Def Jam

Produced by Hank Shocklee and Chuck D

Released: April 1988

TRACKLISTING

01 Countdown to Armageddon

02 Bring the Noise

03 Don’t Believe the Hype

04 Cold Lampin’ with Flavor

05 Terminator X to the Edge of Panic

06 Mind Terrorist

07 Louder Than a Bomb

08 Caught, Can We Get a Witness?

09 Show ’Em Whatcha Got

10 She Watch Channel Zero?!

11 Night of the Living Baseheads

12 Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos

13 Security of the First World

14 Rebel Without a Pause

15 Prophets of Rage

16 Party for Your Right to Fight

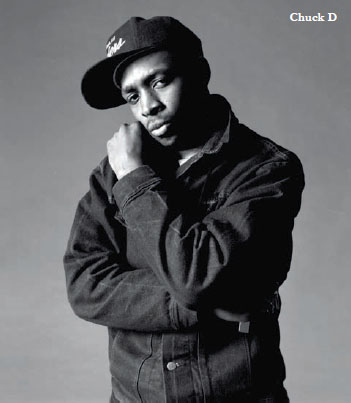

‘An important message should have its importance embedded into the way it’s relayed,’ Public Enemy’s architect and chief provocateur, rapper Chuck D once explained. ‘You hear Public Enemy, you hear a tone that says, “Look out! This is some serious shit coming!’’’

That was never more true than on the group’s incendiary second album, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back. Released in 1988, the record is a compelling, joyous overload of sound. It’s urgent, scary and provocative, yet also thrillingly catchy and fastidiously assembled. It was a landmark release for hip-hop, a political statement that spoke in languages old and new, and once you’d heard it it was apparent that the world looked, and sounded, different from what you’d previously known.

It Takes a Nation of Millions appeared about a decade after hip-hop had first found a public profile, making it the equivalent of Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, which arrived roughly 10 years after the dawning of rock & roll. Both albums took everything in their field that had preceded them and then reinterpreted it with new influences and outcomes. They were aware of history and its truths, but also defied it in the name of creating a new reality.

Or as Chuck D – the D rightly stands for ‘dangerous’ – puts it on ‘Don’t Believe the Hype’, ‘The book of the new school rap game/Writers treat me like Coltrane, insane/Yes to them, but to me I’m a different kind/We’re brothers of the same mind, unblind/Caught in the middle/And not surrenderin’/I don’t rhyme for the sake of riddlin’.’

With Public Enemy, speed – and the sense of unstoppable momentum it engendered – was the key. Their songs often rocked at a ferociously fast beats-per-minute rate, daring you at once to keep up mentally and not to physically stand still, and it was the same with their career. They’d been together little more than two years when they released their second album, having been custom built by Chuck D once he was signed to Def Jam Records by Bill Stephney – the former Program Director at New York state college radio station WBAU, where Chuck D (Carlton Ridenhour) once DJd.

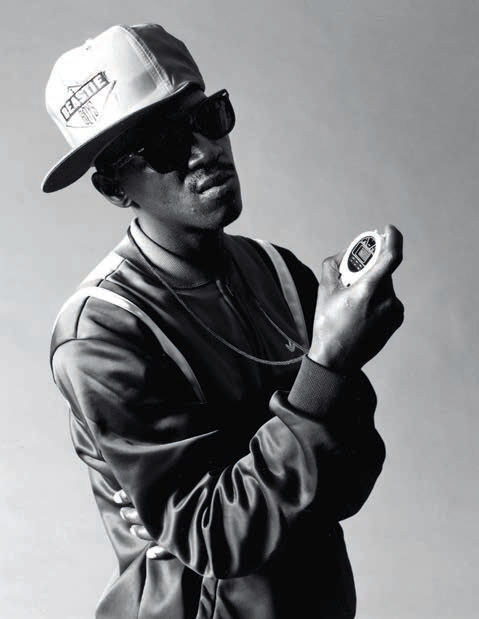

His first choice as musical partner was a multi-instrumentalist, former church choir singer and previously jailed burglar named William Drayton Jr who, when he was swapping verses with Chuck while they delivered furniture as a part-time job, called himself Flavor Flav. He would prove to be Chuck’s aural counterpoint, and a subversive presence, while an entire production team that Chuck had already collaborated with, the Bomb Squad – Hank Shocklee, his brother Keith and Eric ‘Vietnam’ Sadler – were also scooped up, along with turntablist Terminator X (Norman Rogers) and Professor Griff – Public Enemy’s self-styled Minister of Information (who would leave the group in 1989 after making anti-Semitic remarks).

At university Chuck D studied graphic design, and he put together his group with thoroughness and anticipation. Public Enemy always appeared to be one step ahead of expectations. Everyone had their roles, and whether they were serious (Chuck D), surreal (Flavor Flav) or publicly silent (Hank Shocklee), they carried them out with diligence. Their debut album, April 1987’s Yo! Bum Rush the Show, introduced the group’s politicised lyrics and intense studio aesthetic, winning critical acclaim and commercial success as Public Enemy went on tour with label-mates the Beastie Boys, but with It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back they only accelerated the process.

‘We knew we had to be different and we had to jolt people with the sound as well as the lyrics. It was about urgency. It had to sound like a wake-up call,’ Chuck D would later explain. ‘When we were making It Takes a Nation of Millions, we knew we had to take it further still, and make a What’s Going On for the hip hop generation. The concept, the musical segues, the beats per minute – no-one had done that sort of thing before. It reflected the past in terms of our influences, but it sounded like nothing else you’d ever heard.’

The album was made in little more than six weeks, working at New York’s Greene Street Recording under the working title Countdown to Armageddon. The Bomb Squad didn’t take part in the group’s extensive touring schedule, so when the performers came off tour they were greeted with a welter of semi-completed instrumental beds and possible samples. Chuck D would hole up to write lyrics, with contributions and catcalls from Flavor Flav, and the finished track would be signed off on by Hank Shocklee, who had the final right of say.

The philosophy of Shocklee and his cohorts was brutally simple: ‘We took whatever was annoying, threw it into a pot, and that’s how we came out with this group,’ he once noted. ‘We believed that music is nothing but organised noise. You can take anything – street sounds, us talking, whatever you want – and make it music by organising it. That’s still our philosophy, to show people that this thing you call music is a lot broader than you think it is.’

Chuck D would call Hank Shocklee the Phil Spector of hip-hop, although there was nothing lush about the Bomb Squad’s wall of sound. On ‘Bring the Noise’ a clarion call that announces itself after the introductory ‘Countdown to Armageddon’, there’s a collage that pivots on a drum sound from James Brown’s ‘Funky Drummer’, together with further samples of Brown, Funkadelic and the Commodores, which are pared down and manipulated into squealing, abrasively alive samples, Morse code scratching and tensile exhortations.

Public Enemy could match the rhythmic intensity of metal and the harsh, spectral blasts of free jazz. Hip-hop had never heard anything like this before. At a time when the prevailing standard was a drum loop and strident groove, Public Enemy studded every arrangement with information, creating a code that could be understood but not easily deciphered. There were only snatches of melody, but the beats had the pulse of excitement. On ‘Caught, Can We Get a Witness?’ the group answered up to the growing controversy in hip-hop over sampling – ‘This is a sampling sport,’ raps Chuck D, ‘But I’m giving it a new name’ – and the song, which storms forth, is at once a riposte to those threatening to issue writs and an example of the Bomb Squad’s blistering style; this was funk pushed to its extreme.

At the end of the same track Chuck D declares, ‘You singers are spineless/As you sing your senseless songs to the mindless/Your general subject love is minimal/It’s sex for profit,’ and his disdain for peddlers of self-satisfied R&B and uncommitted soul music was reflected in the radical orientation of Public Enemy’s lyrics. If the underlying sound of Public Enemy was revolutionary, they were making a noise that was literally trying to effect change, and Chuck D’s deep but sinuous baritone was the overt edge.

Public Enemy brought back to prominence a lineage of black music that included the self-determination and pride of James Brown, the politically charged Last Poets, and Gil Scott-Heron’s divining of society’s true standards. ‘We wanted our music to be the aural equivalent of black people wanting to scream out after having been silenced for so long,’ Chuck D would later say, and the words on It Takes a Nation of Millions are a crosssection of consciousness raising, mordant commentary and outright defiance.

Flavor Flav

On ‘Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos’, a steely, mid-tempo broadside, spiked with a glinting piano part, Chuck D recounts how he got a letter from the government about serving in the army, evoking the travails of Muhammad Ali, and contrasting the demands of the state with the indifference white America has shown to its black populace. ‘Here is a land that never gave a damn,’ he raps, as the story grows ever more involved, turning into a contemplation of power that is interrupted by a prison riot that becomes a jailbreak – after such a lengthy narrative, Chuck D wasn’t opposed to a little satisfaction for the listener.

Public Enemy saw the system as being corrosive in its mass indifference, vehement in its focused disdain. They would list those persecuted by J Edgar Hoover and the FBI and then wonder whether anything had changed, and in the same way that they remade sounds into a narrative they stripped back old ones so that the past revealed itself to the present. In such charged surrounds their rhetoric sounds like the opening of a manifesto, and it’s nigh on impossible not to enjoy the pleasure Public Enemy take in the likes of ‘Louder Than a Bomb’ or the bubbling, incantatory ‘Prophets of Rage’.

‘No one has been able to approach the political power that Public Enemy brought to hip hop,’ the late Adam Yauch, aka MCA of the Beastie Boys, would explain. ‘I put them on a level with Bob Marley … but where Marley’s music sweetly lures you in, then sneaks in the message, Chuck D grabs you by the collar and makes you listen.’

Public Enemy Brother James, Professor Griff, Flavor Flav, Terminator X, Chuck D, Brother Roger

Public Enemy were just as likely to dissect the easy acceptance of the status quo by the majority of the African-American community, with ‘She Watch Channel Zero?!’ ripping into a woman who values the fantasy satisfaction of her television soaps above the needs of family and friends. ‘Her brain’s retrained, by a 24-inch remote,’ raps Chuck D, while ‘Night of the Living Baseheads’ swings on a sirenlike horn sample to condemn the drug dealers who prey on their own communities and create the bleakly ubiquitous environment of black-on-black crime.

Flavor Flav proved his worth by not only accentuating the themes, but playing the livewire eccentric whose interjections often provided an off the wall alternative. His lead spot, ‘Cold Lampin’ with Flavor’ was madcap, taking the idea of flavour to a whole new level. As with the scratch-laden ‘Terminator X to the Edge of Panic’, ‘Cold Lampin’ was a reminder that Public Enemy worked as a unit (or a sports team) where they were only as good as their weakest link. In 1988 it was clear that they didn’t have one.

In a way Public Enemy were so impressive, so exemplary, that they weren’t highly influential. They were so site specific, so daunting, that few groups followed them (the Bomb Squad would have more of an effect, albeit in electronic music). The loping funk of gangsta rap would dominate hip-hop in the 1990s, but by then Public Enemy had stopped being simply a hip-hop group. In the same way that they were a band of unimpeachable technique, their message was relevant across the entire spectrum. It doesn’t matter who you are, or where you’re coming from: there’s inspiration and belief to be gained from It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back.