Since World War II

| The Developed Democracies Since World War II |

|

4 |

In the preceding chapters I have argued, among other things, that associations to provide collective goods are for the most fundamental reasons difficult to establish, and that therefore even those groups that are in situations where there is a potential for organization usually will be able to organize only in favorable circumstances. As time goes on, more groups will have enjoyed favorable circumstances and overcome difficulties of collective action. The interest of organizational leaders insures that few organizations for collective action in stable societies will dissolve, so these societies accumulate special-interest organizations and collusions over time (Implication 2). These organizations, at least if they are small in relation to the society, have little incentive to make their societies more productive, but they have powerful incentives to seek a larger share of the national income even when this greatly reduces social output (Implication 4). The barriers to entry established by these distributional coalitions and their slowness in making decisions and mutually efficient bargains reduces an economy’s dynamism and rate of growth (Implication 7). Distributional coalitions also increase regulation, bureaucracy, and political intervention in markets (Implication 9).

If the argument so far is correct, it follows that countries whose distributional coalitions have been emasculated or abolished by totalitarian government or foreign occupation should grow relatively quickly after a free and stable legal order is established. This can explain the postwar “economic miracles” in the nations that were defeated in World War II, particularly those in Japan and West Germany. The everyday use of the word miracle to describe the rapid economic growth in these countries testifies that this growth was not only unexpected, but also outside the range of known laws and experience. In Japan and West Germany, totalitarian governments were followed by Allied occupiers determined to promote institutional change and to ensure that institutional life would start almost anew. In Germany, Hitler had done away with independent unions as well as all other dissenting groups, whereas the Allies, through measures such as the decartelization decrees of 1947 and denazification programs, had emasculated cartels and organizations with right-wing backgrounds.1 In Japan, the militaristic regime had kept down left-wing organizations, and the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers imposed the antimonopoly law of 1947 and purged many hundreds of officers of zaibatsu and other organizations for their wartime activities.2 (In Italy, the institutional destruction from totalitarianism, war, and Allied occupation was less severe and the postwar growth “miracle” correspondingly shorter, but this case is more complex and will be discussed separately.)* The theory here predicts that with continued stability the Germans and Japanese will accumulate more distributional coalitions, which will have an adverse influence on their growth rates.

Moreover, the special-interest organizations established after World War II in Germany and Japan were, for the most part, highly encompassing. This is true of the postwar labor union structure of West Germany, for example, and of the business organization, Keidanren, that has played a dominant role in economic policymaking in Japan. The high growth rates of these two countries also owe something to the relatively encompassing character of some of the special-interest organizations they did have (and this organizational inclusiveness in turn was sometimes due to promotion by occupation authorities).3 At least in the first two decades after the war, the Japanese and West Germans had not developed the degree of regulatory complexity and scale of government that characterized more stable societies.

The theory also offers a new perspective on French growth experience.4 Why has France had relatively good growth performance for much of the postwar period (achieving by about 1970 levels of income broadly comparable with other advanced countries) when its investment climate has often been so inclement? The foreign invasions and political instability that have hindered capital accumulation have also disrupted the development of special-interest organizations and collusions. The divisions in French ideological life must have deepened as one upheaval after another called into question the country’s basic political and economic system. The intensity of these ideological divisions must have further impaired the development of at least the larger special-interest organizations in that country. Most notably, the development of French labor unions has been set back by periods of repression and disruption and by ideological fissures that divide the French labor movement into competing communist, socialist, and catholic unions. The competition among these semideveloped unions, often in the same workplaces, in most cases prevents any union from having an effective monopoly of the relevant work force. French unions accordingly have only a limited capacity to determine work rules or wage levels (or to make union membership compulsory, with the result that most French union members do not pay dues). Smaller groups such as trade associations and the alumni of prestigious schools (as Implication 3 predicts) have been better able to organize. But their effects on growth rates in the last two decades have been limited by considerations discussed in the next chapter, which will develop another reason why the French economy has performed better in the 1960s than its troubled history would lead us to expect.5 The foregoing argument about France has some applicability to other continental countries as well.

The logic of the argument implies that countries that have had democratic freedom of organization without upheaval or invasion the longest will suffer the most from growth-repressing organizations and combinations. This helps to explain why Great Britain, the major nation with the longest immunity from dictatorship, invasion, and revolution, has had in this century a lower rate of growth than other large, developed democracies. Britain has precisely the powerful network of special-interest organizations that the argument developed here would lead us to expect in a country with its record of military security and democratic stability. The number and power of its trade unions need no description. The venerability and power of its professional associations is also strik ing. Consider the distinction between solicitors and barristers, which could not possibly have emerged in a free market innocent of professional associations or government regulations of the sort they often obtain; solicitors in Britain have a legal monopoly in assisting individuals making conveyances of real estate and barristers a monopoly of the right to serve as counsel in the more important court cases. Britain also has a strong farmers’ organization and a great many trade associations. In short, with age British society has acquired so many strong organizations and collusions that it suffers from an institutional sclerosis that slows its adaptation to changing circumstances and technologies.

Admittedly, lobbying in Britain is not as blatant as in the United States, but it is pervasive and often involves discreet efforts to influence civil servants as well as ministers and other politicians. Moreover, the word establishment acquired its modern meaning there and, however often that word may be overused, it still suggests a substantial degree of informal organization that could emerge only gradually in a stable society. Many of the powerful special-interest organizations in Britain are, in addition, narrow rather than encompassing. For example, in a single factory there are often many different trade unions, each with a monopoly over a different craft or category of workers, and no one union encompasses a substantial fraction of the working population of the country. Britain is also often used as an example of ungovernability. In view of the long and illustrious tradition of democracy in Britain and the renowned orderliness of the British people, this is remarkable, but it is what the theory here predicts.

This explanation of Britain’s relatively slow postwar growth, unlike many other explanations, is consistent with the fact that for nearly a century, from just after the middle of the eighteenth century until nearly the middle of the nineteenth, Britain was evidently the country with the fastest rate of economic growth. Indeed, during their Industrial Revolution the British invented modern economic growth. This means that no explanation of Britain’s relatively slow growth in recent times that revolves around some supposedly inherent or permanent feature of British character or society can possibly be correct, because it is contradicted by Britain’s long period with the fastest economic growth. Any valid explanation of Britain’s relatively slow growth now must also take into account the gradual emergence of the “British disease.” Britain began to fall behind in relative growth rates in the last decades of the nineteenth century,6 and this problem has become especially notable since World War II. Most other explanations of Britain’s relatively slow growth in recent times do not imply a temporal pattern that is consistent with Britain’s historical experience with dramatically different relative growth rates,7 but the theory offered here, with its emphasis on the gradual accumulation of distributional coalitions (Implication 2), does.

There cannot be much doubt that totalitarianism, instability, and war reduced special-interest organizations in Germany, Japan, and France, and that stability and the absence of invasion allowed continued development of such organizations in the United Kingdom. My colleague Peter Murrell systematically recorded the dates of formation of those associations recorded in Internationales Verzeichnis der Wirtschaftsver-bande.8 This is, to be sure, an incomplete source, and is perhaps flawed also in other ways, but it was published in 1973 and thus cannot have been the result of any favoritism toward the present argument. Murrell found from this source that whereas 51 percent of the associations existing in 1971 in the United Kingdom were founded before 1939, only 37 percent of the French, 24 percent of the West German, and 19 percent of the Japanese associations were. Naturally, Britain also had a smaller proportion of its interest groups founded after 1949—29 percent, contrasted with 45 percent for France and 52 percent for Germany and for Japan. Britain also has a much larger number of associations than France, Germany, or Japan, and is exceeded in this category only by the far larger United States. Of course, we ought to have indexes that weight each organization by its strength and its membership, but I know of none.

Murrell also worked out an ingenious set of tests of the hypothesis that the special-interest groups in Britain reduced that country’s rate of growth in comparison with West Germany’s. If the special-interest groups were in fact causally connected with Britain’s slower growth, Murrell reasoned, this should put old British industries at a particular disadvantage in comparison with their West German counterparts, whereas in new industries where there may not yet have been time enough for special-interest organizations to emerge in either country, British and West German performance should be more nearly comparable. Thus, Murrell argued, the ratio of the rate of growth of new British industry to old British industry should be higher than the corresponding ratio for West Germany. There are formidable difficulties of definition and measurement, and alternative definitions and measures had to be used. Taking all of these results together, it is clear that they support the hypothesis that new British industries did relatively better in relation to old British industries than new German industries did in relation to old German industries. In most cases the results almost certainly could not have been due to chance, that is, they were statistically significant. Moreover, Murrell found that in heavy industry, where both industrial concentration and unionization are usually greater than in light industry, the results were strongest, which also supports the theory.9

Of the many alternative explanations, most are ad hoc. Some economists have attributed the speed of the recoveries of the vanquished countries to the importance of human capital compared with the physical capital destroyed by bombardment, but this cannot be a sufficient explanation, since the war killed many of the youngest and best-trained adults and interrupted education and work experience for many others. Knowledge of productive techniques, however, had not been destroyed by the war, and to the extent that the defeated nations were at a lower-than-prewar level of income and needed to replace destroyed buildings or equipment, they would tend to have an above-average growth rate. But this cannot explain why these economies grew more rapidly than others after they had reached their prewar level of income and even after they had surpassed the British level of per capita income.10

Another commonplace ad hoc explanation is that the British, or perhaps only those in the working classes, do not work as hard as people in other countries. Others lay the unusually rapid growth of Germany and Japan to the special industriousness of their peoples. Taken literally, this type of explanation is unquestionably unsatisfactory. The rate of economic growth is the rate of increase of national income, and although this logically could be due to an increase in the industriousness of a people, it could not, in the direct and simple way implied in the familiar argument, be explained by their normal level of effort, which is relevant instead to their absolute level of income. Admittedly, when the industriousness of those who innovate is considered, or when possible connections between level of effort and the amount of saving are taken into account,11 there could be some connection between industriousness and growth. But even if the differences in willingness to work are part of the explanation, why are those in the fast-growing countries zealous and those in the slow-growing countries lazy? And since many countries have changed relative position in the race for higher growth rates, the timing of the waves of effort also needs explaining. If industriousness is the explanation, why were the British so hard-working during the Industrial Revolution? And by this work-effort theory the Germans evidently must have been lazy in the first half of the nineteenth century when they were relatively poor, and the impoverished Japanese quite lethargic when Admiral Perry arrived.

One plausible possibility is that industriousness varies with the incentive to work to which individuals in different countries have become accustomed. These incentives, in turn, are strikingly influenced, whether for manual workers, professionals, or entrepreneurs, by the extent to which special-interest groups reduce the rewards to productive work and thus increase the relative attractiveness of leisure. The search for the causes of differences in the willingness to work, and in particular the question of why shirking should be thought to be present during Britain’s period of slower-than-average growth but not when it had the fastest rate of growth, brings us to economic institutions and policies, and to the more fundamental explanation of differences in growth rates being offered in this book.

Some observers endeavor to explain the anomalous growth rates in terms of alleged national economic ideologies and the extent of government involvement in economic life. The “British disease” especially is attributed to the unusually large role that the British government has allegedly played in economic life. There is certainly no difficulty in finding examples of harmful economic intervention in postwar Britain. Nonetheless, as Samuel Brittan has convincingly demonstrated in an article in the Journal of Law and Economics,12 this explanation is unsatisfactory. First, it is by no means clear that the government’s role in economic life has been significantly larger than in the average developed democracy; in the proportion of gross domestic product accounted for by government spending, the United Kingdom has been at the middle, rather than at the top, of the league, and it has been also in about the middle, at roughly the same levels as Germany and France, in the percentage of income taken in taxes and social insurance.13 Perhaps in certain respects or certain years the case that the British government was unusually interventionist can be sustained, but there is no escaping Brittan’s second point: that the relatively slow British growth rate goes back about a hundred years, to a period when governmental economic activity was very limited (especially, we might add, in Great Britain). Some economists have argued that when we look at the developed democracies as a group, we seem to see a negative correlation between the size of government and the rate of growth.14 This more general approach is much superior to the ad hoc style of explanation, so statistical tests along these lines must be welcomed. But the results so far are weak, showing at best only a tenuous and uncertain connection between larger governments and slower growth, with such strength as this relationship possesses due in good part to Japan, which has had both the fastest growth rate and the smallest government of the major developed democracies. A weak or moderate negative relationship between the relative role of government and the rate of growth is predicted by Implication 9.

One well-known ad hoc explanation of the slow British growth focuses on a class consciousness that allegedly reduces social mobility, fosters exclusive and traditionalist attitudes that discourage entrants and innovators, and maintains medieval prejudices against commercial pursuits. Since Britain had the fastest rate of growth in the world for nearly a century, we know that its slow growth now cannot be due to any inherent traits of the British character. There is, in fact, some evidence that at the time of the Industrial Revolution Britain did not have the reputation for class differences that it has now. It is a commonplace among economic historians of the Industrial Revolution that at that time Britain, in relation to comparable parts of the Continent, had unusual social mobility, relatively little class consciousness, and a concern in all social classes about commerce, production, and financial gain that was sometimes notorious to its neighbors:

More than any other in Europe, probably, British society was open. Not only was income more evenly distributed than across the Channel, but the barriers to mobility were lower, the definitions of status looser….

It seems clear that British commerce of the eighteenth century was, by comparison with that of the Continent, impressively energetic, pushful, and open to innovation…. No state was more responsive to the desires of its mercantile classes…. Nowhere did entrepreneurial decisions less reflect non-rational considerations of prestige and habit…. Talent was readier to go into business, projecting, and invention….

This was a people fascinated by wealth and commerce, collectively and individually…. Business interests promoted a degree of intercourse between people of different stations and walks of life that had no parallel on the Continent.

The flow of entrepreneurship within business was freer, the allocation of resources more responsive than in other economies. Where the traditional sacro-sanctity of occupational exclusiveness continued to prevail across the Channel … the British cobbler would not stick to his last nor the merchant to his trade….

Far more than in Britain, continental business enterprise was a class activity, recruiting practitioners from a group limited by custom and law. In France, commercial enterprise had traditionally entailed derogation from noble status.15

It is not surprising that Napoleon once derided Britain as a ‘'nation of shopkeepers” and that even Adam Smith found it expedient to use this phrase in his criticism of Britain’s mercantilistic policies.16

The ubiquitous observations suggesting that the Continent’s class structures have by now become in some respects more flexible than Britain’s would hint that we should look for processes that might have broken down class barriers more rapidly on the Continent than in Great Britain, or for processes that might have raised or erected more new class barriers in Britain than on the Continent, or for both.

One reason that only remnants of the Continent’s medieval structures remain today is that they are entirely out of congruity with the technology and ideas now common in the developed world. But there is another, more pertinent reason: revolution and occupation, Napoleonism and totalitarianism, have utterly demolished most feudal structures on the Continent and many of the cultural attitudes they sustained. The new families and firms that rose to wealth and power often were not successful in holding their gains; new instabilities curtailed the development of new organizations and collusions that could have protected them and their descendants against still newer entrants. To be sure, fragments of the Middle Ages and chunks of the great fortunes of the nineteenth century still remain on the Continent; but, like the castles crumbling in the countryside, they do not greatly hamper the work and opportunities of the average citizen.

The institutions of medieval Britain, and even the great family-oriented industrial and commercial enterprises of more recent centuries, are similarly out of accord with the twentieth century and have in part crumbled, too. But would they not have been pulverized far more finely if Britain had gone through anything like the French Revolution, if a dictator had destroyed its public schools, if it had suffered occupation by a foreign power or fallen prey to totalitarian regimes determined to destroy any organizations independent of the regime itself? The importance of the House of Lords, the established church, and the ancient colleges of Oxford and Cambridge has no doubt often been grossly exaggerated. But they are symbols of Britain’s legacy from the prein-dustrial past or (more precisely) of the unique degree to which it has been preserved. There was extraordinary turmoil until a generation or two before the Industrial Revolution17 (and this probably played a role in opening British society to new talent and enterprise), but since then Britain has not suffered the institutional destruction, or the forcible replacement of elites, or the decimation of social classes, that its Continental counterparts have experienced. The same stability and immunity from invasion have also made it easier for the firms and families that advanced in the Industrial Revolution and the nineteenth century to organize or collude to protect their interests.

Here the argument in this book is particularly likely to be misunderstood. This is partly because the word class is an extraordinarily loose, emotive, and misleadingly aggregative term that has unfortunately been reified over generations of ideological debate. There are, of course, no clearly delineated and widely separated groups such as the middle class or the working class, but rather a large number of groups of diverse situations and occupations, some of which differ greatly and some of which differ slightly if at all in income and status. Even if such a differentiated grouping as the British middle class could be precisely delineated, it would be a logical error to suppose that such a large group as the British middle class could voluntarily collude to exclude others or to achieve any common interest.18 The theory does suggest that the unique stability of British life since the early eighteenth century must have affected social structure, social mobility, and cultural attitudes, but not through class conspiracies or coordinated action by any large class or group. The process is far subtler and must be studied at a less aggregative level.

We can see this process from a new perspective if we remember that concerted action usually requires selective incentives, that social pressure can often be an effective selective incentive, and that individuals of similar incomes and values are more likely to agree on what amount and type of collective good to purchase. Social incentives will not be very effective unless the group that values the collective good at issue interacts socially or is composed of subgroups that do. If the group does have its own social life, the desire for the companionship and esteem of colleagues and the fear of being slighted or even ostracized can at little cost provide a powerful incentive for concerted action. The organizational entrepreneurs who succeed in promoting special-interest groups, and the managers who maintain them, must therefore focus disproportionately on groups that already interact socially or that can be induced to do so. This means that these groups tend to have socially homogeneous memberships and that the organization will have an interest in using some of its resources to preserve this homogeneity. The fact that everyone in the pertinent group gets the same amount and type of a collective good also means, as we know from the theories of fiscal equivalence and optimal segregation,19 that there will be less conflict (and perhaps welfare gains as well) if those who are in the same jurisdiction or organization have similar incomes and values. The forces just mentioned, operating simultaneously in thousands of professions, crafts, clubs, and communities, would, by themselves, explain a degree of class consciousness. This in turn helps to generate cultural caution about the incursions of the entrepreneur and the fluctuating profits and status of businessmen, and also helps to preserve and expand aristocratic and feudal prejudices against commerce and industry. There is massive if unsystematic evidence of the effects of the foregoing processes, such as that in Martin Wiener’s book on English Culture and the Decline of the Industrial Spirit, 1850-1980.20

Unfortunately, the processes that have been described do not operate by themselves; they resonate with the fact that every distributional coalition must restrict entry (Implication 8). As we know, there is no way a group can obtain more than the free market price unless it can keep outsiders from taking advantage of the higher price, and organizations designed to redistribute income through lobbying have an incentive to be minimum winning coalitions. Social barriers could not exist unless there were some groups capable of concerted action that had an interest in erecting them. We can see now that the special-interest organizations or collusions seeking advantage in either the market or the polity have precisely this interest.

In addition to controlling entry, the successful coalition must, we recall, have or generate a degree of consensus about its policies. The cartelistic coalition must also limit the output or labor of its own members; it must make all the members conform to some plan for restricting the amount sold, however much this limitation and conformity might limit innovation. As time goes on, custom and habit play a larger role. The special-interest organizations use their resources to argue that what they do is what in justice ought to be done. The more often pushy entrants and nonconforming innovators are repressed, the rarer they become, and what is not customary is “not done.”

Nothing about this process should make it work differently at different levels of income or social status. As Josiah Tucker remarked in the eighteenth century, “All men would be monopolists if they could.” This process may, however, proceed more rapidly in the professions, where public concern about unscrupulous or incompetent practitioners provides an ideal cover for policies that would in other contexts be described as monopoly or “greedy unionism.”21 The process takes place among the workers as well as the lords; some of the first craft unions were in fact organized in pubs.

There is a temptation to conclude dramatically that this involutional process has turned a nation of shopkeepers into a land of clubs and pubs. But this facile conclusion is too simple. Countervailing factors are also at work and may have greater quantitative significance. The rapid rate of scientific and technological advance in recent times has encouraged continuing reallocations of resources and brought about considerable occupational, social, and geographical mobility even in relatively sclerotic societies.22

In addition, there is another aspect of the process by which social status is transmitted to descendants that is relatively independent of the present theory. Prosperous and well-educated parents usually are able through education and upbringing to provide larger legacies of human as well as tangible capital to their children than are deprived families. Although apparently the children of high-ranking families occasionally are enfeebled by undemanding and overindulgent environments, or even neglected by parents obsessed with careers or personal concerns, there is every reason to suppose that, on average, the more successful families pass on the larger legacies of human and physical capital to their children. This presumably accounts for some of the modest correlation observed between the incomes and social positions of parents and those that their children eventually attain. The adoption of free public education and reasonably impartial scholarship systems in Britain in more recent times has disproportionately increased the amount of human capital passed on to children from poor families and thereby has tended to increase social mobility. Thus there are important aspects of social mobility that the theory offered in this book does not claim to explain and that can countervail those it does explain.

I must once again emphasize multiple causation and point out that there is no presumption that the process described in this book has brought increasing class consciousness, traditionalism, or antagonism to entrepreneurship. The contrary forces may overwhelm the involution even when no upheavals or invasions destroy the institutions that sustain it. The only hypothesis on this point that can reasonably be derived from the theory is that, of two societies that were in other respects equal, the one with the longer history of stability, security, and freedom of association would have more institutions that limit entry and innovation, that these institutions would encourage more social interaction and homogeneity among their members, and that what is said and done by these institutions would have at least some influence on what people in that society find customary and fitting.23

The evidence that has already been presented is sufficient to provoke some readers to ask rhetorically what the policy implications of the argument might be and to answer that a country ought to seek a revolution, or even provoke a war in which it would be defeated. Of course, this policy recommendation makes no more (or less) sense than the suggestion that one ought to welcome pestilence as a cure for overpopulation. In addition to being silly, the rhetorical recommendation obscures the true principal policy implications of the logic that has been developed here (which will be discussed later). Those readers who believe that the main policy implication of the present theory is that a nation should casually engage in revolutions or unsuccessful wars should read the remaining chapters of the book, for some of the further implications of the logic that has already been set out are sure to surprise them.

This is really too early in the argument to consider policy implications. There is much more evidence to consider. Let us proceed, as the lovely expression used by Mao Tse Tung’s more pragmatic successors says, “to seek truth from facts,” and to do so without the preconceptions that a prior knowledge of policy implications sometimes can generate. Let us look first at the other developed democracies that, although lacking as long a history of stability and immunity from invasion as Britain, have nonetheless enjoyed relatively long periods of stability and security—namely, Switzerland, Sweden, and the United States.

As a glance at table 1.1 reveals, Switzerland has been one of the slowest growing of the developed democracies in the postwar period; it has grown more slowly than Great Britain. Such slow growth in a long-stable country certainly is consistent with the theory. We should not, however, jump to the conclusion that Switzerland necessarily corroborates the argument I have offered, because Switzerland for some time has had a higher per capita income than most other European countries and therefore has enjoyed less “catch-up” growth. Those countries that had relatively low per capita incomes in the early postwar period presumably had more opportunities to grow than Switzerland had, so probably we should make an honorary addition to Switzerland’s growth rate to obtain a fairer comparison. Even though no one knows just what size this honorary addition should be, possibly it would be large enough to classify Switzerland as having a relatively successful postwar growth performance. This is, in effect, the assumption made in “Pressure Politics and Economic Growth: Olson’s Theory and the Swiss Experience” by Franz Lehner,24 a native of Switzerland who is a professor of political science at the University of Bochum in Germany. Lehner shows that the exceptionally restrictive constitutional arrangements in Switzerland make it extremely difficult to pass new legislation. This makes it difficult for lobbies to get their way and thus greatly limits Switzerland’s losses from special-interest legislation. The high per capita income that the Swiss have achieved is then, by Lehner’s argument, evidence in favor of the present theory.

Since cartelistic action sometimes requires government enforcement, the Swiss constitutional limitations undoubtedly also limit the losses from cartelization. On the other hand, there can also be cartelistic action without government connivance, and so I would hypothesize that Switzerland ought to have accumulated some degree of cartelistic organization. The extraordinary Swiss reliance on guest workers from other countries for a considerable period would suggest that this cartelization mainly would not involve the unskilled or semi-skilled manual workers that are strongly unionized in some other countries, but rather business enterprises and the professions. The theory here also would predict that, by now, stable Switzerland would have acquired at least a few rigidities in its social structure. The private cartelization and some attendant class stratification should have offset to at least a slight extent some of the growth Switzerland has enjoyed from the limitations on the predations of lobbies and governmentally enforced cartels. Another consideration is that Switzerland has enjoyed not only the normal encouragement for long-run investment that stability provides but also the special gains that accrue from its history as a haven of stability and its permissive banking laws in a historically unstable and restrictive continent. Just as Las Vegas and Monaco profit more from gambling than they would if similar gambling were legal everywhere, so Switzerland has profited more from its stability and permissiveness than it would have if its neighbors had enjoyed a similar tranquility and liberalism. If there had not been capital flights and fears about the stability and economic controls of other continental countries, Switzerland would not have received so much capital or had such an impressive role in international banking. Of course, this factor must not be exaggerated; Britain has profited from being a center of international finance for much the same reasons. When all these factors, and another factor that will emerge in a later chapter, are taken into account, it is difficult to be utterly certain how the theory fares in the test against Swiss experience. The hope must be that the example of Lehner’s useful study will stimulate additional expert investigations of the matter.

If we also make a large enough honorary addition to Sweden’s growth rate to adjust for its relatively high per capita income, that country then seems at first sight to contradict the theory. Although it industrialized late, Sweden has enjoyed freedom of organization and immunity from invasion for a long time, and it does not have the constitutional obstacles to the passage of special-interest legislation that Switzerland has. The strength and coverage of special-interest organizations in Sweden are what our model would predict. Why then did Sweden (at some times during the postwar period, at least) achieve respectable growth even though it already had a high standard of living? In particular, why (despite some severe recent reverses) has Sweden’s economic performance been superior to Britain’s when its special-interest organizations are also uncommonly strong? Similarly, why has neighboring Norway done as well as it has? Even though Norway’s stability was interrupted briefly by Nazi occupation during World War II, it has relatively strong special-interest organizations. Does the experience of these two countries argue against our theory?

Not at all. The theory lets us see this experience from a new perspective. As we recall from chapter 3, the basic logic of the theory implies that encompassing organizations face very different incentives than do narrow special-interest organizations (Implication 5). Sufficiently encompassing or inclusive special-interest organizations will internalize much of the cost of inefficient policies and accordingly have an incentive to redistribute income to themselves with the least possible social cost, and to give some weight to economic growth and to the interests of society as a whole. Sweden’s and Norway’s main special-interest organizations are highly encompassing, especially in comparison with those in Great Britain and the United States, and probably are more encompassing than those in any other developed democracies. For most of the postwar period, for example, practically all unionized manual workers in each of these countries have belonged to one great labor organization. The employers’ organizations are similarly inclusive. As our theory predicts, Swedish labor leaders, at least, at times have been distinguished from their counterparts in many other countries by their advocacy of various growth-increasing policies, such as subsidies to labor mobility and retraining rather than subsidies to maintain employment in unprofitable firms, and by their tolerance of market forces.25 Organized business in Sweden and Norway has apparently sought and certainly obtained fewer tariffs than its counterparts in many other developed countries. It is even conceivable that the partial integration for part of the postwar period of the Norwegian and Swedish labor organizations with the even more encompassing labor parties (on a basis that contrasts with corresponding situations in Great Britain) has at times accentuated the incentive to protect efficiency and growth,26 although any definite statement here must await further research.

Why Sweden and Norway have especially encompassing organizations also needs to be explained. This task will in part be left for another publication,27 but one hypothesis follows immediately from my basic theory: smaller groups are much more likely to organize spontaneously than large ones (Implication 3). This suggests that many relatively small special-interest organizations (for example, British and American craft unions) would be a legacy of early industrialization,28 whereas special-interest organizations that are established later, partly in emulation of the experience of countries that had previously industrialized, could be as large as their sponsors or promoters could make them.29 The improvement over time in transportation and communication and in the skills needed for large-scale organization could also make it feasible to organize larger organizations in more recent than in earlier times. Small and relatively homogeneous societies obviously would be more likely to have organizations that are relatively encompassing in relation to the society than would large and diverse societies.

It might seem that the gains from encompassing—as compared with narrow special-interest—organizations would ensure that there would be a tendency for such organizations to merge in every society, in much the way large firms come to dominate those industries in which large-scale production is most efficient. This is not necessarily the case. When there are large economies of scale, the owners of small firms usually can get more money by selling out to or merging with a larger firm and thereby can capture some of the gains from creating a firm of a more efficient scale. The leaders of a special-interest organization, by contrast, cannot get any of the gains that might result from the mergers that could create a more encompassing organization by “selling” their organization; a merger is indeed even likely to result in the elimination or demotion of some of the relevant leaders. There is, accordingly, no inexorable tendency for encompassing organizations to replace narrow ones.

Inclusive special-interest organizations, however, sometimes can bireak apart. There are significant conflicts of interest in any large group in any society. For example, these arise among firms in different indus-tr ies or situations over government policies that harm some firms while helping others, or between strategically placed or powerful groups of w orkers and groups of workers with less independent bargaining power when uniform wage increases (or diminished wage differentials) are sought by an encompassing union.

As the discussion of Implication 5 pointed out, the extent to which a special-interest organization is encompassing affects the incentives it faces when seeking redistributions to its clients and when deciding whether to seek improvements in the efficiency of the society; but the link between incentives and policies is not perfect. A special-interest organization’s leaders may be mistaken about what policies will best serve their clients; they may not immediately see the gains their clients will obtain from more rapid economic growth, for example, or may be mistaken about what policies will achieve such growth. Since, as chapter 2 pointed out, information about collective goods is itself a collective good, the chances of mistakes about such matters are perhaps greater than they are for firms or individuals dealing with private goods. And even if most of the firms in a market make mistaken decisions, one or more may make correct ones and these will accordingly profit, expand, and be imitated, so the errors before very long will be corrected. In a society with encompassing special-interest organizations, by contrast, there are not many entities making choices, and these may be sui generis organizations without direct competitors, so there may be no corrective mechanism apart from the reaction to the setbacks the society suffers. Thus there is no guarantee that encompassing organizations will always operate in ways consistent with the well-being of their societies, or that the societies with such organizations will necessarily always prosper.

Nonetheless, the society with encompassing special-interest organizations does have institutions that have some incentive to take the interest of society into account, so there is the possibility and perhaps the presumption that these institutions in fact generally do so. Sweden and Norway (and sometimes other countries, such as Austria) at times have been the beneficiaries of such behavior. There is not even the possibility that such behavior can be general among the narrow special-interest organizations and collusions that prevail in some other countries.

Since it achieved its independence, the United States has never been occupied by a foreign power. It has lived under the same democratic constitution for nearly two hundred years. Its special-interest organizations, moreover, are possibly less encompassing in relation to the economy as a whole than those in any other country. The United States has also been since World War II one of the slowest growing of the developed democracies.

In view of these facts, it is tempting to conclude that the experience of the United States provides additional evidence for the theory offered here. This conclusion is, however, premature, and probably also too simple. Different parts of the United States were settled at very different times, and thus some have had a much longer time to accumulate special-interest organizations than others. Some parts of the United States have enjoyed political stability and security from invasion for almost two centuries. By contrast, the South was not only defeated and devastated in the Civil War—and then subjected to federal occupation and “carpet-bagging”—but for a century had no definitive outcome to the struggle over racial policy that had been an ultimate cause of that war.

There are other complications that make it more difficult to see how well aggregate U.S. experience fits the theory offered here. The United States, like the other societies of recent settlement, has no direct legacy from the Middle Ages. The feudal pattern that seems to have left less of a mark on the chaotic Continent than on stable Britain has never even existed in the United States, or in most of the other societies settled in postmedieval times. Few of the earliest immigrants from Britain to the thirteen colonies were people of high social status, and it was often impossible to enforce feudal patterns of subordination, or to enforce contracts with indentured servants, on a frontier that sometimes offered a better livelihood to those who abandoned their masters. The social and cultural consequences of the non-feudal origins of American society were presumably enhanced by the relatively egalitarian initial distribution of income and wealth (except, of course, in the areas with slavery), which in turn must have owed something to the abundance of unused land. A vast variety of foreign observers, of whom Tocqueville is the best known, testified to this greater equality, and there is quantitative evidence as well that the inequality of wealth was less in the American colonies than in Britain.30 This point has not been seriously disputed by historians (though there has been a good deal of disagreement about the timing and extent of the apparent increase in inequality sometime during the nineteenth century and about the estimates showing some reduction in inequality since the late 1920s).31 The implication of the absence of a direct feudal inheritance and the unusually egalitarian beginnings of much of American society, according to the model developed earlier, is that the United States (and any areas of recent settlement with similar origins) should be predicted to be less class-conscious and less condescending toward business pursuits than are societies with a direct feudal inheritance, or at any event less than those with a feudal tradition and a long history of institutional stability.

Obviously, the United States and comparable countries can have no special-interest organizations or institutions with medieval origins. The theory predicts that countries that were settled after the medieval period, and that have enjoyed substantial periods of stability and immunity from invasion, would more nearly resemble Great Britain in their labor unions and in modern types of lobbying organizations than in any structural or cultural characteristics that had had medieval origins. It would also suggest that, other things being equal, the societies of recent settlement would have levels of income or rates of growth at least a trifle above those that would be predicted using only the length of time they had enjoyed political stability and immunity from invasion.

Just as it is hard to say exactly what growth performance the theory offered here would predict for the United States, so it is also difficult to say exactly how bad or good the country’s growth performance has been. In at least most of the postwar period, the United States has had the highest per capita income of all major nations, partly because (at least in the earlier decades) it had a higher level of technology than other countries. This means that, at least for part of the postwar period, other countries have had the opportunity to catch up by adopting superior technologies used for some time in the United States, as well as the opportunity to adopt those developed in the current period, whereas in most industries in the United States any technical improvements could be only of the latter variety. Thus the U.S. growth rate should probably be adjusted upward for a fair test of the model offered here, but no one knows by just how much.

The very fact that the United States is a large federation composed of different states, often with different histories and policies, makes it possible to test the theory against the experience of the separate states.

It is indeed doubly fortunate that such a test is possible, because it helps compensate for the fact there are only a handful of developed democracies with distinctive growth rates. As we shall see later, the theory offered here explains at least the most strikingly anomalous growth rates among the developed democracies, and no competing theory developed so far can do this. Although this is an important argument in favor of the present theory, my impression is that many readers of early drafts of the argument have been too easily convinced by it. Intellectual history tells us that there is a considerable susceptibility to new theories when the old ones are manifestly inadequate, and this is as it should be. Yet, just as it is understandable that a drowning man should grab at a straw, so it is also unhelpful. We should look skeptically at the theory offered here, however it may compare with the available alternatives. This skepticism is all the more important because of the aforementioned small number of developed democracies with distinctive growth rates. When the number of observations or data points is so small, it is always possible that the relative growth rates are what they are because of a series of special circumstances, and that these special circumstances have, simply by chance, produced a configuration of results that is in accord with what the theory predicts. The timing and gradual emergence of Britain’s relatively low ranking in growth rates is somewhat reassuring, because special circumstances are unlikely to have generated the particular profile of relative growth rates observed over such a long period. So are MurreH’s results in his comparison of old and new British and West German industries; since he compared so many industries, his results are almost certainly not due to chance. Nonetheless, there are so many ways in which the facts can mislead us that it is important to remain skeptical and to be thankful for the additional observations that can be obtained from the separate states (and from the other countries and developments to be considered in later chapters).

The number of observations is emphasized partly because it is so often neglected. It is neglected both by those who draw strong generalizations out of a few observations (for example, those who write of the ‘'lessons” drawn from only one or two historical experiences), and also by those whose beliefs remain unaltered by even massive statistical evidence (for example, those who still doubt the compelling statistical evidence on the harmful effects of smoking). If prior reactions to earlier drafts are any guide, this book will probably illustrate both problems—a small number of dramatic illustrations will generate more belief in the theory than is warranted, whereas the statistical evidence will generate less conviction than it should. Psychologists have also shown through experiments that vivid or dramatic examples tend to be given more weight as evidence than they deserve, whereas extensive statistical evidence tends to be given less credence than is justified.32

Admittedly, one reason why statistical arguments sometimes fail to persuade is that different statistical methods may produce varying results, and investigators are suspected of choosing the method most favorable to their arguments. The range of statistical techniques available to the modern econometrician is so wide that the zealous advocate can often ‘'torture the data until it confesses.” But I will in the following tests use only the most obvious and elementary procedures. A rudimentary approach is appropriate as a first step and also offers the reader a small degree of protection against the selection of methods favorable to the theory offered here.

Although the statistical methods that will be used are among the simplest, they may still seem forbidding to those readers who have never studied the principles of statistical inference. Partly in the interest of those readers, and partly to provide a guide to the statistical material that follows, I shall endeavor in the next three paragraphs to offer a glimpse of the statistical tests and findings in everyday language.

The theory here cannot say very much about state-to-state variations in economic growth in earlier periods of American history. One reason is that, until more recent times, even the oldest states had not been settled long enough to accumulate a great deal of special-interest organization, so such organizations could not have caused large variations in growth rates across states. Another reason is that until fairly recently the United States had frontier areas that were growing unusually rapidly, and it would bias any tests in favor of the theory offered here if the rapid growth of these frontier areas were attributed solely, or even mainly, to their lack of distributional coalitions; through most of American history the newer, more westerly areas have tended to grow more rapidly, and the center of gravity of the American economy has moved steadily in a westerly and southwesterly direction. This is entirely consistent with the theory but is due partly to other factors. Accordingly, the theory is most appropriately tested against recent experience; the following tests consider the period since World War II, and most often the period since the mid-1960s.

The statistical tests reveal that throughout the postwar period, and especially since the early 1960s, there has been a strong and systematic relationship between the length of time a state has been settled and its rate of growth of both per capita and total income. The relationship is negative—the longer a state has been settled and the longer the time it has had to accumulate special-interest groups, the slower its rate of growth. In the formerly Confederate states, the development of many types of special-interest groups has been severely limited by defeat in the Civil War, reconstruction, and racial turmoil and discrimination (which, until recently, practically ruled out black or racially integrated groups). The theory predicts that these states should accordingly be growing more rapidly than other states, and the statistical tests systematically and strongly confirm that this is the case. The theory also predicts that the recently settled states and those that suffered defeat and turmoil should have relatively less membership in special-interest organizations, and although comprehensive data on state-by-state membership in such organizations have not been found, the most pertinent available data again strongly support the theory. Moreover, as expected, the higher the rate of special-interest organization membership, the lower the rate of growth. All of the many statistical tests showed that the relationships are not only always in the expected direction, but virtually without exception were statistically significant as well. The statistical significance means that the results almost certainly are not due to chance, but it does not rule out the possibility that some obscure factor that happens to be correlated with the predictions of the theory could have made the results spurious. There is an independent tendency for relatively poorer states to catch up with relatively more prosperous ones, but the hypothesized relationships hold even when this tendency is taken into account. A variety of tests with other familiar or plausible hypotheses about regional growth show that these other hypotheses do not explain the data nearly as well as the present theory. Strongly significant as the statistical tests are, it is nonetheless clear that many other factors also importantly influence the relative rates of growth of different states. Accordingly, the theory here is not nearly sufficient to serve as a general explanation of differences in regional growth rates. There is also a need for massive historical and statistical studies (especially on the South) that would search for heretofore unrecognized sources of variation in regional growth rates and then take them into account along with the present theory. Only then could we rule out the possibility that there are obscure but systematic factors that somehow have happened to generate the pattern of results that the theory leads one to expect.

It is possible to follow the remaining chapters of this book even if one skips the rest of this chapter, but I hope that even readers who have never studied statistical inference will persevere. They will rarely find easier or more straightforward examples of statistical tests. And the evidence is important; it is not simply the experience of one country, but of forty-eight separate jurisdictions, each of which provides additional evidence.

The statistics we are about to consider lend themselves especially well to straightforward treatment. The theory specifies a connection that goes primarily or entirely in one direction: the length of time an area has had stability should affect its rate of growth, but there is (for a first approximation) not much reason to suppose that the rate of growth of a region would on the whole greatly change the rate at which it accumulates distributional coalitions. On the one hand, a booming economy may make strikes and barriers to entry more advantageous, but on the other, adversity can give a threatened group a reason to organize to protect customary levels of income. This suggests that simple and straightforward tests (nonstructural regressions) should not only be sufficient, but perhaps even better than any more subtle method (such as a simultaneous equation specification) apparent now.

Since the theory predicts that the longer an area has had stable freedom of organization the more growth-retarding organizations it will accumulate, states that have been settled and politically organized the longest ought, other things being equal, to have the lowest rates of growth, except when defeat in war and instability such as occurred in the ex-Confederate states destroyed such organizations. The length of time a state has been settled and politically organized can roughly be measured by the number of years it has enjoyed statehood. Thus, if we exclude erstwhile members of the Confederacy, a simple regression between years since statehood and rates of growth should provide a preliminary test of our model.

If carried back into the nineteenth century, however, this test might be biased in favor of the model, since some states were then still being settled. The westward-moving frontier must have created disequilibria (the California gold rush might be the most dramatic example) with unusual rates of growth of total, if not per capita, income. The frontier is generally supposed to have disappeared by the end of the nineteenth century, but where agriculture and other industries oriented to natural resources are at issue, some disequilibria may have persisted into the present century. Thus, the more recent the period, the more likely that frontier effects are no longer present. In large part for this reason, we begin by looking at the years since 1965. Great disequilibria are unlikely three-quarters of a century after the frontier closed, especially since many of the great agricultural areas in most recently settled states suffered substantial exogenous depopulations during the agricultural depression of the 1920s, the dust bowl of the 1930s, and the massive postwar migration from farms to cities. The two newest states may, however, still be enjoying frontier or similar disequilibria and thus bias the results in favor of the theory, so we shall consider only the forty-eight contiguous states.

Another reason for concentrating on relatively recent experience arises from the ease of mobility of capital and labor within the United States. If the theory offered here is correct, there ought to be some migration of both firms and workers from those states with more distributional coalitions to those with fewer. The extent of this migration should be given by the extent of the differential in the degree of special-interest organization across states. There could not have been any substantial differential in the earliest periods of American history, but if the theory is right there should be significant differentials in more recent times. This will be explored more specifically later, but it is already evident that the states which the theory predicts should grow most rapidly should do so in periods when the differential in levels of special-interest organization across states is greatest.

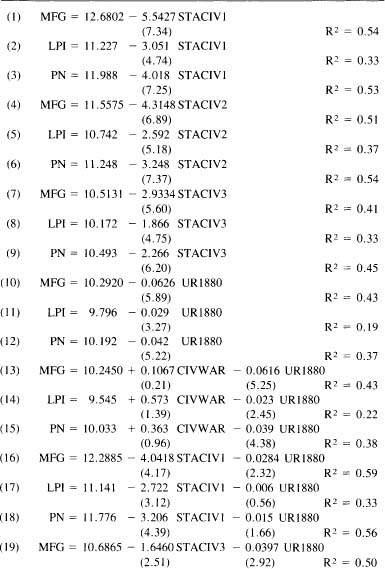

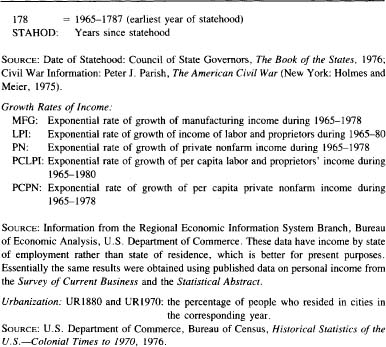

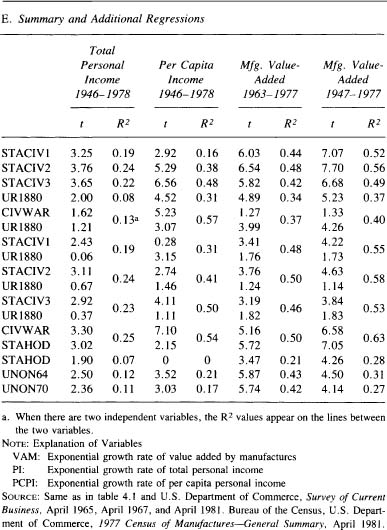

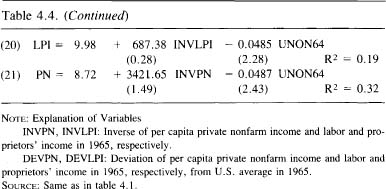

The aforementioned regressions and a variety of other statistical tests were done with my former student Kwang Choi, who has undertaken more detailed inquiries that complement the present study, and are to be published separately.33 We found that there is the hypothesized negative relationship between the number of years since statehood for all non-Confederate states and their current rates of economic growth, and that this relationship is statistically significant. This holds true for income from manufacturing only, for private nonfarm income, for personal income, and for labor and proprietors’ income from all sources.*

In a country with no barriers to migration of workers, migration should eventually make real per capita incomes much the same everywhere, so the regressions use measures of total rather than per capita income as dependent variables. When the corresponding measures of growth of per capita income by state are used, however, the relationship remains negative and statistically significant.** Conceivably, the duration of statehood and political stability should not be measured on a ratio scale, and nonparametric tests focusing only on rank orders should be used instead, to guard against the possibility that the result might be an artifact of states at the far ends of the distribution or of other spurious intervals. Accordingly, Choi ran nonparametric tests on the same variables, and these equally supported the hypothesis derived from the theory.34

Happily, there is a separate test that can provide not only additional evidence but also insight into whether it is the duration of stable freedom of organization and collusion, rather than any lingering frontier effect, that explains the results. Several of the defeated Confederate states were among the original thirteen colonies, so they are as far from frontier status as any parts of the United States, and, of course, all the Confederate states had achieved statehood by 1860. Yet the political stability of these Deep South states was profoundly interrupted by the Civil War and its aftermath, and even at times by conflicts and uncertainties about racial policies that were settled only with the civil rights and voting rights acts of 1964 and 1965. If the model proposed here is correct, the former Confederate states should have growth rates more akin to those of the newer western states than to the older northeastern states. Although we shall soon turn to earlier periods, we shall start with the southern rates of growth since 1965. In earlier years there were episodes of instability, lynchings, and other lawlessness that complicate the picture, but after the passage of the voting rights and civil rights acts there was clearly a definitive answer to the question of whether the South could have significantly different racial policies than the rest of the nation and unambiguous stability. In earlier years there is also the greater danger of the lingering frontier effects even in the South, so including it will not serve so well as protection against the possibility of these effects in the West; there is also a lesser differential in special-interest accumulation across states, not to mention other complexities. So we briefly postpone our consideration of earlier periods and ask if the former Confederate states have a higher average growth rate than the other states in the years since 1965.

They definitely do. The exponential growth rate for the ex-Confederate states is 9.37 percent for income from labor and proprietorships (LPI), and 9.55 percent for private nonfarm income (PN), whereas the corresponding figures are 8.12 percent and 8.19 percent for the thirty-seven states that were not in the Confederacy. If variations in growth rates are normally distributed, the probabilities that these two samples are from different populations can be calculated. Choi found that the difference in growth rates on this basis was statistically significant. A nonparametric test, the Mann-Whitney U-test, also indicated that the difference in average growth rates between the South and the rest of the United States was statistically significant. Again, this result holds true whether the growth of total or per capita income is at issue. These findings obviously argue in favor of the model offered in this book and should also allay any fears that regression results involving years since statehood for the non-Confederate states were due to any western frontier settlement that might have taken place since 1965.

Because the southern and western results are essentially the same and the parametric and nonparametric tests yield about the same results, it is reasonable to consider the data on all the forty-eight states together and use only standard ordinary-least-squares regression techniques. This has been done with the few score of Choi’s regressions shown in the following tables. Although more elaborate tests might possibly produce different conclusions, the results are nonetheless remarkably clear and consistent.

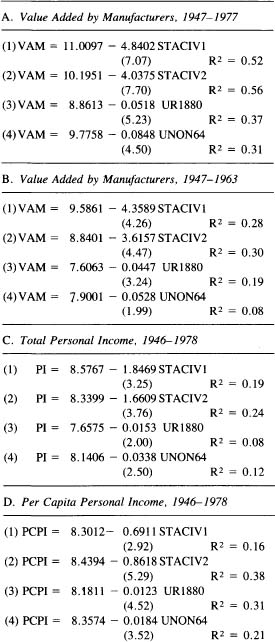

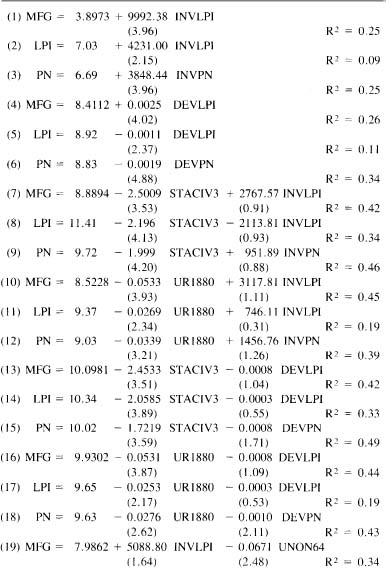

As the results with the separate treatment of the South and the other states suggest, any regressions that use the year of statehood for the non-Confederate states to establish the earliest possible date for special-interest groups, and any year after the end of the Civil War to establish when the Confederate states came to have stable freedom of organization, will provide a statistically significant explanation of growth rates by state (table 4.1). Since organizations that could most directly constrain modern urban and industrial life have had more time to develop in states that have been urbanized longer, the level of urbanization in 1880 was also used as an independent variable. This variable again tends to have a significant negative influence on current growth rates. In combination with a dummy variable for defeat in the Civil War, it explains a fair amount of the variance, but it is apparently not as significant as the duration of freedom of organization. The same patterns hold for income from manufacturing, and for all of our broader measures of income as well, and apply whether total or per capita income is at issue.

The theory predicts that distributional coalitions should be more powerful in places that have had stable freedom of organization, so we can get an additional test of its validity by looking at the spatial distribution of the memberships of such organizations. The only special-interest organizations on which we have so far found state-by-state membership statistics are labor unions. In view of the widespread neglect of the parallels between labor unions and other special-interest organizations, it is important not to attribute all the losses caused by such organizations and collusions to labor unions. They are, however, certainly the most relevant organizations for studying income from manufacturing, and for reasons that will be explained later are appropriate for tests within a country in which manufacturers are free to move to wherever costs of production are lowest. In addition, many other types of distributional coalitions, such as trade associations of manufacturers, are likely to obtain special-interest legislation or monopoly prices that can enrich the states in which they are located at the expense of the rest of the nation. Thus labor unions are the main organizations with negative effects on local growth, and their membership should also serve as a proxy measure of the strength of such other coalitions that are harmful to local growth.35 We will nonetheless also consider the number of lawyers per 100,000 of population, on the debatable assumption that the need for lawyers would probably show some tendency to increase with the extent of lobbying and the complexity of legislation and regulation it brings about.

Table 4.1. Determinants of Growth since 1965

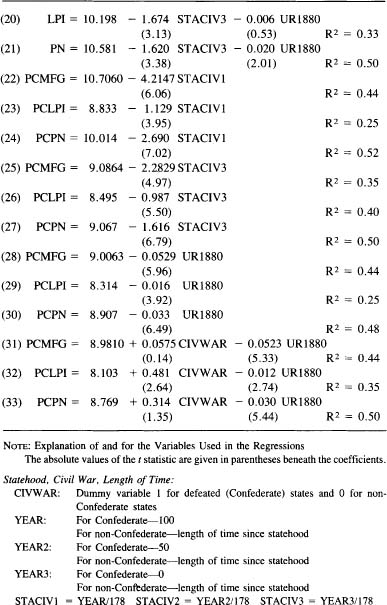

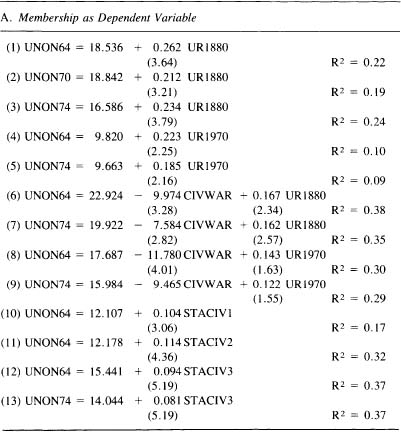

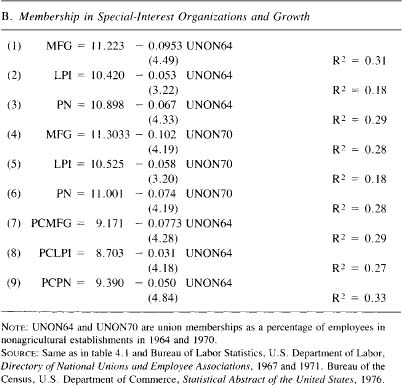

Table 4.2 suggests immediately that union membership as a percentage of nonagricultural employment is greatest in the states that have had stable freedom of organization longest. Urbanization in 1880 is also a statistically significant predictor of union membership in the period from 1964 on. Indeed, the crucial importance of the duration of freedom of organization is shown by the fact that urbanization in the 1880s is a better predictor of union membership in the 1960s and 1970s than urbanization in 1970. The number of years of freedom of organization is often an even better predictor. There is a similar connection between the length of time a state has enjoyed political stability and the number of lawyers, although this relationship is less strong and sometimes not statistically significant.

Table 4.2. Special Interest Organizations A. Membership as Dependent Variable

As the previous results and the theory suggest, there is also a statistically significant negative relationship between special-interest organization membership in 1964 and 1970 and rates of economic growth since 1965. This result holds for income from manufacturing and for all measures of income and for both total and per capita changes in those measures (table 4.2, part b). Thus there is not only statistically significant evidence of the connection between the duration of stable freedom of organization and growth rates predicted by our model, but also (at least as far as labor unions are concerned) distinct and statistically significant evidence that the process the model predicts is going on, that is, that the accumulation of special-interest organization is occurring, and that such organizations do, on balance, have the hypothesized negative effect on economic growth. A negative relationship between the proportion of lawyers and the rate of growth also is evident, but again this relationship is somewhat weaker.

A number of possible problems should be considered. One of these is that changing responses to climate may explain the results. The advances in airconditioning presumably have induced migration toward some of the more rapidly growing states (although other rapidly growing states in the Northwest are among the coldest in the country). Accordingly, Choi regressed the mean temperature for January for each state’s principal city, and also the average temperature in the city over the entire year, against growth rates by state. These variables were positively correlated with growth rates, but usually less strongly than our measures of the length of time a state has had to acquire distributional coalitions.

Another possibility is that the rapidly growing states happened to contain the industries that have been growing most rapidly, and that such an accident of location explains our results. To test for this possibility, Choi regressed the rate of growth of ten major (one-digit) industries, and also a subclassification (two-digit) of eighteen manufacturing industries that existed in more than a score of states, against our measure of the time available in each state for the formation of special-interest groups. In all these industries but one (agricultural services, forestry, and fisheries), all or almost all of the signs were consistent with the theory, and in a large proportion of cases the results for each separate industry were statistically significant as well.36

A third possible problem is that the forty-eight states might be, for the purposes of the present argument, essentially three homogeneous regions—the South, the West, and the Northeast-Midwest. If that is true, we do not have forty-eight observations but only three, and thus too few for statistically significant results. To test for this possibility, Choi and I examined each of the three regions separately and also considered the thirty-seven non-Confederate states as a separate unit. The same pattern shows up within each region; the pattern is weak within the West and to some extent in the ex-Confederate states but very strong within the Northeast-Midwest region and for the thirty-seven non-Confederate states.

Still another possibility is that the results are a peculiarity of the recent past and considering a longer period would give different results. If we take the longest possible period, the whole of American history, we see a massive movement in a westerly (even somewhat southwesterly) direction. This movement has been greatly slowed at times by the rapid relative decline in agriculture (which abated only in the 1970s), but its existence and continued rapid pace long after the disappearance of the frontier is consistent with the theory.

The picture in the South over the longer run, although it also appears in a general way consistent with the theory, is more complex and more difficult to sort out. If my highly preliminary investigation of southern history is at all correct, the first important special-interest coalitions that emerged in the South during and after Reconstruction were small, local, and white-only coalitions, sometimes without formal organization. All these small groups were by no means always against the advancement of the black population, but many were, and there was an undoubted susceptibility of the majority of the white southern population at that time to racist demagogues. The much weaker black population was in essence denied political organization and often the opportunity to vote through extra-legal coercion, which included at times widespread lynchings. The electoral consequence of the disproportion in organized power between the races and the susceptibility of the white population to racist appeals was the gradual emergence of the “Jim Crow” pattern of legalized segregation and racial subordination. This was apparently augmented by informal exclusion and repression by some of the white-only coalitions. Many have supposed that the segregationist patterns in the South emerged promptly after Reconstruction or even earlier, but the historian C. Vann Woodward has shown that decades passed before most of the Jim Crow legislation was passed and that it was in the twentieth century that this system reached its full severity.37 In other words, the collective action of the white supremacists took some time to emerge in each of the many southern communities and states.

The low productivity of black sharecroppers predates the full development of the Jim Crow system and cannot be blamed entirely upon it. The causes of this low productivity and the widespread poverty of the black population after the Civil War are the subject of a vast and controversy-laden literature that this book could by no means resolve. Yet it is not on the surface astonishing that the deprivations of the black population under slavery, their lack of education and limited access to credit, and the vast and sudden change from the large-scale slave-plantation to small-scale independent sharecropping should have resulted in low productivity in black agriculture, and that this should have had adverse effects on the southern economy as a whole.

The lack of industrial development is another matter. Although I must postpone any conclusions for a separate publication that may emerge from some further research that I hope to do,38 my very tentative hunch now is that many of the organized interests in many of the southern communities realized that any substantial outside investment or in-migration from the North would disrupt or at least endanger the Jim Crow system and the lattice of vested interests intertwined with it. There certainly was a lot of intensely agrarian, chauvinistic, anti-industrial, and anti-capitalist rhetoric for a long time in the South.39 The large-scale, efforts to attract business from afar, moreover, emerged mainly after the old system was already breaking down. Outside investors and potential in-migrants must at times also have been put off by the extra-legal violence and the uncertain stability of the system. The old pattern of coalitions in the South was eventually emasculated by New Deal and postwar federal policies, by cosmopolitan influences due to better communication and transportation, by increased black resistance, by adaptation to new technologies and methods of production, and perhaps by still other factors. These changes and a variety of favorable exogenous developments permitted rapid change and growth. A new pattern of coalitions, such as racially integrated labor unions, has begun to form in the South, but this new pattern of coalitions has been emerging only gradually, and thus has not had any massively adverse impact on economic development.