3

Taste

The Pepper Wreck

Deep history can usually be detected in the most banal of artifacts, if you know where to look. Consider one of the most derided items on a modern supermarket shelf: the humble Doritos chip. Originally introduced in 1964 as an exclusive treat for Disneyland visitors, showcased at the “Casa de Fritos” in Adventureland, Doritos have become the crown jewel in the Frito-Lay empire of snacks. Since that amusement-park debut, the Doritos family has diversified into a wide range of flavors and cobranding opportunities: Cool Ranch, Sour Cream and Onion, Taco Bell’s Taco Supreme, Pizza Hut’s Pizza Cravers, Nacho Chipotle Ranch Ripple, Four Cheese, Spicy Nacho. Like every food sold in America since 1990’s Nutrition Labeling and Education Act, the packaging of Doritos contains, in near-microscopic print, a list of all the ingredients used to produce the chips:

Whole corn, vegetable oil (corn, soybean, and/or sunflower oil), salt, cheddar cheese (milk, cheese cultures, salt, enzymes), maltodextrin, whey, monosodium glutamate, buttermilk solids, Romano cheese (part skim cow’s milk, cheese cultures, salt, enzymes), whey protein concentrate, onion powder, partially hydrogenated soybean and cottonseed oil, corn flour, disodium phosphate, lactose, natural and artificial flavor, dextrose, tomato powder, spices, lactic acid, artificial color (including Yellow 6, Yellow 5, Red 40), citric acid, sugar, garlic powder, red and green bell pepper powder, sodium caseinate, disodium inosinate, disodium guanylate, nonfat milk solids, whey protein isolate, corn syrup solids.

All those ingredients, assembled to produce a two-dollar bag of snack food. Put aside all the chemistry-lab mystery ingredients we associate with processed junk food—sodium caseinate, disodium inosinate, disodium guanylate—and consider just the ingredients you actually recognize as food. Every Doritos chip offers a reminder of how globally intertwined our food networks have become. We think of Frito-Lay products as the ultimate highway convenience-store nonfood, but in a way, they are true citizens of the world. Corn was originally domesticated as maize in Mexico; soybeans first took root as an ancient East Asian crop; sunflowers were mostly native to North America; cheddar cheese was first crafted in England, while Romano comes from Italy. The milk in buttermilk and other cheeses dates back to the first cows that were domesticated for milk in Southwest Asia ten thousand years ago. No one knows for sure where onions first originated, but they are likely as old as agriculture itself. While we think of tomatoes as staples of the cuisines of Spain and Italy, the tomato plant first grew in the Andes of South America. Sugarcane hails from Southeast Asia, garlic came from Central Asia, and red and green pepper were native to Central and South America.

An entire planet’s worth of flavors converge every time you savor the tangy, sharp taste of that Doritos chip. How did this globalized palate first come into being? The answer to that question is right there on the Doritos’ packaging, in the most enigmatic item on the ingredients list: spices.

—

Roughly three hundred kilometers east of the Indonesian mainland lies a string of small, tropical islands, verdant volcanic cones that formed only ten million years ago. Today, geologists understand that they reside at a unique position on the planet’s surface: the only place on Earth where four distinct tectonic plates converge. Formally, they are called the Maluku archipelago, but the five islands at the northern tip of the archipelago—Ternate, Tidore, Moti, Makian, and Bacan—have long been known by another name: the Spice Islands. Until the late 1700s, every single clove consumed anywhere in the world began its life in the volcanic soil of those five islands.

Despite their remote location and diminutive size, the islands have served as nodes on a global network of trade for at least four thousand years. Archeologists in Syria have found cloves preserved in ceramic pottery at the Old Babylonian site of Terqua, dating back to 1721 BCE. We think of the spice trade as a practice that belongs to the Age of Exploration, but its roots are far older. Somehow, in an era before compasses, accurate cartography, or printing presses, word had spread across the planet of the clove’s alluring taste and aroma, and a network of trade had assembled to transport these tiny flower buds six thousand miles, from the Molucca Sea to the banks of the Euphrates.

The sheer scale of the transportation network that brought the cloves to Syria seems almost impossible given the navigational limitations of the age. A Babylonian living two thousand years before Christ would have had no idea about the existence of the Spice Islands, or Indonesia—or the Indian Ocean for that matter. Put another way, those tiny spices traveled thousands of miles farther than any individual human had ever traveled. The epic relay race that brought the cloves to modern-day Syria is lost to us now, but our knowledge of spice-trade routes from Roman times suggests the broad outlines of the itinerary. Outriggers or Chinese traders would have carried the cloves down through the Java Sea, winding their way through the narrow straits of Malacca. At port cities in Sumatra or modern-day Malaysia, they would have been sold to Indian traders who brought them across the Bay of Bengal around Sri Lanka to the Malabar coast of India. There Arab ships would have transported them up through the Persian Gulf, off-loading them to desert caravans whose camels would pull the cloves across modern-day Iraq to the kitchens of Babylon.

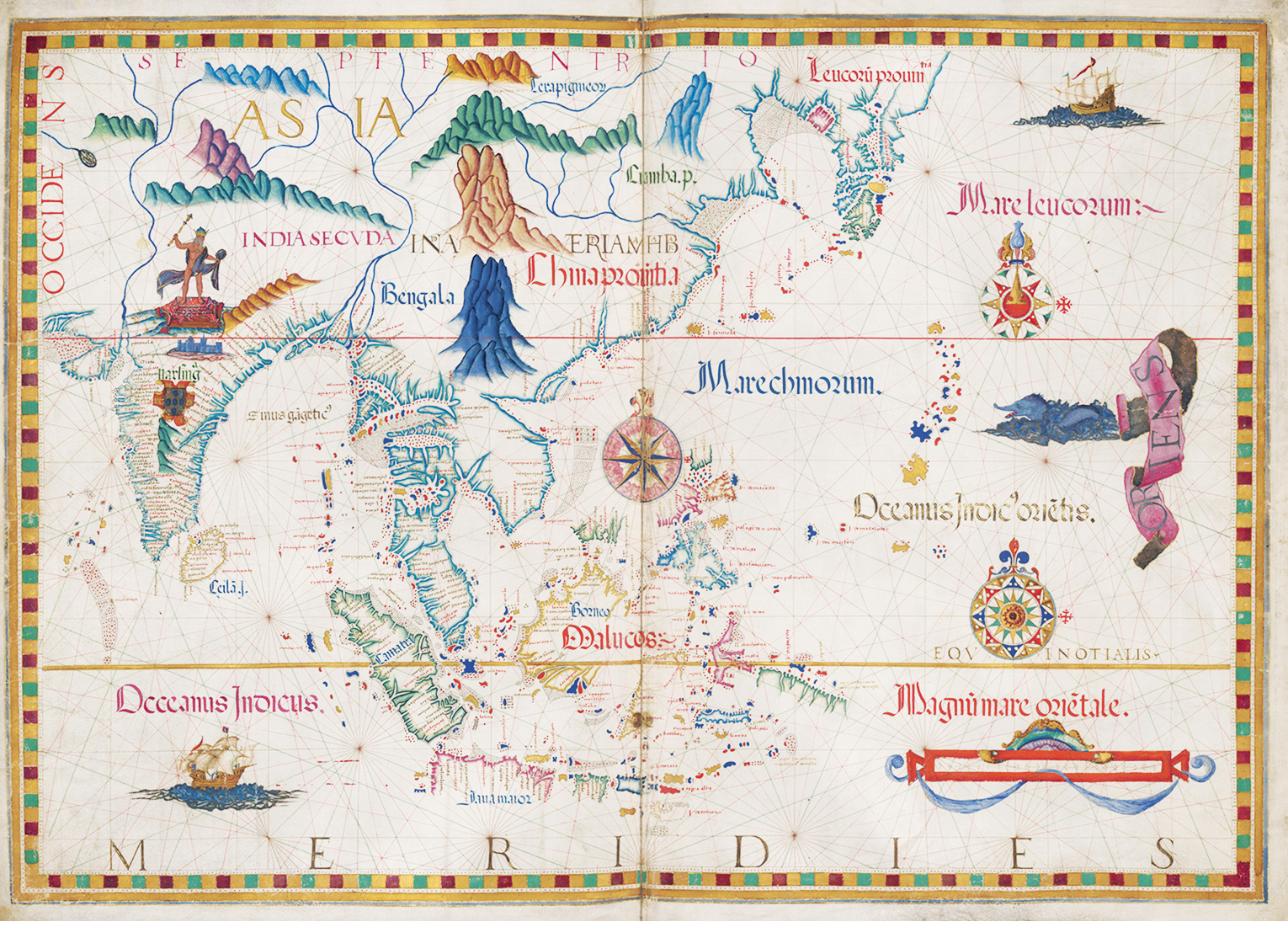

Map of the Spice Islands

The first group to replace that distributed network of local traders with a single integrated global system were the Muslim traders who came to prominence in the seventh century CE. The new regime did away with the regional intermediaries, creating a massive and unified market that stretched from the Indonesian archipelago to Turkey and the Balkans all the way across sub-Saharan Africa, following the Senegal and Niger rivers. Muslim traders worked the entire length of this vast system, and their interactions with local communities introduced more than just a taste for cloves; they also brought Islam to these regions of the world. In almost all the places where Muslims attempted to convert local communities through military force—Spain or India, for instance—the Islamic faith failed to take root. But the traders turned out to be much more effective emissaries for their religion. The modern world continues to be shaped by those conversions more than a millennium later. The map of the Muslim spice trade circa 900 CE corresponds almost exactly to the map of Islamic populations around the world today. Indeed, it is entirely possible that Islam would not have become a major global religion without the long reach of the spice traders’ integrated network. The geography of Islam in the twenty-first century is, in effect, the afterimage of a much earlier map: places where Muslims turned a profit introducing delightful new flavors to the taste buds of consumers.

The clove was not the only botanical jewel produced by the islands east of Indonesia. South of the Malukus, an even smaller archipelago known as the Banda Islands, with a combined landmass of only seventeen square miles, was the exclusive home of the nutmeg tree until modern times. The archipelago included two islands, Pulau Ai and Pulau Run, historically anglicized as Puloway and Puloroon. The latter island is so small one would be hard-pressed to fit a regional airport on its soil, and yet, at the height of the spice trade, James I formally referred to himself as “King of England, Scotland, Ireland, France, Puloway and Puloroon.” A few decades later, the British would surrender their holdings in the Bandas to the Dutch, in return for a slightly larger, but less botanically unique, island on the other side of the world: Manhattan.

Engraving of nutmeg, circa 1798

When Columbus returned triumphantly in 1493 to announce to the Spanish court that he had succeeded in finding a westward passage to the Orient, he brought back three main pieces of evidence to support his claim: parrots, a small retinue of Caribbean natives that he mistakenly called Indians—and cinnamon. (In the end, he was as wrong about the cinnamon as he was about the Indians; the spice turned out to be the bark of an unrelated Caribbean tree and tasted almost nothing like cinnamon.) Risking one’s life and vast amounts of money to sail across an uncharted globe—all in pursuit of condiments? It seems almost comical to us now. But while the taste for spice may seem frivolous to us today, that desire—appetite is the wrong word for foodstuffs with such limited nutritional value—is the origin point for the cosmopolitan mélange of flavors baked into that Doritos chip, not to mention the international melting pot that is every modern supermarket. More than that, the seeds and buds of cloves, cinnamon, and nutmeg were also the seedlings out of which the whole idea of a global marketplace first sprouted. As the historian Jack Turner writes in his authoritative account, Spice: The History of a Temptation, “Nowhere is the history of East and West more incestuous than at the table. For the sake of spices East and West had an ancient relationship. In light of the appearance of spices in the most remote periods, it is a reasonable possibility that it was because of spices that they first met.” And no spice did more to transform the planet than the one that now graces every dining room table, so ubiquitous that it is often distributed for free: pepper.

—

In September of 1606, a Portuguese cargo ship named the Nossa Senhora dos Martires arrived at the mouth of the Tagus River, not far from Lisbon. The ship was returning from a nine-month voyage, its hulls filled with a small fortune of goods brought back from India. But before the Nossa Senhora dos Martires could make her way to the Lisbon anchorage through the dangerous northern channel of the Tagus, the wind fell and she was dragged against the rocks of the São Julião da Barra promontory. The intensity of the collision and the heavy winds caused the structure of the ship to fail catastrophically. The ship settled into the riverbed in pieces near the newly constructed fortress of São Julião da Barra, where she remained for almost four centuries.

As the years passed, the legend of a sunken treasure in the shadow of São Julião da Barra grew. Scuba divers began exploring the area in the 1950s and caught glimpses of a ship’s hull buried in the silt. In 1996, the Portuguese Museum of Archeology sponsored an excavation of a one-hundred-square-meter site where a large section of the hull had settled. The promise of a vast hoard of treasure turned out to be myth: the archaeologists recovered pieces of Burmese stoneware, porcelain, and a handful of gold and silver coins. But the real treasure of the Nossa Senhora dos Martires was plain to see: the coins and trinkets and pottery lay buried beneath a dark blanket of peppercorns.

Worthless to a modern treasure hunter, the peppercorns would have been worth millions had the Nossa Senhora dos Martires made it to safe harbor in Lisbon. When the ship sank back in 1606, it left behind a black tide of peppercorns that washed ashore on the banks of the Tagus, where they were eagerly scavenged by local residents who flocked to the riverside to collect the spice. Today, the “Pepper Wreck”—as it has come to be called—is a startling reminder of just how valuable this now-quotidian spice was during its prime. During the Middle Ages, a pound of pepper was at many points worth more than a pound of gold. (Today a pound of gold will set you back almost $20,000, while a pound of pepper can be acquired for around five dollars.) Peppercorns were regularly used as a form of payment, serving as a kind of “universal currency,” as Turner calls them. The custom of paying (or supplementing) one’s rent with a few pounds of pepper continued in parts of Europe until the 1900s. When the Portuguese queen Isabella married in 1526, a significant portion of her dowry came in the form of peppercorns.

Divers raise a section of the “Pepper Wreck”’s keel

No civilization in history went as insane over spices as the Roman Empire. An average meal served at a banquet for the Roman elites would include an entire spice rack’s worth of flavoring. Apicus’s Cookbook from the first century CE features pepper prominently in 80 percent of its recipes, including “a variety of spiced desserts such as a peppered wheat-flour fritter with honey or a confection of dates, almonds, and pine nuts baked with honey and a little pepper.” Fittingly, when the Barbarians laid siege to Rome in 408 CE, their leader, Alaric the Goth, offered to call off the blockade in return for a bounty of gold, silver, silk, and three thousand pounds of pepper. That may sound absurd—like asking for a bounty of plastic forks and paper napkins—but the Roman taste for spice had momentous consequences. Some historians believe that the Roman trade deficit with India—consisting in large part of pepper imports—played a critical role in triggering the fall of the empire itself. In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder noted, “There is no year in which India does not drain the Roman Empire of fifty million sesterces.” The legendary decadence of the late Roman Empire wasn’t just about moral decline; those spice-laden feasts had economic costs as well.

If pepper helped trigger the collapse of one of Europe’s great cities, it helped build others. A modern visitor to the canals of Venice or Amsterdam, admiring the palazzos along the Grand Canal or the elegant town houses ringing the Herengracht, would do well to pause for a moment and consider that much of this worldly sophistication was originally funded by spices. Venice became the central European distribution point for pepper and other spices in the mid-thirteenth century, after Muslim traders had brought the spices to the Adriatic from India in caravans. The profits Venice made from the sale of its legendary Murano glass were an afterthought compared to the tariffs it charged as a middleman in the spice trade. By the 1600s, the direct sea routes to India had already started to lower the price of pepper on the open market, though it was still precious enough to inspire a new age of empires and global corporations. The Dutch East India Company—the very first corporation to issue publicly traded stock—was founded to exploit the immense profitability of the spice trade. Modern economists estimate that the Dutch markup on nutmeg and clove was as much as 2,000 percent.

The taste for pepper and other spices also provoked some of the darkest chapters in the history of globalization. The British East India Company instituted a virtual slave colony on the island of Sumatra to increase the productivity of its pepper vines there. In the late 1600s, the Dutch began trading opium grown in India in return for Indonesia pepper, triggering a plague of addiction that would last for centuries. An English trader wrote in 1711, “The Mallayans [now Malaysians] are such admirers of opium that they would mortgage all they hold most valuable to procure it.” A century later, American traders would embrace the same brutal tactics. “Nothing is more certain than that opium brings generally 100 percent [profit] when sold to the Malays in Barter,” an American merchant named Thomas Patrickson wrote to a friend in 1789, “and no reason can be alleged against visiting the Malay Coasts except Danger.”

In terms of sheer brutality, few regimes in the history of the spice trade rival the Dutch domination of the Spice Islands that began in the early 1600s. When the Bandanese population had the audacity to challenge the suggestion that a handful of Europeans should have exclusive rights to the islands’ bounty, the Europeans went into a fury of mercantilist genocide that was breathtaking in its speed and efficiency. In what the historian Vincent Loth called “one of the blackest pages in the history of Dutch overseas expansion,” the Dutch, led by Governor-General Jan Pieterszoon Coen, managed to kill thirteen thousand Bandanese natives of the island Lonthor in a few weeks of organized savagery. Coen brought in Japanese mercenaries to assassinate the Bandanese elite, forty of whom were decapitated, their heads displayed on spikes to stifle further dissent. In a matter of decades, the indigenous population of the Bandas had vanished from the islands, most of them murdered. In their place, the Dutch imported slaves and convicts to work the plantations, creating vast riches for the Dutch East India Company. Whatever your opinion of the modern multinational corporation may be, it is an undeniable fact that the institution’s early roots were nourished by the blood of human beings, first in the Spice Islands and then in the slave plantations of the Caribbean, the American South, and other tropical locales that happened to be cursed with good soil, regular rains, and abundant sunshine.

The first Dutch ship in the East Indies, 1596 (circa 1870 by Van Kesteren)

The brutality of the Dutch regime—and their determination to maintain a complete monopoly on the world’s supply of cloves and nutmeg—would eventually come back to haunt them. By the mid-1620s, the Dutch had negotiated and slaughtered their way to complete control of the islands where these lucrative plants grew. But that dominance eventually provoked more than a few rivals to investigate the possibility of growing those crops in other locales, free of Dutch hegemony. And that seedling of an idea would eventually give rise to one of the greatest acts of commercial espionage in the history of capitalism.

—

There is some debate among historians over whether the French missionary, botanist, and master smuggler Pierre Poivre (literally “Peter Pepper”) was in fact the original Peter Piper who, legend has it, picked a peck of pickled peppers. Certainly his name suggests a direct link (piper is Latin for “pepper”), and while pickled peppers do not appear in his biography, he did manage to pickpocket other valuable spices from the epicenter of the Dutch monopoly. Born in 1719, Poivre led a globe-trotting, multidisciplinary life. He served as a missionary in the Far East; sailed with the French East India Company; wrote a travel memoir and botanical survey that influenced Thomas Jefferson; and served as administrator of the French islands Isle de France and Bourbon, now known as Mauritius and Réunion.

At the age of twenty-six, Poivre was struck by a musket shot in the middle of a naval skirmish with the British; gangrene necessitated that most of his right arm be amputated, and he spent months recovering in the Dutch colony of Batavia, now Jakarta. His convalescence gave him plenty of time to observe the Dutch spice monopoly up close. His horticultural expertise—and his nationalist desire to help the French economy—put the idea in his head that with the proper care, clove and nutmeg plants could be cultivated in other parts of the world with climates similar to that of the East Indies. On his return trip to France, he spent time on the Isle de France and on Bourbon, and found both islands resembled the tropical rain forests of the Bandas and the Malukus. He would later write, “I then realized that the possession of spice which is the basis of Dutch power in the Indies was grounded on the ignorance and cowardice of the other trading nations of Europe. One had only to know this and be daring enough to share with them this never-failing source of wealth which they possess in one corner of the globe.” He began sketching out a plan to “liberate” the seeds of clove and nutmeg from Dutch control, a plan that would make him almost certainly the most successful one-armed bandit in history.

Poivre’s plan was both daring and extremely dangerous. The Dutch had grown out of some of their more bloodthirsty practices by this point, but their spice monopoly had been worth billions to their economy in modern dollars. They were not likely to hand over the seeds behind that empire to a Frenchman without a struggle. Poivre set sail across the Indian Ocean in 1750, arriving in the spring of 1751 in Manila, where he almost immediately encountered smugglers who sold him a supply of nutmeg seeds fresh enough that he could plant them. Thirty-two plants successfully sprouted, an early triumph that would keep him motivated through the many fruitless years that were to follow. But the nutmeg plants were only half the prize. Because clove spices are flower buds, not seeds, Poivre needed some way to get to an actual clove tree if he was going to introduce both spices to French soil.

Pierre Poivre

At this point, Poivre began an almost comical split-screen existence: frantically trying to secure passage to the Malukus to steal the billion-dollar asset from under the noses of the Dutch, and at the same time lovingly maintaining his personal spice garden of nutmeg plants, which slowly began dying off. (One theory holds that the seeds had been poisoned by an operative of the Dutch East India Company, the horticultural version of the KGB putting plutonium in a rival spy’s drinking water.) Poivre first tried to persuade the Spanish to take him to the Spice Islands, but they turned him down, not wanting to alienate the Dutch. Eventually he hired two boats and a Malay captain to take him to the Malukus, but naval battles in the southern islands delayed them so long that they ran up against monsoon season and had to turn back. By the time Poivre finally gave up on the cloves, in February of 1753, his nutmeg supply had dwindled down to nineteen plants. Stopping over on Pondicherry before rounding the horn of India, he reported only twelve still living. Somehow, five of the nutmeg sprouts survived the last thousand-mile journey back to safe harbor on Mauritius.

Once there, Poivre had to decide the best strategy for safeguarding his botanical treasure. “I knew from experience the incapacity of the gardeners of the Company at Mauritius,” he later wrote, “and the little care they had given to the plants of all varieties which I had brought from the Cape and from Cochinchina. Most of the plants had either been dug up by neighbors or had died from neglect.” Instead he quietly bequeathed the nutmeg plants to several friends on the island, planting them in three private gardens for extra protection. Before long, he was back in the East Indies, this time on a ship called the Colombe that managed to make it all the way to the Spice Islands. But this trip, too, proved to be ill-fated. He had difficulty anchoring off several of the islands; at one point, the ship’s surgeon snuck off in a dinghy to warn the Dutch, though he was apprehended before he could do any harm. Poivre’s attempts to woo the plantation workers and other non-Dutch residents were rebuffed. After months, he abandoned the scheme, and sailed west empty-handed.

Poivre’s mission might have died there and left him an obscure footnote in the history of spice, had he not decided to write his memoirs, which he eventually published as Voyages d’un Philosophe. Thomas Jefferson read the book and hatched a scheme to bring rice farming to the American south based on Poivre’s description of Chinese rice farms. A French minister back in Paris also read the memoirs with great interest. Inspired by Poivre’s vision of bringing valuable spices—and profits—to the island colonies of the French empire, the minister arranged a position for Poivre as administrator of Isle de France and Bourbon, and secured official support for the plot to grow Dutch spices in French soil. In 1770, Poivre dispatched two ships to the Spice Islands, led by captains with long experience in the region. They returned with thousands of healthy nutmeg sprouts and three hundred clove seedlings. The first cloves to grow anywhere outside a hundred-mile radius of Indonesia were harvested in 1776 on Isle de France. It seems preposterous to say it, but one of the key events that brought an end to the Dutch financial empire of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was a one-armed Frenchman stealing a handful of seeds halfway around the globe.

Poivre’s triumph, in a way, marked the beginning of the end for the spice trade, or at least the spice trade in its grandiose phase. Before long, descendants of Poivre’s initial batch of clove seedlings would be employed to launch a thriving clove business in Madagascar and Zanzibar. “Nearly two hundred years later,” Turner observes, “the flow of spices across the Indian Ocean has been reversed, with Indonesia now a net importer of cloves.” The newfound geographic diversity of cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, and pepper—and the increasingly efficient means of harvesting them—soon demoted spices from luxury item to commodity.

—

Interestingly, one of the last spices to descend the ladder into commodity status originated not in the Far East but in the Americas. On the gulf coast of Mexico, in a region now known as Veracruz, a vine with distinctive pale yellow flowers grows in the tropical forests. The vine is, technically, a member of the orchid family, but it is unique among the more than twenty-five thousand varieties of orchids in that it produces a crop: the vanilla bean. After pollination, the ovaries of the plant expand into long, thin fruits containing a multitude of black seeds. Thousands of years ago, the Totonac people of the Veracruz region discovered a technique for drying and curing these fruits that released a tantalizing aroma, a scent that would eventually suffuse ice cream parlors and birthday parties around the world.

“Perhaps the earliest known use for vanilla pods was as a simple but effective deodorant for the Indian’s houses,” historian Tim Ecott writes, “and it is still used in that way in central Mexico today, where a bunch of dried beans is tied together and suspended with string from a hook on a wall. Traditionally, the Totonac women, and women from other tribes in whose territory the plants grew, would place oiled vanilla beans in their hair, perfuming it with the subtle scent from the plant.” By the time Europeans arrived in the Americas, vanilla had become an important, if luxurious, part of the Aztec culture. The elite ground up the pods and used them to take the edge off the bitter taste of the chocolate drinks they made from the cacao plant. Regions that produced vanilla often paid their taxes to the Aztec state in vanilla pods.

Vanilla orchids and colocynth

Today, vanilla has come to be imagined as the yin to chocolate’s yang, an opposition heightened by the entirely arbitrary light coloring of vanilla ice cream and cake, but the truth is vanilla crept its way into the European palate as a kind of chocolate enhancer. A 1685 treatise entitled The Manner of Making Coffee, Tea, and Chocolate noted of hot chocolate drinks, “Everyone uses this confection, and puts therein Three little Straws or as the Spaniards call them Vanillas de Campeche. Our Vanillas are used in making the Chocolate, the which are very pleasant to the sight, they have the smell of Fennel, and perhaps not much different in quality, for all hold that they do not heat too much, and do not hinder the adding of Annis seed.” Eventually vanilla broke free of its codependence on chocolate. Thomas Jefferson developed a taste for the spice during his years in Paris, and returned to the states with a handwritten recipe for vanilla ice cream, one of his many enduring contributions to American culture. In 1791, Jefferson sent a note to the American emissary in Paris asking for special assistance in locating vanilla beans to be shipped back stateside, along with cases of fine Bordeaux wines: “[My butler] informs me that he has been all over town in quest of Vanilla, & it is unknown here. I must pray you to send me a packet of 50 pods (batons) which may come very well in the middle of a packet of newspapers. It costs about 24 sous a baton when sold by the single baton.” Vanilla never incited the mass obsession that erupted around pepper or psychoactive compounds like coffee, tea, and chocolate. But it was flavorful enough—and, crucially, scarce enough—that, by the middle of the 1700s, pods of vanilla were worth their weight in silver.

That scarcity resulted from a strange twist of evolution. The orchid species that produces the vast majority of vanilla consumed in the world—Vanilla planifolia—can only be fertilized, in nature, by one species of bee native to Mexico and parts of Central America; the reproductive organs of the plant are so carefully guarded that other bees and insects that haven’t coevolved with the flower will almost never accidentally fertilize it just by bumbling around in search of nectar and swiping some pollen in the process. In a sense, Vanilla planifolia evolved a kind of combination lock in the design of its petals that only one specific insect can get past. For centuries, the complexity of that system confounded humans as well. After Cortés and his men brought back word of vanilla to Europe, cuttings of Vanilla planifolia were successfully planted in tropical locations (and even Northern European hothouses) all over the world. Like most orchids, the vine was lovely to look at, but without the Mexican bees, the plant stubbornly refused to bear fruit. The Dutch may have guarded their clove and nutmeg monopoly with warships and genocide, but the Mexican monopoly on vanilla was guarded by the petals of a flower.

The story of how the lock that protected the treasure of Vanilla planifolia was eventually picked may be the ultimate example of the way the spice trade bound the planet together in a network of unlikely affiliations. The story begins where we left off with Pierre Poivre—on the French islands of Isle de France and Bourbon. Poivre’s dream of replicating the lucrative crops of the Bandas on Isle de France and Bourbon hadn’t entirely come to pass in the years that followed his daring thieveries in the East Indies. (The clove plantings, for instance, never really took off until they made it to Madagascar.) But Bourbon proved to be a useful harbor for the French sailing back from India and the East Indies, in part because the island had been entirely uninhabited when Europeans first arrived on its shores. Over time, more than a thousand species of plants from around the world were cultivated on the islands; slaves were brought in from Africa to work coastal plantations where coffee, sugar, and cotton generated handsome profits for the French empire. The names of the islands changed as the political regimes shifted back in Paris: after the House of Bourbon collapsed, Bourbon was christened Isle de la Réunion; it spent a decade or so as Isle Bonaparte before reverting back to Bourbon during the Restoration. Only after the 1848 revolution did it finally settle on its modern name: Réunion.

Vanilla plants had been introduced to Réunion several times before that last name change; a bundle of cuttings that arrived from Paris in 1822 were dispersed through a number of plantations. The vines grew for as long as two decades, and would flower occasionally. But, deprived of the deft touch of the Mexican bees, the plants would almost never produce fruit. All that would change, though, thanks to the ingenious horticultural explorations of a twelve-year-old boy: Edmond Albius, a slave who worked on a plantation known as Bellevue. Albius had hit upon a method of fertilizing the plant, a delicate maneuver that involved opening up the lip of the flower with his thumb and using a stick to press two parts of the flowers’ reproductive organs together. As his master and surrogate father Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont would later recall, “This clever boy had realized that the vanilla flower also had male and female elements, and worked out for himself how to join them together.” Albius’s technique—“le geste d’Edmond,” as it came to be called—soon spread across the island. Before long, the plantations of Réunion were shipping cured vanilla pods by the ton. Within a half century of Albius’s discovery, the small island produced more vanilla than all of Mexico.

While the French prospered mightily from le geste d’Edmond, Edmond himself did not fare as well. Liberated in 1848, he was arrested and imprisoned for jewel robbery several years later, though his sentence was commuted as an acknowledgment of his contributions to Réunion’s economy, after intense lobbying from Bellier-Beaumont. He died in poverty on the island in 1880. The local paper recorded his demise with little sugarcoating: “The very man who at great profit to this colony, discovered how to pollinate vanilla flowers, has died in the public hospital at Sainte-Suzanne. It was a destitute and miserable end.”

Edmond’s is the story of spice in a nutshell, a story where plants and peoples from all across the globe are tossed together—sometimes in great triumph and sometimes in great tragedy—all to take the rarest of tastes and turn them into commodities. A plant indigenous to Mexico and controlled by the Spanish is planted on an island in the Indian Ocean by the French, where it is first fertilized by a boy whose African ancestors had been brought to the island by French slave traders. And that seemingly trivial act—a boy tricking a flower into producing seed, in the hills of a remote island—would somehow shift billions of dollars of economic activity from one part of the world to another, and turn a spice that was once pursued by only the elites of society into a flavor so ubiquitous that its name has become a synonym for the commonplace and the ordinary.

—

Every grade school history textbook will tell you that the spice trade played a pivotal role in world history. But it is worth pausing for a moment to contemplate how many key developments and customs—many of which persist to this day—have spices at their origin: international trade, imperialism, the seafaring discoveries of Columbus and da Gama, the fall of Rome, joint-stock corporations, the enduring beauty of Venice and Amsterdam, global Islam, even the multicultural flavor of Doritos. Having a taste for spice is not just one of the luxuries that the modern world affords us; having a taste for spice is, in part, why we have a modern world in the first place. The most perplexing thing about that legacy is not the fact that spices were once fabulously expensive and are now cheap. (The pattern of luxury goods becoming mass commodities is in some sense the macro-narrative of capitalism: from cinnamon to cotton to computers.) The real question is why human beings were willing to pay so much money for such frivolous tastes.

The closest equivalent in modern times to the global impact of spices is our current appetite for oil. Just like the quest for spices, the quest for oil has compelled humans to redraw political borders, launch devastating wars, make brilliant scientific and technological breakthroughs, and create some of the most profitable companies in history. But at least fossil fuels, for all their faults, are actually necessary given the energy requirements of our lifestyles. You could easily imagine wars or empires or corporations being launched in the name of basic nutrition; food is life, after all. But conquering the world in the name of flavor? Where is the sense in that?

The conventional explanation for the spice craze attributes it indirectly to the need for basic nutrition. In Roman or medieval times, the story goes, the available food required massive amounts of spice to make it edible. Pepper and its ilk were considered a supplement to salt: a way of preserving food through the depths of winter, and of disguising the flavor of meat that had begun to spoil. This theory has been widely discredited for relatively straightforward reasons. The fantastic expense of spices like pepper or nutmeg meant that they were almost exclusively used by the European elite until the price began to fall in the 1600s. In medieval England, the extended royal family single-handedly dominated the market for spices. (Edward I, for instance, spent as much on spices annually as an earl would earn in a typical year.) The European aristocracy had no shortage of fresh meat or fish to consume, and they had plenty of salt to preserve anything that needed a longer shelf life. Spice was a craving, not a necessity. “To limit their function to food preservation and explain their use solely in those terms,” the German historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch writes, “would be like calling champagne a good thirst quencher.”

Were spices just a financial bubble, like Dutch tulips and Pets.com stock? Almost certainly not. To begin with, if spices were merely a bubble, it was the longest in the history of markets; it took almost two thousand years to burst. More importantly, the market price of spices like pepper and cinnamon was rarely influenced by second-order speculation: people driving up the price by betting that the price will go up. Those derivative markets wouldn’t flourish until after the heyday of spices, partly because of economic institutions, like publicly traded companies, that spices helped invent. Spices were expensive because wealthy people were willing to pay significant sums to consume them, not just bet on their future value.

Why, then, were the medieval aristocrats so obsessed with spices? Consider an occupation that was once common in wealthy households, now lost to history: the speciarius, or spicer. According to Turner, Philip V of France had only four officers in his chamber: a tailor, a barber, a taster, and a spicer; the English king Edward IV had an entire “Office of Greate Spycerye.” Tailors and barbers are still recognizable functions, and a taster makes intuitive sense given the threat of poisoning. But why carve out an entire office for the spicers? The word itself conjures up an image of some officious valet, standing at attention all day with a pepper grinder in his hands. But the medieval spicer provided much more than flavoring. For starters, managing an inventory of spices was itself a complex and challenging job, given their value and the scale of the royal feasts that featured them so prominently. But the spicer also played a crucial role that makes no sense in the modern context: he was somewhere between a pharmacist and a lifestyle coach. He was there to advise the royal family on the daily rhythms of their health and well-being: everything from chronic illnesses to sleeping patterns to bowel movements. And spices were the primary means of altering or preserving those rhythms.

Engraving of African medicinal plants, 17th century

Over its long history as a health supplement, pepper was considered a remedy for everything from cancer to toothache to heart disease. The Spanish king Philip II sent his personal physician to Mexico in 1570 to analyze the pharmacological potential of local plants. His description of the medical properties of vanilla alone suggests just how powerful these new compounds were considered to be: “a decoction of vanilla beans steeped in water causes the urine to flow admirably; when mixed with mecaxuchitl, vanilla beans cause abortion; they warm and strengthen the stomach; diminish flatulence; cook the humours and attenuate them; give strength and vigour to the mind; heal female troubles; and are said to be good against cold poisons and the bites of venomous animals.”

Sexual dysfunction, too, was reliably treated with spice-based remedies. In De Coitu, the sex manual composed by the eleventh-century Benedictine monk Constantine the African, almost twenty recipes for sexual enhancement are listed; all of them rely on spices for their aphrodisiac powers. To the modern ear, the descriptions sound more like the ingredients for a delicious salad dressing than some medieval Viagra. Constantine describes an “electuary that I made for impotent men of cold and moist complexion: 6 drams ginger, camomile, anise, caraway; 4 drams hellebore seed, onion seed, colewort seed, ameos; 2 drams long pepper, black pepper, nut oil, as much honey as needed.” As late as 1762, a German physician published a study in which he claimed, “No fewer than 342 impotent men, by drinking vanilla decoctions, have changed into astonishing lovers of at least as many women.” Perhaps inspired by these accounts, the Marquis de Sade served copious amounts of vanilla with his desserts, to inflame the passions of his dinner guests.

Spices were not just considered to have medicinal attributes, in the soft, New Age way that we talk about the “healing properties” of aromatherapy today. In an age without Tylenol or antibiotics or Claritin, spices were medicine, running the gamut from what we would now call dietary supplements all the way to treatments for cancer or dementia. Much of this pseudoscience played off the then-dominant paradigm of bodily humors. Inherited from the Greeks, this framework conceived of health as a matter of balancing the four humors and their defining attributes: blood (warm and moist); bile (warm and dry); phlegm (cold and moist); and black bile (cold and dry). Unlike some folk medicines, the humoral system appears to have exactly zero correlation with any actual bodily mechanisms now known to science, but that didn’t stop it from dominating the practice of medicine for almost two thousand years. The unhealthy body was a body in which one or more of the humors had a disproportionate influence, and that bodily harmony (or lack thereof) was heavily shaped by what you ate: pork and fish, considered cold and moist, would make you more phlegmatic; vegetables were considered dry, and thus exacerbated a bilious condition. Spices, then, were employed to keep the humors in equilibrium. Since many of them were considered hot and dry, they were often employed to combat the excesses of moist or cold dishes, especially meat, pork, and fish.

Actual medicines, delivered separately from meals, could take on astonishing complexity. These “compounds,” as they were sometimes called, were prescribed by spicers to combat everything from gas pains to insomnia to depression. The most famous of these was theriac. Allegedly first concocted by the Persian king Mithridates VI as an antidote to reptilian venom, theriac was the ultimate panacea, used to treat—or ward off—just about any ailment possible. Some recipes included as many as a hundred separate ingredients. Measured purely by the complexity of its component parts, modern Doritos have nothing on theriac. A Dutch apothecary’s guide from the late 1600s included both black and long pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, and clove, along with more than fifty other ingredients—lesser calamint, white or common horehound, West Indian lemongrass, wall germander, Cupressaceae, bay laurel, and so on.

On the one hand, you can see in the staggering multiplicity of the theriac recipe the antecedent of modern miracle drugs, whereby billions of dollars and thousands of individuals converge to create a complex molecular cocktail designed to preserve our health. On the other, it seems bizarre to have such a meticulous prescription with so little actual medical value. And this helps us understand one underlying cause behind the strange prominence of the medieval spice: pepper, clove, nutmeg, and cinnamon became intensely valuable because the channels of innovation do not always run at the same speed. We invented a whole host of institutions and conventions that would ultimately turn out to be extremely useful in improving our health: diets and cookbooks shaped by a complex understanding of bodily systems, chemical compounds designed to treat illness and prescribed using standardized systems of measurement, printing presses and pharmacists that could disseminate those prescriptions. These were all significant innovations, not easily established. But as it happened, they arrived before the invention of the scientific method, randomized double-blind control drug trials, and other regulatory mechanisms that separated the genuine healers from the charlatans. On some basic level, the medical properties of the spices were pure fantasy. But that fantasy, for all its absurdities, established a regimen of health and improvement that has carried on into modern life with better success. The spicers were a kind of trial run for the modern pharmacist and drug company, offering imaginary cures. We figured out the form for maintaining a healthy lifestyle before we invented a method for scientifically testing the content. In Middlemarch, George Eliot described this process, evoking the history of alchemy and its delusions, but it could just as easily be applied to the sham medicine of the spicers: “Doubtless a vigorous error vigorously pursued has kept the embryos of truth a-breathing: the quest of gold being at the same time a questioning of substances, the body of chemistry is prepared for its soul, and Lavoisier is born.”

Mostly these folk remedies were harmless, medically speaking; given the placebo effect, they might well have had a slightly beneficial impact. But, at least once, the use of spices as medicine seems to have backfired in a truly catastrophic way. The aromas of Oriental spice were said to combat the miasmatic air that conveyed plague. An Oxford fellow named John of Eschenden recommended “a powder of cinnamon, aloes, myrrh, saffron, mace, and cloves” to ward off the Black Death. A century later, an Italian endorsed Eschenden’s prescription, calling it a “marvellous medicine against the corruption to the air in the time of pestilence.” The carrier for the bubonic plague was the black rat, with the memorable Latin name Rattus rattus, whose fleas ultimately transmitted the disease to humans. Rattus rattus is not native to Europe; the species originated in Southeast Asia and almost certainly spread to Europe via the channels of the spice trade during the late Roman Empire. By medieval times, the rodent had proliferated across Europe, thriving in its dense and polluted city centers. In January of 1348, according to the Flemish writer De Smet:

Three galleys put in at Genoa, driven by a fierce wind from the East, horribly infected and laden with a variety of spices and other valuable goods. When the inhabitants of Genoa learnt this, and saw how suddenly and irremediably they infected other people, they were driven forth from that port by burning arrows and divers engines of war; for no man dared touch them; nor was any man able to trade with them, for if he did he would be sure to die forthwith. Thus, they were scattered from port to port.

Within a matter of months, the continent was under siege from the plague bacillus. Europeans, as it turned out, had it exactly wrong about spices. They weren’t protection against the Black Death. They were the reason the Black Death came to Europe in the first place.

—

The folk medicines peddled by the spicers should not lead us to a purely utilitarian explanation for the spice trade, however illusory its cures may have been. Another, more subtle appeal shaped the European craving for spices. To eat nutmeg or cinnamon or pepper two thousand years ago was, in a real sense, the most tangible way to experience the mystical realms that lay beyond the edges of the map, what Europeans would eventually call the Orient. Remember that, during the height of the Roman obsession with pepper, accurate maps of India didn’t exist, and the cloves that arrived from the Spice Islands were traveling from a part of the world that no Roman had visited. The first true globe-trotters were not human beings; they were the seeds and berries and bark of plants that were passed along the global relay system, from the Far East to the banquets of Rome. No wonder there was something magical about experiencing these flavors: you couldn’t see the Orient in photographs or television images; you couldn’t even point to it on a map. But you could taste it.

The Eastern allure was particularly powerful because a rich literature had developed suggesting that these distant parts of the world were, literally, an earthly paradise, either the actual location of the Garden of Eden or some close approximation. These origins help explain why spices were considered to have such significant medical powers; you were consuming something that had originated outside the fallen, debauched state of civilized man. To savor the clove or the nutmeg was to retreat back to a prelapsarian state, to eat as Adam or Eve had before their fateful encounter with the apple tree and the serpent.

However beautiful the Spice Islands may be, most of us would now consider them to be paradise with a lowercase p and not an actual Garden of Eden. But the vast distance those spices traveled does raise an interesting question. Almost all of the spices that eventually dominated the world’s cuisine originated far from Europe, mostly in Southeast Asia: pepper in India; clove, nutmeg, and cinnamon near Indonesia. Columbus was famously wrong about cinnamon and pepper in the Americas, but South America did ultimately contribute the chili pepper and vanilla to the global spice cabinet. If we are trying to explain how the world system of international trade came about—with both the cosmopolitan intermingling of cultures that we rightfully celebrate, and the horrors of slavery and imperialism that we rightfully denounce—then one of the central questions we have to ask is this: Why did Europeans have to travel so far to find spices? Imagine an alternate scenario in which pepper grows naturally in Spain, and cinnamon abounds in France, and clove trees dot the foothills of the Italian Alps. The course of human history would likely be completely redirected: Europe remains far more insular; Columbus and da Gama never bother to set off in search of a direct route to the East. Without the immense markup of a global spice network, the accumulated wealth of Venice and Amsterdam and London dissipates, along with all the pioneering works of art and architecture that wealth funded. Without a vibrant pepper trade with India, calico fabrics never make it to the drawing rooms and garment stores of London; without a booming market for cotton textiles, the industrial revolution is delayed for decades.

The extent to which the spice trade had bound the globe together was perceived sharply by many of the participants—even those who never boarded a vessel and set sail for the Far East. After commissioning the East India Company in 1600, Elizabeth I wrote a handwritten letter to the “Great and Mighty King of Aceh,” who controlled much of the pepper markets that had prospered around Sumatra (now Indonesia) in the 1500s. The missive was delivered in person by a British naval hero named James Lancaster, who led a small fleet of East India Company ships that arrived in Aceh in 1602. Elizabeth’s language is remarkable in its supplication; she talks a great deal about the “love” between her nation and Sumatra, no doubt trying to distinguish the British from those rapacious Dutch and Portuguese. But perhaps the most extraordinary passage comes when she attempts to integrate the global reach of the spice trade into a broader story of Divine Purpose: God, she explained, saw fit to distribute the “good things of his creation . . . into the most remote places of the universal world . . . he having so ordained that the one land may have need of the other; and thereby, not only breed intercourse and exchange of their merchandise and fruits, which do so superabound in some countries and want in others, but also engender love and friendship between all men, a thing naturally divine.”

Knowing the grim history that was to follow—almost four hundred years of colonial exploitation and slavery in pursuit of those “good things”—it is hard not to be cynical, if not outright appalled, by the talk of “love and friendship between all men.” But Elizabeth does hit upon an essential fact: that spices were distributed into the “most remote places of the universal world.” The taste for those spices compelled human beings to invent new forms of cartography and navigation, new ships, new corporate structures, not to mention new forms of exploitation—all in the service of shrinking the globe so that pepper raised in Sumatra might more efficiently be delivered to the kitchens of London or Amsterdam. The automata of Merlin’s Mechanical Museum demonstrated how the pursuit of leisure and play can be, on a conceptual level, exploratory, driving the creation of new social customs, materials, technologies, markets. But the pursuit of spice was literally exploratory: those strange new flavors propelled human beings around the globe like nothing that had ever come before them. Today’s global village has its roots in the frivolity of spice.

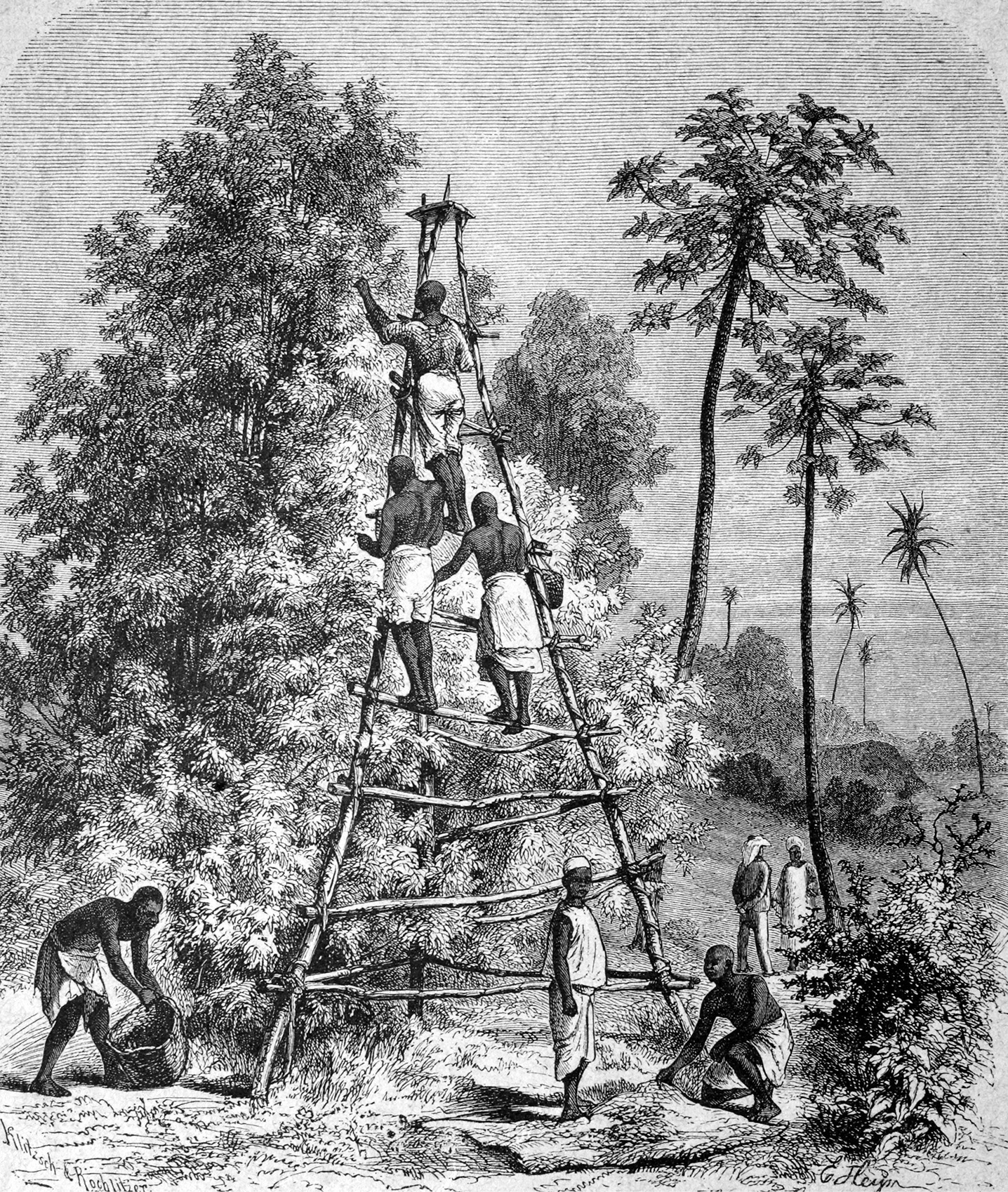

Clove harvesting

This still doesn’t answer the question of why Europeans had to travel so far, assuming we aren’t satisfied with Elizabeth’s providential explanation. Why weren’t the Spanish hills teeming with pepper vines? Here the ecosystems approach to human history, most famously presented in Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel, offers the most enlightening explanation. Diamond argued that civilization first took root in Mediterranean climates because those climates featured short rainy seasons and long dry seasons, which encouraged the cultivation of large-seeded grains like wheat and barley that became central to modern agriculture. Large, dense human settlements have become eminently possible outside of Mediterranean climates; indeed, some of the largest cities in the world are now located in Southeast Asia and South America. But it is very difficult to invent a large, dense settlement for the first time in, say, a tropical rain forest. And so the first societies that clustered into proto-cities, and left behind the subsistence lifestyles of the hunter-gatherers, were almost all located outside the tropics, in places rich with large-grained cereals.

Yet the challenges tropical climates pose for inventing civilization turn out to be opportunities when it comes to biological invention. There are more interesting flavors in the tropics because there is, on some basic level, more of everything in the tropics; that’s why anyone who values biodiversity is so distraught by the destruction of the rain forests. Tropical plants evolve such a wide array of chemical compounds in their fruits and berries and seedlings because they are interacting with a much wider array of parasites and predators and coevolutionary partners than their equivalents in the Mediterranean climates of Spain or Italy. Most of those chemical innovations turn out to be useless to humans, but some small portion turn out to have value, as medicines, materials, intoxicants, or just interesting flavors.

In his complaint about the Roman dependence on imported spices, the historian Pliny observed, “It is remarkable that [pepper’s] use has come into such favor: for with some foods it is their sweetness that is appealing, others have an inviting appearance, but neither the berry nor the fruit of pepper has anything to recommend it. The sole pleasing quality is its pungency—and for the sake of this we go to India!” We now understand the biochemistry of that pungent taste. Black pepper contains a molecule called piperine that activates a set of receptors on the surface of our tongues known as the transient receptor potential channels. These “TRP” receptors evolved to detect potentially harmful substances making contact with the skin; they function as a kind of alarm system for the body. When you accidentally grab a searingly hot pan, TRP receptors convert a chemical reaction happening at the epidermal layer into an electrical nerve signal that creates, in the mind, a sharp sensation of pain in your fingers. Both piperine and the active ingredient in the chili pepper, capsaicin, activate the TRP channels. This is why, on a biochemical level, it is not just a metaphor to say that spicy foods are “hot,” even if they are served at room temperature. The piperine or capsaicin creates a kind of illusion of heat, triggering the same bodily alarm that rings when you step on a hot coal by mistake.

Piperine and capsaicin almost certainly evolved in response to the biodiversity of their tropical homeland; from the plant’s point of view, in a world teeming with organisms that might potentially consume your seeds, it makes sense to arm those seeds with a substance that makes another organism feel as though its mouth were on fire. (Fruits evolved a different strategy, creating seeds that could survive digestion, and ensuring a wide distribution by wrapping those seeds in a delicious sugary flesh.) The pungency of pepper that Pliny decried originally served as a kind of chemical weapon, threatening to burn any creature that dared to eat the plant’s berries. The story of pepper is thus a kind of inverted version of Diamond’s account in Guns, Germs, and Steel: civilization took root in Mediterranean climates because large-seeded grains of wheat and barley were nearby and easy to consume; the global market of the spice trade arose because pepper grew only in distant tropical climates whose biodiversity had made it advantageous for the pepper berries to be painful to consume.

The bioweapon strategy did not just evolve among the plants. In 2006, a team of researchers announced that they had, for the first time, demonstrated that venom from a tarantula native to the West Indies activated the same TRP receptor that piperine and capsaicin trigger. At some point in the distant past, the ancestors of that tarantula hit upon a survival strategy that involved simulating intense, painful heat with their venom. Today, the Frito-Lay corporation sells billions of dollars’ worth of snack foods that rely on the exact same biochemical channels to create the perception of heat. When you taste that Doritos chip, you are receiving a signal that evolution has been crafting for millions of years, a signal with a simple, universal message: “Fire!”

And here’s the amazing thing: we took that signal and turned it into something enjoyable and unthreatening, something we eat for fun. Our genes want us to be wary of compounds that activate the TRP receptors, but we are not slaves to our genes. Sometimes the patterns and conventions of human culture flow naturally out of our evolutionary heritage, as with marriage rituals, spoken languages, and incest taboos. But often the true yardstick of cultural innovation comes in measuring how far the habits and customs and appetites of culture have taken us from our genes. Like many forms of delight, the taste for spice propelled us far from our roots—not just geographically but also existentially. That strange new taste on the tongue that would send any child into howls of pain could be savored by an adult, its pain turned into pleasure. Spices enlarged the map of possible desires, which in turn enlarged the map of the world itself. This boundary pushing, this constant reimagining of what our needs and appetites should be, may not be a “thing most divine,” as Queen Elizabeth had it. But it is what makes us different from most organisms. What makes humans human is, in part, their ability to expand the boundaries of what it means to be human. The exploratory need for new experiences, new desires, and new tastes is, more often than not, the force behind that expansion. You might even call it the spice of life.