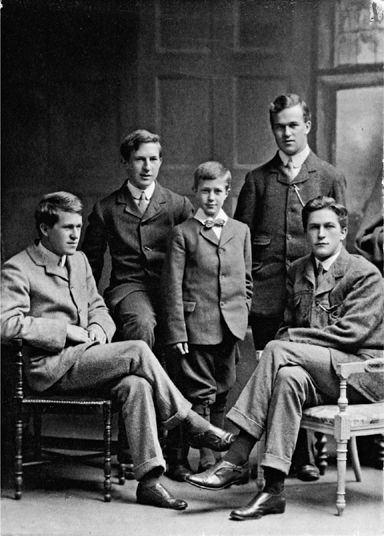

T. E. Lawrence (far left) and his four brothers (left to right): Frank, Arnold, Robert, and Will. While T. E. waged “paper-combat” in Cairo during 1915, both Frank and Will would be killed on the Western Front.

Bodleian ref: MS. Photog. c. 122, fol. 3

Scholar, spy, and notorious ladies’ man: Curt Prüfer in Cairo, 1906

© Trina Prufer

Fallen aristocrat William Yale was the only American intelligence agent in the Middle East during World War I—even while he secretly remained on the payroll of Standard Oil.

© Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library

A towering figure: Aaron Aaronsohn, brilliant scientist, ardent Zionist, and mastermind of the most successful spy ring in the Middle East

All rights are reserved to the Beit Aaronsohn Museum NILI

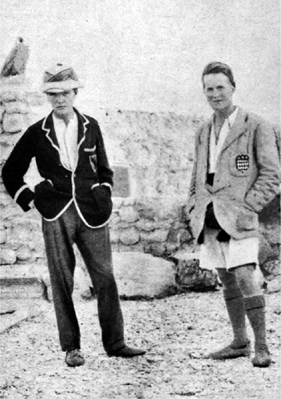

Englishmen abroad: T. E. Lawrence (right) and Leonard Woolley at the archaeological ruins of Carchemish, 1912. Lawrence would recall his time at Carchemish as the happiest of his life.

Stewart Newcombe, Lawrence’s supervisor on the mysterious Wilderness of Zin expedition and the man who brought him to wartime Cairo for intelligence work

© Marist Archives and Special Collections, Lowell Thomas Papers

Dahoum, Lawrence’s young assistant at Carchemish, to whom he dedicated Seven Pillars of Wisdom

© The British Library Board, MS 50584, f.115–116

After his vast family fortune evaporated, William Yale signed on with Standard Oil for a clandestine mission to the prewar Ottoman Empire in search of oil.

© Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library

Playboys in the Holy Land: To keep their mission secret, Yale and his Standard Oil partners (J. C. Hill, second from left, and Rudolf McGovern, second from right) were told to masquerade as wealthy “playboys” on a tour of biblical sights—to limited success.

© Milne Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library

Kaiser Wilhelm II, the Caesar of Germany. A generation of his subjects, including Curt Prüfer, was stirred by Wilhelm’s bellicose demand that Germany assume its rightful “place in the sun.”

“The Kaiser’s spy” and Curt Prüfer’s mentor, Count Max von Oppenheim. While indulging his passion for archaeology, slave girls, and the racetrack, Oppenheim dreamed of setting the Middle East aflame through Islamic jihad.

Prüfer on the eve of the Turkish assault on the Suez Canal, February 1915. Despite predicting disaster in his private diary, he urged the attack forward.

© Trina Prufer

Lord Kitchener, appointed the British war secretary in August 1914. Where others foresaw a quick and painless war, Kitchener predicted one that would sap British manpower “to the last million.”

© UIG History / Science & Society Picture Library

Diplomatic gadfly and amateur extraordinaire Mark Sykes. “The imaginative advocate of unconvincing world movements,” a disdainful Lawrence wrote of Sykes, “a bundle of prejudices, intuitions, half-sciences.”

Reginald Wingate, the sirdar of the Egyptian army and British high commissioner to Egypt. He apparently never figured out T. E. Lawrence’s double cross.

Photo by Hulton Archive/ Getty Images

Ahmed Djemal Pasha (in white coat), the Ottoman governor-general of Syria. Over the course of the war, William Yale, Curt Prüfer, and Aaron Aaronsohn would all have close dealings with the mercurial Djemal.

“The handsomest man in the Turkish army,” Ottoman minister of war Enver Pasha, who conspired with Curt Prüfer to destroy the Suez Canal

© DIZ Muenchen GmbH, Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy

Mustafa Kemal “Ataturk,” the hero of Gallipoli and the founder of the modern Turkish republic

Library of Congress

King Hussein of the Hejaz

© Marist Archives and Special Collections, Lowell Thomas Papers

Ronald Storrs, the liaison in the secret negotiations between Hussein and the British, and the man who brought T. E. Lawrence into the Arab Revolt

© Marist Archives and Special Collections, Lowell Thomas Papers

“The armed prophet,” Faisal ibn Hussein, King Hussein’s third son and T. E. Lawrence’s chief ally during the Arab Revolt

Interminable talks and languorous meals: a tribal council at Faisal’s roving war headquarters, 1917. Unique among his military officer colleagues, Lawrence understood that the British had to adapt to the Arab way of war.

© Marist Archives and Special Collections, Lowell Thomas Papers

With a keen insight into how tribal politics worked, Lawrence was the only British officer in Arabia to be truly accepted into Faisal’s inner circle. Faisal (third from right) and his tribal lieutenants, with Lawrence at lower right.

© Marist Archives and Special Collections, Lowell Thomas Papers

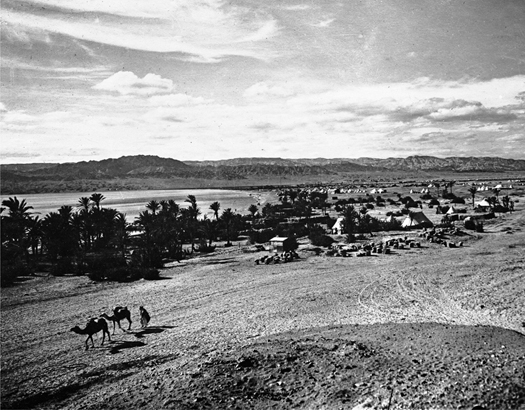

War at its most primal. Lawrence’s decisions on when and where to attack the Turks were largely dictated by the availability of water and forage.

© www.rogersstudy.co.uk. March 1917. Photo by Captain Thomas Henderson

Gilbert Clayton, Britain’s chief spymaster in Egypt and T. E. Lawrence’s supervisor. By autumn 1917, Clayton was so concerned at the risks Lawrence was taking that he planned to remove him from the battlefield, “but the time is not yet, as he is wanted just now.”

A detachment of the Ottoman Camel Corps in southern Palestine, 1916. Until the guerrilla tactics advocated by Lawrence and others were finally adopted, British forces were repeatedly humiliated by the antiquated and outnumbered Turkish army.

Lawrence’s powers of endurance, exemplified by his marathon camel treks, astounded even his hardiest Bedouin companions.

© Imperial War Museum (Q 60212)

A spectacle out of the Middle Ages: Faisal (center in white robe), leading his tribal army for the assault on Wejh

© Imperial War Museum (Q 58863)

The entrance to Aaronsohn’s Jewish Agricultural Experiment Station at Athlit, the headquarters of his NILI spy ring

All rights are reserved to the Beit Aaronsohn Museum NILI

Aaronsohn’s younger sister, twenty-seven-year-old Sarah, masterfully operated the NILI spy ring inside Palestine despite ever-mounting peril.

All rights are reserved to the Beit Aaronsohn Museum NILI

As Germany’s spymaster, Curt Prüfer was one of the most feared figures in the Middle East during World War I, but he never suspected there was a Jewish spy ring operating out of Athlit.

© Trina Prufer

July 6, 1917: In one of the most daring military exploits of World War I, Arab rebels under Lawrence’s leadership captured the strategically vital port of Aqaba.

© Imperial War Museum (Q 59193)

Auda Abu Tayi, a legendary warrior and Lawrence’s chief ally in seizing Aqaba.

© Marist Archives and Special Collections, Lowell Thomas Papers

The British and French hoped to deny their Arab allies control of Aqaba. Without their knowledge, Lawrence devised the audacious scheme for the Arabs to get there first.

© Marist Archives and Special Collections, Lowell Thomas Papers

“We turned our Hotchkiss on the prisoners and made an end of them.” As the war dragged on, Lawrence became an ever more pitiless battlefield commander.

© Marist Archives and Special Collections, Lowell Thomas Papers

A primary target of the British and Arab rebels was the Hejaz Railway, the lifeline of the Turkish army. By his count, Lawrence personally destroyed seventy-nine bridges during the war.

The chessboard changes. The Turks had no answer when the British introduced Rolls-Royce armored cars to the desert campaign.

Faisal ibn Hussein (in the front passenger seat) and other Arab rebel leaders being transported across the desert, 1918

THREE PHOTOS: © Marist Archives and Special Collections, Lowell Thomas Papers

British Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann (left) and Faisal ibn Hussein, June 4, 1918. The following year, with Lawrence as intermediary, the two joined forces at the Paris Peace Conference to call for a combined Arab-Jewish state in Palestine. This effort was ultimately sabotaged by British and French imperial machinations.

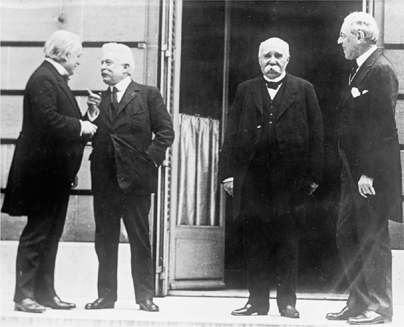

The “Big Four” at the Paris Peace Conference. Left to right, David Lloyd George (Great Britain), Vittorio Orlando (Italy), Georges Clemenceau (France), and Woodrow Wilson (United States). Lloyd George and Clemenceau made a secret pact to divide up the Middle East before Wilson reached Paris. Library of Congress

The betrayal revealed. Lawrence on the balcony of the Victoria Hotel in Damascus, October 3, 1918, after the fateful meeting between Allenby and Faisal. The next day Lawrence would leave Syria, never to return.

© Imperial War Museum (Q 114044)

“I imagine leaves must feel like this after they have fallen from their tree,” Lawrence wrote a friend one week before the motorcycle accident that killed him. This is one of the last formal portraits taken of Lawrence, in December 1934.

Bodleian MS. Photogr. c. 126, fol. 75r