CBS

Produced by Guy Stevens

Released: December 1979

TRACKLISTING

01 London Calling

02 Brand New Cadillac

03 Jimmy Jazz

04 Hateful

05 Rudie Can’t Fail

06 Spanish Bombs

07 The Right Profile

08 Lost in the Supermarket

09 Clampdown

10 The Guns of Brixton

11 Wrong ’Em Boyo

12 Death or Glory

13 Koka Kola

14 The Card Cheat

15 Lover’s Rock

16 Four Horsemen

17 I’m Not Down

18 Revolution Rock

19 Train in Vain

Adversity was always a tonic for the Clash, a band that played as if they had their backs to the walls but were nonetheless intent on shooting out the lights. Triumph often ensued when the quartet were up against it, and that was never more apparent than on their landmark 1979 double album. London Calling is at once a shout out to fellow travellers and a disavowal of those who don’t stay the path; a staggering new vision of rock & roll in the autumn of punk, and a revivifying salute to the roots of popular music. It looked far and encompassed everything its gaze took in, channelling diverse styles and stances into a fierce, joyously rich sound. The end of the world may loom from the opening clamour of the title track, but the Clash were going to throw one hell of a going away party.

It was the third album from the group – vocalists/guitarists Joe Strummer and Mick Jones, bassist Paul Simonon and drummer Topper Headon – and it bore little relation to either predecessor. Their self-titled debut, issued in April 1977 as the punk explosion went from word of mouth to vinyl, was ragged and incendiary. The US arm of their record label refused to release it because they considered it unlistenable (it became a top selling import release in America and the execs reconsidered their decision in 1979). For their second long player, November 1978’s Give ’Em Enough Rope, they decamped to San Francisco and producer Sandy Pearlman, who gave them a heavy metal sheen and second thoughts.

The sound of Give ’Em Enough Rope simply added to the doubts that constantly assailed the Clash. The idea that they’d somehow sold out, which had become an obsession with some of punk’s fundamentalist believers – ‘the punk police’, Strummer sardonically labelled them – in the wake of their deal with London’s CBS Records, simply grew ever louder, especially after the Sex Pistols imploded during their first US tour and their fellow Londoners were left as the public face of punk rock. Interviews became confrontations and obituaries were prematurely penned.

In February 1979 the Clash visited America on what they tactfully called the Pearl Harbour ’79 tour. It was a comparatively compact run of dates, but eventful. They clashed with their US label, Epic, who baulked at financially supporting the tour and the presence of blues great Bo Diddley as opening act, and they eventually turned their back on the label’s promotional staff at the kind of meet-and-greet event that successful bands were supposed to politely smile their way through. They were hardly a priority after that.

But the shows were well received and it enhanced the gang-like mentality that the band had fostered in their early days, and after they parted ways with manager Bernie Rhodes – a one-time associate of Sex Pistols svengali Malcolm McLaren – the decks were cleared and they were ready to progress beyond simple expectations. Some American audiences were confused by the growing breadth of styles the band exhibited – wasn’t this all about gobbing and pogoing? – but it was just the beginning.

Back in London they found a new rehearsal space at the dingy Vanilla Studios in Pimlico, where they moved in their gear and a portable four-track recording rig and got to work writing in comparative anonymity. The building was a former rubber factory mainly used by car repair workshops, and throughout May and June of 1979 the band worked on songs together nearly every day. Strummer and Jones originated most of the initial ideas, but the brooding Simonon was also ready to start writing, and when they wanted a break they would play football with whoever was around on a nearby school playground. At one point they played a visiting cadre of CBS staffers and ripped into them.

‘It was the first time we played together in terms of creating the songs. There was a lot of experimentation,’ Paul Simonon recalled in the liner notes for the album’s 25th anniversary edition. ‘I’d hear tunes on the radio or a record, I’d play it, then Topper would join in. Or Mick and Joe would arrive with something, and we would work on it. It was like doubles at pingpong but with music as the ball.’

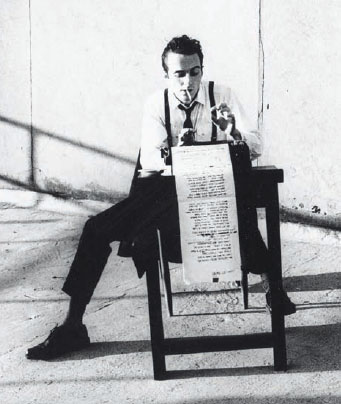

Joe Strummer

In August they went into Wessex Studios, linking up with veteran producer Guy Stevens, who was a voluble, enthusiastic catalyst, as likely to stalk the studio floor exhorting the musicians during a take as he was to throw a chair or wrestle with the recording engineer. Stevens was a former mod DJ, an inspiration to the Who, the first house producer at Island Records and, at one point, a guest of Her Majesty’s Prisons for eight months due to drug offences. On ‘Midnight to Stevens’ (a tribute the band cut after his death in 1981 at the age of 38, after overdosing on the prescription drugs he was taking for alcohol dependency), Strummer would sing, ‘Guy, you’ve finished the booze/And we’ve run out of speed/But the wild side of life/Is the one that we need.’ The eccentric, quite possibly deranged, producer fit right in and, once he’d sorted out his mini-cab bill, or called up Mott the Hoople’s Ian Hunter for a reassuring chat, or tuned the piano by pouring beer into it, the Clash were in good hands. Stevens valued the emotional integrity of a take over the technical qualities. Simonon, who was working hard to improve his playing after being a novice just three years prior, found him liberating.

Debates remain about what Stevens exactly did, but it’s clear that the album reflects his all-or-nothing outlook. On London Calling the Clash are flying, turning eclecticism into a kind of audacious rallying cry: if we can be whatever band we want, you can achieve the same as a person. The first side remains phenomenal and immersive, leaping from the lean guitar swagger of the title track to the vintage, prowling rockabilly of ‘Brand New Cadillac’ and the sax-driven jive of ‘Jimmy Jazz’, before ‘Hateful’ shows their appreciation to recent tour-mate Bo Diddley and ‘Rudie Can’t Fail’ is revealed as a ska exhortation.

At a time when punk was turning towards post-punk, electronic music was asserting itself and disco was informing black music – in other words, when fragmentation was becoming the norm – the Clash took everything in. The sonic diversity on London Calling isn’t just enjoyable, it’s emboldening. ‘There was a point where punk was getting narrower and narrower in terms of what it could achieve and where it would go,’ Jones would later recall. ‘They were painting themselves into a corner. We thought that you could do any kind of music.’

The idea that the Clash are ready to turn everything upside down is apparent from the first chords of ‘London Calling’. It may be a classic setting of the scene, establishing both the landscape and the personal parameters – ‘don’t look to us,’ spits Strummer, ‘phoney Beatlemania has bitten the dust’ – but the further the song goes the more unsettled reality is shown to be. ‘The ice age is coming, the sun’s zooming in,’ adds Strummer, and confusion reigns. There are too many ways for the world to end, and if they’re competing with the likes of ‘nuclear errors’ then it’s not clear what will prevail, even as Strummer offers a closing hint of apocalyptic charm with a request for a smile.

The Clash on the ‘London Calling’ video shoot (left to right): Topper Headon, Joe Strummer, Paul Simonon, Mick Jones

The only thing that bears true is the arrangement, especially the stirring bassline, and throughout the album the band plays with a passion that the world they’re observing rarely has. The band retains an anti-authoritarian fervour, but Strummer’s take on what he’s witnessing is more complex; a riot won’t solve anything. In the bracing ‘Spanish Bombs’ the lyric references the defeated Republican forces from the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s, a struggle that was a rallying cry for the Left. But there are references to the Basque separatists of ETA, whose bombings were part of 1979’s roll call of international terrorism. ‘Can I hear the echo from the days of ’39?,’ asks Strummer, and suddenly there’s nothing straightforward about the song’s intentions.

It’s followed by ‘The Right Profile’, a soulful rave-up about the 1950s Hollywood actor Montgomery Clift and, across the double album, larger than life characters, fictional or based on real life, give Strummer and his bandmates more room to move. The old R&B legend of Stagger Lee, based on a murder that informed an early folk standard, is updated for a Jamaican age with a cover of the Rulers’ ‘Wrong ’Em Boyo’. The band’s taste for reggae didn’t just result in specific tunes, it indirectly influenced Strummer’s belief in writing about the world – he wanted to be like the MCs who toasted on Trench Town 12-inches that were a form of current affairs.

Simonon was the band’s reggae obsessive, and it flowed through to ‘Guns of Brixton’, a track he wrote and sang sneering lead on that also demonstrates the versatility of drummer Topper Headon, whose extracurricular dependencies didn’t prevent him playing a crucial role. The band’s ideas and Stevens’ production even stretched to a take on Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound with ‘The Card Cheat’, where another of the album’s antihero characters is backed up by a layered sound that was achieved by recording the song twice and combining the takes.

As befitting a classic album, there are songs here that no-one thought the Clash capable of achieving, and that they would never be able to duplicate on later releases. On the brisk, reflective ‘Lost in the Supermarket’, Strummer wrote an autobiographical lyric for Jones, who then sang its descriptions of growing up and the subsequent encroachment of consumerism. The double album even closed with something of a pop hit, courtesy of Mick Jones’ catchy last minute inclusion ‘Train in Vain’, a guitar and keyboards groove that was suffused with a healthy optimism.

The Clash could still stand tall like outlaws determined not to be taken in, providing a righteous profile on the likes of ‘Four Horsemen’ and ‘Death or Glory’. But the best indicator is the defiant ‘I’m Not Down’, which sketches a maturity borne of going against the odds. ‘I’ve been beat up, I’ve been thrown out/But I’m not down, no I’m not down,’ Mick Jones sang. ‘I’ve been shown up, but I’ve grown up/And I’m not down, no I’m not down.’

That was the Clash at the end of the 1970s, old enough and tough enough to know what was at stake and to celebrate the possibilities. The world never ends on London Calling because there’s always another song, another passion, another sound, or another belief to take up the slack. It’s a consummate rock &roll experience, as vivid and thrilling now as the day it appeared.