and Foreign Trade

| 5 |  |

Jurisdiccional Integration and Foreign Trade |

As we know from table 1.1, the original six members of the European Economic Community have grown rapidly since World War II, particularly in comparison with Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and for some of the member countries the growth was fastest in the 1960s when the Common Market was becoming operational. Although I have offered some explanation of the most anomalous or puzzling cases of rapid growth in Germany and France, there has been no analysis of the rapid growth of the other four members of the Six. Such an analysis is necessary not only to complete the coverage of the developed democracies, but also to show that there was a further factor contributing to the growth of France and Germany that complements the explanation in the previous chapter. In addition, the analysis of the Common Market will also help us to understand why New Zealand’s postwar growth performance has been about as poor as that of the United Kingdom, and why Australia’s growth has also been unimpressive, especially in view of the valuable natural resources it has discovered in the postwar period.

Looking at the timing of the growth of most of the Six, one is tempted to conclude, as many casual observers have, that the Common Market was responsible. This is post hoc ergo propter hoc reasoning and we obviously cannot rely on it, especially in view of the fact that most, if not all, of the careful quantitative studies indicate that the gains from the Common Market were very small in relation to the increases in income that the members enjoyed. The quantitative studies of the gains from freer trade, like those of the losses from monopoly, usually show far smaller effects than economists anticipated, and the calculations of the gains from the Common Market fit the normal pattern. The studies of Edwin Truman and Mordechai Kreinen, for example, while maintaining that trade creation overwhelmed any trade diversion, imply that the Common Market added 2 percent or less to EEC manufacturing consumption.1 Bela Balassa, moreover, argues that, taking economies of scale as well as other sources of gain from the Common Market into account, there was a “0.3 percentage point rise in the ratio of the annual increment of trade to that of GNP,” which was probably “accompanied by a one-tenth of one percentage point increase in the growth rate. By 1965 the cumulative effect of the Common Market’s establishment on the Gross National Product of the member countries would thus have reached one-half of one percent of GNP.”2 Careful studies by other skilled economists also suggest that the intuitive judgment that large customs unions can bring about substantial increases in the rate of growth is not supported by economists’ typical comparative-static calculations.

There is a hint that there is more to the matter in the instances of remarkable economic growth in historical times discussed in chapter 1. The United States, we know, became the world’s leading economy in the century or so after the adoption of its constitution. Germany similarly advanced from its status as a poor area in the first half of the nineteenth century to the point where it was, by the start of World War I, overtaking Britain, and this occurred after the formation of the Zollverein, or customs union, of most German-speaking areas and the political unification of Germany. Both situations, I shall argue, were similar to the Common Market because they shared three crucial features. These common features are sometimes overlooked because the conventional nomenclature calls attention to the differences between the formation of governments and of customs unions.

The Common Market created a large area within which there was something approaching free trade; it allowed relatively unrestricted movement of labor, capital, and firms within this larger area; and it shifted the authority for decisions about tariffs and certain other matters from the capitals of each of the six nations to the European Economic Community as a whole. When we consider these features, we immediately recognize that the creation of a new or larger country out of many smaller jurisdictions also includes each of these three fundamental features.

The establishment of the United States of America out of thirteen independent ex-colonies involved the creation of an area of free trade and factor mobility, as well as a shift in the institutions that made some of the governmental decisions. The adoption of the Constitution did, in fact, remove tariffs that New York had established against certain imports from Connecticut and New Jersey. Similarly, not only the Zollverein but also the creation of the German Reich itself included the same essential features. Until well into the nineteenth century, most of the German-speaking areas of Europe were separate principalities or city-states or other small jurisdictions with their own tariffs, barriers to mobility, and economic policies, but an expanding common market and a shift of some governmental powers resulted from the Zollverein, and even more from the formation of the German state, which was complete by 1871.

There was a much earlier development elsewhere in Europe that also created vastly larger markets, established far wider domains for factor mobility, and shifted the locus of governmental decision-making. The centralizing monarchs of England and France in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries tried to create nation-states out of the existing mosaic of parochial feudal fiefdoms; there had been nominal national kingdoms before, but the real power customarily rested with lords of various fiefs, or sometimes with virtually self-governing walled towns. Each of these mini-governments tended to have its own tolls and tariffs; a boat trip along the Rhine, where toll-collecting castles are sometimes only about a kilometer apart, is sufficient to remind one how numerous were local tolls in medieval Europe. The nationalizing monarchs, with their mercantilistic policies, strove to eliminate these local authorities and their restrictions and in turn imposed highly protectionist policies at the national level. In France many of the feudal tolls and restrictions to trade and factor mobility were not removed until the Revolution, but in Britain the creation of nationwide markets took place much more rapidly. Whether there was any causal connection or not, we know that the creation of effective national jurisdictions in Western Europe was followed by the commercial revolution, and in Britain ultimately by the Industrial Revolution.

In many respects, and possibly the most important ones, the creation of meaningful national governments is very different from the creation of customs unions, however effective the customs union might be. Nonetheless, in all the cases we have considered, a much wider area of relatively free trade was established, a similarly wide area of relatively free movement of factors of production was created, and the power to make at least some important decisions about economic policy was shifted to a new institution in a new location. There was in each case a considerable measure of what I shall call here jurisdictional integration. It would be much better if we could avoid coining a new phrase, especially such a ponderous one, but the familiar labels obscure the common features that concern us here.

Since there are several cases of jurisdictional integration followed by fairly rapid economic progress, it is now even more tempting to posit a causal connection. That would still be premature. For one thing, we should have some idea just how jurisdictional integration would bring about rapid growth, and statistical studies such as those cited above for the Common Market suggest that the gains from the freer trade are not nearly large enough to explain substantial economic growth. For another, the number of cases of jurisdictional integration is still not large enough to allow confident generalization. We must therefore look at the specific patterns of growth within jurisdictions as well as across them to see if they provide corroborating evidence. In addition, we must present a theoretical model that could explain why jurisdictional integration should have the observed effects.

One of the most remarkable and consistent patterns in the advancing economies of the West in the early modern period was the relative (and sometimes absolute) decline of many of what used to be the major cities. This decline of the major cities is paradoxical, for the single most important development moving the West ahead was surely the Industrial Revolution, and Western society today is probably more urbanized than any society in history. The commercial and industrial revolutions created new cities, or made great cities out of mere villages, instead of building upon the base of the larger existing medieval and early modern cities. Major capitals like London and Paris grew, of course, as administrative centers and as consumers of part of the new wealth, but they were by no means the sources of the growth. As the French economic historian Fernand Braudel pointed out, “The towns were an example of deep-seated disequilibrium, asymmetrical growth, and irrational and unproductive investment on a nationwide scale…. These enormous urban formations are more linked to the past, to accomplished evolutions, faults and weaknesses of the societies and economies of the Ancien Regime, than to preparations for the future…. The obvious fact was that the capital cities would be present at the forthcoming industrial revolution in the role of spectators. Not London, but Manchester, Leeds, Glasgow, and innumerable small proletarian towns launched the new era.”3

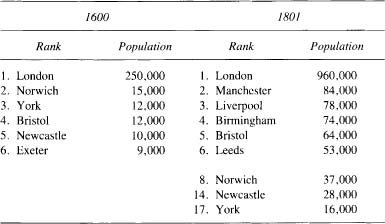

M. J. Daunton shows that, at least for Great Britain during the Industrial Revolution, Braudel was right. Of the six cities deemed to have been the largest in England in 1600, only Bristol, a port that profited from the economic growth, and London were among the top six in 1801. Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham, and Leeds completed the list in 1801. York, the third largest city in 1600, was the seventeenth in 1801; Newcastle, the fifth largest city in 1600, was the fourteenth in 1801, as indicated by table 5.1.4

Even before 1601 there was concern about the “desolation of cytes and tounes.” Charles Pythian-Adams’s essay on “Urban Decay in Late Medieval England” argues from a mass of detailed, if scattered, figures and contemporary comments that the population and income of many English cities had begun to decline before the Black Death. Though Pythian-Adams finds that the decline of certain cities may be offset by the expansion of others, we are left wondering why so many towns declined while others grew. During the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, and especially between 1520 and 1570, Pythian-Adams finds that most of the more important towns were “under pressure,” if not in an “acute urban crisis,” often involving significant loss of economic activity and population.5

On the Continent, towns were not so likely to be substantially autonomous institutions operating within relatively stable national boundaries. Partly becausexof this, and partly because the Continent did not experience the rapid changes of the Industrial Revolution until later, the situation there is not so striking. Nonetheless, there were many similar replacements of older urban centers with newer towns or rural industry. One example is the partial shift of the medieval woolen industry from the cities of Flanders to nearby Brabant and the decline of Flemish woolen production generally in relation to that of the North Italian cities, which in their turn declined as well. Another is the decline of Naples, on the eve of the French Revolution probably Europe’s fourth largest city. Domenico Sella concludes that ‘'throughout Europe, none of the old centers of early capitalism (whether Antwerp or Venice, Amsterdam or Genoa, Bordeaux or Florence) played a leading role in the advent of modern industrialization.” In seventeenth-century Spanish Lombardy, whose economy Sella studied in great detail, he finds that the cities “had few of the traits that we associate with modern industrialization and in fact some that were diametrically opposed to it…. The cities were thus clearly ill-suited to serve as the cradle of large-scale industrialization; far from being the vanguard of the modern economy, they must be viewed as anachronistic relics of a rapidly fading past. To find the harbingers of the modern economy, it is to the countryside that we must turn.”6 It was also commonplace that suburbs should grow at the expense of central cities.7 A classic case is the decline of the central city of Aachen, which Herbert Kisch has chronicled in detail.8

Table 5.1. English Cities Ranked by Size

Medieval towns and cities were small by modern standards. Their boundaries usually were precisely defined by city walls and they often had a substantial degree of autonomy (and in some cases were indepen dent of any larger government). Within these small jurisdictions there would be only a few merchants in any one line of commerce and only a limited number of skilled craftsmen in any one specialized craft, even if the population of the town was in the thousands. The primitive methods of transportation and the absence of safe and passable national road systems also tended to segment markets; a handful of merchants or skilled craftsmen could more easily secure a monopoly if they could cartelize local production. When the merchants in a given line of commerce had more wealth than the townspeople generally, it seems likely that they would have interacted with one another more often than with those of lesser means. To some extent, this also would have been true of skilled craftsmen.

The logic set out in chapter 2 implies that small groups have far greater opportunities to organize for collective action than large ones and suggests that, if other things are equal, there will be relatively more organization in small jurisdictions than in large ones. The logic also implies that small and homogeneous groups that interact socially also have the further advantage that social selective incentives will help them to organize for collective action. These considerations entailed Implication 3, that small groups are better and sooner organized than large ones. If the logic set out earlier was correct, it follows that the merchants in a given line of commerce and practitioners of particular skilled crafts in a medieval city would be especially well placed to organize collective action. If the city contained even a few thousand people, it is unlikely that the population as a whole could organize to counter such combinations, although in tiny villages the population would be small enough for this to occur.

The result of these favorable conditions for collective cartelistic action was, of course, the guilds. The guilds naturally endeavored to augment the advantages of their small numbers and social homogeneity with coercive civic power as well, and many of them did indeed influence, if not control, the towns in which they operated. This outcome was particularly likely in medieval England, where the national monarchies found it expedient to grant towns a substantial degree of autonomy. In what is now Germany, guilds would more often confront small principalities more jealous of their power and would need to work out symbiotic relationships with territorial rulers and the nobility. In France, especially, guilds would often be given monopoly privileges in return for special tax payments, in part because of the cost of wars and the limits on tax collections due to the administrative shortcomings of government. The city-states of North Italy extended well beyond the walls of the town, and in such cases the guilds would have a wider sphere of control if they shared power, but at the same time they were thereby exposed to instabilities in the North Italian environment that must sometimes have interrupted their development or curtailed their powers. In spite of all the variation from region to region, guilds of merchants and master craftsmen, and occasionally journeymen, became commonplace from Byzantium in the East to Britain in the West, and from the Hanse-atic cities in the North to Italy in the South.

Although they provided insurance and social benefits for their members, the guilds were, above all, distributional coalitions that used monopoly power and often political power to serve their interests. As Implications 4 and 7 predicted, they also reduced economic efficiency and delayed technological innovation. The use of apprenticeship to control entry is demonstrated conclusively by the requirement in some guilds that a journeyman could become a master only upon the payment of a fee, by the rule in some guilds that apprentices and journeymen could not marry, and by the stipulation in other guilds that the son of a master need not serve the apprenticeship that was normally required. The myriad rules intended to keep one master from advancing significantly at the expense of others undoubtedly limited innovation. (Since masters owned capital and employed journeymen and apprentices, it is important not to confuse guilds of masters, or those of merchants, with labor unions—they usually are better regarded as business cartels.)

What should be expected when there is jurisdictional integration in an environment of relatively autonomous cities with a dense network of guilds? Implication 2 indicated that the accumulation of special-interest organization occurs gradually in stable societies with unchanged borders. If the area over which trade can occur without tolls or restrictions is made much larger, a guild or any similar cartel will find that it controls only a small part of the total market. A monopoly of a small part of an integrated market is, of course, not a monopoly at all: people will not pay a monopoly price to a guild member if they can buy at a lower price from those outside the cartel. There is free movement of the factors of production within the integrated jurisdiction, providing an incentive for sellers to move into any community in the jurisdiction in which cartelization has brought higher prices. Jurisdictional integration also means that the political decisions are now made by different people in a different institutional setting at a location probably quite some distance away. In addition, the amount of political influence required to change the policy of the integrated jurisdiction will be vastly larger than the amount that was needed in the previous, relatively parochial jurisdictions. Sometimes the gains from jurisdictional integration were partly offset when financially pressed monarchs sold monopoly rights to guilds in return for special taxes, but in general the guilds lost both monopoly power and political influence when economically integrated, nationwide jurisdictions replaced local jurisdictions.

The level of transportation costs is also significant. If transportation costs are too high to make it worthwhile to transport a given product from one town to another, the jurisdictional integration should be less significant, even though there would still be a tendency for competing sellers to migrate to the cartelized locations in the integrated jurisdiction. The time of the commercial revolution was also a time of improved transportation, especially over water, which led to the development of new routes to Asia and the discovery of the New World. The growth in the power of central government also reduced the danger of travel from community to community by gradually eliminating the anarchic conflict among feudal lords and the extent of lawlessness in rural areas, and it brought road building and eventually the construction of canals. If the countryside is relatively safe from violence, not only is transportation cheaper but production may also take place wherever costs are lowest.

When jurisdictional integration occurs, new special-interest groups matching the scale of the larger jurisdiction will not immediately spring up, because, as we know from Implication 2, such coalitions emerge only gradually in stable situations. It will not, however, take small groups as long to organize as large ones (Implication 3). The great merchants involved in larger-scale trade, often over longer distances, were among the first groups to organize or collude on a national scale. They were often extremely successful; as Adam Smith pointed out, the influence of the “merchants” gave the great governments of Europe the policy of “mercantilism,” which favored influential merchants and their allies at the expense of the rest of the nation. Often this involved severely protectionist policies that protected the influential merchants from foreign competitors—mercantilism is, to this day, nearly synonymous with protectionism.

It might seem, then, that the gains from jurisdictional integration in early modern Europe were brief and unimportant, since the mercantilist policies followed close on the heels of the decaying guilds in the towns. Not so. The reason is that tariffs and restrictions around a sizable nation are incomparably less serious than tariffs and restrictions around each town or fiefdom. Much of the trade will be zVtfnznational, whether the nation has tariffs at its borders or not, because of transport costs and the natural diversity of any large country. Restrictions at national borders do not have any direct effect on this trade, whereas trade restrictions around each town and fiefdom reduce or eliminate most of it. Moreover, as Adam Smith pointed out, “the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market,” and thus the widening markets of the period of jurisdictional integration also made it possible to take advantage of economies of scale and specialization. Another way of thinking of the matter emerges when we realize that the shift of trade restrictions from a community level to a national level reduces the length of tariff barriers by a vast multiple. I believe the greatest reductions of trade restrictions in history have come from reducing the mileage rather than the height of trade restrictions.

Since the commercial and the industrial revolutions took place during and after the extraordinary reduction in trade barriers and other guild restrictions and occurred overwhelmingly in new cities and suburbs relatively free of guilds, there appears to have been a causal connection. Yet both the timing of growth and the fact that guilds were regularly at the locations where the growth was obstructed could conceivably have been coincidences. Happily, there are additional aspects of the pattern of growth which suggest that this was not the case.

One of these is the “putting out system” in the textile industry, which was then the most important manufacturing industry. Under this remarkable system, merchants would travel all over the countryside to “put out” to individual families material that was to be spun or woven and then return at a later time to pick up the yarn or cloth. Clearly such a system required a lot of time, travel, and transaction costs. There were uncertainties about how much material had been left with each family and how much yarn or cloth could be made from it, and these uncertainties provoked haggling and disputes. The merchant also had the risk that the material he had put out would be stolen. Given the obvious disadvantages, we must ask why this system was used. The answer from any number of accounts is that this system, despite its disadvantages, was cheaper than production in towns controlled by guilds. There may have been some advantages of production scattered throughout the countryside, such as cheaper food for the workers, but this could not explain the tendency at the same time for production to expand in suburbs around the towns controlled by guilds. (Adam Smith said that “if you would have your work tolerably executed, it must be done in the suburbs, where the workmen have no exclusive privilege, having nothing but their character to depend upon, and you must then smuggle it into town as well as you can.”)9 Neither can any possible inherent advantages of manufacturing in scattered rural sites explain the objections of guilds to the production in the countryside; Flemish guilds, for example; even sent expeditions into the countryside to destroy the equipment of those to whom materials had been put out.

By and large there was more economic growth in the areas of early modern Europe with jurisdictional integration than in the areas with parochial restrictions, and the greatest growth in the areas that had experienced political upheaval as well as jurisdictional integration. Centralized government came early to England; it was the first nation to succeed in establishing a nationwide market relatively free of local trade restrictions. Though comprehensive quantitative evidence is lacking, the commercial revolution was by most accounts stronger in that country than in any other country except the Dutch Republic. In the seventeenth century, and even to an extent in the early eighteenth century, Britain suffered from civil war and political instability.10 Undoubtedly the instability brought some destruction and waste and, in addition, discouraged long-run investment. But within a few decades after it became clear that stable and nationwide government had been re-established in Britain, the Industrial Revolution was under way. It is also generally accepted that there was much less restriction of enterprise of trade in mid-eighteenth century Britain than on most of the Continent, and for the most part probably better transportation as well.

Similarly, the Dutch economy enjoyed its Golden Age, and reached much the highest levels of development in seventeenth-century Europe, just after the United Provinces of the Netherlands succeeded in their struggle for independence from Spain. At least some guilds that had been strong in the Spanish period were emasculated, and guilds were not strong in most of the activities that were important to Dutch international trade.11 As a lowland coastal nation with many canals and rivers, the Dutch enjoyed unusually easy transportation.

France apparently enjoyed very much less economic unification than did Great Britain; it did not eliminate many of its medieval trade restrictions until the French Revolution. Yet France did enjoy some jurisdictional integration well before the Revolution. Most notably under Louis XIV and Colbert, there was some economic unification and improvement of transportation. At the same time, Louis XIV, short of money for wars and other dissipations, often gave monopoly rights to guilds in return for special taxes, and a powerful special-interest group, the nobility, was generally able to avoid being taxed. Notwithstanding Colbert’s tariff reforms, goods from some provinces of France were treated as though they came from foreign countries. Still, within the cinq grosses fermes, or five large tax farms, at least, there was a measure of unification; this area had a population as large as or larger than that of England. Thus France probably did not have as much parochial restriction of trade as the totally Balkanized German-speaking and Italian-speaking areas of Europe, and its economic performance also appears to have been better than that in those areas, however far short it fell of the Dutch and British achievement.12 It was not until the second half of the nineteenth century that the German-speaking and Italian-speaking areas enjoyed much jurisdictional integration, and when that occurred these areas, and particularly Germany, also enjoyed substantial economic growth.

Of course, thousands of other factors were important in explaining the varying fortunes of the different parts of Europe, so it would be preposterous to offer the present argument as a monocausal explanation. It is, nonetheless, remarkable how well the theory fits the pattern of growth across different nations as well as the pattern of growth within countries.

In the United States, there was not only the constitutional provision mentioned earlier that prohibited separate states from imposing barriers to trade and factor mobility, but also more than a century of westward expansion. Any cartel or lobby in the United States before the present century had to face the fact that substantial new areas were regularly being added to the country. Competition could always come from these new areas, notwithstanding the high tariffs at the national level, and the new areas also increased the size of the polity, so that ever-larger coalitions would be needed either for cartelization or lobbying. Vast immigration also worked against cartelization of the labor market. In addition, the United States, like all frontier areas, could begin without a legacy of distributional coalitions and rigid social classes. In view of all these factors, the extraordinary achievement of the U.S. economy for a century and more after the adoption of the Constitution is not surprising.

The case with which we began, the rapid growth in the 1960s of the six nations that created the Common Market, also fits the pattern. The three largest of these countries—France, Germany, and Italy—had suffered a great deal of instability and invasion. This implied that they had relatively fewer special-interest organizations than they would otherwise have had, and often also more encompassing organizations. In France and Italy the labor unions did not have the resources or strength for sustained industrial action; in Germany the union structure growing out of the occupation was highly encompassing.

As Implication 3 tells us, small groups can organize more quickly and thoroughly than large groups, so even in the countries that had suffered the most turbulence those industries that had small numbers of large firms were likely to be organized. In Italy the Allied occupation had not been as thorough as it was elsewhere, and some industries remained organized from fascist times. In all the countries, organizations of substantial firms, which were often manufacturing firms, would frequently have an incentive to seek protection through tariffs, quotas, or other controls for their industry, and in at least some of these countries they were very likely to get it. Once imports could be excluded, the home market could also be profitably cartelized; as an old American adage tells us, “The tariff is the Mother of the Trust/’13 If foreign firms should seek to enter the country to compete with the domestic firms, the latter could play upon nationalistic sentiments to obtain exclusionary or discriminatory legislation against the multinationals. Sometimes, in some countries such as postwar Germany at the time of Ludwig Erhard, there would, because of economic ideology or the interests of exporters, be some determined resistance to protectionist pressures, but in other countries like France and Italy in the years just before the creation of the Common Market the capacity or the inclination to resist these pressures was lacking.

In France and Italy and to some extent in most of the other countries, the coalitional structure and government policy insured that tariffs, quotas, exchange controls, and restrictions on foreign firms were the principal threat to economic efficiency. In France, for example, as Jean-Frangois Hennart argues in “The Political Economy of Comparative Growth Rates: The Case of France,”14 exchange controls, quotas, and licenses had nearly closed off the French market from foreign competition; raw materials were often allocated by trade associations, and trade and professional associations fixed prices and allocated production in many important sectors. In such situations the losses from protectionism and the cartelization it facilitates could hardly have been small. If a Common Market could put the power to determine the level of protection and to set the rules about factor mobility and entry of foreign firms out of the reach of each nation’s colluding firms, the economies in question could be relatively efficient. The smaller nations among the Six were different in several respects, but they would also gain greatly from freer trade, in part because their small size made protectionist policies more costly for them. Most of the founding members of the European Economic Community (EEC), then, were countries with coalitional structures, protectionist policies, or small sizes that made the Common Market especially useful to them. This would not so clearly have been the case if the Common Market had chosen very high tariff levels against the outside world, but the important Kennedy Round of tariff cuts insured that that did not happen.

It does not follow that every country that joins any institution called a common market will enjoy gains comparable to those obtained by most of the Six. Whether a nation gains from a customs union depends on many factors, including its prior levels of protection and (to a lesser extent) those of the customs union it joins. In the case of France and Italy, for example, the Common Market almost certainly meant more liberal policies for trade and factor mobility than these countries otherwise would have had. In the case of Great Britain, where the interests of organized exporters and the international financial community in the City of London have long been significant, the level of protection was perhaps not so high, and it is not obvious that joining the Common Market on balance liberalized British trade. When many high-tariff jurisdictions merge there is normally a great reduction in tariff barriers, even if the integrated jurisdiction has equally high tariffs, but a country with low tariffs already is getting most of the attainable gains from trade.

The coalitional structure of a society also makes a difference. In Britain the professions, government employees, and many firms (such as “High Street” or downtown retail merchants) that would have no foreign competition in any case are well-organized; joining the Common Market could not significantly undermine their organizations through freer trade, although a shift of decision-making to a larger jurisdiction could reduce their lobbying power. More foreign competition for manufacturing firms can reduce the power of unions, since manufacturers whose labor costs are far out of line must either cut back production or hold out for lower labor costs, but even here the influence is indirect and presumably not as significant as when imports directly undermine a cartel of manufacturing firms.

Common markets have even been tried in or proposed for developing countries with comparative advantage in the same goods and thus little reason to trade with one another, but this cannot promote growth. For these and other reasons, it is not possible to say whether a customs union will be good for a country’s growth. One has to look at the prior level of protectionism, the coalitional structure, the potential gains from trade among the members, and still other factors in each individual case.

The growth rates of Australia and New Zealand, we recall, were not greatly different from those of Britain. In spite of the exceptional endowments of natural resources in relation to population that these two countries possess, their levels of per capita income lately have fallen behind those of many crowded and resource-poor countries in Western Europe. If we examine the tariff levels of Australia and New Zealand in the spirit of the foregoing analysis of jurisdictional integration, and remember that these countries have also had relatively long histories of political stability and immunity from invasion, we obtain a new explanation of their poor growth performance.

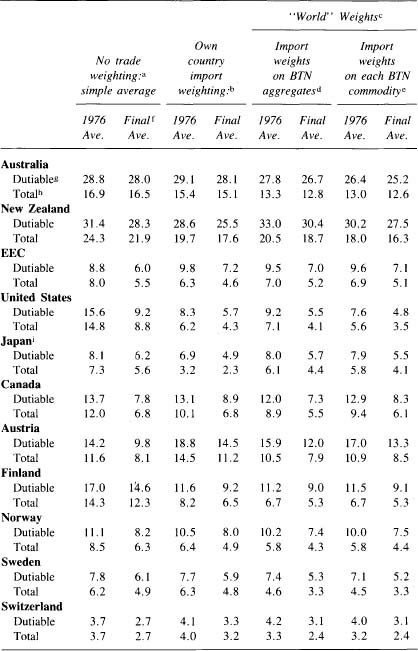

There are problems in calculating average tariff levels for different countries. Tariffs on important commodities should receive greater weight than tariffs on minor commodities, but the importance of each commodity for a country cannot be determined by the amount of its imports, since the country would not import much of any commodity, however important, if its tariff against that commodity were sufficiently high. Fortunately, there have been some calculations of average tariff levels that determine the weight to be attributed to the tariff on each commodity by the magnitude of the trade in this commodity among all countries that are important in world trade. The latest such calculations that I have been able to find were prepared by the Office of the United States Trade Representative. These calculations have not previously been published; they are shown in the columns labeled ‘ ‘World Weights” in table 5.2. Unfortunately, the average tariff levels given in the table probably underestimate the true level of protection, for they take no account of quotas and other nontariff barriers and are based on what international trade theorists call the nominal rather than the effective rate of protection. The table is nonetheless an approximate guide to relative levels of protection on industrial products in the different countries. One reason is that nontariff barriers are generated by the same organizational and political forces as tariffs and in the developed nations, at least, seem to vary across countries in similar ways. It is probably also significant that the different types of calculations listed in different columns of table 5.2 show broadly similar results, as do earlier calculations by other institutions.

Table 5.2 shows that Australia and New Zealand—especially New Zealand—have far higher tariffs than any of the other countries described. Their levels of protection are two to three times the level in the EEC and the United States and four to five times as high as those of Sweden and Switzerland. As might be expected from the level of its tariffs, quotas on imports are also unusually important in New Zealand. The impact of protection levels that are uniquely high by the standards of the developed democracies is made even greater by the small size of Austrialian and New Zealand economies; larger economies such as those of the United States or Japan would not lose nearly as much per capita from the same level of protection as Australia and New Zealand do.

The theory offered in this book suggests that manufacturing firms and urban interests in Australia and New Zealand would have organized to seek protection. When this protection was attained, they would some times have been able to engage in oligopolistic or cartelistic practices that would not have been feasible with free trade. With high tariffs and limitations on domestic competition, firms could survive even if they paid more than competitive wages, so there was more scope for labor unions and greater gains from monopolizing labor than otherwise. Restrictions on Asian immigration would further facilitate cartelization of labor. Stability and immunity from invasion would ensure that few special-interest organizations would be eliminated, but more would be organized as time went on (Implication 2). The result would be that frontiers initially free of cartels and lobbies would eventually become highly organized, and economies that initially had exceptionally high per capita incomes would eventually fall behind the income levels of European countries with incomparably lower ratios of natural resources to population. There is a need for detailed studies of the histories of Australia and New Zealand from this theoretical perspective. The histories of these countries, like any others, are undoubtedly complicated and no mono-causal explanation will do. Final judgment should wait for the specialized research. But preliminary investigation into Australia and New Zealand suggests that the theory fits these countries like a pair of gloves.

A comparison with Australia and New Zealand puts the British economy in a more favorable light. The less restrictive trade policies that Great Britain has followed, presumably because of the importance of the organized power of industrial exporters and its free trade inheritance from the nineteenth century, probably mean that parts of its economy are open to more competition than corresponding sectors in Australia or New Zealand, notwithstanding Britain’s still longer history of stability. Australia, like Britain, is an industrialized country with the overwhelming proportion of its work force in cities. But how many readers in competitive markets outside Australia and its environs have ever purchased an Australian manufactured product? Transport costs from Australia to the United States and Europe are high, but so are they high from Japan. Australia probably does not have comparative advantage in many kinds of manufactures, so we might not see many Australian manufactured goods even if Australia had different trade policies. Nonetheless, with a large part of Australia’s healthy and well-educated population devoted to the production of a wide range of manufactured products, the paucity of sales of manufactures abroad is evidence of a serious misallocation of resources. British manufacturing exports, by contrast, are fairly common, although of diminishing relative significance. Social manifestations of distributional coalitions, on the other hand, are more serious in Britain, with its inheritance from feudal times, than in Australia or New Zealand.

Table 5.2. Average Industrial Tariff Levels

SOURCE: Dr. Harvey Bale, Office of the United States Trade Representative.

a. An average of tariff levels on the assumption that all commodities are of equal significance.

b. The relative weight attributed to each tariff is given by the imports of that commodity by that country.

c. The significance of each tariff determined by world imports of the commodity, or aggregate of commodities, to which the tariff applies. World imports are the imports of the countries listed and the EEC.

d. “BTN” means Brussels Tariff Nomenclature. The weight attributed to each tariff is given by the world imports of the BTN class of commodities in which it falls.

e. Each tariff weighted by world imports of that particular commodity—the maximum attainable disaggregation.

f. “Final” means after the Tokyo Round of tariff reductions.

g. Average tariff rates considering only those commodities on which tariffs are levied. h. Average tariff levels of duty-free commodities as well as those to which duties apply.

i. Some anecdotal evidence, as well as casual impressions of the relatively high costs that Japanese consumers must pay for many imported goods, and the fact that agriculture tariffs are not included raise the question whether these figures may give the impression that the level of protection is lower than it actually is. This is a matter in need of further research.

The present argument also casts additional light on some other variations in economic performance. Consider Sweden and Switzerland, which have enjoyed somewhat higher per capita incomes than most European countries. As table 5.2 reveals, Sweden and Switzerland, and especially the latter, have had unusually low levels of protection. Note also that the Japanese economy grew more rapidly in the 1960s than in the 1950s, despite the fact that Japan could gain more from catching up by borrowing foreign technology in the earlier decade than the later. As Alfred Ho emphasizes in Japan s Trade Liberalization in the 1960's,15 between 1960 and 1965 the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) ‘'liberalization rate” measure for Japan improved from 41 percent to 93 percent. Finally, note that Germany, which considerably liberalized its economic policies before entering the Common Market, grew more rapidly in the 1950s than in the 1960s, in contrast to EEC partners like Belgium, France, and the Netherlands. Although again I want to emphasize that many different causes are normally involved, it is certainly not difficult to find instances in which freer trade is associated with growth and prosperity.

The paradox arising from the frequent association of freer trade (whether obtained through jurisdictional integration or by cutting tariff levels) and faster growth, and the skillful calculations suggesting that the gains from trade creation are relatively small, remains. Indeed, since we now have a wider array of cases where freer trade is associated with more rapid growth and several aspects of the patterns of growth suggest that the freer trade is connected with the growth, the paradox is heightened. If freer trade leads to more rapid growth, why does it not show up in the measures of the gains from the transactions that the trade liberalization allows to take place?

The reason is that there is a further advantage of freer trade that escapes the usual comparative-static measurements. It escapes these measurements because the gains are not direct gains of those who take part in the international transactions that the liberalization permitted, but other gains from increases in efficiency in the importing country— increases that are distinct from and additional to any that arise because of comparative advantage.

In the interest of readers who are not economists, it may be helpful to point out that the conventional case for freeing trade rests on the theory of comparative advantage. This theory goes back at least to David Ricardo, one of the giants on whose shoulders the economist is fortunate to stand. The theory of comparative advantage is lucidly and rigorously stated in many excellent textbooks, so there is no need here to go into it, or into certain exceptional circumstances that could make tariffs possibly advantageous. The literature on comparative advantage is so valuable and fascinating that it ought to be part of everyone’s education. Only one point in that rich literature, however, is indispensable to what follows. This is the point that differences in costs of production drive the case for free trade because of comparative advantage. These differences are conventionally assumed to be due to differences in endowments of natural resources among countries, to the different proportions of other productive factors such as labor and capital in different economies, or to the economies of scale that sometimes result when different economies specialize in producing different products. If there is free trade among economies and transport costs are neglected, producers in each country will not produce a product if other countries with their different endowments of resources can produce it at lower cost. If each country produces only those goods it can produce at costs as low as or lower than those of other countries, there will be more production from the world’s resources. A country that protects domestic producers from the competition of imports gives its consumers an incentive to buy from more costly domestic producers, and more resources are consumed by these producers. These resources would, in general, yield more valued output for the country if they were devoted to activities in which the country has a comparative advantage and the proceeds were used to buy imports; normally with freer trade a country could have more of all goods, or at least more of some without less of any others.

The argument offered here is different from the conventional argument for comparative advantage, although resonant with that argument. To demonstrate that there are gains from freer trade that do not rest on comparative advantage or differences in cost of production, let us look first at the case of a country that has comparative advantage in the production of a good and exports that good, but that also is subject to the accumulation of distributional coalitions described in Implication 2. Suppose that the exporters who produce the good in question succeed in creating an organization with the power to lobby and to cartelize. It might seem that the exporters would have no interest in getting a tariff on the commodity they export, since their comparative advantage ensures that there will not be lower-cost imports from abroad in any case. In fact, exporters often do not seek tariffs. To illuminate the logic of the matter, and also to cover an important, if untypical, class of cases, we must note that they might gain from a tariff. With a tariff they may be able to sell what they sell on the home market at a higher price by shifting more of their output to the world market (where the elasticity of demand is usually greater), because they do not affect the world price that much (in other words, the organized exporters engage in price discrimination and thereby obtain more revenue than before). Even though the country had, and by assumption continues to have, comparative advantage in producing the good in question, eliminating the tariff will still increase efficiency. The reason is that the tariff is necessary to the socially inefficient two-price system that the organized exporters have arranged. This example is sufficient to show gains from freer trade that do not flow from the theory of comparative advantage or differences in costs across countries, but rather from the constraints that free trade and factor mobility impose on special-interest groups.

To explore a far more important aspect of this matter, assume that a number of countries have comparative advantage in the same types of production. Their natural resources and relative factor endowments are by stipulation exactly the same, and there are by assumption no economies of scale. Suppose that these countries for any reason have high levels of protection and that they have been stable for a long while. Then, by Implication 2, they would each have accumulated a dense network of coalitions. These coalitions would, by Implication 4, have an incentive to try to redistribute income to their clients rather than to increase the efficiency of the society. Because of Implications 6, 7, 8, and 9, they will entail slower decision-making, less mobility of resources, higher social barriers, more regulation, and slower growth for their societies.

Now suppose the tariffs between these identical countries are eliminated. Let us assume, in order to insure that we can handle the toughest conceivable case, that even the extent of distributional coalitions is identical in each of these countries, so there is no case for trade even on grounds of what I might call “institutional comparative advantage.” Even on these most difficult assumptions, however, the freeing of trade can make a vast contribution. We know from The Logic of Collective Action and from Implication 3 that it is more difficult to organize large groups than small ones. When there are no tariffs any cartel, to be effective, would have to include all the firms in all the countries in which production could take place (unless transport costs provide natural tariffs). So more firms or workers are needed to have an effective cartel. Differences of language and culture may also make international cartels more difficult to establish. With free trade among independent countries there is no way the coercive power of governments can be used to enforce the output restriction that cartels require. There is also no way to obtain special-interest legislation over the whole set of countries because there is no common government. Individual governments may still pass inefficient legislation for particular countries, but even this will be constrained if there is free movement of population and resources as well as free trade, since capital and labor will eventually move to jurisdictions with greater efficiency and higher incomes.

Given the difficulties of international cartelization, then, there will be for some time after the freeing of trade an opportunity for firms in each country to make a profit by selling in other countries at the high cartelized prices prevailing there. As firms—even if they continue to follow the cartel rules in their own country—undercut foreign cartels, all cartels fall. With the elimination of cartelization, the problems growing out of Implications 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9 diminish, efficiency improves, and the growth rate increases.

Economic theory, I have argued earlier, has been more like Newton’s mechanics than Darwin’s biology, and there is a need to add an evolutionary and historical approach. This also has been true of that part of economic theory called the theory of international trade. The traditional expositions of the theory of international trade that focus on the theory of comparative advantage are profound and valuable. The world would be a better place if they were more widely read. They also must be supplemented by theories of change over time of the kind that grew out of the analysis in chapter 3. The failure of the comparative-static calculations inspired by conventional theory to capture the increases in growth associated with freer trade is evidence that this is so.

In the last chapter the question arose of what the policy implications of the present argument might be. Some commentators on early drafts of the argument had suggested that its main policy implication was that there should be revolution or other forms of instability. Concerned that ideological preconceptions, both left-wing and right-wing, would distort our reading of the facts and the logic, I belittled that conclusion and promised readers who thought it was the main policy implication of my argument that they were in for some surprises. Now that a gentler and more conventional policy prescription is close at hand, it may not frighten most readers away from the rest of the book to say that, yes, if one happens to be delicately balancing the arguments for and against revolution, the theory here does shift the balance marginally in the revolutionary direction.

Consider the French Revolution. It brought about an appalling amount of bloodshed and destruction and introduced or exacerbated divisions in French political life that weakened and troubled France for many generations, perhaps even to the present day. At the same time, if the theory offered here is correct, the Revolution undoubtedly destroyed some outdated feudal restrictions, coalitions, and classes that made France less efficient. To say that the present theory adds marginally to the case for revolution, however, is for many readers in many societies similar to saying that an advantage of a dangerous sport like hang gliding is that it reduces the probability that one will die of a lingering and painful disease like cancer; the argument is true, but far from sufficient to change the choice of people who are in their right minds.

Now that we are all, I hope, reminded of the overwhelming importance of other considerations in most cases, it should not be misleading to point out that this ‘'revolutionary” implication of the present argument is not always of minor importance. We can now see more clearly that the contention of some conservatives that if social institutions have survived for a long time, they must necessarily be useful to the society, is wrong. We can also appreciate anew Thomas Jefferson’s observation that “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.”16 Let us now put this unduly dramatic matter aside and turn to a policy implication of vastly wider applicability.

The policy prescription is not in any way novel or revolutionary. Indeed, in keeping with my general emphasis on the contributions of my predecessors and professional colleagues, I would say that this policy recommendation has been shared by nearly every scholar of stature who has given the matter specialized thought. The recommendation unfortunately has far more often than not been ignored, and when it has been taken into account it almost always has been followed only to a limited degree. The policy implication, as readers of this chapter have long foreseen, is that there should be freer trade and fewer impediments to the free movement of factors of production and of firms.

Any readers who doubt that this policy recommendation has more often than not been ignored should note that most of the great examples of the freeing of trade and factor mobility have come about not because the recommendations of economists were followed, but wholly or largely as an incidental consequence of policies with other objectives. I have attempted to show in this chapter that the most notable reductions in barriers to the flow of products and productive factors have been reductions in the length rather than in the height of barriers—that they have resulted from jurisdictional integration. The jurisdictional integration brought about by the centralizing monarchs of early modern Europe was not inspired by liberal teaching, but by the monarchs’ lusts for power and pelf. The jurisdictional integration of the United States and Germany owed more to nationalistic, political, and military considerations than to economic understanding; the mainly inadvertent character of the massive liberalization these two countries brought about is proven by the tariffs, trusts, and cartels they accepted at a national level. Even the creation of the Common Market owed more to fears of Soviet imperialism, to a desire to insure that there would not be yet another Franco-German war, and to imitation of and uneasiness about the United States, than it did to a rigorous analysis of the gains from freer trade and factor mobility. Specialists have long known that a country could get most or all of the gains from freer trade without joining a customs union simply by reducing its own barriers unilaterally, and would indeed often gain much more from this than from joining a customs union. Unilateral tariff reductions are nonetheless rare.

Although the textbooks explain the other reasons for liberal or internationalist policies, such policies can draw additional support from the theory offered here, because free trade and factor movement evade and undercut distributional coalitions. If there is free international trade, there are international markets out of the control of any lobbies. The way in which free trade undermines cartelization of firms, and indirectly also reduces monopoly power in the labor market, has already been discussed. Free movement of productive factors and firms is no less subversive of distributional coalitions. If local entrepreneurs are free to sell equities without constraint to foreigners as well as to borrow abroad, those with less wealth or inferior connections at home will be better able to get the capital needed for competition with established firms, and may even be able to marshall enough resources to break into collusive oligopolies of large firms in industries where there are substantial economies of scale. If foreign or multinational firms are welcome to enter a country to produce and compete on an equal basis with local firms, they will not only often bring new ideas with them but also make the local market more competitive and perhaps destroy a cartel as well. That is one reason why they are usually so unpopular—the consumers who freely choose to buy their goods and the workers who choose to accept the new jobs they offer do not lose from the entry of the multinationals, but these consumers and workers may be persuaded that this foreign entry is undesirable by the propaganda of those who do.

The resistance to labor mobility across national borders has a similar inspiration. Whereas rapid and massive immigration obviously can generate social tensions and other costs, these costs are not the only reason for the barriers against foreign labor. The restrictions on immigration and guest workers in many countries and communities are promoted mainly by special-interest organizations representing the groups of workers who have to compete with the in-migrants; labor unions obtain limitations on the inflow of manual workers, medical societies impose stricter qualifying examinations for foreign-trained physicians, and so on. The separate states of the United States, for example, not only control admission into most professions, but often also into such diverse occupations as cosmetology, barbering, acupuncture, and lightning-rod salesmen. These controls are frequently used to keep out practitioners from other states. The nations of Western Europe also vary greatly in the proportion of migrants and guest workers they have admitted. Many other factors are involved, but the initial impression is that countries with weaker labor unions have accepted relatively larger inflows of labor.

The law of diminishing returns suggests that the growth of income per capita or per worker would be reduced when an already densely populated country imports more labor. However, as Charles Kindleberger has argued,17 the developed industrial economies in which per capita income has grown most rapidly are often those which have absorbed the most new labor. Kindleberger explains this in terms of Arthur Lewis’s famous model of growth with “unlimited supplies of labor,” and this hypothesis deserves careful study.

Another part of the explanation is that the size of the inflow of labor affects the strength of special-interest groups of workers. If a large pool of less expensive foreign labor may easily be tapped, and unions have significantly raised labor costs for domestic firms, then it will be profitable to set up new firms or establishments employing the outside labor. The competition of these new undertakings will in turn reduce the gains from monopoly over the labor force in the old establishments. Union co-optation of the outside workers will be at least delayed by cultural and linguistic differences or by the temporary status of guest workers. Similar freedom of entry for foreign professionals, of course, will undermine the cartelization that is characteristic of professions.

We are finally in a position to assess the ad hoc argument that Britain’s economic plight is due to its trade unions. This argument is in part profoundly wrong, and in part right and important. It is profoundly wrong because combinations of firms (being fewer in number) can and often do collude in their common interest more than larger numbers of employees can. The ad hoc anti-union argument also overlooks the professions, whose cartelization is generally older, and probably more costly to British society per person involved, than the average union. It also neglects the class structure and the anti-entrepreneurial and anti-business attitudes which grow in large part out of the same logic and history that underlie the British pattern of trade unions.

Despite its shortcomings, the blame-it-on-the-unions argument does have one important merit (if the professional associations are counted as unions). That arises because the net migration of labor into the United Kingdom has been relatively modest and was quickly restricted when it promised to become great (as was the case with Commonwealth immigrants from South Asia and the Caribbean). If we take a long-run or historical view, we can probably conclude that, relative to many other countries, Britain has not had especially high levels of protection or unusually restrictive legislation against foreign capital or multinational firms. Postwar multilateral tariff-cutting agreements, the Common Market, and falling transport costs have brought about a substantial increase in international trade. Thus many firms that export or that compete with importers are denied most of the gains from collusion, except in those cases where they have been able to form international cartels. The firms that provide international financial and insurance services in the City, for example, must be roughly as efficient as the foreigners with which they compete. This suggests that the British disease is most serious for goods and services and factors of production that do not face foreign competition and are at the same time in a situation where they are susceptible to organization for collective action. Those major “High Street” merchants who resist suburban shopping centers and hyper-markets, for example, can lobby and collude without any real fear that their customers will go overseas to shop. Thus relatively parochial industries and services, construction, government, the professions, and (as the ad hoc argument states) the unions probably account for a large share of the inefficiencies in the British economy. Since wages absorb most of the national income and much of British labor is organized, the unions also have great quantitative significance.

Unfortunately, as British experience in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries shows, free trade alone is not enough. Even in combination with free factor mobility it would not come close to being a panacea or complete solution. Freedom of trade and of factor mobility have to be used in combination with other policies to reduce or countervail cartelization and lobbying. But even with other policies, there are no total or permanent cures. This is because the distributional coalitions have the incentive and often also the power to prevent changes that would deprive them of their enlarged share of the social output. To borrow an evocative phrase from Marx, there is an ‘internal contradiction” in the development of stable societies. This is not the contradiction18 that Marx claimed to have found, but rather an inherent conflict between the colossal economic and political advantages of peace and stability and the longer-term losses that come from the accumulating networks of distributional coalitions that can survive only in stable environments.