"The problems which we face are so vast and so interrelated," Franklin Roosevelt explained to Ambassador Joseph Grew on January 21, 1941, "that any attempt even to state them compels one to think in terms of five continents and seven seas."1 Thus, almost a year before Pearl Harbor, FDR came to appreciate the enormously transformative impact of World War II on U.S. foreign relations. Even prior to December 7, 1941, Americans had begun to reassess long-standing assumptions about the sources of their national security (a phrase just coming into use). While often obscuring the intent and significance of his actions, the president had taken major steps toward intervention in the European and Asian wars. What the fall of France did not accomplish in terms of reshaping American attitudes and institutions, Pearl Harbor did. The Japanese attack on Hawaii undermined as perhaps nothing else could have the cherished notion that America was secure from foreign threat. The ensuing war elevated foreign policy to the highest national priority for the first time since the early republic. By virtue of its size, its wealth, its largely untapped economic and military potential, and its distance from major war zones, the United States, along with Britain and the Soviet Union, assumed leadership of what came to be called the United Nations, a loose assemblage of some forty countries. During the war, it built a mammoth military establishment and funded a huge foreign aid program. It became involved in a host of complex and often intricately interconnected diplomatic, economic, political, and military problems across the world, requiring a sprawling foreign policy bureaucracy staffed by thousands of men and women engaged in all sorts of activities in places Americans could not previously have located on a map. This time, Americans took up the mantle of world leadership spurned in 1919. "We have tossed Washington's Farewell Address in to the discard," Michigan's isolationist senator Arthur Vandenberg lamented before Pearl Harbor. "We have thrown ourselves squarely into the power politics and power wars of Europe, Asia, and Africa. We have taken the first step upon a course from which we can never hereafter retreat."2

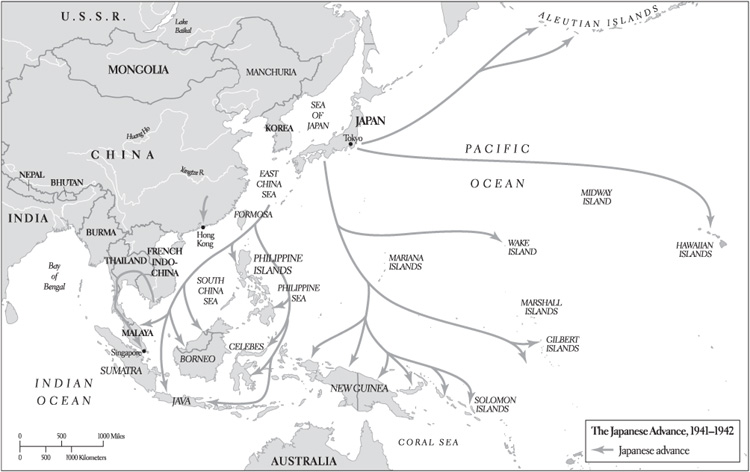

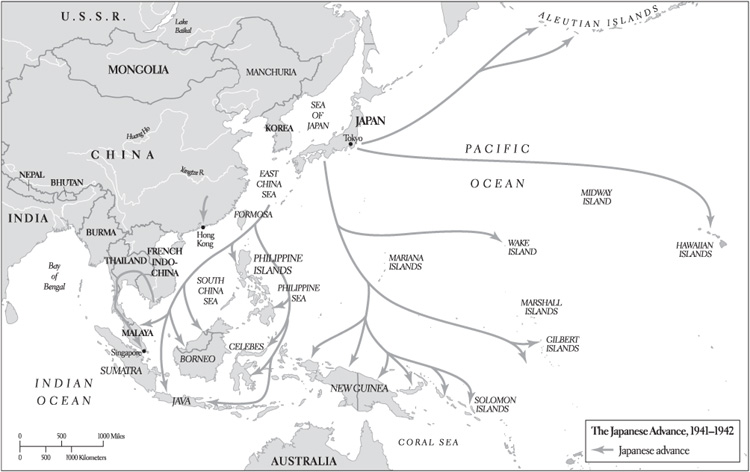

The military situation in the months after Pearl Harbor was unremittingly grim. From January to March 1942, FDR speechwriter Robert Sherwood later recalled, Japan swept across the Pacific and Southeast Asia with such stunning speed that the "pins on the walls of map rooms in Washington and London were usually far out of date."3 Singapore fell on February 15, "the greatest disaster to British arms which our history records," according to Prime Minister Winston Churchill.4 By mid-March, Japanese forces had conquered Malaya, Java, and Borneo, landed on New Guinea, and occupied Rangoon. For weeks, U.S. and Filipino troops valiantly held off enemy invaders. Without food, clothing, and drugs, exhausted from disease and malnutrition, they fell back to Bataan and then Corregidor and finally surrendered on May 6. From Wake Island in the Central Pacific to the Bay of Bengal, Japan reigned supreme.

In Europe, Hitler had delivered on his promise of a "world in flames." Germany retained the upper hand in the Battle of the Atlantic through much of 1942, destroying eight million tons of shipping and threatening to sever the vital trans-Atlantic lifeline. The Axis controlled continental Europe. The Red Army had stopped the Wehrmacht short of Moscow and with the help of "General Winter" had mounted a counteroffensive, but Germany remained strong enough to launch a spring 1942 offensive that once again threatened Soviet defeat. Hitler sent armies into North Africa to seize the Suez Canal and cripple British power in the Middle East. Through Gen. Erwin Rommel's brilliant generalship, the Germans nearly succeeded in the early summer of 1942. Had Spain bowed to Hitler's pressure and entered the war, Germany could have controlled Gibraltar and the Mediterranean. At the height of their power, the Axis dominated one-third of the world's population and mineral resources. The Allies most feared in these perilous months an Axis linkup in the Indian Ocean and central Asia to defeat the USSR, secure the vast oil reserves of the Middle East, and end the war.

Although nowhere near ready for a two-front war, the United States was much better prepared than in 1917. The National Guard was called to active duty, and a selective service system had been in place for more than a year, expanding the army from 174,000 in mid-1939 to nearly 1.5 million two years later. By 1945, the nation had more than 12.1 million men and women in uniform. In the months before Pearl Harbor, the army had trained with antiquated equipment and makeshift substitutes. American industry could not produce the supplies needed to rearm the United States and fill the plates of allies seated at what Churchill called "the hungry table." But Roosevelt had used the emergency of 1940–41 to set ambitious production goals, doubling the size of the combat fleet and producing 7,800 military aircraft. By removing any doubt about full U.S. involvement in the war, Pearl Harbor eliminated the last barrier to full mobilization. War production stimulated a stagnant economy, brought spare production into operation, and converted unemployment into an acute labor shortage. It would be 1943 before the miracle of U.S. war production was fully realized, but it was evident much sooner that Roosevelt's goals, seemingly fantastic at the time, would be far surpassed.

With the onset of global war, the making of foreign policy became more complex—and even more disorderly. The president's advisers were deeply divided both ideologically and on the basis of personality. Vice President Henry A. Wallace became the most vocal spokesman for a liberal internationalism that would extend the benefits of the New Deal to other peoples, provoking conservatives to denounce him and his "radical boys" as the "postwar spreaders of peace, plenty, and pulchritude."5 The State Department receded further into the background, in part from FDR's disdain for that "haven for routineers and paper shufflers."6 In addition, the escalating Hull-Welles feud nearly paralyzed the department until Hull's cronies forced the undersecretary's dismissal after revelations of a homosexual encounter. A crippled and demoralized department continued to shape trade policy and produced reams of paperwork on postwar issues, but the exhausted and increasingly dispirited Hull was not invited to the major Big Three conferences and did not even get minutes of the 1943 Casablanca meeting.

Others filled the vacuum. Elder statesman Henry Stimson presided over war production and played a key role in developing the atomic bomb. Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr. exploited his position as FDR's Hudson Valley neighbor to frame postwar economic programs and encroach on State's turf in designing policies for China and postwar Germany. Dubbed by Churchill "Lord Root of the Matter" for his incisive mind and matter-of-fact approach to problem-solving, the cadaverous former social worker and New Deal relief administrator Harry Hopkins remained the president's alter ego until chronic illness and a mysterious parting of the ways with his boss reduced his influence. The indispensable person was Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall. He "towers above everybody else in the strength of his character and in the wisdom and tactfulness of his handling of himself," Stimson observed with obvious admiration. Marshall brought stability to the chaos that was wartime Washington. An administrative genius, he was, in Churchill's words, the "true 'organizer of victory.' "7

To meet the rapidly expanding demands of a host of new global diplomatic and military problems, FDR created a huge foreign policy bureaucracy that would become a permanent fixture of American life. Even before Pearl Harbor, he concluded that the State Department could not cope with the exigencies of total war. Thus, as with New Deal domestic programs, he established emergency "alphabet soup" agencies. Some of them were given deceptively innocent names, perhaps reflecting the nation's continuing innocence, more likely to obscure their purpose. An Office of Facts and Figures, later the Office of War Information (OWI), was responsible for propaganda at home and abroad; The Coordinator of Information, precursor to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)—and subsequently the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)—was America's first independent intelligence agency.

These new agencies assumed various wartime tasks. OWI censored the press and churned out posters, magazines, comic books, films, and cartoons to undermine enemy morale and sell the war and U.S. war aims to allies and neutrals.8 The Office of Lend-Lease Administration (OLLA) ran that essential wartime foreign aid program.9 Wallace's Board of Economic Warfare (BEW) conducted preemptive purchasing to keep vital raw materials out of enemy hands and manipulated trade to further the war effort. The Office of Foreign Relief and Rehabilitation Operations (OFRRO) handled relief programs in liberated areas. Headed by a World War I Medal of Honor winner, the flamboyant Col. William "Wild Bill" Donovan, the OSS at its peak employed thirteen thousand people, as many as nine thousand overseas. Bearing a distinct Ivy League hue, it brought to Washington scholars such as historians Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and Sherman Kent, and even the Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse, to analyze the vast amounts of information collected on enemy capabilities and operations. Clandestine operatives such as the legendary Virginia Hall slipped into North Africa and Europe to prepare the way for Allied military operations and carried out black propaganda operations and "dirty tricks" in Axis-occupied areas and enemy territory. OSS agents in various guises worked with partisan and guerrilla groups in the Balkans and East Asia. In Bern, a Secret Intelligence unit headed by Allen Dulles established contact with opponents of Hitler and gathered information about the Nazi regime.10

The emergency agencies had a mixed record. BEW had more than two thousand representatives in Brazil, provoking the foreign minister half-jokingly to tell a U.S. diplomat that if more "ambassadors of good will" were sent to his nation "Brazil would be obliged to declare war on the United States."11 In best Rooseveltian fashion, there was rampant overlap of responsibility and duplication of effort. A "coordinator" in wartime Washington, Wallace joked, "was only a man trying to keep all the balls in the air without losing his own."12 Bitter turf battles set off what one official deplored as "another war."13 The squabbles in Washington undoubtedly pleased a president who seemed to enjoy such things, but conflict in North Africa between civilian relief agencies grew so disruptive that the army had to take over. When an especially nasty feud between Wallace and conservative Secretary of Commerce Jesse Jones went public, the president relieved Wallace and combined the economic agencies into the Foreign Economic Administration. Despite their incessant squabbling, the agencies carried out essential wartime tasks. They were also a prolific breeding ground for postwar internationalism, providing a baptism by fire for such prominent postwar leaders as George W. Ball, Adlai E. Stevenson, and Dulles.

World War II also thrust the military into a central role in formulating U.S. foreign policy. Traditionally, the armed forces had carried out policies designed by civilian leaders, but the nation's full-scale engagement in a total and global war and its involvement with a coalition pushed them into the realm of policymaking and diplomacy. Military ascendancy also resulted from Hull's rigid insistence on the artificial distinction between political and military matters and Roosevelt's growing dependence on his uniformed advisers. FDR initiated the process in 1939 by bringing them into the Executive Office of the President, thus bypassing the war and navy secretaries. In February 1942, he created the Joint Chiefs of Staff, composed of the service chiefs. In July, he named former chief of naval operations Adm. William Leahy his personal chief of staff with the primary duty of maintaining liaison between the White House and the Joint Chiefs. In this new role, the top brass formulated strategic plans. They accompanied the president to all his summit meetings, where they coordinated with Allied counterparts plans and operations. The emergence of the military into a key policymaking position brought enduring changes in civil-military relations and the formulation of national security policy.14

The military's new headquarters in Arlington, Virginia, symbolized its growing importance in the Washington power equation. Begun on September 11, 1941, and occupied in 1942, this five-sided monstrosity with its miles of baffling corridors—"vast, sprawling, almost intentionally ugly"—housed some thirty thousand employees in 7.5 million square feet of floor space. Roosevelt disliked the building's architecture and assumed at war's end it would be used for storage. In fact, it remained in full operation. The very word Pentagon in time came to represent throughout the world the enormous military power of the United States—and, in the eyes of domestic and foreign critics, the allegedly dominant and sinister influence of the military in American life.15

Responsibility ultimately rested in the firm hands of the commander in chief. By this time sixty years old, FDR was weary from the strains of eight demanding years in the White House and his long struggle with polio. But the new challenges of global war reinvigorated him. He retained the undaunted optimism that was such an essential part of his personality, as necessary in 1942 as a decade earlier. "I use the wrong end of the telescope," he wrote Justice Felix Frankfurter in March, "and it makes things easier to bear."16 He inspired Americans and others with his lofty rhetoric. He reveled in the ceremonial aspects of his job as commander in chief and delighted in the formulation of grand strategy. Always inclined toward personal diplomacy, he took special pleasure in his direct contact with world leaders such as the sinister and Sphinx-like Joseph Stalin and the bulldog Churchill. His broad circle of personal contacts provided him invaluable information outside regular channels. His chaotic administrative style supposedly left him firmly in control, but as the problems of global warfare became more numerous, more diffuse, and more complex, it also produced serious policy snafus (an acronym that grew out of bureaucratic foul-ups in World War II and stood for "situation normal, all fucked up") and gave clever subordinates the opportunity for freelancing, sometimes with baleful results. Not surprisingly, he continued to rely on obfuscation and outright deceit. "You know I am a juggler," he confessed in the spring of 1942, "and I never let my right hand know what my left hand does. . . . I may have one policy for Europe and one diametrically opposite for North and South America. I may be entirely inconsistent, and furthermore I am perfectly willing to mislead and tell untruths if it will help win the war."17

Some critics claim that Roosevelt's wartime leadership lacked guiding principles, that he drifted from crisis to crisis without a clear sense of purpose or direction. Others insist that in fighting the evils of Nazism he was blind to the dangers of Communism. Still others contend that he and his military advisers focused too much on winning the war and gave insufficient attention to crucial political issues.

In truth, FDR was in many ways a brilliant commander in chief. He effectively juggled the many dimensions of the job. He skillfully managed the war effort and doggedly defended U.S. interests. Keenly aware of the dynamics of coalition warfare, he alone among Allied leaders had what he called a "world point of view."18 He correctly gave highest priority to holding the alliance together and winning the war, essential given the desperate situation of 1942 and the vastly divergent interests and goals of the major Allies. At times he seemed to act on whim or to muddle through, but he had a coherent if not completely formulated or publicly articulated view for the peace. Like Wilson, he firmly believed in the superiority of American values and institutions. He was also certain that postwar peace and stability depended on the extension of those principles across the world and that other peoples would accept them if given a chance. By providing a middle ground between the totalitarianism of left and right, the New Deal, in his view, pointed the way to the future, and he saw in the war an opportunity to promote world reform along those lines. At the same time, as Robert Sherwood observed, "the tragedy of Wilson was always somewhere within the rim of his consciousness."19 He saw better than his mentor the limits of American power; he intuitively understood that diplomatic problems were not always susceptible to neat solutions. Roosevelt's pragmatic idealism, Warren Kimball has observed, thus "sought to accommodate the broad ideas of Woodrow Wilson to the practical realities of international relations."20 Global war provided the ultimate test for his enormous political skills; the untimeliness of his death ensured for him an uncertain legacy.

"There is only one thing worse than fighting with allies," Churchill asserted on the eve of victory in World War II, "and that is fighting without them!"21 Although an exercise in Churchillian hyperbole, the observation underscores a fundamental reality of coalition warfare: Alliances are marriages of convenience formed to meet immediate, often urgent needs. They contain built-in conflicts; their usefulness rarely extends beyond achievement of the purposes for which they were formed. Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States were forced into partnership in the summer of 1941 by the mortal threat of Nazi Germany. They agreed that Hitler must be defeated. They collaborated effectively to that end. But they brought to the alliance deep-seated mutual suspicions. They disagreed sharply on how and for what goals the war should be fought.

Throughout their wartime partnership, the major Allies viewed each other with profound distrust. The Soviet leaders had gained power by conspiratorial means and were suspicious by nature. Indeed, there is ample evidence that at various points Stalin suffered from acute paranoia. Communist ideology taught hatred of capitalism and seemed validated by history: the Allied interventions of 1918–19 designed in the Soviet view to overthrow their fledgling government; the long period of diplomatic ostracism by the West; and the Munich agreement that left the Soviet Union exposed to Nazi power. They had no choice but to turn to the Western nations in June 1941 but remained wary of their allies. While traveling in the West, Foreign Minister V. M. Molotov slept with a revolver under his pillow. "Churchill is the kind who, if you don't watch him, will slip a kopek out of your pocket . . . ," Stalin told a Yugoslav Communist in 1944. "Roosevelt is not like that. He dips his hand in only for bigger coins."22 Westerners reciprocated Soviet suspicions. Churchill brought to the alliance a well-earned reputation as a Bolshevik-hater, and many Britons shared his view. The deeply emotional antipathy of Americans toward Communism was reinforced in the 1930s by Stalin's bloody purges of top party officials, his sordid 1939 pact with Hitler, and the "rape" of Poland and Finland. They only grudgingly acquiesced in Roosevelt's 1941 efforts to assist the Soviet Union. They warmed to the Russian people and even "Uncle Joe" Stalin somewhat during the war, but old fears never entirely dissipated.23

During World War II, the United States and Britain achieved probably the closest collaboration by any allies in time of war. Top military leaders worked together through a Combined Chiefs of Staff. The nations shared economic resources. They even agreed to share vital information on such top-secret military projects as the atomic bomb (which was not given the Soviet Union), although in this area Britain repeatedly protested that its ally did not keep its promises. Roosevelt and Churchill established a rare camaraderie, communicating almost daily during much of the war. Yet these two extraordinarily close allies remained deeply suspicious of each other. An ancient strain of Anglophobia in American life manifested itself repeatedly during the war. Britons saw better than Americans, and naturally resented, that the seat of world power was passing to the trans-Atlantic upstart. The two nations fought bitterly over strategy and trade issues. Despite their genuine friendship, Roosevelt and Churchill suspected one another and clashed over sensitive questions like the future of the British Empire.24

The three Allies were deeply divided on grand strategy. With much of its territory occupied by the Wehrmacht, the Soviet Union desperately needed material aid and the immediate opening of a second front in Western Europe to ease pressure on the embattled Red Army. Some U.S. Army planners agreed with the Soviet approach, if not with its timing. But U.S. Navy leaders after the humiliation of Pearl Harbor pushed for all-out war against Japan, and they gained support from Gen. Douglas MacArthur and much of the American public. The British posed a major roadblock to Stalin's demands. They vividly recalled the slaughter of 1914–18 and perceived that an early second front would necessarily be made up mainly of British troops. Thus they opposed an invasion of Western Europe until the Allies had gained overwhelming preponderance over Germany. Britain and especially Churchill also promoted operations around the periphery of Hitler's Fortress Europe to protect their imperial interests in the Middle East, southern Europe, and South Asia. For Stalin, such operations, however useful, were not enough. The U.S. brass vigorously objected to what they considered pinprick operations to pull British imperial chestnuts out of the fire.25

The Allies also disagreed sharply over war aims. Even with the Red Army reeling in the summer of 1941, Stalin made clear his determination to retain the Baltic States and those parts of Poland acquired in his deal with Hitler. His larger aims, like the man himself, remain shrouded in mystery, probably shifting with the circumstances of war. Ideology undoubtedly shaped the Soviet worldview, but Stalin's goals seem to have originated more from Russian history.26 He had no master plan for world conquest. Instead, he was a cautious expansionist, improvising and exploiting opportunities. At a minimum, the Kremlin sought to prevent Germany from repeating the devastation it had inflicted on Russia in the First World War and the early stages of the Second. Stalin also wanted a buffer zone in Eastern and Central Europe made up of what he called "friendly" governments, which meant governments he could control.27 The British hoped to restore a balance of power in Europe, the traditional basis of their national security, which required maintaining France and even Germany as major powers. Despite an explosion of nationalism in the colonial areas during the war, Churchill and other Britons clung to the empire. "I have not become the King's First Minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire," the prime minister once snarled.28 The war aims of the United States were less tangible but no less deeply held. Political settlements should be based on the concept of self-determination of peoples; colonies should be readied for independence; an Open Door policy should govern the world economy; and a world organization should maintain the peace.

Unlike Wilson, who had insisted that the United States fight as an "associated" power, Roosevelt assumed leadership of the United Nations—indeed, he coined the term during Churchill's late 1941–early 1942 visit to Washington, delightedly wheeling into the prime minister's quarters and informing him while he bathed.29 The challenges were formidable. The president had to resist domestic political and navy pressures to scrap the Germany-first strategy and avenge Pearl Harbor. He had to deflect demands from his top military advisers to push U.S. rearmament at the expense of the Allies' immediate and urgent material needs. He had to resolve strategic disputes among the Allies and avert or resolve incipient conflicts over war aims. Above all, he had to hold the alliance together and employ its resources in ways best calculated to defeat its enemies.

To avoid divisive and possibly fatal conflict over war aims—and also the unpleasant situations he so disliked—FDR insisted that political issues not be resolved—or even for the most part discussed—until the war had ended. Such a course held great risk. The momentum and direction of the armies would likely determine, possily to U.S. detriment, the shape of territorial settlements. Roosevelt was also criticized after the war for failing to extract major political concessions from both allies while they were most dependent on the United States. Such arguments do not hold up under close scrutiny. Stalin might well have acceded to U.S. demands in 1941 only to break agreements later if it suited him. In any event, in the dark days of 1941–42, to have extorted concessions at the point of a gun might have critically set back or destroyed the Allied war effort.

Roosevelt used lend-lease to hold the alliance together and also as an integral part of what historian David Kennedy has called his "arsenal of democracy strategy."30 After Pearl Harbor, his military advisers insisted on top priority for precious supplies, arguing that if the United States was ever to take the offensive, "we will have to stop sitting on our fannies giving out stuff in driblets all over the world."31 Looking at the war from a broader perspective, FDR perceived that lend-lease could assure allies of U.S. good faith and increase the fighting capabilities of armies already in the field, thus keeping maximum pressure on the enemy while his nation mobilized. He was also shrewd enough to recognize that supplying Allied armies would produce victory with less cost in U.S. lives. He thus gave Allied claims equal, in some cases higher, priority than U.S. rearmament. He used supplies with an eye to psychological as well as military impact. After Britain's devastating defeat at Tobruk in the summer of 1942, he sent three hundred of the newest Sherman tanks, a huge morale booster. He gave aid to Russia top priority among all competing claims and exerted enormous effort to deliver the goods.32 The administration rejected British proposals to pool resources. Nor did it ever completely do away with the "silly, foolish old dollar sign," and at Congress's insistence it kept detailed records of the cost of every item shipped. Under FDR's leadership, the United States provided more than $50 billion in supplies and services to fifty nations, roughly half of it to the British Empire, around one-fifth to the USSR. Aid to Britain alone included some 1,360 items, everything from aircraft to cigarettes to prefabricated housing for factory workers. Soviet leaders often complained about the paucity and slowness of U.S. lend-lease shipments, but at Yalta in February 1945 the normally laconic Stalin paid eloquent tribute to its "extraordinary contribution" to Allied victory.33

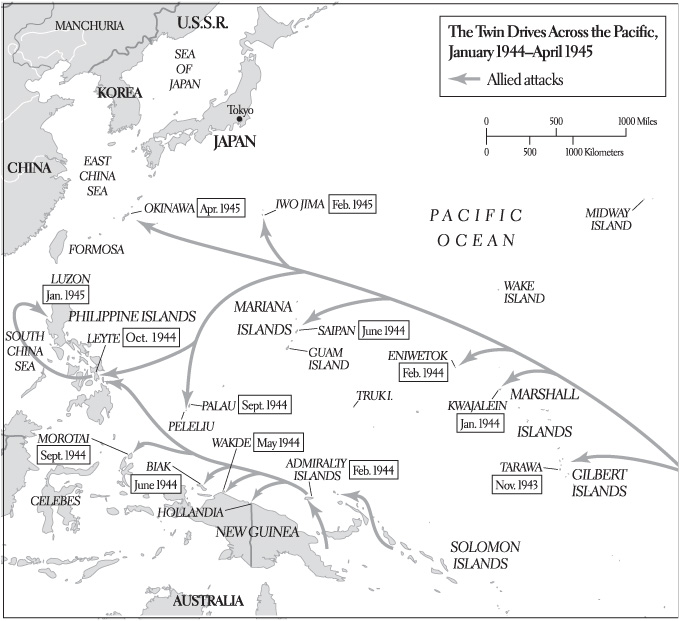

Above all else, the questions regarding the timing, location, and priority to be given military operations divided the Allies. For the United States, the first major issue was the importance to be assigned the Pacific war. After Pearl Harbor, MacArthur and the navy insisted that they must have substantial reinforcements merely to hold the line. Large and vocal segments of public opinion demanded vengeance against Japan. A major U.S. naval victory at the Battle of Midway in June 1942 helped stabilize lines in the Pacific. But Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Ernest King continued to push for limited offensives to exploit Japan's overextension. MacArthur—for once—agreed with the navy. When the depth of British opposition to an immediate second front in Western Europe became clear, even General Marshall supported a shift to the Pacific.34

Roosevelt solved the issue in typical fashion. He diverted substantial supplies to MacArthur and King for limited offensives. As late as 1943, resources and manpower allocated to Europe and the Pacific were roughly equal, violating the spirit and letter of the Europe-first principle. In part, this outcome reflected the influence of King. A bad-tempered, ruthless infighter whose motto was "When the going gets rough they call on the sons of bitches," he secured Marshall's support by backing army proposals for the European theater.35 In diverting resources to the Pacific, Roosevelt may also have been responding to domestic pressures. He certainly hoped to sustain the fighting spirit of forces there and to maintain maximum pressure on all fronts.

At the same time, he stuck with the principle that Germany was the major enemy and had first claim on resources for a major offensive. He rejected proposals to punish the British by shifting to the Pacific—that would be like "taking up your dishes and going away."36 In 1943, when European operations began to take form and the Pacific theater demanded more and more, he put on the brakes, preventing the war against Japan from absorbing resources that would further delay cross-Channel operations. The result was a strategy that retained but modified the Germany-first principle. Europe kept top priority for a major offensive, but the United States committed itself to wage war vigorously on both fronts. This put enormous strain on relations with Britain and the USSR. MacArthur and King predictably complained they could not carry out assigned tasks. In the final analysis, however, it proved a viable strategy for a two-front war, bringing the defeat of Japan months after V-E Day.

Controversy over the time, place, and size of a second front in Europe strained the alliance to the breaking point between January 1942 and the Tehran Conference in late 1943. In part, the conflict derived from Soviet demands for an immediate Anglo-American invasion of Western Europe. But it was also a question of British versus U.S. military doctrines and the Mediterranean against Western Europe. Here too, Roosevelt made the major decisions. Again, they reflected political and psychological considerations and produced compromises, in this case, short-term commitment to the peripheral strategy, long-run commitment to a cross-Channel invasion.

The central question—and the most important and divisive issue among the Allies until late 1943—was whether to mobilize resources for an early strike across the English Channel or mount lesser offensives around the periphery of Hitler's Fortress Europe. Following principles deeply rooted in their respective military traditions, Marshall and the U.S. Army generally favored the former, the British the latter. Roosevelt in May 1942 made an ill-advised, if carefully qualified, commitment to Foreign Minister Molotov for an early second front, which the Russians appear not to have put much stock in. A month later, to the consternation of his own military advisers, he approved British proposals for Operation Torch, an immediate invasion of French North Africa. The decision arose from Britain's steadfast rejection of an immediate invasion of France. Since the British would provide the bulk of the troops for such an operation, FDR felt compelled to attack somewhere else. He was thinking of domestic politics; he desperately wanted to get U.S. troops into action against Germany in 1942. He also acted on the basis of immediate military and psychological concerns. Germany's summer offensive in Russia threatened a breakthrough into the Caucasus and Iran. Rommel's victory at Tobruk gave the Germans the upper hand in North Africa and threatened the union of two victorious German armies in an area of huge strategic importance. A U.S. offensive might tip the scales back toward the Allies.37

Roosevelt was also concerned about the immediate political and psychological needs of an ally. British morale was badly shaken by defeats in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Churchill was in political trouble. A North African offensive might bolster flagging British spirits, end at least temporarily the raging controversy over the second front, and seal the Anglo-American alliance. Roosevelt recognized that it would not appease Stalin, whose complaints had become increasingly shrill. But he apparently reasoned that action somewhere would be better than further delay. He gambled that the Russian armies would survive and sought to compensate by stepping up crucial lend-lease deliveries.38

As U.S. military planners had feared, the invasion of North Africa in November 1942 was followed by agreement at an Anglo-American summit in Casablanca in January 1943 to invade Sicily and then Italy. Since operations in North Africa and the Pacific were absorbing increasing volumes of supplies, the British now argued that the Allies lacked sufficient resources to mount a successful invasion of France and insisted that they follow up victories in the Mediterranean. Divided among themselves, U.S. military planners were no match for their British counterparts. "We came, we listened, and we were conquered," one officer bitterly complained.39 The harsh reality was that as long as the British resisted a cross-Channel attack and the United States lacked the means to do it alone, there was no other way to stay on the offensive. In any event, logistical limitations likely prevented a successful invasion of France prior to 1944. As a way of palliating Stalin's Russia, the "ghost in the attic" at Casablanca, in Kimball's apt words, Roosevelt and Churchill proclaimed that they would accept nothing less than the unconditional surrender of the Axis. The statement also reflected FDR's determination to avoid repeating the mistakes of World War I, as well as his firm belief that Germany had been "Prussianized" and needed a complete political makeover.40

These decisions had vital military and political consequences. The dispersion of resources, as Marshall and others repeatedly warned, delayed a cross-Channel attack until 1944. By giving the Germans time to strengthen their defenses in France, it made the task more costly. Repeated delays in the second front strained the alliance with Moscow in ways that could not be overcome by Roosevelt's soothing words, lend-lease diplomacy, or unconditional surrender. They probably encouraged Stalin to pursue the possibility of a separate peace with Germany in the spring and summer of 1943. It may be argued, on the other hand, that Roosevelt's decisions over the long run better served the Allied cause. Without a full-fledged British commitment, a cross-Channel attack in 1943 might have failed. Even if the British had been compelled to go along, an assault as early as the spring of 1943 ran huge risks. Defeat or stalemate in Western Europe, in the absence of operations elsewhere, could have had profound political and military consequences. The Torch and Casablanca decisions sealed the Anglo-American alliance at a critical point in the war. They permitted maximum use of British manpower and supplies, enabled the Allies to stay on the offensive, and kept pressure on the Germans. In time, they opened the Mediterranean to Allied shipping, knocked Italy out of the war, helped keep Turkey and Spain neutral, and strained German manpower and resources. They provided useful lessons for the cross-Channel attack. The peripheral approach was costly, but given the realities of 1942 and 1943 it seems the strategy most appropriate for coalition warfare.41

What eventually made the Mediterranean strategy work was Roosevelt's unstinting commitment to a knockout blow across the Channel. He never lost sight of its military and political significance. And as the balance of power within the alliance shifted in mid-1943 and the United States, by virtue of its vast manpower and resources, became the dominant partner, grand strategy conformed more with the American—and Russian—than the British design.

When Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin met together for the first time at Tehran in early December 1943, the Allied military situation had improved dramatically. At Stalingrad in late 1942, the Red Army had turned back Hitler's drive into the Caucasus, inflicting huge losses on the Wehrmacht. In July 1943, the Soviets repulsed Germany's summer offensive against the Kursk salient in a titanic battle featuring thousands of tanks. The Reich never regained the initiative in the east. The Red Army by late 1943 had liberated much of Russia proper and was poised to drive across Eastern Europe to Berlin. The Western allies had wrapped up operations in North Africa and implemented successful, if costly, invasions of Sicily and Italy. Allied victory was assured; it was a matter of how long and at what cost.

Amidst much ceremony and pomp at Tehran, the Big Three, as they came to be called, began to discuss postwar issues and set Allied strategy for the rest of the war. The Americans found Stalin—whom one official aptly labeled a "murderous tyrant"—to be intelligent and a master of detail. The tone of the meetings was generally cordial and businesslike. Seeking to promote cooperation, FDR went out of his way to ingratiate himself with the Soviet dictator, meeting privately with him and even teasing a not-at-all amused Churchill in Stalin's presence. The conferees reached no firm political agreements. They spoke of dismembering Germany. Certain that the USSR would be the dominant power in Eastern Europe and that he could not keep U.S. troops in Europe after the war, FDR hinted to Stalin that he would not challenge Soviet domination of the Baltic States and preeminence in Poland, although he urged token concessions to quiet protest in the West. His refusal to make any commitments, on the other hand, and his failure to mention the atomic bomb project, which Stalin knew about, likely gave the suspicious Soviet leader pause.

The main decision was to confirm the cross-Channel attack. Churchill continued to promote operations in the Mediterranean. At one point, FDR appeared to agree with him. To the great relief of top U.S. military leaders, Stalin dismissed further Mediterranean operations as "diversions" and came down firmly behind an invasion of France. The conferees set the date for May 1944. Stalin agreed to time a major offensive with the invasion of France and to enter the war against Japan three months after the defeat of Germany. The discussions at Tehran decisively shaped the outcome of the war and the nature of the peace. Primarily through Roosevelt's leadership, the Allies had emerged from a period of defeat and grave internal tension and formed a successful grand strategy.42

Alliance diplomacy tells only part of the much larger story of U.S. foreign relations in World War II. In a total war fought across a global expanse, the United States mounted an unprecedented range of activities even in places where its prior involvement had been slight. In regions of traditional importance such as Latin America and China, it assumed a much larger role and greater responsibilities. In areas such as the Middle East and South Asia, it took a much keener interest and acquired new commitments. The overriding objective, of course, was defeating the Axis, but Americans in Washington and far from home were also alert to postwar economic and strategic advantage. Certain that greater U.S. involvement was essential for postwar peace and security and to improve the lot of other peoples, they found themselves entangled in intractable issues such as decolonization and the Jewish quest for a homeland in Palestine that would dominate the agenda of world politics for years to come. They plunged into complex local situations not easily susceptible to U.S. power and raised expectations difficult to meet. They early experienced the burdens and frustrations of world power.

Long before Pearl Harbor, the United States had moved to counter the Axis threat to the Western Hemisphere, and during the war the Roosevelt administration intensified its efforts to promote regional security. Building on the foundations of the Good Neighbor policy, U.S. officials continued to speak of a Western Hemisphere ideal and hold up the American "republics" as alternatives to fascism. Roosevelt even boosted the inter-American "system" as a model for postwar order in which great powers would maintain regional harmony and stability through wise leadership and by actively cultivating good relations among their neighbors, using police powers only when essential and then with equity and justice. The Good Neighbor policy was a "radical innovation," journalist Walter Lipp-mann proclaimed, a "true substitute for empire."43

Thanks in part to the attention lavished on the hemisphere during the 1930s, the United States secured the active support of most Latin American nations after 1941. United States officials preferred that the other American "republics" merely break diplomatic relations with the Axis, since full belligerency would have compounded already daunting defense and supply problems. To curry U.S. favor—and secure economic aid—the Caribbean and Central American nations, most of them dictatorships, exceeded U.S. wishes by quickly declaring war. Mexico, Colombia, and Venezuela soon broke relations. "If ever a policy paid dividends," State Department official Adolf Berle crowed, "the Good Neighbor policy has."44 The United States eventually got its way, but not as easily as Berle assumed. At a hastily convened meeting in Rio de Janeiro in January 1942, Chile and Argentina blocked a U.S.-sponsored resolution requiring the breaking of relations. The best that could be secured was an alternative recommending such a step, "a pretty miserable compromise," Hull fumed. Although most nations complied before the meeting ended, Hull remained outraged, conveniently blaming his rival Welles, who headed the U.S. delegation.45

Chile and especially Argentina held out for much of the war. With a deeply divided government and a long, indefensible coastline, Chile refused to break relations until early 1943. Far removed from the war zones, Argentina did not share U.S. preoccupation with the Axis threat. It had a large German and Italian population and Axis sympathizers within its officer corps. Traditionally, Argentines had looked more to Europe than to the United States. During the 1930s, they had repeatedly challenged U.S. leadership and resisted North American cultural hegemony. Engaged in an all-out war with enemies deemed the epitome of evil, U.S. leaders, on the other hand, had little patience with Argentina's independence, which they blamed on pro-Nazi sympathies rather than nationalism. Hull and Roosevelt resented Argentina's challenge to U.S. leadership. In Hull's mind, the dispute remained tied to the despised Welles and thus often took the form of a Tennessee mountain feud. A military takeover by Col. Juan Perón in 1944 heightened U.S. fears of fascism in Latin America. With Welles gone, Hull escalated the rhetorical warfare against Argentina and recalled his ambassador. Only Hull's retirement in late 1944 and Argentina's last-minute leap onto the Allied victory bandwagon brought a short-term resolution to the ongoing crisis. Argentina declared war just in time to secure an invitation to the 1945 United Nations conference at San Francisco.46

The United States mounted a multifaceted effort to eliminate Axis influence in the Western Hemisphere, build up defenses against the external threat, and promote hemispheric cooperation. The administration insisted that U.S. companies operating in Latin America fire German employees and cancel contracts with German agents. It blacklisted and imposed boycotts on Latin firms run by and employing Germans. With government support, U.S. businesses set out to replace the German and Italian firms driven out of business.47 The United States sent FBI agents to assist local police in tracking subversives and create counterespionage services.48 Nelson Rockefeller's Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs funded a program to combat diseases such as malaria, dysentery, and tuberculosis, especially in regions that produced critical raw materials or where U.S. troops might be stationed. Building on programs initiated by the Rockefeller Foundation, the Institute for Inter-American Affairs worked with local health ministries to improve sanitation and sewage, develop preventive medicine programs, and build hospitals and public health centers. This precursor to the Cold War Point Four program reflected the idealistic—as well as pragmatic—side of the wartime Good Neighbor policy. It won some goodwill for the United States in the hemisphere.49

With a $38 million budget by 1942, the CIAA also expanded the propaganda barrage set off before Pearl Harbor. It used various means to drive Axis influence off the radio and out of the newspapers and mounted an intensive, broad-based "Sell America" campaign. In cooperation with Latin governments, it used a blacklist of Axis films to secure for the United States a near monopoly on movies shown in Latin America. It arranged for goodwill tours by Hollywood stars such as the swashbuckling Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and the glamorous Dorothy Lamour. Under the watchful eyes of CIAA censors, Hollywood films continued to present favorable images of North Americans to Latin America and of Latin Americans to the United States. Walt Disney's cartoon "Saludos Amigos" featured a humanized Chilean aircraft that courageously carried the mail over the Andes, and a colorful parrot, José Carioca, who outtalked and outwitted the clever and acerbic Donald Duck.50

The United States used military aid and advisory programs to eliminate European military influence and increase its own. Seeking to convert the Latin American military to U.S. weapons, the administration provided more than $300 million in military equipment. Lend-lease supplies helped equip Mexican and Brazilian units that actually fought in the war and provided assorted weapons to other hemispheric nations. In cases like tiny Ecuador, where military aid could not be justified, the U.S. Army creatively displayed its newest hardware in a "Hall of American Weapons" in the national military academy.51 Fearing coups by pro-Axis military officers, the United States before Pearl Harbor began to use a carrot-and-stick approach to replacing Axis military advisers with its own. United States officials also hoped that close military ties would inculcate their own military values and thereby promote the Good Neighbor ideal and political stability. Responding to U.S. pressures, most Latin governments eased out European military missions. By Pearl Harbor, the United States had advisers in every Latin nation. Senior officers came to the United States on goodwill tours; Latin Americans attended U.S. military educational institutions, including the service academies—the sons of Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza and his Dominican counterpart, Rafael Trujillo, attended West Point.52

From the standpoint of U.S. interests, wartime policies succeeded splendidly. With Europe out of the picture, trade skyrocketed. The United States purchased huge quantities of critical raw materials, which, along with Export-Import Bank loans, helped stabilize Latin economies. At the height of the war, Latin America sent 50 percent of its exports to and received 60 percent of its imports from the United States. After 1942, active military collaboration became less crucial. Latin America's main role was to furnish air and naval bases and provide raw materials. Indeed, the U.S. military spurned full-fledged cooperation because of the demands that might result. Still, Mexico provided an air squadron to fight in the Pacific. Even more important, 250,000 Mexicans served in the U.S. armed forces, and Mexico provided a majority of the more than three hundred thousand braceros workers who helped meet an acute labor shortage in the United States. Brazil sent forces to fight in Italy and made available bases for the United States on its protruding northeast corner—the "bulge" of Brazil—a critical stopping point for U.S. ships and aircraft en route to North Africa.53 By war's end, the United States had achieved hegemony in the hemisphere without imposing its will by force.

In terms of advancing the Good Neighbor ideal, wartime policies were less successful. In an ethereal sense, so much of that spirit was tied to the charismatic persona of Franklin Roosevelt, and the spirit—and policy—barely survived his death. Once the Axis threat eased, Latin America became a lesser priority for the United States. Unfulfilled expectations led to disappointment and frustration. United States officials resented Latin displays of independence and sometimes complained that they received only a small return on their considerable investment. Latin Americans expressed disappointment at what they considered meager U.S. aid. Although they profited from wartime trade, Latin nations also suffered from chronic shortages and high inflation and worried about their growing economic dependence on the United States.54

Close contact between North Americans and Latin Americans often raised tensions. In implementing the blacklists, U.S. officials made clear they did not trust governments they considered inferior to effectively root out Axis influence. They acted unilaterally and with a heavy hand to counter a threat they grossly exaggerated. In targeting people and firms to be blacklisted, they often acted on hearsay and rumor. Latins deeply resented the infringements on their sovereignty. The Colombian foreign minister denounced the blacklist as "economic excommunication" and compared it to the Spanish Inquisition.55 In the British Caribbean nations put under U.S. control by the 1940 destroyers-bases deal, the people originally welcomed the North American presence as a means to achieve independence and prosperity. But the demeanor of superiority manifested by the occupiers and especially their efforts to impose racial segregation quickly brought disillusionment. "Maybe the American military authorities have forgotten they are not in Alabama," a Guyanese complained.56 Good Neighbor propaganda relentlessly promoted favorable mutual images but worked no more than limited changes. While generally acceding to its wishes, Latin Americans continued to resent and fear the United States; North Americans clung doggedly to old stereotypes.57

Despite the rhetoric of republicanism, U.S. wartime policies actually strengthened dictatorships and heightened oppression in many countries. Repressive governments exploited the counterespionage programs the FBI helped establish in Brazil and Guatemala to stifle internal dissent.58 The refusal to intervene that was basic to the Good Neighbor policy made it expedient to tolerate dictatorships in the name of order. Clever tyrants like Trujillo hired professional lobbyists to promote their cause in Washington and skillfully exploited the Axis threat and U.S. preference for stability to increase their military power and enhance their personal power. The military aid and advisory programs helped expand the military's power in Latin American politics. Sharing a common "military culture" that favored order at the expense of democracy, U.S. officers sometimes formed close connections with their Latin counterparts and helped buffer dictators like Trujillo against internal foes and State Department critics. Salvadorean dictator Maximiliano Martinez's bloody suppression of a 1943 internal revolt made plain the tragic human consequences of a "spoonful" of U.S. weapons—six tanks and five thousand old rifles.59 Trujillo used U.S. military aircraft and rifles to terrorize his own people and destabilize Central America. Friends of liberty in the region were "puzzled and discouraged," a State Department official reported, that the United States while fighting dictators abroad was supporting them in the hemisphere. The United States, Latin critics complained, had become a "good neighbor of tyrants."60

Concern for the hemisphere also produced renewed interest and limited wartime commitments in Liberia, a country founded by freed American slaves. West Africa's proximity to the "bulge" on the east coast of Brazil and rising Nazi influence there brought Liberia to U.S. attention before Pearl Harbor. The loss of Southeast Asian rubber heightened the importance of the enormous Firestone plantations. The invasion of North Africa increased the value of the Brazil–West Africa air route. FDR's brief post-Casablanca visit to Liberia and his flight from there to Brazil gave presidential impetus to plans already under consideration in the government. During the war, the United States began to construct an airfield in Liberia and drew up plans for a modern port at Monrovia. To sweeten the deal, it provided Liberia a $1 million grant. To promote economic development, it dispatched technical missions to evaluate Liberia's mineral resources, increase its agricultural productivity, and improve medical facilities. Deeply concerned at the Amero-Liberian elite's exploitation of the native population, FDR was prepared to insist on reforms as a condition for further U.S. aid. He even contemplated some form of trusteeship to ensure the right kind of progress. His plans were incomplete when he died in April 1945.61

While solidifying its position close to home, the United States also took the first fateful steps toward entanglement in the Middle East, a complex and volatile region that would entice and frustrate Americans for the rest of the century and beyond. Some officials naively believed that the United States had earned the goodwill of Middle Eastern people, as Hull put it, from a "century of . . . missionary, education, and philanthropic efforts . . . never tarnished by any material motives or interests."62 As Hull's remark suggests, the region was not entirely terra incognita to Americans. Missionaries had been there since the 1820s, working mainly with Christian minorities but also establishing schools and hospitals open to Muslims. Missionaries and educators founded Robert College in Turkey and the American University in Beirut. They spearheaded Near East Relief, which mounted a heroic effort to ease the vast human suffering from World War I and the breakup of the Ottoman Empire and has been called "one of the most notable chapters in the annals of American philanthropy abroad."63 Good intentions notwithstanding, most Americans placed Arab and Jew alike near the bottom of their racial hierarchy, viewing them as backward, superstitious, and desperately in need of Westernization.64 Material interests rather than ideals drove the wartime push into the Middle East. American merchants and businessmen had long been active in the region—in the twentieth century, oilmen especially so—and by 1940 U.S. firms had acquired oil concessions in Iraq, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia. The growing importance of economic interests produced a diplomatic presence. The significance of Middle Eastern oil plus increasingly insistent demands on the part of Jewish-Americans for U.S. recognition of Zionist proposals for a Jewish homeland in Palestine brought together before World War II the conflicting forces that would dominate and bedevil U.S. Middle East policy to the present.

Early in the war, the United States deferred to the British. The Middle East had traditionally been a British sphere of influence, and as long as the region was in peril militarily Americans were not disposed to challenge their ally. When the British brutally suppressed a nationalist revolt in Egypt in February 1942, the Roosevelt administration said nothing.65 It permitted Britain to distribute American lend-lease supplies to Middle Eastern nations. Even in Saudi Arabia, where U.S. oilmen hit a gusher in 1938, FDR allowed Churchill to take the lead. "This is a little far afield for us," he conceded to one of his advisers in 1941.66

United States policy changed dramatically in 1943. By this time the region was relatively secure, and the focus of war had shifted to new theaters, freeing Americans to challenge British colonialism. Exporters feared that Britain's domination of the region would close off vital postwar markets and insisted that the United States must liberate itself from British control. Critics like Roosevelt's personal emissary, the flamboyant and sometimes clownish former secretary of war Patrick Hurley—who also had close ties to U.S. oil interests—charged that Britain and the Soviet Union were using American supplies to curry favor with Middle Eastern nations. In response, the administration in 1943 took over distribution of lend-lease and marked all supplies with the U.S. flag and the words "Gift of the U.S.A." to make clear the source and thereby presumably gain full political benefit.67

The main reason for the shift can be summed up in one three-letter word: oil. With the loss of Southeast Asian supplies in early 1942, the importance of Middle Eastern oil increased. World War II made quite clear that oil was the most precious commodity in modern warfare and the essential ingredient of national security and power. The U.S. war machine guzzled voracious quantities—the Fifth Fleet fighting in the Pacific consumed by itself 3.8 billion gallons of fuel in a single year. Government studies warned in alarmist—and, it would turn out, greatly exaggerated—tones that the nation could not meet its essential postwar needs from domestic sources. It must look abroad, and in "all the surveys of the situation," a State Department official recalled, "the pencil came to an awed pause at one point and place—the Middle East."68

The shift can be seen in policies toward individual nations. In Egypt, which had no oil, America's political and military presence remained limited, but its economic influence increased significantly. Minister Alexander Kirk railed against British imperialism and pushed for an Open Door policy.69 United States investors and multinational corporations, working with conservative Egyptian elites and backed by Kirk, formed a sort of "New Deal coalition" that frustrated British neo-colonial schemes by establishing joint ventures for such projects as a huge chemical plant at Aswan on the Nile. The U.S. government helped fund the plan with a 1945 Export-Import Bank loan, marking the beginning of the retreat of British business from Egypt and the entry of U.S. firms such as Ford, Westinghouse, Kodak, and Coca-Cola.70

The United States pursued a much more vigorously independent course in Saudi Arabia. Hull described Saudi oil as "one of the world's greatest prizes." The country's strategic location between the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf offered logistical advantages for both the European and Pacific wars.71 In April 1942, the Roosevelt administration opened a legation in Jidda and sent a technical mission to advise the government on irrigation. In February 1943, it made Saudi Arabia eligible for direct lend-lease aid. Two of King Ibn Saud's sons were invited to Washington and entertained lavishly at the White House. The United States extended a sizeable loan to the Arab kingdom and sent a military mission without consulting the British.

The U.S. entry into Saudi Arabia set off a spirited—and for Saudi leaders lucrative—competition with Britain. The desert kingdom at this time had few resources and considerable needs. A man of great physical strength and an astute warrior-statesman, the fiercely independent Ibn Saud had used divide-and-conquer tactics to unite disparate tribes into the foundation of a modern state. He sought to exploit the Anglo-American rivalry to strengthen his nation and enhance his personal power. He submitted duplicate orders. When the two rivals tried to cooperate to curb his gargantuan appetite for military hardware and personal accoutrements, he hinted to each he might turn to the other. "Without arms or resources," he complained to nervous Americans, "Saudi Arabia must not reject the hand that measures its food and drink."72 An aficionado of automobiles, he extorted luxury vehicles from both nations and still whined to Americans about the lack of spare parts and the slow delivery of an automobile promised his son.73 In early 1944, Roosevelt and Churchill sought to calm rising tensions with mutual assurances about each other's stake in Middle Eastern oil. FDR averred that the United States was not casting "sheep's eyes" toward British holdings in Iran; extending the ovine metaphor, the prime minister responded that Britain would not "horn in" on U.S. interests in Saudi Arabia.74 In Saudi Arabia, however, the competition continued and, reflecting the shifting balance of economic power, became increasingly one-sided. In early 1945, Churchill sent Ibn Saud a refurbished Rolls-Royce. FDR trumped him with a spanking new DC-3 aircraft and a crew for one year, the basis for Trans World Airlines' entry into Middle East air routes.75 Saudi Arabia was the only nation for whom lend-lease was continued after the war. The United States solidified its control of Saudi oil and over strong British opposition developed plans to build an air base at Dhahran (completed in 1946) to protect those holdings.76

The wartime experience in Iran best exemplifies the illusions and frustrations of America's initial move into the Middle East. Iran possessed the region's largest known oil reserves, long dominated by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. Threatened by the Nazis in 1941, it was jointly occupied by the British and Russians, who deposed the pro-German shah and installed his son, the twenty-two-year-old Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, a retiring and in some ways tragic figure who would be a major player in postwar Middle Eastern history. Sharing British and Soviet concern about the Nazi threat, the United States acquiesced in the occupation. Iran had long survived by playing outside powers against each other. With the British and Russians working together, it turned to the United States as a buffer.

Washington responded sympathetically. United States officials recognized the strategic importance of Iran. Some also saw an opportunity for their nation to live up to its anti-colonial ideals by protecting Iran against the rapacious Europeans. FDR conceded on one occasion that he was "thrilled with the idea of using Iran as an example of what we could do by an unselfish American policy."77 The United States thus charted an independent course, furnishing lend-lease supplies directly rather than through the British and dispatching a number of technical missions to provide the know-how to assist Iran toward independence and modernization. The United States alone, a State Department official observed, could "build up Iran to the point at which it will stand in need of neither British nor Russian assistance to maintain order in its own house."78

This ambitious and ill-conceived experiment in nation-building failed miserably. It operated on the naive assumption that limited advice and assistance from disinterested Americans would enable Iran to develop the stability and prosperity to fend off predators like the Soviet Union and Britain. The U.S. Army did construct a vital supply route from the Persian Gulf to the USSR, but that project brought little immediate benefit to Iran, and the carousing and cultural insensitivity of some of the thirty thousand GIs working on it offended local Muslim sensibilities. A mission directed by Col. H. Norman Schwarzkopf, who had won national notoriety as head of the New Jersey State Police during the kidnapping of aviator Charles Lindbergh's child, achieved a "small miracle" by converting a "once bedraggled" gendarmerie into a respectable rural police force. The other missions were understaffed and poorly prepared. Few of the Americans knew the language or anything about the country. They squabbled among themselves and with the U.S. Army, losing credibility among their hosts. The most conspicuous failure was a finance mission headed by Arthur Millspaugh, who had enjoyed some success in Iran in a similar capacity in the 1920s. A poor administrator, he spoke no French or Farsi. He correctly pinpointed the problems to be addressed, but his proposed solutions and his imperious methods alienated those Iranians who profited most from the status quo and those nationalists eager for reform.79 "The Iranian himself is the best person to manage his house," nationalist leader Mohammad Mosaddeq proclaimed.80 The missions undermined the positive image the United States had brought to Iran in 1941. Iranians made them a scapegoat for the nation's problems. Designed to bolster Iran's independence, they destabilized its politics and aggravated tensions with Britain and the USSR.

The failure of the missions marked the end of the idealistic phase of U.S. policy in Iran. At Tehran in December 1943, Roosevelt persuaded Churchill and Stalin to agree to a declaration pledging support for Iran's independence. Bemoaning Soviet and British imperialism and the chaos that afflicted the American effort in Iran, the voluble Hurley urged a redoubled U.S. intervention headed by a strong-willed individual—no doubt himself. High State Department officials, on the other hand, denounced Hurley's proposal as a "classic case of imperial penetration," an "innocent indulgence in messianic globaloney."81 Roosevelt seemed interested, but his attention quickly shifted to other matters and he rejected Hurley's proposal.

By this time U.S. policy in Iran was undergoing major change. The relentless push for concessions in Iran drove the major oil companies and the U.S. and British governments toward cooperative arrangements to stabilize international production and distribution. The Anglo-American Petroleum Agreement of 1944 infuriated small U.S. producers and was never approved by Congress, but it eased temporarily the fierce rivalry in Iran. More important, a Soviet move for an oil concession in northern Iran in 1944 increasingly brought two formerly bitter rivals together. Both British and U.S. diplomats viewed Moscow's ploy not as a response to U.S. efforts to gain oil concessions in Iran but as a power play to expand its influence into the Persian Gulf. If not yet working together, Britons and Americans increasingly agreed on the need to check the Soviet threat. No mere puppet, the Iranian government itself resolved the immediate crisis and protected its future interests by refusing to approve any oil concessions until the war ended.82

By 1943, that other inflammatory ingredient of an already volatile Middle Eastern mix had also come into play. The Zionist quest for a Jewish homeland in Palestine emerged late in the nineteenth century out of desperation—and hope—on the part of Europe's persecuted and dispossessed Jews. The idea gradually gained support among America's large and increasingly influential Jewish community. When World War I set off a bidding war between the Allies and the Central Powers for Jewish support, the Zionist dream first gained international recognition. The British-sponsored Balfour Resolution of 1917, perfunctorily supported by Woodrow Wilson, pledged carefully qualified backing for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. With the rise of a new wave of anti-Semitism in the 1930s, especially in Nazi Germany, immigration to Palestine soared, sparking violent resistance from native Arabs. Fearful on the eve of war of a dangerous conflict in a strategically critical area, Britain in 1939 issued a white paper drastically curtailing Jewish immigration to Palestine and then shutting it down after five years. The white paper solved little. Arabs doubted its assurances; Jews mobilized to fight it.83

The drive for a Jewish homeland became linked in wartime with the unfolding horror of Hitler's Final Solution. As early as the summer of 1942, word began to filter out of Europe of the establishment of death camps and the systematic killing of European Jews. The initial reports did not begin to capture the enormity of the atrocities, but many Americans, insulated from direct contact with the war, questioned them nonetheless. Even when the magnitude of the extermination began to emerge, the administration could do little. FDR publicly condemned the killing of Jews and vowed to conduct war criminal trials to hold the perpetrators accountable. To take the matter out of the hands of an unsympathetic State Department, he created in 1943 a War Refugees Board that enjoyed some success helping Hungarian Jews escape Nazi grasp. But the president refused, with the war still far from won, to challenge Congress by seeking to ease immigration restrictions. And the War Department rejected proposals to bomb the death camp at Auschwitz on grounds that it would accomplish little and divert crucial resources from "essential" military tasks. The pragmatic U.S. response to a great moral catastrophe is somehow unsatisfying. But it is far from clear that any of the courses proposed to deal with the Holocaust could have been effectively implemented or would have saved significant numbers of lives.84

As the magnitude of Hitler's atrocities began to emerge, Zionists stepped up their agitation for a homeland, and sympathy tinged with some measure of guilt brought growing support. Many Americans also saw large-scale immigration of Jews to Palestine as preferable to swelling their already sizeable numbers in the United States. At New York's Biltmore Hotel in May 1942, Palestinian Jewish leaders such as David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann inspired a gathering of Jewish-Americans to support unlimited immigration into Palestine and the creation of a "Jewish Commonwealth integrated into the structure of the new democratic world."85 The Biltmore group mounted a massive and effective campaign to sway Congress and the American public.

Caught between Arab fears and Jewish demands, the Roosevelt administration handled a volatile issue like a ticking time bomb. The president had made Jewish-Americans an integral part of his New Deal coalition and relied on their electoral support. In the State Department and other federal agencies, on the other hand, there was virulent anti-Semitism. Most important, the question of a Jewish homeland threatened to upset the delicate political balance in a critical region. GIs had already come under fire in Palestine, and military leaders feared that Jewish agitation could spark further conflict in an important rear area. At a time when U.S. attention was focused on the Middle East to meet presumably urgent demands for oil, the Palestine issue threatened to upset the Arabs who controlled it. Ibn Saud prophetically warned Roosevelt in 1943 that if the Jews got their wish, "Palestine would forever remain a hot bed of troubles and disturbances."86 FDR at times fantasized about going to the region after leaving the presidency and promoting economic development projects like the Tennessee Valley Authority. He expressed confidence that he could resolve the dispute in face-to-face conversations with Arab leaders. Characteristically, the administration dealt with the most pressing issues with pleas for restraint, platitudes, and vague assurances to both sides. A master of the latter, FDR, after assuring Ibn Saud in 1943 that he would do nothing without full consultation, concluded the following year—at election time—that Palestine should be for Jews alone.87 During the campaign, while fending off a congressional resolution favoring a Jewish homeland, he promised to help Jewish leaders find ways to establish a state.

For Roosevelt, the last act in the unfolding drama came in February 1945 en route home from the Yalta Conference when he met Ibn Saud at Great Bitter Lake north of the Suez Canal. The king was transported there by a U.S. destroyer, traveling in a tent pitched on deck (U.S. sailors called it the "big top") with an entourage of forty-three attendants and eight live sheep to meet requirements of Muslim laws for preparing food. Much impressed with Ibn Saud, FDR labeled him a "great whale of a man" and left a wheelchair for the battle-scarred warrior's use. The president hoped to persuade the king to acquiesce in a Jewish homeland. What he got was adamant opposition to further Jewish settlement—even to the planting of trees in Palestine. "Amends should be made by the criminal, not by the innocent bystander," he told FDR, proposing instead a Jewish homeland in Germany. Taken aback, Roosevelt pledged in typical fashion that he would "do nothing to assist the Jews against the Arabs and would make no move hostile to the Arab people." His subsequent public statement that he had learned more from Ibn Saud in five minutes than from countless exchanges of letters struck fear in Zionists allayed only in part by subsequent soothing reassurances.88 The Middle East took a backseat to more pressing issues in the last stages of the war. By virtue of its rising power and emerging interests, however, the United States had taken a keen interest in the region and through oil and Palestine had become caught up in a hopelessly intractable dispute.

A powerful undercurrent in the Middle East, the issue of colonialism dominated U.S. involvement with South and Southeast Asia. Held in check in the 1930s by brute force and token concessions, nationalists quickly saw in the war a chance to gain their freedom. They read carefully and literally the 1941 Atlantic Charter and found in it sanction for their cause. Japan's sweep through Southeast Asia in 1942 graphically exposed the weakness of colonial regimes. In some areas, the new rulers imposed a more cruel and oppressive rule than the Europeans, but their cry of "Asia for Asians" resonated with local nationalists. Because of its power and its anti-colonial tradition, nationalist leaders looked to the United States for support. Like it or not, the Roosevelt administration found itself ensnared in the complex historical process of decolonization that would dominate world politics for years to come.

The colonial issue was among the most challenging of the myriad complex problems raised by the war. Many Americans were firmly committed to Wilson's dream of self-determination. African Americans in particular saw a direct connection between the oppression of peoples of color at home and abroad and pushed for an end to both.89 The colonial issue became in the eyes of Americans and peoples across the world a test case for the nation's commitment to its war aims. At the same time, many U.S. officials doubted, usually on the basis of racial considerations, that colonial peoples were ready for self-government and feared that premature independence could lead to chaos. They also worried that to force the issue of independence during the war could undermine crucial allies like Britain and threaten Allied cooperation when the outcome of the war remained uncertain.

Roosevelt's handling of the issue is typically difficult to decipher. He often railed against European colonialism—Britain, he once snarled, echoing John Quincy Adams, "would take land anywhere in the world even if it were only a rock or sand bar."90 At a Casablanca conference dinner, while Churchill chomped angrily on his cigar, FDR raised with the sultan of Morocco the possibility of independence. On the other hand, he shared the assumptions of his generation that most colonial peoples were unready for independence and would need guidance from the "advanced" nations. Critics have correctly noted that his often bold rhetoric was not matched by decisive actions. He refused to demand of the colonial nations forthright pledges of independence. As Kimball has emphasized, on the other hand, he was utterly Wilsonian, and correct, in his assessment that colonialism was morally reprehensible—and doomed. Ever the pragmatist, he refused to jeopardize the alliance by mounting a frontal assault on colonialism. At the same time, he kept the issue on the front burner, bringing it up often, using various means to nudge the colonial powers in the right direction, apparently hoping that what he called the glare of "pitiless publicity" (turning Churchill's own words against him) would promote international support for independence.91

In the first years of the war, India was the most visible and emotional of decolonization issues, and it clearly reveals Roosevelt's approach. Under the leadership of the saintly Mahatma Gandhi, Indian nationalists had pushed the British toward self-government, and they seized the emergency of war to press for pledges of independence. Many British leaders, including the arch-imperialist Churchill, were not prepared to abandon the crown jewel of an empire on which it was once said the sun had never set. They in turn used military exigencies and the threat of communal warfare between Hindus and Muslims as excuses to delay, offering no more than vague promises of "dominion status" once the war had ended.92

India quickly became the major irritant in the Anglo-American partnership. Even before Pearl Harbor, the United States had given symbolic support to India's appeals for independence by establishing direct diplomatic relations with the colonial regime. It insisted that lend-lease aid be sent directly to the Indian government rather than through the British. At their first wartime meeting in January 1942, Roosevelt prodded Churchill to pledge support for eventual Indian independence. By his own account, the prime minister exploded, and the president never again raised the issue with him directly. But FDR continued to needle Churchill through third parties ranging from Hopkins to Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek. He insisted that the government of India sign the United Nations Declaration. At various stops on a world tour taken at the president's behest, Wendell Willkie denounced imperialism. In China, he pressed the colonial powers to set a timetable for independence. Over and over, the president offered U.S. mediation between Britain and Gandhi's nationalists.