It was called the Great War, and its costs were horrific, its consequences profound. Between August 1914 and November 1918, the European powers fought it out across a blood-soaked continent. Harnessing modern technology to the ancient art of war, they created a ruthlessly efficient killing machine that left as many as ten million soldiers and civilians dead, countless others wounded and disfigured. The war inflicted huge economic and psychological damage on people and societies; it shattered once mighty empires. It coincided with and in important ways shaped the outbreak of revolutionary challenges to the established economic and political order. Together, the forces of war and revolution unleashed during the second decade of the twentieth century set off an era of conflict that would last nearly until the century's end.

Woodrow Wilson once declared that it would be an "irony of fate" if his presidency focused on foreign policy.1 Indeed, it seems more than a twist of fate if not quite predestination that placed him in the White House during this tumultuous era. He brought to the office an especially keen sense of his own calling to lead the nation and of America's destiny to reshape a war-torn world. From his first days as chief executive, he confronted revolutions in Mexico, China, and later Russia. Initially content to follow the traditional path of U.S. neutrality in Europe's wars, in the face of Germany's U-boat attacks he eventually—and reluctantly—concluded that intervention was necessary to defend his nation's rights and honor and assure for himself and the United States a voice in the peacemaking. Once at war, he gave urgent and eloquent expression to a liberal peace program that fully reflected American ideals dating to the beginning of the republic. He enjoined Americans to assume a leadership position in world affairs. Committing himself and his nation to little short of revolutionizing the international system, he learned through bitter experience that the world was less malleable than he had assumed. He met frustration abroad and bitter defeat at home, a failure that took the form of grand tragedy when a new and even more destructive war broke out less than two decades hence. Yet the ideas he set forth have continued to influence U.S. foreign policy throughout the twentieth century and beyond.

Wilson towers above the landscape of modern American foreign policy like no other individual, the dominant personality, the seminal figure. Born in the South shortly before the Civil War, the son of a Presbyterian minister, from his youth he assiduously prepared himself for leadership—"I have a passion of interpreting great thoughts to the world," he wrote even as a young man.2 After studying law, he earned a doctorate in history and political science at Johns Hopkins University. He became a "public intellectual" before the phrase was coined, establishing a national reputation through his writing and speeches as a keen student of U.S. history and government. Drawn to the world of action, he shifted to university administration and then to politics, as president of Princeton University and subsequently governor of New Jersey demonstrating brilliant leadership in implementing sweeping reform programs against entrenched opposition. Much has been made of his moralism. Like many of his contemporaries, he was a deeply religious man. Religion gave a special fervor to his sense of personal and national destiny. He was also a practical person who quickly grasped the workings of complex institutions and learned how to use them to achieve his goals. Somewhat forbidding of countenance, with high cheekbones, a firm jaw, and stern eyes, he was a shy and private man who could come across as cold and arrogant. Yet among friends he was capable of great warmth; among those he loved, great passion. He was an accomplished and entertaining mimic. His practiced eloquence with the written and spoken word gave him a capacity to sway people matched by few U.S. leaders. Those who worked with him sometimes complained that his absorption in a single matter limited his capacity to deal with other issues. His greatest flaws were his difficulty working with strong people and, once his mind was made up, a reluctance to hear dissenting views.3

Wilson prevailed in 1912 mainly because Republicans were split between party regulars who supported Taft and progressives who backed the increasingly radical Bull Moose candidate Theodore Roosevelt. Socialist Eugene V. Debs won 6 percent of the vote in this most radical election in U.S. history. Wilson came to power fully committed to his New Freedom reform program that sought to restore equality of opportunity and democracy through tariff and banking reform and curbing the power of big business.4

He also brought to the presidency firm convictions about America's role in the world. He fervently believed that foreign policy should serve broad human concerns rather than narrow selfish interests. He recognized business's need for new markets and investments abroad, but he saw no inherent conflict between America's ideals and its pursuit of self-interest, believing, in biographer Kendrick Clements's phrase, that the United States "would do well by doing good."5 He shared in full measure and indeed found religious justification for the traditional American belief that providence had singled out his nation to show other peoples "how they shall walk in the paths of liberty."6 He had watched with fascination his nation's emergence as a world power, and he perceived that this new status put it in a position to promote its ideals. He shared the optimism and goals of the organized peace movement. At first opposed to taking the Philippines, he went along on grounds that nations like the United States and Britain that were "organically" disposed toward democracy should educate other peoples for self-government.7 An admirer of conservative British political philosopher Edmund Burke, he feared disorder and violent change. As at home, he viewed powerful economic interests as obstacles to equal opportunity and democratic progress in other countries.8

Wilson's views were influenced by Col. Edward M. House (the title was honorific), a wealthy Texas politico who without official position remained his alter ego and closest adviser until the last years of his presidency. Small of stature, quiet and self-effacing, House was a shrewd judge of people and a skilled behind-the-scenes operator. His aspirations were revealed in his anonymously published novel, Philip Dru: Administrator, the tale of a Kentuckian and West Point graduate who after corralling the special interests at home launched a crusade with Britain against Germany and Japan for disarmament and the removal of trade barriers.9

Wilson's genuine and deeply felt aspirations to build a better world suffered from a certain culture-blindness. He lacked experience in diplomacy and hence an appreciation of its limits. He had not traveled widely outside the United States and knew little of other peoples and cultures beyond Britain, which he greatly admired. Especially in his first years in office, he had difficulty seeing that well-intended efforts to spread U.S. values might be viewed as interference at best, coercion at worst. His vision was further narrowed by the terrible burden of racism, common among the elite of his generation, which limited his capacity to understand and respect people of different colors. Above all, he was blinded by his certainty of America's goodness and destiny. "A new age has come which no man may forecast," he wrote in 1901. "But the past is the key to it; and the past of America lies at the center of modern history."10

As a scholar, Wilson had written that the power of the president in foreign policy was "very absolute," and he practiced what he had preached, expanding presidential authority even beyond TR's precedents. He was fascinated by the challenge of leading a great nation in tumultuous times. Early in his presidency, he wrote excitedly to a friend about the "thick bundle of despatches" he confronted each afternoon, a "miscellany of just about every sort of problem that can arise in the foreign affairs of a nation in a time of general questioning and difficulty." He distrusted and even had contempt for the State Department, complaining on one occasion that dispatches written there were not in "good and understandable English." Like the professor he had been, he corrected and returned them for resubmission. He composed much diplomatic correspondence on his own typewriter and handled some major issues without consulting either the State Department or his cabinet.11

Wilson's early forays into the world of diplomacy suggest much about the ideas and ideals he brought to office. His naming of William Jennings Bryan as secretary of state was politic in light of the Great Commoner's stature in the Democratic Party and crucial role in the 1912 campaign. It followed a long tradition of appointing the party leader to that important post. Bryan had traveled widely, including an around-the-world jaunt in 1906. In this respect, at least, he was better qualified than Wilson to shape U.S. foreign policy. Even more than Wilson, Bryan believed that Christian principles should animate foreign policy. A longtime temperance advocate, he set the diplomatic community abuzz by refusing to serve alcohol at official functions (the Russian ambassador claimed not to have tasted water for years and to have survived one event only by loading up on claret before he arrived).12 Wilson and Bryan negotiated a treaty with Colombia apologizing and offering monetary compensation for the U.S. role in the Panamanian revolution. This well-intentioned and truly remarkable move quite naturally provoked cries of rage from the Rough Rider, Theodore Roosevelt, and sufficient opposition in the Senate that it was not ratified. It won warm applause in Latin America. In a major speech at Mobile, Alabama, in October 1913, Wilson explicitly disavowed U.S. economic imperialism and gunboat diplomacy in Latin America, linking the exploitative interests that victimized other peoples to the bankers and corporate interests he was fighting at home and promising to replace those old "degrading policies" with a new policy of "sympathy and friendship."13

As war enveloped Europe, Wilson and Bryan sought to implement ideas long advocated by the peace movement. Bryan's agreement to serve had been conditioned on freedom to pursue "cooling off treaties." During 1913–14, ironically as Europe was rushing headlong toward war, he negotiated with twenty nations—Britain and France included—treaties designed to prevent such crises from escalating to military conflict. When diplomacy failed, nations would submit their disputes for study by an international commission and refrain from war until its work was completed. Dismissed by critics then and since as useless or worse, the treaties were indeed shot through with exceptions and qualifications. Bryan nevertheless considered them the crowning achievement of his career. Wilson took them more seriously after the Great War began, even concluding that they might have prevented it. The Bryan treaties marked Wilson's initial move toward an internationalist foreign policy.14

The quest for a Pan-American Pact reveals in microcosm Wilson's larger designs and the obstacles they encountered abroad. Originally proposed by Bryan in late 1913, the idea was embraced by the president after the outbreak of war in Europe. Viewing it as a means to preserve peace following the war, he rewrote it on his own typewriter. It called for mutual guarantees among hemispheric nations of political independence and territorial integrity "under republican government" and for member governments to take control of the production and distribution of arms and munitions. He later linked the pact with U.S. efforts to expand trade in Latin America. Presented first to Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, it drew suspicion. Chile especially feared that its consent would affect its ongoing border dispute with Peru. More important, politicians were alarmed by the huge expansion of U.S. trade and feared that, despite his soothing words, Wilson no less than his predecessors wished to dominate the hemisphere economically and might use the provision calling for republican government to impose U.S. values. Chilean objections delayed consideration of the treaty; U.S. military intervention in Mexico doomed it. It became the basis of Wilson's later proposals for a League of Nations15

From the outset, Wilson grappled with the complex issues raised by revolution. These early twentieth-century upheavals erupted first in East Asia and Latin America. Although they shared the aim of overthrowing established orders, they were as diverse as the nations in which they occurred. In China, reformers inspired by Japan and the West sought to replace a monarchical, feudal order with a modern nation-state. In Mexico, middle- and lower-class revolutionaries challenged the power of entrenched economic and political interests and the Catholic Church. In each case, nationalists sought to eliminate or at least curb the power of foreign interests that had undermined their country's sovereignty and economic independence.

Wilson's response to these revolutions revealed his good intentions and the difficulties of their implementation. Traditionally, the United States had sympathized with revolutions at least in principle, but when they turned violent or radical or threatened U.S. interests, it had called for order or sought to channel them in moderate directions.16 With China and Mexico, Wilson plainly sympathized with the forces of revolution. He understood better than most Americans the way in which they expressed the desire of people for economic and political progress. Even in Central America, he hoped to seize the opportunity to improve the lot of the peoples involved. Wilson's "ethnocentric humanitarianism" failed to recognize that in seeking to direct the future of these nations he limited their ability to work out their own destiny. His presumptuous interference overlooked their own national pride and aspirations.17

After a decade of agitation, nationalist reformers in late 1911 overthrew the moribund Qing regime. Upon taking office, Wilson responded enthusiastically and optimistically to the Chinese Revolution. True to his reformist instincts and taking his cues mainly from missionaries, he concluded that China was "plastic" in the hands of "strong and capable Westerners." He and Bryan believed that the United States should serve as a "friend and exemplar" in moving China toward Christianity and democracy. They also agreed that "men of pronounced Christian character" should be sent there.18 Wilson took bold steps to help China. In March 1913, without consulting the State Department, he withdrew the United States from the international bankers' consortium formed by Taft and Knox to underwrite loans to China. Certain that the Europeans preferred a weak and divided China, a week later and without consulting them he recognized strongman Yüan Shih-k'ai's Republic of China. The open door, he proclaimed, was a "door of friendship and mutual advantage . . . the only door we care to enter."19

Wilson's gestures did nothing to alter the harsh realities in China. In its early stages, the revolution brought little substantive change. The masses were not involved. Leaders sought to advance their own power rather than build a modern state. Reformers fought with each other; Yüan's government was shaky at best. The powers sought to exploit China's weakness to expand their influence. Continued U.S. involvement in the consortium might have helped check Japanese and European ambitions. Wilson's well-intentioned withdrawal thus did as much harm as good. He subsequently rejected China's request for loans, making clear the limits of American support.

The outbreak of war in Europe exposed even more starkly the limits of U.S. helpfulness. "When there is a fire in a jeweler's shop the neighbours cannot be expected to refrain from helping themselves," a Japanese diplomat candidly admitted.20 Japan immediately joined the Allies and took advantage of Europe's preoccupation to drive the Germans from Shandong province. In early 1915, Tokyo presented the embattled Chinese government with its Twenty-One Demands, which sought mainly to legitimize gains made at Germany's expense and expand Japanese influence in Manchuria and along the coast. Even more intrusively, Tokyo demanded that China accept Japanese "advisers" and share responsibility for maintaining order in key areas.

The Chinese sought U.S. support in resisting Japan. Some nationalists saw the United States as little different than other imperial powers; others admired and hoped to emulate it. Still others viewed it as the least menacing of the powers and hoped to use it to counter more aggressive nations. Yüan hired an American to promote his cause and used missionaries and diplomats to gain support from Washington. Working through the U.S. minister, he appealed to the United States to hold off Japanese pressures.

Although deeply concerned with Japanese actions, Wilson and his advisers were not inclined to intercede. State Department counselor Robert Lansing concluded that it would be "quixotic in the extreme to allow the question of China's territorial integrity to entangle the United States in international difficulties."21 True to his pacifist principles, Bryan gave higher priority to avoiding war with Japan than to upholding the independence of China. He made clear the United States would do nothing. Preoccupied with the European war and the death of his beloved wife, Ellen, Wilson at first did not dissent. He continued to sympathize with China, however, informing Bryan that "we should be as active as the circumstances permit" in championing its "sovereign rights."22 Wilson's firmer stance combined with British protests and divisions within the Tokyo government led Japan to moderate its demands.

Wilson continued to take limited measures to help China. In 1916, he encouraged private bankers to extend loans, both to preserve U.S. economic interests and to counter Japanese influence. Soon after, he retreated from his 1913 position by authorizing a new international consortium of bankers to provide loans, even agreeing to help them collect if the Chinese defaulted. Alarmed by America's more assertive stance, Japan sent a special emissary to Washington in the summer of 1917. Kikujiro Ishii's discussions with Lansing, who was by this time secretary of state, revealed major differences, but the two nations eventually got around them by agreeing that Japan's geographical propinquity gave it special but not paramount interests in China. In a secret protocol, the United States again pushed for the open door. The two nations agreed not to exploit the war to gain exclusive privileges. Wilson's position revealed his continuing concern for the Chinese Revolution and Japanese intrusion but made clear to both nations his unwillingness to act.23

Closer to home, the United States had no such compunctions. In Central America and the Caribbean, revolution was an established part of the political process, its aims, at least in U.S. eyes, less about democracy and progress than power and spoils. The growing U.S. economic and diplomatic presence had further destabilized an already volatile region while the opening of the Panama Canal and the outbreak of war in Europe heightened U.S. anxiety about the area. The United States had vital interests there. It also had the power and was willing to use it to contain revolutions and maintain hegemony over small, weak states whose people were deemed inferior. "We are, in spite of ourselves, the guardians of order and justice and decency on this Continent," a Wilson confidant wrote in 1913. "[We] are providentially, naturally, and inescapably, charged with maintenance of humanity's interest here."24

During the campaign and the early days of his presidency, Wilson had denounced Taft's dollar diplomacy and military interventionism and spoken eloquently of treating Latin American nations "on terms of equality and honor."25 He and Bryan genuinely hoped to guide these peoples—"our political children," Bryan called them—to democracy and freedom. They sought to understand their interests even when they conflicted with those of the United States. However they packaged it, the two men ended up behaving much like their predecessors. Wilson deemed it "reprehensible" to permit foreign nations to secure financial control of "these weak and unfortunate republics." But he endorsed a form of dollar diplomacy to control their finances.26 He and Bryan looked upon them with the same sort of paternalism with which they regarded African Americans at home. They assumed that U.S. help would be welcomed. When it was not, they fell back on diplomatic pressure and military force.27

The result was a period of military interventionism exceeding that of Roosevelt and Taft. During its two terms in office, the administration sent troops to Cuba once, Panama twice, and Honduras five times. Wilson and Bryan added Nicaragua to an already long list of protectorates. Despite his anti-imperialist record, Bryan sought to end a long period of instability there with a treaty like the Platt Amendment that would have given the United States the right to intervene. When the Senate rejected this provision, the administration negotiated a treaty giving the United States exclusive rights to the Nicaraguan canal route, a preemptive move

depriving Nicaragua of a vital bargaining lever, and providing for a Dominican-type customs receivership that facilitated U.S. economic control and reduced Nicaragua to protectorate status.28

Because of its position astride the Windward Passage, the island of Hispaniola was considered especially important. Dollar diplomat Jacob Hollander boasted in 1914 that the U.S. protectorate had accomplished in the Dominican Republic "little short of a revolution . . . in the arts of peace, industry and civilization."29 It had not produced stability. Efforts by the United States in 1913 to impose order through supervised elections, the so-called Wilson Plan, provoked the threat of a new revolution and civil war. Dominicans ignored Bryan's subsequent order for a moratorium on revolution. All else failing, Wilson ordered military intervention in 1915 and full-scale military occupation the next year.30

The administration also sent troops to neighboring Haiti. Partly by its own choice, the United States traditionally had little influence in Haiti, although it had coveted the Môle St. Nicolas, one of the Caribbean's finest ports. Historically, the black republic had been most influenced by France; after the turn of the century, German merchants and bankers secured growing power over its economy. Wilson viewed rising European influence as "sinister." United States officials ascribed more credence than warranted to rumors of German establishment of a coaling station at the mole and to the even more bizarre report—after the outbreak of World War I—of a joint French-German customs receivership. Bryan set aside his anti-imperialist views long enough to try to take the mole "out of the market" with a preemptive purchase. He subsequently attempted to head off any European initiative by imposing on Haiti a Dominican-type customs arrangement. Haiti defiantly resisted U.S. overtures, but an especially brutal revolution in which the government massacred some 167 citizens and the president was killed and his dismembered body dragged through the streets provided ample reason for U.S. intervention. In July 1915, allegedly as a strategic measure and to restore order, the United States placed Haiti under military occupation. Wilson admitted that U.S. actions in that "dusky little republic" were "highhanded," but he insisted that in the "unprecedented" circumstances the "necessity for exercising control there is immediate, urgent, imperative." The better elements of the country would understand, he hoped, that the United States was there to help, not subordinate, the people.31

Whatever Wilson's intentions, the military occupations on Hispaniola represent major blots on the U.S. record. The United States imposed at the point of a gun the stability it so desperately sought, but at great cost to the local peoples and to its own ideals. In the Dominican Republic, the U.S. Marines fought a nasty five-year war against stubborn guerrillas in the eastern part of the country, often applying brutal methods against those they contemptuously labeled "spigs." Using models developed in Puerto Rico and the Philippines, U.S. proconsuls implemented technocratic progressive reforms, building roads and developing public health and sanitation programs. The reforms benefited mainly elites and foreigners. Little changed as a result, and when the marines withdrew in 1924, life quickly reverted to normal. The Americans bequeathed to Dominicans a keen interest in baseball. The domineering presence of outsiders certain of their superiority also created a nascent sense of Dominican nationalism. Perhaps the main result of the occupation, an unintended consequence, was that the Guardia Nacional established to assist in upholding order would become the means by which Rafael Trujillo maintained a brutal dictatorship for thirty-one years.32

In Haiti, the marines also encountered stubborn resistance, making it impossible for Wilson to remove them when he was so inclined in 1919. The United States systematically eliminated German economic interests and gained even tighter control over Haiti's finances and customs than it had of the Dominican Republic's. But it could not attract much investment capital, and the country remained impoverished. There was no pretense of democracy: Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels was jokingly called "Josephus the First—King of Haiti." The U.S. financial adviser employed the threat of not paying the salaries of Haitian officials to gain veto power over legislation. The racism of occupying forces was even more acute where the people were stereotyped like African Americans—"the same happy, idle, irresponsible people we know," as a marine colonel put it. United States officials imposed the Jim Crow style of segregation already in place in the American South. They promoted a Tuskegee-type educational system emphasizing technical education and manual labor. Once the marines left, as in the Dominican Republic, the roads (built with forced labor) fell into disrepair and public health programs languished. The blatant racism of the occupation forces pushed a local elite in search of its identity to look back to its African roots.33

Wilson's problems in Central America paled compared to the challenges posed by Mexico. The most profound social movement in Latin American history, the Mexican Revolution was extremely complex, a rebellion of middle and lower classes against a deeply entrenched old order and the foreigners who dominated the nation's economy followed by an extended civil war. It would be six years before the situation stabilized. The ongoing struggle created major difficulties for Wilson. His well-intentioned if misguided meddling produced two military interventions in three years and nearly caused an unnecessary and possibly disastrous war. The best that can be said is that he kept the interventions under tight control and learned from his Mexican misadventures something of the limits of America's appeal to other nations and its power to effect change there.

For thirty-one years, Porfirio Díaz had maintained an open door for foreign investors. Under his welcoming policies, outsiders came to own three-fourths of all corporations and vast tracts of land—newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst alone held some seven million hectares in northern Mexico. United States bankers held Mexican bonds. British and U.S. corporations controlled 90 percent of Mexico's mineral wealth and all its railroads and dominated its oil industry. Díaz hoped to promote modernization and economic development, but the progress came at enormous cost. Centralization of political control at the expense of local autonomy caused widespread unrest, especially in the northern provinces, provoking growing anger toward the regime and its foreign backers. Foreigners used Mexican lands to produce cash crops for export, disrupting the traditional economy and village culture and leaving many peasants landless. Mexican critics warned of a "peaceful invasion." Díaz's policies, they charged, made their nation a "mother to foreigners and a stepmother to her own children."34 Mexico's economy was at the mercy of external forces, and a major recession in the United States helped trigger revolution. In 1910, middle and lower classes under the leadership of Francisco Madero rose up against the regime. In May 1911, they overthrew Díaz.

Counterrevolutions quickly followed. Madero instituted a parliamentary democracy but maintained the status quo economically, disappointing many of his backers. Díaz's supporters plotted to regain power. In his last years in office, Díaz had balanced rising U.S. power in Mexico by encouraging European and especially British economic and political influence. When Madero sustained this policy, U.S. businessmen who at first welcomed the revolution turned against him. They gained active support from Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, a conservative career diplomat friendly to U.S. business interests and skeptical of the revolution. A heavy drinker, something of a loose cannon, and meddlesome in the worst tradition of Joel Poinsett and Anthony Butler, Wilson sought to undermine official support for Madero and sympathized with plots to get rid of him.General Victoriana Huerta overthrew the government in February 1913 and brutally murdered Madero and his vice president. Out of negligence and indifference, Ambassador Wilson bore some responsibility for this gruesome outcome. Madero's corpse was scarcely in the grave when his supporters launched a civil war against Huerta.35

In one of his first ventures in diplomacy, President Wilson set a new subjective standard for recognizing revolutionary governments. Responding to the French Revolution, Thomas Jefferson had established the precedent of recognizing any government formed by the will of the nation. The United States traditionally had recognized governments based simply on whether they held power and fulfilled their international obligations. With Mexico, Wilson introduced a moral and political test. Huerta was indeed a despicable character, crude, corrupt, cruel, "an ape-like man" who "may be said almost to subsist on alcohol," a presidential confidant reported.36 Wilson was appalled by the murder of Madero and indignantly vowed that he would not "recognize a government of butchers." He also suspected Huerta's ties to U.S. and especially foreign businessmen. In view of the importance of the Panama Canal, he told the British ambassador, it was vital for Central American nations to have "fairly decent rulers." He "wanted to teach those countries a lesson by insisting on the removal of Huerta."37 He hoped, in his own pretentious and oftquoted words, to teach U.S. neighbors to "elect good men." Aware that recognition might cripple the opposition, he withheld it in hopes of bringing to power a more respectable government. In so doing, he created yet another instrument to influence the internal politics of Latin American nations.38

Wilson also dispatched two trusted personal emissaries to Mexico to push for a change of government. Neither was up to the task. William Bayard Hale was a journalist and close friend; John Lind, a Minnesota politician. Neither spoke Spanish or knew anything about Mexico; Lind indeed considered Mexicans "more like children than men" and claimed they had "no standards politically."39 Their mission—to counsel Mexico "for her own good," in Wilson's patronizing words—was a fool's errand. They were to persuade Huerta to hold elections in which he would not run and all parties would abide by the result. The president authorized Lind to threaten the stick of military intervention and dangle the carrot of loans before those Mexican leaders who went along.

Predictably, the ploy failed. The crafty Huerta dodged, feinted, and parried. At first flatly rejecting proposals he deemed "hardly admissible even in a treaty of peace after a victory," he then appeared to acquiesce, promising to give up the presidency and hold elections in late October.40 After a series of military defeats, however, he arrested most of the congress and in what amounted to a coup d'état established a dictatorship. Huerta's opposition responded no more positively to U.S. interference. Constitutionalist "First Chief" Venustiano Carranza expressed resentment at Wilson's intrusion and angrily insisted that he would not participate in a U.S.-sponsored election.

Admitting to a "sneaking admiration" for Huerta's "indomitable, dogged determination," Wilson stepped up the pressure.41 He blamed the British for Huerta's intransigence and combined stern public warnings with soothing private explanations of U.S. policy. He seriously considered a blockade and declaration of war, again claiming it to be his "duty to force Huerta's retirement, peaceably if possible but forcibly if necessary."42 Ultimately, he contented himself with measures short of war, warning the Europeans to stay out, sending a squadron of warships to Mexico's east coast, and lifting an arms embargo to help Carranza militarily.

If Wilson was looking for a pretext for military intervention, he got it at Tampico in April 1914 when local officials mistakenly arrested and briefly detained a contingent of U.S. sailors who had gone ashore for provisions. The officials quickly released the captives and expressed regret, but the imperious U.S. admiral on the scene demanded a formal apology and a twenty-one-gun salute. A Gilbert and Sullivan incident escalated into full-scale crisis. Undoubtedly seeking to gain diplomatic leverage, Wilson fully backed his admiral. Huerta at first rejected U.S. demands. Sensing an opportunity for gainful mischief, he then cleverly proposed a simultaneous salute and next a reciprocal one. Wilson rejected both; Huerta rebuffed America's "unconditional demands."43

Seizing what he called a "psychological moment," Wilson ordered a military intervention at Veracruz to promote his broader goal of getting rid of Huerta.44 He pitched his actions on grounds of defending national honor. He easily secured congressional authorization to use military forces, although some hotheads, including his future archenemy, Republican senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, preferred all-out war, military occupation of Mexico, and even a protectorate. To demonstrate his good intentions, the president recruited veterans from Philippine nation-building to show the Mexicans and others through the U.S. occupation the values of progressive government. "If Mexico understood that our motives were unselfish," Colonel House affirmed, "she should not object to our helping adjust her unruly household."45

It was a very big "if," of course. For the short term, at least, the intervention failed on all counts. Instead of welcoming the North Americans as liberators, Mexicans of varied political persuasions rallied to the banner of nationalism. In Veracruz, civilians, prisoners quickly released from jails, and soldiers acting on their own fiercely resisted the invasion. It took two days to subdue the city. More than two hundred Mexicans were killed, nineteen Americans. Across Mexico, newspapers cried out for "Vengeance! Vengeance! Vengeance!" against the "pigs of Yanquilandia." In several cities, angry mobs attacked U.S. consulates. Even Carranza demanded U.S. withdrawal.46

United States forces took control of the city in early May, remained there for seven months, and performed numerous good works—with ephemeral results. The military government implemented progressive reforms to show Mexicans by "daily example" that the United States had come "not to conquer them, but to help restore peace and order." Occupation troops built roads and drainage ditches; provided electric lighting for streets and public buildings; reopened schools; cracked down on youth crime, gambling, and prostitution; made tax and customs collection more equitable, efficient, and lucrative for the government; and developed sanitation and public health programs to transform a beautiful but filthy city into "the cleanest town in the Republic of Mexico." As in the Dominican Republic and Haiti, within weeks after the marines left it was hard to tell that Americans had been in Veracruz.47

The intervention contributed only indirectly to the removal of Huerta. At first, the dictator used the U.S. presence to rally nationalist support. Shaken by Mexican resistance, saddened by the loss of life, and increasingly fearful of a Mexican quagmire, Wilson as a face-saving gesture accepted in July a proposal from Argentina, Brazil, and Chile to mediate. While Wilson and Huerta's representatives quickly deadlocked in the surreal and inconclusive talks at Niagara Falls, New York, the civil war intensified. Now able to secure arms, Carranza's forces steadily gained ground and in mid-1914 forced Huerta to capitulate. Chastened by the experience, Wilson confided to his secretary of war that there were "no conceivable circumstances which would make it right for us to direct by force or by threat of force the internal processes of a revolution as profound as that which occurred in France."48 In November 1914, with Carranza firmly in power, the president removed the occupation forces.

A year of relative quiet followed. In Mexico itself, the civil war raged on, rival factions under populist leaders Emiliano Zapata in the south and Francisco "Pancho" Villa in the north challenging Carranza's fragile government. To promote order and perhaps a government he could influence, Wilson tried to mediate among the warring factions, issuing at least a veiled threat of military intervention if they refused. Carranza and Zapata flatly rejected the overture. Villa's fortunes were obviously declining, and he appeared receptive, opening a brief—and fateful—flirtation with the United States. Carranza continued to gain ground militarily, however. Increasingly preoccupied with the European war, having just weathered the first U-boat crisis with Germany, and fearful of growing German intrigue in Mexico, Wilson did an abrupt about-face. Even though he considered Carranza a "fool" and never established the sort of paternalistic relationship he sought, he reluctantly recognized the first chief's government. He even permitted Carranza's troops to cross U.S. territory to attack the Villistas.49

Villa quickly responded. To the end of 1915, he had seemed among various Mexican leaders the most amenable to U.S. influence. A sharecropper and cattle rustler before becoming a rebel, the colorful leader was a strange mixture of rebel and caudillo.50 At first viewed by Wilson and other Americans as a dedicated social reformer, a kind of Robin Hood, he sought to secure arms and money by showing restraint toward U.S. interests in areas he controlled. He refused even to protest the occupation of Veracruz. As his military and financial position worsened, however, he began to tax U.S. companies more heavily. Several major military defeats in late 1915 and Wilson's seeming betrayal caused him to suspect—incorrectly—that Carranza had made a sordid deal with Wilson to stay in power in return for making Mexico an American protectorate.51

Denouncing the "sale of our country by the traitor Carranza" and claiming that Mexicans had become "vassals of an evangelizing professor," Villa struck back.52 He began to confiscate U.S. property, including Hearst's ranch. In January 1916, his troops stopped a train in northern Mexico and executed seventeen American engineers. Even more boldly, he decided to attack the Americans "in their own den" to let them know, he informed Zapata, that Mexico was a "tomb for thrones, crowns, and traitors."53 On March 9, 1916, to shouts of "Viva Villa" and "Viva México," five hundred of his troops attacked the border town of Columbus, New Mexico. They were driven back by U.S. Army forces after a six-hour fight in which seventeen Americans and a hundred Mexicans were killed. Villa hoped to put Carranza in a bind. If the first chief permitted the Americans to retaliate by invading Mexico, he would be exposed as a U.S. stooge. Conflict between Carranza and the United States, on the other hand, might permit Villa, by defending the independence of his country, to promote his own political ambitions.54

Wilson had little choice but to respond forcibly. He may have feared that Villa's actions would have a domino effect throughout Central America in a time of rising international tension. In the United States, hotheads who had demanded all-out intervention since 1914, including oilmen, Hearst, and Roman Catholic leaders, grew louder. This first attack on U.S. soil since 1814 provoked angry cries for revenge that took on greater significance in an election year. Wilson may also have seen a firm response to Villa's raid as a means to promote his plans for reasonable military preparedness and strengthen his hand in dealing with European belligerents. He quickly put together a "punitive expedition" of more than 5,800 men (eventually increased to more than 10,000), under the command of Gen. John J. Pershing, to invade Mexico, capture Villa, and destroy his forces. United States troops crossed the border on March 15.55

The expedition brought two close, yet distant, neighbors to the brink of an unwanted and potentially disastrous war. Pershing's forces eventually drove 350 miles into Mexico. Even with such modern equipment as reconnaissance aircraft and Harley-Davidson motorcycles, they never caught a glimpse of the elusive Villa or engaged his troops in battle. Complaining that he was looking for a "needle in a haystack," a frustrated Pershing urged occupation of part or all of Mexico. All the while Villa's army, now estimated at more than ten thousand men, used hit-and-run guerrilla tactics to harass U.S. forces and seize northern Mexican cities. On one occasion, Villa reentered the United States, striking the Texas town of Glen Springs.56

Although Wilson had promised "scrupulous respect" for Mexican sovereignty, as Pershing drove south tensions with Carranza's government inevitably increased. Mexican and U.S. forces first clashed at Parral. On June 20, a U.S. patrol engaged Mexican troops at Carrizal. Americans at first viewed the incident as an unprovoked attack and demanded war. Wilson responded by drafting a message for Congress requesting authority to occupy all Mexico. Now embroiled in yet another dangerous submarine crisis with Germany, he also mobilized the National Guard and dispatched thirty thousand troops to the Mexican border, the largest deployment of U.S. military forces since the Civil War.

Cooler heads ultimately prevailed. Peace organizations in the United States, including the Women's Peace Party, pushed Wilson for restraint, and when they publicized evidence that Americans had fired first at Carrizal, he hesitated. Carranza's freeing of U.S. prisoners helped ease tensions. Wilson admitted shame over America's first conflict with Mexico in 1846 and had no desire for another "predatory war." He suspected that it would take more than five hundred thousand troops to "pacify" Mexico. He did not want one hand tied behind his back when war with Germany seemed possible if not indeed likely.57 "My heart is for peace," he told activist Jane Addams. In a speech on June 30, 1916, he eloquently asked: "Do you think that any act of violence by a powerful nation like this against a weak and distracted neighbor would reflect distinction upon the annals of the United States?" The audience resoundingly answered "No!"58 After six months of tortuous negotiations with Mexico, the punitive expedition withdrew in January 1917, just as Germany announced the resumption of U-boat warfare.

Wilson's firm but measured response helped get military preparedness legislation through Congress in 1916, strengthened his hand with Germany during yet another U-boat crisis, and aided his reelection in November. Mobilization of the National Guard and the training received by the army facilitated U.S. preparations for war the following year.59 On the other hand, the failed effort to capture Villa left a deep residue of ill will in Mexico. Only recently dismissed as a loser, the elusive rebel joined the pantheon of national heroes as the "man who attacked the United States and got away with it."60 Carranza moved closer to Germany, encouraging Berlin to explore with Mexico the possibility of an anti-American alliance.

Wilson's Mexican policy has been harshly and rightly criticized. More than most Americans, he accepted the legitimacy and grasped the dynamics of the Mexican Revolution. He deeply sympathized with the "submerged eighty-five percent of the people . . . who are struggling towards liberty."61 At times, he seemed to comprehend the limits of U.S. military power to reshape Mexico in its own image and the necessity for Mexicans to solve their own problems. But he could not entirely shed his conviction that the American way was the right way and he could assist Mexico to find it. He could never fully understand that those Mexicans who shared his goals would consider unacceptable even modest U.S. efforts to influence their revolution. Conceding Wilson's good intentions, his actions were often counterproductive. He averted greater disaster mainly because in 1914 and again in 1916 he resisted demands for occupation, even the establishment of a protectorate, and declined to prolong fruitless interventions.62

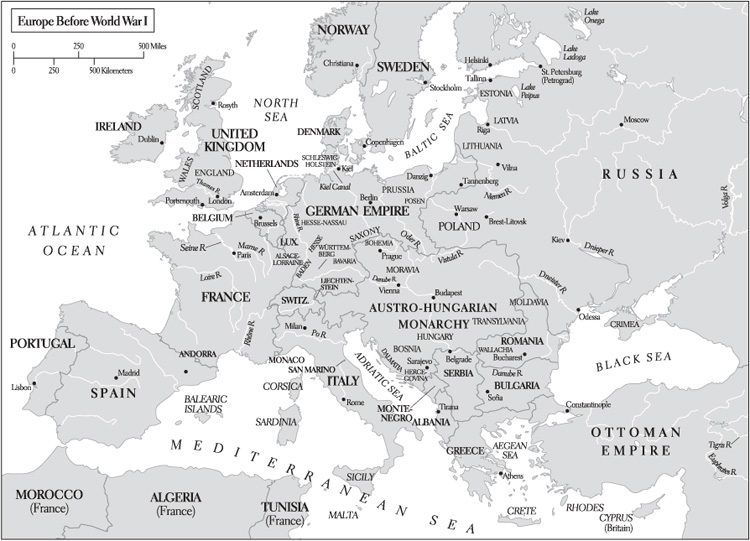

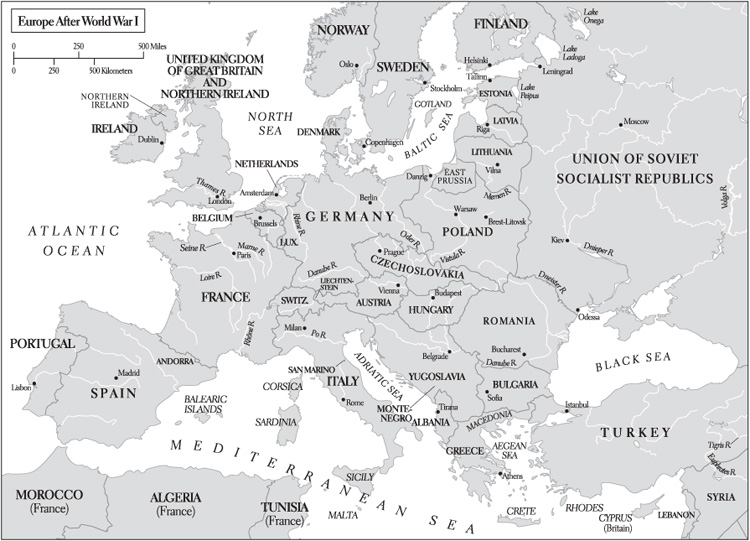

If Mexico, by Wilson's admission, was a thorn in his side, the Great War was far more, dominating his presidency and eventually destroying him, politically and even physically. On the surface, Europe seemed peaceful in the summer of 1914. In fact, a century of relative harmony was about to end. For years, the great powers felt increasingly threatened by each other, their fears and suspicions manifested in a complex and rigid system of alliances, an arms race intended to gain security through military and naval superiority, and war plans designed to secure an early advantage. Unstable domestic political environments in Germany and Russia cleared the path to war. When a Serbian nationalist assassinated the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, in Sarajevo in June, what might have remained an isolated incident escalated to war. Its honor affronted, Austria-Hungary gained German support and set out to punish Serbia. Russia responded by mobilizing behind its Serbian ally, an act designed to deter Germany that instead provoked a declaration of war. Britain joined Russia's ally France in war against Germany. None of the great powers claimed to want war, but their actions produced that result. Expecting a short and decisive conflict, Europeans responded with relief and even celebration. Young men marched off to cheering crowds with no idea of the horrors that awaited them.63

The conflict that began in August 1914 defied all expectations. Technological advances in artillery and machine guns and an alliance system that encouraged nations facing defeat to hang on in expectation of outside support ensured that the war would not be short and decisive. The industrial revolution and the capacity of the modern nation-state to mobilize vast human and material resources produced unprecedented destructiveness and cost. Striking quickly, Germany drove to within thirty miles of Paris, reviving memories of its easy victory in 1870–71. This time French lines held. An Allied counteroffensive pushed the Germans back to France's eastern boundary, where they dug into heavily fortified entrenchments. By November 1914, opposing armies faced each other along a 475-mile front from the North Sea to the Swiss border. The combatants had already incurred staggering costs—France's battle deaths alone exceeded three hundred thousand, and its losses from dead, wounded, or missing surpassed nine hundred thousand. Despite huge casualties on both sides, the lines would not move significantly until March 1917. These first months destroyed any illusions of a quick end and introduced the grim realities of modern combat.64

Conditioned by more than a century of non-involvement in Europe's quarrels, Americans were shocked by the guns of August. The outbreak of war "came to most of us as lightning out of a clear sky," one thoughtful commentator wrote. They also expressed relief to be remote from the conflict. "Again and ever I thank God for the Atlantic Ocean," the U.S. ambassador in Great Britain exclaimed.65 Americans were not without their prejudices. More than one-third of the nation's citizens were foreign born or had one parent who was born abroad. A majority, including much of the elite, favored the Allies because of cultural ties and a belief that Britain and France stood for the right principles. German Americans, on the other hand, naturally supported the Central Powers, as did Irish Americans who despised Britain, and Jewish and Scandinavian Americans who hated Russia. "We have to be neutral," Wilson observed in 1914, "since otherwise our mixed populations would wage war on each other."66

Whatever their preferences, the great majority of Americans saw no direct stake in the struggle and applauded Wilson's proclamation that their country be "neutral in fact as well as in name . . . , impartial in thought as well as in action." Indeed, in terms of the nation's long tradition of non-involvement in Europe's wars, the seeming remoteness of the conflict, and the advantages of trading with both sides, neutrality appeared the obvious course. The president even wrote a brief message to be displayed in movie theaters urging audiences "in the interest of neutrality" not to express approval or disapproval when war scenes appeared on the screen. From the outset, Wilson also saw in the war a God-given opportunity for U.S. leadership toward a new world order. "Providence has deeper plans than we could possibly have laid ourselves," he wrote House in August 1914.67

As a neutral, the United States could provide relief assistance to wartorn areas, and its people responded generously. The American Red Cross shipped supplies worth $1.5 million to needy civilians; its hospital units cared for the wounded.68 Belgian relief was one of the great humanitarian success stories of the war. Headed by mining engineer and humanitarian Herbert Hoover, the program found ingenious ways to get around the German occupation and the British blockade to save the people of Belgium. Admiringly called a "piratical state organized for benevolence," Hoover's Commission for Belgian Relief had its own flag and cut deals with belligerents to facilitate its work. It raised funds from citizens and governments across the world, $6 million from Americans in cash, more than $28 million in kind. The commission bought food from many countries, arranged for its shipment, and, with the help of forty thousand Belgian volunteers, got it distributed. It spent close to $1 billion, fed more than nine million people a day, and kept a nation from starving. Known as the "Napoleon of mercy" for his organizational and leadership skills, Hoover became an international celebrity.69

The implementation of neutrality policy posed much greater challenges. It had been very difficult a century earlier for a much weaker United States to remain disentangled from the Napoleonic wars. America's emergence as a major power made it all the more problematical. Emotional and cultural ties to the belligerents limited impartiality of thought. Wilson and most of his top advisers, except for Bryan, favored the Allies. The United States' latent military power made it a possibly decisive factor in the conflict. Most important, its close economic ties with Europe and especially the Allies severely restricted its ability to remain uninvolved. At the outbreak of war, exports to Europe totaled $900 million and funded the annual debt to European creditors. Some Americans saw war orders opening a further expansion of foreign trade. At the very least, maintaining existing levels was an essential national interest. That this might be incompatible with strict neutrality was not evident at the beginning of the war. It would become one of the great dilemmas of the U.S. response.

In reality, trade was so important to Europe and the United States itself that whatever Americans did or did not do would have an important impact on the war and the domestic economy. Attempts to trade with one set of belligerents could provoke reprisals from the other; trading with both, as in Jefferson and Madison's day, might result in retaliation from each. A willingness to abandon trade with Europe might have ensured U.S. neutrality, but it would also have entailed unacceptable sacrifices to a nation still reeling from an economic downturn. The United States could not remain unaffected, nor could it maintain an absolute, impartial neutrality.

Although legally and technically correct, Wilson's neutrality policy favored the Allies. Seeking to establish the "true spirit" of neutrality, Bryan, while the president was absent from Washington mourning the death of his wife, imposed a ban on loans to belligerents on the grounds that money was the worst kind of contraband. The consequences quickly became obvious. The Allies desperately needed to purchase supplies in the United States and soon ran out of cash. Bryan's strict neutrality thus threatened the Allied cause and U.S. commerce. Drawing a sharp distinction between public loans, by which U.S. citizens would finance the war with their savings, and credits that would permit Allied purchases and avoid "the clumsy and impractical method of cash payments," Wilson modified the ruling in October 1914.70 In the next six months, U.S. bankers extended $80 million in credits to the Allies. A year later, the president lifted the ban on loans entirely. Wilson correctly argued that loans to belligerents had never been considered a violation of neutrality. The result, House candidly admitted in the spring of 1915, was that the United States was "bound up more or less" in Allied success.71

Far more difficult to explain, Wilson also acquiesced in Britain's blockade of northern Europe. Employing sea power in a manner sanctioned by its gloried naval tradition, Britain set out to strangle the enemy economically, seeking to keep neutral shipping from entering north European ports and threatening to seize contraband. British officials used precedents set by the Union in the Civil War. Sensitive to history, they also applied the blockade in ways that minimized friction with the United States. In marked contrast to Jefferson and Madison, Wilson acquiesced, an "astonishing concession" of neutral rights, in the words of a sympathetic biographer.72 His position may have reflected his pro-Allied sympathies. More likely, he perceived that, in part because of the British blockade, U.S. trade with Germany was not important enough to make a fuss over. His acquiescence reflected a pragmatic response to a situation he realized the United States could not change. A historian himself, at the start of the war he appears mostly to have feared drifting into conflict with England over neutral rights like his fellow "Princeton man" James Madison a century before.73 He worried that getting drawn into the war might compromise his role as a potential peacemaker. He informed Bryan in March 1915 that arguing with Britain over the blockade would be a "waste of time." The United States should simply assert its position on neutral rights and in "friendly language" inform London that it would be held responsible for violations.74 Acceptance of the blockade tied the United States closer to the Allied cause. It also encouraged British infringements on U.S. neutral rights, leading to major problems in 1916.

By contrast, Wilson took a firm stand against the U-boat, Germany's answer to the British blockade. In February 1915, Berlin launched a submarine campaign around the British Isles and warned that neutral shipping might be affected. Wilson responded firmly but vaguely by holding the Germans to "strict accountability" for any damage done to Americans. A hint of future crises came in March 1915 when a U.S. citizen was killed in the sinking of the British freighter Falaba, an incident Wilson privately denounced as an "unquestionable violation of the just rules of international law with regard to unarmed vessels at sea."75

On May 7, 1915, a U-boat lurking off the southern coast of Ireland sent to the bottom in eighteen minutes the British luxury liner Lusitania, taking the lives of twelve hundred civilians, ninety-four of them children (including thirty-five babies), from injuries, hypothermia, and drowning. Bodies of victims floated up on the Irish coast for weeks. One hundred and twenty-eight U.S. citizens died. The sinking of the Lusitania had an enormous impact in the United States, becoming one of those signal moments about which people later remember where they were and what they were doing. It stunned the United States out of its complacency and brought the Great War home to its people for the first time. It propelled foreign policy to the forefront of American attention.76 Some U.S. citizens expressed great moral outrage at this "murder on the high seas." Ex-president Theodore Roosevelt condemned German "piracy" and demanded war. After days of hesitation and a careful weighing of the alternatives, Wilson dispatched to Berlin a firm note reasserting the right of Americans to travel on passenger ships, condemning submarine warfare in the name of the "sacred principles of justice and humanity," and warning that further sinkings would be regarded as "deliberately unfriendly."77

Wilson's strong stand derived from a rising fear of Germany and especially from concern for his own and his nation's credibility. Suspicion of Germany had grown steadily in the United States since the turn of the century, especially with regard to its hostile intentions in the Western Hemisphere. German atrocities in neutral Belgium, exaggerated by British propaganda, their crude and shocking efforts to bomb civilians from the air, and rumors, sometimes fed by top Berlin officials, of plans to foment rebellion within the United States provoked fear and anger among Americans, the president included. U-boat warfare further called into question basic German decency. The submarine had not been used extensively or effectively in warfare prior to 1915. This new and seemingly horrible weapon violated traditional rules of naval warfare that spared civilians. It killed innocent people—even neutrals—without warning. Britain could compensate U.S. merchants for property seized or destroyed, but lives taken by submarines could not be restored. Most Americans held to what Wilson called a "double wish." They did not want war, but neither did they want to remain silent in the face of such a brutal assault on human life. Republicans appeared ready to exploit the sinking of the Lusitania if the president did not uphold the nation's rights and honor. Wilson also did not want war, but he recognized that to do nothing would sacrifice principles he held dear and seriously damage his stature at home and abroad.78

Wilson's tough line on the Lusitania provoked crises in Washington and Berlin. Still committed to a strict neutrality, no matter the cost, Bryan insisted that Americans must be warned against traveling on belligerent ships. Protests against U-boat warfare must be matched by equally firm remonstrances against British violations of U.S. neutral rights. When Wilson rejected his arguments, the secretary resigned as an act of conscience, removing an important dissenting voice from the cabinet. The Germans also claimed that equity required U.S. protests against a blockade that starved European children. They insisted, correctly as it turned out, that the Lusitania had been carrying munitions. Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg nevertheless recognized that it was more important to keep the United States out of the war than to use submarines without restriction. When a U-boat sank the British ship Arabic in August, killing forty-four, two Americans included, Wilson extracted from Berlin a public pledge to refrain from attacks without warning on passenger vessels and a commitment to arbitrate the Lusitania and Arabic cases. The president weathered his first crisis with Germany, but only because of decisions made in Berlin. He perceived that at some future date Germany could force on him a painful choice between upholding U.S. honor and going to war.79

After a respite of nearly a year, Wilson in the spring and summer of 1916 faced neutrality crises with both Germany and Britain. On March 24, 1916, a U-boat torpedoed the British channel packet Sussex, killing eighty passengers and injuring four Americans. Following a month's delay, the president and Robert Lansing, Bryan's successor as secretary of state, sternly responded that Germany must stop submarine warfare or the United States would break diplomatic relations, a step generally recognized as preliminary to war. After a brief debate, Berlin again found it expedient to accommodate the United States. Bethmann-Hollweg's Sussex pledge of early May promised no further surprise attacks on passenger liners. Wilson won a great victory, but in doing so he further narrowed his choices. Should German leaders decide that use of the U-boat was more important than keeping the United States out of war, he would face the grim choice of submission or breaking relations and possibly war. The United States' neutrality hung on a slender thread.80

In the meantime, tensions with Britain increased sharply. A crisis had been averted the previous year when London after declaring cotton contraband bought enough of the U.S. crop to sustain prices at an acceptable level. Britain's brutal suppression of the Irish Easter Rebellion in the spring of 1916 and especially the execution of its leaders inflamed American opinion, even among many people normally sympathetic to the Allies. In the summer of 1916, the Allies tightened restrictions against neutral ships and seized and opened mail on the high seas. In July, London blacklisted more than eighty U.S. businesses charged with trading with the Central Powers, thereby preventing Allied firms from dealing with them. Wilson privately fumed about Britain's "altogether indefensible" actions, threatened to take as firm a position with London as with Berlin, and denounced the blacklist as the "last straw." Meanwhile, U.S. bankers financed Britain at a level of about $10 million a day. Britain bought more than $83 million of U.S. goods per week, leaving the nation more closely than ever tied to the Allied cause.81

The neutrality crises provoked sweeping reassessments of the most basic principles of U.S. defense and foreign policies. In 1915–16, Americans heatedly debated the adequacy of their military preparedness, the first time since the 1790s that national security concerns had assumed such prominence in U.S. political discourse.82 Preparedness advocates, many of them eastern Republicans representing the great financial and industrial interests, insisted that America's defenses were inadequate for a new and dangerous age. Claiming that military training would also Americanize new immigrants and toughen the nation's youth, they pushed for expansion of the army and navy. They promoted their cause with parades, books, and scare films such as Battle Cry for Peace, which portrayed in the most graphic fashion an invasion of New York City by enemy troops unnamed but easily identifiable as German by their spiked helmets.

On the other side, pacifists, social reformers, and southern and midwestern agrarians denounced preparedness as a scheme to fatten the pockets of big business and fasten militarism on the nation. They professed to favor "real defense against real dangers, but not a preposterous 'preparedness' against hypothetical dangers." They warned that the programs being considered would be a giant step toward war.83 Popular songs such as "I Didn't Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier" expressed their sentiments. The divisions were reflected in Congress, where by early 1916 Wilson's proposals for "reasonable" increases in the armed services were mired in controversy.

Fearful that America might be drawn into war and facing reelection, Wilson in 1916 belatedly assumed leadership of a cause he had previously spurned, breaking one of the most difficult legislative logjams of his first term. To build support for his program, he went on a speaking tour of the Northeast and Middle West, seeking to educate the nation to the dangers posed by a world at war. To thunderous ovations, he called for increased military expenditures—even at one point for "incomparably the greatest navy in the world." Returning to Washington, he skillfully steered legislation through a divided Congress. "No man ought to say to any legislative body 'You must take my plan or none at all,' " he proclaimed on one occasion, a striking statement given the stand he would take on the League of Nations in 1919. The National Defense Act of June 1916 increased the regular army to 223,000 over a five-year period. It strengthened the National Guard to 450,000 men and tightened federal controls. A Naval Expansion Act established a three-year construction program including four dreadnought battleships and eight cruisers the first year. Ardent preparedness advocates such as Theodore Roosevelt dismissed Wilson's program as "flintlock legislation," measures more appropriate for the eighteenth century than for the twentieth. "The United States today becomes the most militaristic naval nation on earth," critics screamed from the other extreme. In fact, Wilson's compromise perfectly suited the national mood and significantly expanded U.S. military power. A remarkably progressive revenue act appeased leftist critics by shifting almost the entire burden to the wealthy with a surtax and estate tax.84

The Great War also sparked a debate over basic foreign policy principles that would rage until World War II and persist in modified form thereafter. Breaking with hallowed tradition, those who came to be called internationalists insisted that the American way of life could be preserved only through active, permanent involvement in world politics. Conservative internationalists such as former president William Howard Taft and senior statesman Elihu Root, mostly Republicans and upper-class men of influence, had long promoted international law and arbitration. In response to the war, they embraced still vague notions of collective security. Generally pro-Allied, they saw defeat of Germany as an essential first step toward a new world order. In June 1915, during the Lusitania crisis, Taft announced formation of a League to Enforce Peace to promote the creation of a world parliament, of which the United States would be a member, that would modify international law and use arbitration to resolve disputes. The conservatives also supported a buildup of U.S. military power and its use to protect the nation's vital interests. Progressive internationalists, on the other hand, fervently insisted that peace was essential to ensure advancement of domestic reforms they held dear: better working conditions for labor; social justice legislation; women's rights. Liberal reformers such as social worker Jane Addams and journalist Oswald Garrison Villard vigorously pushed for ending the Great War by negotiation, eliminating the arms race and economic causes of war, compulsory arbitration, the use of sanctions to deter and punish aggression, and establishing a "concert of nations" to replace the balance of power.85

In response to the new internationalism, a self-conscious isolationism began to take form, and the word isolationism became firmly implanted in the nation's political vocabulary. Previously, non-involvement in European politics and wars had been a given. But the threat posed by the Great War and the emergence of internationalist sentiment gave rise to an ideology of isolationism, promoted most fervently by Bryan, to preserve America's long-standing tradition of non-involvement as a way of safeguarding the nation's way of life.86

While Democratic Party zealots during the election campaign of 1916 vigorously pushed the slogan "He Kept Us Out of War," Wilson began to articulate an internationalist position and also the revolutionary concept that the United States should assume a leadership position in world affairs. In a June 1916 speech Colonel House described as a "land mark in history," he vowed U.S. willingness to "become a partner in any feasible association of nations" to maintain the peace.87 "We are part of the world," he proclaimed in Omaha in early October; "nothing that concerns the whole world can be indifferent to us." The "great catastrophe" brought about by the war, he added later in the day, compelled Americans to recognize that they lived in a "new age" and must therefore operate "not according to the traditions of the past, but according to the necessities of the present and the prophecies of the future." The United States could no longer refuse to play the "great part in the world which was providentially cut out for her. . . . We have got to serve the world."88

Shortly after his narrow reelection victory over Republican Charles Evans Hughes, a gloomy Wilson, fearing that the United States might be dragged into war, redoubled his efforts to end the European struggle. Twice previously, he had sent House—"my second personality"—on peace missions to Europe. His hands strengthened by reelection, he began to promote a general peace agreement including a major role for the United States. In December 1916, he invited both sides to state their war aims and accept U.S. good offices in negotiating a settlement.

In a dramatic January 22, 1917, address to the Senate, Wilson sketched out his revolutionary ideas for a just peace and a new world order. To the belligerents, he eloquently appealed for a "peace without victory," the only way to ensure that the loser's quest for revenge did not spark another war. In terms of the postwar world, a "community of power" must replace the balance of power, the old order of militarism, and power politics. The equality of nations great and small must be recognized. No nation should impose its authority on another. A new world order must guarantee freedom of the seas, limit armaments, and ensure the right of all peoples to form their own government. Most important, Wilson advocated a "covenant" for an international organization to ensure that "no such catastrophe shall ever overwhelm us again." Speaking to his domestic audience, the president advanced the notion, still heretical to most Americans, that their nation must play a key role in making and sustaining the postwar settlement. Without its participation, he averred, no "covenant of cooperative peace" could "keep the future safe without war." He also stressed to his domestic audience that his proposals accorded with American traditions. The principles of "President Monroe" would become the "doctrine of the world." "These are American principles, American policies . . . ," he concluded in ringing phrases. "They are the principles of mankind and must prevail."89

Wilson's speech was "at once breathtaking in the audacity of its vision of a new world order," historian Robert Zieger has written, "and curiously detached from the bitter realities of Europe's battlefields."90 His efforts to promote negotiations failed. His equating of Allied war aims with those of Germany outraged London and Paris. When the blatantly pro-Allied Lansing sought to repair the damage with an unauthorized public statement, he infuriated Wilson and aroused German suspicions. In any event, by early 1917, none of the belligerents would accept U.S. mediation or a compromise peace. Both sides had suffered horribly in the rat-infested, disease-ridden trenches of Europe—"this vast gruesome contest of systematized destruction," Wilson called it.91 The battles of attrition of 1916 were especially appalling. Britain suffered four hundred thousand casualties in the Somme offensive, sixty thousand in a single day, with no change in its tactical position. Germans called the five-month struggle for Verdun "the sausage grinder"; the French labeled it "the furnace." It cost both sides nearly a million casualties. German and French killed at Verdun together exceeded the total dead for the American Civil War.92 By the end of the year, both sides were exhausted.

As investments of blood and treasure mounted, attitudes hardened. In December 1916, David Lloyd George, who had vowed to fight to a "knock-out," assumed leadership of a coalition government in Britain and responded to Wilson's overture with a list of conditions unacceptable to the Central Powers. The Germans made clear they would state their war aims only at a general conference to which Wilson would not be invited. In the meantime, more ominously, German leaders finally acceded to the navy's argument that with one hundred U-boats now available an all-out submarine campaign could win the war before U.S. intervention had any effect. On January 31, Berlin announced the beginning of unrestricted submarine warfare.93

Wilson faced an awful dilemma. Stunned by these developments, he privately labeled Germany a "madman that should be curbed." But he was loath to go to war. He still believed that a compromise peace through which neither side emerged triumphant would be best calculated to promote a stable postwar world. It would be a "crime," he observed, for the United States to "involve itself in the war to such an extent as to make it impossible to save Europe afterward." In view of his earlier threats, he had no choice but to break relations with Germany, and he did so on February 3. Despite the urging of House and Lansing, he still refused to ask for a declaration of war. He continued to insist that he could have greater influence as a neutral mediator than as a belligerent. He recognized that his nation remained deeply divided and that many Americans opposed going to war. As late as February 25 he charged the war hawks in his cabinet with operating on the outdated principles of the "Code Duello."94

Events drove him to the fateful decision. The infamous Zimmermann Telegram, leaked to the United States by Britain in late February, revealed that Germany had offered Mexico an alliance in return for which it might "reconquer its former territories in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona." The document fanned anti-German sentiment in America and increased Wilson's already pronounced distrust of Berlin.95 In mid-March, U-boats sank three U.S. merchant vessels with the loss of fifteen American lives. For all practical purposes, Germany was at war with the United States. Reluctantly and most painfully, Wilson concluded that war could not be avoided. The Germans had repeatedly and brutally violated American rights on the high seas. A failure to respond after his previous threats would undermine his position abroad and open him to political attack at home. Wilson had long since concluded that the United States must play a central role in the peacemaking. Surrender on the U-boat issue would demonstrate its unworthiness for that role. Germany's own repeated violation of its promises and its intrigues as evidenced in the Zimmermann Telegram made clear to Wilson that it could not be trusted. Only through active intervention, he now rationalized, could U.S. influence be used to establish a just postwar order. War was unpalatable, but at least it would give the United States a voice at the peace table. Otherwise, he told Addams, he could only "call through a crack in the door."96 Moving slowly to allow public opinion to coalesce behind him, Wilson concluded by late March that he must intervene in the war.

On April 2, 1917, the president appeared before packed chambers of Congress to ask for a declaration of war against Germany. In a thirty-six-minute speech, he condemned Germany's "cruel and unmanly" violation of American rights and branded its "wanton and wholesale destruction of the lives of non-combatants" as "warfare against mankind." The United States could not "choose the path of submission," he observed. It must accept the state of war that had "been thrust upon it." He concluded with soaring rhetoric that would echo through the ages. "It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war," he conceded. But "the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have always carried dearest to our hearts, for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own Governments, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free people as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free." As critics have repeatedly emphasized, Wilson set goals beyond the ability of any person or nation to achieve. Perhaps he felt such lofty aims were necessary to rally a still-divided nation to take action unprecedented in its history. He may have aimed so high to justify in his own mind the horrors he knew a war would bring. In any event, he set for himself and his nation an impossible task that would bring great disillusionment.97

Germany's gamble to win the war before the United States intervened in force nearly succeeded. Adhering to the nation's long-standing tradition of non-entanglement and in order to retain maximum diplomatic freedom of action, Wilson and General Pershing insisted that Americans fight separately under their own command rather than being integrated into Allied armies. It took months to raise, equip, and train a U.S. army and then transport it to Europe. A token force of "doughboys" paraded in Paris on July 4, 1917, but it would be more than a year before the United States could throw even minimal weight into the fray. In the meantime, buoyed by promises of future U.S. help, France and Britain launched disastrous summer 1917 offensives. French defeats provoked mutinies that sapped the army's will to fight. Allied setbacks in the west combined with the Bolshevik seizure of power in late 1917 and Russia's subsequent withdrawal from the war gave the Central Powers a momentary edge. Facing serious morale problems at home from the Allied blockade, Germany mounted an end-the-war offensive in the spring of 1918.