The great transformation in U.S. foreign relations that began in the Gilded Age culminated in the 1890s. During that tumultuous decade, the pace of diplomatic activity quickened. Americans took greater notice of events abroad and more vigorously asserted themselves in defense of perceived interests. The war with Spain in 1898 and the acquisition of overseas colonies have often been viewed as accidents of history, departures from tradition, "the great aberration," in historian Samuel Flagg Bemis's words, "empire by default," according to a more recent writer.1 In fact, the United States in going to war with Spain acted much more purposefully than such interpretations allow. To be sure, the nation broke precedent by acquiring overseas colonies with no intention of admitting them as states. At the same time, in its aims, its methods, and the rhetoric used to justify it, the expansionism of the 1890s followed logically from earlier patterns, built on established precedents, and gave structure to the blueprint drawn up by James G. Blaine in the previous decade.

During the 1890s, Americans became acutely conscious of their emerging power. "We are sixty-five million of people, the most advanced and powerful on earth," a senator observed in 1893 with pride and more than a touch of exaggeration.2 "We are a Nation—with the biggest kind of N," Kentucky journalist Henry Watterson added, "a great imperial Republic destined to exercise a controlling influence upon the actions of mankind and to affect the future of the world."3

Acknowledgment of this new position came in various forms. In 1892, the Europeans upgraded their ministers in Washington to the rank of ambassador, tacitly recognizing America's status as a major power.4 One year later, Congress without debate scrapped its republican inhibitions and the practices of a century by creating that rank within the U.S. foreign service, a move of more than symbolic importance. United States diplomats had long bristled at the lack of precedence accorded them in foreign courts because of their lowly rank of minister. They viewed the snubs and shabby treatment as an affront to the prestige of a rising power. An ambassador also had better access to sovereigns and prime ministers, it was argued, and could therefore negotiate more easily and effectively.5

The Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 both symbolized and celebrated the nation's coming of age. Organized to commemorate the four-hundredth anniversary of Columbus's "discovery" of America, it was used by U.S. officials to promote trade with Latin America.6 Its futuristic exhibits took a peek at life in the twentieth century. It displayed high culture and low, the latter including Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, the first Ferris wheel, and the exotic performances of belly-dancer Little Egypt. It highlighted American technology and the mass culture that would be the nation's major export in the next century. Above all, it was a patriotic celebration of U.S. achievements, past, present, and to come. Frenchman Paul de Bourget was "struck dumb . . . with wonderment" by what he saw, "this wonderfully new country" in "advance of the age."7

Wonder and pride were increasingly tempered by fear and foreboding. During the 1890s, Americans experienced internal shocks and perceived external threats that caused profound anxieties and spurred them to intensified diplomatic activity, greater assertiveness, and overseas expansion. Ironically, just a month after the opening of the Columbian Exposition, the most severe economic crisis in its history stunned the nation. Triggered by the failure of a British banking house, the Panic of 1893 wreaked devastation across the land, causing some fifteen thousand business failures in that year alone and 17 percent unemployment. The depression shook the nation to its core, eroding optimism and raising serious doubts about the new industrial system.8

Social and political concerns combined with a malfunctioning economy to produce confusion about the present and anxiety for the future.9 Close to a half million immigrants arrived in the United States each year in the 1880s. The ethnic makeup of these newcomers—Italians, Poles, Greeks, Jews, Hungarians—was even more unsettling to old-stock Americans than their numbers, threatening a homogenous social order. The sprawling, ugly cities they populated produced fears for the survival of a simpler, agrarian America.

Democracy itself seemed in jeopardy. At first enthusiastically hailed for their productive capacity, giant corporations such as Standard Oil, Carnegie Steel, and the Pennsylvania Railroad, and the huge banking houses such as J. P. Morgan and Co. that financed them, became increasingly suspect because of the allegedly corrupt and exploitative practices used by the so-called robber barons to build them, the enormous power they wielded, and their threat to individual enterprise. At the Chicago exposition, historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented a paper attributing American democracy to the availability of a western frontier. Coming at a time when demographers were claiming (incorrectly, as it turned out) that the continental frontier had closed, Turner's writings aroused concerns that the nation's fundamental values were in jeopardy. Such fears produced a "social malaise" that gripped the United States through much of the decade.10

The crisis was evidenced in various ways. The growing militancy of labor—there were 1,400 strikes in the year 1894 alone—and the use of force to suppress it produced a threat to social order that frightened solid middle-class citizens. The violence that accompanied the 1892 Homestead "massacre" in Pennsylvania, where private security forces battled workers, and the Pullman strike in Illinois two yeas later in which thirteen strikers were killed was particularly unsettling. The march on Washington of Jacob Coxey's "army" of unemployed in the spring of 1894 to demand federal relief and the Populist "revolt" of embattled southern and western farmers proposing major political and economic reforms portended a radical upheaval that might alter basic institutions.

The nation also appeared threatened from abroad. The uneasy equilibrium that had prevailed in Europe since Waterloo seemed increasingly endangered. The worldwide imperialist surge quickened in the 1890s. The partition of Africa neared completion. Following Japan's defeat of China in their 1894–95 war, the European powers turned to East Asia, joining their Asian newcomer in marking out spheres of influence, threatening to eliminate what remained of the helpless Middle Kingdom's sovereignty, perhaps shutting it off to American trade. Some Europeans spoke of closing ranks against a rising U.S. commercial menace. Some nations raised tariffs. Britain's threat to impose imperial preference in its vast colonial holdings portended a further shrinkage of markets deemed more essential than ever in years of depression.11

The gloom and anxiety of the 1890s produced a mood conducive to war and expansion. They triggered a noisy nationalism and spread-eagle patriotism, manifested in the stirring marches of John Philip Sousa and outwardly emotional displays of reverence for the flag. The word jingoism was coined in Britain in the 1870s. Xenophobia flourished in the United States in the 1890s in nativist attacks upon immigrants at home and verbal blasts against nations that affronted U.S. honor. For some Americans, a belligerent foreign policy offered a release for pent-up aggressions and diversion from domestic difficulties. It could "knock on the head . . . the matters which have embarrassed us at home," Massachusetts senator Henry Cabot Lodge averred.12

The social malaise also aroused concern about issues of manhood. The depression robbed many American men of the means to support their families. A rising generation that had not fought in the Civil War and remembered only its glories increasingly feared that industrialism, urbanization, and immigration, along with widening divisions of class and race, were sapping American males of the manly virtues deemed essential for good governance. The emergence of a militant women's movement demanding political participation further threatened men's traditional role in U.S. politics. For some jingoes, a more assertive foreign policy, war, and even the acquisition of colonies would reaffirm their manhood, restore lost pride and virility, and legitimize their traditional place in the political system. "War is healthy to a nation," an Illinois congressman proclaimed. "War is a bad thing, no doubt," Lodge added, "but there are far worse things both for nations and for men," among which he would have included dishonor and a failure vigorously to defend the nation's interests.13

Changes at home and abroad convinced some Americans of the need to reexamine long-standing foreign policy assumptions. The further shrinkage of distances, the advent of menacing weapons, the emergence of new powers such as Germany and Japan, and the surge of imperialist activity persuaded some military leaders that the United States no longer enjoyed freedom from foreign threat. Isolated from civilian society, increasingly professionalized, their own interests appearing to be happily aligned with those of the nation, they pushed for a reexamination of national defense policy and the building of a modern military machine. They promoted the novel idea (for Americans, at least) that even in time of peace a nation must prepare for war. Army officers added Germany and Japan to the nation's list of potential enemies and warned of emerging threats from European imperialism, commercial rivalries, and foreign challenges to an American-controlled canal. They began to push for an expanded, more professional regular army based on European models.14

Advocates for the new navy offered more compelling arguments and achieved greater results. The most fervent and influential late nineteenth-century advocate of sea power was Capt. Alfred Thayer Mahan, son of an early superintendent of West Point. A mediocre sailor who detested sea duty, the younger Mahan salvaged a flagging career by accepting the post of senior lecturer at the new Naval War College. While putting together a course in naval history, he wrote his classic The Influence of Seapower upon History (1890). Mahan argued that the United States must abandon its defensive, "continentalist" strategy based on harbor defense and commerce raiding for a more outward-looking approach. Britain had achieved great-power status by controlling the seas and dominating global commerce. So too, he contended, the United States must compete aggressively for world trade, build a large merchant marine, acquire colonies for raw materials, markets, and naval bases, and construct a modern battleship fleet, "the arm of offensive power, which alone enables a country to extend its influence outward." Such moves would ensure U.S. prosperity by keeping sea lanes open in time of war and peace. A skilled publicist as well as an influential strategic thinker, Mahan won worldwide acclaim in the 1890s; his book became an international best seller. At home, a naval renaissance was already under way. Mahan's ideas provided a persuasive rationale for the new battleship navy and a more aggressive U.S. foreign policy.15

Some civilians also called for an activist foreign policy, even for abandoning long-standing strictures against alliances and inhibitions against overseas expansion. Such policies had done well enough "when we were an embryo nation," a senator observed, but the mere fact that the United States had become a major power now demanded their abandonment.16 As a rising great power, the United States had interests that must be defended. It must assume the responsibility for its own welfare and for world order that went with its new status. "The mission of this country is not merely to pose but to act . . . ," former attorney general and secretary of state Richard Olney proclaimed in 1898, "to forego no fitting opportunity to further the progress of civilization."17

Since Jefferson's time, Americans had sought to deal with pressing internal difficulties through expansion, and in the 1890s they increasingly looked outward for solutions to domestic problems. With the disappearance of the frontier, it was argued, new outlets must be found abroad for America's energy and enterprise. In a world driven by Darwinian struggle where only the strongest survived, the United States must compete aggressively. The Panic of 1893 marked the coming of age of the "glut thesis." America's traditional interest in foreign trade now became almost an obsession. Businessmen increasingly looked to Washington for assistance.18 Many Americans agreed that to compete effectively in world markets the United States needed an isthmian canal and island bases to protect it. In the tense atmosphere of the 1890s, some advocates of the so-called large policy even urged acquisition of colonies.

The idea of overseas empire ran up against the nation's tradition of anti-colonialism, and in the 1890s, as so often before, Americans heatedly debated the means by which they could best fulfill their providential destiny. A rising elite keenly interested in foreign policy followed closely similar debates on empire in Britain and adapted their arguments to the United States.19 Some continued to insist that the nation should focus on perfecting its domestic institutions to provide an example to others. But as Americans became more conscious of their rising power, others insisted they had a God-given obligation to spread the blessings of their superior institutions to less fortunate peoples across the world. God was "preparing in our civilization the die with which to stamp nations," Congregationalist minister Josiah Strong proclaimed, and was "preparing mankind to receive our impress."20

Racism and popular notions of Anglo-Saxonism and the white man's burden helped justify the imposition of U.S. rule on "backward" populations. Even while the United States and Britain continued to tangle over various issues, Americans hailed the blood ties and common heritage of the English-speaking peoples. According to Anglo-Saxonist ideas, Americans and Britons stood together at the top of a hierarchy of races, superior in intellect, industry, and morality. Some Americans took pride in the glory of the British Empire while predicting that in time they would supplant it. The United States was bound to become "a greater England with a nobler destiny," proclaimed Indiana senator and staunch expansionist Albert Jeremiah Beveridge.21 Convictions of Anglo-Saxonism helped rationalize harsh measures toward lesser races. While disfranchising and segregating African Americans at home, some Americans promoted the idea of extending civilization to lesser peoples abroad. Recent experiences with Native Americans provided handy precedents. Expansionists thus easily reconciled imperialism with traditional principles. The economic penetration or even colonization of less developed areas would allegedly benefit those peoples by bringing them the advantages of U.S. institutions. Arguing for the Americanization and eventual annexation of Cuba, expansionist James Harrison Wilson put it all together: "Let us take this course because it is noble and just and right, and besides because it will pay."22

The new mood was early manifest in the assertive diplomacy of President Benjamin Harrison and Secretary of State James G. Blaine. In response to attacks on American missionaries, Harrison joined other great powers in seeking to coerce the Chinese government to respect the rights of foreigners. He also ordered the construction of specially designed gunboats to show the flag in Chinese waters. The bullying of Haiti and Santo Domingo in a futile quest for a Caribbean naval base, the bellicose handling of minor incidents with Italy and Chile, and the abortive 1893 move to annex Hawaii all indicated a distinct shift in the tone of U.S. policy and the adoption of new and more aggressive methods.

A second Grover Cleveland administration (1893–97) killed the Republican effort to acquire Hawaii. Anti-expansionist and anti-annexation, Cleveland had a strong sense of right and wrong in such matters. He recalled the treaty of annexation from the Senate and dispatched James Blount of Georgia on a secret fact-finding mission to Hawaii. Blount also opposed overseas expansion both in principle and on racial grounds. "We have nothing in common with those people," he once exclaimed of Venezuelans. He ignored the new Hawaiian government's frenzied warnings that Japan was waiting to seize the islands if the United States demurred. He concluded, correctly, that most Hawaiians opposed annexation and that the change of government had been engineered by Americans to protect their own profits. His report firmly opposed annexation.23 Facing a divided Congress and a nation absorbed in economic crisis, Cleveland was inclined to restore Queen Liliuokalani to power, but he also worried about the fate of the rebels. The queen had threatened to have their heads—and their property. Unable to get from either side the assurances he sought and unwilling to decide himself, he tossed the issue back to Congress. After months of debate, the legislators could agree only on the desirability of recognizing the existing Hawaiian government. Cleveland reluctantly went along.24

Even the normally cautious and anti-expansionist Cleveland was not immune to the spirit of the age. In January 1894, his administration injected U.S. power into an internal struggle in Brazil. Suspecting (probably incorrectly) that Britain sought to use the conflict to enhance its position in that important Latin American nation, Cleveland dispatched five ships of the new navy, the most imposing fleet the nation had ever sent to sea, to break a rebel blockade and protect U.S. ships and exports. When the navy moved on to show the flag elsewhere, private interests took on the task of gunboat diplomacy. With Cleveland's acquiescence or tacit support, the colorful industrialist, shipbuilder, and arms merchant Charles Flint equipped merchant and passenger ships with the most up-to-date weapons, including a "dynamite gun" that could fire a 980-pound projectile. He dispatched his "fleet" to the coast of Brazil. The mere threat of the notorious dynamite gun helped cow the rebels and keep the government in power, solidifying U.S. influence in Brazil. In November 1894, Brazilians laid the cornerstone to a monument in Rio de Janeiro to James Monroe and his doctrine.25

The following year, the Cleveland administration intruded in a boundary dispute between Britain and Venezuela over British Guiana, rendering a new and more expansive interpretation of that doctrine. The dispute had dragged on for years. Venezuela numerous times sought to draw the United States into it by speaking of violations of Monroe's statement. Each time, Washington had politely declined, and it is not entirely clear why Cleveland now took up a challenge his predecessors had sensibly resisted. He had a soft spot for the underdog. He may have been moved by his fervent anti-imperialism. He was undoubtedly responding to domestic pressures, stirred up in part by the lobbying of a shady former U.S. diplomat now working for Venezuela. Britain appeared particularly aggressive in the hemisphere, and the United States was increasingly sensitive to its position. Some Americans feared the British might use the dispute to secure control of the Orinoco River and close it to trade. More generally, Cleveland responded to the broad threat of a surging European imperialism and the fear that the Europeans might turn their attention to Latin America, thus directly threatening U.S. interests. He determined to use the dispute to assert U.S. preeminence in the Western Hemisphere.26

Significantly, Richard Olney replaced Walter Gresham as secretary of state at this point. Not known for tact or finesse—as attorney general, Olney had just forcibly suppressed the Pullman strike—he quickly set the tone for U.S. intrusion. In what Cleveland called his "twenty-inch gun" (new Dreadnought battleships were equipped with twelve-inch guns), Olney's July 20, 1895, note insisted in prosecutor's language that the Monroe Doctrine justified U.S. intervention and pressed Britain to arbitrate. More important, it claimed hegemonic power. Today "the United States is practically sovereign on this continent," he proclaimed, "and its fiat is law upon the subjects to which it confines its interposition." The New York World spoke excitedly of the "blaze" that swept the nation after Olney's message.27

Even more surprising than the fact of U.S. intrusion and the force of Olney's blast was Britain's eventual acquiescence. At first shocked that the United States should take such an extravagant stand on a "subject so comparatively small," Prime Minister Lord Salisbury delayed four months before replying. He then lectured an upstart nation on how to behave in a grown-up world, rejecting its claims and telling it to mind its own business. Now "mad clean through," as he put it, Cleveland responded in kind. On both sides, as so often in the nineteenth century, talk of war abounded. Once again, U.S. timing was excellent. Britain was distracted by crises in the Middle East, East Asia, and especially South Africa, where war loomed with the Boers. As before, the threat of war evoked from both nations ties of kinship that grew stronger throughout the century. London proposed, then quickly dropped over U.S. objections, a conference to define the meaning of the Monroe Doctrine, a significant concession. It also tacitly conceded the U.S. definition of the Monroe Doctrine and its hegemony in the hemisphere.28

The larger principle more or less settled, the two nations, not surprisingly, resolved their differences at the expense of Venezuela. Neither Anglo-Saxon country had much respect for the third party, "a mongrel state," Thomas Bayard, then serving in London as the first U.S. ambassador, exclaimed dismissively. They were not about to leave questions of war and peace in its hands. Britain agreed to arbitrate once the United States accepted its conditions for arbitration. The two nations then imposed on an outraged Venezuela a treaty providing for arbitration and giving it no representation on the commission. Britain got much of what it wanted except for a strip of land controlling the Orinoco River, precisely what Washington sought to keep from it. Venezuela got very little. Despite Olney's bombast, the United States secured British recognition of its expanded interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine and a larger share of the trade of northern South America. Olney's blast further announced to the world and especially to Britain that the United States was prepared to establish its place among the great powers, whatever Europeans might think. It elevated the Monroe Doctrine to near holy writ at home and marked the end of British efforts to contest U.S. preeminence in the Caribbean.29

From 1895 to 1898, the expansionist program was clearly articulated and well publicized and gained numerous adherents. In the 1896 election campaign between Republican William McKinley of Ohio and Democrat William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska, domestic issues, especially Bryan's pet program, the coinage of silver, held center stage. But the Republican platform set forth a full-fledged expansionist agenda: European withdrawal from the hemisphere; a voluntary union of English-speaking peoples in North America, meaning Canada; construction of a U.S.-controlled isthmian canal; acquisition of the Virgin Islands; annexation of Hawaii; and independence for Cuba. The War of 1898 provided an opportunity to implement much of this agenda—and more.30

What was once called the Spanish-American War was the pivotal event of a pivotal decade, bringing the "large policy" to fruition and marking the United States as a world power. Few events in U.S. history have been as encrusted in myth and indeed trivialized. The very title is a misnomer, of course, since it omits Cuba and the Philippines, both key players in the conflict. Despite four decades of "revisionist" scholarship, popular writing continues to attribute the war to a sensationalist "yellow press," which allegedly whipped into martial frenzy an ignorant public that in turn drove weak leaders into an unnecessary war.31 The war itself has been reduced to comic opera, its consequences dismissed as an aberration. Such treatment undermines the notion of war by design, allowing Americans to cling to the idea of their own noble purposes and sparing them responsibility for a war they came to see as unnecessary and imperialist results they came to regard as unsavory.32 Such interpretations also ignore the extent to which the war and its consequences represented a logical culmination of major trends in nineteenth-century U.S. foreign policy. It was less a case of the United States coming upon greatness almost inadvertently than of it pursuing its destiny deliberately and purposefully.33

The war grew out of a revolution in Cuba that was itself in many ways a product of the island's geographical proximity to and economic dependence on the United States. As with the Hawaiian revolution, U.S. tariff policies played a key role. The 1890 reciprocity treaty with Spain sparked an economic boom on the island. But the 1894 Wilson-Gorman tariff, by depriving Cuban sugar of its privileged position in the U.S. market, inflicted economic devastation and stirred widespread political unrest. Revolutionary sentiment had long smoldered. In 1895, exiles such as the poet, novelist, and patriot leader José Martí returned from the United States to foment rebellion. Concerned about possible U.S. designs on Cuba, Martí, Máximo Gómez, and Antonio Maceo sought a quick victory through scorched earth policies—"abominable devastation," they called it—seeking to turn Cuba into a desert and by doing so drive Spain from the island. Spanish general Valeriano "Butcher" Weyler retaliated with his brutal "reconcentrado" policies, herding peasants into fortified areas where they could be controlled. The results were catastrophic: Ninety-five thousand people died from disease and malnutrition. On the other side, weather, disease, and Cuban arms took a fearsome toll on young and poorly prepared Spanish forces, an estimated thirty-five thousand of them killed each year. The rebels used the machete with especially terrifying effect, littering the sugar and pineapple fields with the heads of Spanish soldiers.34

From the outset, this brutal insurgent war had an enormous impact in the United States. Since Jefferson's day, Cuba's economic and strategic importance had made it an object of U.S. attention. Like Florida, Texas, and Hawaii, the island was Americanized in the late nineteenth century. The Cuban elite was increasingly educated in the United States. By the end of the century, the United States dominated Cuba economically. Exports to the United States increased from 42 percent of the total in 1859 to 87 percent in 1897. United States investments have been estimated at $50 million, trade at $100 million. The war threatened American-owned sugar estates, mines, and ranches and the safety of U.S. citizens. A junta located mainly in Florida and New York and led by Cuban expatriates, some of them U.S. citizens, lobbied tirelessly for Cuba Libre, sold war bonds in the United States, and smuggled weapons onto the island. Cubans naturalized as U.S. citizens returned to fight. Not surprisingly, Cubans had mixed feelings about U.S. assistance. Some conservative leaders lacked confidence in their peoples' ability to govern themselves and feared chaos if the African, former slave population took power. They were amenable to U.S. tutelage—even annexation—to maintain their positions and property. Others like Martí, Gómez, and Maceo, while eager for American backing, feared that military intervention might lead to U.S. domination. "To change masters is not to be free," Martí warned.35

The "yellow press" (so named for the "Yellow Kid," a popular cartoon character that appeared in its newly colored pages) helped make Cuba a cause célèbre in the United States. The mass-circulation newspaper came into its own in the 1890s. The New York dailies of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer engaged in a fierce, head-to-head competition with few restraints and fewer scruples about the truth. They eagerly disseminated stories furnished by the junta. Talented artists such as Frederic Remington and writers such as Richard Harding Davis portrayed the revolution as a simple morality play featuring the oppression of freedom-loving Cubans by evil Spaniards.36 The yellow press undoubtedly contributed to a war spirit, but Americans in areas where it did not circulate also strongly sympathized with Cuba. The Dubuque, Iowa, Times, for example, appealed to "men in whose breast the fire of patriotism burns" for the "annihilation of the Spanish dogs."37 The press did not create the differences between Cuba, Spain, and the United States that proved insoluble. War likely would have occurred without its agitation.

Sympathy for Cuba and outrage with Spain produced demands for intervention and war. Anxieties in the country at large fed a martial fever. Businessmen worried that the Cuban problem might delay recovery from the depression. Some Americans, like the Cuban Creoles, feared that an insurgent victory would threaten U.S. investments and trade. The rising furor quickly took on political ramifications. Divided Democrats sought to reunite their party over the Cuban issue and embarrass the Republicans; Republicans tried to head off the opposition. Elites increasingly agreed that the United States must act. National pride, a resurgent sense of destiny, and a conviction that the United States as a rising world power must take responsibility for world events in its area of influence gave an increasing urgency to the Cuban crisis.38

From the time he took office in 1897, President William McKinley was absorbed in the Cuban problem. Once caricatured as a weakling, the puppet of big business, McKinley has received his due in recent years. His retiring demeanor and refusal to promote himself concealed strength of character and resoluteness of purpose. A plain, down-home man of simple tastes, McKinley had extraordinary political skills. His greatest asset was his understanding of people and his ability to deal with them. Accessible, kindly, and a good listener, he was a master of the art of leading by indirection, letting others seem to persuade him of positions he had already taken, appearing to follow while actually leading. "He had a way of handling men," his secretary of war Elihu Root observed, "so that they thought his ideas were their own."39 He entered the presidency with a clearly defined agenda, including the expansionist planks of the Republican platform. In many ways the first modern president, he used the instruments of his office as no one had since Lincoln, dominating his cabinet, controlling Congress, and skillfully employing the press to build political support for his policies.40

For two years, McKinley patiently negotiated with Spain while holding off domestic pressures for war. Reversing America's long-standing acceptance of Spanish sovereignty, he sought by steadily increasing diplomatic pressure to end Weyler's brutal measures and drive Spain from Cuba without war. For a time, he appeared to succeed. The Madrid government recalled Weyler and promised Cuban autonomy. But his success was illusory. By this time, Spain was willing to concede some measure of self-government. But the insurgents, having spent much blood and treasure, would accept nothing less than complete independence. Spanish officials feared that to abandon the "ever faithful isle," the last remnant of their once glorious American empire, would bring down the government and perhaps the monarchy. They tried to hold off the United States by a policy of "procrastination and dissimulation," deluding themselves that somehow things would work out.41

Two incidents in early 1898 brought the two nations to the brink of war. On February 9, Hearst's New York World published a letter written by Enrique Dupuy de Lôme, Spanish minister in Washington, to friends in Cuba describing McKinley as weak and a bidder for the crowd and speaking cynically of Spain's promises of reforms in Cuba. It was a private letter, of course, and Americans themselves had publicly said much worse things about McKinley. But in the supercharged atmosphere of 1898, this "Worst Insult to the United States in Its History," as one newspaper hyperbolically headlined it, provoked popular outrage. More important, de Lôme's cynical comments about reforms caused McKinley to doubt Spain's good faith.42

Less than a week later, the battleship USS Maine mysteriously exploded in Havana harbor, killing 266 American sailors. The catastrophe almost certainly resulted from an internal explosion, but Americans pinned responsibility elsewhere. "Remember the Maine, to hell with Spain" became a popular rallying cry. Without bothering to examine the facts, the press blamed the explosion on Spain. Theater audiences wept, stamped their feet, and cheered when patriotic songs were played. Jingoes wrapped themselves in flags and demanded war. When McKinley pleaded for restraint, he was burned in effigy. Congress threatened to take matters into its own hands and recognize the Cuban rebels or even declare war.43

McKinley's last-ditch efforts to achieve his aims without war failed. Phrasing his demands in the language of diplomacy to leave room for maneuver, he insisted that Spain must get out of Cuba or face war. In Spain also, opposition to concessions grew. The Spanish resented being blamed for the Maine. The threat of U.S. intervention in Cuba provoked among students, middle-class urbanites, and even some working-class people a surge of patriotism not unlike that in the United States. A jingoist spirit marked bullfights and fiestas. Street demonstrations rocked major Iberian cities. In Málaga, angry mobs threw rocks at the U.S. consulate amidst shouts of "Viva España! Muerte a los Yanques! Abajo el armisticio!" As in the United States, the press incited popular outrage.44 Fearing for its survival and even for the monarchy, the government recognized that it could not win a war with the United States and feared disastrous consequences. In keeping with the spirit of the era, however, it preferred the honor of war to the ignominy of surrender. It offered last-minute concessions to buy time but refused to surrender on the fundamental issue.

Since he left scant written record, it is difficult to determine why McKinley finally decided upon war. He was understandably sensitive to the mounting political pressures and stung by charges of spinelessness. But he appears to have found other, more compelling reasons to act. Historians disagree sharply on the state of the insurgency, some arguing that the rebels were close to victory, others that the war had ground into a bloody stalemate.45 McKinley found either prospect unacceptable. An insurgent triumph threatened American property and investments as well as ultimate U.S. control of Cuba. Memories of another Caribbean revolution a century earlier had not died, and in the eyes of some Americans Cuba raised the grim specter of a second Haiti. Continued stalemate risked more destruction on the island and an unsettled situation at home. It was therefore not so much the case of an aroused public forcing a weak president into an unnecessary war as of McKinley choosing war to defend vital U.S. interests and remove "a constant menace to our peace" in an area "right at our door."46

The ambiguous manner in which the administration went to war belied its steadfastness of purpose. True to form, the president did not ask Congress for a declaration. Rather, he let the legislators take the initiative, the only instance in U.S. history in which that has happened. He sought "a neutral intervention" that would leave him maximum freedom of action in Cuba. His supporters in Congress warned that it would be a "grave mistake" to recognize a "people of whom we know practically nothing." They affirmed that the president must be in a position to "insist upon such a government as will be of practical advantage to the United States." McKinley successfully headed off those zealots who sought to couple intervention with recognition of Cuban independence. But he could not thwart the so-called Teller Amendment providing that the United States would not annex Cuba once the war ended. The amendment derived from various forces, those who opposed annexing territory containing large numbers of blacks and Catholics, those who sincerely supported Cuban independence, and representatives of the domestic sugar business, including sponsor Senator Henry Teller of Colorado, who feared Cuban competition. McKinley did not like the amendment, but he acquiesced. Cubans remained suspicious, warning that the Americans were a "people who do not work for nothing."47

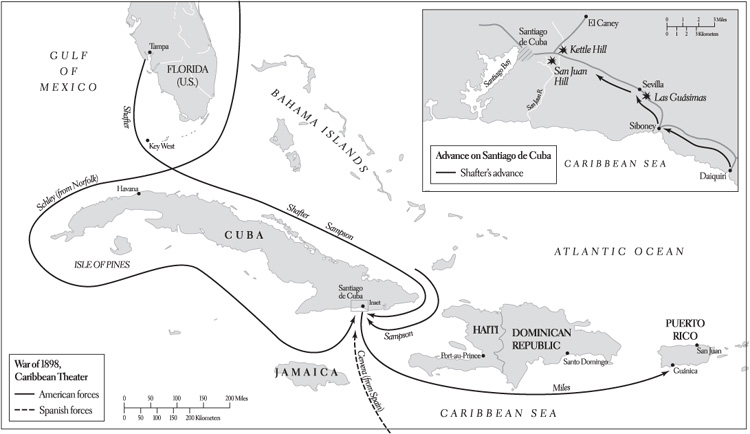

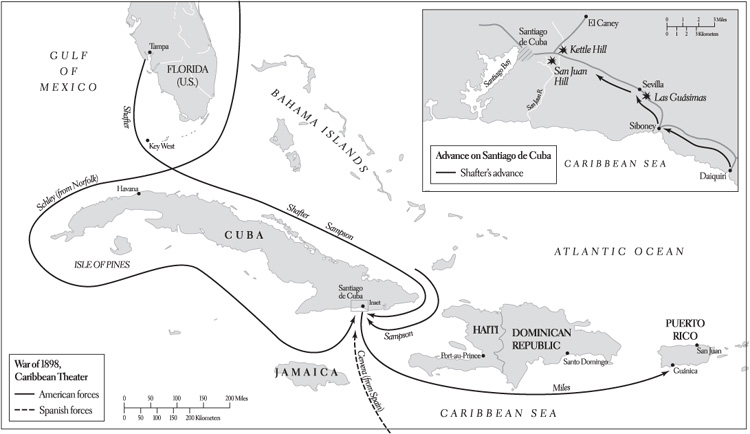

By modern military standards, the War of 1898 did not amount to much. On the U.S. side, the last vestiges of nineteenth-century voluntarism and amateurism collided with an incipient twentieth-century military professionalism, creating confusion, mismanagement, and indeed, at times, comic opera. Volunteers responded in such numbers that they could not be absorbed by a sclerotic military bureaucracy. Large numbers of troops languished in squalid camps where they fought each other and eventually

drifted home. Americans arrived in Cuba's tropical summer sun in woolen uniforms left over from the Civil War. They were fed a form of canned beef variously described as "embalmed" and "nauseating." The U.S. commander, Gen. William Shafter, weighed more than three hundred pounds and resembled a "floating tent." Mounting his horse required a complicated system of ropes and pulleys, a feat of real engineering ingenuity.

Despite ineptitude and mismanagement, victory came easily, causing journalist Richard Harding Davis to observe that God looked after drunkards, babies, and Americans. With McKinley's approval, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt had ordered Adm. George Dewey's fleet to steam to the Philippines. In a smashing victory that set the tone for and came to symbolize the war, Dewey's six new warships crushed the decrepit Spanish squadron in Manila Bay, setting off wild celebrations at home, sealing the doom of Spain's empire in the Philippines, and creating an opportunity for and enthusiasm about expansionism. Victory in Cuba did not come so easily. United States forces landed near Santiago without resistance, the result of luck as much as design. But they met stubborn Spanish resistance while advancing inland and in taking the city suffered heavy losses from Spanish fire and especially disease. Exhausted from three years of fighting Cubans, Spanish forces had no desire to take on fresh U.S. troops. Food shortages, mounting debt, political disarray, and a conspicuous lack of support from the European great powers sapped Spain's enthusiasm for war.48 It took less than four months for U.S. forces to conquer Cuba (just as disease began to decimate the invading force). Victory cost a mere 345 killed in action, 5,000 lost to illness, and an estimated $250 million.

The ease and decisiveness of the victory intoxicated Americans, stoking an already overheated chauvinism. "It was a splendid little war," Ambassador John Hay chortled from London (giving the conflict an enduring label), "begun with the highest motives, carried on with magnificent intelligence and spirit, favored by that fortune which loves the brave." "No war in history has accomplished so much in so short a time with so little loss," concurred the U.S. ambassador to France. The ease of victory confirmed the rising view that the nation stood on the brink of greatness.49

In the national mythology, the acquisition of empire from a war often dismissed with caricature has been viewed as accidental or aberrational, an ad hoc response to situations that had not been anticipated. In fact, the administration conducted the war with a clarity and resoluteness of purpose that belied its comic opera qualities. The first modern commander in chief, McKinley created a War Room on the second floor of the White House and used fifteen telephone lines and the telegraph to coordinate the Washington bureaucracy and maintain direct contact with U.S. forces in Cuba.50 More important, he used the war to advance America's status as a world power and achieve its expansionist objectives. He set out to remove Spain from the Western Hemisphere, completing a process begun one hundred years earlier. Moving with characteristic stealth, he kept rebel forces in Cuba and the Philippines at arm's length to ensure maximum U.S. control and freedom of choice. Until the war ended, he asserted, "we must keep all we get; when the war is over we must keep what we want."51

McKinley used the exigencies of war to fulfill the old aim of annexing Hawaii. Upon taking office, he had declared annexation but a matter of time—not a new departure, he correctly affirmed, but a "consummation."52 "We need Hawaii as much as in its day we needed California. It was Manifest Destiny," he stated on another occasion.53 A perceived threat from Japan underscored the urgency. Hawaii had encouraged the immigration of Japanese workers to meet a labor shortage, but by the mid-1890s an influx once welcomed had aroused concern. When the government sought to restrict further immigration, a Japan puffed up by victory over China vigorously protested and dispatched a warship to back up its words. McKinley sent a new treaty of annexation to the Senate in June 1897, provoking yet another Japanese protest and a mini war scare (one U.S. naval officer actually predicted a Japanese surprise attack on the Hawaiian Islands). Advocates of annexation insisted that the United States must "act NOW to preserve the results of its past policy, and to prevent the dominancy of Hawaii by a foreign people."54 The anti-imperialist opposition had the votes to forestall a two-thirds majority. The administration thus followed John Tyler's 1844 precedent by seeking a joint resolution. In any event, by early 1898 the emerging crisis with Spain put a premium on caution.

What had once been a deterrent soon spurred action. Relentlessly pursuing annexation, Hawaii's pro-American government opened its ports and resources to the United States instead of proclaiming neutrality. The war made obvious Hawaii's strategic importance. Worries about German and Japanese expansion in the Pacific reinforced the point. Hawaii assumed a major role in supplying U.S. troops in the Philippines. McKinley even talked of annexing it under presidential war powers. Shortly after the outbreak of war, he submitted to Congress a resolution for annexation. Legislators declared Hawaii a "naval and military necessity," the "key to the Pacific"; not to annex would be "national folly," one exclaimed. The resolution passed in July by sizeable majorities. The haole (non-Hawaiian) ruling classes cheered. Some native Hawaiians lamented that "Annexation is Rotten Bananas." One group issued a futile protest against "annexation . . . without reference to the consent of the people of the Hawaiian Islands." The Women's Patriotic League sewed hatbands declaring "Ku'u Hae Aloha"(I Love My Flag).55

While fighting in Cuba, the United States also moved swiftly to take Puerto Rico before the war ended. Named "wealthy port" by its first Spanish governor, the island occupied a commanding position between the two ocean passages. It was called the "Malta of the Caribbean" because it could guard an isthmian canal and the Pacific coast as that Mediterranean island protected Egypt. In contrast to Cuba, the United States had little trade with and few investments in Puerto Rico. But Blaine had put it on his list of necessary acquisitions, mainly as a base to guard a canal. By preventing the United States from taking Cuba, the Teller Amendment probably increased the importance of Puerto Rico. Once the United States was at war with Spain, Puerto Rico provided another chance to remove European influence from the hemisphere. From his debarkation point in Texas, Rough Rider and ardent expansionist Theodore Roosevelt urged his imperialist cohort Senator Lodge to "prevent any talk of peace until we get Porto Rico and the Philippines as well as secure the independence of Cuba."56 Once war began, some businessmen recommended taking Puerto Rico for its commercial and strategic value. Protestant missionaries expressed interest in opening the island— already heavily Roman Catholic—to the "Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ."57 By late June, if not earlier, the administration was committed to its acquisition, ostensibly as payment for a costly intervention.

The main U.S. concern was to seize Puerto Rico before Spain sued for peace. On July 7, the White House ordered Gen. Nelson A. Miles to proceed to Puerto Rico as soon as victory in Cuba was secured. Miles landed at Guánica on July 25 without significant opposition—indeed, the invaders were greeted with shouts of "viva" and given provisions. Puerto Rico was relatively peaceful and prosperous. Its people enjoyed a large measure of autonomy under Spain. They looked favorably upon the United States; many were prepared to accept its tutelage. Thus even after the invaders made clear they intended to take possession of the island, they encountered only sporadic and scattered opposition and suffered few casualties. United States forces characterized the invasion as a "picnic." The only shortage was of American flags for the Puerto Ricans to wave.58 The occupation was completed just in time. On August 7, Spain asked for peace terms. It had hoped to hang on to Puerto Rico, but the United States insisted upon taking the island in lieu of "pecuniary indemnity."59

The island land grab extended to the Pacific. Increased great-power interest in East Asia heightened the importance of the numerous islands scattered along Pacific sea routes. Prior to 1898, Germany, Great Britain, and the United States were already engaged in a lively competition. To secure a coaling station for ships en route to the southwest Pacific, McKinley on June 3 ordered the navy to seize one of the Mariana Islands strategically positioned between Hawaii and the Philippines. Three U.S. ships subsequently stopped at Guam. In a scene worthy of a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta, they announced their arrival by firing their guns. Not knowing the two nations were at war, the Spanish garrison apologized for not being able to answer what they thought was an American salute because they had no ammunition. Spanish defenders were taken prisoner and the island seized. With Guam and the Philippines, the United States saw the need for a cable station to better communicate with its distant possessions. Wake Atoll, a tiny piece of uninhabited land in the central Pacific, seemed suitable. Although Germany had strong claims, U.S. naval officers seized Wake for the United States in January 1899. Mainly eager to solidify its claims to Samoa, Germany did not contest the U.S. claim. As it turned out, Wake Island did not prove feasible for a cable relay station. The United States did nothing more to establish its sovereignty.60

McKinley moved with more circumspection on the Philippines. It remains unclear exactly when he decided to annex the islands. He first hinted they might be left in Spanish hands; the United States would settle for a port. He later suggested that the issue might be negotiated. Even before he received official confirmation of Dewey's victory, however, he dispatched twenty thousand soldiers to establish U.S. authority in the Philippines. Permitting missionary and business expansionists to persuade him of what he may already have believed, he apparently decided as early as the summer of 1898 to take all the islands. Moving with customary indirection, he helped shape the outcome he sought. He used extended speaking tours through the Middle West and South to mobilize public opinion. He stacked the peace commission with expansionists. He made a conscious decision appear the result of fate and destiny, proclaiming by the time negotiations began that he could see "but one plain path of duty—the acceptance of the archipelago." In December 1898, his negotiators thus imposed on a reluctant but hapless Spain the Treaty of Paris, calling for the cession of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. The United States awarded Spain a booby prize of $20 million.61

Dealing with insurgent forces in Cuba and the Philippines proved more complex and costly. Americans took to Cuba genuine enthusiasm for a noble cause, "the first war of its kind," a fictional soldier averred. "We are coming with Old Glory," a popular song proclaimed.62 Their idealism barely outlasted their initial encounters with Cuban rebels. Viewing Cuba Libre through the idealized prism of their own revolution, Americans were not prepared for what they encountered. They had no sense of what a guerrilla army three years in the field might look like. They brought with their weapons and knapsacks the heavy burden of deeply entrenched racism. The Cubans thus appeared to them "ragged and half-starved," a "wretched mongrel lot," "utter tatterdemalions." From a military standpoint, they seemed useless, not worthy allies. Their participation was quickly limited to support roles, the sort of menial tasks African Americans were expected to perform at home. The proud rebels' rejection of such assignments reinforced negative stereotypes. Indeed, Americans came to look more favorably upon the once despised Spanish soldiers, viewing them as a source of order, a safeguard for property, and a protection against a possible race war.63

Popular perceptions nicely complemented the nation's political goals. Cuba in fact had made significant progress toward self-government in the last days of Spanish rule, but this was lost on the invaders. The ragtag Cubans were no more fit for self-government than "gunpowder is for hell," General Shafter thundered, and from the moment they landed Americans set out to establish complete control regardless of the Teller Amendment.64 The United States ignored the provisional government already in place and refused to recognize the insurgents or army. It did not consult Cubans regarding peace aims or negotiations and did not permit them even a ceremonial role in the surrender at Santiago or the overall surrender of the island. They were required to recognize the military authority of the United States, which, to their consternation, refused any commitment for future independence.

The United States handled the Philippines in much the same way. There as in Cuba, Americans encountered revolution, the first anti-colonial revolt in the Pacific region, a middle-class uprising launched in 1896 by well-educated, relatively prosperous Filipinos such as the twentynine-year-old Emilio Aguinaldo. Seeing the exiled Aguinaldo as possibly useful in undermining Spanish authority, U.S. officials had helped him get home, perhaps deluding him into believing they would not stay. Once there, he declared the islands independent, established a "provisional dictatorship" with himself as head, and even designed a red, white, and blue flag. Americans on the scene conceded that Aguinaldo's group included "men of education and ability" but also conveniently concluded that it did not have broad popular support and could not sustain itself against European predators. McKinley gave no more than fleeting thought to independence and rejected a U.S. protectorate. He instructed the U.S. military to compel the rebels to accept its authority. The United States refused to recognize Aguinaldo's government, as with the Cubans, keeping it at arm's length. In December 1898, McKinley proclaimed a military government. He vowed to respect the rights of Filipinos but made no promises of self-government. On the scene, tensions mounted between U.S. occupation forces and the thirty thousand Filipinos besieging Manila.65

From the late summer of 1898 until after the election of 1900, one of those periodic great debates over the nation's role in the world raged in the United States. The central issue was the Philippines. Defenders of annexation pointed to obvious strategic and commercial advantages, fine harbors for naval bases, a "key to the wealth of the Orient." The islands would themselves provide important markets and in addition furnish a vital outpost from which to capture a share of the fabled China market. The imperialists easily rationalized the subjugation of alien peoples. Indeed, they argued, the United States by virtue of its superior institutions had an obligation to rescue lesser peoples from barbarism and ignorance and bring them the blessings of Anglo-Saxon civilization. As McKinley allegedly put it to a delegation of visiting churchmen, there seemed nothing to do but to "educate the Filipinos, and uplift them and civilize them and Christianize them, and by God's grace do the very best we could by them."66 If America were to abandon the islands after rescuing them from Spain, they might be snapped up by another nation—Germany had displayed more than passing interest. They could fall victim to their own incapacity for self-government. The United States could not in good conscience escape the responsibilities thrust upon it. "My countrymen," McKinley proclaimed in October 1898, "the currents of destiny flow through the hearts of the people . . . . Who will divert them? Who will stop them?"67

An anti-imperialist movement including some of the nation's political and intellectual leaders challenged the expansionist argument on every count. Political independents, the anti-imperialists eloquently warned that expansion would compromise America's ideals and its special mission in the world.68 The acquisition of overseas territory with no prospect for statehood violated the Constitution. More important, it undermined the republican principles upon which the nation was founded. The United States could not join the Old World in exploiting other peoples without betraying its anti-colonial tradition. The acquisition of overseas empire would require a large standing army and higher taxes. It would compel U.S. involvement in the dangerous power politics of East Asia and the Pacific.

At the outbreak of war in 1898, the philosopher William James marveled at how the nation could "puke up its ancient soul . . . in five minutes without a wink of squeamishness." He denounced as "snivelling," "loathsome" cant talk of uplifting the Filipinos. The U.S. Army was at that time suppressing an insurrection with military force, and that, he argued, was the only education the people could expect. "God damn the U.S. for its vile conduct in the Philippines," he exploded.69 Industrialist Andrew Carnegie, contending that the islands would drain the United States economically, offered to buy their independence with a personal check for $20 million. Other anti-imperialists warned that any gains from new markets would be offset by harmful competition with American farmers. Some argued that the United States already had sufficient territory. "We do not want any more States until we can civilize Kansas," sneered journalist E. L. Godkin.70 Many anti-imperialists objected on grounds of race. "Pitchfork Ben" Tilman of South Carolina vehemently opposed injecting into the "body politic of the United States . . . that vitiated blood, that debased and ignorant people."71 The nation already had a "black elephant" in the South, the New York World proclaimed. Did it "really need a white elephant in the Philippines, a leper elephant in Hawaii, a brown elephant in Porto Rico and perhaps a yellow elephant in Cuba?"72

The anti-imperialists may have made the stronger case over the long run, but the immediate outcome was not determined by logic or force of argument. The administration had the advantage of the initiative, of offering something positive to a people still heady from military triumphs. Many Americans found seductive the February 1899 appeal of British poet Rudyard Kipling to take up the "white man's burden," first published just days before the Senate took up the issue of annexation. The Republicans also had a solid majority in the Senate. A remarkably heterogeneous group, the anti-imperialists were divided among themselves and lacked effective leadership. They had to "blow cold upon the hot excitement," as James put it.73 In an early example of foreign policy bipartisanship, William Jennings Bryan, the titular leader of the Democratic opposition, vitiated the anti-imperialist cause and infuriated its leaders by instructing his followers to vote for the peace treaty with Spain, which provided for annexation of the Philippines, in order to end the war. The Philippines could be dealt with later. The outbreak of war in the Philippines on the eve of the Senate vote solidified support for the treaty. In what Lodge called "the hardest, closest fight I have ever known," the Senate approved the treaty 57–21 in February 1899, a bare one vote more than necessary, and a result facilitated by the defection of eleven Democrats.74 McKinley was easily reelected in 1900 in a campaign in which imperialism was no more than a peripheral issue.

As the great debate droned on in the United States, the McKinley administration set about consolidating control over the new empire. The president vowed that the Teller pledge would be "sacredly kept," but he also insisted that the "new Cuba" must be bound to the United States by "ties of singular intimacy and strength." Many Americans believed that annexation was a matter of time and that, as with Texas, California, and Hawaii, it would evolve through natural processes—"annexation by acclamation," one official labeled it. Some indeed thought that the way the United States implemented the occupation would contribute to this outcome. "It is better to have the favors of a lady by her consent, after judicious courtship," Secretary of War Elihu Root observed, "than to ravish her."75 The United States established close ties with Cuban men of property and standing—"our friends," Root called them—many of them expatriates, some U.S. citizens. It created an army closely tied to the United States. It carried out good works. The occupation government imposed ordinances making it easy for outsiders to acquire land, built railroads, and at least indirectly encouraged the emigration of Americans. "Little by little the whole island is passing into the hands of American citizens," a Louisiana journal exclaimed in 1903, "the shortest and surest way to obtain its annexation to the United States."76

The expected outcome did not materialize, and other means had to be found to establish the ties McKinley sought. Except for a small minority of pro-Americans, sentiment for annexation did not develop in Cuba. Nationalism remained strong and indeed intensified under the occupation. The first elections did not go as Americans wanted; some officials continued to fear that Cubans of African descent might plunge the nation into a "Hayti No. 2." The outbreak of war in the Philippines in early 1899 aroused similar fears for Cuba.

Eager to get out but determined to maintain control of a nominally independent Cuba, the United States settled on the so-called Platt Amendment to create and sustain a protectorate. Drafted by Root and attached to a military appropriation bill approved by Congress in March 1901, it forbade Cuba from entering into any treaty that would impair its independence, granting concessions to any foreign power, or contracting a public debt in excess of its ability to pay. It explicitly empowered the United States to intervene in Cuba's internal affairs and provided two sites for U.S. naval bases. "There is, of course, little or no independence left Cuba under the Platt Amendment," military governor Gen. Leonard Wood candidly conceded.77 When Cubans resisted this obvious infringement on their sovereignty with street demonstrations, marches, rallies, and petitions, the United States demanded that they incorporate the amendment into their constitution or face an indefinite occupation. It passed by a single vote. "It is either Annexation or a Republic with an Amendment," one Cuban lamented; "I prefer the latter." "Cuba is dead; we are enslaved forever," a patriot protested.78

A 1903 reciprocity treaty provided an economic counterpart to the Platt Amendment. The war left Cuba a wasteland. In its aftermath, the United States set out to construct a neo-colonial economic structure built around sugar and tobacco as major cash crops and tied closely to the U.S. market. Without prodding from their government, Americans stepped in to buy up the sugar estates from fleeing Spaniards and destitute Cubans. Using Hawaii as a model, U.S. officials saw in free trade a means to promote annexation by "natural voluntary and progressive steps honorable alike to both parties." Reciprocity would allegedly revive the sugar industry, solidify the position of Cuba's propertied classes, and promote close ties to the United States. It would deepen Cuba's dependence on one crop and one market. The arrangement naturally provoked complaints from U.S. cane and beet growers. Cuban nationalists protested that it would substitute the United States for "our old mother country." Approved in 1903, the agreement provided the basis for Cuban-American economic relations for more than a half century. The War of 1898 thus ended with Cuba as a protectorate of the United States. Not surprisingly, it remained for Cubans a "brooding preoccupation." While Americans remembered the war as something they had done for Cubans and expected Cuba to show gratitude, Cubans saw it as something done to them. The betrayal of 1898 provided the basis for another Cuban revolution at midcentury.79

The acquisition of a Pacific empire elevated the expansionist dream of an isthmian canal to an urgent priority. Defense of Hawaii and the Philippines required easier access to the Pacific, a point highlighted during the war when the battleship Oregon required sixty-eight days to steam from Puget Sound to Cuba. A canal would also give the United States a competitive edge in Pacific and East Asian markets. The availability of long-sought naval bases in the Caribbean now provided the means to defend it. Thus after the war with Spain, the McKinley administration pressed Britain to abrogate the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty. The threat of congressional legislation directing the United States to build a canal without reference to the 1850 treaty pushed the British into negotiations. When the Senate vehemently objected to a treaty giving the United States authority to build and operate but not to fortify a canal, the State Department insisted on reopening negotiations. Preoccupied with European issues and its own imperial war in South Africa and eager for good relations with Washington, London conceded the United States in a treaty finally concluded in November 1901 exclusive right to build, operate, and fortify a canal, an unmistakable sign of acceptance of U.S. preeminence in the Caribbean. The way was clear for initiation of a project that would be carried forward with great gusto by McKinley's successor, Theodore Roosevelt.80

Pacification of the Philippines proved much more difficult and costly. McKinley spoke eloquently of "benevolent assimilation" and insisted that "our priceless principles undergo no change under a tropical sun. They go with the flag."81 But he also ordered the imposition of unchallenged U.S. authority. The United States soon found itself at war with Aguinaldo's insurgents. The Filipinos naively expected to gain recognition of their independence and then counted on the U.S. Senate to defeat the peace treaty. Many Americans viewed the Filipinos with contempt. Tensions increased along their adjoining lines around Manila until an incident in February 1899 provoked war. Americans called it the "Philippine Insurrection," thus branding the enemy as rebels against duly constituted authority. The Filipinos viewed it as a war for independence fought by a legitimate government against an outside oppressor. It became an especially brutal war, hatreds on both sides fueled by nationalism, race, and a tropical sun. It provoked enormous controversy in the United States for a time and then was largely forgotten until obvious if often overdrawn parallels with the war in Vietnam revived interest in the 1960s.

The army of occupation and U.S. civilian officials took seriously McKinley's charge of "benevolent assimilation," seeking to defuse resistance through enlightened colonial policies. The military developed a "pacification" program to win Filipino support, building roads and bridges, establishing schools, tackling the twin scourges of smallpox and leprosy with public health facilities, and distributing food where it was most needed. They began to restructure the Spanish legal system, reform the tax structure, and establish local governments. McKinley sent fellow Ohioan William Howard Taft to the Philippines in 1900 to implement his policies. Taft shared the general American skepticism of Filipino capacity for self-government, but he also accepted McKinley's earnest sense of obligation to America's "little brown brothers." He launched a "policy of attraction," drawing to the United States upper-class ilustrados to govern the islands under colonial tutelage. They helped establish a Filipino political party with its own newspaper and American-style patronage. The United States' colonial policies drained support from Aguinaldo while sparing the nation some of the cost and stigma of direct imperialism. At the same time, U.S. officials on the scene reinforced ties with the old elite from the Spanish era, ensuring that it would remain in power long after they left. They began the process of Americanization of the islands.82

In time, U.S. forces also suppressed the insurgency, no mean feat in an archipelago of seven thousand islands, covering an area of half a million square miles, with a population of seven million people. American volunteers and regulars fought well and maintained generally high morale against an often elusive enemy under difficult conditions, suffocating heat and humidity, drenching monsoon rains, impenetrable jungles, and rugged mountains. After a period of trial and error, the army developed an effective counterinsurgency strategy. Its civic action programs helped win some Filipino support and weaken the insurgency. Later in the war, it added a "policy of chastisement," waging fierce and often brutal campaigns against pockets of resistance. The United States did not commit genocide in the Philippines; atrocities were neither authorized nor condoned. Under the pressures of guerrilla warfare in the tropics, however, brutal measures were employed. Americans came to view the war in racial terms, a conflict of "civilization," in Roosevelt's words, against the "black chaos of savagery and barbarism." The U.S. troops often applied to their Filipino enemy racial epithets such as "nigger," "dusky fellow," "black devil," or "goo-goo" (the last a word of uncertain origin and the basis for "gook" as used by GIs in the Korean and Vietnam wars). The war also gave rise to the word boondock, derived from the Tagalog bonduk, meaning remote, which to soldiers had dark and sinister connotations.83 To secure information about the guerrillas, U.S. troops used the notorious "water cure," allegedly learned from Filipinos who worked with them, in which a bamboo tube was thrust into the mouth of a captive and dirty water—"the filthier the better"—was poured down his "unwilling throat." In Batangas, late in the war, Americans resorted to tactics not unlike those employed by the despised Weyler in Cuba, forcing the resettlement of the population into protected areas to isolate the guerrillas from those who served as their sources of supply. Following the "Batangiga massacre" in which forty-eight Americans were killed, Gen. Jacob Smith ordered that the island of Samar be turned into a "howling wilderness." Although not typical of the war, these events were used to discredit it and came to stamp it. They aroused outrage at home, provoked congressional hearings that lasted from January to June 1902, and revived a moribund anti-imperialist movement.84

Americans too often ascribe the outcome of world events to what they themselves do or fail to do, but in the Philippine War the insurgents contributed mightily to their own defeat. Aguinaldo and his top field commander, a pharmacist, military buff, and admirer of Napoleon, foolishly adopted a conventional war strategy, suffering irreplaceable losses in early frontal assaults against U.S. troops before belatedly resorting to guerrilla tactics. By the time they changed, the war may have been lost.85 Although the Filipinos fought bravely—the bolo-men sometimes with the machetes for which they were named—they lacked modern weapons and skilled leadership. Given the difficulties of geography, they could never establish centralized organization and command. Split into factions, they were vulnerable to U.S. divide-and-conquer tactics. Aguinaldo and other insurgent leaders came from the rural gentry and never identified with the peasantry or developed programs to appeal to them. In some areas, the guerrillas alienated the population by seizing food and destroying property—some Filipinos, ironically, found their needs better met by Americans.86 The insurgents placed far too much hope in the election of Bryan in 1900 and found his defeat hugely demoralizing. The capture of Aguinaldo in March 1901 in a daring raid by Filipino Scouts allied with the United States and posing as rebel reinforcements came at a time when the insurgents were already reeling from military defeats. If not the turning point in the war, it helped break the back of the rebellion, although fighting persisted in remote areas for years.

On July 4, 1902, new president Theodore Roosevelt chose to declare the war ended and U.S. rule confirmed. Victory came at a cost of more than 4,000 U.S. dead and 2,800 wounded, a casualty rate of 5.5 percent, among the highest of any of the American wars. The cost through 1902 was around $600 million. The United States estimated 20,000 Filipinos killed in action and as many as 200,000 civilians killed from war-related causes. At home, the war brought disillusionment with the nation's imperial mission.

The United States had taken an interest in the Philippines in part from concern about its stake in China, and it is no coincidence that acquisition of the islands almost immediately led to a more active role on the Asian mainland. By the late 1890s, China had become a focal point of intense imperial rivalries. For a half century, the European powers—joined by the United States—had steadily encroached on its sovereignty. Following the Sino-Japanese war of 1894–95, the great powers exploited China's palpable weakness to stake out spheres of influence giving them exclusive concessions over trade, mining, and railroads. Germany initiated the process called "slicing the Chinese melon" in 1897. Using the killing of two German missionaries as a pretext, it secured from the hapless imperial government a naval base at Qing Dao along with mining and railroad concessions on the Shandong peninsula. Russia followed by acquiring bases and railroad concessions on the Liaodong peninsula. Britain secured leases to Hong Kong and Kowloon, France concessions in southern China. The powers threatened to reduce the once proud Middle Kingdom to a conglomeration of virtual colonies.87

The U.S. government had shown little interest in China during the Gilded Age, but in the 1890s pressures mounted for greater involvement. Trade and investments enjoyed a boomlet, once again stirring hopes of a bounteous China market. The threat of partition after the Sino-Japanese War produced pressures from the business community to protect the market for U.S. exports. By this time, missionaries had increased dramatically in numbers and penetrated the interior of China. As certain of the rectitude of their cause as the Chinese were of the superiority of their civilization, the missionaries promoted an ideology very much at odds with Confucianism and undermined the power of local elites. Scapegoats in Chinese eyes for growing Western influence, the missionaries were increasingly subjected to violent attacks and appealed to their government to defend them against the barbaric forces that threatened their civilizing mission. Missionaries, along with the "China hands," a small group of diplomats who became self-appointed agents for bringing China into the mainstream of Western civilization, constituted a so-called Open Door constituency that sought to make the United States responsible for preventing further assaults on China's sovereignty and reforming it for its own betterment. Some influential Americans indeed came to view China as the next frontier for U.S. influence, the pivot on which a twentieth-century clash of civilizations might hinge.88

These pressure groups were pushing for an active role in China at precisely the point when the United States was becoming more sensitive to its rising power and prestige in the world. For years, the U.S. government had resisted appeals from missionaries for protection, reasoning that it could hardly ask the Chinese government to take care of Americans when it did not protect Chinese and when its exclusionist policies incurred their wrath. Secretary of State Olney initiated the change. Acting as assertively with China as with the British in Latin America, he proclaimed in 1895 that the United States must "leave no doubt in the mind of the Chinese government or the people in the interior" that it is an "effective factor for securing due right for Americans resident in China."89 To support his strong words, he beefed up the U.S. naval presence in Chinese waters. The United States in the 1890s "dramatically broadened" the definition of missionary "rights" and made clear its intent to defend them.90

Once the Spanish crisis had ended, the McKinley administration also took a stand in defense of U.S. trade in China. The task fell to newly appointed Secretary of State John Hay. At one time Lincoln's private secretary, the dapper, witty, and multitalented Hay had worked in business and journalism and was also an accomplished poet, novelist, and biographer. He had served in diplomatic posts in Vienna, Paris, Madrid, and London before returning to Washington. Independently wealthy, urbane, and extraordinarily well connected, the Indianan was a shrewd politician. Like many Republicans, he had once opposed expansion, but he gave way in the 1890s to what he called a "cosmic tendency."91 Pressured by China hands like W. W. Rockhill, Hay concluded that a statement of the U.S. position on freedom of trade in China would appease American businessmen and possibly earn some goodwill among the Chinese that might benefit the United States commercially. It would convince expansionists the United States was prepared to live up to its responsibilities as an Asian power. In addition, according to one State Department operative, it could be a "trump card for the Administration and crush all the life out of the anti-imperialist agitation."92 Thus in September 1899, Hay issued the first Open Door Note, a circular letter urging the great powers involved in China not to discriminate against the commerce of other nations within their spheres of influence.

The following year, the United States joined Japan and the Europeans in a military intervention in China. Simmering anti-foreign agitation fed by bad harvests, floods, plague, and unemployment boiled over in the summer of 1900 into the Boxer Rebellion, so named because its leaders practiced a form of martial arts called spirit boxing. Blaming foreigners for the ills that afflicted their country, the "Righteous and Harmonious Fists" sought to eliminate the evil. They bore placards urging the killing of foreigners. Certain that their animistic rituals made them invincible—even against bullets—they fought with swords and lances. Armed bands of Boxers numbering as high as 140,000 burned and pillaged across North China, eventually killing two hundred missionaries and an estimated two thousand Chinese converts to Christianity. With the complicity of the empress dowager, the Boxers moved on Beijing. In June 1900, joined by troops of the imperial army, they killed two diplomats—a German and a Japanese—and besieged the foreign legations, leaving some 533 foreigners cut off from the outside world. Often dismissed as fanatical and reactionary, the uprising, as one sensitive and empathetic China hand presciently warned, was also "today's hint to the future," the first shot of a sustained nationalist challenge to the humiliation inflicted on a proud people by the West.93

The great powers responded forcibly. After a first military assault failed to relieve the siege of the legations, they assembled at Tianjin an eight-nation force of some fifty thousand troops and on July 7 took the city. In August 1900, while the world watched, the multilateral force fought its way over eighty miles in suffocating heat and against sometimes stubborn opposition to Beijing. After some hesitation, McKinley dispatched A China Relief Expedition of 6,300 troops from the Philippines to assist in relieving the siege, setting an important precedent by intervening militarily far from home without seeking congressional approval.94 Although collaboration among the various powers was poor—each nation's military force sought to grab the glory—the troops relieved the siege, in the process exacting fierce retribution against the Chinese through killing, raping, and looting. Although late in arriving, the Germans were especially vicious. Kaiser Wilhelm II enjoined his troops to act in the mode of Attila's Huns and "make the name of Germany become known in such a manner in China, that no Chinese will ever again dare look askance at a German."95 The kaiser's statement and the Germans' brutal behavior gave them a name that would follow them into World War I. In a protocol of September 1901, the powers demanded punishment of government officials who had supported the Boxers, imposed on China an indemnity of more than $300 million, and secured the right to station additional troops on Chinese soil.