617 Squadron bombed the Gnome et Rhône aircraft engine factory at Limoges. With no target defences and with the benefit of bright moonlight, the formation leader, Wg Cdr G.L. Cheshire DSO** DFC was able to mark the target exactly from low level and the subsequent attack was extremely accurate. A number of daylight precision raids were also carried out by Mosquitoes in early 1944. On 18 February, the wall at Amiens prison was breached by Mosquitoes from 21, 464 (RAAF) and 487 (RNZAF) Squadrons which were escorted by Typhoons of 174 and 198 Squadrons and on 11 March the Gestapo headquarters building in The Hague was bombed by six Mosquitoes from 613 Squadron.

A Hawker Typhoon Mk 1B of 175 Squadron being loaded with 250lb bombs in preparation for a mission over northern France. Using a combination of cannon, bombs and rockets, the Typhoon squadrons of the 2nd Tactical Air Force attacked German armour, vehicles and trains in the run-up to D-Day; subsequently the type provided close air support for Allied troops during the Normandy campaign. (Fox Photos/Getty)

From March, Bomber Command’s heavy bombers were included in the ‘Transportation Plan,’ which involved the destruction of the transport infrastructure in northern France so that the German army would find it difficult to redeploy or reinforce when Allied forces landed in France later in the year. Targets included the marshalling yards at Trappes, in the western suburbs of Paris, which was bombed by on 6 March, and these missions incurred significantly fewer losses than raids on Germany. Nevertheless, large-scale raids continued against German cities. Stuttgart was attacked on 1 and 15 March, Frankfurt on 18 and 22 March, Essen on 26 March and Nuremberg on 30 March. On this last raid, about 120 of the 795-strong attack force mistakenly bombed Schweinfurt some 50 miles away and there was minimal damage to Nuremberg itself.

In May, as part of the ‘Transportation Plan,’ bridges in northern France were also targeted, but the lessons of previous operations against bridges had been learnt: a careful analysis of these operations indicated that rocket-firing Typhoons and bomb-dropping Spitfires were best suited against these targets. The Typhoons and Spitfires also targeted railway locomotives and rolling stock and, along with the heavy bombers, they also began attacks in early May on German coastal radar installations and naval fire control sites. In order not to give away the location of the beaches selected for amphibious landings, two ‘out of area’ targets were attacked for every target that was in the invasion area. On 2 June 1944, Typhoons of 198 and 609 Squadrons attacked targets near Dieppe, followed by a night attack by heavy bombers in the same area. Two days later Spitfires of 441, 442 and 443 (RCAF) Squadrons bombed Cap d’Antifer and the heavy bombers attacked sites near Cherbourg; on 5 June, Typhoons of 174, 175 and 245 Squadrons attacked Cap de la Hague.

A rare image of a Hawker Hurricane IIB of 258 Squadron over Arakan, Burma in 1943. During the battles of Imphal and Kohima, Hurricane squadrons operated from airstrips within the Imphal perimeter to provide close air support to the ground forces.

ADEN

The Gulf of Aden, at the mouth of the Red Sea, was a choke point for shipping transiting to and from the Suez Canal. In 1944, the Wellingtons of 8 and 621 Squadrons provided anti-submarine cover for shipping sailing through the region. However, the issues of pre-war colonial policing never fully disappeared and in early 1944, the colonial government in Aden was faced with a famine in the Wadi Hadramaut. Six Wellingtons flew food supplies to the airstrip at Al Qatn on 29 April, starting a month-long airlift to deliver over eight tons of milk and 400 tons of grain into the Hadramaut. During this operation, the anti-submarine patrols continued and on 2 May a Wellington from 621 Squadron located the U-boat U-852 off the coast of Somalia. The submarine was then neutralized by depth-charge attacks by aircraft from both squadrons.

A Handley Page Halifax II Series I Special in the Middle East. This version of the aircraft had the original high-drag nose turret replaced with a fairing. The type was used in the Mediterranean and Balkans both as a heavy bomber (shown) and also as a special duties aircraft; in the latter role the type was used in support of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). (Flintham)

RETURN TO ARAKAN

In late 1943 and early 1944, the RAF swiftly established air superiority over northeast India, Burma and the Bay of Bengal. A force of 12 Japanese aircraft which attempted to attack shipping off the Arakan coast were shot down by Spitfires of 136 Squadron on 31 December 1943. On 4 February 1944, XV Corps commenced the second offensive into the Arakan. Many of the front-line troops were supplied by Dakotas from 62 Squadron, whose aircraft each flew three sorties a day. Wellingtons bombed enemy airfields at night and, along with Liberators of 160 Squadron, they also attacked railway marshalling yards as far away as Bangkok and Moulmein.

After reaching Maungdaw, the XV Corps advance was halted by a Japanese counterattack and by 10 February the British, Indian and African troops found themselves surrounded by the Japanese army. The Japanese were held off by troops in the administrative echelon of 7th (Indian) Division, in a defensive position known as the ‘Admin Box.’ Completely cut off by Japanese forces, the Admin Box was resupplied by RAF Dakotas and USAAF Curtiss C-46 Commandos, which were able to operate freely thanks to the RAF’s command of the air over Burma. In the period between 8 February and 6 March 1944, 2,000 tons of supplies were delivered to troops in the Admin Box. Meanwhile Vengeances and Hurricanes continued their attacks on Japanese positions. The siege was broken on 22 February and the Arakan offensive continued for a short while before being curtailed so that the forces at Imphal and Kohima could be supported.

A second Chindit expedition, Operation Thursday, commenced on the night of 5 March 1944 when a force of over 9,000 troops was transported by air into jungle landing strips behind Japanese lines by Dakotas of 31, 62, 117, and 194 Squadrons. Over the next four months, these troops were supplied entirely by RAF Dakotas, and the C-46 Commando and Douglas C-47 Skytrain transports of the USAAF Air Commando. Many casualties were evacuated from the jungle by light aircraft, but Sunderlands of 230 Squadron also flew evacuation missions from Lake Indawgyi in northern Burma.

A major Japanese offensive had also started in early March 1944. Japanese forces crossed the River Chindwin and began to advance into India on 8 March, but they were stopped at Imphal and Kohima. However, in halting the Japanese advance, the British and Dominion forces at Imphal found themselves cut off from their usual resupply and reinforcement routes and for 80 days Imphal was kept supplied by air. The 5th (Indian) Division was also air-lifted from Arakan to the central front to the north of Imphal by Dakotas of 194 Squadron and C-46 Commandos of the USAAF. A total of 11 Hurricane-equipped squadrons and four Vengeance-equipped squadrons, initially operating from six airstrips within the Imphal perimeter, flew close air support missions against Japanese forces. Further north, Hurricanes flew some 2,200 sorties in support of the defenders of Kohima between 4 and 20 April and over the same period Vengeance dive bombers also provided direct support as well as attacking Japanese encampments and supply dumps. The Spitfires of 81, 136, 152, 607 and 615 Squadrons ensured that the Imperial Japanese Air Force could not intervene in the battle. Meanwhile Beaufighters and Hurricanes interdicted and interrupted the Japanese supply lines. Intense fighting, some of it at close quarters, continued at Kohima and Imphal through the next months into June.

A Bristol Beaufighter X of 217 Squadron, operating over the Bay of Bengal from Ratmalana, Ceylon in the summer of 1944. During the previous year, RAF Beaufighters carried out a successful long-range interdiction campaign against the Japanese lines of communication in Burma. (Pitchfork)

ITALY

A second amphibious landing was carried out to the north of the Gustav Line at Anzio on 22 January in an attempt to outflank the German positions, but the forces there were unable to break out from the beachheads until late May, by which time the Germans had already withdrawn northwards. Throughout the early months of 1944 RAF Spitfires and Kittyhawk fighter-bombers, Boston and Maryland medium bombers and Wellington and Liberator heavy bombers had attacked the Italian road and railway infrastructure, as well as carrying out close air support for ground troops and maintaining air supremacy over the battlefield. Rome was liberated on 4 June.

A Mar tin Baltimore IV of 69 Squadron over Malta. The type was used by the RAF exclusively in the Middle East and Mediterranean theatre, where it was an important part of the light bomber force of the Desert Air Force. (Flintham)

Operating from southern Italy on the night of 8 April 1944, three Liberators and 19 Wellingtons dropped 40 mines into the River Danube near Belgrade. This raid was the first raid in a seven-month campaign by the Wellingtons of 37, 40, 70, 104, 142 and 150 Squadrons with the Liberators and Halifaxes of 178 and 614 Squadrons to disrupt barge traffic on the River Danube. Under flares dropped by the Halifaxes and Liberators, the Wellingtons dropped 354 mines during the following month. Eventually the river would be virtually closed to traffic, particularly the vital coal and oil transporting barges, thanks to nearly 1,400 mines dropped by Wellingtons and also to night anti-shipping sorties by Beaufighters of 255 Squadron.

At the beginning of June, the Balkan Air Force was formed, which eventually would include the Spitfires of 32, 73 and 253 Squadrons, Hurricanes of 6 Squadron, North America P-51 Mustangs of 213 and 249 Squadrons, Beaufighters of 39 and 108 Squadrons along with Greek and Yugoslav RAF squadrons, three SAAF squadrons and Italian Co-Belligerant Air Force. The main thrust of these forces was to interdict the railway lines between Zagreb, Belgrade and Skopje and RAF Spitfires and Mustangs accounted for 262 locomotives in the first month of operations.

A formation of North American B-25 Mitchell II light bombers from 180 Squadron. The unit attacked the headquarters of Panzer Gruppe West on 10 June 1944. Over 800 Mitchells were delivered to the RAF and after D-Day, those of the 2nd TAF continued to support the Alllied advance through the Low Countries and into Germany. (Popperfoto/Getty)

D-DAY

On the night of 5 June 1944, some 14 Albermarles from 295 and 570 Squadrons dropped the lead elements of 3rd Parachute Brigade into Normandy; the rest of the brigade followed a short time later in 108 Dakotas provided by 48, 233, 271, 512 and 575 Squadrons. Additionally, six Horsa gliders towed by Halifaxes from 298 and 644 Squadrons delivered two companies of the 2nd Oxford & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry onto a crucial bridge across the Caen Canal. Another 129 aircraft carried 5th Parachute Brigade to its drop zones in Normandy. Overnight, 16 Lancasters of 617 Squadron dropping ‘Window’ radar jamming material simulated the movement of a large naval armada crossing the English Channel towards Cap d’Antifer and the Stirlings of 218 Squadron performed a similar diversionary task towards Boulogne. Dummy paratroops as well as pyrotechnics designed to simulate small arms fire were dropped by Halifaxes and Stirlings of 138, 149 and 161 Squadrons into northwest France.

The main landings early the following morning were preceded by a barrage by over 1,000 heavy bombers against the German coastal batteries. Massed fighter squadrons ensured Allied air supremacy over the beaches and Mustangs of 2 Squadron carried out fire direction for naval guns. Fighter-bombers were also on call for close air support if necessary. In the evening a force of 256 gliders, closely escorted by 15 squadrons of Spitfires carried supplies to the airborne forces.

The weather was poor over the next four days, but 19 squadrons of Typhoons carried out armed reconnaissance beyond the beachhead area, targeting German motor transport and armoured vehicles. By night the heavy bombers of Bomber Command and the USAAF attacked the railway infrastructure in northern France, while Mosquitoes carried out night intruder operations against road and rail traffic. An airstrip was established at Asnelles on 7 June and was initially used for refuelling and re-arming, but within a few days it became a permanent base for a Canadian Spitfire Wing. On 10 June, a force of 40 Typhoons from 181, 182, 245 and 247 Squadrons plus 61 North American B-25 Mitchells from 98, 180, 226 and 320 (RNLAF) Squadrons carried out a successful attack on the headquarters of the German Panzergruppe West.

Throughout the landings, Coastal Command was able to keep German naval forces away from the Allied fleet and the Beaufighters of 144 and 404 Squadrons with the Mosquitoes of 248 Squadron drove off three German destroyers in the Brest area. Additionally, 25 U-boats were attacked between 7 and 11 June. On 15 June, the combined North Coates and Langham strike wings carried out a successful anti-shipping strike off the Dutch coast. Unfortunately, as the year progressed, U-boats were becoming more difficult to detect with the introduction to some submarines of the Schnorkel device which enabled them to remain submerged for longer; but throughout July 1944, a total of 45 were attacked and during the same period seven major anti-shipping strikes were also carried out.

Although originally designed as a bomber, the Armstrong-Whitworth Albermarle was successfully used as a glider tug. The type was used during the airborne assaults on Sicily, Normandy and Arnhem. This aircraft was used by 511 Squadron in the transport role. (Flintham)

Interspersed with their night activities, Bomber Command aircraft also carried out daylight raids, starting on 14 June when 221 Lancasters and 21 Mosquitoes bombed Le Havre. A similar-sized force attacked Boulogne the following day. Thereafter, the preparation and launch sites for the Fieseler Fi 103 (‘V-1’) flying bomb and Mittelwerk Aggregat A4 (‘V-2’) ballistic missile in northern France were attacked on an almost daily basis. The V-1 had made its debut on 13 June and the first line of defence against these weapons was the Tempests of 3, 56 and 486 Squadrons; Mosquitoes, Spitfires, and from July the Gloster Meteors of 616 Squadron, were also successful against the V-1. The V-1 attacks against southern England continued until September 1944 when the launch sites were overrun by Allied forces.

On 30 June 258 RAF bombers attacked a road junction at Villers Bocage, escorted by nine squadrons of Spitfires, marking the beginning of heavy bomber operations in the Caen area. Oboe equipment was fitted to some Lancasters from early July, enabling the heavy bomber force to drop bombs with reasonable accuracy through cloud. The technique was first used on 11 July against the V-1 site at Gapennes, near Abbeville. RAF aircraft attacked Caen itself on 7 and 18 July. Although the main operational focus for Bomber Command had been in northern France during June and July, small-scale raids on German cities had continued throughout the period; on 23 July, a raid on Kiel by 629 Lancasters, Halifaxes and Mosquitoes was the first large-scale attack on Germany for two months.

Douglas C-47 (DC-3) Dakotas of 267 Squadron were deployed to evacuate over 1,000 partisan casualties from Yugoslavia in August 1944. Some 2,000 of the type were supplied to the RAF and saw operational service in Europe, the Middle East and the Far East. (Flintham)

During July and August 1944, a number of daylight low-level precision attacks were carried out by Mosquitoes. On 14 July, Mosquitoes from 21, 464 and 487 Squadrons escorted by 12 Mustangs from 65 Squadron bombed the SS barracks in the Chateau de Marieville at Bonneuil-Matours in support of Special Forces operations in that area. The attack was followed up with a further raid on 2 August by Mosquitoes of 107 Squadron on the same SS unit which was now housed in the nearby Château du Fou. On the same day, nine Mosquitoes from 305 Squadron bombed a German sabotage training school at Château Maulny near Angers. Three days previously five Mosquitoes from 613 Squadron had bombed the Château de Trévarez which was being used as a recreation centre for U-boat crews after patrols. On 18 August, 14 Mosquitoes from 613 Squadron bombed a German headquarters in Égletons near Poitiers and on the last day of the month six Mosquitoes from 305 Squadron destroyed a large petrol storage at Nomeny near Nancy.

Although German armour was very effective against Allied tanks, it was also extremely vulnerable to air attack. A counterattack by German tanks on 7 August was defeated by rocket-armed Typhoons which flew nearly 300 sorties that afternoon. The main German withdrawal from the Falaise pocket turned into a massacre of similar proportions to that of the Wadi Fara in 1918. A force of 32 Typhoons from 164, 183, 198 and 609 Squadrons wrought havoc on the German tanks as they attempted to break out near Chambois on 20 August.

A second front opened in France on 15 August with landings by Allied troops in the south of France between Cannes and Saint Tropez. Just as in northern France, the mainly US amphibious operations were supported by tactical air power, including nine squadrons of RAF Spitfires.

KOHIMA & IMPHAL

While the Allied armies in northern France attempted to break out from Normandy, the 14th Army sought to fight its way out of India. On 5 June 1944, the Aradura Spur, three miles south of Kohima, was captured from the Japanese, marking the beginning of the breakout from Kohima. Allied troops from Kohima and Imphal joined up on 22 June and the advance continued, supported by the Hurricane and Vultee Vengeance-equipped squadrons, forcing the Japanese back into Burma. Nearly all supplies had to be flown to the front-line units and as the monsoon broke the Dakotas of 31, 52, 62, 117, 194, 353, 435 (RCAF), 436 (RCAF) and 357 Squadrons, plus the eight US squadrons of the Combat Cargo Task Force found themselves delivering stores in torrential rain under a 200ft cloud-base. The pressure was maintained on the Japanese rear areas by Beaufighters of 177 and 211 Squadrons which attacked ports and boat traffic on the River Chindwin as well as railway rolling stock. They also ranged as far as the Tenasserim coast in southern Burma, seeking out coastal shipping. Wellingtons also laid mines in the waterways. In a novel role for the aircraft, Hurricanes were also used to spray DDT pesticide to counter insect-borne disease in the vicinity of Tamu in the Kabaw Valley.

Tiddim was recaptured on 19 October, followed a week later by a Japanese strongpoint known as Vital Corner. This latter action had been preceded by a heavy barrage which included artillery and bombing by four Hurricane squadrons. The Liberators of 99, 159, 215, 355 and 356 Squadrons were also used on occasions for ‘earthquake’ operations to bomb pinpoint targets such as bunkers, often after a flight of nearly 1,000 miles; however, they more usually concentrated their efforts against the railway system deeper in Burma.

In the Far East, the work of the photo-reconnaissance squadrons, 681 Squadron flying Spitfires and 684 Squadron flying Mosquitoes, proved to be even more vital than it was in Europe. The quality of maps of Burma was generally poor, so the photographic survey carried out by the two RAF squadrons and their USAAF counterparts became the main source of accurate mapping.

ITALY & THE BALKANS

Despite the Allied air supremacy over Italy, the German army fought strongly on the ground and was able to conduct an orderly fighting retreat northwards. Over the summer months, Allied tactical aircraft were flying 1,000 sorties a day against lines of communication and the road and railway infrastructure in northern Italy. Operations were mounted into Central Europe from the Italian bases, too, including missions against the oil installations at Ploiești, which were attacked by RAF Halifaxes, Liberators and Wellingtons on the night of 9 August. In the week before that raid, however, Halifaxes from 148 Squadrons and 1586 (Polish Special Duties) Flight had flown long-range missions to Warsaw to drop supplies to Polish forces engaged in the Warsaw Uprising. These units were joined by 614 Squadron (Halifax) and 34 SAAF squadrons equipped with the Liberator: 31 of these had been redeployed from southern France. The Liberators of 178 Squadron also replaced the Halifaxes of 614 Squadron in early September. The first mission to Warsaw was flown on the night of 4 August and the last, by SAAF Liberators, on the night of 21 September; these sorties involved large aircraft flying a low speed and low altitude over a heavily defended area, so losses were high: 31 aircraft were lost from 181 aircraft despatched, including 15 of the 16 crews of 1586 Flight.

The Balkan Air Force continued its work over Yugoslavia, as did the Halifaxes and Liberators of 148 and 614 Special Duties Squadrons, which between them dropped a considerable quantity of arms and supplies to partisan forces. Support to partisans included the evacuation of over 1,000 casualties from Yugoslavia on 23 August: the first sortie was flown by six Dakotas of 267 Squadron, escorted by 18 Mustangs and Spitfires.

The Allied advance through Italy continued northwest until August 1944, when the frontline stabilized along the Gothic Line, running between Pisa and Rimini. On the night of 25 August, Halifaxes and Liberators marked and illuminated railway marshalling yards and canal dock areas near Ravenna, for a force of Wellingtons and by day Baltimores and Bostons flew armed reconnaissance sorties looking for targets of opportunity in the same area. A month later the offensive restarted and Kittyhawks and Spitfires flew close air support missions against gun and mortar positions as well as fortified strongpoints as the army fought around Rimini. Rimini itself fell three days later, but there was no further breakthrough and the front stagnated along the Gothic Line.

Axis shipping had largely been driven from the Adriatic Sea during 1944 thanks to the attentions of the coastal air force. Marauders of 14 Squadron carried out coastal reconnaissance to locate targets for anti-shipping Beaufighters of 272 Squadron with notable success. The most spectacular achievement of this combination of forces was the sinking of the Italian liner Rex on 8 September to prevent it being used to blockade Trieste harbour.

DEFEATING THE U-BOATS

In September 1944, all U-boats based in France, regardless of their preparedness for operations, put to sea to escape Allied forces and to establish new bases in Norway. Between 11 and 26 September, five U-boats were sunk by Liberators of 206, 220, 224 and 423 (RCAF) Squadrons in a sea area stretching from the Azores to the Norwegian coast. As German forces in Norway became ever more reliant on shipborne supplies, the work of the strike wings at Banff (comprising 143, 235 and 248 Squadrons operating Mosquitoes), Dallachy (comprising the Beaufighter-equipped 144, 404 (RCAF), 455 (RAAF) and 489 Squadrons) and North Coates (Beaufighters of 236 and 254 Squadrons) took on greater strategic importance. Between them, the three wings were effective in restricting shipping off the Norwegian, Danish and German coasts. The Halifaxes of 58 and 502 Squadrons carried out the same role at night.

Limited by the longer distance to the Atlantic Ocean, but equipped with Schnorkel devices, which enabled them to stay submerged and thus be harder to detect, U-boats started to operate in waters much closer to the UK: for example, U-boats were found in the Irish Sea and Bristol Channel, as well as in the northwest and southwest approaches. The number of Wellington Leigh Light squadrons was increased with the transfer of 14 and 36 Squadrons from the Mediterranean. Two US Navy Liberator squadrons and a Ventura squadron also bolstered the anti-submarine force. In early 1945 Sonobuoys were introduced into service with ten Liberator squadrons, giving them a better chance of locating submerged U-boats.

Two Supermarine Spitfire IX fighters from 241 Squadron over Central Italy. The squadron operated in the tactical reconnaissance and ground-attack roles during the Italian campaign. (© IWM TR 1531)

ARNHEM

In mid-September, the German forces had withdrawn into the Netherlands and later that month a daring attempt was made to push across the natural barriers of the Maas and Rhine rivers, by dropping airborne forces ahead of the main armoured advance to secure bridgeheads. On 17 September 1944 paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Division were delivered to their drop zones near Arnhem by Dakotas of 48, 233, 271, 437 (RCAF), 512 and 575 Squadrons. On the same day, Albermarles of 296 and 297 Squadrons, Stirlings of 190, 196, 295, 299, 570 and 625 Squadrons and Halifaxes of 298 and 644 Squadrons towed a fleet of 320 Horsa gliders as well as 15 heavy-lift General Aircraft Hamilcar gliders to the assault landing grounds. A second ‘lift’ of troops and equipment in 296 Horsas and a further 15 Hamilcars was carried out the next day. Over the next few days the transport aircraft attempted to keep the airborne troops resupplied by air, but the area was heavily defended by the German army: a number of transport aircraft were shot down and only a small proportion of the supplies dropped could be retrieved by the British troops. However, RAF Spitfires and Tempests were able to keep Luftwaffe aircraft away both from Arnhem and the bridgehead established by 82nd and 101st Airborne Division (US Army) at Nijmegen.

GREECE

By mid-October 1944, the Germans had been driven out of Belgrade and most of the Greek islands were being retaken but strong German garrisons remained in Corfu and in northwest Greece. Night intruder missions by Allied aircraft against airfields around Athens restricted the Luftwaffe’s freedom of movement in the theatre. During the first week of October the tactical squadrons of the Balkan Air Force concentrated on close air support missions in southern Albania, before resuming the offensive against the railway network. Meanwhile the Wellingtons and Liberators ranged further afield to attack marshalling yards as far away as Linz and Vienna. Unfortunately, by the time that Athens was liberated, the beginnings of a civil war in Greece were already simmering. Violence broke out between the Greek factions soon after British troops arrived in early December 1944 and RAF aircraft were called in to attack positions held by communist ELAS guerrillas. The Spitfires of 73 and 94 Squadrons were used for strafing and bombing, supplemented by rocket-armed Beaufighters from 39 and 108 Squadrons. The situation was stabilized, albeit temporarily, by the end of the month.

THE BOMBING CAMPAIGN CONTINUES

Most of the German naval forces were now concentrated in Norway, including the battleship Tirpitz. Berthed in Kåfjord, Tirpitz was beyond the range even of Lancasters based in the UK, but in early September aircraft of 9 and 617 Squadrons deployed to the Russian airfield at Yagodnik, near Arkhangelsk, to put them within reach of the ship. On 15 September, 27 Lancasters armed with a mixture of 12,000lb ‘Tallboy’ bombs and sea mines attacked the Tirpitz from Yagodnik. Weapon aiming was difficult because of a very effective smoke screen obscuring the battleship, but sufficient damage was caused for her to be moved to a new berth near Tromsø.

While Allied ground forces advanced across the Netherlands, German forces, including strong shore batteries, on the island of Walcheren on the Scheldt estuary blocked Allied access to the port facilities at Antwerp. Since Walcheren was a polder, lying below sea level, it was decided to flood the island and then mount an amphibious assault to capture it. On 3 October, Oboe-equipped Mosquitoes marked positions on the sea dykes for 252 Lancasters to bomb. A breach was created and the island began to flood; a follow-up operation by 121 Lancasters four days later widened the breach and on 11 and 12 October large formations of Lancasters bombed the gun emplacements at Breskens, on the southern bank of the Scheldt, as well as gun positions on Walcheren itself, near Flushing. A further breach of the dyke near Westkappelle was made by Lancasters on 17 October. During this period, medium bombers also attacked targets on the island. The amphibious assault was carried out in appalling weather on 1 November, supported by Typhoons. The first Typhoon unit in action over the beachhead was 183 Squadron.

An Airspeed Horsa glider, towed by a Halifax tug of 644 Squadron. A Horsa could carry 20–25 troops or 7,100lb of cargo and once released from tug, it could glide at 100mph. Over 600 of the type were used during the air assault at Arnhem. Gliders were used again for the crossing of the Rhine in March 1945. (Pitchfork)

By this stage of the war, thanks to electronic navigation aids, target marking and ‘Master Bomber’ techniques, Bomber Command was capable of hitting a city-sized target with reasonable accuracy. After the Allied advance through the Low Countries, the RAF’s heavy bomber force was switched from bombing tactical targets in support of the land forces back to a strategic campaign against German oil production. The loss of radar stations in Belgium and the Netherlands robbed the German defences of early warning of raids, making daylight missions less vulnerable, so RAF bombers could operate by both day and night. In mid-October, a series of large-scale bombing raids against Duisburg was intended to demonstrate the Allies’ overwhelming air superiority. At dawn on 14 October 1944, a force of 957 Lancasters, Halifaxes and Mosquitoes with a fighter escort dropped nearly 3,600 tons of explosives on Duisburg. The attack was followed later in the day by 1,250 USAAF bombers escorted by 749 fighters which bombed targets near Cologne. That night diversionary attacks, including one by 233 Lancasters against Brunswick as well as attacks by Mosquitoes on Hamburg, Berlin and Mannheim, were carried out while the main force of 498 Lancasters, 468 Halifaxes and 39 Mosquitoes revisited Duisburg. Thus, over 2,000 RAF bombers had visited Duisburg in a single day. During the month there were further large raids against Stuttgart (on 19 October), Essen (on 23 and 25 October) and Cologne (on 28 and 30 October).

As well as large-scale attacks by heavy bombers, a number of low-level precision attacks against high value German targets were carried out by Mosquitoes and Typhoons. These included the bombing of a German army headquarters building in Dordrecht on 24 October by Typhoons of 193, 197, 257, 263 and 266 Squadrons. Five days later, and despite poor weather, 24 Mosquitoes from 21, 464 and 487 Squadrons, escorted by eight Mustangs from 315 (Polish) Squadron successfully attacked the Gestapo headquarters building at Aarhus, Denmark. Unfortunately, an attempt by 12 Mosquitoes from 627 Squadron to bomb the Gestapo headquarters in Oslo on 31 December was not a success.

At her new mooring near Tromsø, the Tirpitz was now within range of Lancasters operating from the UK. On 12 November 1944, a force of Lancasters from 9 and 617 Squadrons, all carrying 12,000lb ‘Tallboys’ took off from Lossiemouth to bomb the ship. This attack was a complete success and after sustaining two direct hits, the Tirpitz capsized.

BURMA

On 2 January 1945, aerial reconnaissance indicated that the Japanese had pulled back from Akyab Island and the island was recaptured the following day. Nine days later an amphibious assault was launched from Akyab against Myebon on the mainland. A force of 28 Japanese Nakajima Ki-43 (Oscar) and seven Nakajima Ki-84 (Frank) fighter-bombers attempted to intervene, but they were beaten off by Spitfires of 67 Squadron, which shot down five ‘Oscars.’ Hurricanes laid smoke screens to shield the landings, which were also supported by Republic P-47 Thunderbolts of 134 Squadron and USAAF B-25 Mitchell bombers. As the troops of 3 Commando Brigade pushed towards Kangaw, the Thunderbolts of 5, 123, 135 and 258 Squadrons flew ‘cab rank’ close air support missions. On 21 January, the island of Ramree was also captured, with support from Liberators and Thunderbolts.

Meanwhile, the 14th Army advanced into central Burma; the army was reliant on air supply for the operation by the Combat Cargo Task Force and when USAAF C-47 Skytrains were re-allocated to move Chinese troops back to China, two more RAF Dakota squadrons, 238 and 267 Squadrons, were dispatched to Burma. The army advance was two-pronged: the main thrust by 33 Corps was to Mandalay while 4 Corps carried out an outflanking manoeuvre to the west towards the River Irrawaddy at Bagan and thence to Meiktila. Throughout the campaign, Thunderbolts provided close air support. Beaufighters continued to interdict railways and waterways and Liberators attacked supply dumps, including one near Rangoon on 11 February. All of these aircraft were also available for ‘earthquake’ missions to lay down a barrage or to attack bunkers and strongpoints. Spitfires ensured that Japanese aircraft stayed clear of the battlefield and that Japanese reconnaissance aircraft were unable to detect 4 Corps’ movement.

The Irrawaddy was crossed at Singu near Bagan on 13 February 1945 after an ‘earthquake’ bombing attack on 8 February which included the Thunderbolts of 79, 146 and 261 Squadrons. Thabuktan airfield near Meiktila was taken on 16 February, enabling Dakotas to fly in reinforcements directly from Imphal. The main airfield at Meiktila was also recaptured shortly afterwards. During February 60,000 tons of supplies were also flown into Meiktila by Dakotas. The Japanese counterattacked and the RAF Regt units on the airfield, 2708 Field Squadron RAF Regt supplemented by flights from 2941 and 2968 Field Squadrons and 2963 Light Anti-Aircraft Squadron RAF Regt, fought an aggressive action to defend it.

Further to the east, Japanese aircraft based at Pyinmana, 150 miles south of Mandalay, began to attack 33 Corps positions and on 12 February the Thunderbolts of 123, 134, 258 and 261 Squadrons carried out strafing attacks against the airfields. The following day British and Indian troops started to cross the Irrawaddy at Myinmu, about 30 miles west of Mandalay. A week later Hurricanes from 20 Squadron were patrolling the jungle near Myinmu, when they found some suspicious buildings. It transpired that these were 12 camouflaged Japanese tanks, which were attacked and destroyed. The battles raged around Meiktila and Mandalay over the next month. Mandalay fell on 20 March, after Thunderbolts of 79 and 261 Squadrons and Hurricanes of 42 Squadron bombed the walls of Fort Dufferin, the old Burmese royal palace, which had walls 45ft thick.

A very rare image of a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt II of 60 Squadron over Burma. A total of 830 Thunderbolts saw service with the RAF in Burma, where the aircraft were used for the close air support of ground forces. (Flintham)

While 4 Corps advanced along the road from Meiktila towards Rangoon from the north, a combined airborne and amphibious assault was prepared to take Rangoon from the south. On 1 May 1945 the Thunderbolts of 5, 30 and 258 Squadrons softened up Japanese gun positions, while airborne troops were delivered to Elephant Point by USAAF C-47 Skytrains. The landing the following day was supported by Thunderbolts of 30, 134, 146 and 258 Squadrons, but it proved to be unopposed as the Japanese had withdrawn to Moulmein. Rangoon was recaptured on 3 May.

BOMBING ITALY & GERMANY

With operations in northwest Europe understandably taking priority for resources, Allied armies in northern Italy were unable to launch an offensive against the Gustav line over the winter. Instead Allied aircraft conducted an interdiction campaign against the lines of communication to the north of the Gustav Line with the intention of cutting off the German army from its supply network. Links to the Brenner Pass were frequently cut, the marshalling yards at Verona were bombed and the entire rail network in northeast Italy was subject to intense attacks. Coastal shipping was also targeted and on 21 March 1945 a force of over 100 fighter bombers, comprising the Kittyhawks of 250 and 450 (RAAF) Squadrons with the Mustangs of 3 (RAAF), 5 (SAAF), 112, and 260 Squadrons carried out a very accurate and highly destructive bombing raid on the docks and railway facilities at Venice. Much damage was caused to the target area, but the cultural centre of the old city remained unscathed.

Personnel of 2963 Light Anti-Aircraft (LAA) Squadron RAF Regiment man a 20mm Hispano anti-aircraft gun at Meiktila. Apart from providing air defence to the airstrip, the squadron gunners joined the other RAF Regiment personnel to defend the airfield against aggressive attacks by Japanese infantry. (Pitchfork)

On 9 April, after an intense bombardment by a force of nearly 1,000 heavy and medium bombers in the vicinity of Lugo, the army pushed forward with support from tactical aircraft and crossed the River Senio. That night the Liberators of 37, 40, 70 and 104 Squadrons continued to bomb German positions, which were marked from the ground by coloured artillery shells, and Lugo was captured the following day. The advance then continued, reaching Verona, Spezia and Parma on 25 April and Turin on 30 April. The German forces surrendered on 24 April and a ceasefire was enforced from 2 May.

The strategic bombing campaign against German oil production and lines of communication continued into early 1945, but in mid-February it was thought that a series of powerfully destructive raids might be enough to paralyse the German administration and bring about early capitulation. The target chosen for the first raid was the city of Dresden, a cultural centre with little industry. The initial raid, which was to have been carried out by the USAAF on 13 February 1945, was cancelled because of the weather in the target area. However, the weather improved that evening and two waves, comprising 244 Lancasters and 9 Mosquitoes in the first and 529 Lancasters in the second, bombed Dresden that night. The following day USAAF bombers attacked the railway marshalling yards. Although the attack on Dresden was indeed powerfully destructive, the raid on Chemnitz the next night, during which most aircraft completely missed the city, was an indication of the inherent inconsistency of large-scale bomber attacks against even relatively large-sized targets.

However, smaller, well-equipped specialist forces could achieve spectacularly accurate results. On 14 March, 28 Lancasters from 9 and 617 Squadrons attacked the Schildescher Viaduct, an important railway bridge near Bielefeld. Most aircraft carried 12,000lb ‘Tallboy’ bombs, but one of the 617 Squadron aircraft was armed with a much larger 22,000lb ‘Grand Slam’ bomb. The concentration of heavy bombs successfully dropped a number of spans of the viaduct. Seven days later 18 Mosquitoes from 21, 464 and 487 Squadrons, accompanied by an escort of 28 Mustangs from 64, 126 and 234 Squadrons carried out a successful low-level attack on the Gestapo headquarters in the Shellhuis in Copenhagen. Six Mosquitoes drawn from the same units carried out another attack on a Gestapo headquarters in Denmark, this time in Odense, on 17 April. On this mission, the Mosquitoes were escorted by eight Mustangs from 129 Squadron.

On 18 April 1945 Bomber Command revisited Heligoland, nearly five years after the disastrous raids of the first days of the war. On this occasion 943 Lancaster, Halifax and Mosquito bombers dropped nearly 5,000 tons on the island, for the loss of just three Halifaxes.

THE END IN EUROPE

After the abortive attempt to cross the River Rhine at Arnhem in September 1944, another crossing was forced at Wesel on 23 March 1945. In the days leading up to the operation Typhoons carried out armed reconnaissance sorties in the area, attacking military targets including the destruction of a German airborne forces supply depot on 21 March. Spitfires and Tempests also flew fighter sweeps to draw Luftwaffe fighters into battle and on 22 March a formation of 32 Tempests shot down five of 12 FW190 fighters which attempted to intervene. On the day of the crossing, Wesel was bombarded by a force of 77 Lancasters, while a further 212 Lancasters carried out a second attack on Wesel that night. The crossing of the river was also preceded by airborne landings to establish a bridgehead on the eastern side of the river: Albermarles, Halifaxes and Stirlings delivered 440 gliders to the landing zone. All the army operations were supported by Typhoons flying ‘cab rank’ close air support sorties. Over the next few days the bridgehead was consolidated and expanded under the air cover of the Spitfire and Tempest squadrons, which shot down 12 FW190 aircraft on 24 March.

On the night of 7 April, 47 Stirlings dropped two French battalions of the Special Air Service (SAS) near Groningen. In the battle to capture Groningen, these forces were supported by Typhoons, which also dropped ammunition and supplies to the troops on 8 and 12 April.

Allied forces advanced steadily across northern Germany, closely supported by the tactical air force; the British army’s line of advance was towards Bremen, Hamburg and Lübeck, reaching the River Elbe in late April. At this point Luftwaffe aircraft, operating at short range from their remaining bases, attempted to fight back, but they were overwhelmed by Allied fighters.

During March and April, Liberators of 206 and 547 Squadrons had attempted to intercept U-boats working up in the Baltic Sea, but they had no success. However, in order to reach the operational bases in Norway, the U-boats had to negotiate the narrows of the Kattegat and Skagerrak. The Banff strike wing sank four U-boats in the Skagerrak in April and between 2 and 7 May, a further 14 U-boats were sunk in the Kattegat including five by the North Coates strike Wing, and seven by Liberators of 86, 206, 224, 311 (Czech) and 547 Squadrons.

Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawk IV fighter-bombers of 450 Squadron RAAF armed with 250lb bombs. These aircraft carried out a precision bombing raid on the dock facilities near Venice on 21 March 1945. (Pitchfork)

In one of the last attacks by Bomber Command, 359 Lancasters and 16 Mosquitos attacked Wolfschanze, Hitler’s mountain retreat at Berchtesgaden, on 25 April. Soon afterwards, Bomber Command suspended offensive operations. Instead, between 29 April and 8 May, Lancasters and Mosquitoes dropped 6,685 tons of food and supplies to Dutch civilians suffering from food shortages in the German-occupied parts of the Netherlands. In a similar timeframe, heavy bombers and transport aircraft commenced Operation Exodus, the repatriation of Allied prisoners of war. In May alone, some 72,000 were flown from Europe to the UK.

In late 1944, 501 Squadron, equipped with the Hawker Tempest V, was deployed to RAF Manston for ‘Anti-Diver’ patrols to intercept German V-1 ‘Doodlebug’ flying bombs. The fastest of the RAF front-line fighters of the day, Tempests accounted for over 600 V1s. (Charles E. Brown/RAFM/Getty)

Germany surrendered on 8 May 1945. The RAF units in Germany remained there, forming the British Air Forces of Occupation (BAFO) to ensure peace and to oversee the dismantling of the Luftwaffe.

A Liberator B VI of 354 Squadron over the Bay of Bengal. The last bombing mission of the war was carried out by Liberators of 99 and 356 Squadrons operating from the Cocos Islands on 7 August 1945. (Pitchfork)

THE END IN BURMA

The Liberator squadrons in the Far East carried out strategic operations at extremely long ranges: it was not unusual for aircraft to fly over one thousand miles to their targets. One of the longest such missions was mounted on 5 June 1945 when seven Liberators attacked the railway yards at Surasdhani on the Bangkok–Singapore railway in the far south of Thailand. The flight of 2,400 miles through monsoon weather lasted 17 hours. In another long-range mission ten days later, Liberators from 99, 159 and 356 attacked and sank a large oil tanker which had been located by a Sunderland in the Bay of Siam.

After the fall of Mandalay and Rangoon a sizeable Japanese army was trapped in the Pegu Yomas mountain range in eastern Burma, between the Irrawaddy and Sittang rivers. On 3 July 1945, the Japanese attempted to break out across the Sittang River, but their plans had been compromised and British forces were ready for them. Despite a cloud base of only 1,000ft, Thunderbolts and Spitfires carried out ‘cab rank’ close support for the army, attacking enemy troop concentrations and rivercraft. On 4 July Thunderbolts from 42 Squadron neutralized three Japanese field guns. Further to the south near Moulmein, Spitfires of 273 and 607 Squadrons, as well as Mosquitoes, operated in concert with Force 136, a Special Forces unit working with local resistance fighters. They killed around 500 Japanese troops near Hpa-An on 1 July and repeated the success a 14 days later. The battle of the Sittang Bend lasted until 29 July, during which time the Thunderbolts and Spitfires attacked the enemy almost continuously. The Japanese lost more than 10,000 men killed. Although the Japanese surrendered on 14 August, operations continued in Burma until 20 July when Thunderbolts of 42 Squadron attacked Japanese troops who had not surrendered.

IMMEDIATELY POST WAR

With the end of the war in Japan, operations commenced to rescue and repatriate Allied prisoners of war and internees. The Dakotas of 31 Squadron operated initially from Seletar, but soon moved to Kemajoran (Jakarta) in Java, where they joined the Thunderbolts of 60 and 81 Squadrons as well as Spitfires of 28 Squadron and Mosquitoes of 110 Squadron. Having rid themselves of the Japanese, the Indonesians were loath to restore the colonial Dutch government and an independent state was declared, which was hostile to both British and Dutch interests. The Thunderbolts, Spitfires and Mosquitoes attempted to maintain the safety of the Dakotas and also covered the evacuation of Dutch civilians. In Vietnam, there was a similar reluctance to welcome the old colonial master and the Spitfires of 273 Squadron were required to carry out large-formation ‘shows of force’ to deter aggression by the Viet Minh forces until the French retook control of the country.

In six years of war the RAF had expanded to a peak of 500 operational squadrons and had fought simultaneous campaigns over three continents and two oceans. The service had overcome its shortcomings in the early years of the war and it had evolved into an extremely effective fighting force.

A Spitfire FR XIV of 273 Squadron. At the end of World War II, the unit was based at Tan Son Nhut, Vietnam in support of efforts to maintain law and order during the transition from Japanese occupation to the resumption of French colonial rule. (Flintham)