6

Public Space

The Pleasuring Grounds

John Hughson was a down-on-his-luck cobbler when he decided, in the mid-1730s, to make a pilgrimage from Yonkers to Manhattan. He set up shop in the big city, then sporting a population of around twenty thousand people. Hughson opened a series of taverns, first by the banks of the East River, and then on the Hudson, near the site where the World Trade Center would rise, and fall, almost three centuries later. The tavern on the West Side soon developed a reputation as a popular watering hole—not just for the booze, but also for a regular “great feast” Hughson would host each Sunday. A crowd would start gathering after church services wound down, and Hughson would set out a table of mutton and goose, accompanied by rum, cider, and beer. “Someone might play a fiddle, and often there was dancing,” one historian writes. “There was gambling, too. Dice were rolled for prizes of bowls of punch, or wagers were laid on cockfights.” The great feasts were a time to “frolick and merry make,” a regular at Hughson’s later recalled. Some of that “merrymaking” involved prostitution as well; Hughson’s establishment was renowned for one prostitute in particular, a woman named Margaret Sorubiero, who seems to have gone by a string of aliases, but was most commonly known as “the Newfoundland Irish Beauty.”

In all, Hughson’s tavern was like many public houses or drinking establishments across colonial America or Europe at the time: a raucous, festive enclave with somewhat lax moral standards. But a visitor to Hughson’s would notice one key difference within seconds of walking into the tavern: while Hughson himself was white, his clientele was largely made up of African-American slaves mingling with a few lower-class whites, some of them soldiers. (The historians Edward G. Burrows and Mike Wallace suggest that the crowd also included some “young gentlemen inclined to after-hours carousing and gaming.”) While slavery wasn’t officially abolished in New York until 1827, taverns catering to slaves were not unheard-of in the city. A joint called Cato’s Road House, founded by a former South Carolina slave, stayed in business for fifty years during the first half of the eighteenth century, supplying brandy and cigars to slaves on the run from their southern masters. But the mix of white and black customers set Hughson’s establishment apart. Perhaps most scandalously, “the Newfoundland Irish Beauty” had openly had a child with a slave known as Caesar. The casual intermingling of races was otherwise nonexistent in eighteenth-century Manhattan; despite the city’s reputation for tolerance, the lines of racial segregation were clearly drawn. But at Hughson’s, those lines began to blur, with ultimately catastrophic consequences.

Starting in March of 1741, a series of suspicious fires erupted in Manhattan, beginning with a blaze at the governor’s house in Fort George, followed by fires at warehouses, private homes, and stables across the city. Word began to spread through the white population that the fires were being started by rebellious slaves; when an African-American slave named Cuffee was seen running from a blaze in early April, he was quickly arrested and thrown in jail. Vigilante crowds soon began hunting down other slaves and handing them over to the authorities. As the panic spread, a grand jury, supervised by a justice named Daniel Horsmanden, was convened to crack down on the white proprietors who were allegedly inciting revolt by supplying alcohol to African-Americans, which naturally brought the authorities to John Hughson.

As it turned out, Hughson was already in trouble with the law. Alongside the gambling and the prostitution, he apparently ran a profitable side business fencing stolen property out of his tavern. (The tavern, for all we know, may have actually been the side business, with the fencing the main moneymaker.) The local police had long suspected that Hughson was part of a larger crime organization, but hadn’t been able to find convincing evidence of his wrongdoing, until a sixteen-year-old indentured servant of Hughson’s named Mary Burton decided to inform on her boss after the authorities offered to free her from her obligations to him. Initially, Burton merely accused Hughson of conspiring with Caesar in a recent robbery of a general store on Broad Street. But after the fires broke out, Burton took her role of accommodating witness to a whole new level, becoming, as the historian Christine Sismondo puts it, “more than happy to give up the name of everybody involved in the robbery, the fencing, and, it would turn out, just about anyone whose name she’d ever even heard.” Burton reported that she had overhead numerous conversations during which Hughson, Caesar, and Cuffee actively discussed inciting a slave rebellion by leaving the city in ashes. Hughson allegedly told Caesar that in the new regime, the two men would be “King” and “Governor” respectively. (Many historians today believe the two men were discussing leadership of a crime syndicate, not a post-rebellion slave colony.) Burton also testified that she had overhead slaves at Hughson’s tavern exclaiming, “God damn all the white people.”

Burton’s testimony triggered one of the most brutal eruptions of state violence in the history of New York. Horsmanden’s grand jury swiftly convicted Caesar of burglary, and on May 11, he and another slave were hanged in gallows near Freshwater Pond. The authorities left his body hanging from the scaffolding for weeks as a savage reminder of the fate that awaited other rebellious slaves. Within a matter of weeks, Cuffee and another alleged conspirator were sentenced to death by fire. They attempted to buy themselves a more lenient sentence by giving away the names of other supposed conspirators (many of whom were eventually hanged), but their last-minute confession did them no good. They were burned alive in front of an enraged mob.

The grand jury then turned to Hughson, who, along with his wife and the Newfoundland Irish Beauty, were quickly sentenced to hang as well. The trial made it clear that Hughson’s true offense lay in the social space he had created in the tavern itself, with its scandalous mingling of black and white and its reversal of traditional race relations. During the proceedings, one justice asserted that Hughson had broken the law simply by selling “a penny dram of a penny worth of rum to a slave, without the direct concept or direction of his master.” During the sentencing, another judge made the case against Hughson’s integrationist tendencies in the strongest language imaginable:

For people who have been brought up and always lived in a Christian country, and also called themselves Christians, to be guilty not only of making Negro slaves their equals, but even their superiors, by waiting upon, keeping with, and entertaining them with meat, drink and lodging, and what much more amazing, to plot, conspire, consult, abet and encourage these black seed of Cain, to burn this city, and to kill and destroy us all. Good God! When I reflect on the disorders, confusion, desolation and havoc, which the effect of your most wicked, most detestable and diabolical councils might have produced, (had not the hand of our great and good God interposed) it shocks me!

In the end, after executing the two women alongside Hughson, the authorities strung up Hughson’s body next to the decomposing corpse of Caesar. A bizarre rumor spread through the city that, in death, Caesar’s skin had turned white, while Hughson’s had turned black, a macabre end to a story that had, from the beginning, revolved around the scandalous interactions of white and black skin.

The turbulent events of that spring are generally referred to today as the “Slave Rebellion of 1741” or the “New York Conspiracy of 1741.” But the truth is no one knows for certain whether there was a rebellion or a conspiracy at all. The most plausible scenario is that Hughson’s accomplices may have been setting fires as a distraction while they stole goods from nearby stores and homes. But it’s also possible that there was no connection between Hughson and the fires, and the whole thing was the creation of a sixteen-year-old girl’s imagination, enticed into her accusations by the promise of freedom. But one fact in this entire murky business remains unchallenged: Hughson’s tavern was guilty—in the eyes of the New York establishment—of expanding the boundaries of legitimate social interaction between the races. Whatever illegal activities were perpetrated in Hughson’s tavern, the community that formed in that environment was, in a real sense, a century or two ahead of its time. Today, in most parts of the United States, we wouldn’t think twice about a bar that attracted a multiracial clientele. But in 1741 it was apostasy. The most telling clues about the future of racial integration were not visible in the homes or churches or businesses of New York. If you wanted to see where race relations were headed, you had to go to a bar.

—

The tavern is an ancient institution, almost as old as civilization itself. We have no record of the cunning entrepreneur who first came up with the idea of carving out a space where drinks could be purchased, and camaraderie enjoyed, with a group of friends and strangers. Most likely the idea was independently developed by many people at different places and times. (Once you had beer, beer gardens inevitably beckoned.) When they first emerged, the taverns marked the origin point of a line that would lead not just to McSorley’s, and Harry’s Bar, and Cheers. The birth of the drinking house also marked the origins of a new kind of space: a structure designed explicitly for the casual pleasures of leisure time. The tavern was not a space of work, or worship; it was not a home. It existed somewhere else on the grid of social possibility, a place you went just for the fun of it. Our modern world is now teeming with these spaces: bars, cafés, spas, resorts, casinos, theme parks. Entire cities now brand themselves as entertainment experiences, escapes from the daily grind. The original taverns, wherever they took root, gave humans the first glimpse of that wonderland future, with all its glamour and its absurdity.

Roman tabernae ruin in Pompeii

The birth of the tavern deserves a place in the history books as a symptom of rising standards of living. “Luxury goods” predate the first cities, in gems and other trinkets that passed through Neolithic society. But luxury experiences were something new. Creating an economic system where it was possible to drop down to the local bar and spend some spare cash on drinks for a few hours—this was no small achievement in itself. For the most part, we tolerate bars and pubs and taverns as guilty pleasures: yes, they attract (and encourage) illicit behavior, as Hughson’s fencing ring and the Newfoundland Irish Beauty attest. But the sentimental, communal appeal of the local dive usually overrides that puritanical scolding. What we rarely acknowledge, however, is the transformative role taverns and bars have played in our political history. Your seventh-grade history book may have told you that democracy was born in the agora, where toga-wearing philosophers debated the issues of the day in the town square. But the truth is democracy, like countless scandalous offspring since, was just as likely to have been conceived in a bar.

The word tavern derives from the Roman tabernae, although the ancient Greeks had public drinking houses as well, where heavily watered-down wine was served to patrons. Archeologists cataloging the ruins of Pompeii discovered 118 distinct taverns in the town; the ash cloud from Vesuvius even preserved a chalkboard with a wine list inscribed on it: “For one [coin] you can drink wine; For two you can drink the best; For four you can drink Falernian.” On one tavern wall, two-thousand-year-old graffiti complains about the quality of the booze: “Curses on you, Landlord, you sell water and drink unmixed wine yourself.”

Since many tabernae also doubled as inns, Romans also deployed taverns as nodes on their vast imperial network, layover points that enabled men to travel thousands of miles with a reliable form of shelter—and a good drink—guaranteed almost every night. According to W. C. Firebaugh, one of the earliest historians of Greco-Roman tavern culture, “the stages of travel were so admirably calculated that the end of each day’s journey found the traveller at a station where fresh horses and pack animals could be obtained, and where food and lodging were procurable.” It wasn’t enough to build a global network of roads, all leading to Rome; the Romans had to create a system whereby travelers could make it to the ends of the empire and back without relying on the kindness of local strangers, or sleeping in a field or forest. Roman planners built taverns every fifteen miles on the road, becoming a de facto unit of measuring distance. The tavern system was a key resource in managing the logistical nightmare of maintaining a global empire in an age before trains, planes, automobiles, or the Internet.

But however important the Roman tabernae may have been to the empire itself, their ultimate legacy lay in introducing the convention of public drinking houses to much of Europe. In England, those Roman taverns evolved into that most iconic of British institutions: the “publican” or “public house”—or as we now say, the pub. The census of 1577 reported the existence of more than sixteen thousand pubs in England, which suggested a ratio of one pub for every 187 residents. (Today, the ratio in the UK is closer to one pub per thousand citizens.) Not surprisingly, that level of pub density triggered much outcry from the more sober members of society. “The multiplying of taverns is evident cause of the disorder of the vulgar people,” Secretary of State William Cecil warned, “who by haunting thereto waste their small substance which they weekly get by their hard labor and commit all evils that accompany drunkenness.” But the pubs were not just inciting disorderly conduct; they also established a home for a new kind of conversation and community, what the historian Ian Gately calls “a fresh ethos”:

[Pubs] were run by the people, for the people. They were places where men and women from different occupations and backgrounds might meet to drink and to enjoy each other’s company, and where they might talk with candor about their rulers. Indeed, the common people enjoyed a freedom of speech and action in their drinking places that was denied to them elsewhere, and these institutions became the nucleus of a popular culture.

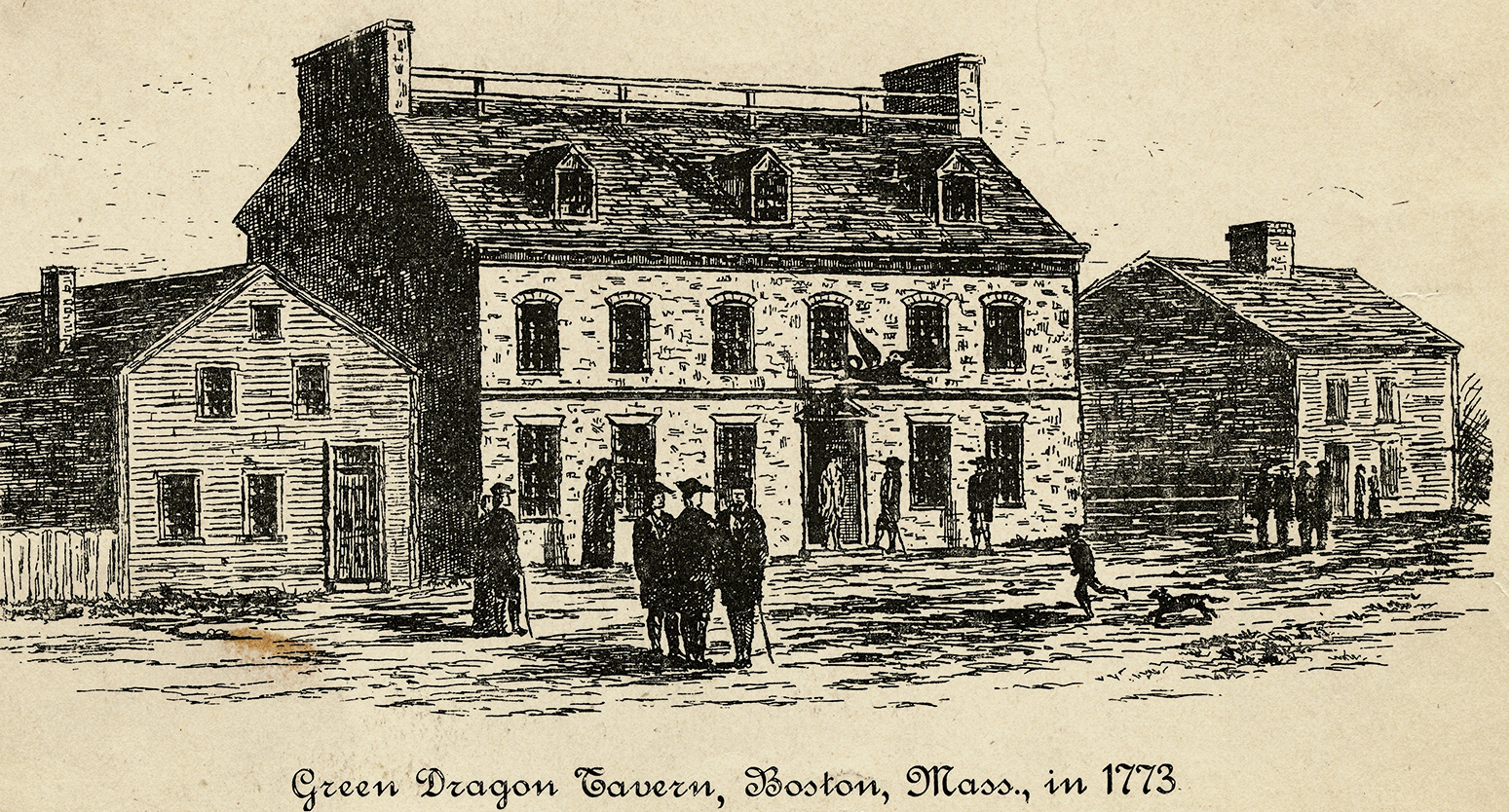

The political impact of the drinking house would be felt most profoundly not in England but in her colonies. Ben Franklin once estimated that there was a tavern for every twenty-five men in Philadelphia—far exceeding the pub density of Britain. Just as Hughson’s tavern played a defining role in the alleged slave rebellion of 1741, taverns throughout the American colonies were the seedbeds of the rebellion that would ultimately become the Revolutionary War. The legendary Boston Caucus that would eventually spawn the Boston Town Meeting and the Sons of Liberty first formed in a Boston tavern run by Elisha Cooke Jr. (The word caucus itself either derives from “Cook’s House” or the Greek word for wine bowl.) The plans for the Boston Tea Party were hatched in another Boston tavern, the Green Dragon, which came to be known as “the headquarters of the American Revolution.” A decisive independent streak ran through the tavern culture of the colonies; many taverns, like Hughson’s, were used by smugglers trying to evade British taxes. (An underground tunnel connected the kitchen of a Philadelphia tavern to the city docks.) An analysis of voting records from the 1700s by historian David Conroy has shown that tavern keepers made up a disproportionate number of representatives elected to the Massachusetts House, causing John Adams to complain that the coarse and raucous taverns were “becoming in many places the nurseries of our legislators.” Both Thomas Paine’s Common Sense and the Declaration of Independence were read aloud in taverns throughout the colonies, stoking the fires of revolution.

It is difficult, in fact, to find a single momentous event in the decades leading up to the Revolutionary War that didn’t unfold, in part, in the semipublic confines of a tavern. Erase those drinking establishments from history and it is entirely possible the radical front of the Sons of Liberty would have taken far longer to self-organize, and the revolution itself could have been postponed for decades. A revolutionary war with a fully industrialized Britain in the early 1800s might well have gone the other way.

It’s worth pausing for a second to get the causality right here. American independence wasn’t caused by the prevalence of tavern culture in the colonies. There were many forces at work, some of them likely stronger than the space of dissent that the tavern offered the early revolutionaries. But the existence of that space was nonetheless a determinate factor in the way the events unfolded. Change that one variable, and the buildup to the War of Independence has to, at the very least, unfold along a different path, since so much of the debate and communication relied on the semipublic exchange of the tavern: a space where seditious thoughts could be shared, but also kept secret. Like the Roman tabernae that preceded them, the American taverns were critical nodes on a network. The Romans used them to keep one empire together. The Americans used them to topple another.

—

The scene spilling out of the Black Cat Tavern in Los Angeles’s Silver Lake neighborhood on the night of December 31, 1966, was precisely the sort of spirited chaos you might expect to find at an urban gay bar on New Year’s Eve. A costume party had just ended at another bar down the street, and a trio of African-American men in drag—known as the Rhythm Queens—had launched into a upbeat rendition of “Auld Lang Syne.” Gay bars like the Black Cat had become increasingly visible in American downtowns in the postwar years, though their roots extended back to nineteenth-century establishments, like Pfaff’s Beer Cellar in Manhattan, the Bohemian enclave where Whitman sought out the “beautiful young men . . . with bright eyes.” The bars were both pickup spots and a rare space where gay and lesbian people could be open about their sexual identity in an age when the closet was the only option. Like Pfaff’s, they also served as networking hubs for the creative class: Tennessee Williams spent many hours at Café Lafitte in Exile in New Orleans; Allen Ginsberg held court in San Francisco’s Black Cat.

But these bars were also spaces of challenge and confrontation. Mingling in the crowd that New Year’s Eve night in Los Angeles were a dozen plainclothes officers from the LAPD Vice Squad, long the enemy of the city’s gay population. As the balloons dropped, marking midnight, and the men in the Black Cat embraced and exchanged New Year’s kisses, the undercover officers—assisted by a sudden influx of uniformed police bearing billy clubs—attacked and arrested sixteen men, beating several so badly that they had to be hospitalized. The undercover officers later testified that they had seen six men “kissing other men on the lips for up to ten seconds.” All six were subsequently found guilty of “lewd conduct.”

The Green Dragon tavern, Boston

The raid at the Black Cat preceded the much more famous confrontation at the Stonewall Inn in the West Village of Manhattan two years later. But the events of that New Year’s Eve night played a critical role in the formation of the gay rights movement. Six weeks after the raid, a street protest was staged on Sunset Boulevard, with hundreds of gay Angelenos chanting, “No more abuse of our rights and dignity.” Inspired by the Black Cat affair, a group of activists that had recently formed an organization called Personal Rights in Defense and Education (PRIDE) decided to turn their biweekly mimeographed newsletter into a genuine newspaper. The result was the Advocate, the first national publication devoted exclusively to the gay and lesbian community—a publication that would eventually become an essential component of the many struggles and victories of the gay community of the ensuing decades: the post-Stonewall birth of gay liberation, the HIV/AIDS crisis, and the gay marriage movement.

You can think of the impact of the semipublic space of bars and clubs on the politics of gay liberation as a kind of cultural hummingbird effect. Many of the unlikely transformations we have surveyed here revolved around technological breakthroughs: someone invents a device specifically designed for a single purpose, but the introduction of that device into wider society triggers a series of changes that the inventor never dreamed of. A group of showmen and amateur scientists stumbles across a technique for fooling the eye into perceiving motion in a series of still images, and a century and a half later, that innovation has created a new class of celebrity, and a cottage industry devoted to nourishing the imaginary relationships between reality-show stars and their fans. But some of the most influential innovations in our history do not involve new machines or scientific principles. Bars and pubs and taverns might have used new technologies over the centuries—from corkscrews to kegs to refrigerators—but what made the drinking house so transformative had nothing to do with the contraptions it employed. The innovation, instead, was more social and physical: the idea of a space that was both open to the public but also closed off from the street, where one could comfortably alter one’s mental state for a few hours. Over the long arc of history, this innovation would prove to be as important as the more traditional breakthroughs in the canon of good ideas: the sextant, say, or the pocket watch. The immediate purpose of the tavern was clear: it was an environment that made it easy for people to get drunk, and for the proprietors to make money by selling the drinks. But the hummingbird effect of the tavern turned out to be social and political: the tavern proved to be an environment that pushed the boundaries of social relationships, encouraging experimentation and nurturing dissent. The first person to hang out a shingle and serve drinks to paying customers—at some point back in the dawn of civilization—almost certainly had no idea that his or her innovation would ultimately support political and sexual revolutions that would reverberate around the world. A space originally intended for play and leisure became, improbably enough, a hotbed of dangerous new ideas.

These kinds of spaces played a defining role in one of the most influential works of sociology published in the twentieth century: Jürgen Habermas’s The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Originally conceived while Habermas was working as a graduate student under the legendary Frankfurt School Marxists Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, the book was actually his doctoral dissertation, though Habermas broke off with his mentors due to their “paralyzing political skepticism.” (With almost fifteen thousand citations tracked in Google Scholar, it stands as one of the most cited dissertations in the history of academia.) Habermas observed that, starting around the middle of the seventeenth century, the concept of “the public” (or le public in French, or Publikum in German) took on a new prominence in the languages of Western Europe. Before this point, people alluded to “the world” or “mankind” when talking about a general audience or crowd. But the idea of a public implied that there was a body of opinion and taste that possessed its own force and influence in society, potentially rivaling that of the monarchies and clergy. For the first time, people began talking explicitly about the court of “public opinion”; they began to seek “publicity” for their work or ideas, a word that originates with the French publicité. Habermas argued that the political and intellectual revolutions of the eighteenth century had been facilitated by the creation of this new public sphere, largely housed in semipublic gathering places like taverns and pubs. (A few decades after Habermas, the American sociologist Ray Oldenburg would develop a similar thesis in a book called The Great Good Place—coining the now-common expression “the third place” for these venues.) For Habermas, the public sphere had a profoundly egalitarian bias, creating “a kind of social intercourse that, far from presupposing equality of status, disregarded status altogether. [Participants] replaced the celebration of rank with a tact befitting equals.” And, like the Black Cat and the Stonewall Inn two centuries later, it was a space that “presupposed the problematization of areas that until then had not been questioned.” For Habermas, the public sphere was not simply architectural; it was also facilitated by new developments in media, particularly the rise of pamphleteering that was so central to Enlightenment discourse.

Taverns, salons, and drinking societies play a role in The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. (Had Habermas focused more on the American Revolution, they might have even had a starring role.) But for Habermas, the revolutionary ideas of the eighteenth century were ultimately dependent not on the beer and wine of tavern culture, but on another drug that had just arrived in the cities of Europe: coffee.

—

The story of how humans developed a taste for coffee—and, indirectly, an addiction to caffeine, now the most popular psychoactive compound on the planet—conventionally dates back to the Ethiopian city of Harar, where it is believed that the coffee plant, Coffea arabica, was first domesticated. But in a way, the story is much older than that. After all, the distant ancestors of Coffea arabica began producing caffeine in their berries long before humans noticed that the drug provided a pleasant jolt of mental stimulation. Modern genomics has now begun to explain why the plants evolved this potent chemical in the first place. In September of 2014, an international team of researchers, led by French and American scientists, announced that they had sequenced the genome of Coffea canephora, a plant that now accounts for about a third of the coffee consumed around the world. Analyzing sections of the genome that direct the production of caffeine, and comparing them to equivalent caffeine-producing machinery of the plants that produce tea and chocolate, the researchers discovered that Coffea canephora evolved a unique set of enzymes dedicated to the creation of caffeine compounds. In other words, the staple crops that deliver caffeine into the human bloodstream appear to have independently developed caffeine production, instead of descending from one common ancestor.

That convergent evolution may be partially explained by caffeine’s use as a kind of chemical weapon, not unlike the pungent, burning taste of piperine. The coffee plant sheds leaves laced with caffeine, which make the surrounding soil inhospitable to other plants that might compete for resources or sunlight, and the high doses of caffeine in the berries themselves poison insects that might be otherwise inclined to eat the berries. But as the science writer Carl Zimmer has observed, the evolution of caffeine may not have been entirely defensive, noting that the coffee plant also includes low levels of caffeine in the nectar it produces. “When insects feed on caffeine-spiked nectar,” Zimmer writes, “they get a beneficial buzz: they become much more likely to remember the scent of the flower. This enhanced memory may make it more likely that the insect will revisit the flower and spread its pollen further.” In this one respect, our cultural exploitation of caffeine’s chemistry may have run parallel with its evolutionary function, given the drug’s well-studied capacity to enhance the memory centers of the brain.

From the beginning, coffee walked a fine line between medicine and recreational drug. Its utilitarian purposes—increasing short-term memory, combating drowsiness—have always been an undeniable part of the beverage’s appeal. Caffeine likely played some role in the great expansion of intellectual and industrial activity that Europe witnessed in the eighteenth century, at the exact moment that coffee and tea became staples of the European diet, particularly in England and France. (The Europeans effectively swapped out a depressant—the default daytime beverage of alcohol—for a stimulant en masse, with predictable results.) Certainly caffeine was a crucial ingredient in easing the workforce of the first industrial towns into the regimented schedules of factory time. But caffeine was more than just a smart pill; an entire complex of devices and techniques evolved around the Coffea arabica berry to make it more pleasurable to extract the caffeine from its naturally bitter state: grinders, milk steamers, French presses, espresso machines. Tea, by comparison, never attracted the diverse arsenal of devices that coffee did, perhaps because tea was less challenging to the palate in terms of flavor. When you read the accounts of the Europeans first encountering coffee in the sixteenth century, it’s hard to find a single person who enjoyed the beverage for its taste. (Those early caffeine adventurers would likely be baffled to read the descriptions on a coffee blog today.) One seventeenth-century drinker described the taste of coffee as a “syrup of soot and the essence of old shoes,” while the London Spy called it the “bitter Mohammedan gruel.”

Turning coffee into something that could be independently savored for the subtleties of its taste was a project that wouldn’t be successfully achieved until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the seventeenth century, what made coffee fun was as much about architecture and urbanism as it was about taste receptors. Coffee made Europeans more alert and improved their recollection, but the coffeehouse gave them a new compound, built by social connections instead of enzymes.

—

Sometime around 1650, a Sicilian manservant named Pasqua Rosée found himself briefly in the employ of a British merchant named Daniel Edwards in Smyrna, then part of the Ottoman Empire. Edwards had developed a taste for coffee in his travels through modern-day Turkey, and so on his return to London he brought Rosée back with him as a kind of in-house barista. Serving coffee to Edward’s cronies, Rosée sensed that this still-exotic Turkish drink presented a business opportunity, and he began investigating the possibility of selling coffee in a public venue modeled after the coffee shops of Istanbul and other Levantine cities. The history at this juncture is a bit blurry: Rosée may have either gone into business with Edwards or fallen out with his employer and partnered with one of his friends. What is uncontested is that Rosée began selling coffee from a shed in a churchyard near Edwards’s house in 1652, promoting it with a sign painted with an image of his own head, prompting its patrons to dub it “The Turk’s Head.” It was London’s first coffeehouse: the origin point of an institution that would be more influential than any other public space in England over the next century and a half.

Rosée published a leaflet on the “Vertue of the COFFEE Drink,” which is worth quoting at length, both for the curious pleasure of hearing someone describe an everyday object to an audience that has never experienced it, and to chuckle over how far Rosée went in evangelizing the drink’s medicinal powers.

The Grain of Berry called Coffee, groweth upon little Trees, only in the Deserts of Arabia . . . It is a simple innocent thing, composed into a Drink, by being dryed in an Oven, and ground to Poweder, and boiled up with Spring water, and about half a pint of it to be drunk . . . It is very good to help digestion, and therefore of great use to be [consumed] about 3 or 4 o’clock afternoon, as well as in morning. [It] quickens the Spirits, and makes the Heart Lightsome . . . It suppresseth Fumes exceedingly, and there good against the Head-ach, and will very much stop any Defluxion of Rheums, that distil from the Head upon the Stock, and to prevent and help Consumption and the Cough of the Lungs. It is excellent to prevent and cure the Dropsy, Gout, and Scurvy . . . It very good to prevent Mis-carryings in Child-bearing Women.

There’s something undeniably charming about Rosée’s salesmanship here; not content with the entirely accurate pitch that the “Coffee Drink” would help with digestion and headaches and provide mental stimulation, he somehow found it necessary to throw in tuberculosis, scurvy, and miscarriages as well. One can only imagine the amount of money Starbucks would make today had caffeine actually possessed all of these medicinal attributes. Anticipating the caffeinated industrial revolution that would arrive in the next century, Rosée also noted that his drink would “prevent drowsiness and make one fit for business.”

Interior of a London coffeehouse in the 17th or 18th century

Rosée’s leaflet did the job, and he soon found himself selling six hundred cups—or “dishes,” as they were called—in a single day. Before long, coffeehouses sprouted all across London. Within a decade, there were eighty-three coffeehouses in the city, all of them catering to men. (As Habermas notes, one of the notable differences between the London coffeehouse and its Parisian equivalent, the salon, was that women were active participants in the latter.) Excluded from the “man’s world” of coffee and chatter, a group of London women published in 1674 a Woman’s Petition Against Coffee, which thundered against the “Excessive use of that Newfangled, Abominable, Heathenish Liquor called COFFEE.” (The “Calico Madam” critique that emerged thirty years later can be seen as a kind of return volley.) A year after the Woman’s Petition’s publication, Charles II joined forces in attacking the coffeehouses, fearing that they were encouraging idle behavior and seditious political movements. His “Proclamation for the Suppression of Coffee Houses” described the threat in decisive terms:

Where it is most apparent that the multitude of coffee houses of late years . . . and the great resort of idle and disaffected persons to them have produced very evil and dangerous effects, as well for that many tradesmen and others do herein mis-spend much of their time which might and probably would be employed in and about their lawful calling and affairs, but also for that in such houses, divers false, malitious, and scandalous reports are devised and spread abroad to the defamation of His Majestie’s Government . . . His Majesty hath thought it fit and necessary that the said coffee houses be (for the future) put down and suppressed . . .

You can hear beneath that formal syntax the guttural cry of moral panic that would echo for centuries every time new leisure spaces emerged to scandalize older generations: from the department stores of the nineteenth century, to the pool halls of the early twentieth, to the video-game arcades of the 1980s. Charles might have “thought it fit and necessary” to suppress the coffeehouses, but the citizens of London thought otherwise. After a violent outcry from both the proprietors and customers of the new establishments, Charles withdrew his proclamation only a week after proclaiming it. However useless it was as a legal intervention, the language of the proclamation made it clear that the real challenge to authority that the coffeehouse presented had little to do with the drug itself and everything to do with the social space that the coffeehouse introduced to English society. By the early 1700s, London neighborhoods featured more than a thousand coffeehouses, far more than any city in the world. (Amsterdam, at that point the only city in Europe to rival London’s affluence, only had thirty-two as of 1700.) More than any other physical environment, the coffeehouse would nurture and inspire the commercial, artistic, and literary flowering of the British Enlightenment.

Satirical print of a “Coffee House Mob,” 1710

In part that cultural transformation was enabled by the remarkable specialization that characterized the coffeehouse ecosystem in the 1700s. Coffeehouses clustered in Exchange Alley specialized in stock-market speculation; Waghorn’s in Westminster was a hotbed of political gossip. Others functioned as gambling dens or brothels; some catered to more obscure interests, as in John Hogarth’s coffeehouse, where the conversation was exclusively conducted in Latin. The historian Matthew Green writes, “At the Bedford Coffeehouse in Covent Garden hung a ‘theatrical thermometer’ with temperatures ranging from ‘excellent’ to ‘execrable,’ registering the company’s verdicts on the latest plays and performances, tormenting playwrights and actors on a weekly basis.” Perhaps most famously, coffeehouses served as the de facto offices for a newly forming journalistic class. In the inaugural issue of the Tatler in 1709, Richard Steele explained how his news and commentary would be sourced from the specialized chattering classes of London’s coffeehouses:

All accounts of gallantry, pleasure and entertainment shall be under the article of White’s coffee house; poetry under that of Will’s coffee house; learning under the title of Grecian; foreign and domestic news you will have from St. James’ coffee house, and what else I shall on any other subject offer shall be dated from my own apartment.

In some coffeehouses, the threads of our history of play converged. Lloyd’s Coffeehouse catered to the maritime community, ultimately evolving into the insurance giant Lloyd’s of London. Born in a coffeehouse, the modern insurance business used the mathematics of probability invented by dice players to make it financially viable to send ships around the world in search of fashionable new fabrics like calico and chintz.

—

But the cultural impact of the coffeehouses did not exclusively rely on their catering to specific niches. Many, like the London Coffeehouse, where Ben Franklin and Joseph Priestley held court in the 1760s, were intensely multidisciplinary in their interests, lacking the specialized focus of a corporate headquarters or a university department. They were spaces where intellectual networks converged. “Unexpectedly wide-ranging discussions,” Green writes, “could be twined from a single conversational thread as when, at John’s coffeehouse in 1715, news about the execution of a rebel Jacobite Lord (as recorded by Dudley Ryder) transmogrified into a discourse on ‘the ease of death by beheading’ with one participant telling of an experiment he’d conducted slicing a viper in two and watching in amazement as both ends slithered off in different directions. Was this, as some of the company conjectured, proof of the existence of two consciousnesses?”

In some influential coffeehouses that eclecticism was visible in the decor itself. In the early 1700s, a London doctor named Hans Sloane began collecting exotic items that would eventually fill nine rooms of a manor house in Chelsea. An observer in 1730 described a small subsection of Sloane’s collection:

. . . A Swedish owl, 2 Crain Birds, a dog; vast No. Of Agats, an Owel in one, exact, orange; Tobacco in others, Lusus Naturae; an opal here; Catalogue of Books, about 40 volumes; 250 large Folios, Horti Sicci; Butterflies in Nos.; 23,000 Medals; Inscriptions, one exceeding fair from Caerleon; A fetus cut out of a Woman’s belly, thought she had the dropsy; lived afterwards, and had several Children.

By the time of his death, Sloane had assembled more than seventy thousand objects, which he bequeathed to King George II. Sloane’s collection was a particularly accomplished version of what the Germans called Wunderkammerns—literally, “cabinet of wonders.” Wunderkammerns were small shrines to the gods of miscellany, featuring ancient coins, trinkets, embalmed mummies, daggers, rhinoceros horns, and the like. No organizing principle united these objects; to find a home in the cabinet of wonders, objects needed only the capacity to surprise the aristocrats who were invited to survey them. But Sloane’s collection was not only perused by the London elite. An enterprising barber and dentist named James Salter struck a deal with Sloane in the first years of the 1700s, borrowing a few items from Sloane’s growing collection. Salter put them on display in a new coffeehouse he had opened near Chelsea Church; before long, Salter had adopted the more exotic name Don Saltero, and his cabinet of wonders and caffeine became a popular destination for London’s cognoscenti, its walls and ceilings covered with hundreds of oddities: barnacles, wampum, a “flaming sword” that allegedly belonged to William the Conquerer, petrified oysters, a tooth extracted from the mouth of a giant, whips, backscratchers, and gems.

Archduke Albert and Archduchess Isabella Visiting a Collector’s Cabinet, circa 1621–23 by Jan Breughel the Elder and Hieronymus Francken II

Many of Sloane’s wonders originated in ancient history, but the collection they formed turned out to belong to the future. Shortly after Sloane’s death, his vast archive of exotica became the foundation of the British Museum, whose charter of incorporation declared that it provide “not only for the inspection and entertainment of the learned and the curious, but for the general use and benefit of the public.” It was the first national museum in history that truly belonged to the people, almost half a century before the French revolutionaries opened the doors of the Louvre.

Two very different traditions descend from Don Saltero and Sloane’s curations. One line leads to the carnival huckster showmanship of Ripley’s Believe It or Not: a collection of oddities of dubious origin, arranged to amuse tourists and gawkers. But the other line has a more advanced pedigree. The cabinet of wonders was the physical embodiment of a new kind of scholarship, a new model for the intellectually curious. To be a scholar in the centuries before Don Saltero was to be versed in the classics and the Bible; it implied focus and diligence and a deference to the ancient wisdoms. The intellectual imagination that flowered in the 1600s and 1700s was fundamentally different: it was multidisciplinary, global in its scope, intrigued by oddities as much as by classical knowledge. Diderot’s Encyclopédie and the Encyclopaedia Britannica both emerged from the ethos of the collector. In a famous passage from The Prelude, Wordsworth drew upon the Wunderkammern as a metaphor for his desultory intellectual pursuits at Cambridge as a young man:

I gazed, roving as through a cabinet

Or wide museum (thronged with fishes, gems,

Birds, crocodiles, shells) where little can be seen

Well understood, or naturally endeared,

Yet still does every step bring something forth

That quickens, pleases, stings . . .

Wordsworth was capturing a sensibility that was enjoyed, during his day, by a tiny slice of the population, but that would become far more mainstream in the years to come: the idea of college as a time of intellectual play, a time to experiment, to dabble in eclectic interests and attitudes. The idea lives on today as a legacy of Romantics like Wordsworth, but it can be traced back even further, to the curiosity shops and coffeehouses of the Enlightenment collector.

—

Like the temples of illusion and department stores that would follow them, coffeehouses were environments where social classes converged: poets, lords, stock speculators, actors, gossips, entrepreneurs, scientists—all found a seat in the shared environment of the coffeehouse. It was not, to be sure, an environment that welcomed women or the working poor. (Most establishments charged a penny for admission, easily affordable to the middle class, but just dear enough to discourage common laborers.) But by the standards of the eighteenth century, it was, almost certainly, the most egalitarian room that modern Europeans had ever experienced. As early as 1665, a pamphlet on the new coffeehouse culture observed, in verse: “It reason seems that liberty / Of speech and words should be allow’d / Where men of differing judgements croud, / And that’s a Coffee-house, for where / Should men discourse so free as there?” Roughly a decade later, a set of “Rules” prescribing coffeehouse etiquette instructed, also in verse:

First, Gentry, Tradesmen, all are welcome hither,

And may without Affront sit down Together:

Pre-eminence of Place none here should Mind,

But take the next fit Seat that he can find:

Nor need any, if Finer Persons come,

Rise up for to assign to them his Room.

In his 1712 travelogue, John Macky noted that in coffeehouses, one regularly witnessed “Blue and Green Ribbons and Stars”—decorative emblems marking the highest echelons of British society—“sitting familiarly, and talking with the same freedom, as if they had left their Quality and Degrees of Distance at Home.”

The inherent democracy of the coffeehouse was an achievement on its own, one that would play a role in political democratization over the course of the next century. But it also led to a staggering number of innovations: the first public museums, insurance corporations, formal stock exchanges, weekly magazines—all have roots in the generative soil of the coffeehouse. Countless other innovations in engineering, agriculture, and navigation were seeded by the “premiums”—or prizes—awarded by the Royal Society of Arts, founded in Rawthmell’s Coffeehouse in Covent Garden in 1754. To its early critics, the coffeehouse may have looked like a space of indulgence and lethargy, a place where men went to escape what Charles II called “their lawful calling and affairs.” But that escape—as scandalous as it seemed initially—turned out to be enormously productive. Escaping your lawful calling—and your official rank and status in society—not only created a new kind of leisure, it also created new ideas, ideas that couldn’t emerge in the more stratified gathering places of commerce or religion or domestic life. Coffee may not have proved to be the miracle drug that Pasqua Rosée envisioned, at least in terms of the physical health of the people who drank it. But its cultural impact was nothing short of miraculous.

—

The century and a half that followed the first industrial breakthroughs of the 1750s is often imagined as a dark tide of factories rising across the planet, in England first, then through Northern Europe and America. But alongside that steam-powered march, a different kind of space proliferated as well, a kind of inverted image of the mechanized thunder and drudgery of the factory: spaces designed deliberately for the experience of leisure and entertainment. The coffeehouses in London, the taverns of Philadelphia, the grand department stores of Paris, the “ghost makers” in Berlin, the moving panoramas of New York—cities began to teem with new ways for people to escape “their lawful calling and affairs,” for a few hours at least. Leisure, for the first time, became not so much a commodity—since part of the pleasure came from the uniqueness of each new attraction—but rather a kind of environment for sale, crafted for maximum enjoyment value.

This was a profoundly urban phenomenon, but as the illusionists and department-store magnates steadily took over the downtowns of cities across the world, a parallel revolution took place far from of the metropolitan centers. Wilderness, too, was transformed from a space of fear and hardship into a space organized around, and celebrated for, the human pleasures it induced. The romance of immersing yourself in nature, “getting away from it all,” was not something that came naturally to humans, who had been walling themselves off from nature since the birth of agriculture. In 1620, when the first Pilgrims sailed into exquisite Cape Cod Bay, passing the dunes outside of Provincetown that would centuries later attract vacationers from around the world, they reported that they had found themselves in “a hideous and desolate wilderness full of wild beasts and wild men.” Scenes that today evoke grandeur and awe were in many cases abhorrent to a seventeenth-century eye, at least among the Europeans who were educated enough to record their impressions. Mountains in particular were thought to be aesthetically offensive. They were called “warts,” “boils,” and even in one bizarre case “nature’s pudenda.” As late as the eighteenth century, travelers through the Alps would often ask to be blindfolded to avoid looking at the awful scenery. When they looked at a mountain, they imagined it as a habitat they might have to survive in, rather than as a postcard image of Natural Beauty. While human beings seem to have an innate fondness for natural greenery—what E. O. Wilson famously called biophilia—that deep-rooted instinct appears to have been overpowered by ten thousand years of agricultural and urban settlements. Wilderness back then was something to conquer, not contemplate.

Horace-Bénédict de Saussure

The word innovation is conventionally used to describe advances in science or technology; the lightbulb is an innovation, as is the iPod. But our lives today have been shaped not only by new gadgets but also by new ideas and attitudes that had to be nurtured and disseminated by people who were in many cases as visionary and as driven as Thomas Edison or Steve Jobs. The idea of nature as a space to seek out and savor aesthetically was one of those attitudes. It seems intuitive to us today, living in a world where national parks attract tens of millions of visitors a year. But that sensibility was itself a kind of cultural innovation, one that that came together in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

If the very idea of the “great outdoors” was an innovation, then the question becomes: Who were the innovators behind it? The conventional story points to the poets and painters—to Wordsworth and Keats and Turner—who began explicitly thinking of nature as the phenomenon most likely to trigger that mix of awe, pleasure, and fear that the Romantics called “the sublime.” But our modern sense of nature as a space to be enjoyed as a recreational act also dates back to an eighteenth-century scientist named Horace-Bénédict de Saussure. Born in Geneva in 1740, de Saussure was a member of the Swiss aristocracy, but he was also a man of science: a botanist, geologist, and a natural philosopher. De Saussure was particularly fascinated by those hideous monstrosities of the natural world—mountains—believing that they offered tantalizing clues about the geological composition of the earth and its atmosphere. But turning those clues into genuine understanding meant the mountains would have to be climbed.

One mountain in particular caught de Saussure’s attention: Mont Blanc, the highest peak in Western Europe, popularly known as “the Accursed Mountain.” De Saussure believed that if he could get to the top, he could collect valuable data about the earth and its atmosphere. But mountaineering was effectively unknown as a skill, precisely because summits like Mont Blanc offered nothing useful or valuable to the humans gazing up at their peaks. Humans had navigated oceans, built canals, crossed deserts, but always because some reward (real or imagined) lay at the end of the journey. Climbing fifteen thousand feet of ice, snow, and rock with nothing to reward you but a sense of achievement made no sense—particularly when the mountains were rumored to be the habitat of monstrous creatures. As late as 1723 a Swiss fellow of the Royal Society published a detailed description of the dragons that lived in the Alps.

De Saussure recognized that he didn’t have the skills and fortitude to discover a route to the top of Mont Blanc on his own, and so he offered a reward to the first climber to make the ascent. On August 8, 1786, the French climbers Jacques Balmat and Michel Paccard reached the summit for the first time, and claimed de Saussure’s reward shortly thereafter. With the route now mapped, de Saussure set out to become one of the first to follow in the footsteps of Balmat and Paccard. As a well-bred aristocrat, he made the historic ascent in style, with a team of eighteen servants and guides, and a kit that included an entire bed, along with “mattresses, sheets, coverlet and a green curtain,” a tent, a ladder, a parasol, two frock coats, two nightshirts, two cravats, and a pair of slippers.

The cravats and coverlets may seem a little rich to the modern climber, used to the extreme efficiency of outdoor gear, but de Saussure was not just bringing the niceties to the summit of Mont Blanc. He also brought an extensive supply of scientific tools to capture as much data as possible from the peak. He used two large barometers to confirm the height of the summit; he measured the air temperature and the humidity and recorded the boiling point of water at altitude. He fired a pistol to record the effect of altitude on sound, and measured the pulses of his companions, taking detailed notes on their sense of smell and taste at high altitude. He recorded the stratigraphy of rock types and tracked which flowering plants and animal life were able to survive at such a high elevation—including two butterflies flying above the snowline. He even measured the precise color of the sky, using a custom color chart of his own design called a cyanometer. According to his analysis, the sky was the deepest blue he’d ever seen: “39 degrees blue.”

The science was groundbreaking on multiple levels. Perhaps most significantly, de Saussure’s analysis of mountain landscapes suggested to him that the earth was much older than had been conventionally assumed, evidence that would become a cornerstone of Darwin’s theory of evolution a century later. But de Saussure’s description of the view ended up being as influential as his barometric readings and geological surveys. He later published a book recounting his mountaineering adventures. “I could hardly believe my eyes; it appeared to me like a dream, when I saw placed under my feet those majestic summits,” he wrote of Mont Blanc. For some reason, the words resonated in the public imagination. Many followed in de Saussure’s footsteps to see the incredible sight for themselves, marking the birth of alpine tourism. A small industry in Mont Blanc memorabilia quickly sprouted; miniature scale models of the mountain were sold to tourists. De Saussure donated bits of granite he collected from the summit to prominent institutions for display and study. For a while, owning a fragment of Mont Blanc was like owning a piece of NASA-certified moon rock or a pebble from the Berlin Wall.

De Saussure’s explorations—and his travelogues—helped transform the general public’s relationship to nature. By the end of the century, the rhetoric describing mountain landscapes had been entirely reversed. No longer warts and boils, alpine summits became “palaces of nature” and a “terrestrial paradise.” But mountains were only part of the transformation. A rising middle class began looking at nature with new eyes: remote mountains, valleys, canyons, waterfalls, lakes, and rivers became marquee destinations. Most unusual ecosystems or geographical features were entirely unknown to the average citizen at the dawn of the eighteenth century, and even the educated classes would never think of setting off to visit a mountain or ocean-side cliff just for the aesthetics of the experience. But de Saussure and his followers changed all that. Nature tourism emerged as a leisure pastime. No longer a space to be feared, nature itself became a kind of wonderland, protected and mapped for the purposes of human delight. New gadgets arrived to enhance the tourist experience as it was happening, ironically by offering a degraded version of the spectacle they had traveled to see. Standing at the base of the Matterhorn or gazing out over the cliffs of Gibraltar, tourists captured the vista with an odd contraption called a “Claude glass,” named after the landscape painter Claude Lorrain. The device was effectively a tinted mirror, designed to re-create the aesthetics of an oil painting, not unlike the deliberately degraded filters of Instagram. Tourists turned their back on the mountain or the waterfall, held up the tinted mirror, and appreciated the vista in the reflection.

A Claude glass, 18th century

The shifting relationship to nature was reflected, and amplified, by changes in artistic expression. Dramatic landscapes shifted from the backgrounds to the foregrounds of paintings. In the United States, paintings and early photographs of the American west were deployed by the railroads to encourage migration westward. Some of this new obsession with nature was stoked by the illusionists, who brought thrilling virtual renditions of wilderness to metropolitan centers. In addition to John Banvard’s Grand Moving Painting of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, moving panoramas which also offered tours that allowed spectators to simulate a ride down the Nile or a journey across the epic landscapes of the American west to California and Oregon. Mountaineering, too, found a place in the palaces of illusion. In the 1850s, a British showman and mountain climber named Albert Smith created a moving panorama that documented his own alpine conquests. Smith built a simulated Swiss chalet inside London’s Egyptian Theater, where rapt audiences watched the panorama unfurl as Smith narrated his exploits. The show—titled Albert Smith’s Ascent of Mont Blanc—played more than two thousand times to sold-out crowds during the 1850s.

Inevitably, as more people fell in love with untouched wilderness, a growing chorus began to argue for preserving these spaces indefinitely. In April of 1872, an act of Congress declared a block of land in the territories of Wyoming and Montana “as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people,” the first national park in human history. Today, Yellowstone National Park attracts more than three million visitors a year, and 1,200 national parks of comparable scale have been established in more than a hundred countries around the world.

—

New cultural institutions often emerge at the intersection points of older strains, like a complex of streams that converges to form a single river. (Think of the way the cinema arose out of the nexus of the magic-lantern illusionists, early photographers, traditional theater, and the thaumatrope.) By the end of the nineteenth century, a new kind of wonderland became imaginable, one that took the cosmopolitan ethos that had been growing for the preceding two centuries and turned it into a weekend attraction. The wellsprings that fed this new form were multiple: the new interest in nature as spectacle; the runaway popularity of Great Exhibitions, like the Crystal Palace of 1851, that showcased objects of wonder from around the world; the new urban parks being designed in New York and Paris and Boston; and the roving circuses of Barnum and Bailey. Many of these environments derived from conventions that had first been developed behind the fences of royal estates and other aristocratic properties: follies, gardens—nature sculpted and arranged for the amusement of an idle stroll or a carriage ride.

The public zoos that first appeared in European and American cities in the middle of the nineteenth century embodied these many influences: the newfound interest in experiencing nature; the global vistas of an imperial age; the private menageries of royal courts now opened to the public. The London Zoo opened in Regents Park in 1828 as a purely scientific institution, but quickly began a practice of admitting well-to-do members of society who wished to enjoy its exotic collection of animals. By the 1840s, the zoo had opened its doors to the general public. Its benefactors believed that the pastime of viewing lions, elephants, and rhinos would function as what they called “rational recreation,” delighting the mind as well as the body and widening one’s appreciation for the natural bounty of life on earth—all in a few acres in the middle of a teeming metropolis. A guidebook to the zoo from the 1840s outlined what the average zoo visitor might expect:

In his mind’s eye he may track the pathless desert and sandy waste; he may climb amid the romantic solitudes, the towering peaks, the wilder crags of the Himalayan heights, and wander through the green vales of that lofty range whose lowest depths are higher than the summits of European mountains; or he may peer among the dark lagoons of the African rivers, enshrouded by forests whose rank green foliage excludes the rays of even a tropical sun; for here he has the evidence and the fruits of those countries which have hitherto been only to him an impalpable and uncertain idea.

The dream of global experience that had begun with the spice trade’s “taste of the Orient” had taken on a new material reality: you could now see (and no doubt smell) creatures from the four corners of the world without even leaving the city limits. The “impalpable and uncertain idea” of creatures from Africa or Asia was now, thrillingly, staring straight into your eyes.

One of those creatures was an orangutan named Jenny, who had been brought to the zoo in 1837 after the park’s original orangutan, Tommy, died of tuberculosis after only a few months in captivity two years earlier. Stories of manlike apes that lived in Africa had fascinated Europeans for centuries, and a handful of skeletons and specimens mounted by taxidermists had appeared in museums and Wunderkammerns; but until Jenny and Tommy’s arrival, none of the great apes had survived a sea voyage to England. The public’s interest in Jenny was naturally quite expansive, an interest that was stoked by the zoo’s insistence on dressing both Tommy and Jenny up in human clothes. Tommy sported a “Guernsey frock and a little sailor’s hat,” while Jenny was dressed like a proper British schoolgirl. The apes were taught to take tea, and Jenny eventually learned to follow many spoken commands from the zookeepers. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert witnessed one of the orangutans enjoying tea in 1842; she wrote in her diary that she was “too wonderful,” but also “frightful, and painfully and disagreeably human.”

The sight of an orangutan in fancy dress sipping a cup of Earl Grey may seem more Bedtime for Bonzo than something you might have expected from a serious zoological society, but Jenny’s fashion sense and manners played a critical role in the nineteenth century’s greatest scientific breakthrough. In the spring of 1838, Charles Darwin spent several rapt hours watching Jenny, “in great perfection.” During his stay, the keeper showed Jenny an apple, but then withheld it, and the two began a complex exchange that astounded Darwin. He later recalled:

She threw herself on her back, kicked and cried, precisely like a naughty child. She then looked very sulky and after two or three fits of passion, the keeper said ‘Jenny if you will stop bawling and be a good girl, I will give you the apple.’ She certainly understood every word of this, and though, like a child, she had great work to stop whining, she at last succeeded, and then got the apple, with which she jumped into an arm chair and began eating it, with the most contented countenance imaginable.

Several weeks after his visit to the zoo, but months before the famous “Malthusian epiphany” where he allegedly hit upon the theory of natural selection, Darwin wrote a passage in his journal that dared to suggest the evolutionary link that would so shock the world more than two decades later. “Let man visit Ourang-outang in domestication, hear its expressive whine; see its intelligence when spoken [to], as if it understood every word said; see its affection to those it knew; see its passion and rage, sulkiness and very actions of despair; let him look at the savage . . . and then let him dare to boast of his proud pre-eminence . . . Man in his arrogance thinks himself a great work, worthy the interposition of a deity. More humble and I believe true to consider him created from animals.” We think of natural selection as an idea that required a voyage across the world, far from London, to the Galápagos and beyond. But the most controversial element of Darwin’s idea arose in part because the world had come to London, in the “rational recreation” of the Regents Park Zoo.

The impact of the nineteenth-century zoo would not always be quite so erudite. In the years after Darwin’s visit with Jenny, the growing interest in nature as a kind of entertainment experience fed a blossoming of public zoos across Europe; in the 1860s, a new zoo opened on average every year in Germany. With the general public no longer satisfied by the stuffed animals on display in museum dioramas, a new class of wild-animal traders emerged, supplying zoos, circuses, pet shops, and menageries around the world with thousands of exotic animals. A cross between P. T. Barnum and Indiana Jones, a German animal trader named Carl Hagenbeck became a minor celebrity, with a reputation for daring adventures to the far corners of the earth, capturing dangerous beasts and bringing them back alive to the urban centers of Europe. (The character of Carl Denham in King Kong was cast from the mold that Hagenbeck first created.) Hagenbeck truly was an inveterate traveler, averaging more than thirty thousand miles in a year—the equivalent of ten flights across the Atlantic. In the age of trains and steamships, that was a staggering amount of time on the road. But Hagenbeck did almost none of the actual animal capture himself; instead, he ran a vertically integrated system that stretched from trappers in sub-Saharan Africa to the showrooms and expositions that Hagenbeck began establishing across Europe and the United States. Wild-animal trader has an undeniably buff ring to it as a job description, but in the end Hagenbeck’s success was largely due to his skills at supply chain management. Notoriously, the showman did not limit himself to the animals of the world; he also staged a number of hugely successful—and, to modern eyes, hugely offensive—exhibitions of “savages in their natural state”: Inuits from Labrador, Nubians from the Egyptian Sudan.

Yet, for all his travels, Hagenbeck’s most important legacy didn’t take shape until he settled down. In 1897, he bought a thirty-five-acre estate in Stellingen, outside Hamburg, and set out to build a new kind of park. “An enormous task lay before us: to transform a wasteland into a luxury park,” he later wrote, “a pleasure park with waterfalls and mountain formations, with practical animal shelters and buildings devoted to pure leisure.” His eventual creation, Tierpark Hagenbeck, is now considered one of the world’s first theme parks. Carnivals and traveling fairs had existed for centuries, of course; mechanical rides had entertained visitors at the 1893 Chicago Columbia Exposition; Hagenbeck himself had contributed a flagship attraction to Coney Island’s Luna Park when it opened in 1903. But no one before him had ever dared to build a permanent park as a kind of simulated world, a fully immersive experience that created the sense of global exploration and adventure without any of the actual risks that genuine exploration required.

Opening in 1907, Hagenbeck’s park would eventually stretch over eighty acres; anticipating Disney’s designs, he created fake mountain landscapes that concealed animal shelters, service entrances, heating pipes, and an electric motor that powered a waterfall. Across his artificial landscape Hagenbeck placed animals, native people, and villages: in a sense, an enormous moving panorama populated by live beings. A visitor entering the park would see a pond of aquatic birds with a field of deer beyond, stretching up to a ravine inhabited by lions, all backed by a mountain ridge beyond which ibex and wild sheep grazed. Paths, tunnels, and trails wound through the faux terrain with vistas at the peaks, where tourists could pretend to be de Saussure contemplating the view from the summit of Mont Blanc. Instead of bars or glass, Hagenbeck used the terrain to separate predators from prey, building deep but invisible trenches to keep the spectators and native people safe. (Thomas Edison visited the park and was apparently terrified when he walked around a group of trees and came face-to-face with a lion.) Some of the attractions combined immersive landscapes, zoological display, and rides. At the summit of the “Northern Plateau,” visitors could survey a frozen expanse of a simulated Arctic Sea populated by polar bears and seals, and then board a “Canadian tobogganing slide” that whisked them through a rocky crevasse, past the polar bears and a herd of caribou.

Tierpark Hagenbeck, one of the world’s first theme parks

The park was an immediate hit: more than ten thousand turned up to its opening day; by 1914, 7.5 million people had passed through its gates. “When you approach the Lions’ Ravine,” one visitor recalled, “surrounded and vaulted by majestic cliffs, you experience the feeling as though you were walking in the desert and happened upon a brook of lions, and, since you know that you are safe, you enjoy this sensation as purely aesthetic.” The mix of innovations that made that “pure aestheticism” possible had an undeniable commercial impact on the twentieth century. The theme-park industry today is one of the most lucrative entertainment businesses in the world. (In the United States alone, amusement parks generate more than $50 billion in economic activity each year.) But these fantasylands turned out to have philosophical implications as well. A rich tradition of continental philosophy emerged in the 1970s—most famously Umberto Eco’s Travels in Hyperreality and Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation—decrying the illusory artifice of modern culture, all the theme restaurants and megamalls and old downtowns converted into spectacles of consumption. “Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real,” Baudrillard famously announced in Simulacra and Simulation, “whereas all of Los Angeles and the America that surrounds it are no longer real, but belong to the hyperreal order and to the order of simulation.” Written by Europeans who represented an old-world philosophical tradition, albeit ones with an interest in pop cultural semiotics, Eco and Baudrillard’s travelogues contained a healthy measure of anti-American condescension, as though the escapism of Disney’s fantasy parks was a kind of ideological virus that the United States had unleashed on the world. But Carl Hagenbeck’s Trierpark is a useful corrective to that story: theme parks hit their mature phase in postwar America, but they spent most of their adolescence in Europe, among the ghost makers and illusionists and wild-animal traders.

Hagenback may have propelled us toward Eco’s hyperreal future with his simulated mountain ranges and fake savannas. But in the end, his creation may have turned out to be all too real. He died in 1914; legend has it that he was bitten by a venomous tree snake that he had brought back from Africa.

—

The modern world is now brimming with “pleasuring grounds,” in cities, suburbs, and rural parts of the globe. The market capitalization of Starbucks is currently $85 billion, making it one of the most valuable restaurant and food-service companies in the world. Where cities once nurtured the palaces of illusion and other entertainment venues, now the escapist fantasies nurture entire cities. Orlando, regularly the most visited city in the United States, is an urban center almost entirely created by the decision of Walt Disney to plant his theme park there. Las Vegas, a town that had a population of ninety-six people just a century ago, has been the fastest-growing city in the United States over the past decade.

It is easy—and probably not wrong—to be a cynic about the pleasuring grounds of the twenty-first century, at least in the United States and Europe. The revolutionary sentiments that took root at the Green Dragon in Boston are not likely to be stirring at the sports bars that line Fenway; it’s hard to have a multidisciplinary coffeehouse salon when everyone in Starbucks is staring at a laptop, wearing headphones. (The second half of Habermas’s analysis of the public sphere was dedicated to its modern-day demise.) But at least one part of this legacy continues to inspire: the urban parks that were first built in the second half of the nineteenth century, as an outgrowth of our new relationship to nature that de Saussure and the Romantics fostered, and as a reaction to the runaway growth and overcrowding of the new metropolitan centers. These spaces continue to be vital connection points for the many cultural threads that create a great city. Consider Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in the 1860s, after the completion of Manhattan’s Central Park. Walk through the barbecue and picnic areas on a Fourth of July afternoon and it is impossible not to be moved by the exceptional diversity of the city on display: the huge clan of Korean-Americans gathered under an elm tree, with the family of Hasidic Jews strolling down the path behind them; the Puerto Ricans barbecuing up the hill, with the Williamsburg hipsters playing Frisbee between them; the rap and salsa and acoustic guitars; the old couple reading Spanish-language papers on a park bench. There is an entire world hanging out together in a space the size of ten city blocks, and the space is as safe and green and at ease with itself as one could possibly imagine.

Design for Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, circa 1868

No doubt such a scene would have appalled the authorities that condemned John Hughson to death for daring to create establishments where whites and blacks could enjoy their leisure time together; no doubt Charles II would only see “idle and disaffected persons” escaping their “lawful calling and affairs.” But most of us today can appreciate that holiday scene for the extraordinary achievement it is. Once you get past the Macy’s fireworks display, Fourth of July imagery and rhetoric is usually full of old-time Americana: the small town’s one fire truck decked out for the main-street parade, the Little League game, the white picket fences with their patriotic bunting. There is plenty to celebrate about the joys of small communities, but in a way, there is nothing particularly original about that story. World history is teeming with small, successful communities united by a common culture and worldview, after all. What is much rarer is that Fourth of July scene in Prospect Park, and in most urban parks in metropolitan centers around the world. Until modern times, social spaces where all those different groups could happily coexist were almost unheard-of. Today, we take these environments for granted, and rarely celebrate the visionaries that helped bring them into being. But in a way, they are an achievement every bit as impressive as the conventional icons of modern progress: skyscrapers or cell phones or satellites. You can see them as the completion of a project that began thousands of years before, with the global network that first took shape around the spice trade. The taste of clove and nutmeg and pepper compelled human beings to explore the planet and erect markets that stretched to all corners of the globe. Today, that connected world is just down the street from us, reading the paper on a park bench or grilling hot dogs: at peace with itself, and at play.