Factory

Produced by Martin Hannett

Released: July 1980

TRACKLISTING

01 Atrocity Exhibition

02 Isolation

03 Passover

04 Colony

05 A Means to an End

06 Heart and Soul

07 Twenty Four Hours

08 The Eternal

09 Decades

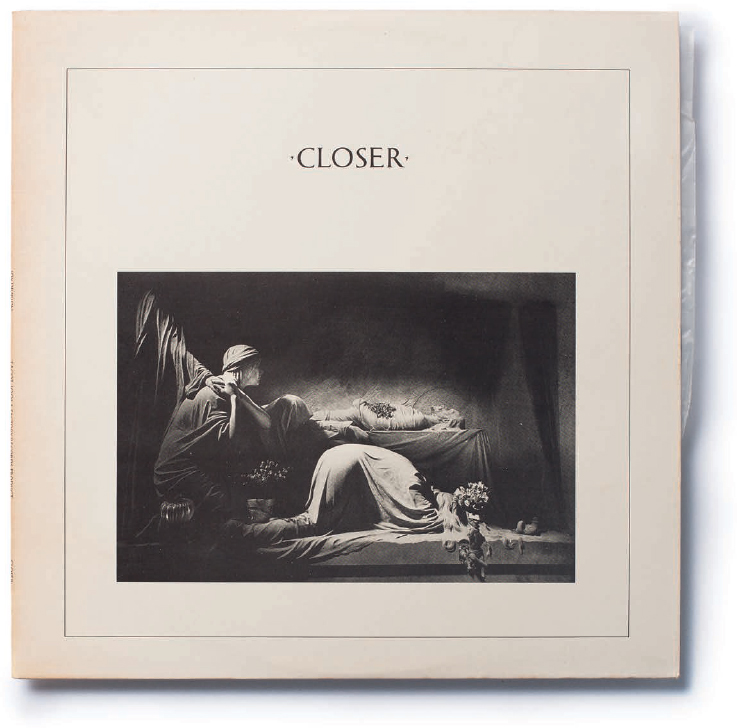

It’s difficult, nigh on impossible, to separate Joy Division’s second and final album, Closer, from the circumstances surrounding its release. On 18 May 1980, with the album finished and awaiting release, the Manchester group’s frontman, Ian Curtis, hung himself in the kitchen of his family home. His estranged wife, Deborah, discovered his body. His death is the lens through which the singer and lyricist’s life’s work is now viewed; the music and the man’s passing inextricably linked. But while these nine tracks hold portents of Curtis’ future, they also exist as an immaculate listening experience. It’s one that is movingly beautiful in its contemplation of the human experience.

The ’70s end and the ’80s begin with Closer. It is an album that ushers out punk’s rage and introduces post-punk’s space, offering a synthesis of the guitar and the keyboard, the emotive and the distant. It is close to scary to consider how quickly Curtis, guitarist Bernard Sumner, bassist Peter Hook and drummer Stephen Morris had moved. In 1977 they’d been playing catch-up; an awkward punk band playing abrasive, limited tunes around England’s north-west. They became Joy Division in early 1978, and released their debut album, Unknown Pleasures, in June 1979 as they became increasingly cohesive and transformative. They improved season to season, growing more popular in Britain and Europe.

One of their few outside influences was eccentric producer Martin Hannett, who’d help catch the cold post-industrial threat of Manchester on Unknown Pleasures. For Closer he helped turn the band inwards, matching Curtis’ lyrics to a sound that’s heartbreakingly still. With their precise, separated drum sounds, minimalist keyboards and the pulse-like bass of Hook, the songs are witnesses to the interior landscape Curtis sings about. Closer is an album without physicality and detail – what’s tangible is the emotional topography.

‘This is the crisis I knew had to come/Destroying the balance I’d kept,’ begins Curtis on ‘Passover’, ‘Doubting, unsettling and turning around/Wondering what will come next’, and steadily his bandmates make clear what will come next as the icy splash of percussion and brief guitar squalls grow stronger as Hook’s bass briefly imposes before the song drifts away. The singer – who was suffering epileptic attacks on stage and trying to manage the resulting prescription drug-induced depression – was evolving as a vocalist, with his distressed vigour on the likes of ‘Colony’ counter-pointed by the stark baritone croon he used for ‘Eternal’.

Joy Division would evolve into New Order after Curtis’ death, and there are hints of that group’s sensibility on ‘Isolation’ – an icy, glinting piece of alternative disco whose framework would prove enormously influential to the first wave of electronic acts in the ’80s. Barely a note feels wasteful on Closer, and it has a distinct power that grows more apparent as the nine tracks unfold. The high bass and determined rhythm of ‘A Means to an End’ gives way to the nervy rhythms and elegant melody of ‘Heart and Soul’ before the swirling ‘Twenty Four Hours’ takes hold.

Numerous lines speak to the personal struggles Curtis was enduring, but it would be wrong to write off Closer as a morbid, self-obsessed piece of work. By the closing ‘Decades’, where the setting reaches ‘hell’s dark chambers’, the music has attained a touching transcendence. Ian Curtis never wallowed in suffering. More often he was brave to describe what he was going through, and it made for a singular and enduring album that was the musician’s best hope. ‘But if you could just see the beauty/These things I could never describe,’ he sang on ‘Isolation’. ‘These pleasures a wayward distraction/This is my one lucky prize.’