1

Fashion and Shopping

The Calico Madams

The sea snail Hexaplex trunculus lives in shallow waters and tidal pools along the coast of the Mediterranean, and along the shores of the Atlantic, from Portugal down to the western Sahara. To the untrained eye, the murex snail, as it is also called, looks like an ordinary mollusk, housed in a conical shell ringed by bands of spikes. Millions of years ago, the snail evolved a kind of bioweapon used to sedate prey and defend itself against predators: an inky secretion that contains a rare compound called dibromoindigo. Almost four thousand years ago, the Minoan civilization based in the Aegean islands discovered that the murex snail secretion could be used as a dye to create one of the rarest of shades: the color purple.

Over time, the purple dye took on the name of a town in southern Phoenicia, Tyre, where it was mass-produced. The exact procedure for manufacturing Tyrian purple is unknown today, although Pliny the Elder included a fragmentary recipe in his Natural History. Modern attempts to re-create the dye suggest that more than ten thousand snails were required to produce just one gram of Tyrian dye. But if the production techniques remain a mystery, the historical record is clear about one thing: Tyrian purple endured as a symbol of status and affluence for at least a thousand years. Bands of Tyrian purple were woven into the tunics of Roman senators; a child conceived by one of the emperors of Byzantium was given the honorific Porphyrogenitus—literally, “born in the purple.” Over the millennium that passed from the age of the Phoenicians to the fall of Rome, an ounce of Tyrian purple dye was worth significantly more than an ounce of gold, a valuation that compelled sailors to explore the entire coastline of the Mediterranean for colonies of murex snails.

Eventually, though, the supply of Hexaplex trunculus in the Mediterranean could not keep up with the demand for Tyrian purple, and a few intrepid Phoenician sailors began to contemplate more ambitious voyages in search of the mollusk, beyond the placid waters of the inland sea, out onto the gray, turbulent waves of the Atlantic itself. The Phoenicians had already passed through the Strait of Gibraltar in search of alluvial tin deposits, their distinctive cedar-planked ships, powered by thirteen oarsmen on each side, hugging the coast of Spain through waters that, technically speaking, belonged to the Atlantic. But it was the murex snail that compelled them to take on the towering waves and uncharted waters of the open ocean. They ventured down the coast of North Africa, where they eventually discovered a bounty of sea snails that would keep the aristocracy cloaked in purple well into the Dark Ages. The legacy of these voyages extends far beyond simple fashion. The passage out of the Mediterranean into the vast mystery of the Atlantic marked a true threshold moment in the history of human exploration. “The Phoenicians’ now-proven aptitude for sailing the North African coast was to be the key that unlocked the Atlantic for all time,” Simon Winchester writes. “The fear of the great unknown waters beyond the Pillars of Hercules swiftly dissipated.” Think of all the ways the world would be transformed by vessels launched from Mediterranean countries, exploring the Atlantic and beyond. Those vessels would eventually leave in search of gold, or religious freedom, or military conquest. But the first siren song that lured them onto the open ocean was a simple color.

The murex snail

Garment design has driven technological innovation from the very beginning of human existence. Shears, sewing needles, and scrapers for converting animal skins into protective coverings for the body are among the oldest tools recovered from the Paleolithic age. To be sure, much of that innovation was utilitarian in nature. Ascots and hoop skirts aside, most clothing has some functional value, and certainly our ancestors fifty thousand years ago were making clothes with the explicit aim of keeping warm and dry and protected from potential threats. The fact that so much technological innovation—from the first knitting needles to hand looms to the spinning jenny—has emerged out of textile production can seem, at first glance, more a matter of necessity’s invention. And yet the archeological record is replete with early examples of purely decorative toolmaking: a shell necklace discovered in the Sikul Cave in Israel was crafted more than a hundred thousand years ago. As soon as humans became toolmakers, they were making jewelry.

Whatever mix of playfulness and practicality drove early human garment design, the invention of Tyrian purple announced a fundamental shift toward delight and surprise—a shift, in a sense, from function to fashion. No one needs the color purple. It does not protect you against malaria, or supply useful proteins, or reduce the chances that you will die in childbirth. It just looks nice, particularly if you live in a world where purple garments happen to be rare.

You might reasonably object at this point that those Phoenician snail wranglers—and the oarsmen that first took them past the Strait of Gibraltar—were motivated by financial gain, and not some sublime aesthetic response to purple itself. That is certainly the canonical way of telling it. As soon as we invented liquid currencies, human beings were suddenly willing to take on improbably ambitious and dangerous schemes if the price happened to be right. People left the safety of the Mediterranean because there was money in it—a motivation that was certainly powerful, but not particularly newsworthy.

A comparable argument might be made for the importance of status in the display of those purple garments. Humans evolved in hierarchical societies and most of us acknowledge that status-seeking is a common, if sometimes regrettable, driver of human behavior. The Phoenician aristocracy wanted to dye their clothes in shades of Tyrian purple so they could display their superiority over the commoners, and they were willing to pay for the privilege. Again, the causal chain is a familiar one: people will go to great lengths to satisfy the needs of the ruling elite if they are amply compensated for their labor. The fact that this labor involved harvesting thousands of snails may be an intriguing historical yarn, but does it really tell us anything new about the deep-seated forces that drive historical change?

With all due respect to Occam’s razor, I think in this case the simpler story is not correct, or at least it fails to include the most interesting part of the explanation. The financial gain or status symbols were secondary effects; the initial fixation with purple was the prime mover. Take away the purely aesthetic response to the Tyrian dye, and the whole chain of exploration, invention, and profit falls apart. This turns out to be a recurring pattern in the history of play. Because delightful things are valuable, they often attract commercial speculation, which funds and cultivates new technologies or markets or geographic exploration. When we look back at that process, we tend to talk about it in terms of the money and markets or the vanity of the ruling elite driving the new ideas. But the money has its own masters, and in many cases the dominant one is the human appetite for surprise and novelty and beauty. If you dig past the archeological layers of technological invention, profit motive, conquest, and status-seeking, you will often find an unlikely stratum that lies beneath the more familiar layers: the simple pleasure of a new experience—in this case, the red and blue cones of our retinas registering a strange hybrid shade almost never found in nature. Somehow the story gets cast in the retelling as a tale of heroic inventors or efficient capital markets or brutal exploitation. That initial moment of delight becomes an afterthought, a footnote to the master narrative.

Nowhere is this oversight more glaring than in the story behind the greatest technological upheaval of modern times: the industrial revolution.

—

In the last few decades of the seventeenth century, a new pattern became visible—arguably for the first time in history—on the streets of a few select neighborhoods in London: St. James, Ludgate Hill, Bank Junction. A row of shops, each offering tantalizing collections of fabric, or jewelry, or home furnishings, clustered together on a few city blocks. The shopfronts featured large glass window displays, with merchandise arranged in visually arresting styles. The interiors were festooned with pillars, elaborate mirrors and lighting, sculpted cornices, and draperies. An observer from the early 1700s described them as “perfectly gilded theaters.”

All of this theatrical elegance was designed to create a new kind of aura around the simple act of buying goods. Earlier in the seventeenth century, shopping galleries like the New Exchange and Westminster Hall had created bustling, immersive spaces for commercial transactions, but the new shops added a measure of grandeur and elegance that made the galleries seem cramped and oppressive by comparison. In the exchanges, each vendor’s space was small and largely unfurnished, closer to the stalls of a traveling fair or street peddlers. The new shops created a much more sumptuous environment, as though the consumer were entering the drawing room of a minor lord instead of bargaining with a street hawker. For the first time, the design of the shop became a part of the marketing message. Indeed, in an age that predates the modern craft of advertising, those shop designs were among the very first forms of marketing ever concocted. “The seductive design of shops was intended to encourage customers to stay and to look around, to see shopping as a leisurely pursuit and an exciting experience,” writes historian Claire Walsh. “The more time a customer spent in the shop, the more attentively and persuasively they could be served, and in this sense the design of the shop was very much a part of the sales process.” They made the act of shopping an end, and not just a means.

Trade card advertising a London shop, circa 1758

Some contemporary observers, mostly men, denounced the new shops as palaces of deception, designed to weave a spell over their customers. Describing the new fashionable shops in the resort town of Bath in the early 1700s, Abbé Prévost complained that they took advantage of “a kind of enchantment which blinds everyone in these realms of enjoyment, to sell for their weight in gold trifles one is ashamed of having bought after leaving the place.” In his 1727 survey of British commercial practice, The Compleat English Tradesman, Daniel Defoe devoted an entire chapter to the new practice of outfitting shops with such lavish trappings, a custom that appears to have baffled Defoe: “It is a modern custom, and wholly unknown to our ancestors . . . to have tradesmen lay out two-thirds of their fortune in fitting up their shops . . . in painting and gilding, fine shelves, shutters, boxes, glass-doors, sashes, and the like,” he wrote. “The first inference to be drawn from this must necessarily be, that this age must have more fools than the last: for certainly fools only are most taken with shows and outsides.”

Defoe ultimately decided that there must be some kind of functional motive behind these seemingly excessive displays: “Painting and adorning a shop seems to intimate, that the tradesman has a large stock to begin with; or else the world suggests he would not make such a show.” Defoe’s perplexity here is almost touching: you can see his mind working in overdrive to come up with a logical explanation for the frivolities of fine shelves and sashes. From our modern perspective, we can see clearly how the messaging embodied in the lavish shop decor obviously signaled more than just a large inventory; it created an envelope of luxury and high fashion that elevated the act of shopping itself into a form of entertainment. The consumers flocking to these new commercial spaces weren’t just there for the goods they could purchase. They were there for the wonderland of the space itself.

—

Where shopping for clothes had previously been a straightforward, no-frills series of exchanges, bartering with street vendors or tradesmen— no different from buying eggs or milk—now the practice of browsing and “window shopping” became its own sought-after experience. Before the rise of these lavish London shops, one went to market when one had something specific to purchase. Bazaars and open-air markets existed, of course, but they lacked the sumptuous displays of these new London shops. These “perfectly gilded theaters” transformed the journey of shopping into its own reward. A 1709 contributor to Female Tatler describes the phenomenon—now ubiquitous in the developed world—with fresh eyes: “This afternoon some ladies, having an opinion of my fancy in cloaths, desired me to accompany them to Ludgate-hill, which I take to be as agreeable an amusement as a lady can pass away three or four hours in.”

The language here—“agreeable amusements”—doesn’t fully do justice to the eventual magnitude of the transformation it was describing. It was a subtle shift, hard to notice if you weren’t a proprietor of one of these shops, or a customer. To the untutored eye, those shops seemed like just a minor twist on the peddlers and tradesmen who had sold goods in the city for hundreds of years. In fact, the shift was so subtle that very few records were kept to document its existence. Like so many cultural revolutions that would follow, the modern experience of shopping trickled into the world as a minor subculture, enjoyed by a tiny fraction of the overall population, ignored by the mainstream—until one day when the mainstream woke and found that it had been profoundly redirected by this strange new tributary. Every now and then, the creek floods the river.

The lack of historical records meant that, until recently, most cultural historians assumed that the birth of consumer culture and the sensuous excesses of shop displays began in the late nineteenth century with the invention of the department store, after the first wave of industrialization. But in fact, that traditional story has it exactly backward: the trivial pursuits of shopping were not a secondary effect of the industrial revolution and the rise of bourgeois consumer culture. In several key respects, those elaborate drapers’ shops on the streets of London helped create the industrial revolution. And that is because those gilded theaters were increasingly designed to showcase the brilliantly colored calico prints of a miraculous new material from the other side of the world: cotton.

—

Archeologists believe that the practice of domesticating the plant Gossypium malvaceae, and weaving it into the fabric we now call cotton, dates back more than five thousand years. Interestingly, the manufacture of cotton, using primitive combs and hand spindles, appears to have been independently discovered in four different places around the world, roughly at the same time: in the Indus Valley of present-day Pakistan, in Ethopia, along the Pacific coast of South America, and somewhere in Central America. The utility of Gossypium malvaceae’s fibers seems to become apparent to any sufficiently advanced civilization situated in an ecosystem where the plant naturally lives. Some of those early civilizations failed to invent writing or wheeled vehicles, but they did figure out a way to turn the thin fibers of the cotton boll into soft and breathable fabrics.

Until the 1600s, those fabrics were largely mythical to most Northern Europeans, who dressed themselves in thicker, scratchy garments of wool and linen. Cotton was so fanciful that the globe-trotting British knight John Mandeville famously described in the 1300s “a wonderful tree [in India] which bore tiny lambs on the endes of its branches. These branches were so pliable that they bent down to allow the lambs to feed when they are hungrie.”

But the soft texture of cotton would prove to be only part of its appeal. After thousands of years of experimentation, Indian dyers located on the Coromandel coast established an elaborate system of soaking vibrant dyes like madder and indigo into the fabric, employing lemon juice, goat urine, camel excrement, and metallic salts. Most colored fabrics in Europe would lose their pigment after a few washings, but the Indian fabrics—called chintz and calico—retained their color indefinitely. When Vasco da Gama brought back a cargo full of textiles in 1498 from his landmark expedition around the Cape of Good Hope, he gave Europeans their first real experience of the vivid patterns and almost sensual textures of calico and chintz.

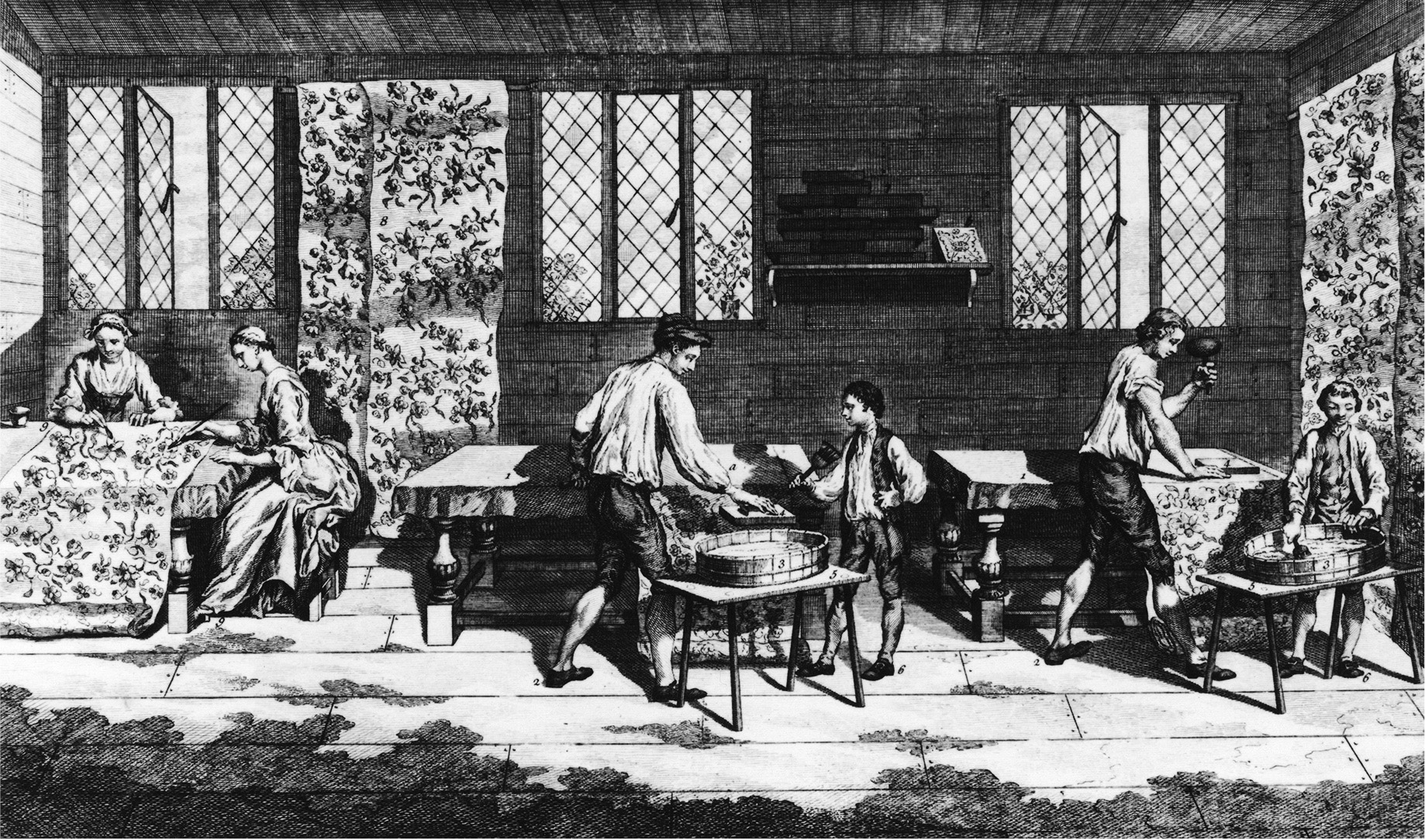

Workers printing and painting calico

As fabrics, calico and chintz first made their way into the routine habits of Europeans through the gateway drug of interior decorating. Starting in the 1600s, the well-to-do of London and a few other European cities began festooning their drawing rooms and boudoirs in the floral or geometric patterns of calico cloth. As clothing itself, cotton was initially perceived to be too light for the climate of Northern Europe, particularly in the winter. But in the final decades of that century, a strange feedback loop began to resonate among the fashionable elite of London society. They began to crave cotton on their bodies. Drapes were cut down and converted into dresses, settees plundered to sew into jackets or blouses. Perhaps most important, cotton undergarments that could be worn in the depths of winter, buffering the skin from the irritations of wool, became an essential element of a lady’s wardrobe.

The surge in interest in Indian textiles was a tremendous boon for the East India Company, which went from importing a quarter of a million pieces in 1664 to 1.76 million twenty years later. (More than 80 percent of the company’s trade was devoted to calico at the height of the craze.) But the news was not as encouraging for England’s native sheep farmers and wool manufacturers, who suddenly saw their livelihoods threatened by an imported fabric. The craze for cotton was so severe that by the first decade of the next century it triggered a kind of moral panic among the rising commentariat, accompanied by a series of parliamentary interventions. Hundreds if not thousands of pamphlets and essays were published, many of them denouncing the “Calico Madams” whose scandalous taste for cotton was undermining the British economy. “The Wearing of printed Callicoes and Linnens, is an Evil with respect to the Body Politick,” one commenter announced. Defoe himself wrote multiple screeds on what he considered “a Disease in Trade . . . a Contagion, that if not stopp’d in the Beginning, will, like the Plague in Capital City, spread itself o’er the whole Nation.” Plays, poems, and popular songs were composed decrying the spread of calico. One song, “The Spittle-Fields Ballad” (which took its name from a neighborhood heavily populated by weavers) took the public shaming to an extreme: “none shall be thought / A more scandalous Slut / Than a taudry Callico Madam.” Rioting weavers marched on Parliament and ransacked the home of the East India Company’s deputy governor. One can safely assume that at no other point in human history have women’s undergarments provoked so much patriotic fury.

Responding to the outrage, Parliament passed a number of protectionist acts, starting with a ban on imported dyed calicos in the 1700s, which left open a large loophole for traders to import raw cotton fabrics, to be dyed on British shores. In 1720, Parliament took the more draconian step of banning calico outright, via “An Act to Preserve and Encourage the Woollen and Silk Manufactures of this Kingdom, and for more Effectual Employing the Poor, by Prohibiting the Use and Wear of all Printed, Painted, Stained or Dyed Callicoes in Apparel, Household Stuff, Furniture, or otherwise.”

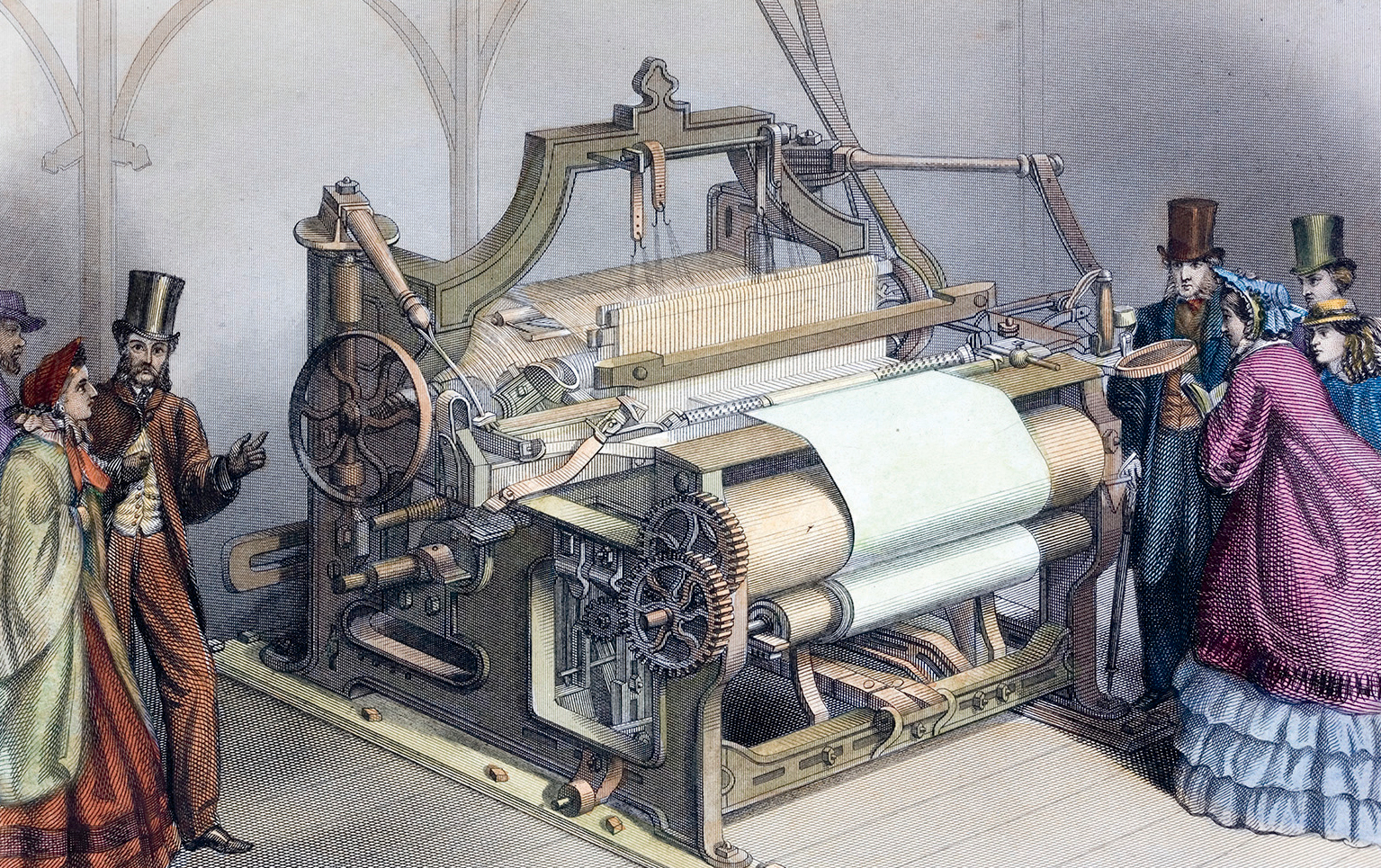

Ironically, the fears that ladies’ fashion trends would undermine the British economy turned out to have it exactly backward. The immense value of the cotton trade had already set a generation of British inventors off in search of mechanical tools that could mass-produce cotton fabrics: beginning with John Kay’s flying shuttle, patented in 1733, followed several decades later by Richard Arkwright’s spinning (or water) frame, then Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, not to mention the endless refinements to the steam engine rolled out during the 1700s, many of which were originally designed to enhance textile production. (Steam engines would eventually power a wide range of industrial production and transportation, but their initial application was dominated by mining and textiles.) Instead of deflating the British economy, the Calico Madams unleashed an age of British industrial and economic might that would last for more than a century.

That cotton changed the world is indisputable. The more interesting question is how this intense appetite for cotton came about. The traditional explanation held that cotton conquered Europe thanks to its intrinsic virtues as a textile and to its price. Yet the historian John Styles has demonstrated that cotton failed to penetrate a true mass market until well into the nineteenth century, and was generally more expensive than the rival products of wool and linen. What set cotton apart was not practical matters of cost and comfort but rather the more ethereal trends of fashion. “The spectacular early triumph of cotton depended most of all on its visual, decorative, fashionable qualities,” Styles writes. “Where appearance was crucial, cotton succeeded. Where utilitarian durability counted, cotton sometimes lagged behind.”

W G Taylor’s Power Loom and Patent Calico Machine

A few perceptive individuals at the time were able to see beyond the Calico Madam protectionist outrage and detect the deeper trends lying beneath the craze for cotton. The economist and financial speculator Nicholas Barbon observed in his 1690 work, A Discourse of Trade: “It is not Necessity that causeth the Consumption. Nature may be Satisfied with little; but it is the wants of the Mind, Fashion and the desire of Novelties and Things Scarce that causeth Trade.” But how did that fashion and that “desire of Novelties” spread through European society? Recall that da Gama first brought calico in bulk to Europe in 1498. Yet almost two centuries passed before a critical mass of people began draping their bodies with it. What caused cotton’s eventual takeoff? This was, of course, an age where advertising and image-based media were literally nonexistent. There were no Vanity Fair spreads or Fashion Week broadcasts to get the word out. You could only experience calico through direct encounters: on the bodies or furniture of people you knew. For a century and a half, that’s how the taste for cotton spread through the population, one banquet at a time. But fads big enough to transform global economies don’t tend to self-organize out of casual gossip. They usually require some kind of amplifier.

Starting in the second half of the seventeenth century, that amplifier appeared on the streets of Ludgate Hill and St. James: those luxurious shopfronts, attracting the eyes of women with enough wealth to spend a few hours browsing for goods that they didn’t, technically, need. Calico had been circulating through Northern Europe for a hundred and fifty years, but it didn’t turn into a true frenzy until the new rituals of shopping—the window displays, the clustered stores, the lavish interiors—had come into being. It’s possible that the news of cotton’s charms simply passed through word-of-mouth networks and slowly built up in intensity. But the historical congruence of those high-end London stores and the calico frenzy of the late 1600s strongly suggests that the Calico Madam was herself the by-product of a new kind of marketplace and the new recreational pastime of shopping. The shopkeepers made the cotton revolution just as much as da Gama did.

The distinction matters because of that standard theory about the rise of “consumer society” and its relationship to industrialization. When historians have gone back to wrestle with the question of why the industrial revolution happened, when they have tried to define the forces that made it possible, their eyes have been drawn to more familiar culprits on the supply side: technological innovations that increased industrial productivity, the expansion of credit networks and financing structures; insurance markets that took significant risk out of global shipping channels. But the frivolities of shopping have long been considered a secondary effect of the industrial revolution itself, an effect, not a cause; a cultural appetite that wouldn’t be whetted until the rise of nineteenth-century department stores like Le Bon Marché and Macy’s. According to the standard theory, industrialization created mechanical processes that greatly reduced the cost of manufacturing and transporting goods, and built up a base of upper-middle-class citizens with enough spare cash to drop on the niceties—which then led to the birth of consumerism. But the Calico Madams suggest that the standard theory is, at the very least, more complicated than that: the “agreeable amusements” of shopping most likely came first, and set the thunderous chain of industrialization into motion with their seemingly trivial pursuits.

This might seem like an academic distinction, but the stakes in this particular wager happen to be high ones. At its core is the question of why big changes in society happen. Are they driven exclusively by new tools and cultural practices that satisfy existential needs, like nutrition, shelter, or sexual reproduction? Or are they also driven by more mercurial appetites? And even if you limit the frame of reference to the Industrial Revolution itself, the story of those luxury stores and the delightful patterns of calico cloth has real weight to it. It strongly suggests that the conventional narrative of industrialization is flawed both in terms of the sequence of events and the key participants. The great takeoff of industrialization, for instance, has inevitably been told as the work of European and North American men—heroes and villains both—building steam engines and factories and shipping networks. But those dyers tinkering with calico prints on the Coromandel coast, creating new designs for the sheer beauty of it; those English women enjoying the “agreeable amusements” of shopping on Ludgate Hill—these were all active shapers of the modern reality of industrialization, as important, in a way, as the James Watts and Eli Whitneys of conventional history.

The account is necessarily murky because so few contemporaries found it necessary to take note of these new shopfronts until the calico craze had threatened to decimate the English economy. And in a way, those omissions were understandable. This was the age of Oliver Cromwell and the Glorious Revolution; larger, more masculine struggles, featuring the traditional agents of world history—kings, armies, priests—were surging across Europe and the British Isles. But with perfect hindsight, if you were sitting there in 1680 trying to predict the massive changes coming to global capitalism, you couldn’t have found a better crystal ball than those calico shops in London.

—

You can still hear the echoes of cotton’s big bang, even in the distant galaxy of contemporary American politics.

During the Cretaceous period, roughly a hundred million years ago, the body of water that eventually drained down to the become the modern Gulf of Mexico covered the southern half of Georgia and Alabama, forming a crescent coastline. The varied marine life that lived in those waters left behind a rich, dark soil. Millions of years after those seas had vanished from the landscape, American farmers discovered those soils were particularly well suited for growing cotton, and a long, curving arc of plantations took root on the scene of that long-forgotten coastline. Starting in the early 1800s, plantation owners forcibly migrated millions of slaves to work what became known as the black belt, a term derived from both the color of the slaves’ skin and the color of the soil itself.

The legacy of that forced migration still lingers: in the 2008 U.S. presidential election, Barack Obama’s support in the south followed almost exactly the distinct crescent of the black belt, thanks to the large number of African-Americans still residing in those counties two centuries later. The ultimate explanation of why Obama won those counties forces us to look beyond the present-tense politics and tell a longer story: from the ancient geological forces that deposited that crescent of black soil, to the appetite for cotton stirred up by the shopkeepers of London, to the brutal exploitation of the plantation system engineered to satisfy that new demand.

The story of calico and chintz is a chilling reminder that the amusements of life have often triggered some of the worst atrocities in history. The sensual delight of these new fabrics inspired a wave of entrepreneurial activity and technological ingenuity, but it also unleashed some of the most destructive forces that the world had ever seen. Cotton dug scars across the face of the earth that are still healing, three hundred years later. The most visible, and painful, of these was slavery in the American south.

Slaves had been a part of the American society from the first decades of the colonial era, but it was cotton that turned the forced labor of African-Americans into the cornerstone of the south’s economy. In 1790, only a handful of counties along the seaboard of the American southeast had a slave population higher than 50 percent, mostly working tobacco plantations. By 1860, slaves made up roughly half of the entire population of the southern states, numbering more than five million in total. The cost of cotton can be measured in military deaths as well. Without its economic dependence on cotton plantations, the south might well have grudgingly acceded to the abolitionist movement, and the Civil War—a war that took as many American lives as all other U.S. military conflicts combined—might have never happened.

Fashion plate from The Lady’s Magazine, 1774

Slavery was cotton’s most appalling legacy, but in the new factories that sprouted first in England and then in the northern states of the United States, the lives of the workers turning the raw cotton into textiles was also horrific: the first years of the industrial age saw decreasing life spans, child-labor abuse, seventy-hour workweeks, air pollution that resembled modern-day Beijing, and the dismantling of many of the conventions of agrarian life.

Between slavery and the grotesque working conditions of early industrialization, one can make the argument that the desire for cotton was the single worst thing to happen to the planet between 1700 and 1900—that it provoked more suffering than any other new development in that period. Those early shoppers savoring the soft fabrics and vibrant patterns of calico at the end of the seventeenth century would have been baffled to know that their fashion decisions were going to unleash such traumatic and deadly forces across the globe.

—

By the end of the eighteenth century, the calico craze—supercharged by the mechanical looms of industrial England—had given birth to the first true fashion “industry.” A woman in 1770s London could enjoy dozens of illustrated periodicals devoted to the latest fabrics or gowns or hairstyles. These publications lacked the snazzier titles of the modern age; instead of Elle or Cosmopolitan, the titles included the Ladies’ Pocket Book; the General Companion to the Ladies, or Useful Memorandum Book; the Ladies’ New and Elegant Pocket Book; the Ladies’ Pocket Journal; and the Polite and Fashionable Ladies’ Companion. (The first full-color fashion image appeared in a publication called The Lady’s Magazine in 1771.) Those magazine titles hint at the complex gender politics of the fashion revolution. On the one hand, women were in many ways the prime movers behind the vast commercial upheaval of the age as advertisers, publishers, textile manufacturers, and financial speculators all set off in pursuit of this strange, seemingly arbitrary need for the latest vogue. On the other hand, the proliferation of guidebooks helped cement an image of female identity that seems, at face value, to be undeniably regressive: that being a woman in modern society entailed tracking the increasingly complex and ever-shifting winds of taste and convention.

Propelled by these publications and by the commercial interests of the manufacturers, the metronome of fashion sped up markedly in the second half of the eighteenth century. As late as 1723, Bernard Mandeville could observe, contemptuously, that most fashion “modes seldom last above Ten or Twelve Years”—a decade-long cycle being a sign of shameful transience. Starting in the 1750s, the pace accelerated to a semiannual rotation, and by the 1770s, fashion more or less stabilized at its current rate of change, where each year introduces a new “in” look. The historians Neil McKendrick, John Brewer, and J. H. Plumb document the change in their groundbreaking work The Birth of A Consumer Society: “In 1753 purple was the in-colour,” McKendrick writes. “In 1757 the fashion was for white linen with a pink pattern. In the 1770s the changes were run even more rapidly—in 1776 the fashionable color was ‘couleur de Noisette,’ in 1777 dove grey, in 1779 ‘the fashionable dress was haycock stain trimmed with fur.’ By 1781 ‘stripes in silk or very fine cambric-muslin’ were in.” For the first time, the cities of Europe—followed, eventually, by the rest of the world—began to be synchronized to a kind of aesthetic clock, with regular pulses of new instructions rippling out from the metropolitan centers: now white linen, now dove gray, now haycock stain. Alongside the ancient rhythms of the seasons, and the more recent emergence of boom-and-bust economic cycles, a new rhythm appeared: the choreographed oscillations of la mode.

Was this, in the end, a good thing? Certainly one can make the argument that fashion compelled a great number of people to spend their days trying to ascertain if their new gown was in fact the correct shade of “couleur de Noisette,” when they might have been attending to more important things. Over time, the social enchantment of fashionable clothes came to envelop almost the entire object world as the advertising trade took the techniques it had developed to sell style and opulence and directed it to more mundane products. The arbitrary linking of status and affluence with shades of fabric—which began in part with Tyrian purple—metastasized into a kind of permanent fantasyland where everything for sale was packaged with a supplementary aura. The British cultural historian Raymond Williams saw this as a form of magical thinking:

It is often said that our society is too materialist, and that advertising reflects this . . . But it seems to me that in this respect our society is quite evidently not materialist enough, and that this, paradoxically, is the result of a failure in social meaning, values and ideals . . . If we were sensibly materialist, in that part of our living in which we use things, we should find most advertising to be of an insane irrelevance. Beer would be enough for us, without the additional promise that in drinking it we show ourselves to be manly, young in heart, or neighborly. A washing-machine would be a useful machine to wash clothes, rather than an indication that we are forward-looking or an object of envy to our neighbors.

But the legacy of the fashion revolution is not just the illusory emotional attachments that have now come to envelop everything we buy, from dresses to phones to pickles. In an important sense, those absurd-sounding garments were a democratizing force. Until the fashion revolution of the eighteenth century, a wide gulf separated the style of the rich and the rest of society. Elaborate fashions, like Tyrian purple, functioned as a kind of decorative shibboleth separating the elites from the common folk. But the manufacturing and advertising businesses that brought those fashions to upper-middle-class ladies in the late 1700s were breaking down an important wall. You could now “pass” for an aristocrat on the street or in the parlor if you paid attention to the signs and symbols circulating through the Lady’s Pocket Book or the Polite and Fashionable Ladies Companion. Today, we don’t blink an eye when some of the richest people in the world dress like your average adolescent skate punk, in hoodies and jeans and old Adidas sneakers. But in the late 1700s, deliberately blurring the semiotics of class was a novel phenomenon, one that seemed to confound expectations about different social stations.

Did blurring the sartorial lines between aristocracy and middle class help usher in the genuine political reform that led to the more egalitarian societies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries? Certainly many conservative observers at the time were convinced that these fashion changes were dismantling the proper divisions between the classes. In 1763, the British Magazine observed the democratization of dress that was under way, and grumbled: “The present rage of imitating the manners of high life hath spread itself so far among the gentle folks of lower life, that in a few years we shall probably have no common folks at all.” Another griped in 1756, “It is the curse of this nation that the laborer and the mechanic will ape the lord; the different ranks of people are too much confounded: the lower orders press so hard on the heels of the higher, if some remedy is not used the Lord will be in danger of becoming the valet of his Gentleman.” The London Magazine warned in 1772 that the “lower orders of the people (if there are any, for the dissections are now confounded) are equally immersed in their fashionable vices.”

In his epic account of the rise of global capitalism, Civilization and Capitalism, Fernand Braudel suggested that the appetite for fashion—despite its apparent superficiality—had unsuspected depth. “Is fashion in fact such a trifling thing?” he asked, in a much-quoted passage. “Or is it, as I prefer to think, rather an indication of deeper phenomena—of the energies, possibilities, demands and joie de vivre of a given society, economy, and civilization? . . . Can it have been mere coincidence that the future was to belong to the societies fickle enough to care about changing the colors, materials and shapes of costume, as well as the social order and the map of the world—societies, that is, which were ready to break with their traditions.” For Braudel, fashion was both a symptom and cause of a certain social restlessness, a willingness to challenge existing conventions. Sometimes those conventions took the form of political or social hierarchies, laws, or voting rights. Sometimes they took the form of a haycock stain trimmed with fur.

Aristide Boucicaut

—

If the eighteenth century encouraged an increasingly democratic model of fashion, the nineteenth century witnessed the creation of a kind of people’s palace in the form of the department store, the immense new spaces that conjured up, for the first time, an entire phantasmagoria of consumption. The origins of the department store are somewhat contested by historians of consumer society: some point to Bainbridge’s in London, others to Alexander Turner Stewart’s “Marble Palace” in downtown Manhattan. But no store from the period captured the imagination of the world like Le Bon Marché, founded by a French fabric salesman named Aristide Boucicaut.

Boucicaut had run a modest shop originally named Au Bon Marché—which means both a “good market” and a “good deal” in French—since 1838, but didn’t begin to dream of a more elaborate enterprise until a visit to the World’s Fair of 1855 suggested to him the seductive power of sensory overload. Boucicaut’s creation would not just be a store outfitted with the trappings of style and luxury, as in those original seventeenth-century shops; it would be an entire wonderland of clothes, fabrics, furniture, trinkets, jewelry, and countless other goods—all collected together in one extravagant space.

Before Le Bon Marché, shopkeepers had competed for the customer’s dollar either by creating organized, efficient spaces where the goods for sale were presented in a coherent display that allowed the customer to acquire what they needed and move on, or they presented a fashionable, luxurious mise-en-scène that gave shopping the allure of an upper-class lifestyle. But Boucicaut was the first to recognize the commercial potential of disorientation and overload. “What’s necessary,” he explained of his customers, “is that they walk around for hours, that they get lost. First of all, they will seem more numerous. Secondly . . . the store will seem larger to them. And lastly, it would really be too much if, as they wander around in this organized disorder, lost, driven, crazy, they don’t set foot in some departments where they had no intention of going, and if they don’t succumb at the sight of things which grab them on the way.”

In this calculated confusion, Boucicaut was adapting one of the classic archetypes of the nineteenth-century city—the flaneur, Baudelaire’s “man of the crowd”—to the emerging customs of mass consumption. The sensory shocks and stimuli of dense urban centers had created a new pastime among aesthetes during this era: the aimless stroll through surging crowds, chattering cafés, and bustling markets of the big city, an experience that Baudelaire likened to a “kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness.” The art of flânerie was, in its way, a kind of urban version of the Romantic sublime; instead of experiencing sensory overload contemplating the majestic peaks of the Matterhorn, one achieved a similar sensibility immersing oneself in the ocean of humanity flowing down the rue du Bac.

Boucicaut recognized that this undirected delight could be channeled to commercial ends, if one created an environment with sufficient sensory excess. And so he set about building a shopping space that would be unlike anything that had come before it, a “cathedral of commerce,” in his own self-congratulatory words. “Dazzling and sensuous, the Bon Marché became a permanent fair, an institution, a fantasy world, a spectacle of extraordinary proportions, so that going to the store became an event and an adventure,” the historian Michael Miller writes. “One came now less to purchase a particular article than simply to visit, buying in the process because it was part of the excitement, part of an experience that added another dimension to life.” Boucicaut’s ambition was so vast that he required new engineering techniques to bring his vision to life. Hiring Gustave Eiffel as his main engineer, Boucicaut built his store around a cast-iron framework topped by enormous skylights, creating oversized galleries illuminated with natural daylight. (The modern shopping experience owes a great debt to materials science and engineering: not just in the form of those cast-iron frames, but also new techniques that allowed giant plate-glass displays to tempt passersby on the sidewalks.) As always, the innovations were all in the service of facilitating consumption: the grand salons enabled large crowds to flow through the store more easily, and gave Boucicaut a massive tableau to stage his extravagant spectacles. Interior balconies allowed visitors to gaze down at the throngs surging through the main floor. By the time of its completion in 1887, the store took up 52,800 square meters, leading many commentators, Boucicaut included, to dub it the eighth wonder of the world. The entrance on the rue de Sèvres was majestically positioned under a cupola, and festooned with caryatids and statues of Roman gods. “The impression was that of entering a theater,” Miller writes, “or perhaps even a temple.”

Temples and cathedrals—religious metaphors abound in descriptions of Le Bon Marché from the period. Perhaps the most famous observer of the department store’s dazzling and disorienting impact was Émile Zola, whose 1883 novel Au Bonheur des Dames tells the story of a Bon Marché equivalent, created by a thinly disguised stand-in for Boucicaut named Octave Mouret. In one famous passage, Zola suggests a kind of zero-sum relationship between the department stores and the churchs themselves:

While the churches were gradually emptied by the wavering of faith, they were replaced in souls that were now empty by [Mouret’s] emporium. Women came to him to spend their hours of idleness, the uneasy, trembling hours that they would once have spent in chapel: it was a necessary outlet for nervous passion, the revived struggle of a god against the husband, a constantly renewed cult of the body, with the divine afterlife of beauty. If he had closed his doors, there would have been a riot outside, the frantic cry of pious women denied the confessional and the altar.

The rhetoric of chapels and cathedrals may seem excessive to the modern ear, but in a way those analogies make sense, given the historical context. We are accustomed now to grand buildings and other planned environments with lavish designs that are open to the general public: shopping malls, theme parks, office buildings, airport terminals. But to a member of the middle class in the nineteenth century, the experience of exploring a space as epic as Le Bon Marché would have been largely unprecedented; the closest equivalent would have been venturing into Notre Dame or St. Paul’s. Grand palaces had existed for centuries, of course, but they were off-limits to ordinary people. Until Le Bon Marché, the only space that offered comparable grandeur to commoners was the church.

Zola’s novel also introduced a narrative device still popular today in both Hollywood movies and the implicit narratives that we draw upon to make sense of social change. The main protagonist, Denise Baudu, is a young woman from the provinces who comes to the city to work at her uncle’s small fabric store near Mouret’s new emporium. She eventually leaves to work for Mouret, and much of the narrative involves her uncle’s battle to stay in business, competing with Mouret’s massive scale and ambition. This struggle would soon become an enduring refrain—the chain store overwhelming the indies and the mom-and-pops—and would form the narrative spine of movies like The Shop Around the Corner and You’ve Got Mail.

Interior of Le Bon Marché, Paris

Le Bon Marché—and its contemporaries in London and New York—helped inaugurate many practices that became commonplace in the next century. The department stores largely killed off the practice of haggling over prices with vendors, replacing that model with high-volume, low-markup sales of goods with fixed prices. Department stores were among the very first institutions to experiment with charge cards that extended their customers a line of credit. (The modern credit card, honored by a wide range of establishments instead of a single store, wouldn’t be invented until the 1950s.) The grand department stores were also the first large organizations focused on the services industry, managing thousands of employees and complex supply chains. Organizations of comparable complexity had emerged in the previous century, but they were inevitably focused on the problems of manufacturing or engineering: building railroads, for instance, or converting raw cotton into textiles. Until Le Bon Marché, the service industry could hardly be considered an industry at all, just a dispersed collection of small shopkeepers, restaurateurs, lawyers, and other miscellaneous trades. Today, three out of four American jobs are in the services sector; by some accounts, the service industry accounts for 80 percent of U.S. GDP. Up until the late 1800s, services seemed like an amusing ornament next to the big business of trade and manufacture, a folly of interest only to a small elite, like the cupola hovering above the rue de Sèvres. Le Bon Marché and its peers hinted, for the first time, that the service industry would soon become a cornerstone.

—

Women, of course, were at the epicenter of this new industry, as they had been during the dawn of the cotton revolution two centuries before. Increasingly, women were working in these new department stores, not just enjoying them as consumers. And just as cotton had unleashed a moral panic over the traitorous desires of the Calico Madam, Le Bon Marché triggered a similar crisis in Parisian society. In this case, it was not women buying luxury items that caused the outrage; it was the even more startling fact that women were stealing them.

Shortly after the arrival of grands magasins like Le Bon Marché, the Parisian authorities and other interested parties began noticing a marked uptick in the number of women caught stealing items from the stores, apparently motivated by some kind of deranged pleasure in the act. “I felt myself overcome little by little by a disorder that can only be compared to that of drunkenness, with the dizziness and excitation that are peculiar to it,” one shoplifter testified. “I saw things as if through a cloud, everything stimulated my desire and assumed, for me, an extraordinary attraction. I felt myself swept along towards them and I grabbed hold of things without any outside and superior consideration intervening to hold me back. Moreover I took things at random, useless and worthless articles as well as useful and expensive articles. It was like a monomania of possession.”

The term kleptomania had been around for several decades as an obscure medical diagnosis, after a wave of predominantly female thieves began pocketing goods from smaller stores in the opening decades of the century. Reading the early essays on the topic is like playing a greatest-hits collection of Victorian clichés: the shoplifter’s malady is attributed to a “lesion of the will,” to hysteria, menstruation, masturbation, and epilepsy. But the 1880s wave of shoplifting at Le Bon Marché and its competitors had elevated the crime to a central topic of conversation in the newspapers and drawing rooms of Paris, and in that elevation a new model for thinking about the human mind and its discontents began to take shape, however tentatively. The shoplifters were extensively studied by the scientific community. The psychiatrist Legrand du Saulle argued that the thefts “constitute a Parisian happening truly and completely contemporary, since they only date from the recent foundation and opening of the grands magasins themselves.” He called the disorder, unforgettably, the department-store disease.

What made the wave of shoplifting particularly alarming—and also somewhat baffling—was the fact that so many of the culprits came from well-to-do households. The thefts were seemingly unmotivated by economic need. Another analysis by the criminologist Alexandre Lacassagne argued that “department store thefts have assumed in our day a real importance because of their growing number, the value and variety of goods stolen, [and] the quality of the persons committing these thefts.” Later he remarked that “most of these kleptomaniacs are only arrested in the department stores. They steal there and nowhere else.” Lacassagne used the department-store disease as a means of challenging the reigning orthodoxy of criminology, founded by the Italian Cesare Lombroso, which contended that criminal pathologies were due to inherited physiological defects. Because the syndrome only emerged with the new environment of the department store, and because the culprits themselves were so obviously of “good breeding,” Lacassagne argued, the roots of the disease must be environmental.

Visible in these perplexed diagnoses is a new way of thinking about the psyche. Diseases of the mind did not have to be rooted in some biological deformity, as the phrenologists had contended; nor was it attributable to some abstract “lesion of the will”; nor was it tied to basic biological realities like menstruation or masturbation. Instead, the root cause of the disorder was to be found somewhere else: in the lived history of social and economic change. Modern life itself could make you sick.

Within a decade, Freud would reroute psychology back toward the eternal truths of Eros and Thanatos, the family romance, and the pleasure principle. But by the second half of the twentieth century, the kind of diagnosis that emerged with the department-store disease would become increasingly familiar. We now assume, correctly or not, that every new media experience is rewiring our brains in some fundamental way; today’s disorders—attention deficit disorder, autism, teen violence—are regularly chalked up to the sensory overload of television, or video games, or social media. We take it for granted that the brain is shaped by the built environment that surrounds it, for better and for worse. That way of seeing the mind—and understanding its occasional defects—first came into view with the unlikely criminals of the department-store disease.

Architects had long constructed environments designed to trigger certain emotional responses in their visitors: think of the soaring interiors of the medieval cathedral, meant to inspire awe and wonder. Boucicaut’s genius—some might call it an evil genius—lay in his realization that built environments could be created to program behavior, to make people want things they didn’t know they needed, to feel desires they had not felt before they entered the wonderland of the grand magasin. But as the kleptomaniacs of the French upper classes made clear, even Boucicaut had no idea just how powerful that program would turn out to be.

—

Follow Route 35 southwest of Minneapolis to the suburban town of Edina, and take the exit onto West Sixty-Sixth Street, and you will eventually find a building complex floating like an island in a gray sea of parking, its exterior a jumbled mix of branded facades: GameStop, P. F. Chang’s, AMC Cinemas. Sixty years ago, when it was first built, the exterior of the building was almost entirely deprived of ornament, the exact opposite of Le Bon Marché’s caryatids and Roman gods. But the design of this structure would define its era every bit as much as Boucicaut’s temple did, for this unremarkable building—practically indistinguishable from the shopping complexes and office parks that surround it on all sides—is Southdale Center, America’s first mall.

Today malls have a mostly well-deserved reputation for being the ugly stepchild of consumer capitalism, but their intellectual lineage is more complex than most people realize. While it would come to epitomize the cultural wasteland of postwar suburbia, the shopping mall turns out to have been the brainchild of an avant-garde European socialist named Victor Gruen. Born in Vienna around the turn of the century, Gruen grew up, as his biographer M. Jeffrey Hardwick put it, “in the dying embers of [Vienna’s] vibrant, aesthetic life.” He studied architecture at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, working under the socialist urban planners then in vogue, and performing in cabarets at night. He built up a fledgling practice designing storefronts on the fashionable streets of Vienna, not unlike the original merchants in Ludgate Hill so many years before, and he designed—but never built—one large-scale project for public housing, which he dubbed “The People’s Palace.” Like many left-wing Jewish intellectuals, Gruen fled to the United States as the Nazis began marching across Europe. (He left Vienna the same week Sigmund Freud did.) He arrived in the United States not speaking a word of English, but by 1939 he was performing with a theater troupe in Manhattan and designing boutiques on Fifth Avenue. He developed a signature style in the shop designs, with open-air arcade entrances flanked by giant plate-glass displays arrayed with goods. The new storefronts delighted consumers and merchants alike, though critics like Lewis Mumford grumbled that the facades captured their customers the way “a pitcher plant captures flies or an old-style mousetrap catches mice.” During the 1940s, Gruen’s design practice boomed; he built dozens of department stores across the country. Echoing Le Corbusier’s famous line about a house being a “machine for living,” Gruen began calling his store environments “machines for selling.”

Victor Gruen

Yet Gruen never fully left his Viennese radical upbringing and its faith in the potential of large-scale planned communities. He hated the noisy, crass commercialism of unregulated spaces. He had an urbane European’s disdain for American suburbia. In the late 1950s, Gruen gave a speech in which he denounced the banal landscapes of the postwar suburbs, calling them “avenues of horror . . . flanked by the greatest collection of vulgarity—billboards, motels, gas stations, shanties, car lots, miscellaneous industrial equipment, hot dog stands, wayside stores—ever collected by mankind.” Gruen was a complicated mix: a socialist who despised the aesthetics of unchecked capitalism, who nevertheless designed department stores for a living. His job description was almost as hard to classify as his values. A mix of architect, urban planner, and interior decorator, Gruen eventually began calling himself an “environmental designer,” a phrase that Boucicaut would have understood in an instant.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Gruen began exploring more ambitious designs that would incorporate multiple stores and other public spaces. He designed a hugely successful open-air shopping plaza in the suburbs of Detroit called Northland Center. But it was in 1956 that Gruen completed work on Southdale Center, which would become his most famous—and, to some, notorious—project. Gruen designed Southdale as a two-level structure linked by opposing escalators, featuring a few dozen stores arrayed around a shared courtyard, protected from the harsh Minneapolis weather by a roof. Gruen modeled the building after the European arcades that had flourished in Vienna and other cities in the early nineteenth century. But to modern eyes, the reference to European urbanity is lost: Southdale Center is, inescapably, a shopping mall, the first of its kind to be built.

Southdale Center, America’s first mall

Southdale was an immediate hit, attracting almost as much coverage and hyperbolic praise as Walt Disney’s reinvention of the amusement park. “The strikingly handsome and colorful center is constantly crowded,” Fortune announced. “The sparkling lights and bright colors provide a continuous invitation to look up ahead, to stroll on to the next store, and to buy.” Ecstatic photo essays appeared everywhere from Life to Time to Architectural Forum, the latter of which described Southdale as “more like downtown than downtown itself.” Most commentators focused on the expansive courtyard space, which Gruen had dubbed the “Garden Court of Perpetual Spring,” where shoppers could enjoy sculptures, children’s carnivals, cafés, eucalyptus and magnolia trees, birdcages, and dozens of other diversions. Interestingly, one of the few dissenting voices came from Frank Lloyd Wright, then nearing ninety years of age, who complained that the garden court “has all the evils of a village street and none of its charms.”

Gruen’s design for Southdale would become the single most influential new building archetype of the postwar era. Just as Louis Sullivan’s original skyscrapers had defined the urban skylines of the first half of the twentieth century, Gruen’s shopping mall proliferated around the globe, first in suburban American towns newly populated by white flight émigrés from metropolitan centers. Shopping meccas like L.A.’s Beverly Center became cultural landmarks, and the default leisure activity of hanging at the mall would define an entire generation of “Valley girls.” But as mall culture went global, Gruen’s design became increasingly prominent in the downtown centers of new megacities. Originally conceived as a way to escape the harsh winters of Minnesota, Gruen’s enclosed public space accelerated the mass migration to desert or tropical climates made possible by the invention of air-conditioning. Today, the ten largest shopping malls in the world are all located in non-U.S. or European countries with tropical or desert climates, such as China, the Philippines, Iran, and Thailand. And while the mall itself would expand in scale prodigiously—a mall in Dubai has more than one thousand stores spread out over more than five million square feet of real estate—the basic template of Gruen’s design would remain constant: two to three floors of shops surrounding an enclosed courtyard, connected by escalators.

But there is a tragic irony behind Gruen’s seemingly massive success. The mall itself was only a small part of Gruen’s design for Southdale and its descendants. Gruen’s real vision was a for a dense, mixed-use, pedestrian-based urban center, with residential apartments, schools, medical centers, outdoor parks, and office buildings. He later expanded his vision of the new city in an eclectic series of planning briefs, speeches, and essays, culminating in a book called The Heart of Our Cities. The spectacle of the mall courtyard, and its pedestrian convenience, was for Gruen a way to smuggle European metropolitan values into a barbaric American suburban wasteland. According to Gruen’s original design, as Malcolm Gladwell writes, “Southdale was not a suburban alternative to downtown Minneapolis. It was the Minneapolis downtown you would get if you started over and corrected all the mistakes that were made the first time around.” Even the ultimate defender of traditional downtown sidewalks, Jane Jacobs, was smitten by Gruen’s designs. Describing an ambitious plan for a new Fort Worth that Gruen had developed but never built, Jacobs wrote, “The service done by the Fort Worth plan is of incalculable value, [and will] set in motion new ideas about the function of the city and the way people use the city.”

Yet developers never took to Gruen’s larger vision: instead of surrounding the shopping center with high-density, mixed-use development, they surrounded it with parking lots. They replaced Gruen’s courtyard carnivalesque with food courts. Communities did blossom around the new malls, but they were largely uncoordinated developments of low-density single-family homes. The suburbs had always been safer and more family-friendly than city centers, but Gruen’s shopping mall held out the promise that they might also be exciting in the way that Fifth Avenue or the Miracle Mile was exciting. Of course, suburbanization had many winds in its sails, but Gruen’s shopping mall was undeniably one of the strongest. Southdale was going to be the antidote to suburban sprawl. Instead it became an amplifier.

And here is where the story turns dark. The mall didn’t just help create the modern, postwar suburb, it also helped undermine the prewar city. The mass exodus from urban centers in Detroit and Minneapolis and Brooklyn and dozens of other U.S. cities precipitated the urban crises of the 1960s. No affliction is more devastating to the life cycles of a big city than sudden population loss. Race riots, exploding crime rates, abandoned neighborhoods, and budget crises convinced many reasonable Americans that big cities were either confronting total collapse, or were doomed to live in a permanent state of anarchy. Those eulogies for the city turned out to be premature, and today it is the old downtown that is drawing shoppers and strollers and flaneurs away from the mall. But for a few decades there, it was touch and go. It is no accident that cities like Detroit that are still struggling to climb back from the urban collapse of the 1960s were also the ones where Gruen’s designs first took root. Even his cherished Vienna, he discovered on returning to the city in the early 1970s, had been threatened by what a he called a “giant shopping machine” built on the outskirts of the city, imperiling the small, independent stores within the city center. Gruen would eventually renounce his creation, or at least the distorted version of it that the mall developers had implemented: “I refuse to pay alimony,” he proclaimed, “for these bastard developments.”

—

As the shopping-center developers were happily ignoring Gruen’s plans for reinventing the city, his ideas nonetheless managed to attract one devoted fan who had the financial resources to put them into action: Walt Disney. The 1955 launch of Disneyland had been a staggering success for Disney. No one had ever built a theme park with such attention to detail, a fantasy space that enveloped the visitor, a perfect cocoon of wonder and amusement. But the triumph of the planned environment inside the park itself created a kind of opposing reaction in the acres outside, which were swiftly converted from orange groves into cheap motels, gas stations, and billboards. Disney grew increasingly repulsed by the blight of highway sprawl that surrounded his crown jewel. And so he began plotting to construct a second-generation project in which he could control the whole environment—not just the theme park but the entire community around it.

In what was going to be the ultimate act of imagineering, Disney planned to design an entire functioning city from scratch, one that would reinvent almost every single element of the modern urban experience. He had dubbed it EPCOT, short for Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow. While the Disney Corporation would eventually build a future-themed amusement park called EPCOT in Orlando, it had virtually nothing to do with Disney’s vision for EPCOT, which would have been a true community with full-time residents, not another tourist attraction. In his career, Disney had radically reinvented multiple forms of entertainment, from animated features to amusement parks. But his final act was going to be even more ambitious: reinventing urban life itself.

The legend that has accumulated around Disney’s epic goals for EPCOT largely fits with the historical facts. In the 1966 film introducing Disney World, Disney spends almost no time discussing the amusement-park component of the project (what would eventually become the Magic Kingdom). Instead, he focuses extensively on his “city of tomorrow,” showing prototypes and sketches that look strikingly like the futurist cityscapes imagined by Le Corbusier almost fifty years before. But the legend of Walt’s avant-garde urban planning has a strange twist to it, one that has received less coverage over the years. In preparation for the EPCOT project, Disney went on a national tour of visionary, cutting-edge experiments in planning and community design, seeking inspiration for his own radical new city. What were the primary sacred sites for such a pilgrimage? Two shopping malls on the East Coast, as well as a new Neiman Marcus department store in Texas.

The gap between Disney’s ambition and his prior art seems a little baffling to us now, like someone setting out to reinvent the literary novel by studying the Great Works of Nicholas Sparks. But the fact is, Disney’s expedition made a certain kind of sense: the shopping mall was, in the early 1960s, a new kind of planned environment, one that would have a tremendous impact on social organization in the decades to come. Like it or not, it was a crystal ball. If you wanted to understand something important about the way human beings would live in the year 2000, studying shopping malls was probably about as good a clue as anything going in the early 1960s.

During his exploratory research, Disney fell under the spell of Gruen. Gruen had included some kind words about the planned environment of Disneyland in The Heart of Our Cities, and predictably shared Disney’s contempt for the sprawling “avenues of horror” that had proliferated around the theme park in Anaheim. And so when Disney decided to buy a vast swath of swampland in central Florida and build from scratch a “Progress City,” as he originally called it, Gruen was the perfect patron saint for the project.

In 1966, Disney set up a Skunk Works operation on their Burbank lot, in a lofty space that was quickly dubbed “The Florida Room,” where a team of imagineering urban planners labored over mock-ups of their new city. Disney apparently kept a copy of The Heart of Our Cities on his desk. For months, the existence of the room was top secret, even to Disney insiders. (The secrecy derived in part from the fact that Disney had to purchase most of the Florida land parcels anonymously to keep the price low.) But once word leaked of the Orlando site, Disney decided to open the doors to the Florida Room and to the project it was incubating. In the late summer of 1966, he made a thirty-minute film introducing Disney World that featured dazzling footage of the twenty-foot maps covering the Florida Room’s oversized walls. (Draftsmen are seen climbing ladders, presumably adding some intoxicating new detail to one of the maps.) A kind of aura has developed around the film among Disney cognoscenti, because it turned out to be the last film that Walt Disney ever made. (He was already terminally ill with cancer during the filming.) But it is more interesting to us today as a glimpse of what Disney might have built had he not died.

The film makes it abundantly clear how central the EPCOT project was to Disney. Standing in front of an oversized map of the entire project, Disney spoke of his ambitions in his usual avuncular manner:

The most exciting, by far the most important part of our Florida project—in fact, the heart of everything we’ll be doing in Disney World—will be our experimental prototype city of tomorrow . . . EPCOT will take its cue from the new ideas and new technologies that are now emerging from the creative centers of American industry. It will be a community of tomorrow that will never be completed, but will always be introducing, and testing, and demonstrating new materials and new systems. And EPCOT will always be a showcase to the world of the ingenuity and imagination of American free enterprise. I don’t believe there is a challenge anywhere in the world that’s more important to people everywhere than finding solutions to the problems of our cities.

The first thing that should be said about EPCOT is that, like Gruen’s original plan for Southdale, it was going to be an entire community oriented around a mall. “Most important, this entire fifty acres of city streets and buildings will be completely enclosed,” a narrator explains in the 1966 film. “In this climate-controlled environment, shoppers, theatergoers, and people just out for a stroll will enjoy ideal weather conditions, protected day and night from rain, heat and cold, and humidity.”

Early models for EPCOT’s World Showcase. The designs reflect traces of Disney’s original plan to build a centrally organized pedestrian city.

The vision of a radical new model of urbanism with a shopping mall at its core is enough to produce snickers from the modern urbanist, for good reason. Yet the EPCOT plan had a complexity to it that we should not forget, a complexity that no doubt derived from the contradictions in Gruen’s philosophy. It was, for starters, profoundly anti-automobile. At the center of the city was a zone that Gruen had come to call the Pedshed, defined by the “desirable walking distance” of an average citizen. Cars would be banned from the entire Pedshed area. As one moved away from the central core, new modes of transportation would appear, each appropriate to the distance required to get EPCOT residents downtown: the electric “people movers” that now take tourists around Disney World’s Tomorrowland would shuttle residents from the high-density apartments to the commercial core; longer trips to and from the lower-density residential developments and industrial parks at the edge of the city would be conducted via monorail. Just as in Disney’s theme parks, all supply and service vehicles would be routed below the city through a network of underground tunnels. In the film, the narrator happily explains that EPCOT residents would use their cars only on “weekend pleasure trips.”

The tragic contradictions of Gruen’s life run through the plan for EPCOT as well: watching Disney’s film, you catch a fleeting glimpse of an alternate version of the recent past, where the pedestrian mall—“more like downtown than downtown itself”—inspires a new vision of urban life that rejects the tyranny of the automobile and ushers in a new era of mass-transit innovation. (Just imagine the impact on climate change if we’d had thirty years of using our automobiles only for weekend pleasure trips.) But, of course, that alternate past didn’t happen. Instead, the mall triggered decades of suburban ascendancy, and the Walt Disney Corporation turned EPCOT into yet another theme park, with its bizarre and sad hybrid of Buckminster Fuller futurism and It’s-a-Small-World globalism.

Why weren’t progress cities built? The easiest way to dismiss the Gruen/EPCOT vision is to focus on the centrality of the mall itself. Now that mall culture is in decline—in the United States and Europe at least—we understand that the overly programmed nature of the mall environment ended up being its fatal flaw. As always, play is driven by surprise and novelty, just as it was when those London ladies first encountered the lavish shopfronts of Ludgate Hill, or when the Parisian kleptomaniacs first wandered into the wonderland of Le Bon Marché. One of the reasons the critics raved over Gruen’s original Southdale Center was the simple fact that no one had seen a space like that before, particularly in suburban Minnesota. But as the developers standardized Gruen’s original plan, and as the big chain stores grew more powerful, malls became interchangeable: a characterless cocoon of J.Crew and the Body Shop and Bloomingdale’s. They were not quite “avenues of horror” but something equally soulless: avenues of sameness. Eventually, our appetite for novelty and surprise overcame the convenience and ubiquity of mall culture, and people began turning back to the old downtowns. Those downtowns were dirty and crowded and open to the elements, but they were also unpredictable and unique and fun in a way that the mall could never be.

Disney and Gruen wanted the energy and vitality and surprise of the big city, without all of the hassle. It turns out that a little bit of hassle is the price you pay for energy and vitality. But I suspect the mall at the epicenter of Southdale and EPCOT is too distracting a scapegoat: dismissing EPCOT as a crowning moment in the history of suburbanization—the city of the future is built around a mall!—diverts the eye from the other elements of the plan that actually have value. The fact that Jane Jacobs, who had an intense antipathy to top-down planners, saw merit in the Gruen model should tell us something. It would be fitting, in a way, if some new model of urban organization emerged out of a shop-window designer’s original vision, given the roots of the industrial city in the lavish displays of the London shops. Routing services belowground; clearing out automobiles from entire downtowns; building mixed-use dense housing in suburban regions; creating distinct mass-transit options to fit the scale of the average trip—these are all provocative ideas that have been explored separately in many communities around the world. But, to this day, no one has built a true Progress City, which means we have no real idea how transformative it might be to see all these ideas deployed simultaneously. Mall or no mall, perhaps it’s time we tried.