Introduction

At Merlin’s You Meet with Delight

In the early years of the Islamic Golden Age, around 760 CE, the new leader of the Abbasid Dynasty, Abu Ja’far al-Mansur, began scouting land on the eastern edge of Mesopotamia, looking to build a new capital city from scratch. He settled on a promising stretch of land that lay along a bend in the Tigris River, not far from the location of ancient Babylon. Inspired by his readings of Euclid, al-Mansur decreed that his engineers and planners should build a grand metropolis at the site, constructed as a nested series of concentric circles, each ringed with brick walls. The city was officially named Madinat al-Salam, Arabic for “city of peace,” but in common parlance it retained the name of the smaller Persian settlement that predated al-Mansur’s epic vision: Baghdad. Within a hundred years, Baghdad contained close to a million inhabitants, and it was, by many accounts, the most civilized urban environment on the planet. “Every household was plentifully supplied with water at all seasons by the numerous aqueducts which intersected the town,” one contemporary observer wrote, “and the streets, gardens and parks were regularly swept and watered, and no refuse was allowed to remain within the walls. An immense square in front of the imperial palace was used for reviews, military inspections, tournaments and races; at night the square and the streets were lighted by lamps.”

An illustration of a life-sized elephant clock, from al-Jazari’s The Book of Knowledge and Ingenious Mechanisms

More significant, though, than the elegance of Baghdad’s broad avenues and lavish gardens was the scholarship sustained inside the Round City’s walls. Al-Mansur founded a palace library to support scholars and funded the translation into Arabic of science, mathematics, and engineering texts originally written in the days of classical Greece—works by Plato, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Hippocrates, and Euclid—along with Hindu texts from India that contained important advances in trigonometry and astronomy. (These translations eventually turned out to be a kind of lifeboat for these ancient ideas, keeping them in circulation through the European Dark Ages.) A few decades later, under the leadership of al-Mansur’s son, al-Manum, a new institution took root inside Baghdad’s walls, a mix of library, scientific academy, and translation bureau. It became known as Bayt al-Hikma: the House of Wisdom. For three hundred years, it was the seat of Islamic scholarship, until the Mongols sacked Baghdad in the siege of 1258, destroying the books from the House of Wisdom by submerging them in the Tigris.

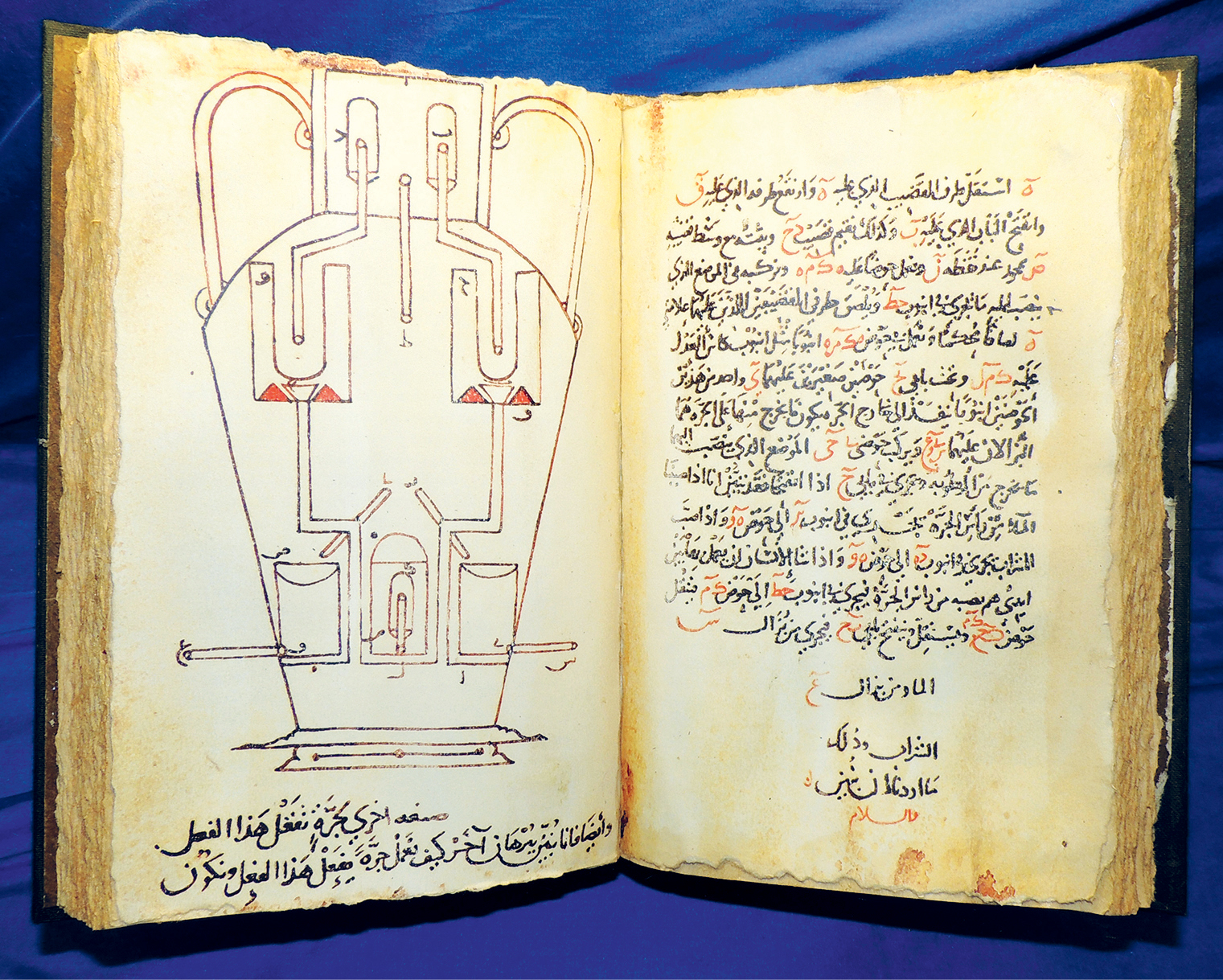

In the first years of the House of Wisdom, al-Manum commissioned three talented brothers, now known as the Banu Musa, to write a book describing classical engineering designs inherited from the Greeks. As the project evolved, the Banu Musa expanded their brief to include their own designs, showcasing the advances in mechanics and hydraulics that surrounded them in Baghdad’s flourishing intellectual culture. The work they eventually published, The Book of Ingenious Devices, now reads like a prophesy of future engineering tools: crankshafts, twin-cylinder pumps with suction, conical valves employed as “in-line” components—mechanical parts centuries ahead of their time, all represented in detailed schematics. Two centuries later, the Banu Musa’s work inspired an even more astonishing project, written and illustrated by the Islamic engineer al-Jazari, The Book of the Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanisms. It contained stunning illustrations, adorned with gold leaf, of hundreds of machines, with careful notes explaining their operational principles. Float valves that prefigure the design of modern toilets, flow regulators that would eventually be used in hydroelectric dams and internal combustion engines, water clocks more accurate than anything Europe would see for four hundred years. The two books contain some of the earliest sketches of technology that would become essential components in the industrial age, enabling everything from assembly-line robots to thermostats to steam engines to the control of jet airplanes.

Pages from the Banu Musa’s The Book of Ingenious Devices

These two books of “ingenious” machines deserve a prominent place in the canon of engineering history, in part as a corrective to the too-frequent assumption that Europeans single-handedly invented most modern technology. But there is something else about these two books that doesn’t quite fit the standard account of groundbreaking scientific work, something that is immediately visible to the nonengineer flipping through their pages. The overwhelming majority of the mechanisms illustrated in the two volumes are objects of amusement and mimicry: fountains that spout water in rhythmic bursts; mechanical flute players; automated drumming machines; a peacock that dispenses water when you pull its feathers and then proffers a miniature servant with soap; a boat filled with robotic musicians that can serenade an audience while floating in a lake; a clock built into the shape of an elephant that chimes on the half hour.

There is a puzzle lurking in the genius of the Banu Musa and al-Jazari. How can it be that such advanced engineering expertise should be devoted to toys? The revolutionary ideas diagrammed in the pages of these ancient books would eventually transform the industrial world. But those ideas first came into being as playthings, as illusions, as magic.

—

Fast-forward a thousand years. The mechanical amusements first diagrammed by al-Jazari and the Banu Musa have become profitable entertainment across Europe, nowhere more so than in the streets of London, which teem with spectacles and curiosities. By the early 1800s, a bustling new industry of illusion has taken root in the West End. Robert Barker’s immersive Panorama dazzles audiences with a simulated 360-degree rooftop view of the city; at the Lyceum Theatre, Paul de Philipsthal terrifies spectators with his multimedia spook show, the Phantasmagoria. An exhibit of wax statues, curated by a certain Madame Tussaud, premieres at the Lyceum, but isn’t a hit. (Tussaud wouldn’t create her famous museum for another thirty years.) In Hanover Square, just south of Oxford Street, a Swiss inventor and showman with the delightful name John-Joseph Merlin runs an eclectic establishment known as Merlin’s Mechanical Museum. In modern terms, Merlin’s shop is a kind of hybrid between a science museum, a gaming arcade, and a maker lab. You can marvel at moving mechanical dolls, try your luck at gambling machines, and enjoy the sweet melodies of music boxes. But Merlin is not simply an impresario; he is also a mentor of sorts, encouraging the “young amateurs of mechanism” to try their own hands at invention.

Born in Belgium in 1735, Merlin is a clockmaker by trade, and like many horologists of that period, he has long been intrigued by the idea that the mechanized movement of the pendulum clock and its descendants could be scaled up into more impressive feats—of productive labor, to be sure, but also something else: flights of fancy, wonder, illusion. You could build machines that could tell time, weave fabric, maybe even perform elementary calculations. But you could also build machines that mimicked physical behavior for less utilitarian purposes: for the sheer delight that human beings have always found in the imitation of life. The construction of these early robots, called automata in their time, had been one of the great extravagances of courtly life during the period, designed to amuse and curry favor with the aristocracy. These inventions evolved out of mechanical clocks, popular in the 1600s, featuring elaborate mise-en-scènes of villages or musicians that mark the passing of the hour by bursting into life. By the end of the seventeenth century, the clocks blossomed into miniature stage shows, called clockworks, that presented simple narratives using the mechanized movements of hundreds of distinct elements. Many of them featured biblical themes. In 1661, a London tavern showcased a clockwork rendition of Eden. According to a pamphlet published at the time, it presented “Paradise Translated and Restored, in a Most Artfull and Lively Representation of the Severall Creatures, Plants, Flowers, and Other Vegetables, in Their Full Growth, Shape, and Colour . . . A Representation of that Beautiful Prospect Adam had in Paradise.” (When the robots eventually write the history of their species, these animated tableaux will serve nicely as a creation myth.)

By the early 1700s, the focus shifted from re-creating the bustle of an animated village or garden to building increasingly lifelike simulations of individual organisms. In the first half of the eighteenth century, the French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson famously constructed an automaton called the Digesting Duck that consumed grain, flapped its wings, and—the pièce de résistance—actually defecated after eating. A few decades later, in 1758, a Swiss horologist named Pierre Jaquet-Droz traveled to Madrid to present an array of wonders to King Ferdinand, most of them pendulum or water clocks that featured animated storks, flute-playing shepherds, and songbirds—the mechanical descendants of al-Jazari’s ingenious devices. The audience with Ferdinand secured Jaquet-Droz financially and he embarked on an ambitious streak of automaton creation, arguably the most artistic and innovative mechanical engineering that the world had ever seen. His crowning achievement, completed in 1772, was the Writer, a mechanical boy composed of more than six thousand distinct parts, seated on a stool with a quill pen in hand. The boy could be programmed to write any combination of words using up to forty characters. Once instructed—via a series of cams hidden inside the contraption—he dipped his pen in an inkwell, shook it twice, and began writing the words with a studious precision, his eyes following the pen as he wrote. The Writer was not a computer in the modern sense of the word, but it is rightly considered a milestone in the history of programmable machines.

The Writer, an automaton created by Pierre Jaquet-Droz in 1772

Jaquet-Droz’s son, Henri-Louis, began displaying the Writer in London in 1776, part of a new exhibition in Covent Garden called the “Spectacle Mécanique.” Inspired by these fantastical creatures, Merlin began making and collecting automatons himself. To showcase some of this work, he opened Merlin’s Mechanical Museum in 1783, running a promotional notice assuring that “Ladies and Gentlemen who honour Mr Merlin with their Company may be accommodated with TEA and COFFEE at one Shilling each.” As Simon Schaffer puts it, Merlin “prowled the borderlines of showmanship and engineering,” not unlike the Hollywood special-effects studios that descend, almost directly, from Merlin and his contemporaries.

Merlin’s ingenuity took him in many directions: he invented a self-propelling wheelchair, a mechanical Dutch oven, a pump that automatically freshens air in hospital rooms, a deck of playing cards with braille-like encodings that enables blind people to play whist. He dabbled in the design of musical instruments. Today, he is probably best known for inventing roller skates. Some of these contraptions he displayed in the Mechanical Museum, but he kept two prize creations in his workshop in the attic above the museum: two miniature female automata, no more than a foot or two tall. One creature walked across a four-foot space, holding an eyeglass and bowing respectfully toward the onlookers. The other was a dancer holding an animated bird.

Conventional historical accounts are typically oriented around Great Events: battles fought, treaties signed, speeches delivered, elections won, leaders assassinated. Or the textbooks follow the long arc of incremental change: the rise of democracy or industrialization or civil rights. But sometimes history is shaped by chance encounters, far from the corridors of power, moments when an idea takes root in someone’s head and lingers there for years until it makes its way onto the main stage of global change. One of those encounters happens in 1801, when a mother brings her precocious eight-year-old son to visit Merlin’s museum. His name is Charles Babbage. The old showman senses something promising in the boy and offers to take him up to the attic to spark his curiosity even further. The boy is charmed by the walking lady. “The motions of her limbs were singularly graceful,” he would recall many years later. But it is the dancer that seduces him. “This lady attitudinized in a most fascinating manner,” he writes. “Her eyes were full of imagination, and irresistible.”

The encounter in Merlin’s attic stokes an obsession in Babbage, a fascination with mechanical devices that convincingly emulate the subtleties of human behavior. He earns degrees in mathematics and astronomy as a young scholar, but maintains his interest in machines by studying the new factory systems that are sprouting across England’s industrial north. Almost thirty years after his visit to Merlin’s, he publishes a seminal analysis of industrial technology, On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, a work that would go on to play a pivotal role in Marx’s Das Kapital two decades later. Around the same time, Babbage begins sketching plans for a calculating machine he calls the Difference Engine, an invention that will eventually lead him to the Analytical Engine several years later, now considered to be the first programmable computer ever imagined.

We don’t know if the eight-year-old Babbage made a notable impression on Merlin himself. The showman died two years after Babbage’s visit, and his collection of wonders—including the captivating automata—were sold to a rival named Thomas Weeks, who ran his own museum a few blocks away on Great Windmill Street. Weeks never put the dancer or the walking lady on display; they remained in his attic, gathering cobwebs until Weeks himself died in 1834, and the entire lot was put up for auction. Somehow, after all those years, Babbage found his way to the auction and purchased the dancer for thirty-five pounds. He refurbished the machine and put it on display in his Marylebone town house, a few feet away from the Difference Engine. In a sense, the two machines belonged to different centuries: the dancer was the epitome of Enlightenment-era fantasy; the Difference Engine an augur of late twentieth-century computation. The dancer was a thing of beauty, an amusement, a folly. The engine was, as its name suggested, a more serious affair: a tool for the age of industrial capitalism and beyond. But according to Babbage’s own account, the passion for mechanical thinking that led to the Difference Engine began with that moment of seduction in Merlin’s attic, in the “irresistible eyes” of a machine passing for a human for no good reason other than the sheer delight of the illusion itself.

—

Delight is a word that is rarely invoked as a driver of historical change. History is usually imagined as a battle for survival, for power, for freedom, for wealth. At best, the world of play and amusement belongs to the sidebars of the main narrative: the spoils of progress, the surplus that civilizations enjoy once the campaigns for freedom and affluence have been won. But imagine you are an observer of social and technological trends in the second half of the eighteenth century, and you are trying to predict the truly seismic developments that would define the next three centuries. The programmable pen of Jaquet-Droz’s writer—or Merlin’s dancer and her “irresistible eyes”—would be as telling a clue about that future as anything happening in Parliament or on the battlefield, foreshadowing the rise of mechanized labor, the digital revolution, robotics, and artificial intelligence.

This book is an extended argument for that kind of clue: a folly, dismissed by many as a mindless amusement, that turns out to be a kind of artifact from the future. This is a history of play, a history of the pastimes that human beings have concocted to amuse themselves as an escape from the daily grind of subsistence. This is a history of what we do for fun. One measure of human progress is how much recreational time many of us now have, and the immensely varied ways we have of enjoying it. A time-traveler from five centuries ago would be staggered to see just how much real estate in the modern world is devoted to the wonderlands of parks, coffeeshops, sports arenas, shopping malls, IMAX theaters: environments specifically designed to entertain and delight us. Experiences that were once almost exclusively relegated to society’s elites have become commonplace to all but the very poorest members of society. An average middle-class family in Brazil or Indonesia takes it for granted that their free time can be spent listening to music, marveling at elaborate special effects in Hollywood movies, shopping for new fashions in vast palaces of consumption, and savoring the flavors of cuisines from all over the world. Yet we rarely pause to consider how these many luxuries came to be a feature of everyday life.

History is mostly told as a long fight for the necessities, not the luxuries: the fight for freedom, equality, safety, self-governance. Yet the history of delight matters, too, because so many of these seemingly trivial discoveries ended up triggering changes in the realm of Serious History. I have called this phenomenon “the hummingbird effect”: the process by which an innovation in one field sets in motion transformations in seemingly unrelated fields. The taste for coffee helped create the modern institutions of journalism; a handful of elegantly decorated fabric shops helped trigger the industrial revolution. When human beings create and share experiences designed to delight or amaze, they often end up transforming society in more dramatic ways than people focused on more utilitarian concerns. We owe a great deal of the modern world to people doggedly trying to solve a high-minded problem: how to construct an internal combustion engine or manufacture vaccines in large quantities. But a surprising amount of modernity has its roots in another kind of activity: people mucking around with magic, toys, games, and other seemingly idle pastimes. Everyone knows the old saying “Necessity is the mother of invention,” but if you do a paternity test on many of the modern world’s most important ideas or institutions, you will find, invariably, that leisure and play were involved in the conception as well.

Although this account contains its fair share of figures like Charles Babbage—well-to-do Europeans tinkering with new ideas in their parlors—it is not just a story about the affluent West. One of the most intriguing plot twists in the story of leisure and delight is how many of the devices or materials originated outside of Europe: those mesmerizing automata from the House of Wisdom, the intriguing fashions of calico and chintz imported from India, the gravity-defying rubber balls invented by Mesoamericans, the clove and nutmeg first tasted by remote Indonesian islanders. In many ways, the story of play is the story of the emergence of a truly cosmopolitan worldview, a world bound together by the shared experiences of kicking a ball around on a field or sipping a cup of coffee. The pursuit of pleasure turns out to be one of the very first experiences to stitch together a global fabric of shared culture, with many of the most prominent threads originating outside Western Europe.

I should say at the outset that this history deliberately excludes some of life’s most intense pleasures—including sex and romantic love. Sex has been a central force in human history; without sex, there is no human history. But the pleasure of sex is bound up in deep-seated biological drives. The desire for emotional and physical connections with other humans is written into our DNA, however complex and variable our expression of that drive may be. For the human species, sex is a staple, not a luxury. This history is an account of less utilitarian pleasures; habits and customs and environments that came into being for no apparent reason other than the fact that they seemed amusing or surprising. (In a sense, it is a history that follows Brian Eno’s definition of culture as “all the things we don’t have to do.”) Looking at history through this lens demands a different emphasis on the past: exploring the history of shopping as a recreational pursuit instead of the history of commerce writ large; following the global path of the spice trade instead of the broader history of agriculture and food production. There are a thousand books written about the history of innovations that came out of our survival instincts. This is a book about a different kind of innovation: the new ideas and technologies and social spaces that emerged once some of us escaped from the compulsory labor of subsistence.

The centrality of play and delight does not mean that these stories are free of tragedy and human suffering. Some of the most appalling epochs of slavery and colonization began with a new taste or fabric developing a market, and unleashed a chain of brutal exploitation to satisfy that market’s demands. The quest for delight transformed the world, but it did not always transform it for the better.

—

In 1772, Samuel Johnson paid a visit to one of the predecessors of Merlin’s Mechanical Museum, a showcase run by an engineer named James Cox, who became one of Merlin’s mentors. Exploring Cox’s exhibition was like walking through the pages of al-Jazari’s illustrated book: the rooms were filled with animated elephants, peacocks, and swans, glittering with jewels. Johnson published an account of his visit in the Rambler. “It may sometimes happen,” he wrote, “that the greatest efforts of ingenuity have been exerted in trifles; yet the same principles and expedients may be applied to more valuable purposes, and the movements, which put into action machines of no use but to raise the wonder of ignorance, may be employed to drain fens, or manufacture metals, to assist the architect, or preserve the sailor.”

In other words, the ingenious “trifles” of the automata often serve as a kind of augur of more substantial developments to come. This foreshadowing effect is clearly visible in the commentary that built up around the great automata of the eighteenth century: Jaquet-Droz’s Writer, Vaucanson’s duck, the famous chess-playing “Mechanical Turk” originally designed in the 1770s by the Hungarian inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen. (The Turk turned out to be less of a mechanical achievement, as the chess was actually played by a man hidden inside the contraption.) While these contraptions sparked amazement and debate in their prime—several essays were published in the late 1700s trying to solve the mystery of the Turk’s chess abilities—they reached their cultural peak in the middle of the nineteenth century, well after most of their showcases had gone out of business. The automata inspired Marx’s theories on the future of labor and propelled Babbage toward his prophetic vision of mechanized intelligence. They planted the seed for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Edgar Allan Poe’s attempt to explain the secrets of the Mechanical Turk laid the groundwork for his invention of the detective story. The automata were animated by the scientific and engineering knowledge of the eighteenth century, but they unleashed broader hopes and fears that belonged properly to the nineteenth. In both their mechanical design and their philosophical implications, the automata were ahead of their time.

This phenomenon turns out to appear consistently throughout the history of humanity’s trifles. The guilty pleasures of life often give us a hint of future changes in society, whether those pleasures take the form of English ladies shopping for calico fabrics in London in the late 1600s, or ancient Roman feasts laden with spices from the far corners of the globe, or carnival hucksters promoting strange optical devices that create the illusion of moving pictures, or computer programmers at MIT in the 1960s playing Spacewar! on their million-dollar mainframes. Because play is often about breaking rules and experimenting with new conventions, it turns out to be the seedbed for many innovations that ultimately develop into much sturdier and more significant forms. The institutions of society that so dominate traditional history—political bodies, corporations, religions—can tell you quite a bit about the current state of the social order. But if you are trying to figure out what’s coming next, you are often better off exploring the margins of play: the hobbies and curiosity pieces and subcultures of human beings devising new ways to have fun. “Each epoch dreams the one to follow, creates it in dreaming,” the French historian Michelet wrote in 1839. More often than not, those dreams do not unfold within the grown-up world of work or war or governance. Instead, they emerge from a different kind of space: a space of wonder and delight where the normal rules have been suspended, where people are free to explore the spontaneous, unpredictable, and immensely creative work of play. You will find the future wherever people are having the most fun.