"We have every opportunity and every encouragement before us, to form the noblest, and purest constitution on the face of the earth," revolutionary pamphleteer Tom Paine wrote in late 1775. Paine's words came at a time when the American colonists in their struggle with Great Britain suffered military defeat and economic distress. They were bitterly divided between those who sought independence and those who preferred accommodation. Only thirty-seven years old when he arrived in the United States in 1774, Paine had been a corset maker and minor British government functionary. His best-selling pamphlet Common Sense made an impassioned appeal for independence. It was "absurd," he insisted, for a "continent to be perpetually governed by an island." A declaration of independence would gain for America assistance from England's enemies, France and Spain. It would secure for an independent America peace and prosperity. The colonists had been dragged into Europe's wars by their connection with England. Without such ties, there would be no cause for European hostility. Freed of British restrictions, commerce would "secure us the peace and friendship of all Europe because it is in the interest of all Europe to have America as a free port."1

Paine's call for independence makes clear the centrality of foreign policy to the birth of the American republic. His arguments hinged on estimates of the importance of the colonies in the international system of the late eighteenth century. They suggest the significant role foreign policy would assume in the achievement of independence and the adoption of a new constitution. They set forth basic principles that would shape U.S. foreign policy for years to come. They hint at the essential characteristics of what would become a distinctively American approach to foreign policy. The Revolutionary generation held to an expansive vision, a certainty of their future greatness and destiny. They believed themselves a chosen people and brought to their interactions with others a certain self-righteousness and disdain for established practice. They saw themselves as harbingers of a new world order, creating forms of governance and commerce that would appeal to peoples everywhere and change the course of world history. "We have it in our power to begin the world over again," Paine wrote. Idealistic in their vision, in their actions Americans demonstrated a pragmatism born perhaps of necessity that helped ensure the success of their revolution and the promulgation of the Constitution.2

From their foundation, the American colonies were an integral part of the British Empire and hence of an Atlantic trading community. According to the dictates of mercantilism, then the dominant school of economic thought, the colonies supplied the mother country with timber, tobacco, and other agricultural products and purchased its manufactured goods. But the Americans also broke from prescribed trade patterns. New England and New York developed an extensive illicit commerce with French Canada, even while Britain was at war with France. They also opened a lucrative commerce with Dutch and French colonies in the West Indies, selling food and other necessities and buying sugar more cheaply than it could be acquired from the British West Indies. Americans benefited in many ways from Britain's mercantilist Navigation Acts, but they staunchly resisted efforts to curb their trade with the colonies of other European nations. They became champions of free trade well before the Revolution.3

The American colonies were also part of a Eurocentric "international" community. Formed at the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, this new system sought to end years of bloody religious strife by enlarging the stature and role of the nation-state. Based in part on concepts developed by Hugo Grotius, the Dutch political theorist and father of international law, Westphalia established principles such as the sovereign equality of states, the territorial integrity of the state, non-interference by one state in the domestic affairs of others, peaceful resolution of disputes, and the obligation to abide by international agreements. After Westphalia, diplomacy and war came under the purview of civil rather than religious authority. A corps of professional diplomats emerged to handle interstate relations. A code was produced to guide their conduct. François de Callières's classic manual of the eighteenth-century diplomatic art affirmed that negotiations should be conducted in good faith, honorably, and without deceit—"a lie always leaves a drop of poison behind." On the other hand, spies were essential for information gathering, and bribes—although that word was not used—were encouraged. Negotiation required keen powers of observation, concentration on the task at hand, sound judgment, and presence of mind, de Callières explained. But a "gift presented in the right spirit, at the right moment, by the right person, may act with tenfold power upon him who receives it." It was also important to cultivate the ladies of the court, for "the greatest events have sometimes followed the toss of a fan or the nod of a head."4

Far from eliminating war, the new system simply changed the reasons for fighting and the means of combat. Issues of war and peace were decided on the basis of national interest as defined by the monarch and his court. Nation-states acted on the basis of realpolitik rather than religious considerations, changing sides in alliances when it suited their foreign policy goals.5 Rulers deliberately restricted the means and ends of combat. They had seen the costs and dangers of unleashing the passions of their people. They had made substantial investments in their armies, needed them for domestic order, and were loath to risk them in battle. Once involved in war, they sought to avoid major battles, employed professional armies in cautious strategies of attrition, used tactics emphasizing maneuver and fortification, and held to unwritten rules protecting civilian lives and property. The aim was to sustain the balance of power rather than destroy the enemy. War was to be conducted with minimal intrusion into the lives of the people. Indeed, that master practitioner of limited war, Prussia's Frederick the Great, once observed that war was not a success if most people knew it was going on.

In the international system of the eighteenth century, Spain, the Netherlands, and Sweden, the great powers of an earlier era, were in decline, while France, Great Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia were ascending. Separated by a narrow channel of water, Britain and France were especially keen rivals and fought five major wars between 1689 and 1776. The American colonies became entangled in most of them.

The Seven Years' War, or French and Indian War, as Americas have known it, has been aptly called the "War That Made America."6 That conflict originated in the colonies with fighting between Americans and French in the region between the Allegheny Mountains and the Mississippi River. It spread to Europe, where coalitions gathered around traditional rivals Britain and France, and to colonial possessions in the Caribbean and West Indies, the Mediterranean, the Southwest Pacific, and South Asia. Winston Churchill without too much exaggeration called it the "first world war." After early setbacks in Europe and America, Britain won a decisive victory and emerged the world's greatest power, wresting from France Canada and territory in India and from Spain the territories of East and West Florida, a global empire surpassing that of Rome.7

As is often the case in war, victory came at high cost. Americans had played a major part in Britain's success and envisioned themselves as equal partners in the empire. Relieved of the French and Spanish menace, they depended less on Britain's protection and sought to enjoy the fruits of their military success. The war exhausted Britain financially. Efforts to recoup its costs and to pay the expenses of a vastly expanded empire—by closing off the trans-Appalachian region to settlement, enforcing long-standing trade restrictions, and taxing the Americans for their own defense—sparked revolutionary sentiment among the colonists and their first efforts to band together in common cause. The disparate colonies attempted to apply economic pressures in the form of nonimportation agreements. Twelve colonies sent delegates to a first Continental Congress in Philadelphia in the fall of 1774 to discuss ways to deal with British "oppression." A second Continental Congress assembled in May 1775 as shots were being fired outside Boston.

American foreign relations began before independence was declared. Once war was a reality, colonial leaders instinctively looked abroad for help. England's rival, France, also took a keen interest in events in America, dispatching an agent to Philadelphia in August 1775 to size up the prospects for rebellion. The Americans were not certain how Europe might respond to a revolution. John Adams of Massachusetts once speculated, with the moral self-righteousness that typified American attitudes toward European diplomacy, that it might take generous bribes, a gift for intrigue, and contact with "some of the Misses and Courtezans in keeping of the statesmen in France" to secure foreign assistance.8 About the time French envoy Julien-Alexandre Ochard de Bonvouloir arrived in December, the Continental Congress appointed a Committee of Secret Correspondence to explore the possibility of foreign aid. The committee sounded out Bonvouloir on French willingness to sell war supplies. Encouraged by the response, it sent Connecticut merchant Silas Deane to France to arrange for the purchase of arms and other equipment. Three days before Deane arrived in France, Congress approved a Declaration of Independence designed to bring the American colonies into a union that could establish ties with other nations.9 Whatever place the Declaration has since assumed in the folklore of American nationhood, its immediate and urgent purpose was to make clear to Europeans, especially the French, the colonies' commitment to independence.10

Although their behavior at times suggests otherwise, the Americans were not naive provincials. Their worldview was shaped by experiences as the most important colony of the British Empire, particularly in the most recent war. Colonial leaders were also familiar with European writings on diplomacy and commerce. Americans often expressed moral indignation at the depravity of the European balance-of-power system, but they observed it closely, understood its workings, and sought to exploit it. They turned for assistance to a vengeful France recently humiliated by England and presumably eager to weaken its rival by helping its colony gain independence. Painfully aware of their need for foreign aid, they were also profoundly wary of political commitments to European nations. Conveniently forgetting their own role in provoking the Seven Years' War, they worried that such entanglements would drag them into the wars that seemed constantly to wrack Europe. They feared that, as in 1763, their interests would be ignored in the peacemaking. Americans had followed debates in England on the value of connections with Continental powers. They adapted to their own use the arguments of those Britons who urged avoiding European conflicts and retaining maximum freedom of action. "It is the true interest of America to steer clear of European contentions," Paine advised in Common Sense.11

Americans also agreed that their ties with Europe should be mainly commercial. Through their experience in the British Empire, they had embraced freedom of trade before the publication of Adam Smith's classic Wealth of Nations in 1776. They saw the opportunity to trade with all nations on an equal basis as being in their best interests and indeed essential for their economic well-being. Independence would permit them to "shake hands with the world—live at peace with the world—and trade to any market," according to Paine.12 The enticement of trade would secure European support against Britain. Drawing upon French and Scottish Enlightenment philosophers, some Americans believed that replacement of the corrupt, oppressive, and warlike systems of mercantilism and power politics would produce a more peaceful world. The free interchange of goods would demonstrate that growth in the wealth of one nation would bring an increase for all. The interests of nations were therefore compatible rather than in conflict. The civilizing effect of free trade and the greater understanding among peoples that would come from increased contact would promote harmony among nations.

Keenly aware of their present weakness, the American revolutionaries envisioned future greatness. They embraced views dating back to John Winthrop and the founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony of a city upon a hill that would serve as a beacon to peoples across the world. They saw themselves conducting a unique experiment in self-government that foreshadowed a new era in world politics. As a young man, John Adams of Massachusetts proclaimed the founding of the American colonies as "the opening of a grand scheme and design in Providence for the elimination of the ignorant, and the emancipation of the slavish part of mankind all over the earth." Americans had gloried in the triumph of the British Empire in 1763. When that empire, in their view, had failed them, they were called into being, in the words of patriot Ezra Stiles, to "rescue & reinthrone the hoary venerable head of the most glorious empire on earth." They believed they were establishing an empire without a metropolis, based on "consent, not coercion," that could serve as an "asylum for mankind," as Paine put it, and inspire others to break the shackles of despotism. Through free trade and enlightened diplomacy they would create a new world order.13

Even while Deane was sailing to France in pursuit of money and urgently needed supplies, another committee appointed by Congress was drafting a treaty to be offered to European nations embracing these first precepts of American foreign policy. The so-called Model Treaty, or Plan of 1776, was written largely by John Adams. It would guide treaty-making for years to come. In crafting the terms, Adams and his colleagues agreed as a fundamental principle that the nation must avoid any commitments that would entangle it in future European wars. Indeed, Adams specifically recommended that in dealing with France no political connections should be formed. America must not submit to French authority or form military ties; it should receive no French troops. France would be asked to renounce claims to territory in North America. In return, the Americans would agree not to oppose French reconquest of the West Indies and would not use an Anglo-French war to come to terms with England. Both signatories would agree in the event of a general war not to make a separate peace without notifying the other six months in advance.

The lure to entice France and other Europeans to support the rebellious colonies would be commerce. Since trade with America was a key element of Britain's power, its rivals would not pass up the opportunity to capture it. The Model Treaty thus proposed that trade should not be encumbered by tariffs or other restrictions. Looking to the time when as a neutral nation they might seek to trade with nations at war, Americans also proposed a set of principles advocated by leading neutral nations and proponents of free trade. Neutrals should be free in wartime to trade with all belligerents in all goods except contraband. Contraband should be defined narrowly. Free ships would make free goods; that is to say, cargo aboard ships not at war should be free from confiscation. The Model Treaty was breathtaking in some of its assumptions and principles. Congress approved it in September 1776 and elected Thomas Jefferson of Virginia (who declined to serve) and elder statesman Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia to join Deane in assisting with its negotiation and bringing France into the war. The Americans thus entered European diplomacy as heralds of a new age.14

Not surprisingly, the French were also nervous about close connections. The architect of French policy toward the American Revolution was the secretary of state for foreign affairs, Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes. An aristocrat and career diplomat, Vergennes had spent so much time abroad—more than thirty years in posts across Europe—that a colleague dismissed him as a "foreigner become Minister."15 He was well versed in international politics, cautious by nature, and hardworking. Jefferson said of him that "it is impossible to have a clearer, better argued head." Vergennes's chief concern was to regain French preeminence in Europe.16 He saw obvious advantages in helping the Americans. But he also saw dangers. France could not be certain of their commitment to achieve independence or their ability to do so. He worried they might reconcile with Britain and join forces to attack the French West Indies. He recognized that overt aid to the Americans would give Britain cause for a war France was not prepared to fight. French policy therefore was to keep the rebels fighting by "feeding their courage" and offering "hope of efficacious assistance" while avoiding steps that might provoke war with Britain. The French government through what would now be called a covert operation provided limited, clandestine aid to the rebels. It set up a fictitious trading company headed by Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, a colorful aristocrat and playwright whose comedies like The Barber of Seville poked fun at his own class, and loaned it funds to purchase military supplies from government warehouses to sell the Americans on credit.

Ninety percent of the gunpowder used by the colonists during the first years of the war came from Europe, and foreign aid was thus indispensable from the outset. By the end of 1776, however, it was increasingly apparent that secret, limited aid might not be enough. Early military operations were disappointing, even calamitous. From the outset, Americans believed that other peoples shared their aspirations. Naively assuming that the residents of Canada, many of them French Catholics, would rally to the cause, they invaded Britain's northernmost province in September 1775. Expecting Canada to fall like "easy prey," in George Washington's words, they also grossly underestimated what was required for the task. Nine months later, on the eve of the Declaration of Independence, the disheartened and defeated invaders limped home in disgrace.17 In the meantime, Washington had abandoned New York. His army was demoralized, depleted in numbers, short of food, clothing, and arms, and suffering from desertion and disease. Early military reverses hurt American credit in Europe. Designed to attract foreign support, the Declaration of Independence drew little notice in Europe.18

From the time he landed in Paris, the energetic but often indiscreet Deane compromised his own mission. He cut deals that benefited the rebel cause—and from which he profited handsomely, provoking later charges of malfeasance and a nasty spat in Congress. He was surrounded by spies, and his employment of the notorious British agent Edward Bancroft produced an intelligence windfall for London.19 He recruited French officers to serve in the Continental Army and even plotted to replace Washington as commander. He endorsed sabotage operations against British ports, provoking angry protests to France. Even more dangerously, he and his irascible colleague Arthur Lee made the French increasingly uneasy about supporting the Americans. When Franklin landed in France in December 1776, the Revolution was teetering at home; America's first diplomatic mission was doing as much harm as good.

Franklin's mission to Paris is one of the most extraordinary episodes in the history of American diplomacy, important, if not indeed decisive, to the outcome of the Revolution. The eminent scientist, journalist, politician, and homespun philosopher was already an international celebrity when he landed in France. Establishing himself in a comfortable house with a well-stocked wine cellar in a suburb of Paris, he made himself the toast of the city. A steady flow of visitors requested audiences and favors such as commissions in the American army. Through clever packaging, he presented himself to French society as the very embodiment of America's revolution, a model of republican simplicity and virtue. He wore a tattered coat and sometimes a fur hat that he despised. He refused to powder his hair. His countenance appeared on snuffboxes, rings, medals, and bracelets, even (it was said) on an envious King Louis XVI's chamber pot. His face was as familiar to the French, he told his daughter, as "that of the moon."20 He was compared to Plato and Aristotle. No social gathering was complete without him. To his special delight, women of all ages fawned over "mon cher papa," as one of his favorites called him. A master showman, publicist, and propagandist, Franklin played his role to the hilt. He shrewdly perceived how the French viewed him and used it to further America's cause.21

With independence hanging in the balance, Franklin's mission was as daunting as that undertaken by any U.S. diplomat at any time. Seventy years old when he landed, he suffered the agony of gout. In addition to his diplomatic responsibilities, he bore the laborious and time-consuming responsibilities of a consul. The British were enraged with the mere presence in Paris of that "old veteran in mischief," and repeatedly complained to the comte de Vergennes about his machinations.22 His first goal was to get additional money from the French, a task this apostle of self-reliance must have found unsavory at best. He was also to draw France into a war for which it was not yet ready and for which he had little to offer in return. He went months without word from Philadelphia. Most war news came from British sources or American visitors. He was burdened with the presence in Paris of a flock of rival U.S. diplomats including the near paranoid Lee and the imperious and prickly Adams, both of whom constantly fretted about his indolence and Francophilia. The French capital was a veritable den of espionage and intrigue.

With all this, he succeeded brilliantly. The most cosmopolitan of the founders, he had an instinctive feel for what motivated other nations. He patiently endured French caution about entering the war. A master of what a later age would call "spin," he managed to put the worst of American defeats in a positive light. By displaying his affection for things French and not appearing too radical, he made the American Revolution seem less threatening, more palatable, and even fashionable to the court. He won such trust from his French hosts that they insisted he remain when his rivals and would-be replacements sought to have him recalled. He secured loan after loan from Vergennes, sometimes through tactics that verged on extortion. He repeatedly reminded the French that some Americans sought reconciliation with Britain. In January 1778, he conspicuously met with a British emissary to nudge France toward intervention.

That step came on February 6, 1778, when France and the United States agreed to a "perpetual" alliance. By this time, France was better prepared for war and a bellicose spirit was rising in the country. British, French, and Spanish naval mobilization in the Caribbean raised the possibility that war might engulf the West Indies. A major U.S. victory at Saratoga in upstate New York in October 1777 clinched the decision to intervene. British general John Burgoyne's drive down the Hudson Valley was designed to cut off the northeastern colonies, thereby ending the rebellion. The capture of Burgoyne's entire army at Saratoga destroyed such dreams, bolstered sagging American spirits, and spurred peace sentiments in Britain. It was celebrated in France as a victory for French arms. Beaumarchais was so eager to spread the news that his speeding carriage overturned in the streets of Paris. Franklin's friend Madame Brillon composed a march to "cheer up General Burgoyne and his men, as they head off to captivity."23 Above all, Saratoga provided a convincing and long-sought indication that the Americans could succeed with external assistance, thus easing a French commitment to war.24

Negotiations for the treaty proceeded quickly and without major problems. For the Americans, desperation led pragmatism to win out over ideals. They had long since abandoned their scruples about political connections and their naive belief that trade alone would gain French support. The two nations readily agreed not to conclude a separate peace without each other's consent. Each guaranteed the possessions of the other in North America for the present and forever, a unique requirement for a wartime alliance. For the Americans, the indispensable feature of the agreement was a French promise to fight until their independence had been achieved. The United States gave France a free hand in taking British possessions in the West Indies. The two nations also concluded a commercial agreement, which, while not as liberal as the Model Treaty, did put trade on a most-favored-nation basis, a considerable advance beyond the mercantilist principles that governed most such pacts. Americans wildly celebrated their good fortune. Franklin outdid himself in his enthusiasm for his adopted country. Even the normally suspicious Adams declared the alliance a "rock upon which we may safely build."25

Like all alliances, the arrangement with France was a marriage of expedience, and the two sides brought to their new relationship longstanding prejudices and sharply different perspectives. French diplomats and military officers were not generally sympathetic to the idea of revolution. They saw the United States, like the small nations of Europe, as an object to be manipulated to their own ends. In the best tradition of European statecraft, French diplomats used bribery and other forms of pressure to ensure that the Continental Congress served their nation's interests. French officers in the United States protested that upon their arrival the Americans stopped fighting.26 For their part, Americans complained that French aid was inadequate and French troops did not fight aggressively. They worried that France did not support their war aims. Among Americans, moreover, until 1763 at least, France had been the mortal enemy. As an absolute monarchy and Catholic to boot, in the eyes of many it was the epitome of evil. Americans inherited from the British deep-seated prejudices, viewing their new allies as small and effeminate, "pale, ugly specimens who lived exclusively on frogs and snails." Some expressed surprise to find French soldiers and sailors "as large & as likely men as can be produced by any other nation." Riots broke out in Boston between French and American sailors. In New York, French troops engaged in looting. To avoid such conflict, French officers often isolated their forces from American civilians, sometimes keeping them on board ships for weeks.27

Whatever the problems, the significance of the alliance for the outcome of the Revolution cannot be overstated.28 The timing was perfect. The news arrived in the United States just after the landing of a British peace commission prepared to concede everything but the word independence. The alliance killed a compromise peace by ensuring major external assistance in a war for unqualified independence. Congress celebrated by feting the newly arrived French minister, Conrad Alexandre Gerard, the first diplomat formally accredited to the United States, with food and drink sent by the British commissioners to lubricate the wheels of diplomacy. The French alliance ensured additional money and supplies not only from France but also from other European nations. In all, the United States secured $9 million in foreign military aid without which it would have been difficult to sustain the Revolution. Americans carried French weapons and were paid with money that came from France.29 The French fleet and French troops played a vital role in the decisive battle of Yorktown.

For a steep price—the promise of assistance in the recapture of Gibraltar—France persuaded Spain to enter the conflict. Spain also provided economic and military aid to the United States and drove the British from the Gulf Coast region of North America. A threatened Franco-Spanish invasion of England in 1779 caused panic, making it difficult for the British government to reinforce its navy and troops in North America. The Dutch would also eventually join the allied coalition. An ill-fated British campaign against Dutch colonial outposts in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean diverted attention and precious resources from the American theater. In 1780, Russia's Catherine the Great formed an armed neutrality, a group of nations including Sweden, Denmark, Austria, Prussia, Portugal, and the Kingdom of Naples, who joined together to protect by force, if necessary, neutral shipping from British depredations, helping ensure a flow of supplies to the United States. The Americans were so enthused about the principles of Catherine's program that as a present belligerent but possibly future neutral they tried to join. The French alliance transformed a localized rebellion in North America into a global war that strained even Britain's vast resources and greatly benefited the Americans.30

Even with such support, the war went badly. A French ploy to end the conflict quickly by blockading New York and forcing the surrender of the British army failed miserably. Seeking to exploit widespread Loyalist sentiment, Britain in 1779 shifted to a southern strategy, taking Savannah and later Charleston. British success in the South forced Congress to abandon its scruples against foreign troops, evoking urgent pleas that France send military forces along with its navy. It would be the summer of 1780 before they arrived, however, and in the meantime the U.S. war effort hit a low point. Troops in New Jersey and Pennsylvania revolted. The army was in "extreme distress," in Vergennes's words, and he warned French naval commanders not to land forces if the American war effort seemed about to collapse.31 Chronic money problems required another huge infusion of French funds. By this time, France was also in dire straits militarily. French policymakers briefly contemplated a truce that would have left Britain in control of the southern states.

From Canada to the Floridas, the American Revolution also raged on the western frontier, and here too the war went badly. At the outbreak, the colonists hoped for Native American neutrality. Britain actively sought the Indians' assistance. Perceiving the Americans as the greatest threat to their existence and Britain as the most likely source of arms and protection, most tribes turned to the latter, infuriating the embattled Americans. Adams denounced the Indians as "blood Hounds"; Washington called them "beasts of prey."32 The Americans seized the opportunities created by Indian affiliation with Britain to wage a war of extirpation, where possible driving the Indians further west and solidifying claims to their lands. Even some tribes who collaborated with the Americans suffered at their hands during and after the revolution. "Civilization or death to all American Savages" was the toast offered at a Fourth of July celebration before an American army marched against the Iroquois in 1779.33

This important and often neglected phase of the Revolutionary War began before the Declaration of Independence. In 1774, the governor of Virginia sent an expedition into Shawnee territory in the Ohio Valley, fought a major battle at Point Pleasant on the Ohio River, and forced the Indians to cede extensive land. Three years later, to divert American attention from a British offensive in upstate New York, the British commander at Detroit dispatched Indian raiding parties to attack settlements in Kentucky. Over the next two years, sporadic fighting occurred across the Ohio frontier. The state of Virginia, which had extensive land claims in the region, dispatched George Rogers Clark to attack the British and their Indian allies. In 1778, Clark took forts at Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes. The British retook Vincennes the following year. Clark took it back one more time, but he could not establish firm control of the region. Settlements in Kentucky—the "dark and bloody ground"—came under attack the next two years.

The Americans opened a second front in the war against the Indians in western New York. The Iroquois Confederacy split, some tribes siding with the British, others with the Americans. When Indians working with Loyalists conducted raids across upstate New York in 1778, threatening food supplies vital to his army, Washington diverted substantial resources and some of his best troops to the theater with instructions that the Iroquois should be not "merely overrun but destroyed." In one of the best-planned operations of the war, the Americans inflicted heavy losses on the Iroquois and pushed the frontier westward. But they did not achieve their larger aim of crippling Indian power and stabilizing the region. "The nests are destroyed," one American warned, "but the birds are still on the wing."34 The Iroquois became more dependent on the British and more angry with the Americans. During the remainder of the war, they exacted vengeance along the northern frontier.

The Americans fared best in the South. Although threatened by the westward advance of the Georgia colony, the Creeks clung to their long-standing tradition of neutrality in wars among whites. They also learned valuable lessons from their neighbors, the Cherokees. Having suffered huge losses in the Seven Years' War, the Cherokees welcomed Britain's post-1763 efforts to stop the migration of colonists into the trans-Appalachian West. Out of gratitude for British support and encouraged by British agents, they rose up against the colonists in May 1776. Their timing could not have been worse. Britain had few troops in the southern states at this time. The Americans seized the chance to eliminate a major threat and strengthen their claims to western lands. Georgia and the Carolinas mobilized nearly five thousand men and launched a three-pronged campaign against the Cherokees, destroying some fifty villages, killing and scalping men and women, selling some Indians into slavery, and driving others into the mountains. A 1780 punitive expedition did further damage. The Cherokees would in time re-create themselves and develop a flourishing culture, but the war of American independence cost them much of their land and their way of life.35

Adoption in March 1781 of a form of government—the Articles of Confederation—marked a major accomplishment of the war years, but it did not come easily and proved at best an imperfect instrument for waging war and negotiating peace. Discussion of formal union began in the summer of 1776. Pressures to act intensified in the fall of 1777 when Congress, faced with rising inflation, requested that the states furnish additional funds, stop issuing paper money, and impose price controls. Foreign policy exigencies proved equally important. Optimistic after Saratoga that an alliance with France would be reality, Congress believed that agreement on a constitution would affirm the stability of the new government and its commitment to independence, strengthening its position with other nations. Much like the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation were designed to secure foreign support.36

It took nearly four years to complete a process initiated to meet immediate demands. Congress moved expeditiously, approving a draft on November 15, 1777. The states were forbidden from negotiating with other nations. They could not make agreements with each other or maintain an army or navy without the consent of Congress. On the other hand, the Confederation government could not levy taxes or regulate commerce. It could not make treaties that infringed on the legislative rights of any state. Affirming the principle of state sovereignty, the articles left with the states any powers not "expressly delegated" to the national government. The Congress rejected numerous amendments proposed by the states, but the process took time, and ratification was delayed until March 1781. By that point, many of the deficiencies of the new instrument had been exposed. Congress addressed a most obvious shortcoming, the lack of executive machinery, by creating in 1781 departments for war, finance, and foreign affairs headed by individuals who were not among its members. Robert R. Livingston of New York was named secretary of foreign affairs. Even then, many national leaders believed that the Articles of Confederation were obsolete by the time they had been approved.37

A sudden and dramatic reversal of military fortunes in late 1781 led to negotiations to end the American war. Countering Britain's southern strategy, the United States and France shifted sizeable military forces to Virginia. The French fleet was deployed to the Chesapeake Bay, where the allies in October trapped and forced the surrender of a major British army under the ill-fated Lord Charles Cornwallis on a narrow peninsula along the York River. The victory at Yorktown may have spared the allies from disaster.38 Although Britain still held Charleston and Savannah, Cornwallis's defeat thwarted the southern strategy. It gave a huge boost to faltering American morale and revived French enthusiasm for the war. Yorktown undermined popular support for the war in Britain and, along with the soaring cost of the conflict, caused the fall of the ministry of Lord North and the emergence of a government intent on negotiating with the United States. The war continued for two more years, but after Yorktown attention shifted to the challenging task of peacemaking.

Victory at Yorktown did not give the United States the upper hand in the peace negotiations, however. Washington's army remained short of food, supplies, arms, and ammunition. Britain retained control of some southern states, where fighting still raged. In fact, after Yorktown, the American theater became a sideshow in the global war. In negotiations involving four major nations and numerous lesser ones and a war that stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to South Asia, events in far-flung areas often had a major impact. British setbacks in the Caribbean combined with Yorktown to encourage peace sentiment in England. French naval defeats in the West Indies in the spring of 1782 made Paris more amenable to separate U.S. negotiations with Great Britain.

For the United States, of course, recognition of its independence was the essential condition for peace.39 Independence was the reason the war had been fought, and it formed the indispensable principle of the first statement of war aims drafted in 1779. Congress had hesitated even to raise such issues for fear of exacerbating sectional tensions in wartime. At France's insistence (primarily as a way of bringing U.S. goals into line with its own), the Americans finally did so, and the results made plain the ambitions of the new nation. The territory of the independent republic should extend to the Mississippi River, land that, except for Clark's victories, the United States had not conquered and did not occupy, and to the 31st parallel, the existing border between Georgia and the Floridas. Americans claimed Britain's right acquired from France in 1763 to navigate the Mississippi from its source to the sea.40 They also sought Nova Scotia. New England's fishing industry was valued at nearly $2 million and employed ten thousand men, and access to North Atlantic fisheries comprised a vital war aim.41 In his private and unofficial discussions with British diplomats, Franklin went further. Outraged by the atrocities committed by an enemy he denounced as "the worst and wickedest Nation upon Earth," he urged Britons to "recover the Affections" of their former colonies with a generous settlement including the cession of Canada and the Floridas to the United States.42

In June 1781, again under French pressure and when the war was going badly, Congress significantly modified the instructions to its diplomats in Europe. Reflecting America's dependence on France, the influence of—and bribes provided by—Gerard and his successor, the comte de la Luzerne, and a widespread fear that French support might be lost, the new instructions affirmed that independence should no longer be a precondition to negotiations. The boundaries proposed in 1779 were also deemed not essential. The commissioners could agree to a treaty with Spain that did not provide for access to the Mississippi. In a truly extraordinary provision, Congress instructed the commissioners to place themselves under French direction, to "undertake nothing . . . without their knowledge and concurrence; and ultimately to govern yourselves by their advice and opinion."43 When the military situation changed dramatically after Yorktown, Congress discussed modifying these highly restrictive instructions but did nothing. Fortunately for the United States, its diplomats in Europe ignored them and acted on the basis of the 1779 draft.44

French and Spanish war aims complicated the work of the American peace commissioners. France and especially Spain had gone to war to avenge the humiliation of 1763, weaken their major rival by detaching Britain's most valuable colonies, and restore the global balance of power. France was committed by treaty to American independence, but not to the boundaries Americans sought. Indeed, at various points in the war it was prepared to accept a partition that would have left the southern colonies in Britain's possession. A weaker United States, Vergennes and his advisers reasoned, would be more dependent on France. France did not seek to regain Canada, but it preferred continued British dominance there to keep an independent United States in check. It also sought access to the North Atlantic fisheries.

France's ties with Spain through their 1779 alliance further jeopardized the achievement of U.S. war aims. Although it provided vital assistance to the United States, Spain never consented to a formal alliance or committed itself to American independence. Because France had promised to fight until Spain recovered Gibraltar, America's major war aim could be held hostage by events in the Mediterranean. Spain also sought to recover the Floridas from Britain. Even more than France, it preferred to keep the United States weak and hemmed in as close to the Appalachians and as far north as possible. Spain saw no reason to grant the United States access to the Mississippi.

Ironically, but not surprisingly, given the strange workings of international politics, the United States found its interests more in line with those of its enemy, Great Britain, than its ally, France, and France's ally, Spain. To be sure, Britons acquiesced in American independence only grudgingly. As late as 1782, well after Yorktown, top officials insisted on negotiating on the basis of the uti possidetis, the territory actually held at the time, which would have left Britain in control at least of the southernmost American states. King George III contemplated negotiating with the states individually, a classic divide-and-conquer ploy. The British government would have concluded a separate peace with France if expedient. Even after Lord North resigned in March 1782 and a new government took power, there was talk of an "Irish solution," an autonomous America within the British Empire.45

Gradually, top British officials and especially William Petty Fitzmaurice, the earl of Shelburne, shifted to a more conciliatory approach. Conservative, aloof, and secretive, known for his duplicity, Shelburne was called "the Jesuit of Berkeley Square." He was persuaded to adopt a more accommodating approach by his friend Richard Oswald, a seventy-six-year-old acquaintance and admirer of Franklin. Oswald owned property in the West Indies, West Florida, and the southern colonies. He had lived six years in Virginia. He and Shelburne, in the latter's words, "decidedly tho reluctantly" concluded that Britain's essential aim should be to separate the United States from France. Independence was acceptable if it could accomplish that.46 They hoped that an America free of France through a shared history, language, and culture would gravitate back toward Britain's influence and become its best customer.47

Given the different parties involved and the conflicts and confluences of interests, the peace negotiations were extremely complicated. They resembled, historian Jonathan Dull has written, a "circus of many rings," with all the performers walking a tightrope.48 Military action on land or sea even in distant parts of the globe could tip the balance one way or the other. Europe and America formed a very small world in the 1780s. The key players knew and indeed in some cases were related to each other. Diplomats moved back and forth between London and Paris with relative ease. At one point, two competing British cabinet ministers had representatives in Paris talking to the Americans. In the latter stages, Franklin's fellow commissioners John Adams and John Jay went off in directions that might have been disastrous.

With North's resignation, an unwieldy government headed by Lord Rockingham took power in England. Two men were nominally responsible for negotiations with the Americans, the Whig Charles James Fox, secretary of state for foreign affairs, who favored immediate independence, and the more cautious Shelburne, secretary of state for home and colonial affairs. Before North's resignation, Franklin, through an especially effusive letter of thanks to Shelburne for a gift of gooseberry bushes sent to a friend in France, had hinted that the Americans might negotiate a separate peace. Shelburne agreed that negotiations could begin in France. Not yet in full control, however, he refused to accept independence except as part of a broader settlement. Franklin again pleaded for British generosity, hinting that in return the United States might help end Britain's wars with France and Spain by threatening a separate peace.

The two sides got past the first major hurdle in July 1782. Shelburne maneuvered Fox out of the negotiations and then out of the cabinet. Rockingham died shortly after, making Shelburne head of the cabinet and giving him control over the negotiations. By this time, Shelburne had resigned himself to full American independence. He named Oswald to negotiate with Franklin. Reflecting the new nation's importance in the balance of power, he instructed his envoy that "if America is to be independent, she must be so of the whole world. No secret, tacit, or ostensible connections with France." Shelburne went along with Franklin's ploy not because of the strength of the American's bargaining position but rather because he was eager for peace with France and Spain and agreed with Franklin that peace with the United States could help end the European war. Oswald accepted in principle Franklin's "necessary" terms: complete and unqualified independence, favorable boundaries, and access to the fisheries.49

This left numerous thorny matters unresolved. Britain demanded compensation for property confiscated from those Americans who had remained loyal to the Crown. Americans insisted upon access to the Mississippi. Franklin was furious with Britain's initial reluctance to concede independence and the atrocities he claimed its troops had committed. The fact that his estranged son, William, was a Loyalist gave him a deeply personal reason to oppose for this group the sort of generosity he repeatedly asked of Britain. He exclaimed regarding the Mississippi that "a Neighbour might as well ask me to sell my street Door" as to "sell a Drop of its Waters."50 Initial discussions produced little progress.

From this point, John Jay, and to a lesser extent Adams, replaced Franklin as the primary negotiators. Both men were profoundly suspicious of Britain—and even more of France. Their approach to the negotiations differed sharply from their elder colleague. From the moment he had arrived in Europe in 1778, Adams had raised a ruckus. "Always an honest Man, often a Wise one, but sometimes in some things out of his Senses," Franklin had said of Adams, and in terms of the younger man's service in Paris, the criticism was understated.51 Adams repeatedly complained of "the old Conjurer's" indolence, his "continued Discipation," and his subservience to France. He even accused Franklin of conspiring to get him aboard a ship that was captured by the British. Like other Americans, Adams inherited from the British a deep dislike for France, an "ambitious and faithless nation," he once snarled.52 His staunch republican ideology bred suspicion of all men of power. Adams railed against the "Count and the Doctor." He insisted that France was determined to "keep us poor. Depress us. Keep us weak."53 A descendant of French Protestants, Jay came by his suspicions naturally. They were heightened and his disposition soured by the three frustrating and largely fruitless years he spent in Madrid seeking to persuade Spain to ally with the United States. Adams's and Jay's suspiciousness and their often self-righteous, moralistic demeanor, one suspects, were also born of the anxieties afflicting these neophytes in the settled world of European diplomacy. They protested the immorality of that system, but, given their suspicions, they had no qualms about breaking the terms of their treaty with France and negotiating separately with Britain. Jay arrived in Paris in May 1782, but he was bedridden with influenza for several months. When he recovered and Franklin became deathly ill with kidney stones, he turned his worries on the British. Because Oswald's commission did not mention the United States by name and therefore did not explicitly recognize American independence, Jay broke off talks with England.

Within several weeks even more suspicious of France and Spain, Jay abruptly changed course. The trip of one of Vergennes's top advisers to Britain persuaded him that some nefarious Anglo-French plot was afoot. With the consent of Franklin and the enthusiastic support of Adams, he dropped his demand for prior recognition of U.S. independence at about the time Shelburne was prepared to grant it. He sent word to London that the United States would abandon the alliance with France if a separate peace could be arranged. Oswald's commission was revised to include the name of the United States, thus extending formal recognition of independence. It was a curious and costly victory for the Americans. In the hiatus caused by Jay's breaking off of the discussions, the British lifted Spain's siege of Gibraltar, leaving them in a stronger negotiating position and less eager to end the European war. When the talks resumed, Jay compounded his earlier mistake by conceding on the fisheries. He also devised a harebrained scheme to encourage America's enemy, Britain, to attack its backer, Spain, and retake Pensacola. The proposal undoubtedly reflected Jay's passionate hatred for Spain and perhaps his Anglophilia. Had the British gone along, their position on the Gulf Coast would have been greatly strengthened, threatening the safety of a new and vulnerable republic.54

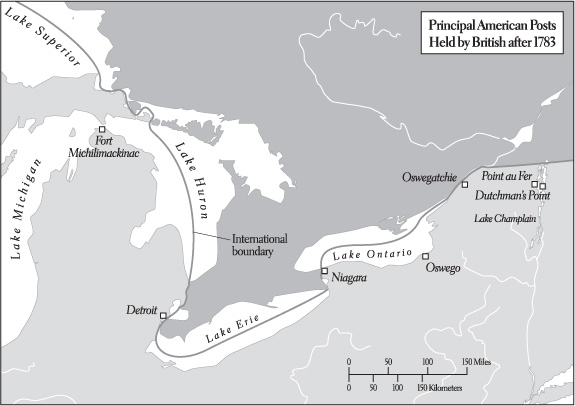

Despite Jay's dubious maneuvers, a peace settlement was patched together in October and November of 1782. Adams and Jay argued interminably over countless issues—"the greatest quibblers I have ever seen," one British diplomat complained.55 In the end, they got much of what they wanted and far more than their 1781 instructions called for. Britain agreed to recognize U.S. independence and withdraw its troops from U.S. territory, the essential concessions. Although many complicated details remained to be worked out, the boundary settlement was remarkably generous given the military situation when the war ended: the Mississippi River in the west; the Floridas in the south; and Canada to the north. Britain extended to the United States its rights to navigate the Mississippi, a concession that without Spain's assent was of limited value. The fisheries were one of the most difficult issues, and the United States could secure only the "liberty," not the right, to fish off Newfoundland and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Other troublesome issues were "resolved" with vague statements that would cause prolonged and bitter disputes. Creditors in each nation were to meet no legal obstacles to the repayment of debts. Congress would recommend to the states the restitution of Loyalist property confiscated during the war.

The American negotiators have often been given the credit for this favorable outcome. They shrewdly played the Europeans against each other, it has been argued, exploiting their rivalries, wisely breaking congressional instructions, and properly deserting an unreliable France to defend their nation's interests and maximize its gains. Such an interpretation is open to question. The Americans, probably from their own insecurities, were anxiety-ridden in dealing with ally and enemy alike.56 Jay's excessive nervousness about England and then his separate approach to that country not only broke faith with a supportive if not entirely reliable ally but also delayed negotiations for several months. It eased pressure on Shelburne to make concessions and left the United States vulnerable to a possible Shelburne-Vergennes deal at its expense. Jay and Adams had reason to question Vergennes's trustworthiness, but they should have informed him of the terms before springing the signed treaty upon him. Ultimately, the favorable settlement owed much less to America's military prowess and diplomatic skill than to luck and chance: Shelburne's desperate need for peace to salvage his deteriorating political position and his determination to settle quickly with the United States and seek reconciliation through generosity.57

News of the preliminary treaty evoked strikingly different reactions among the various parties. Finalization of the terms required a broader European settlement, which would not come until early 1783, but warweary Americans greeted news of the peace with relief and enthusiasm. At the same time, some members of Congress, encouraged by the ardently pro-French Livingston, sought to rebuke the commissioners for violating their instructions and jeopardizing the French alliance. The move failed, but Franklin was sufficiently offended to muse that the biblical blessings supposedly accorded to peacemakers must be reserved for the next life. Britons naturally recoiled at Shelburne's generosity, and the architect of the peace treaty fell from power in early 1783. His departure and British anger at defeat ensured that the generous trade treaty he had contemplated would not become reality. Vergennes was at least mildly annoyed at the Americans' independence, complaining that if it were a guide to the future "we shall be but poorly payed for all we have done for the United States." He was shocked at British generosity—the "concessions exceed all that I should have thought possible."58 He was also relieved that the Americans had freed him of obligations to fight until Spain achieved its war aims and thereby helped him secure the quick peace he needed to address European issues. It was Franklin's task to repair the damage done by Jay and Adams (with his consent, of course) and also to secure additional funds without which, Livingston implored him, "we are inevitably ruined."59 He begged Vergennes's forgiveness for the Americans "neglecting a Point of bienseance." Adding a clever twist, he confided that the British "flatter themselves" that they had divided the two allies. The best way to disabuse them of this notion would be for the United States and France to keep "this little misunderstanding" a "perfect Secret."60 The old doctor even had the audacity to ask for yet another loan. Already heavily invested in his unfaithful allies and hopeful of salvaging something, Vergennes saw little choice but to provide the Americans an additional six million livres.

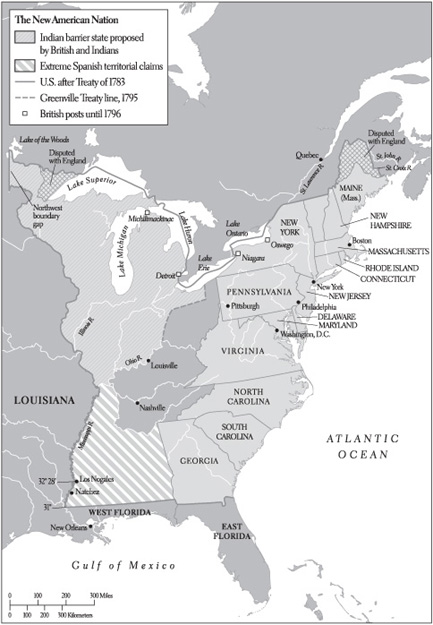

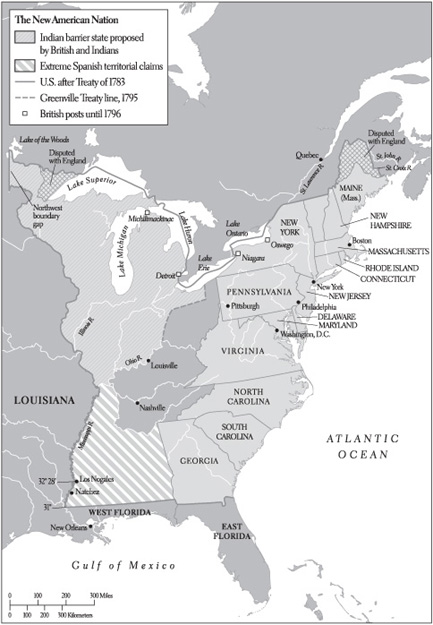

The treaties ending the wars of the American Revolution had great significance for the people and nations involved. Most Native Americans had sided with Britain, but the peace treaty ignored them and assigned to the United States lands they regarded as theirs. "Thunder Struck" when they heard the news, they issued their own declarations of independence, proclaiming, in the words of the Six Nations, that they were a "free People subject to no Power upon Earth."61 For France, an ostensible winner, the war cost an estimated one billion livres, bankrupting the treasury and sparking a revolution that would have momentous consequences in America as well as in Europe. Britain lost a major part of its empire but, ironically, emerged stronger. Its economy quickly recovered, and with the industrial revolution flourished as never before.62 The treaty sealed U.S. independence. The extensive boundaries provided the springboard for continental empire. Americans would quickly learn, however, that securing the peace could be even more difficult than winning the war.

Peace brought scant stability. Debt weighed upon nation and citizens alike. War had ravaged parts of the country. Slaves had been carried off, traditional markets closed, and inflation unleashed. Shortly after the war, the nation plunged into its first full-fledged depression. The economy improved slowly over the next five years, but a Congress lacking real authority could not set economic policies. Wartime unity gave way to snarling rivalry over western lands. Attendance at the Congress was so erratic that there was seldom a quorum. The shift of its meeting place from Philadelphia to Princeton and then to Annapolis, Trenton, and New York City symbolized the instability of the institution and the nation itself.63

Challenges from abroad posed greater threats. The rebelling colonies had exploited European rivalries to secure economic and military aid from France and Spain and a generous peace treaty from Britain. Once the war ended, divisions among the major powers receded along with opportunities for the United States. The Europeans did not formally coordinate their postwar approaches, but their policies were generally in tandem. They believed that the United States, like republics before it, would collapse of its own weight. The sheer size of the country worked against it, according to Britain's Lord Sheffield. The "authority of Congress can never be maintained over those distant and boundless regions." Some Britons even comforted themselves that their generosity at the peace table would hasten America's downfall; the time often estimated was five years.64 A French observer speculated that the whole "edifice would infallibly collapse if the weakness of its various parts did not assure its continuance by making them weigh less strongly the ones over the others."65

Europeans were not disposed to help the new nation's survival. To keep it weak and dependent, they imposed harsh trade restrictions and rebuffed appeals for concessions. Britain and Spain blocked the United States from taking control of territory awarded in the 1783 treaty. Lacking the means to retaliate and divided among themselves on foreign policy priorities, Americans were powerless to resist European pressures. More than anything else, their inability to effectively address crucial foreign policy problems persuaded many leaders that a stronger central government was essential to the nation's survival.

One area of progress was in the administration of foreign affairs. Livingston had repeatedly complained of inadequate authority and congressional interference. He resigned before the peace treaty was ratified. Congress responded by strengthening the position of the secretary for foreign affairs. John Jay assumed the office in December 1784 and held it until a new government took power in 1789, providing needed continuity. An able administrator, he insisted that his office have full responsibility for the nation's diplomacy. Remarkably, he also conditioned his acceptance on Congress settling in New York.66 Assisted by four clerks and several part-time translators, he worked out of two rooms in a tavern near Congress's meeting place. He did not achieve his major foreign policy goals, but he managed his department efficiently. Interestingly, a secret act of Congress authorized him to open and examine any letters going through the post office that might contain information endangering the "safety or interest of the United States." He appears not to have used this authority.67

Americans and Europeans confronted each other across a sizeable divide, the product of experience and ideology clearly reflected in diplomatic protocol. Upon arriving as U.S. envoy in England, John Adams quickly wearied of affairs at the Court of St. James's. Good republican—and New Englander—that he was, he complained to Jay after an audience with George III that the "essence of things are lost in Ceremony in every Court of Europe." But he responded pragmatically. The United States must "submit to what we cannot alter," he added resignedly. "Patience is the only Remedy."68 Troubled by the meddling of French diplomats in the United States during the Revolution, Francis Dana, minister to Russia in 1785, urged that the United States abandon diplomacy altogether, warning that "our interests will be more injured by the residence of foreign Ministers among us, than they can be promoted by our Ministers abroad."69 Americans were much too worldly and practical to go that far, but they did incorporate their republicanism into their protocol and sought to shield themselves from foreign influence. Foreign diplomats were required to make the first visit to newly arriving members of Congress, a sharp departure from European practice. Congressmen made sure never to meet with the envoys by themselves. The "discretion and reserve" with which Americans treated representatives of other countries, a French diplomat complained, "appears to be copied from the Senators of Venice." The "outrageous circumspection" with which Congressmen behaved "renders them sad and silent." Like Adams, the Frenchman saw no choice but to adapt. "Congress insists on the new etiquette," French diplomat Louis Guillaume Otto sighed, "and the foreign Ministers will be obliged to submit to it or to renounce all connection with Members of Congress."70

The most pressing issue facing the United States during the Confederation period was commerce. Americans took pride in their independence, but they recognized that economically they remained part of a larger trading community. "The fortune of every citizen is interested in the fate of commerce," a congressional committee reported in 1784, "for it is the constant source of industry and wealth; and the value of our produce and our land must ever rise or fall in proportion to the prosperous or adverse state of our trade."71 In a world of empires, the republic had to find ways to survive. Americans had often protested the burdens imposed by the Navigation Acts, but they had also benefited from membership in the British Empire. They hoped to retain the advantages without suffering the drawbacks. They assumed that their trade was so important that other nations would accept their terms. In fact, the Europeans and especially Britain set the conditions. And the competition among regions, states, and individuals prevented Congress from agreeing on a unified trade policy.72

Shelburne's fall from power brought a dramatic shift in British commercial policy. The change toward a hard line reflected persisting anger with the colonies' rebellion, their victory in the war, and what many Britons believed were overly generous peace terms. Despite Adam Smith's fervent advocacy of free trade, the Navigation Acts remained central to British economic thinking. British shipping interests especially feared American postwar competition. The influential Sheffield insisted that since the Americans had left the empire they must be treated as foreigners. This "tribune of shipbuilders and shipowners" argued that America's dependence on British credit and its passion for British manufactures would force trade back into traditional channels. London could fix the terms. On July 2, 1783, ironically the seventh anniversary of Congress's initial resolution for independence, Parliament issued an order in council excluding U.S. ships from the West Indies trade. British policymakers hoped that the rest of the empire could replace the Americans in established trade channels. That did not happen, but the 1783 order devastated New England's fishing and shipping industries. Britain also exploited U.S. removal of wartime trade restrictions and Congress's inability to agree on a tariff to flood the U.S. market with manufactured goods. It restricted the export of any items that would help Americans create their own manufactures. Britain's harsh measures contributed significantly to the depression that caused ruin across the nation.73

John Adams assumed the position of minister to England in June 1785 with instructions to press for the elimination of trade restrictions and secure an equitable commercial treaty. Adams sought to hit the British where it hurt, repeatedly warning that the effect of their trade restrictions was to "incapacitate our Merchants to make Remittances to theirs." He carried on a "Sprightly Dialogue" with Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger on trade and other matters and attributed British commercial restrictions to jealousy.74 After six months, he admitted that he was a "cypher" and that the British were determined to reduce the United States to economic bondage.75 Minister to France Thomas Jefferson, who joined Adams in London in 1786, flatly labeled the British "our enemies," complaining that they were "more bitterly hostile to us at present than at any point of the late war." British officials responded to American appeals, he added, by "harping a little on the old String, the insufficiency of the powers of Congress to treat and to compel Compliance with the Treaties."76 Adams occasionally threatened a Navigation Act discriminating against British imports, but he knew, as did Jay, that such a measure could not be enacted or enforced by a government operating under a constitution that left powers over commerce to the states.

The United States fared little better with other major European powers. Americans hoped that the enticement of their bounteous trade, long circumscribed by British regulations, would lure Spain and France into generous commercial treaties. Spain did open some ports to the United States. Spanish products entered American ports on a de facto most-favored-nation basis. But Spain refused a commercial treaty without U.S. concessions in other areas. More important, once the war ended, Spain closed the ports of Havana and New Orleans to U.S. products and denied Americans access to the Mississippi River.

Of all the European nations, France was the most open to U.S. trade, but this channel failed to meet expectations. Jefferson succeeded the estimable Franklin as minister to France in 1784, "an excellent school of humility," he later mused, and ardently promoted expanded trade with France.77 The Virginian's cosmopolitan tastes, catholic interests, and aristocratic manners made him a worthy successor and also a hit at court. He believed that if the United States shifted its trade to the French West Indies and opened its ports to French products, British dominance of U.S. commerce could be broken. With his customary attention to detail, Jefferson studied possible items of exchange, urging the French to convert to American whale oil for their lamps and American rice farmers to grow varieties the French preferred. French officials, Vergennes included, went to some lengths to encourage trade, dispatching consuls to most American states and opening four ports to U.S. products. Responding to domestic and colonial interest groups, the French also closed off the French West Indies to major U.S. exports such as sugar and cotton and imposed tariffs on imports of American tobacco. Jefferson pushed for concessions. "If France wishes us to drink her wine," he insisted, "she must let her Islanders eat our bread."78 But the barriers to trade were greater than the concessions on each side. The French lacked the capital to provide the credits American merchants needed to import their products. France refused to adapt products to American tastes and could not produce others in quantities needed to satisfy American demands. Despite strong efforts from both countries, the trade remained limited to small quantities of luxury goods, wine, and brandy.

The so-called Barbary pirates posed another impediment to commerce. For years, the North African states of Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli had earned a lucrative take by plundering European ships, ransoming or enslaving captive sailors, and extorting from seafaring nations handsome annual fees for safe passage through the Mediterranean. It "was written in their Koran," a Tripolitan diplomat instructed Adams and Jefferson, "that all nations who should not have acknowledged their authority were sinners, that it was their right and duty to make war upon them wherever they could be found, and that every [Muslim] who should be slain in battle was sure to go to paradise."79

The Europeans generally found it cheaper to pay than to subdue the pirates by force. As part of the empire, Americans had British protection, and they earned significant profits selling flour, fish, and timber to Mediterranean ports. Jay sought unsuccessfully to get protection for American ships and seamen written into the peace treaty. Once independent, the Americans had to fend for themselves, and the trade was hampered by attacks from the Barbary States. In late 1783, Morocco and Algiers seized three ships and held the crews for ransom. "Our sufferings are beyond our expressing or your conception," an enslaved captive reported to Jefferson.80 Congress put up $80,000 to free the captives and buy a treaty, a princely sum given the state of the U.S. treasury but not nearly enough to satisfy the captors. Like the Europeans, Adams believed it cheaper to pay than to fight. Jefferson became "obsessed" with the pirates, preferring to cut "to pieces piecemeal" this "pettifogging nest of robbers."81 In truth, Congress had neither the money nor will to do either. It appealed to the states for funds with no results. Diplomat Thomas Barclay managed to negotiate without tribute a treaty with the emperor of Morocco, mainly because that ruler disliked the British. Otherwise, problems with the Mediterranean trade were left for another day.

The new nation enjoyed some successes during the Confederation period. The small concessions made by some European states were quite extraordinary in terms of eighteenth-century commercial policies.82 The United States negotiated agreements with Sweden and Prussia based on the liberal principles of the 1776 Model Treaty. Enterprising merchants actively sought out new markets. In August 1784, after a voyage of six months, the Empress of China became the first American ship to reach the port of Canton, where it exchanged with Chinese merchants pelts and "green gold," the fabled root ginseng believed to restore the virility of old men, for tea, spices, porcelain, and silk. The voyage earned a profit of 25 percent, and the ship's return to New York in May 1785 excited for the first time what would become perennial hopes among U.S. merchants of capturing the presumably rich China market. At first unable to distinguish Americans from the British, Chinese merchants were also enthused by the prospect of trade with these "New People" upon seeing from a map the size of this new country.83 American shippers continued to perfect the fine art of evading European trade restrictions. Especially in the West Indies, they employed various clever schemes to get around the British orders in council, developing a flourishing illicit traffic that even the brilliant young naval officer Horatio Nelson could not stop. Commerce increased steadily during these years, and the United States eased out of the depression, but trade never attained the heights Americans had hoped. To many leaders, the answer was a stronger federal government with authority to regulate commerce and retaliate against those nations who discriminated against the United States.

A second major postwar problem was the windfall the nation acquired from England in the 1783 treaty, the millions of acres of sparsely settled land between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. This bounty made the United States an instant great power, but taking control of it and administering it posed enormous challenges. Many of the states held conflicting titles to western lands; Congress's authority was at best uncertain. Already forced westward by the advance of colonial settlements, Native Americans also claimed land in the trans-Appalachian West and were determined to fight for it. They gained support from the British, who hung on to forts granted the United States in the 1783 treaty, and from the Spanish in the Southwest. The problem was complicated when Americans after independence poured westward. The population of Kentucky, according to one estimate, totaled but 150 men in 1775. Fifteen years later, it exceeded 73,000 people. The "seeds of a great people are daily planting beyond the mountains," Jay observed in 1785.84

Among the major accomplishments of the Confederation government were the establishment of federal authority over these lands and creation of mechanisms for settling and governing the new territory. The issue of federal versus state control was resolved during the war when the states ceded their land claims to the national government as a condition for adoption of the Articles of Confederation. Virginia had proposed in 1780 that the lands acquired by the national government should be "formed into distinct republican states, which shall become members of the federal union, and have the same rights of sovereignty, freedom, and independence, as the other states."85 Fearful of the proliferation of thinly populated and weak states with loose bonds to the Confederation, Congress in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, its most important achievement, put settlement and economic development before statehood. The ordinance did not permit immediate admission to the Union but placed the new settlements under what Virginian James Monroe admitted were "Colonial principles." It did guarantee for those in the territories the fundamental rights and liberties of American citizens and eventual acceptance into the United States on an equal basis with the other states. It became the means by which territory beyond the Mississippi would be incorporated into the Union.86

It was one thing to plan for governing and incorporating this territory, quite another to control it, and here the Confederation government was far less successful. Continued rapid settlement of the West and effective use of the land required protection from Indians and Europeans and

access to markets. The government could provide neither, encouraging among settlers in the western territories rampant disaffection and even secessionist sentiment.

The state and national governments first addressed the Indian "problem" with a massive land grab. Americans rationalized that since most of the Indians had sided with the British they had lost the war and therefore their claim to western lands. The state of New York took 5.5 million acres from the Oneida tribe, Pennsylvania a huge chunk from the Iroquois. Federal negotiators dispensed with the elaborate rituals that had marked earlier negotiations between presumably sovereign entities and instead treated the Indians as a conquered people. The British had not told the Indians of their territorial concessions to the Americans. The Iroquois came to negotiations at Fort Stanwix in October 1784 believing that the lands of the Six Nations belonged to them. Displaying copies of the 1783 treaty awarding the territory to the United States, federal negotiators informed them: "You are a subdued people. . . . We shall now, therefore declare to you the condition, on which alone you can be received into the peace and protection of the United States." In the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the Iroquois surrendered claims to the Ohio country.87 Federal agents negotiated similar treaties with the Cherokees in the South and acquired most Wyandot, Delaware, Ojibwa, and Ottawa claims to the Northwest.

Such heavy-handed tactics provoked Indian resistance. Native American leaders countered that, unlike the British, they had not been defeated in the war. Neither had they consented to the treaty. Britain had "no right Whatever to grant away to the United States of America, their Rights or properties."88 Leaders such as the Mohawk Joseph Brant and the Creek Alexander McGillivray, both educated in white schools and familiar with white ways, found willing allies in Britain and Spain. Brant secured British backing to build a confederacy of northern Indians to resist American expansion. The Creeks had long considered themselves an independent nation. They were stunned that the British had given away their territory without consulting them. McGillivray tried to pull the Creeks together into a unified nation to defend their independence against the United States. In a 1784 treaty negotiated at Pensacola, he gained Spanish recognition of Creek independence and promises of guns and gunpowder. For the next three years, Creek warriors drove back settlers on western lands in Georgia and Tennessee.89 By the late 1780s, the United States faced a full-fledged Indian war across the western frontier.