During a tense exchange on January 27, 1821, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and the British minister to the United States, Stratford Canning, debated the future of North America. Emphasizing the extravagance of Britain's worldwide pretensions, Adams pointedly remarked: "I do not know what you claim nor what you do not claim. You claim India; you claim Africa; you claim—" "Perhaps," Canning sarcastically interjected, "a piece of the moon." Adams conceded he knew of no British interest in acquiring the moon, but, he went on to say, "there is not a spot on this habitable globe that I could affirm you do not claim." When he dismissed Britain's title to the Oregon country, implying doubts about all its holdings in North America, an alarmed Canning inquired whether the United States questioned his nation's position in Canada. No, Adams retorted. "Keep what is yours and leave the rest of the continent to us."1

That a U.S. diplomat should address a representative of the world's most powerful nation in such tones suggests how far the United States had come since 1789 when Britain refused even to send a minister to its former colony. Adams's statement also expressed the spirit of the age and affirmed its central foreign policy objective. Through individual initiative and government action, Americans after the War of 1812 became even more assertive in foreign policy. They challenged the European commercial system and sought to break down trade barriers. Above all, they poised themselves to take control of North America and seized every opportunity to remove any obstacle. Indeed, only to the powerful British would they concede the right to "keep what is yours." They gave Spaniards, Indians, and Mexicans no such consideration.

The quest for continental empire took place in an international setting highly favorable to the United States. Through the balance-of-power system, the Europeans maintained a precarious stability for nearly a century after Waterloo. The absence of a major war eased the threat of foreign intervention that had imperiled the very existence of the United States during its early years. Europe's imperial urge did not slacken, and from 1800 to 1878 the amount of territory under its control almost doubled.2 But the focus shifted from the Americas to Asia and Africa. The Europeans accorded the United States a newfound, if still grudging, respect. Britain and, to a lesser extent, France clung to vague hopes of containing U.S. expansion but exerted little effort to do so. Periodic European crises distracted them from North America. The vulnerability of Canada and growing importance of U.S. raw materials and markets to Britain's industrial revolution constrained its interference. While Americans continued to fret nervously about the English menace, the Royal Navy protected the hemisphere from outside intervention, freeing the United States from alliances and a large military establishment. The nation enjoyed a rare period of "free" security in which to develop without major external threats.3

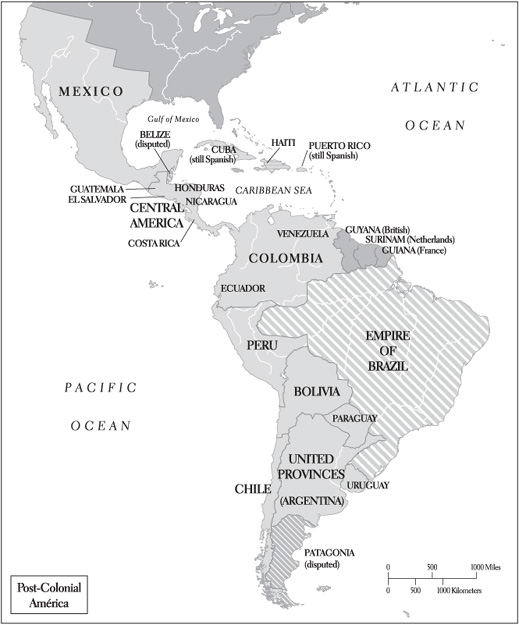

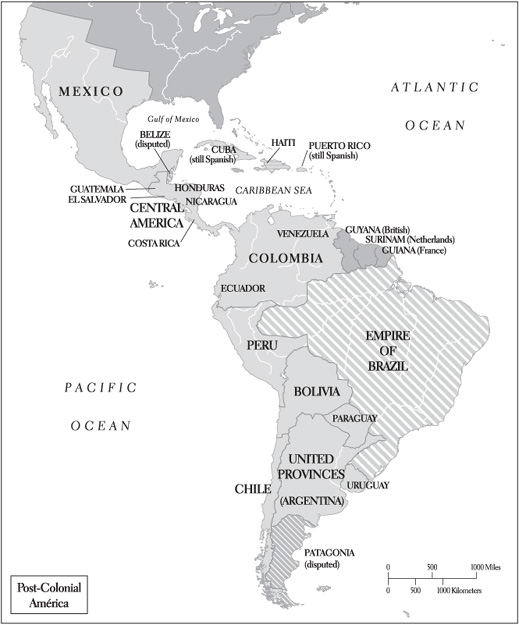

Revolutions in South America during and after the Napoleonic wars provided opportunities and posed dangers for the United States. Sentiment for independence had long simmered on the continent. When Napoleon took control of Spain and Portugal in 1808, rebellion erupted. A new republic emerged in Buenos Aires. Revolutionary leaders Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Miranda led revolts in Colombia and Venezuela, forming a short-lived republic of New Granada. After 1815, revolutions broke out in Chile, Mexico, Brazil, Gran Colombia, and Central America. Many North Americans sympathized with the revolutions. Speaker of the House Henry Clay hailed the "glorious spectacle of eighteen millions of peoples, struggling to burst their chains and to be free."4 Some saw opportunities for a lucrative trade. Preoccupied with its own crises and eager to gain Spanish territory, the United States remained neutral, but in a way that favored the rebellious colonies. Madison and Monroe cautiously withheld recognition. United States officials feared Spain might attempt to recover its colonies or Britain might seek to acquire them, threatening another round of European intervention.

After 1815, the United States surged to the level of a second-rank power. By 1840, much of the territory extending to the Mississippi River had been settled; the original thirteen states had doubled to twenty-six. As the result of immigration and a high birth rate—what nationalists exuberantly labeled "the American multiplication table"—a population that had doubled

between 1789 and 1815 doubled again between 1820 and 1840. Despite major depressions in 1819 and 1837, the nation experienced phenomenal economic growth. An enterprising merchant marine monopolized the coastal trade and challenged Britain's preeminence in international commerce. Wheat and corn production proliferated in the Northwest. Cotton supplanted tobacco as the South's staple crop and the nation's top export. The cotton boom resuscitated a moribund institution of slavery and added pressures for territorial expansion. Indeed, slavery and expansion merged in the prolonged political crisis over admission of Missouri to the Union in 1819—Thomas Jefferson's "fire bell in the night" that raised in a more ominous form the old threat of disunion. The crisis was resolved and disunion perhaps thwarted by the Missouri Compromise of 1820 that admitted Maine as a free state and Missouri as a slave state and prohibited slavery in the Louisiana Purchase territory north of 36° 30'.

Between 1820 and 1840, the U.S. economy began to mature. Construction of roads and canals brought scattered communities together and, along with the steamboat, shrank distances. These innovations dramatically transformed the predominantly agricultural, subsistence economy of Jefferson's time. Americans increasingly prided themselves on political separation from Europe, but the United States was an integral part of an Atlantic-centered international economy. European capital and technology fueled U.S. economic growth. Particularly in agriculture, the nation produced far more than could be consumed at home. Commerce with Europe remained essential to its prosperity.5

Purposeful leaders actively employing the organized power of the national government pushed this process along. Republican ideology was tempered by the exigencies of war. Shortages of critical items forced even Jefferson to concede the necessity of manufactures. Clay went further, promoting an "American System" that aimed at national self-sufficiency by developing domestic manufactures and expanding the home market through such Federalist devices as protective tariffs, a national bank, and federally financed internal improvements. Some Republicans clung to the Jeffersonian vision of a virtuous republic of small farmers. But with the market revolution, new National Republicans dreamed of national wealth and power based on commercial and territorial expansion. Like Clay, they adopted a neo-mercantilist approach that sought to expand exports of agricultural and raw materials and protect domestic manufactures through tariffs.6

The War of 1812 gave a tremendous boost to nationalism. Americans entered the postwar era more optimistic than ever. Their faith in themselves and their nation's destiny knew few bounds. Their boastful pride in their own institutions often annoyed visitors. "A foreigner will gladly agree to praise much in their country," the perceptive Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville complained, "but he would like to be allowed to criticize something and that he is absolutely refused." "I love national glory," one congressman exulted.7 American horizons broadened. Even the optimistic Jefferson could envision nothing more than a series of independent republics in North America. His successor as the architect of U.S. expansion, John Quincy Adams, foresaw a single nation stretching from Atlantic to Pacific. As secretary of state and president he worked tirelessly to realize this destiny.

The quality of American statecraft remained high in the postwar era. Most policymakers had acquired practical experience in the school of diplomatic hard knocks. Cosmopolitan representatives of a still provincial republic, they generally acquitted themselves with distinction. The last—usually viewed as the least—of the Virginia Dynasty, James Monroe was an experienced and capable diplomatist. Described by contemporaries as a "plain man" with "good heart and amiable disposition," he was industrious, a shrewd judge of people and problems, and excelled at getting strong-willed men to work together.8

Monroe's secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, towered above his contemporaries and is generally regarded among the most effective of all those who have held the office. The son of a diplomat and president, Adams brought to his post a wealth of experience and extraordinary skills. He knew six European languages. His seventeen years abroad gave him unparalleled knowledge of the workings of European diplomacy. A man of prodigious industry, he oversaw, with the assistance of eight clerks, the workings of the State Department, writing most dispatches himself and creating a filing system that would be used until 1915. He regularly rose before dawn to pray. His early morning swims in the Potomac, clad only in green goggles and a skullcap, were the stuff of Washington legend. Short, stout, and balding, with a wandering eye—his frequent adversary Stratford Canning called him "Squinty"—Adams could be cold and austere. Throughout his life, he struggled to live up to the high expectations set by his illustrious parents, John and Abigail. Haunted by self-doubt and fears of failure, he drove himself relentlessly. He was proud that his foes found him an "unsocial savage." Through force of intellect and mastery of detail he was a diplomat of enormous skill.9

Adams was also an ardent expansionist whose vision of American destiny was well ahead of his time. A profoundly religious man, he saw the United States as the instrument of God's will and himself as the agent of both. Sensitive to the needs of the shipping and mercantile interests of his native New England, he viewed free trade as the basis for a new global economic order. He fought doggedly to break down mercantilist barriers. His vision extended literally to the ends of the earth. He relished in 1820 the possibility of a confrontation with Britain over newly discovered Graham Land on the northwest coast of Antarctica, a region he conceded was "something between Rock and Iceberg."10

The focus of Adams's attention was North America. As early as 1811, he had foreseen a time when all of the continent would be "one nation, speaking one language, professing one general system of religious and political principles, and accustomed to one general tenor of social usage and customs." That the United States in time should acquire Canada and Texas, he believed, was "as much the law of nature as that the Mississippi should flow to the sea." He told the cabinet in 1822 that "the world should become familiarized with the idea of considering our proper dominion to be the entire continent of North America." As secretary of state, he took giant steps toward achieving that goal. As president from 1825 to 1829, he—with his own secretary of state, Clay—continued to pursue it.11

Monroe introduced important modifications to U.S. diplomatic practice. In keeping with republican principles, he instructed his envoys to "respectfully but decisively" decline the gifts that were the lubricant of European diplomacy. Adams recommended that individuals who had served abroad for more than six years should return home to be "new tempered."12 At the same time, Monroe had suffered numerous slights at the hands of the great powers during his own diplomatic career, and he was eager to command their respect. Persuaded that Jefferson's pell-mell "protocol" had lowered American prestige among Europeans, he reverted to the more formal practice of Washington, receiving foreign envoys by appointment and in full diplomatic dress. U.S. diplomats wore a "uniform," a blue cloth coat with silk lining and gold or silver embroidery, and a plumed hat. When Monroe took office, the capital still showed scars of the British invasion. When he left, the city's appearance and social life had begun to rival European capitals, achieving a "splendour which is really astonishing," according to one American participant. As much as Jefferson's style had symbolized the republican simplicity of an earlier era, Monroe's marked the rise of the United States to new wealth and power.13

The formulation of policy changed little under Monroe and Adams. Monroe employed Washington's cabinet system, submitting major foreign policy issues for the full consideration of department heads. The demise of Federalism after 1815 left only one party for the next decade, but foreign policy remained an area of heated political battle. The so-called Era of Good Feelings was anything but. Throughout the administrations of Monroe and Adams, ambitious cabinet members exploited foreign policy issues to gain an edge on potential rivals. As the economy expanded and diversified, interest groups pushed their demands on the government. In the 1820s, foreign policy, like everything else, became locked in the bitter sectional struggle over slavery. By 1824, partisan politics was back with a vengeance as the followers of war hero Andrew Jackson challenged the Republican ascendancy.

Monroe's and Adams's administrations set commercial expansion as a paramount goal and employed numerous distinctly unrepublican measures to achieve it. Abandoning Jefferson's disdain for diplomats, they expanded the number of U.S. missions abroad. Between 1820 and 1830, they almost doubled the number of consuls, many of them assigned to the newly independent governments of Latin America. These men performed numerous and sometimes difficult tasks, looking after the interests of U.S. citizens and especially merchants, negotiating trade treaties, and seeking out commercial opportunities. When fire devastated Havana, Cuba, in 1826, for example, consul Thomas Rodney alerted Americans to the newly created market for building materials.14 The National Republicans also put aside traditional fears of the navy, maintaining a sizeable fleet after the War of 1812 and employing it to protect and promote U.S. commerce. Squadrons of small, fast warships were posted to the Mediterranean, the West Indies, Africa, and the Pacific, where they defended U.S. shipping from pirates and privateers, policed the illegal slave trade, and looked for new commercial opportunities. While sailing the Pacific station during the 1820s, Thomas ap Catesby Jones, commander of the USS Peacock, negotiated trade treaties with Tahiti and the Hawaiian Islands.15

Monroe and Adams also pushed to secure payment of claims from the spoliation of American commerce, not simply for the money but also as a matter of principle. Payment of such claims would at least imply endorsement of the U.S. position on free trade and neutral rights. The United States pressed France for payment of more than $6 million for seizure of ships and cargoes under Napoleonic decrees and sought additional claims against smaller European states acting under French authority. It tried to collect money from Russia and, during Adams's presidency in particular, from the Latin American governments, most of the claims arising from privateering and other alleged violations of neutral rights by governments or rebels or in disputes between governments during the wars of independence. United States diplomats vigorously defended the nation's interests. Before demanding his passports (a diplomatic practice indicating extreme displeasure that often preceded the breaking of relations), the colorful consul to Rio de Janeiro, Condy Raguet, exclaimed that if U.S. ships wanted to break Brazil's blockade of the Rio de la Plata they would not ask permission and would be stopped only "by force of balls."16

Monroe and Adams used reciprocity as a major weapon of commercial expansion. In its last days, the Madison administration launched an all-out attack on the restrictive trading policies of the European powers. Responding to the president's call to secure for the United States a "just proportion of the navigation of the world," Congress in 1815 enacted reciprocity legislation that legalized the program of discrimination Jefferson and Madison had advocated since 1789. Passed in a mood of exuberant nationalism, the measure made the abolition of discriminatory duties and shipping charges contingent on similar concessions from other countries. Reciprocity was designed to strengthen the hands of U.S. diplomats in negotiations with European powers. As opposed to the most-favored-nation principle, the basis for earlier treaties, it provided, in Clay's words, a "plain and familiar rule" for the two signatories, uncomplicated by deals with other nations, thus reducing the chances for misunderstanding and conflict.17 Reciprocity also made clear U.S. willingness to retaliate. Americans and Europeans increasingly recognized, moreover—the latter sometimes to their chagrin—that reciprocity did not always operate equally on all parties. Such was the superiority of the U.S. merchant marine and mercantile skill that often, as a diplomat pointed out, American shippers could secure a monopoly of trade "whenever anything like fair and equal terms [are] extended to us."18 Through the 1820s, the United States used reciprocity to break down European commercial restrictions and gain access on favorable terms to newly opened markets in Latin America and elsewhere across the world.

For the effort expended, the Monroe-Adams trade offensive produced limited results. The United States settled a small claims dispute with Russia, but not much else. Negotiations with France provoked a nasty diplomatic spat. The United States pushed these claims with great vigor, at one point even discussing naval retaliation. Their treasury exhausted from years of war, the French perceived that if they paid the United States other claimants would get in line. Thus they stalled, reminding U.S. officials that loans made by French citizens during the American Revolution remained unpaid. The issue persisted into the Jackson administration, poisoning relations between onetime allies.19

In all, Monroe and Adams concluded twelve commercial agreements. They managed to secure reciprocity with Britain in direct commerce, giving the United States a huge advantage in the North Atlantic carrying trade. They concluded a most-favored-nation treaty with Russia in 1824 and reciprocity agreements with several smaller European nations. On the other hand, U.S. support for the Greek revolution thwarted negotiations with Turkey. Once again, discussions with France were especially frustrating. The United States attempted to batter down France's commercial restrictions by imposing discriminatory duties, provoking a brief but bitter trade war. A limited commercial treaty negotiated in 1822 left most major issues unresolved.20

Adams and Clay entertained high hopes for trade with Latin America and invested great energy in negotiations with that region, but they achieved little. For reasons of race and politics, more than economics, southerners continued to block trade with Haiti. Raguet's provocative behavior killed a treaty with Brazil, and no treaties were negotiated with Buenos Aires, Chile, or Peru. Minister Joel Poinsett's blatant meddling in Mexican politics, as well as major differences on issues of reciprocity, limited the treaty negotiated in 1826 to most-favored-nation status. It was not ratified until much later. Clay did conclude a treaty with the Central American Federation, a political grouping of the region's five states, something he viewed as his greatest accomplishment as secretary of state and a model for a new world trading system. The federation collapsed within a short time, however, and Clay's dreams died with it.21

Most frustrating was U.S. inability to open the British West Indies. Since the Revolution, Americans had sought access to the lucrative triangular trade with Britain's island colonies. London clung stubbornly to restrictive policies. In the commercial convention of 1815, Britain limited American imports to a small number of specified goods and required that they come in British ships. With large numbers of its own vessels rotting at the docks, the United States retaliated. A Navigation Act of 1817 limited imports from the West Indies to U.S. ships. The following year, Congress closed America's ports to ships from any colony where its ships were excluded. Seeking to get at the West Indies through Canada, the United States in 1820 imposed virtual non-intercourse on Britain's North American colonies. The issue took on growing emotional significance. Americans protested British efforts to gain "ascendancy over every nation in every market of the world."22 Britons feared for their merchant marine and fretted about U.S. penetration of the empire. Even the normally conciliatory prime minister Lord Castlereagh insisted he would let the West Indies starve rather than abandon the colonial system.

Mainly because of U.S. intransigence, the conflict stalemated. Under pressure from West Indian planters and the emerging industrial class, Britain in 1822 opened a number of West Indian ports with only modest duties. Three years later, it offered to crack the door still wider if the United States would drop duties on British ships entering its ports. As secretary of state and president, Adams stubbornly persisted in trying to end the British imperial preference system, perhaps with the notion, as one of his New England constituents put it, that with full reciprocity the United States could "successfully compete with any nation on earth."23 Even the British free trader William Huskinson denounced the U.S. position as a "pretension unheard of in the commercial relations of independent states."24 When the United States refused to remove its duties, the British closed their West Indian ports. At this point, the issue became entangled in presidential politics. Jackson's supporters in Congress frustrated the administration's efforts to reopen negotiations, leaving Adams no choice but to reimpose restrictions on Britain. The Jacksonians ridiculed "Our diplomatic President," who, they claimed, had destroyed "colonial intercourse with Great Britain."25 By this time the West Indian trade had declined in practical importance, but it remained a major symbol of the clash of empires. Neither would give in.

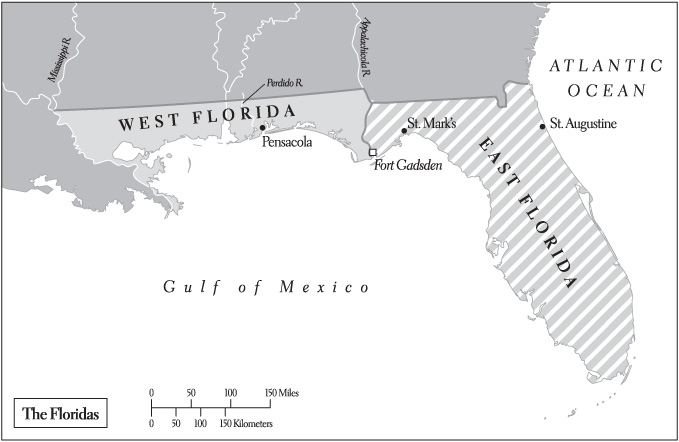

Although much stronger after the War of 1812, the United States still faced threats around its periphery. The European political situation was potentially explosive. The Latin American revolutions brought dangers as well as possible advantages. The world's greatest power remained in Canada with a long border contested at various points. Americans continued to fear British intrusion in the Pacific Northwest and Central America. The boundaries of the vast Louisiana territory were hotly disputed. For years, Spain had refused to recognize the legality of the purchase. Even after conceding on that issue, it sought to confine the United States east of the Mississippi. The United States claimed at times from the Louisiana acquisition the Floridas, Texas, and even the Oregon territory. Madison had returned East Florida to Spain in 1813. Spain's continued presence there, along with hostile Indian tribes, menaced the southern United States. In 1815, Americans still viewed the outside world with trepidation. While postponing some disputes in hopes that delay would work to their benefit, U.S. leaders continued to pursue security through expansion. In the case of Spain, Monroe and Adams enjoyed predictable success, negotiating at gunpoint a treaty securing not only the Floridas but also Spanish claims to the Pacific Northwest.

The War of 1812 underscored the importance of the Floridas, reinforced U.S. covetousness, and strengthened the nation's already advantageous position. Britain's wartime invasion of West Florida, its alliances with southwestern Indians, and its rumored plans to incite slave revolts in the southern United States all highlighted how essential it was to gain a land often likened to a pistol pointed at the nation's heart. Spain was further weakened by the Napoleonic wars. Americans believed that the long-sought territory might be detached with relative ease.26

Even when the outcome is obvious, negotiations can be difficult. The terms on which the Floridas would come to the United States were important to both nations. Spain was prepared to abandon a colony it could not defend, but it hoped to protect its territories in Texas and California against the onrushing Americans and naively counted on British support. When negotiations began in early 1818, the able Spanish minister Don Luis de Onis proposed setting the western boundary of the United States at the Mississippi River. He also sought a U.S. pledge not to recognize the new Latin American republics. Monroe and Adams insisted on a line following the Colorado River into what is now northern Texas and from there north along the 104th parallel to the Rocky Mountains. The United States was willing to delay Latin American recognition, perceiving that doing so might complicate acquisition of the Floridas or even encourage European intervention to restore monarchical governments. On the other hand, a public pledge of non-recognition would antagonize new nations with whom the United States hoped to establish a thriving commerce and anger people like Clay who sympathized with the Latin Americans. The negotiations quickly deadlocked.27

At this point, the United States began to apply not so subtle pressure against the hapless Madrid government. Under Spain's lax administration, the Floridas had become a volatile no-man's-land, a center for international intrigue and illicit commercial activities, a refuge for those fleeing oppression—and justice. The area had more than its share of pirates, renegades, and outlaws, as U.S. officials charged, but it also attracted other people, many with legitimate grievances against the United States.

Latin American rebels used Atlantic and Gulf Coast ports to stage military operations against Spanish forces. Fugitive slaves sought escape from bondage. After the 1814 Treaty of Fort Jackson, Creeks expelled from their lands fled into the Floridas, some hoping to exact retribution against the United States. Outraged when the United States purchased from the Creeks lands they claimed and then forcibly removed them, the Seminoles launched a bloody war. Conflict thus raged along the Florida border. Americans drew a picture of outlaws attacking innocent settlers. In reality, all parties contributed to the melee.28

Under intense pressure from nervous settlers in the Southwest and land speculators who feared for their investments, the Monroe administration mounted military expeditions to quell the violence that could also be used as leverage in negotiations with Spain. In December 1817, the president authorized seizure of Amelia Island from Latin American rebels whose presence threatened eventual U.S. control. Shortly after, he authorized Gen. Andrew Jackson to invade Florida and "pacify" the Seminoles.

The nature of Jackson's instructions aroused bitter controversy. In a letter to Monroe, the general indicated that if given the go-ahead he could seize Florida within sixty days. When his behavior later provoked outrage at home and abroad, he insisted that he had received this authority. Monroe adamantly denied giving Jackson such orders, leaving critics to charge that the general had acted impetuously and illegally. Although Monroe seems not to have sent the requested signal, he did give the general "full powers to conduct the war in the manner he may judge best." The president had long favored forcibly dislodging Spain from Florida. He knew Jackson well enough to predict what he might do when unleashed. Thus, although he never sent explicit instructions, he gave the general virtual carte blanche and left himself free to disavow Jackson if he went too far.29

Whatever his instructions, this "Napoleon de bois," as the Spanish called him, moved with a decisiveness that likely shocked Monroe. A lifelong Indian fighter whose code of pacification was "An eye for an eye, a toothe for a toothe, a scalp for a scalp," Jackson hated Spaniards even more than native peoples. He had long believed that U.S. security demanded that the "Wolf be struck in his den." Indeed, he preferred simply to take the Floridas.30 With a force of some three thousand regulars and state militia along with several thousand Creek allies, he plunged across the border. Unable to bring the Seminoles to battle, he destroyed their villages and seized livestock and stores of food, crippling their resistance. Claiming to act on the "immutable principle of self-defense," he occupied Spanish forts at St. Marks and Pensacola. At St. Marks, he captured a kindly Scots trader named Alexander Arbuthnot, whose principal offense was to have befriended the Seminoles, and a British soldier of fortune, Richard Armbrister, who was assisting Seminole resistance to the United States. Jackson had long believed that such troublemakers "must feel the keenness of the scalping knife which they excite." He vowed to deal with them "with the greatest rigor known to civilized Warfare."31 Accusing the two men of "wickedness, corruption, and barbarity at which the heart sickens," he tried and executed them on the spot. Arbuthnot was hanged from the yardarm of his own ship, appropriately named The Chance. The hastily assembled military court at first shied away from a death sentence for Armbrister. Jackson restored it. This trial of two British subjects before an American military court on Spanish territory was an unparalleled example of frontier justice in action. "I have destroyed the babylon of the South," Jackson excitedly wrote his wife. With reinforcements, he informed Washington, he could take St. Augustine and "I will insure you cuba in a few days."32

Jackson's escapade provoked loud outcries. Spain demanded his punishment, indemnity, and the restoration of seized property. Angry British citizens urged reprisals for the execution of Arbuthnot and Armbrister. Clay proposed that Jackson be punished for violating domestic and international law. Panicky cabinet members pressed Monroe to disavow his general.

In fact, Monroe and especially Adams skillfully exploited what Adams called the "Jackson magic" to pry a favorable treaty from Spain. Adams correctly surmised that Spanish protests were mostly bluff. To permit them to retreat with honor, Monroe agreed to return the captured forts. But the United States also demanded that Spain strike a deal quickly or risk losing everything for nothing in return. The United States also threatened to recognize the Latin American nations. In a series of powerful state papers, Adams vigorously defended Jackson's conduct on grounds that Spain's inability to maintain order compelled the United States to do so. He warned the British that if they expected their citizens to escape the fate of Arbuthnot and Armbrister they must prevent them from engaging in acts hostile to the United States. Adams's spirited defense of Jackson played fast and loose with the facts and provided a classic example, repeated often in the nation's history, of justifying an act of aggression in terms of morality, national mission, and destiny. It marked an expedient act on the part of a man known for commitment to principle. It facilitated the expansion of slavery and Indian removal, two evils Adams would spend his later life fighting.33 It also had the desired effect, breaking the back of domestic opposition, forestalling British intervention, and persuading Spain to come to terms.

The two nations reached a settlement in February 1819. Monroe abandoned his demand for Texas, perceiving that its acquisition would exacerbate an already dangerous domestic crisis over slavery in the Missouri territory. Instead, on Adams's suggestion, the United States asked for Spanish claims to the Pacific Northwest, territory also claimed by Britain and Russia. Onis at first hesitated. But in the face of U.S. adamancy and without British support, he backed down. The so-called Transcontinental Treaty left Texas in the hands of Spain but acquired for the United States unchallenged title to all of the Floridas and Spanish claims to the Pacific Northwest. The United States agreed to pay some $5 million U.S. citizens insisted they were owed by the Spanish government. The heartland of the United States was at last secure against foreign threat. A weak U.S. claim to the Pacific Northwest was greatly strengthened against a stronger British claim by acquiring Spanish interests, the most valid of the three. Even before Americans became accustomed to thinking of a republic west of the Mississippi, Adams had secured Spanish recognition of a nation extending to the Pacific and made a first move toward gaining a share of East Asian commerce.34 Taking justifiable pride in his handiwork, he hailed in his diary a "great epocha in our history" and offered "fervent gratitude to the Giver of all Good."35 He might also have thanked Andrew Jackson.

The United States also aggressively challenged British and Russian pretensions in the Pacific Northwest. Anglo-American relations improved markedly after the War of 1812. Recognizing a growing commonality of economic and political interests, the former enemies negotiated a limited trade agreement, began the difficult process of fixing a Canadian boundary, and, through the Rush-Bagot agreement of 1817 providing for reduction of armaments on the Great Lakes, averted a potentially dangerous naval arms race. The ever alert Adams also pried from Britain acceptance of the alternat, a diplomatic practice providing that the names of the two nations would be alternated when used together in the text of treaties, a symbolic achievement of no small importance.36

While moving toward rapprochement, the established imperial power and its upstart competitor also vied for preeminence in the Pacific Northwest. Many observers dismissed the mountainous Oregon country with its rocky, windblown coastline as bleak and inhospitable. Others, Adams included, saw the ports of Puget Sound and the prevalence of sea otters as keys to capturing the fabled East Asian trade. At the insistence of merchant prince John Jacob Astor, the United States after the War of 1812 reasserted claims to the mouth of the Columbia River abandoned during

the war. The aggressive Adams also sought to further U.S. interests by extending the boundary with Canada along the 49th parallel to the Pacific, a move that would have left Puget Sound, the Columbia River basin, and the Oregon country in U.S. hands. Britain would not go this far. Nor did it wish to confront the United States. In the Anglo-American Convention of 1818, the two nations agreed to leave the Oregon country open to both countries for ten years, tacitly accepting the legitimacy of U.S. claims. Persuaded that America was poised to extend its "civilization and laws to the western confines of the continent," Secretary of War and then ardent nationalist John C. Calhoun in 1817 drew up plans to locate a string of forts extending to the mouth of the Yellowstone River. Again under the guise of a scientific and literary expedition, the administration in 1819 dispatched Stephen Long to survey the Great Plains and Rocky Mountain regions. He was also to seize control of the fur trade and chip away at British influence.37

Anglo-American rivalry quickened after 1818. The Hudson's Bay Company bought out the old Northwest Company and under the watchful eye of the Royal Navy began systematically exploiting the area south of the Columbia River, hoping to discourage Americans from settling there. Astor's plans never reached fruition. Although Adams hesitated to challenge Britain directly, members of Congress such as Dr. John Floyd of Virginia and Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri increasingly warned of a British menace and urged settlement of the Oregon country. Congressional pressures were driving the United States toward a confrontation with Britain when Russia added a third side to the triangle.38

Russia's challenge in the Northwest, along with a revolution in Greece and the threat of European intervention to restore monarchical governments in Latin America, brought forth in December 1823 what came to be known as the Monroe Doctrine, one of the most significant and iconic statements of the principles of U.S. foreign policy and a ringing affirmation of U.S. preeminence in the Western Hemisphere and especially North America.39

Tsar Alexander's ukase (imperial edict) of 1821 is often viewed as a typical expression of Russia's age-old propensity for aggrandizement, but it was considerably less. On the basis of explorations, Russia claimed the Pacific coast of North America. The tsar had given the Russian-American Company a trade monopoly as far south as 55° north. The company established scattered trading posts along the Alaskan coast, but it lacked government support and faced growing U.S. competition. New England traders and poachers took most of the region's sea otters and began supplying the indigenous population with guns and whiskey. Further alarmed by talk of American settlements in the northwest, the Russian-American Company secured Alexander's assistance. Apparently without much thought, he issued on September 4, 1821, another ukase granting Russians exclusive rights for trading, whaling, and fishing in the area of Alaska and the Bering Sea and south along the coast to 51° (far south of Russia's main settlement near the present site of Sitka, Alaska). Under threat of confiscation and capture, the ukase also forbade foreign ships from approaching within 100 Italian miles (115 English miles) of Russian claims.40

The ukase aroused grave concern in the United States. Russia's territorial aspirations posed no direct threat, since the United States had never claimed above 49°. The hostile reaction reflected more U.S. pretensions than those of Russia. But the coastal restrictions challenged the principle of freedom of the seas and threatened one of the most profitable enterprises of Adams's New England constituents. Congressmen agitated for settlement of the Columbia basin and urged Monroe to defend U.S. interests. The tsar at precisely this time was arbitrating an Anglo-American dispute over slaves carried away during the War of 1812, so Monroe and Adams proceeded cautiously. At the first opportunity, however, Adams informed the Russian minister "that we should contest the right of Russia to any territorial establishment on this continent, and that we should assume distinctly the principle that the American continents are no longer subjects for any new colonial establishments."41

The outbreak of revolution in Greece posed the equally significant and not entirely unrelated issue of America's commitment to republican principles and the role it should play in supporting liberation movements abroad. In the spring of 1821, the Greeks revolted against Turkish rule. Early the following year, various resistance groups coalesced, issued an American-style declaration of independence, and appealed to the world—and especially the "fellow-citizens of Penn, of Washington, and of Franklin"—for assistance.

Widely acknowledged as the birthplace of modern democracy, Greece became the cause célèbre of the era. "Greek fever" took hold in the United States. Americans viewed the revolution as an offspring of their own and the Turks as the worst form of barbarians and infidels. Pro-Greek rallies were staged in numerous towns and cities; speakers called for contributions and volunteers. In one of the most famous exhortations, Harvard professor Edward Everett enjoined Americans to fulfill "the great and glorious part which this country is to act, in the political regeneration of the world."42

The issue divided the U.S. government. Always the skeptic, Adams dismissed the Greek infatuation as "all sentiment" and feared that support for the rebels would jeopardize trade negotiations with Turkey. On the other hand, minister to France Gallatin urged employment of the U.S. Navy's Mediterranean squadron against the Turks. Former president Madison advocated a public declaration in favor of Greek independence. Congressmen Clay and Daniel Webster of Massachusetts used their famed eloquence to press for the dispatch of an official agent to Greece. Clay indignantly protested that U.S. support for liberty was being compromised by a "miserable invoice of figs and opium." Monroe was leaning toward recognition when a more pressing challenge led the administration to take a public stand on the several issues it confronted.43

The possibility of European intervention to suppress the Latin American revolutions was the most serious threat to face the United States since the War of 1812. Following the Napoleonic wars, Tsar Alexander had taken the lead in mobilizing the Continental powers to check the forces of revolution. A religious fanatic whose propensity for prayer was said to have caused calluses on his knees, Alexander later became obsessed with a fear of revolution and increasingly associated opposition with godliness. For reasons of state, he refused to help the Turks suppress the Greeks. At the Congress of Verona in November 1822, however, he secured an allied commitment to restore the fallen monarchy in Spain. French troops subsequently accomplished this mission. With the Spanish monarchy restored, talk swept Europe of an allied move to restore Spain's Latin American colonies or establish in Latin America independent monarchies.44

The United States had responded cautiously to the Latin American revolutions. Adams was delighted with the further dissolution of European colonialism and hoped eventually to secure trade advantages from an independent Latin America. At the same time, he believed that the Spanish and Catholic influence was too strong to permit the growth of republicanism among the new nations. He did not share the enthusiasm of Clay and others who foresaw a group of Latin American nations that were closely tied to the United States and that might build institutions resembling those of the North Americans. Nor did he wish to antagonize Spain as long as the Florida question was unresolved and the threat of recognition gave him leverage with Onis. Over the protests of Clay and others, the administration withheld recognition until 1822 and sought to implement an "impartial neutrality." Clay's position was popular, however, and clandestine organizations in East Coast ports provided arms, supplies, and mercenaries for the rebels. Loopholes in the neutrality laws permitted the fitting-out in U.S. ports of privateers that preyed on Spanish shipping.45

Whatever its attitudes toward Latin America, the United States could only view with alarm the possibility of European intervention. The threat revived memories of those early years when the omnipresent reality of foreign intrusion endangered the very survival of the new republic. It could foreclose commercial opportunities that now seemed open in the hemisphere.

Curiously, in light of past antagonisms, it was the old Yankeephobe British foreign secretary George Canning who brought the issue of European intervention to the forefront. During conversations with a shocked U.S. minister Richard Rush in the summer of 1823, Canning proposed a joint statement opposing European intervention to restore the Spanish colonies and disavowing American and British designs on the new nations. The motives for this quite extraordinary proposal remain a matter of speculation. Canning may already have committed himself to recognition of the Latin American nations and was seeking U.S. support against critics at home and abroad. Many Americans, Adams included, suspected a clever British trick to keep Cuba out of U.S. hands.46

Whatever the case, Canning's "great flirtation" set off a prolonged debate in Washington. As was his custom, Monroe consulted with his illustrious Virginia predecessors before going to his cabinet. Jefferson and Madison swallowed their Anglophobia and counseled going along with Canning. Persuaded that European intervention was likely if not certain, Calhoun agreed.47 Adams disagreed, and on most issues he prevailed. He astutely and correctly minimized the likelihood of European intervention. As secretary of state and a presidential aspirant, he may have feared that joining with Britain would leave him vulnerable to charges of being too cozy with an old enemy.48 He was also alert to the advantages of acting alone. Acceptance of Canning's proposal might for the short run jeopardize chances of getting Cuba or Texas. An independent stance might advance prospects of trade with Latin American nations. "It would be more candid, as well as more dignified," he advised the cabinet, "to avow our principles explicitly to Russia and France than to come in as a cockboat in the wake of the British man-of-war."49 Reaffirming his long-held view that U.S. political interests lay primarily on the North American continent and warning against an unnecessary affront to the European powers, Adams talked Monroe out of recognizing Greece. The president overruled his secretary of state only on the form the statement should take, including it in his annual message to Congress rather than the diplomatic dispatches Adams would have preferred (as that would have given him more credit).

What much later came to be called the Monroe Doctrine, in whose formulation Adams played the crucial role, was contained in separate parts of the president's December 2, 1823, message to Congress. Asserting the doctrine of the two spheres, which had some precedent in European treaties, he sharply distinguished between the political systems of the Old World and the New and affirmed that the two should not impinge on each other. He went on to enunciate a "non-colonization principle," a bold and pretentious public reiteration of the position Adams had taken privately with the Russian and British ministers: The American continents "by the free and independent conditions which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects of colonizations by any European power." Monroe went on to affirm that generally, and in the specific case of Greece, the United States would not interfere in the "internal affairs" of Europe. On the most pressing issue, he set forth a non-intervention principle, warning the Holy Allies and France that the United States would regard as "dangerous" to its "peace and safety" any European effort to "extend their system to any portion of the hemisphere."50

Monroe's statement raised as many questions as it answered. It left unclear whether the non-colonization principle applied with equal weight to all of North and South America and what—if anything—the United States might do to defend the independence of Latin America. The Greek issue was settled when Congress subsequently tabled a resolution calling for recognition, but Monroe's statement did not close the door entirely to U.S. involvement in Europe. It did not even represent a definitive exposition of U.S. policy. The administration, Adams included, was prepared to consider an Anglo-American alliance should the threat of European intervention materialize.51

The immediate response gave little indication that Monroe's pronunciations would assume the status of holy writ. Americans lustily cheered and then largely forgot the ringing reaffirmation of America's independence from Europe. European reaction ranged from outright hostility to incredulity at the pretentiousness of such strong words from such a weak nation. That high priest of the old order, Austria's Prince Metternich, privately denounced the statement as a "new act of revolt" and warned that it would "set altar against altar" and give "new strength to the apostles of sedition and reanimate the courage of every conspirator."52 When Canning realized that he had been outmaneuvered, he released a statement given him by the French government making clear that Britain had been responsible for deterring European intervention. Many Latin Americans had minimized the threat of European intervention from the outset. Those who took it seriously perceived that Britain, not the United States, had headed it off. Latin American leaders were eager to ascertain whether Monroe's apparent offer of support had substance, but they also feared a North American threat to their independence. The practical effects of the "doctrine" were also limited. Indeed, for many years, the United States stood by while Britain violated—and enforced—its key provisions

The Monroe "doctrine" was by no means a hollow statement. It neatly encapsulated and gave public expression to goals Monroe and Adams had pursued aggressively since 1817. That it was issued at all reflected America's ambitions in the Pacific Northwest and its renewed concerns for its security. That it was done separately from Britain reflected the nation's keen interest in acquiring Texas and Cuba and its commercial aspirations in Latin America. It expressed the spirit of the age and provided a ringing, if still premature, statement of U.S. preeminence in the hemisphere. It publicly reaffirmed the continental vision Adams had already privately shared with the British and Russians: "Keep what is yours but leave the rest of the continent to us."

Monroe, Adams, and Clay continued to pursue this vision, pushing relentlessly against foreign positions in the Northwest and Southwest. Adams's vigorous protests against the ukase and Monroe's message were heard in St. Petersburg. This time listening to his foreign policy advisers rather than the Russian-American Company, the tsar made major concessions in treaties of 1824 and 1825, dividing Russian and United States "possessions" at 54° 40', opening the ports and coasts of the Russian Pacific to U.S. ships, and leaving the unsettled stretches of the Pacific Northwest open to American traders as long as they did not sell firearms and whiskey to the indigenous peoples.53

Chosen president by the House of Representatives after a hotly disputed 1824 election, Adams immediately ratcheted up the pressure on Britain. He sent the veteran diplomat Gallatin to London with instructions to extend the boundary along the 49th parallel to the Pacific. Still determined to protect British interests in the Oregon country, Canning insisted on the Columbia River as a boundary. When it was evident that neither nation would back down, they agreed in 1827 to leave the territory open indefinitely to the citizens of each. Adams found it expedient to delay rather than risk conflict at a time when the U.S. position was still weak.

The United States also tried to roll back Mexico's boundaries in the Southwest. Clay had bitterly attacked Monroe and Adams for abandoning Texas in 1819. As Adams's secretary of state, he lamented that the Texas border "approached our great western Mart [New Orleans], nearer than could be wished."54 With the president's blessings, he pushed the newly independent and still fragile government of Mexico to part with territory into which large numbers of U.S. citizens were already flocking. He authorized his minister to Mexico, South Carolinian Joel Poinsett, to negotiate a boundary at the Brazos River or even the Rio Grande, arguing, with transparently self-serving logic, that the detachment of Texas would leave the capital, Mexico City, closer to the nation's center, making it easier to administer. Not surprisingly, Mexico rejected Poinsett's overtures and Clay's logic. An outspoken champion of U.S.-style republicanism, the ebullient diplomat (better known for giving his name to a brightly colored Christmas flower native to Central America) was instructed by Clay to represent to Mexicans the "very great advantages" of the (North) American system. Poinsett took his instructions much too seriously, openly expressing his disdain for Mexican institutions and aligning himself with the political opposition. The triumph of the group he backed changed nothing. The new government resisted the meddlesome minister's offers of $1 million for the Rio Grande boundary and in 1829 requested his recall. As with Britain in the Northwest, Adams and Clay refused to press the matter, certain that in time Texas would fall into U.S. hands.55

Implicit in the Monroe Doctrine was a commitment to the extension of the ideology and institutions of the United States, a key issue throughout much of the mid-1820s. The Greek and Latin American revolutions made it a practical and tangible matter. The marquis de Lafayette had dedicated his life to liberal causes. His triumphal pilgrimage across the United States in 1825 evoked an orgy of speeches and celebrations, reminding Americans of the glories of their revolution and stimulating sympathy for the cause of liberty elsewhere. The fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1826, also brought forth talk of a rededication to freedom. The remarkable, coincidental deaths of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams on that very day seemed to President John Quincy Adams a "visible and palpable" sign of "Divine favor," a reminder of America's special role in the world.56

Much of the initiative for the extension of American ideals came from individuals, and the impetus was mainly religious. Inspired by the American Revolution and by a revival that swept the nation in the 1820s (the Second Great Awakening), troubled by the rampant materialism that accompanied frenzied economic growth, a small group of New England missionaries set out to evangelize the world. Originating primarily in the seaport communities and often backed by leading merchants, they saw religion, patriotism, and commerce working hand in hand. They were committed to the view of Congregationalist minister Samuel Hopkins that the spread of Christianity would bring about "the most happy state of public society that can be enjoyed on earth."57 In the beginning, American evangelicals worked with the British. The first missionary traveled to India in 1812. In the 1820s, they struck out on their own. They did not seek or expect government support. Certain that the millennium was at hand—the estimated date was 1866—they brought to their work a special urgency and believed the task could be done in a generation. A mission went to Latin America in 1823 to survey the prospects of liberating that continent from Catholicism and monarchy. "If one part of this new national family should fall back under a monarchical system, the event must threaten, if not bring down evils, on the part remaining."58 Two African American Baptist ministers were among the first Americans to go to Africa. The major thrust was the Middle East. An intrepid group of missionaries left for Jerusalem in 1819 to liberate the birthplace of Christianity from "nominal" Christians, "Islamic fanaticism," and "Catholic superstition." Plunged into the deadly maelstrom of Middle Eastern religion and politics, the mission moved on to Beirut and barely survived. But it established the foundation for a worldwide movement that would play an important role in U.S. foreign relations before the end of the century.59

The concept of mission assumed a major place in the foreign policy of Adams and Clay. The zealous, romantic Kentuckian had always championed the cause of freedom, often to the discomfiture of Monroe and Adams. As secretary of state, Adams had rebuffed Clay's proposals to support the Greek and Latin American revolutions—the United States should be the "well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all . . . , the champion and vindicator only of her own," he proclaimed in an oft-quoted July 4, 1821, oration responding to Clay.60 But as president he moved in that direction. Shortly after Lafayette's visit, he dispatched a secret agent to offer U.S. sympathy to the Greeks and assess their ability to "sustain an independent Government." Whether Adams saw this as preliminary to recognition is unclear. It became irrelevant. The agent died en route. In April 1826, the Greeks suffered a crushing defeat, seemingly answering the question he was sent to ask. Adams nonetheless expressed sympathy for them in subsequent speeches. He hailed the outbreak of war between Russia and Turkey in 1828 as offering them renewed hope.61

Closer to home, Adams and Clay sought to encourage republicanism in Latin America. For years, Clay had ardently championed Latin American independence. As secretary of state, he aspired to commit hemispheric nations to a loose association based on U.S. political and commercial principles. Although skeptical, Adams too came to envision the United States providing leadership to the hemisphere in those "very fundamental maxims which we from our cradle at first proclaimed and partially succeeded to introduce into the code of national law." The two men feared that the Latin American republics might fall back under European sway or as independent nations compete with each other and the United States in ways that threatened U.S. interests. The best solution seemed to be to reshape them according to North American republican principles and institutions.62

There is a fine line between encouraging change in countries and interfering in their internal affairs, and Adams, Clay, and their diplomats often crossed it. Raguet publicly expressed contempt for Brazil's monarchy and the corruption and immorality that, he claimed, inevitably accompanied it. Poinsett used the Freemasons' organization to foment opposition to the government of Mexico. The U.S. chargé actively intruded in a debate among Chileans over the principles of government.63 During the revolutions against Spain, North Americans hailed Simón Bolívar as the George Washington of Latin America. But his advocacy of a presidency for life for Bolivia and Colombia aroused suspicions of British influence and fears of a turn toward monarchy. Clay privately enjoined the Liberator to choose the "true glory of our immortal Washington, to the ignoble fame of the destroyers of liberty." The U.S. chargé in Peru denounced Bolívar as a usurper and "madman" and backed his opponents. Minister to Colombia William Henry Harrison openly consorted with Bolívar's enemies and was asked to leave. An admirer of the United States, the Liberator observed that this rich and powerful northern neighbor "seemed destined by Providence to plague America with torments in the name of freedom."64

Adams and Clay never permitted the cause of freedom to interfere with more important interests. They were willing to recognize the Brazilian monarchy as long as Brazil's ports were open to U.S. trade. When the threat of European intervention caused Latin American leaders to ask how the United States might respond, they got only vague responses. Monroe's statement had not conveyed "any pledge or obligation the performance of which foreign nations have a right to demand," Clay asserted. The United States flatly rejected proposals by Colombia and Brazil for alliances. When wars or rumors of war among the Latin nations themselves threatened Hemispheric stability, Clay and Adams stuck to a policy of "strict and impartial neutrality."65

With Haiti and Cuba, race, commerce, and expediency dictated support for the status quo. Clay was inclined to recognize Haiti, but southerners like Calhoun fretted about "social relations" with a black diplomat and the participation of his children "in the society of our daughters and sons." Adams opposed recognition as long as the black republic granted exclusive trade privileges to France and showed "little respect" for "races other than African."66 The United States preferred the certainties of continued Spanish control of Cuba to the risks of independence. Its rule threatened throughout the 1820s by rebellion from within and a possible British takeover or Mexican or Colombian invasion from without, Spain maintained at best a precarious hold on its island colony. United States officials, on the other hand, saw Cuba as a natural appendage of their country, certain, as Adams put it, that, like an "apple severed by the tempest from its native tree," Cuba, once separated from Spain, could "gravitate only towards the North American union." For the moment, they were content with the status quo. A premature move to acquire Cuba might provoke British intervention. The "moral condition, and discordant character" of Cuba's predominantly black population raised the specter of the "most shocking excess" of the Haitian revolution. Clay and Adams thus rebuffed schemes proposed by Cuban planters for U.S. annexation and rejected British proposals for a multilateral pledge of self-denial. They warned off Mexico and Colombia, proclaiming that if Cuba was to become a dependency of any nation "it is impossible not to allow that the law of its position proclaims that it should be attached to the United States." They did nothing to encourage Cuban independence, preferring the status quo as long as the island was open to U.S. trade.67

Adams and Clay's efforts to promote closer relations with hemispheric neighbors through participation in an inter-American conference in Panama became hopelessly entangled in the bitter partisan politics that afflicted their last years in office. Bolívar conceived the idea of an inter-American congress to build closer ties among the new nations to help fend off European intervention and perhaps also support his own ambitions for Hemispheric leadership. Some Latin American leaders saw inviting the United States as a means to secure the pledges of support Washington had been unwilling to give on a bilateral basis. Adams and Clay were not prepared to go this far, but they were willing to participate, Clay to further his dreams of an American System, Adams, who critics sneered had caught the "Spanish American fever" from his secretary of state, to promote U.S. commerce and demonstrate goodwill. Their missionary impulse was manifest in Clay's instructions to the delegates. They were not to proselytize actively, but they should be ready to respond to questions about the U.S. system of government and the "manifold blessings" enjoyed by the people under it.68

The Panama Congress became a political lightning rod, drawing increasingly bitter attacks from the followers of presidential aspirants former secretary of the treasury William Crawford, Vice President Calhoun, and especially Andrew Jackson. Critics ominously warned that participation would violate Washington's strictures against alliances and sell out U.S. freedom of action to a "stupendous Confederacy, in which the United States have but a single vote." Southerners protested association with nations whose economies were competitive, expressed concern that the congress might seek to abolish slavery, and objected to association with Haitian diplomats. A Georgia senator issued dire warnings against meeting with "the emancipated slave, his hands yet reeking in the blood of his masters." The acerbic Virginia congressman John Randolph of Roanoke declaimed against a "Kentucky cuckoo's egg, laid in a Spanish-American nest." Condemning the political "bargain" that had allegedly given Adams the presidency and made Clay secretary of state, he sneered at the union of the "Puritan with the black-leg," a "coalition of Blifil and Black George" (the reference to especially unsavory characters from Henry Fielding's novel Tom Jones). Randolph's charges provoked a duel with Clay more comical than life-threatening, the only casualty of which was the Virginian's greatcoat.69

United States participation never materialized. A hostile Senate delayed for months voting on Adams' nominees. By the time they were finally approved, one refused to go to Panama during the "sickly season," and the other died before receiving his instructions. When the congress finally assembled in June 1826 after repeated delays, no U.S. representative was present. After a series of sessions, it adjourned with no plans to reconvene. Adams gamely persisted, appointing a new representative, but the congress never met formally again. The Senate refused even to publish the administration's instructions to its delegates, writing a fitting epitaph to a comedy of errors. For the first time but by no means the last, a major foreign policy initiative fell victim to partisan politics.70

The Panama Congress fiasco typified the travails of Adams's presidency. Perhaps the nation's most successful secretary of state, he met frustration and failure in its highest office.71 Although he brought to the White House the most limited mandate, he set ambitious goals. He and Clay achieved some important accomplishments, especially in the construction of roads and canals and the passage of a highly controversial protective tariff in 1828. In most areas, they failed. Outraged at losing an election in which they had won a plurality of the popular vote, Jackson and his supporters built a vibrant political organization and obstructed administration initiatives. Caught off guard by the opposition, Adams often seemed incapable of asserting effective leadership. Perhaps like Jefferson and also from hubris, he too overreached, refusing to bend from principle in trade negotiations with England and badly misjudging the willingness of weak nations such as Mexico to succumb to U.S. pressure.

This said, the era of Monroe and Adams was rich in foreign policy accomplishment. Through the Transcontinental Treaty, the United States secured its southern border, gained uncontested control of the Mississippi, and established a foothold in the Pacific Northwest. The threat of European intervention diminished appreciably. Britain was still the major power in the Western Hemisphere, but the United States in a relatively short time emerged as a formidable rival, already larger than all the European states except for Russia. Still threatened by manifold dangers in 1817, the U.S. continental empire was firmly established by 1824. Well might Adams observe in his last months as secretary of state that never had there been "a period of more tranquility at home and abroad since our existence as a nation than that which prevails now."72

The election of Andrew Jackson in 1828 provoked alarm among some Americans and many Europeans, especially in the realm of foreign policy. The first westerner to capture the White House, Jackson, unlike his predecessors, had not served abroad or as secretary of state. His record as a soldier, especially in the invasion of Florida, raised legitimate concerns that he would be impulsive, even reckless, in the exercise of power.

Jackson introduced important institutional changes. His cabinet met sparingly and rarely discussed foreign policy. He went through four secretaries of state in eight years, much of the time assuming for himself the primary role in policymaking. He instituted the first major reform of the State Department, creating eight bureaus and elevating the chief clerk to a status roughly equivalent to a modern undersecretary. He expanded the consular service and sought to reform it by paying salaries, thus reducing the likelihood of corruption, only to have a penurious Congress reject his proposal and try to reduce U.S. representation abroad. With much fanfare, he institutionalized the principle of rotation in office—a spoils system, critics called it. He used the diplomatic service for political ends. Ministers William Cabell Rives, Louis McLane, Martin Van Buren, and James Buchanan distinguished themselves in European capitals, but they were among the major exceptions to a generally weak group of diplomatic appointments. The eccentric John Randolph—sent to St. Peters-burg to get him out of Washington—left after twenty-nine days, finding the Russian weather unbearably cold even in August. Jackson crony and world-class scoundrel Anthony Butler was the worst of a sorry lot of appointments to Latin America.73

In keeping with the democratic spirit of the day, Jackson altered the dress of the diplomatic corps. His Democratic Party followers accused Monroe and Adams of trying to "ape the splendors . . . of the monarchical governments"; Jackson himself thought the fancy diplomatic uniform "extremely ostentatious" and too expensive. He introduced an outfit more in keeping with "pure republican principles," a plain black coat with gold stars on the collar and a three-cornered hat.74

Jackson's changes were more of style and method than substance. Cadaverous in appearance with strikingly gray hair that stood on end, chronically ill, still bearing the scars from numerous military campaigns and carrying in his body two bullets from duels, the rough-hewn but surprisingly sophisticated hero of New Orleans embodied the spirit of the new republic. His rhetoric harked back to the republican virtues of a simpler time, but he was both the product and an ardent promoter of an emerging capitalist society. Domestic struggles such as the nullification controversy and the bank war occupied center stage during Jackson's presidency. There were no major foreign policy crises. At the same time, Jackson saw foreign policy as essential to domestic well-being and gave it high priority. He was less concerned with promoting republicanism abroad than with commanding respect for the United States. He readily embraced the global destiny of a rising nation. More than his predecessors, he sought to project U.S. power into distant areas. He energetically pursued the major goals set by Monroe, Adams, and the despised Clay: to expand and protect the commerce upon which America's prosperity depended; to eliminate or at least roll back alien settlements that threatened its security or blocked its expansion.75

Jackson's methods represented a combination of frontier bluster and frontier practicality. In his first inaugural, he vowed to "ask nothing but what is right, permit nothing that is wrong." He did not live up to this high standard, but he did establish a style distinctly his own. Like Monroe and Adams, he had been profoundly influenced by the menacing and sometimes humiliating experiences of the republic's infancy. He was extremely sensitive to insults to the national honor and threats to national security. He claimed to stand on principle. He insisted that other nations be made to "sorely feel" the consequences of their actions; he was quick to threaten or use force if he thought his nation wronged. In actual negotiations, however, he was conciliatory and flexible. If, on occasion, he raised relatively minor issues to the level of crises, he also solved by compromise problems that had frustrated Adams, a man renowned for diplomatic skill. His gracious manner and folksy charm won over foreigners who expected to find him offensive.76

Like Monroe and Adams before him, Jackson gave high priority to expanding U.S. trade. A product of the southwestern frontier, he recognized the essentiality of markets for American exports. Despite the efforts of his predecessors, commerce had stagnated in the 1820s, and surpluses of cotton, tobacco, grain, and fish threatened the continued expansion of agriculture, commerce, and manufacturing. He thus moved vigorously to resolve unsettled claims disputes, break down old trade barriers, and open new markets.77

Jackson perceived that securing payments of outstanding claims would bind grateful merchants to him, stimulate the economy, and facilitate new trade agreements. Through patient negotiation and the timely deployment of naval power, he extracted $2 million from the Kingdom of Naples. The threat of a trade war helped secure $650,000 from Denmark. Settlement of the long-standing French claims dispute represented a major success of his first administration and reveals much about his methods of operation. He attached great importance to the negotiations, believing that other nations would view failure as a sign of weakness. Informed by minister Rives that France would not pay unless "made to believe that their interests . . . require it," Jackson took a firm position. But after months of laborious negotiations, when the fragile new government of Louis Philippe offered to settle for $5 million, he readily assented, conceding that, although less than U.S. demands, the sum was fair. The United States promised to pay 1,500,000 francs to satisfy French claims from the American Revolution.78

Jackson almost undid his success by pressing too hard for payment. Without bothering to determine when the first installment was due or notify the French government, he ordered a draft on the French treasury. It was returned unpaid, and the Chamber of Deputies subsequently rejected appropriations for the settlement. At this point, an angry Jackson impulsively threatened to seize French property. "I know them French," he reportedly exclaimed. "They won't pay unless they are made to."79 The Chamber appropriated the funds but refused to pay until Jackson apologized. The dispute quickly escalated. The French recalled their minister from Washington, asked Rives to leave Paris, and sent naval forces to the West Indies. Jackson drafted a bellicose message and ordered the navy to prepare for war. A totally unnecessary conflict over a relatively trivial sum was averted when a suddenly conciliatory Jackson in his December 1835 message to Congress refused to apologize but insisted he meant no offense. Paris viewed the apology that was not an apology as sufficient and paid the claims.80

Jackson also broke the long-standing and often bitter deadlock over access to the British West Indies. The departure of Adams and the death of Canning in 1827 greatly facilitated settlement of an apparently intractable issue. More interested in markets than shipping, Jackson's southern and western constituents exploited Adams's blunders in the 1828 campaign. To prove his mettle as a diplomat, Jackson sought to succeed where his predecessor had failed. British planters and industrialists had long pressed the government to resolve the issue. At least for the moment, instability on the Continent made good relations with the United States especially important.81

The two nations thus inched toward resolving an issue that had vexed relations since the American Revolution. Persuaded that Adams's rigidity had frustrated earlier negotiations, Jackson abandoned his predecessor's insistence that Britain give up imperial preference. He continued to talk tough, at one point threatening to cut off trade with "Canady." But when advised by McLane in 1830 that the issue might be settled more easily by action than negotiation, he removed the retaliatory measures prohibiting entry into U.S. ports of ships from the British West Indies. London responded by opening the West Indies to direct trade. An issue that had grown in symbolic importance while declining in practical significance was at last settled, removing a major impediment to amicable relations. Britons especially had feared accession of the allegedly Anglophobic Jackson, executioner of Arbuthnot and Armbrister. His demeanor in these negotiations won him an esteem in London given none of his predecessors and evoked a determination, in the words of King William IV, to "keep well with the United States."82

Jackson also energetically pursued new trade agreements. James Buchanan's dismal later performance as president has obscured his considerable skill as minister to Russia. He endured the St. Petersburg weather and the constant surveillance placed on foreigners. He ingratiated himself at court through his storytelling and dancing, even his flattery of the tsar. He negotiated a treaty providing for reciprocity in direct trade and access to the Black Sea.83

The United States also managed to achieve the treaty with Turkey that had eluded it for thirty years. Destruction of the Turkish navy by a combined European fleet at Navarino in 1827 convinced the sultan that closer relations with the United States would be useful. In return for a "separate and secret" U.S. promise to assist in rebuilding its navy, Turkey agreed to establish diplomatic and consular relations, trade on a most-favored-nation basis and admit American ships to the Black Sea. Although the Senate rejected the secret article, Americans without official sanction helped design ships and train sailors for the Turkish navy. The commercial treaty did not live up to expectations, only the exchange of rum and cotton goods in Smyrna for opium, fruit, and nuts turning out to be significant, but it established, along with the missionaries in Beirut, a basis for U.S. involvement in the Middle East.84

Jackson eagerly sought out trade with Asia. In January 1832, he appointed New England merchant and veteran sailor Edmund Roberts as a special agent to negotiate treaties with Muscat, Siam (Thailand), and Cochin China (southern Vietnam). To keep his mission secret, Roberts was given "ostensible employment" as clerk to the commander of the sloop Peacock. This first encounter between the United States and Vietnam was not a happy one. The ship landed near present-day Qui Nhon in January 1833. The discussions that followed constituted a classic cross-cultural exercise in futility. Low-level Vietnamese officials raised what Roberts called "impertinent queries," namely, whether the visitors had brought the obligatory presents for the king. Himself an imperious figure and like most Americans of the time strongly nationalistic, Roberts staunchly refused to use the "servile forms of address" the Vietnamese demanded in dealing with the emperor. They would accept nothing less, insisting that since the U.S. president was elected he was obviously inferior to a king. Roberts took a strong dislike to his hosts, describing them as untrustworthy and "without exception the most filthy people in the world." Most important, he refused to submit to "any species of degradation"—notably the elaborate ritual known as the ko-tow—to "gain commercial advantage." After a month of unproductive discussions, the Peacock sailed away.

Roberts's frustrations with Vietnam persisted. The Peacock went on to insular Southeast Asia, where he negotiated treaties with the rulers of Siam and Muscat, the former a model of commercial liberality. Jackson was so pleased that he asked his envoy to go back to Cochin China and then proceed to Japan, pragmatically imploring him, this time, to conform to local custom "however absurd." Wined and dined by rulers across the world, the venturesome Roberts had survived shipwrecks, pirates, and disease. This time his luck ran out. He contracted cholera en route. His ship landed at Da Nang in May 1836, but after a week of futile discussions, this time hampered by his illness, he sailed to Macao, where he died before completing his mission. The emperor Ming-Mang summed up the experience with a poem: