"Our international trade relations, though vastly important, are in point of time and necessity secondary to the establishment of a sound national economy," Franklin Delano Roosevelt proclaimed in his March 4, 1933, inaugural address. "I favour as a practical policy the putting of first things first."1 Indeed, in this speech to a nation laid low by economic catastrophe, FDR focused exclusively on domestic programs and appealed to Americans' self-reliance. He devoted but one long, and notably vague, sentence to foreign policy—less than Grover Cleveland in 1885. A clear sign of the times, these observations about national priorities also distinguish the 1930s from the preceding decade. During the 1920s, the United States actively participated in resolving international problems. After 1931, involvement without commitment gave way to a pervasive and deeply emotional unilateralism along with congressional safeguards against intervention in war.

Only toward the end of that tumultuous decade, when the reality of war seemed about to touch the United States directly, did a reluctant nation, led by Roosevelt himself, shift course. The shockingly rapid fall of France to the Nazi blitzkrieg in June 1940 spurred a great transformation in attitudes toward what was now being called national security.2 For the first time since the early republic, many Americans feared that in a world shrunken by air power their safety was threatened by events abroad and concluded that the defense of other nations was vital to their own. The flaming wreckage of the fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, provided a graphic visual image marking the end of one era and the beginning of another.

The major cause of the chaos that was the 1930s was the Great Depression, the economic crisis that gripped the world throughout much of the decade and provided a major stimulus for conflict and war. Faced with a sharp economic downturn after 1931, panicky governments across the world to save themselves took autarkic measures such as raising tariffs and manipulating currencies. In a tightly interconnected world economy, such tactics proved disastrous.3 The collapse of a major Austrian bank in 1931 set off a banking crisis in Germany that in turn dealt a staggering blow to France. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Britain had stepped in to meet economic crises. In the early 1930s, economist Charles Kindelberger has tersely concluded, "the British couldn't and the United States wouldn't."4 In September 1931, an embattled Britain abandoned the gold standard, which the United States had pushed it to adopt in the mid-1920s. Across the industrialized world, banks failed, production fell off drastically, and unemployment rose to unprecedented levels. World trade fell by one-third from 1928 to 1932. The international economy ground to a standstill.

Economic catastrophe set off seismic political shocks, rocking to its foundations the rickety structure of peace cobbled together by the great powers in the 1920s. To cope with a crisis unprecedented in its magnitude, governments abandoned cooperation. Their egocentric efforts to revive their own economies provoked further conflict among potential rivals and erstwhile allies. Even the causes of the depression became an issue of bitter debate, Europeans pointing at the United States, President Herbert Hoover, more accurately, blaming Europe. Economic crisis caused profound and pervasive political unrest. Amidst nervous and increasingly angry publics, extremism replaced moderation, caution gave way to adventurism. Fragile democracies in Spain and Germany gave way to fascist dictatorships. Japan abandoned cooperation with the Western powers for rearmament, militarism, and a quest for regional hegemony. At the very time when the postwar system came under grave challenge, the democracies were least inclined to uphold it. Absorbed in domestic crisis and still haunted by bitter memories of the Great War, they reduced armaments and sought protection through the chimera of appeasement. Divided within itself, at times seemingly on the verge of civil war, France passed to Britain responsibility for upholding the world order. Significantly weakened and without the will to maintain its traditional international position, overextended and unsure of the United States, Britain lurched from "agitation to agitation," in the words of Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, without developing a comprehensive policy.5

The boxing aphorism "The bigger they are, the harder they fall" applies to the U.S. economy in the 1930s. The acknowledged world economic powerhouse in the 1920s, the United States was devastated by the depression. Because its economy was less regulated and therefore more volatile, it had fewer cushions against the shocks. After a brief upturn in 1930, it was driven to rock bottom by the European crisis. The gross national product fell by 50 percent between 1929 and 1932, manufacturing by 25 percent, construction by 78 percent, and investment by a stunning 98 percent. Unemployment soared to 25 percent. With growing hunger and homelessness, traditional American optimism gave way to despair. The internationalism that had competed with more conventional attitudes during the 1920s was replaced by a new isolationism.6

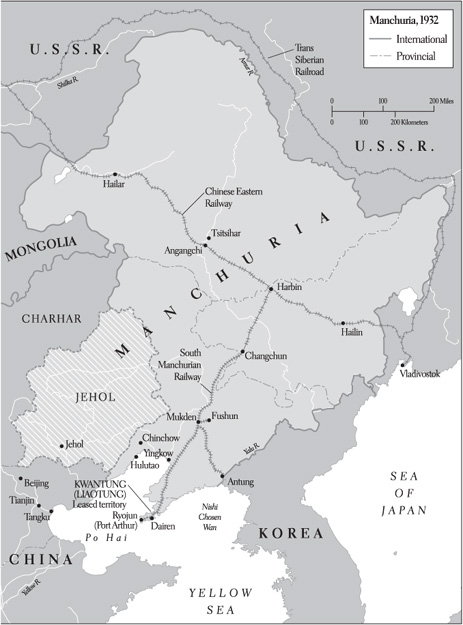

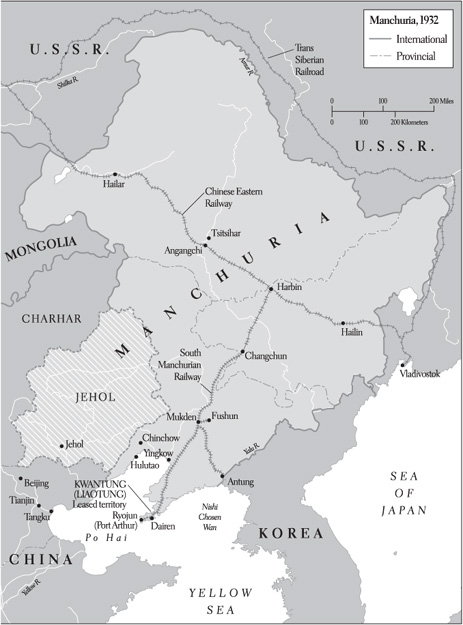

The major trends of international politics in the 1930s were graphically displayed during the Manchurian crisis of 1931–32, the first step on the road back to war. One and one-half times larger than Texas, strategically located between China, Japan, and Russia, Manchuria had been a focal point of great-power conflict in Northeast Asia from the start of the century. Underpopulated, fertile in agricultural output, and rich in raw materials and timber, it drew outside powers like a magnet, especially Japan, whose dreams of national glory required external resources. Manchuria had traditionally been part of China—indeed, the last dynasty had come from there. As Imperial China fell on hard times, however, the great powers increasingly intruded. Conflict over Manchuria helped provoke the 1905 Russo-Japanese War. In 1907 and again in 1910, the two nations divided it into spheres of influence. Shielded by these agreements, Japan established preeminent economic and political power in southern Manchuria.7

Revolutionary China began to challenge outside influence in Manchuria in the late 1920s. Chiang Kai-shek's control over China proper remained tenuous, at best, but he often used attacks on foreign interests to rally domestic support, and Manchuria seemed an especially inviting target. In 1929, Chiang launched a short and ultimately disastrous war against Soviet interests in north Manchuria. Unchastened by defeat, he followed with a less overtly provocative assault against Japan,

encouraging Chinese to emigrate to Manchuria, pushing boycotts of Japanese goods, and urging local warlords to construct a railroad line parallel to the Japanese-controlled South Manchurian Railway.8

Chiang's challenge caused grave concern in Japan. The depression had brought economic catastrophe to the island nation, heightening Manchuria's economic importance. Japan relied on Manchuria for food, many vital raw materials, and about 40 percent of its trade. Although it sought to resolve the mounting difficulties with China by negotiation, even the moderate government then in power viewed Manchuria as essential. The elite officer corps of the Kwantung Army in Manchuria had its own plans. Alarmed at the Chinese challenge and Tokyo's meek response, fearful of losing a major foothold on the Asian mainland, the army saw an opportunity to solidify Japan's position—and its own—in Manchuria, perhaps seize control of the government from the moderates, and implement far-reaching expansionist plans in Asia. The Kwantung Army viewed the international situation as favorable for boldness. The Western powers were preoccupied with the mounting economic crisis; the Soviet Union seemed unlikely to do anything. Thus at Mukden in south Manchuria in September 1931, the army blew up a section of its own railroad, blamed the explosion on the Chinese, and, in a carefully planned and well-executed move, used that incident as pretext to wipe out Chinese resistance in Manchuria.9

The West responded much as the Kwantung Army had anticipated. China's appeals to the League of Nations, the United States, and Great Britain went unheard. At a low point of the depression, the European powers were absorbed in domestic problems, their leaders politically insecure and on the defensive.10 Although Manchuria later took on enormous significance, at the time it seemed no more than marginally important. Indeed, conservative Europeans looked upon the Chinese as scheming and duplicitous and viewed Japan as a source of stability and a bulwark against Communism in northeast Asia. Those few Westerners who viewed with alarm what they saw as Japanese aggression refused to risk a tough stand.

Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson at first contented himself with watchful waiting, viewing the incident as a police action against Chinese dissidents, hoping that Tokyo could control the army, and fearing that a provocative U.S. response might rally the Japanese people to the army. Already at odds with Stimson over other issues, President Hoover adamantly opposed risk-taking. The United States did send a high-level diplomat to participate in Security Council discussions on Manchuria, a significant initiative in itself, but it would go no further. Encouraged by the U.S. response, the League passed a resolution reminding Japan and China of their responsibilities under the Kellogg-Briand Pact, calling for peaceful resolution of the dispute, and asking Japan to withdraw its troops. When this failed, it would do no more than accept Japan's proposal to send an investigatory commission to Manchuria.11

The crisis deepened in late 1931. The Kwantung Army expanded its operations well beyond Mukden, posing a threat to all Manchuria and even North China. The Tokyo government would not or could not stop the onslaught. Wilsonian concepts of collective security called for economic sanctions to stop aggression. Some Europeans and Americans, Stimson included, increasingly viewed Japanese actions as a threat to world order and were willing to go this far. Most Americans saw no vital interests in Manchuria, however, and few sympathized with China. Hoover privately ruminated that it might not be a "bad thing if Mr. Jap should go into Manchuria, for with two thorns in his side—China and the Bolsheviks—he would have enough to keep him busy for awhile." In any event, he adamantly opposed sanctions, which he dismissed as "sticking pins in tigers." He viewed going to war with Japan over Manchuria as "folly."12 Without U.S. backing, the League refused to contemplate sanctions.

Determined to do something but without weapons at his disposal, Stimson in January 1932 resorted to the expedient that became known as the Stimson Doctrine (the first such pronouncement since Tyler). Now certain that Japanese aggression posed a threat to world order, he hoped to use moral sanctions to rally world opinion against Japan. A lawyer by profession, he believed it useful to brand outlaw behavior as such "by putting the situation morally in its right place."13 Taking up an idea first proposed by Hoover, he informed Japan and China that the United States would not recognize territorial changes brought about by force and in violation of the Open Door policy and the Kellogg-Briand Pact. Stimson's doctrine remained a unilateral statement of U.S. policy. Fearing a Japanese threat to their Asian colonies, France and Britain responded ambiguously—and it took London four months to do that. The League gave no more than belated and qualified endorsement.

The Stimson Doctrine had no impact on Japan. By November, the Kwantung Army had moved almost four hundred miles north of Mukden, making clear its determination to take all of Manchuria. The moderate Japanese cabinet fell on December 31, 1931, leaving the government in the hands of men Stimson labeled "virtually mad dogs."14 Shortly after, just as the secretary of state issued his doctrine, fighting extended to Shanghai, a major Chinese port city seven hundred miles south of Manchuria. When a Chinese boycott and mob violence threatened Japanese lives and property, the local Japanese commander dispatched forces to the scene. Eventually, seventy thousand Japanese troops entered Shanghai. Planes and naval vessels bombarded parts of the city, causing extensive civilian casualties and foreshadowing the carnage that would be inflicted on civilians over the next decade. Again, China appealed to the world for help.

Again, Stimson resorted to expedients. Japanese actions were increasingly difficult to justify in terms of defending established interests. The ferocity of the fighting and civilian casualties in Shanghai, widely reported in the Western press, provoked worldwide outrage. But there was only scattered support for strong action. The Western powers remained mired in the depression. The League awaited the report of its investigatory commission. Absorbed in economic problems and facing an election, Hoover did nothing more than beef up U.S. forces to protect the 3,500 Americans in Shanghai. Still persuaded that he must do something but certain that Britain and France would provide no more than "yellow-bellied" support, Stimson fell back on the Nine-Power Pact. In an open letter to Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman William Borah, he charged Japan with violating that agreement, thereby releasing other signatories from their obligations under the Washington Treaties, a thinly veiled—and largely empty—threat that the United States might begin naval rearmament.15

By his own admission, Stimson was armed with nothing more than "spears of straw and swords of ice," and his statement did nothing to stop the Japanese conquest of Manchuria.16 Japan did withdraw its troops from Shanghai—before Stimson released the Borah letter. In the meantime, it solidified its control of Manchuria. Using as a figurehead the last Manchu emperor, the tragic "boy emperor," Henry Pu Yi, the Japanese created in March 1932 the puppet state of Manchukuo. The League commission's report placed some blame on China for provoking the Mukden incident but criticized Japan for using excessive force. It called for non-recognition of Manchukuo and proposed an autonomous Manchuria in which Japan's established rights would be respected. When the League adopted the report in early 1933, the Japanese walked out. Stopping in the United States en route home, delegate Yosuke Matsuoka complained that the West had taught Japan to play poker, gained most of the chips, and then declared the game immoral and changed to contract bridge.17

It has been conventional wisdom since the 1940s that a firm Western response in 1931 would have prevented World War II. The so-called Manchurian/Munich analogy, which preached the necessity of resistance to aggression at the outset, became a stock-in-trade of postwar U.S. foreign policy. To be sure, the paralyzing impact of the depression and the sharp divisions among the Western powers resulted in a weak response. Only the United States did anything, and as both the British and Chinese hastened to point out, Stimson's protests were "only words, words, words, and they amount to nothing if not backed by force."18 But there is no certainty that a firmer response in Manchuria would have prevented subsequent Japanese and German aggression. Nor did the non-response necessarily ensure future war. Neither Japan nor Nazi Germany at this time had a master plan or explicit timetable for expansion. The plain hard truth is that the Western powers in 1931 lacked both the will and the means to stop Japan's conquest of Manchuria. However attractive economic sanctions may seem in retrospect, their track record through history does not inspire confidence. They generally succeed only when the major powers unite behind them, which was assuredly not the case in 1931–32. The Western democracies together could not have brought to bear enough military power to stop Japan. To have gone to war in 1931 might have been more disastrous than a decade later. The crisis was significant less for its destruction of an established order in East Asia than for the stark revelation that there had been no order in the first place. It highlighted the weakness of the League of Nations but did not bring its downfall. Above all, it demonstrated the limits of what diplomacy can do in some crisis situations. 19

Shortly after Japan left the League of Nations, ending the Manchurian crisis, and with the U.S. economy at a standstill, a despondent Hoover gave way to the ebullient Franklin Roosevelt. Raised to old money in the gentile surroundings of New York's Hudson Valley, FDR, as he came to be known, was a middling student at prestigious Groton Academy and Harvard. After a brief and undistinguished fling at the law, he followed his distant cousin Theodore by taking the post of assistant secretary of the navy in the Wilson administration. Stricken with a crippling and life-changing case of polio in the early 1920s, he found his niche in electoral politics, winning the governorship of New York and then soundly defeating the discredited Hoover in 1932.

Roosevelt dominated the tumultuous decade that followed as few presidents have dominated their eras, and only Wilson stands above him in importance in twentieth-century U.S. foreign policy. He was a man of dauntless optimism, a trait that served him and the nation well during years of economic crisis and war. Although he had few close personal friends, he was capable of great warmth and personal charm and possessed formidable political skills. Blessed with a resonant voice and a rare eloquence, he used the new medium of radio to singular advantage in informing, reassuring, and rallying a troubled nation. As a result of the noblesse oblige in which he was raised, religion, and perhaps his struggle with polio, he developed a deep sensitivity to the needs of the less fortunate. He had a rare ability in hard times to articulate the core values of freedom from want and fear. His influence, like that of Wilson, touched millions of people across the world.20

Roosevelt viewed himself as a practical idealist—"I dream dreams," he once said, "but I am an intensely practical man"—and his accomplishments were considerable, but his leadership was not without flaws. He could be frustratingly elusive and enigmatic, confounding contemporaries and historians alike. It remains extremely difficult at any given time to read his mind with any precision on any issue. A notoriously sloppy administrator who knowingly appointed conflicting personalities to competitive positions, he created a multiplicity of agencies with overlapping responsibilities, then watched with seeming glee as they engaged in bitter and at times enervating turf wars. Especially in the area of diplomacy, he made some bizarre and disastrous appointments. He could be bold and brilliantly improvisational. Yet through much of the 1930s, on vital issues of national security he could seem maddeningly timid, perhaps underestimating his powers of persuasion, not acting until events imposed decisions upon him.

Through the 1930s, the making of U.S. foreign policy remained a relatively simple process. The State Department continued to be the key player, although on major issues Roosevelt usually took control and in some areas his close friend Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. played an important role. True to form under FDR, State itself was deeply divided. The secretary, Cordell Hull, remained in office a record twelve years, but his influence was limited. A native of the rugged Cumberland region of Tennessee, "the judge," as he was called, was a political appointee, a veteran congressman, confirmed Wilsonian, and fervent advocate of free trade, useful to FDR mainly in keeping southern congressmen in line. Frailness of body and a benign countenance masked an iron will, a fiercely competitive spirit, and a raging temper. Hull's seething hatreds could set loose a volcanic eruption of profanity, made all the more colorful by a slight speech impediment. The undersecretary after 1937, Sumner Welles, was in many ways Hull's polar opposite. Born to wealth (and then married to more), Welles shared FDR's prep school and Ivy League pedigree. Suave, sophisticated, and snobbish, he was dapper in dress with finely tailored suits and an ivory-handled walking stick. No one "could possibly look so much like a career diplomat," a colleague observed, "bearing, gestures, the way his chin is carried, everything." The fierce rivalry between the two misfits burned throughout much of the Roosevelt era.21

During the long interregnum between Hoover's defeat and Roosevelt's inauguration (new presidents were then inaugurated in March), the United States approached the brink of despair. One-fourth of the workforce was unemployed; relief funds from state and local governments had been exhausted. Farmers had suffered economically since the Great War, and as prices plummeted still further in the 1930s mortgage foreclosures became commonplace. Shanty towns for the homeless—so-called Hoovervilles—took shape in most major cities. In early 1933, a series of bank failures produced runs on the banks by panicky citizens that in turn led to the declaration of banking "holidays" in many states to prevent further failures. While the economic situation deteriorated, Congress did nothing. Hoover stubbornly tried to secure from FDR a commitment to follow his discredited programs. The president-elect wisely refused but left little indication how he might deal with the nation's most serious crisis since the Civil War. The mood of the country was one of deep despondency. "We are in the doldrums," a journalist observed, "waiting not even hopefully for the wind which never comes."22

Conditions abroad were equally grim. Europe continued its economic plunge, and the leading nations could not agree how to stop it. A once "cosmopolitan world order had dissolved into various rivaling subunits," Paul Kennedy has written, "a sterling block, based upon British trade patterns . . .; a gold block, led by France; a yen block dependent upon Japan . . .; a U.S.-led dollar block (after Roosevelt also went off gold); and, completely detached from these convulsions, a USSR steadily building 'socialism in one country.' "23 As always, Germany was especially volatile. In January 1933, in a move whose full significance was not clear at the time, the aged president, Paul von Hindenburg, asked National Socialist leader Adolf Hitler to assume the chancellorship. Hitler would subsequently assume full powers. By the end of the year, he would pull Germany out of the Geneva Disarmament Conference and the League of Nations.

As a vice presidential candidate in 1920, Roosevelt had campaigned vigorously for the League of Nations, but like the nation he too turned sharply inward under the burden of the Great Depression. In 1932, he explicitly spurned his mentor Wilson's handiwork and scoffed at the Hoover moratorium. After assuming the presidency, he further reduced in size an already small army. Like Theodore a naval enthusiast, he built the fleet up only to the limits set by the Washington and London conferences. As his inaugural address suggested, he firmly believed that the depression had domestic roots. He sought nationalist solutions, mainly through inflation.

FDR's handling of the World Economic Conference in London in the summer of 1933 reveals not only his "putting of first things first" but also a cavalier and feckless diplomatic style that would become something of a trademark and in this case would have baneful consequences. During the frantic first Hundred Days of the New Deal, Roosevelt deluged Congress with a flood of domestic legislation attacking the depression from various directions. To make sure international problems did not intrude on his domestic agenda, he delayed the long-proposed conference until June. He made sure that the still-divisive issue of World War I debts stayed off the agenda. He sent to the conference a bizarre assemblage of delegates ranging from the drunken isolationist Senator Key Pittman of Nevada to the Wilsonian internationalist and free trader Hull, virtually ensuring no agreement. As the conference was about to convene, he blithely sailed away for an extended vacation. And when the conferees finally agreed on a plan for international currency stabilization, he fired off to London his infamous "Bombshell Message"—appropriately dispatched from the cruiser USS Indianapolis—making clear his rejection of such schemes and his determination to find economic solutions at home. Roosevelt's salvo ended the conference without any agreement. Published on July 4, 1933, and hailed by some Americans as a second declaration of independence, it destroyed the last vestige of international cooperation in dealing with the worldwide depression.24

Roosevelt has been rightly criticized for his handling of the London conference. Economists disagree in assessing the conference itself, many concluding that currency stabilization would not have worked and that since the domestic market remained the key to U.S. prosperity FDR was right to focus on homegrown solutions. Scholars also agree, however, that he erred by encouraging the conferees to believe he supported their work and Hull to believe that he was committed to tariff reduction. His views toward the deliberations exposed facile national stereotypes: "When you sit around the table with a Britisher," he observed during the deliberations, "he usually gets 80% of the deal and you get what's left."25 FDR later admitted that the rhetoric of his Bombshell Message was overblown and destructive, but at the time he boasted that it might persuade Americans that their country did not always lose in international negotiations. Whatever the economic consequences, of course, the failure of the conference and FDR's role in it had a devastating diplomatic impact, especially on relations with Britain.26

Roosevelt's personal imprint also marked another early foreign policy initiative: recognition of the Soviet Union. The policy of non-recognition had long since become outdated, of course, and the ever pragmatic FDR abandoned it because he believed it served no useful purpose. Hard-core anti-Communists such as patriotic organizations, the Roman Catholic Church, and some labor unions still passionately opposed recognition, but in the depths of the depression it was no longer a hot-button issue. Some Americans, FDR and many business leaders included, hoped that diplomatic relations would bring increased trade. Roosevelt may also have hoped that the mere act of recognition would give pause to expansionists in Germany and Japan.27

Properly wary of State Department hard-liners, Roosevelt centered negotiations in the White House, and over nine days in November 1933 he and Soviet foreign minister Maxim Litvinov hammered out a badly flawed agreement. FDR was sufficiently sensitive to his domestic critics to seek concessions in return for recognition—unusual if not indeed extraordinary in diplomatic practice. The agreement itself took a convoluted form: eleven letters and one memorandum addressing a range of issues. Unsurprisingly, given the vast gulf of culture and ideology that separated the two nations, the negotiations proved difficult. Roosevelt focused on securing diplomatic relations. He gained vague Soviet guarantees of religious freedom for Americans in the USSR and promises to stop Comintern propaganda in the United States. Unable to agree on the crucial issues of possible loans and debts owed by the prerevolutionary governments, the two sides settled for sloppy language that would cause much future wrangling.28

Establishment of diplomatic relations was the only tangible result of the Roosevelt-Litvinov agreements. FDR pleased the Soviets by naming their onetime advocate William C. Bullitt the first U.S. ambassador to Moscow. Bullitt set about his task with customary zeal, in his spare time seeking to teach the Russians baseball and the Red Army cavalry the decidedly unproletarian sport of polo. Plans to construct on the Moscow River a U.S. embassy modeled on Jefferson's Monticello evoked positive responses from FDR and Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin.29 For both nations, the warm glow of expectations quickly gave way to disillusion. Stalin seems to have hoped for active U.S. cooperation in blocking Japan. When this did not happen and the Japanese threat appeared to wane, his interest in close relations slackened. From the U.S. standpoint, the Soviets did not live up to their commitments to stop propagandizing in the United States. Negotiations on loans quickly stalled, and Litvinov took vigorous exception to U.S. demands for payments of old debts. "No nation today pays its debts," an incredulous foreign minister insisted with more truth than diplomacy.30 The anti-Semitic Bullitt found dealing with the Jewish Litvinov especially vexing, and life in the Soviet police state took its toll on American diplomats. Baseball and polo never caught on; there was no Monticello on the Moscow. Relations quickly soured. In 1936, a disenchanted Bullitt departed the Soviet Union a confirmed and virulent anti-Communist.31

The one sentence of FDR's inaugural address devoted to foreign policy included that memorable if also notably vague line "In the field of world policy I would dedicate this nation to the policy of the good neighbor." Meant to apply generally, it became identified with the Western Hemisphere and was one of Roosevelt's most important legacies. A product of self-interest and expediency along with a strong dose of idealism and more than a smattering of genuine goodwill, the Good Neighbor policy in its initial stage terminated existing military occupations and disavowed the U.S. right of military intervention without relinquishing its preeminent position in the hemisphere and dominant role in Central America and the Caribbean. In time, it extended beyond policy into the realm of cultural interchange.32

Hoover laid the foundations. Shortly after the 1928 election, the president-elect carried on the tradition of personal diplomacy begun by Charles Evans Hughes by taking a two-month goodwill tour of Latin America, where he publicly used the phrase "good neighbor." In office, he removed the marines from Nicaragua and promised to get them out of Haiti. He stopped short of publicly repudiating the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, but he explicitly disavowed intervention to protect U.S. investments. He adopted a new and more flexible policy toward recognition. He came very close to apologizing for the U.S. occupation of Haiti and Nicaragua. Building on Wilson's ideas, he sought through commercial and financial arrangements to promote stability in Latin America and thereby create in the Western Hemisphere a model for world peace. His unwillingness to adjust tariff and loan policies to the harsh realities of hard times doomed his economic program. His broader ambitions were subsumed when he became totally absorbed in and ultimately rendered impotent by the Great Depression.33

With his usually keen eye for public relations, Roosevelt made the good neighbor phrase part of his political vocabulary and expanded the policy and the spirit, winning praise at home and respect throughout the hemisphere. In the absence of any immediate threat to the Americas and with trade expansion a high priority, it was expedient to conciliate peoples the United States had often demeaned. The rise of dictators in Central America produced stability and eliminated pressures for U.S. intervention. Roosevelt understood that because of its wealth and power the United States would be an object of resentment among many Latins, but he felt it "very important to remove any legitimate grounds of their criticism."34 The sources of Good Neighborism went much deeper. As it turned away from Europe and Asia in the 1930s, the United States devoted greater attention to its own hemisphere. More important, the depression helped peoples of very different continents identify with each other in ways they had not before. Latin Americans could view their northern neighbors as victims of the same poverty and want they had long endured. As they lost faith in their own exceptionalism, North Americans were less inclined to impose their will and values on others. The easing in the United States during the 1930s of deep-seated racial and anti-Catholic prejudices also made possible greater acceptance of Latin Americans. There was much cross-fertilization of ideas among intellectuals on both continents. In the United States, Latin American and especially Mexican art came into vogue. Latin subjects and stars gained popularity in movie theaters.35

Scarcely had Roosevelt taken office before yet another revolution in Cuba put his good intentions to the test. The depression hit Cuba very hard, sparking an uprising by students, soldiers, and workers against President Gerardo "Butcher" Machado. When Machado responded with state-sponsored terror, FDR sent his friend Welles to Cuba as ambassador to handle the crisis. Welles helped unseat Machado, but two changes of government later the ambassador grew alarmed at the radical turn taken by the revolution. President Ramón Grau San Martin, a stubbornly independent physician and university professor, sought to institute sweeping reforms while workers went on strike and seized the sugar mills. The aristocratic Welles was appalled by the ascendancy of the rabble and worried about Communist influence among the workers. He viewed Grau as well-meaning but fuzzy-minded and hopelessly ineffectual. Although he sought to disguise it as a "temporary" and "strictly limited" intervention, he acted very much in the mode of his predecessors, on several occasions in the fall of 1933 appealing for U.S. troops to restore order and replace Grau with a more dependable government.36

In contrast to his predecessors, FDR refused, an important first step in the Good Neighbor process. Welles withheld recognition from Grau, a powerful weapon by itself. FDR authorized him to use political means to undermine the government and dispatched warships to display U.S. power. But he adamantly rejected repeated appeals for troops. He was influenced by his former Navy Department boss, Josephus Daniels, then ambassador to Mexico, who pooh-poohed Welles's fears of Communism and firmly advised against military intervention. More important, the United States was soon to meet with other hemispheric nations at Montevideo, where intervention was expected to be a key issue, and Roosevelt did not want to carry there the stigma of yet another Cuban intrusion. The urgent need for expanding trade with Latin America put a premium on the velvet glove approach. Ultimately, Welles achieved his goals without use of military force. With his encouragement, a group of army plotters headed by Fulgencio Batista overthrew the Grau government. In time, Batista established a dictatorship that, like Trujillo's in the Dominican Republic, produced order without U.S. occupation or military intervention.37

The issue of military intervention was at the top of the agenda of the Montevideo Conference in September 1933. That gathering was a landmark in that Kentuckian and University of Chicago professor Sophonisba Breckinridge became the first woman to represent the United States at an international conference. Following Hughes's precedent, Hull attended and used his down-home Tennessee political manner to cultivate the Latin delegates, popping in on gatherings to extend a warm handshake and "Howdy do" to sometimes startled diplomats, unpretentiously introducing himself as "Hull of the United States." When the Latin American nations sought from U.S. delegates a firm and unequivocal agreement that "no state has the right to intervene in the internal and external affairs of another," Hull strode boldly to the podium and proclaimed that "no government need fear any intervention on the part of the United States under the Roosevelt administration," winning warm applause from the assembled conferees.38 The agreement that was subsequently signed modified the commitment to exclude treaty obligations. To appease still-uneasy neighbors, FDR shortly after the conference firmly declared that "the definite policy of the United States from now on is one opposed to armed intervention."39

The administration followed with tangible steps. A 1934 agreement with Cuba abrogated the obnoxious Platt Amendment, ending the first phase of the special U.S. relationship with that nation. That same year, the last marines departed Haiti. Two years later, a new agreement was negotiated assigning to Panama a larger share of canal revenues and eliminating the clause in the 1903 treaty giving the United States the right to intervene in its internal affairs.

As part of its shift to non-intervention, the United States in the 1930s also changed its policy on recognition. Washington had frequently withheld recognition to deter revolutions or eliminate governments that had taken power by military means, most recently, of course, in Cuba. A coup by Guardia Nacional commander Anastasio Somoza in Nicaragua in 1936 provided the test case for change. Some Latin American observers even at this point foresaw the sort of brutal dictatorship Somoza would impose. A U.S. diplomat lamented that creation of the Guardia Nacional had provided Nicaragua "with an instrument to blast constitutional procedure off the map," offering "one of the sorriest examples . . . of our inability to understand that we should not meddle in other people's affairs."40 On the other hand, the United States had no enthusiasm for further interference in Nicaragua. Many Latin Americans watched closely to see what U.S. pledges of non-intervention really meant when put to the test. Like Stimson earlier, some U.S. officials concluded that at least a Somoza dictatorship could bring stability to a chronically troubled land. As with many other instances in the world of diplomacy, neither intervention nor non-intervention seemed entirely satisfactory. In this case, the United States chose to err on the side of inaction.

Hull also took the lead in implementing the economic arm of the Good Neighbor policy. A passionate advocate of free trade throughout his career, with Roosevelt's blessings he helped push through Congress in 1934 a Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act that gave the executive broad authority to negotiate with other nations a lowering of tariffs by up to 50 percent. Hull's pet project helped to eliminate the customarily fierce congressional battles over tariffs and the log-rolling that went with them. It has remained the basis for U.S. tariff policy since 1934.41 Under his careful management, the agreements had special application for Latin America. In the case of Cuba and the Central American nations, they encouraged the export of U.S. finished goods and the import of agricultural products like coffee, sugar, and tobacco, thus solidifying a quasi-colonial relationship that stunted their economic development and increased their dependence on the United States. Along with the Export-Import Bank, which provided loans to other nations to purchase goods in the United States, the reciprocal trade agreements helped triple U.S. trade with Latin America between 1931 and 1941. They strengthened the dominant role of the United States in hemispheric commerce.

The Good Neighbor policy was far more than policies and programs; it was also deeply personal and closely identified with Franklin Roosevelt. His genuine affection for people carried over into his foreign policy, as did his ability to identify with what he would call the "common man," something that especially resonated in Latin America. Once as overbearing as cousin Theodore, FDR retained a certain condescension, but he had long since concluded that it was diplomatically expedient—and good politics—to cultivate friendship among the good neighbors. He went out of his way to demonstrate that Latin America counted through such occasions as Pan-American Day in U.S. schools. His commanding presence combined with his populist instincts appealed to Latin Americans, making him the most popular U.S. president ever within the hemisphere at large.42 In 1934, he continued the new tradition of personal diplomacy by visiting South America, even showing up in Haiti, Panama, and Colombia. His arrival at an inter-American conference in Buenos Aires shortly after his overwhelming reelection in 1936 was nothing short of triumphal, a national holiday that drew huge enthusiastic crowds. The Latin American press hailed him as "el gran democrata" whose New Deal served as a model of the kind of reform Latin America needed.43 Buenos Aires represented the capstone of the first phase of the Good Neighbor policy. In a markedly changed climate, FDR had introduced significant changes, most notably a formal end to military interventions and deliberate efforts to cultivate good will, without changing the essence of a patron-client relationship. As the world's attention shifted after 1936 toward the impending crises in East Asia and Western Europe, the Good Neighbor policy would increasingly focus on hemispheric defense.44

As the threat of war mounted in the 1930s, Americans responded with a fierce determination to stay out. A minority of internationalists still favored collective security to prevent war, but most Americans preferred to concentrate on domestic issues, shun international cooperation, retain complete freedom of action, and avoid war at virtually any cost. The term isolationism has often—and mistakenly—been applied to all of U.S. history. It works best for the 1930s.45 To be sure, the United States never sought to cut itself off completely as China and Japan had done before the nineteenth century. Americans took a keen interest in events abroad, maintained diplomatic contact with other nations, and sought to sustain a flourishing trade. But their passionate 1930s quest to insulate the nation from foreign entanglements and war fully merits the label isolationist.

Isolationists did not share the same ideology or belong to any organization.46 They ran the political gamut from left to right. Such sentiment was strongest in the middle western states and among Republicans and Irish and German Americans, but it cut across regional, party, and ethnic lines. Isolationists did share certain basic assumptions. They did not make moral distinctions among other nations. European conflict in particular they viewed as simply another stage in a never-ending struggle for power and empire. When the United States was grappling with limited success to resolve the economic crisis at home, they had no illusions about their ability to solve others' problems. Like Americans since the middle of the nineteenth century, they believed that the crises building in Europe and East Asia did not threaten their security. Although they disagreed, often sharply, on domestic issues and in their willingness to sacrifice trade and neutral rights to avoid conflict, they shared a faith in unilateralism and a determination to stay out of war.

Such views sprang from varied sources. The United States since 1776 had made it a cardinal principle to avoid "entangling" alliances and Europe's wars. In this sense, Americans were simply adhering to tradition. But the Great Depression gave 1930s isolationism a special fervency. With breadlines lengthening and the economy at a standstill, most Americans agreed they should concentrate on combating the depression. Foreign policy fell to the bottom of the national scale of priorities. The depression also shattered the nation's self-confidence, standing on its head the Wilsonian notion that the United States had the answer to world problems. Bitter conflicts over tariffs and Allied default on war debts exacerbated already strained relations with Britain and France, nations with whom cooperation would have been necessary to uphold the postwar order. Hostility toward the outside world increasingly marked the popular mood. "We do not like foreigners any more," Representative Maury Maverick of Texas snorted in 1935.47

Unpleasant memories of the Great War reinforced the effects of the depression. By the mid-1930s, Americans generally agreed that intervention had been a mistake. The United States had no real stake in the outcome of the war, it was argued; its vital interests were not threatened. Some "revisionist" historians charged that an innocent nation had been tricked into war by wily British propagandists. Others blamed Wilson and his pro-British advisers for not adhering to strict neutrality. More conspiratorially, still others argued that bankers and munitions makers—the "merchants of death" theory popularized by a Senate investigating committee headed by North Dakota's Gerald Nye—had pressed Wilson into abandoning neutrality by permitting a massive trade in war materials. When these investments were threatened by a German victory in 1917, it was alleged, these same selfish interests drove him to intervene. Americans generally agreed that their participation had neither ended the threat of war nor made the world safe for democracy.48 Revisionist history provided compelling arguments to avoid repeating the same mistake and historical "lessons" to show how.

Above all, the threat of another war pushed Americans toward isolationism. From 1933 to 1937, Japan consolidated its gains in Manchuria and began to exert nonmilitary pressure on North China. In the spring of 1934, a Foreign Office official publicly proclaimed that Japan alone would maintain peace and order in East Asia. This so-called Amau Doctrine directly challenged Western interests in East Asia and raised the possibility of conflict. In Europe, Benito Mussolini sought to recapture Italy's lost glory by conquering Ethiopia. In a January 1935 plebiscite, the people of the Saar Basin dividing Germany and France voted to join the former. Several months later, Hitler announced that Germany would no longer adhere to the disarmament limits imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. As the threat of war increased in East Asia and Europe, the nation responded with near unanimity. "Ninety-nine Americans out of a hundred," the Christian Century proclaimed in January 1935, "would today regard as an imbecile anyone who might suggest that, in the event of another European war, the United States should again participate in it."49 Scientific surveys of public opinion were just coming into use, and a February 1937 poll indicated that a stunning 95 percent of Americans agreed that the nation should not participate in any future war.

Peace activism flourished. In its heyday, the organized peace movement had an estimated twelve million adherents and an income of more than $1 million. Protestant ministers, veterans, and women's groups led the opposition to war. Pacifists and anti-war internationalists joined forces in 1935 to form an Emergency Peace Campaign that held conferences and conducted study groups across the nation. Its No Foreign War Crusade opened on April 6, 1937, the twentieth anniversary of U.S. entry into World War I, with rallies in two thousand cities and on five hundred campuses. College students formed the vanguard of the antiwar opposition. In April 1935, 150,000 students on 130 campuses participated in anti-war protests; the following year the number increased to an estimated 500,000. Students lobbied to get the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) off campuses. They formed organizations such as Veterans of Future Wars, which, with tongue only partially in cheek, demanded an "adjusted service compensation" of $1,000 for men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-six so they could enjoy "the full benefit of their country's gratitude" before being killed in battle.50

This mood was quickly manifested in policy. In April 1934, Congress passed an act introduced by and named for arch-nationalist and hard-core isolationist Senator Hiram Johnson of California forbidding private loans to nations in default on war debt payments. The Johnson Act was popular at home but mischievous in its consequences. By declaring token payments illegal, it gave debtor nations a handy excuse not to pay. By restricting U.S. freedom of action, it would later impede an effective response to the emerging world crisis.51 Spurred by the right-wing radio priest Father Charles Coughlin and Hearst newspapers, the Senate in January 1935 stunned an unwary and even complacent FDR by once again rejecting U.S. membership in the World Court, a result primarily of continuing hostility to the League of Nations and rising anti-foreignism. "To hell with Europe and the rest of those nations!" a Minnesota senator screamed.52 The defeat left Roosevelt battle-scarred and notably cautious for the struggle ahead.

When German rearmament and Italy's October 1935 attack on Ethiopia transformed issues of war and peace from the abstract to the immediate, the United States sought legislative safeguards for its neutrality. Isolationists were prepared to sacrifice traditional neutral rights and freedom of the seas to keep the United States out of war. An internationalist minority believed that the best way to avoid war was to prevent it and saw neutrality as a means to that end. Working with the League and the Western democracies, they reasoned, the United States could employ its neutrality as a form of collective security to punish aggressors and assist their victims and thus either deter or contain war. Even Roosevelt believed that the United States needed legal safeguards to avoid being dragged willy-nilly into war as in 1917. In early 1935—unwisely as it turned out—he encouraged isolationist senators to introduce legislation.53

FDR's move backfired. He had hoped for a flexible measure that would permit him to discriminate between aggressor and victim, but the Senate legislation imposed a mandatory embargo on shipments of arms and loans to belligerents once a state of war was declared to exist. "You can't turn the American eagle into a turtle," the Foreign Policy Association howled, and Roosevelt sought to alter the legislation to suit his needs.54 But the Italo-Ethiopian conflict heightened fears of war, and Senate leaders warned that if the president tried to buck the tide he would be "licked sure as hell."55 FDR did secure a six-month limit on the legislation, and he may have hoped to modify it later. Preoccupied with the flurry of crucial domestic bills such as Social Security that constituted the so-called Second New Deal and in need of isolationist votes for key measures, he signed in August 1935 a restrictive neutrality law based squarely on perceived lessons from World War I. Once a state of war was determined to exist, a mandatory embargo would be imposed on arms sales to belligerents. Belligerent submarines were denied access to U.S. ports. Remembering the Lusitania, the first step on the road to World War I, Congress also instructed the president to warn Americans that they traveled on belligerent ships at their own risk. The following year radical isolationists tried to extend the embargo to all trade with belligerents, while FDR sought discretionary power to limit trade in critical raw materials and manufactured goods to prewar quotas, a device that in war would favor Britain and France at the expense of Germany. Again unwilling to risk his domestic programs and sensitive to the upcoming presidential election, Roosevelt in March 1936 grudgingly accepted a compromise extending the original act and adding an embargo on loans.56

Historical lessons are at best an imperfect guide to present actions, and, as with the War of 1812 and the Great War, it was much easier for the United States to proclaim a neutrality policy than to implement it. Americans continued to disagree, often heatedly, about the intent of their neutrality. Should it be strictly applied and designed mainly to keep the nation out of war? Or should it allow the president to support collective security by punishing aggressors and assisting victims? Such debates even tore apart pacificist internationalist groups like the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom.57 Not surprisingly, some Americans took sides in the wars that erupted in the mid-1930s and pressed the government to implement a neutrality favorable to their cause. As in earlier wars, even constitutional safeguards could not shield the United States from influencing world events. Whatever it did or did not do, its actions could have significant results, sometimes in ways that Americans did not like. Amidst all the complexity and confusion, FDR struggled to curb aggression without risking war and provoking an isolationist backlash, using the restrictive Neutrality Acts ingeniously and sometimes deviously and seeking ways outside of neutrality to influence world events.

The Italo-Ethiopian War illustrates the problems. That war evoked an especially strong response among African Americans.58 Ethiopia had a special symbolic importance for them because of its place in biblical lore and because it was one of the few areas of Africa not colonized by whites. Involving themselves for the first time in a high-profile foreign policy debate, they vigorously protested Italian aggression and demanded embargoes on trade with Italy, boycotted Italian American businesses in the United States, petitioned the U.S. Catholic hierarchy and the pope, organized mass rallies in major cities, raised funds for Ethiopia, and even in small numbers volunteered to fight in the war until warned that such service violated neutrality laws.59 On the other side, Italian Americans generally backed Italy and protested when the government interpreted the Neutrality Act to favor Ethiopia.

Roosevelt struggled with limited success to implement U.S. neutrality in ways that would stop Italy and deter other aggressors. He invoked the Neutrality Act in recognition that it might hurt Italy more than Ethiopia and in hopes that an arms embargo would support League sanctions against Italy. The government also warned Americans against traveling on belligerent passenger ships, in an effort to hurt the Italian tourism industry. The administration subsequently imposed a "moral embargo," urging businesses to limit trade with Italy to prewar levels. When that failed, it threatened to publish the names of firms trading with Italy.60

Although a clever use of the Neutrality Act, these moves neither bucked up the League nor thwarted Italy. The League did declare Italy the aggressor and imposed limited sanctions. Largely because of British and French fear of war, however, vital items like oil were omitted from the restricted list. This huge loophole significantly mitigated the effects of the already ineffectual moral embargo. The sanctions annoyed Italy without stopping it. Collective security was further undermined when it was revealed that British foreign minister Sir Samuel Hoare and French prime minister Pierre Laval had worked out a plan that would have bought peace by giving two-thirds of Ethiopia to Italy. Undeterred by the weak Western response and using all the instruments of modern war including poison gas, Italy completed its conquest in eight months and then left the League of Nations. The absence of the United States from the League gave the Europeans a handy excuse for inaction; their weakness, in turn, confirmed American distrust and fed isolationist sentiments.61

The Spanish Civil War was equally complex, and the policies developed, for many Americans, were just as unsatisfactory. Right-wing rebels led by fascist Francisco Franco and assisted by Germany and Italy set out to topple militarily a democratic government supported by socialists, Communists, and anarchists, and backed by the Soviet Union, in an especially nasty civil conflict that captured the world's attention. The Spanish Civil War became for many Americans a cause célèbre, an epic struggle between good and evil. Most citizens, to be sure, remained uninformed and indifferent, but groups on each side of the political spectrum took up the cause with near fanatical zeal. Alarmed by the government's treatment of the Spanish church, American Catholics, an increasingly potent political lobby, rallied to Franco. Liberals and radicals, including writers, movie stars, journalists, intellectuals, and left-wing agitators, passionately supported the Loyalists. Some 450 Americans even formed an Abraham Lincoln Brigade to fight for the government. Thrown into battle in early 1937 without adequate preparation, they suffered horrific casualties in what many viewed a noble cause.62

The administration again cooperated with the Western democracies, at least indirectly, but its policies were unpopular at home and had harmful results abroad. Seeking to contain the Spanish Civil War, the British and French naively adopted a policy of non-intervention. The United States went along, refusing to invoke the Neutrality Acts, which, it claimed, did not apply to civil wars, and again proclaiming a moral embargo on the sale of war supplies to both factions. When exporters ignored it, Congress legislated an arms embargo against both sides. With Germany and Italy generously backing the rebels, the moral embargo worked against the Loyalists, which, as a recognized government, could normally expect to procure war supplies from abroad. This so-called malevolent neutrality was designed to keep the United States out of the war and appease American Catholics. It also reflected concern in government circles, especially in the top echelons of the State Department, that a Loyalist victory would lead to a Communist takeover of Spain that might have spillover effects elsewhere in Europe and threaten U.S. trade and investments. Some conservative diplomats termed the war a conflict of "Rebel versus Rabble," "between nationalism on the one hand, and Bolshevism naked and unadorned on the other."63 On the other hand, liberals, even isolationists like Senator Nye, increasingly feared that the United States was abetting a fascist victory. The brutal bombing and shelling of civilians by German and Italian air squadrons at Guernica in April 1937, later immortalized in Pablo Picasso's stunning mural, caused international outrage, an act of "fiendish ferocity" according to one U.S. newspaper.64 The administration nonetheless clung to its policy until Franco triumphed in the spring of 1939, in large part because Roosevelt was immobilized over opposition to his attempt to pack the Supreme Court with sympathetic justices and refused to risk another defeat. Franco later praised the United States for a "gesture we Nationalists will never forget"; FDR conceded a "great mistake."65

The difficulties of implementing neutrality produced in 1937 demands for revision of the legislation. Internationalists still opposed the mandatory arms and loans embargo and sought presidential discretion to support collective security. Increasingly concerned with the threat of war, some members of Congress wanted to close a large loophole by extending the embargo to all goods. Even isolationists like Borah protested the surrender of traditional neutral rights as "cowardly" and "sordid." Still others worried that a total embargo would damage the U.S. economy.

Financier and sometime presidential adviser Bernard Baruch, czar of industrial mobilization during World War I, came up with a clever solution. Insisting that the entanglements of loans and the risk of shipping war materials posed the greatest threats to neutrality, he proposed that the United States "sell to any belligerent anything except lethal weapons, but the terms are 'cash on the barrel-head and come and get it.'" Baruch's scheme offered the allure of peace without sacrificing prosperity. FDR favored cash and carry, recognizing that it could help Britain and France in the event of war. He sought discretionary authority to apply the principle. This time, remarkably, he succeeded. On May 1, 1937, while fishing in the Gulf of Mexico, he signed a measure that retained the embargo on arms and loans and prohibited Americans from traveling on belligerent ships. It also gave the president broad discretionary authority to apply cash-and-carry to trade with belligerents. This compromise permitted Americans to have their cake and eat it too, presumably minimizing the risk of war without abandoning U.S. trade altogether. The New York Herald-Tribune dismissed the 1937 legislation as "an act to preserve the United States from intervention in the War of 1914–'18."66 In fact, by continuing to tie American hands in crucial areas it probably encouraged further aggression and ultimately helped bring on a war the nation could not avoid.

FDR also worked outside the Neutrality Acts in sometimes inscrutable ways in a futile effort to shape world events. He shared the determination of most Americans to stay out of war. The best way to do that, he believed, was to prevent war. He seems early to have concluded that Germany, Italy, and Japan threatened the peace. Recognizing the limits on his own freedom of action, he sought means to "put some steel in the British spine," even regaling British representatives with tales of his time spent in a German school when he had stood up to the local bully. Seeking to "get closer . . . with a view to preventing a war or shortening it if it should come," from 1934 to 1937 he floated various schemes to encourage British resistance to the Axis and build a basis for Anglo-American partnership. He proposed exchanges of information on weapons and industrial mobilization. He approved the Royal Navy keeping in service overage destroyers beyond treaty limits and suggested exchanging sailors on navy ships. As early as 1934, he proposed "united action" to prevent or localize war. He later suggested expanding the doctrine of effective blockade to include land traffic, a means to isolate aggressors that would evolve into his quarantine speech. His major proposal was for an international peace conference to be held under U.S. auspices that would encourage participants to agree upon a set of principles. Should they refuse or agree and later break their promises, they could be branded as outlaws. FDR hoped in the process to educate Americans for the international role they must play.67

Such efforts produced no tangible results. The gap of distrust was too deep to be bridged by small gestures. Whatever FDR might say privately, the British viewed the Neutrality Acts as an insuperable impediment to cooperation with the United States and a sharp limit on the president's ability to keep commitments. They dismissed some of his proposals as "dangerously jejune" and "a little too naive and simplistic." His unorthodox style also caused problems. His proposals were often transmitted in oblique and elliptical fashion and shrouded in secrecy. On occasion, the British missed the signals. In any event, they feared the United States would "let us down or stab us in the back after having thrust us forward to our cost." The ascension of Neville Chamberlain to the prime minister-ship precisely when Roosevelt proposed an international conference was especially bad timing. Chamberlain trusted neither the United States nor Roosevelt. In any event, he was disposed to avoid war through negotiation. FDR's embarrassing defeat in the Court fight made the British even more wary of his ability to follow through on any commitments.68

Just two months after Roosevelt's signing of the 1937 Neutrality Act, war erupted in East Asia. An incident at the Marco Polo Bridge in Beijing on July 7, 1937, sparked fighting between Chinese and Japanese troops that quickly escalated into full-scale war. Unlike Mukden in 1931, the Japanese did not stage this incident. This time it was the civilian government in Tokyo that used the clash to eliminate the Kuomintang threat to Japan's hegemony over an area deemed vital to its security and prosperity. The conflict soon fanned out over North China and spread south. Using modern weapons with ruthless precision, Japanese forces seized Shanghai, China's largest city. They followed with the notorious "rape of Nanking," six weeks of terror marked by rampant burning and looting, the mass execution of prisoners of war, and the merciless slaughter of civilians, women and children included. Countless women were brutally raped and forced into prostitution. In all, as many as three hundred thousand Chinese may have been killed.69 Even these horrific methods could not bring China to heel. Chiang Kai-shek moved his government to Chungking in the hinterland. Bogged down in a more difficult struggle than anticipated, the Japanese fought on to terminate what they euphemistically called the "China Incident."

Reactions in the United States to the Sino-Japanese War varied. Many Americans still saw Japan as a bulwark against Soviet Russia and even against Chinese revolutionary nationalism. Some Americans valued a flourishing trade with Japan. On the other hand, many increasingly took sides. Missionaries who remained to help the Chinese reported the horrors of Japanese aggression; accounts of the rape of Nanking caused particular outrage. Warning that the United States must not be intimidated by "Al Capone nations," missionaries pushed for a "Christian boycott" of Japanese goods and stopping the sale of war materials to Japan. Novelist Pearl Buck and Time-Life mogul Henry Luce, both children of missionary parents, complemented their efforts. Millions of Americans read Pearl Buck's novel The Good Earth, first published in 1931, and identified with the Chinese peasants whose story it told. The movie version appeared in 1937. Luce's increasingly popular high-circulation magazines and March of Time newsreels also presented highly idealized pictures of China and Chiang Kai-shek, a recent convert to Christianity. Over time, such images swayed U.S. opinion against Japan and toward China. Whatever their sympathies, Americans in late 1937 staunchly opposed going to war.70

The official U.S. response to the Sino-Japanese War reflected the nation's ambivalence. As with Ethiopia and Spain, Roosevelt manipulated U.S. neutrality to influence events in ways that he—and most Americans—favored. Recognizing that cash-and-carry would benefit the Japanese and exploiting the absence of a declaration of war, he refused to invoke the Neutrality Acts. But he would go no further, and his subsequent actions were characteristically elusive. In October 1937 in Chicago, a stronghold of isolationism, he briefly heartened internationalists with his famous speech calling for a quarantine of the contagion of aggression, at least hinting at sanctions. Apparently misreading a surprisingly positive national response or uncertain what to do once he received it, he quickly backtracked, affirming the next day that " 'sanctions' is a terrible word to use. They are out of the window." In dealing with the war in Asia, as with other issues, Americans and Europeans brought out the worst in each other. When a League-arranged meeting of the Nine-Power Pact signatories (without Japan) met in Brussels in November 1937, the mere hint of sanctions drew from Hull's State Department a strong disclaimer and call for adjournment. Briefly buoyed by FDR's quarantine speech, the Europeans were no more willing than the United States to risk sanctions. Once again, U.S. unreliability gave them a handy excuse to do nothing. "Hardly a people to go tiger shooting with," Chamberlain's sister sneered.71

Even the Japanese sinking of a U.S. Navy vessel failed to provoke the United States into action. On December 11, 1937, during the height of the rape of Nanking, Japanese aircraft bombed and strafed the USS Panay, a gunboat in the Yangtze River engaged in evacuating civilians. The pilots cruelly attacked survivors seeking to escape in lifeboats. The Panay was sunk; forty-three sailors and five civilians were injured, three Americans killed. FDR and other top officials were furious and contemplated a punitive response. But this shockingly brutal and unprovoked attack sparked little of the rage of the Maine or Lusitania. Indeed, Americans seemed to go out of their way to keep a war spirit from building. Some even demanded that U.S. ships be pulled out of China. Apparently as shocked as the United States, the Japanese government quickly apologized, promised indemnities for the families of the dead and injured, and provided assurances against future attacks. Even more telling, and revealing a different side of Japanese society, thousands of ordinary citizens, in keeping with an ancient custom, sent expressions of regret and small donations of money that were used to care for the graves of American sailors buried in Japan.72

As the Sino-Japanese War settled into a stalemate, the situation in Europe dramatically worsened. Continuing his step-by-step dismantling of the despised Versailles settlement, Hitler in March 1936 sent troops into the demilitarized zones of the Rhineland. He stepped up rearmament, ominously focusing on offensive weapons such as tanks, planes, and U-boats, and also began to form alliances, signing with Italy in October 1936 the Rome-Berlin Axis and with Japan the following month an Anti-Comintern Pact. Fulfilling a long-standing personal dream, the Austrian-born dictator in March 1938 through propaganda and intimidation, and again in violation of the Versailles treaty, forged a union with Austria, sealing the arrangement with a rigged plebiscite in which a resounding 99.75 percent of the voters approved the Anschluss.

Hitler's threats against Czechoslovakia provoked a full-fledged war scare in 1938, what has come to be known as the Munich crisis. Cynically taking up the Wilsonian banner of self-determination, he first demanded autonomy for the 1.5 million German speakers in the Sudeten region of western Czechoslovakia and then cession of the entire Sudetenland to Germany. Fearing that the loss of this mountainous region would deprive it of a natural barrier against a resurgent Germany, the Czech government balked. When troop and ship movements across Europe and even plans for the evacuation of Paris signaled the likelihood of war, Britain and France stepped in to resolve the dispute—at any cost. Accepting at face value Hitler's pledge that "this is the last territorial claim I have to make in Europe," they pushed for a negotiated settlement. When their representatives met with Italy and Germany at Munich in September 1938, they agreed in two short hours to turn over much of the Sudeten territory to Germany in exchange for a four-power guarantee of Czechoslovakia's new borders. The Czechs had little choice but to concede. For much of Europe, the fate of relatively few people and a small slice of territory seemed an acceptable price to avert war. The West relaxed and took comfort from Chamberlain's claims to have achieved "peace in our time." The words would take on a cruelly ironic ring the following year when Nazi troops stormed into Czechoslovakia.73

The United States' role in the crisis was secondary but still significant. Like Europeans, Americans feared the crisis might lead to war—"Munich hangs over our heads, like a thundercloud," journalist Heywood Broun observed.74 They also fervently hoped it could be settled by negotiation, irrespective of the merits of the case. Roosevelt was of mixed mind. Privately he fretted about the sacrifice of principle and the danger of encouraging the appetite of aggressors. Without acknowledging that U.S. inaction had discouraged British and French firmness, he also privately lamented that the Allies had left Czechoslovakia to "paddle its own canoe" and predicted they would "wash the blood from their Judas Iscariot hands."75 At first, he contemplated the possibility of war with equanimity, gratuitously advising a British diplomat in that contingency that the Allies should pursue a defensive strategy and adding customarily vague and qualified assurances of U.S. support. When war seemed imminent, however, he was moved to act. Still painfully aware that public opinion sharply limited his freedom of action, he carefully avoided offers of mediation or arbitration. He actively promoted negotiations without taking a position on the issues. He made clear to Britain and France—and Hitler—that the United States "has no political involvements in Europe, and will assume no obligations in the conduct of the present negotiation." When he learned that negotiations would take place, he tersely and enthusiastically cabled Chamberlain: "Good Man." Like most Americans and Europeans, he was relieved by the Munich settlement and shared Chamberlain's hopes for a "new order based on justice and on law." The United States was not directly complicit in the Munich settlement, but it abetted the policies of Britain and France.76

From the outbreak of war in Europe into the next century, Munich would be the synonym for appeasement, its inviolable lesson the folly of negotiating with aggressors. Like all historical events, its circumstances were unique, its lessons of limited applicability. An angry and frustrated Hitler viewed Munich not as victory but defeat. He had wanted war in 1938 but was maneuvered into negotiations. Unable to wriggle out, he ultimately demurred from war because of the hesitance of his advisers and allies.77 For Britain and France, Munich, however unpalatable, was probably necessary. Both were weak militarily and in no position to fight. British public opinion strongly opposed war, and the dominions were not willing to fight for Czechoslovakia. The Western allies could not depend on the United States or put much faith in Czech resistance. Munich bought them a year to prepare for war. It was also made clear to the Western allies—belatedly to be sure—the full extent of Hitler's ambition and deceitfulness.78

For all parties concerned, Munich was the turning point of the pre–World War II era. Frustrated in 1938, Hitler made sure the next time he got the war he wanted. Certain that the Western powers would not stop Hitler, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin began to contemplate a deal with his archenemy. Having assumed they had bought peace at Munich, the British and French could not but be humiliated by Hitler's subsequent occupation of Czechoslovakia and invasion of Poland and felt compelled to act. In both Britain and France, Munich created a clarity that had not existed before.79

Munich was also a watershed for Roosevelt. Hitler's "truculent and unyielding" response to his appeals for equitable negotiations along with reports from U.S. diplomats in Europe persuaded him that the Nazi dictator could be neither trusted nor appeased.80 He was a "wild man," the president mused, a "nut." Munich also convinced FDR that Hitler was responsible for Europe's drift toward war and might be bent on world domination. The president was no longer casually confident of a British and French victory in the event of war. The Italian prophet of air power, Guilio Douhet, had argued that by terrorizing civilian populations, bombing could win wars. The fear of German air power—put on such brutal display in Spain—paralyzed Europe during the Munich crisis. Roosevelt's exaggerated but very real concerns about German air superiority, in his own words, "completely reinvented our own international relations." For the first time since the days of the Monroe Doctrine, he concluded, the United States was vulnerable to foreign attack. Already alarmed by Germany's penetration of Latin America, he also feared that it might get air bases from which it could threaten the southern United States. "It's a very small world," he cautioned. The best way to prevent Germany and Italy from threatening the United States and keep the United States out of war, he reasoned, was to bolster Britain and France through air power. In the months after Munich, Roosevelt sought a policy of "unneutral rearmament" by securing massive increases in the production of aircraft and repealing the arms embargo to make them available to Britain and France.81

Once again, he failed to get the legislation he wanted. He had suffered a major political defeat in the 1937 Court fight, and his effort to save the New Deal by purging conservative Democrats in the 1938 elections backfired. Those legislators he sought to get rid of survived; the Republicans scored major gains. As a presumed lame duck, he was not in a strong position to move Congress. Now facing even greater opposition, he was loath to risk the prestige of his office on foreign policy legislation he badly needed. Remaining in the background, he entrusted the task to the inebriated, infirm, and inept Senator Key Pittman, who predictably bungled it. Subsequent efforts to secure compromise legislation narrowly failed. In a last-ditch effort to salvage something, Roosevelt and Hull met with legislators at the White House on July 18. The secretary warned that the arms embargo "conferred gratuitous benefit on the probable aggressors." Admonishing that war in Europe was imminent, FDR averred that "I've fired my last shot. I think I ought to have another round in my belt." After a lengthy discussion and informal polling of the group, Vice President John Nance Garner advised the president, "Well, Captain, we may as well face the facts. You haven't got the votes, and that's all there is to it." It would take the harsh reality of war rather than the mere threat of it to push Congress and the nation beyond the position assumed in the mid-1930s.82

Roosevelt was similarly hamstrung in dealing with the tragic plight of German Jews. Upon taking power in 1933, the Nazi regime began systematic persecution, imposing boycotts on businesses, proscribing Jews from certain jobs, and restricting their civil rights. Using as a pretext the shooting of a German diplomat in Paris by a young German-Jewish refugee, it launched after Munich a full-scale campaign of terror. On November 9, 1938, while police did nothing, hooligans pillaged, looted, burned synagogues, and destroyed Jewish homes. A dozen Jews were killed, twenty thousand arrested, and much property destroyed. The shattered glass littering the streets gave the name Kristallnacht (the night of broken glass) to the officially authorized rampage. To compound the injury, the government decreed that the damage be paid for by a tax levied on Jews. Revealing its deeper intentions, it closed Jewish-owned stores and confiscated personal assets. In the wake of Kristallnacht, as many as 140,000 Jews sought to flee Germany.83