On November 11, 1983, millions of Americans gathered around their television sets to watch The Day After, a chilling account of the impact on ordinary people of a nuclear attack on the middle-American town of Lawrence, Kansas. Unbeknownst to these viewers, several days earlier, in response to NATO's annual Able Archer military exercises, a nervous Soviet government, convinced that a nuclear attack was imminent, went on full alert and put its nuclear-capable aircraft on standby. The world had come "frighteningly" close to the nuclear abyss, a Soviet defector later recalled.1

Incredibly, less than five years after this second most dangerous Cold War flash point, hard-core anti-Communist U.S. president Ronald Reagan and Soviet general secretary Mikhail Gorbachev strolled leisurely through Moscow's Red Square and declared themselves "old friends." When queried regarding his earlier, belligerent statements about the Soviet Union, Reagan dismissed them as from "another time, another place." Within three more years, the Communist governments in Eastern Europe had fallen, the Berlin Wall had been torn down, the Cold War declared ended, and the Soviet Union had collapsed. This swift and stunning transformation of the international system without war or violent revolution was without precedent. Reagan's successor, George H. W. Bush, aptly called it "a unique and extraordinary moment."2

Many Americans have been quick to claim credit for these breathtaking changes. It was the power of their ideals, they insist, that toppled the Iron Curtain; the skill and strength of their policies, particularly under Reagan, that won the day. In this tale of virtue and heroism, Reagan's principled and outspoken stand against Communism and his massive defense buildup forced Soviet capitulation and won the Cold War.3 There is, of course, some truth in such arguments. America's ideals—and even more, its popular culture—did influence people around the world. Reagan played an important role. But his policies were never as clear-cut as his proponents claim. They were often sloppily implemented. In the early years, they dangerously exacerbated Cold War tensions. It was only when he shifted toward conciliation that they began to produce results. His successor, George Bush, had the good sense to let history take its course. It is essential to look beyond the United States to comprehend the stunning transformation of 1981–91. More than anything else, it was the basic weakness of the Soviet system and the dramatic steps taken by the remarkable Gorbachev that produced these striking changes.

Ronald Wilson Reagan looms over the last quarter of the American Century as Woodrow Wilson the first and Franklin Roosevelt the second. Unlike Wilson, the former movie actor contributed nothing to the intellectual content of U.S. foreign policy. But like FDR, the hero of his youth, he touched the American psyche as few other politicians have. He restored the American spirit, scarred by Vietnam and Watergate and afflicted by a loss of confidence and self-esteem. He revived and gave eloquent expression to a messianic vision that resonated with Wilsonianism. Whether by luck or skill or some elusive combination of both, he presided over a rebirth at home and transformation abroad that set the stage for the end of the Cold War and America's emergence as a global power with a position of primacy unmatched since the days of Victorian England.

Reagan's life embodied the American dream, and therefore, perhaps naturally, he became one of its foremost exponents. A product of smalltown midwestern America, often viewed as the quintessence of the nation, the young man known as "Dutch" first achieved notice in the 1930s by broadcasting over radio to regional households baseball games whose details he acquired by teletype. Sometimes, when the machine broke down, he made up the play-by-play as he went along. He moved easily from one form of media to another, starring in a series of B movies during the war years and after. A New Dealer, he anticipated the national shift to the right by adopting a fiercely anti-Communist position during 1950s investigations of leftist activities in Hollywood. He gained national prominence, wealth, and important political contacts as host for a popular television program and spokesperson for General Electric. He stirred the passions of conservatives in 1964 with a powerful speech supporting Goldwater for president. Undaunted by the Arizonan's disastrous defeat, in 1966 he unseated Edmund "Pat" Brown, the popular Democratic governor of California, launching a political career that after several setbacks led to the White House. By the time he went to Sacramento, he had put on full display the qualities that would make him an icon: rugged good looks; a genial and amiable disposition; and a mellifluous, soothing voice that earned the trust of his listeners. He had an instinctive feel for the mood of the American people. His sunny optimism was perfectly calculated to heal a wounded nation. Better than anyone else since John Kennedy, he articulated the nation's ideals and hallowed myths.4 "Reagan's rhetoric wove a seamless tapestry of 'morality, heritage, boldness, heroism, and fairness' that offered a compelling, if rather fanciful, vision of a genuine national community," Richard Melason has written.5

Reagan brought to the presidency no foreign policy experience but deeply felt views. He had preached throughout his political career unrelenting opposition to Communist tyranny. He deplored the so-called Vietnam Syndrome that had allegedly sapped the United States of its sense of purpose and the defeatism and malaise that stamped the Carter years. Looking nostalgically to the days when the United States had been number one in the world, he sought to restore a position he thought had been squandered by lack of courage and will. He promised to rebuild the nation's faltering economy and its military arsenal to confront Communist adversaries and especially the USSR from a position of strength. Like the Committee on the Present Danger, he vowed to go beyond mere containment by exposing the evils of Communism, exploiting the Soviet Union's internal weaknesses, and backing insurgencies that aimed to overthrow leftist governments, thereby altering the status quo in America's favor.

The Reagan foreign policy was more complex than might appear on the surface, however. The president preferred people of action to intellectuals. But his idealism and instinctive unilateralism were tempered by a touch of pragmatism, the mainstream Republican internationalism espoused by secretaries of state Alexander M. Haig Jr. and George Shultz, and the hard-nosed Machiavellianism of CIA director William Casey. Reagan and the Californians who comprised his White House staff were in the most basic sense unilateralists. They knew little about the rest of the world. They had no faith in the United Nations and other international institutions. In his view of America, the president himself was a veritable Woodrow Wilson in greasepaint. He accepted as an article of faith the myth of American exceptionalism and repeatedly evoked John Winthrop's imagery of a "city on a hill," which he usually embellished by adding the adjective "shining." He had no doubt of the superiority of American ideals and institutions and was certain the rest of the world awaited them. He was also a throwback to Teddy Roosevelt. His code name Rawhide symbolized the western hero that he played in movies and that to him epitomized the nation. He believed the United States must have the courage of its convictions and be willing to fight for its ideals. But he was also a pragmatist.6 As much as he deplored the Vietnam Syndrome, he recognized the deep-seated popular fears of military intervention abroad. His often bellicose rhetoric was moderated by caution in the use of power.

Reagan's unilateralist and messianic tendencies were also balanced by Haig and Shultz. The secretaries of state shared his anti-Communism and belief in a strong defense, but they were also committed to close cooperation with America's European allies and were more willing to negotiate with the Soviet Union and China. Casey on the other hand, shared the president's anti-communism and his penchant for action. Apparently with Reagan's blessing and sometimes without the knowledge of Shultz, he developed a worldwide program of covert operations to undermine Communist governments.7

Confusion of concept was joined by chaos in implementation. Reagan was grandly indifferent to detail. He often displayed a careless disregard for unpleasant facts and sometimes appeared to live in a Hollywood-like fantasy world. He was the sloppiest administrator since Franklin Roosevelt. His White House staff was totally inexperienced in foreign policy, and amateur night was a regular occurrence. Theoretically the orchestrator of foreign policy, the National Security Council—by design—was plagued by weakness and chronic instability. Reacting against the dominant role played by Kissinger and Brzezinski, the president's team deliberately downgraded the NSC and appointed lesser lights to head it. Reagan had six different national security advisers in eight years.8

Conflict within the administration made the Vance-Brzezinski feud look like a love feast by comparison. Paraphrasing Air Force Gen. Curtis LeMay, hard-line NSC staffer Richard Pipes observed that while the Soviets were the adversary, "the enemy was State." For its part, Haig's State Department refused to share important documents with NSC.9 Reagan was isolated from the NSC by White House advisers and his wife, Nancy, who feared that the ideologues who staffed it would reinforce his hardline tendencies. Haig's efforts to crown himself the "vicar" of Reagan's foreign policy earned him the enmity of the White House staff, who sarcastically dubbed him CINCWORLD (commander in chief of the world)—and eventually got him fired. For more than six years, Shultz and Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger waged as acrimonious a power struggle as ever seen in Washington over such issues as arms reduction, the proper response to terrorism, and the employment of U.S. military forces abroad. The NSC staff and Casey conducted operations bitterly opposed by both Shultz and Weinberger—when they knew about them. The policy process suffered from an excess of democracy, James Baker later recalled, "a witches' brew of intrigue, elbows, egos, and separate agendas."10 The most detached chief executive since Calvin Coolidge—whose portrait was restored to a place of prominence in his White House—Reagan refused to adjudicate the nasty disputes among his subordinates. He presided amiably over the chaos, reaping the whirlwind only in his second term when the ill-conceived and in some cases illegal shenanigans of his subordinates nearly made him a lame duck before his time. It was only in the last two years of his second term, following the Iran-Contra scandal, that some order was imposed on the policymaking process.

The Reagan policies reflected these conflicting forces. Anti-Communism was a constant. But the president's tough and occasionally bombastic talk was belied by a growing willingness to negotiate with the Soviets. Moreover, although the administration spoke loudly and through its massive arms buildup carried a big stick, it was generally cautious in sending military forces abroad. The major innovation was the so-called Reagan Doctrine, a policy of using covert arms shipments to change the status quo in favor of the "free world." In that sense alone, it departed sharply from the policies of its predecessors.

The results were mixed. The Reagan administration engaged the United States in new and dangerous ways in the ever volatile Middle East. A not-so-covert war in Central America inflicted great destruction on that troubled region and came a cropper in the Iran-Contra scandal, for a time crippling the administration in its second term. On the positive side and to the dismay of his longtime conservative supporters, Reagan established the basis for a new relationship with the Soviet Union.

During the first term, the Cold War reescalated to a level of tension not equaled since the Cuban missile crisis. This process began with Carter, of course, but Reagan went well beyond his predecessor, openly repudiating detente and reasserting the moral absolutes of the Cold War as no one had since John Foster Dulles. Indeed, in the early years, Reagan seems to have reveled in unleashing verbal cannon shots against the Soviets. In a 1983 speech to Christian evangelicals, borrowing a phrase from the blockbuster 1977 movie Star Wars, he branded the Soviet Union "the evil empire" and accused it of being the "focus of evil in the modern world."11 Moscow reserved for itself the right to "commit any crime, to lie, to cheat" to achieve its sinister goals, he said on another occasion. He once dismissed Marxism-Leninism as a "gaggle of bogus prophecies and petty superstitions" and predicted, correctly as it turned out, that communism would be remembered as a "sad and rather bizarre chapter in human history." He condemned the Soviets for shooting down a South Korean airliner in September 1983—an episode that revealed more about their nervousness and inept air defenses than their hostile intentions—insisting with no proof, and incorrectly as it turned out, that they knew all along it was a civilian aircraft. The president may have revealed his deepest instincts when he jokingly—and inadvertently—broadcast into an open radio microphone in August 1984: "My fellow Americans, I am pleased to tell you today that I've signed legislation that will outlaw Russia forever. We begin bombing in five minutes."12

During the first term, tough talk was sometimes backed by actions. The administration in 1981 threatened sanctions if the USSR used military force to put down mounting unrest in Poland. When the Polish government itself responded by instituting martial law—a "gross violation of the Helsinki Pact," Reagan raged—the United States on Christmas Eve 1981 imposed sanctions on Poland.13 Ironically, although the Soviet Union had not used force, the administration subsequently placed sanctions on it as well, terminating Aeroflot flights to U.S. cities, refusing to renew scientific exchange agreements, and in June 1982 banning the sale of equipment and technology for construction of a Soviet gas pipeline to Western Europe, an action taken without consulting European allies that outraged them. In a move that at least bordered on pettiness and spite, the administration revoked Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin's special parking place in the State Department garage.

From the beginning, however, the administration also displayed a pragmatic streak in dealing with the "evil empire." To appease U.S. farmers and satisfy his personal predilection for free trade, Reagan shortly after taking office scrapped Carter's embargo on grain shipments to the USSR. The administration's first major statement of Cold War strategy, National Security Decision Directive 75, approved in December 1982, was a compromise between hard-liners in the NSC and pragmatists in the Pentagon and the State Department. The United States would stand firmly against Soviet expansion. It would go beyond mere containment by using any means at its disposal to alter the Kremlin's behavior by inflicting costs that might exacerbate internal problems, increase reformist tendencies, and even bring about regime change. At the same time, the United States would negotiate agreements with the Soviet Union that served its interests.14

On crucial issues such as arms control, the administration in its early years was demonstrably hard-nosed. Here also, more than he was willing to admit, Reagan expanded on precedents set by Carter. Although he agreed to abide by its restrictions, he refused to resubmit to the Senate a "fatally flawed" SALT II agreement that did not provide for reductions in the two sides' nuclear arsenals. Even more than his predecessor, he rejected the doctrine of mutual assured destruction in favor of a strategy of deterrence through military superiority. Having used to advantage in the 1980 campaign the alleged "window of vulnerability" opened by a sustained Soviet buildup of nuclear and conventional weapons, the president vowed to seek "peace through strength." Ignoring campaign pledges to cut the federal budget, his administration expanded on Carter's huge buildup, increasing defense spending by 7 percent a year between 1981 and 1986. The cost was $2 trillion in the first six years and produced Pentagon spending estimated at an incredible $28 million an hour. It provided for major improvements in existing missiles and delivery systems, the addition of new systems such as the MX mobile land-based missile with ten independently targeted warheads, the humongous B-1 bomber that Carter had rejected, a six-hundred-ship navy capable of attacking Soviets ports in the event of war, and expanded salaries and benefits for military personnel.15 The buildup even revived emphasis on civil defense, this time in the form of plans to shift people from cities to small towns in time of nuclear crisis.16

In part to mute increasingly outspoken anti-nuclear protest in the United States and Western Europe, the administration evinced a willingness to talk with the Soviets, but the positions it took raised doubts about its eagerness for substantive negotiations. The appointment of hard-liners to key positions reflected its approach. As a staff aide to "Scoop" Jackson, Richard Perle had wreaked havoc with SALT; as Reagan's assistant secretary of defense for international security policy, he was in a position to shape policy. Ironically, and especially revealing, Cold Warrior Paul Nitze, the author of NSC-68, became known as the Reagan administration's arms control dove!

On the two major issues of intermediate nuclear forces (INF) stationed in Europe or aimed at Europe and longer range strategic weapons, the Reaganites insisted on much larger cuts in Soviet forces than their own. In the INF negotiations, they set forth a so-called zero option, agreeing not to deploy Pershing and Tomahawk missiles in Europe if the Soviets would dismantle their SS-20 intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs, missiles with a range of 1,865 to 3,420 miles) and other intermediate-range missiles aimed at Western Europe. British and French missiles were exempted. The zero option also left out all sea- and air-based missiles, where the United States had a huge advantage. It was "loaded to Western advantage and Soviet disadvantage," Raymond Garthoff has concluded, "and it was clearly not a basis for negotiations aimed at reaching agreement."17 When Nitze and his Soviet counterpart, after a secret July 1982 "walk in the woods," actually came up with a compromise, Perle and the hard-liners sabotaged it. Public U.S. statements that nuclear war was both feasible and "winnable" caused a furor in Europe and nervousness in the USSR.18 Deployment of intermediate-range missiles in Europe in late 1983 provoked the Soviets to walk out of the talks. The result was the most contentious and least constructive arms control talks in many years.19

The two sides fared no better with strategic weapons. In this area, the administration sharply departed from its predecessors, abandoning arms limitation for reduction—especially on the Soviet side. The new acronym START (Strategic Arms Reduction Talks) signified the change. After months of bitter internal wrangling, the United States finally adopted a negotiating position. While setting as the eventual goal the reduction of warheads to five thousand on each side, it demanded substantial decreases in Soviet warheads and land-based launchers while leaving its own cruise missiles, bombers, and submarines unaffected. "You want to solve your vulnerability problem by making our forces vulnerable," a Soviet general complained. In the lengthy discussions that followed, the United States backed off only slightly, provoking charges of "old poison in new bottles."20

Reagan complicated matters still further with a bombshell speech in March 1983 proposing a Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), a missile defense system employing lasers from space-based platforms that could intercept and destroy enemy missiles before they struck U.S. or allied soil. Controversial nuclear physicist, father of the hydrogen bomb, and ardent Cold Warrior Edward Teller first suggested the idea to the president in the fall of 1982. Reagan latched on to it with the unshakable faith that was an essential part of his being. It appealed to his longstanding and visceral hatred for nuclear weapons and the whole idea of MAD, which accepted Cold War stalemate—and which, he believed, the Soviets could not be trusted to adhere to. His enthusiasm may have been fed by a 1940 movie, Murder in the Air, in which he played FBI agent Brass Bancroft and U.S. scientists developed a secret weapon to neutralize enemy planes. He inserted the proposal into his speech before any discussion with allies and without full vetting from the bureaucracy—indeed, against the opposition of many top defense officials. He offered SDI to Americans as a "vision for the future," a way to render nuclear weapons "impotent and obsolete" and "offer hope for our children in the 21st century."21

SDI proved a typically Reaganesque stroke of political genius. Scientists and many national security experts promptly dismissed it as outrageously costly and wildly impractical and dubbed it "Star Wars" to highlight its chimerical nature. But it also touched a responsive chord with the public. Reagan shrewdly couched his appeal for SDI as a way to restore the sense of security Americans had enjoyed before World War II. He affirmed that the technological genius that had made the nation great could be used to keep it safe. By repeatedly and eloquently stressing that the United States would not exploit its invulnerability to the detriment of others—it would never be the aggressor—he played to Americans' traditional belief in their innocence. The SDI proposal immediately shifted the agenda of the national security debate, undercutting an international movement to freeze nuclear weapons at existing levels. Reagan's public approval ratings soared. SDI encouraged public support for the rest of his enormously expensive defense program. It helped secure his reelection in 1984.22

SDI also intensified already pronounced Cold War tensions. It infuriated and alarmed Soviet leaders by raising the possibility that the United States could create a partially effective missile defense system that would give it a first-strike capability. At the end of 1983, the so-called Year of the Missile, for the first time in more than fifteen years, the two nations were not discussing arms control in any forum. By this time, Soviet-American relations had descended to their lowest point in years. Fears of nuclear Armageddon had risen to their highest level since the Cuban missile crisis. In Western Europe and the United States, concern about nuclear war rose in proportion to the failure of the arms control talks. The Soviets were increasingly agitated by Reagan's inflammatory rhetoric, U.S. handling of arms control negotiations, and especially SDI. American officials expressed outrage at the September 1 downing of the South Korean airliner, bitterly denouncing what they saw as a deliberate Soviet move. This incident "demonstrated vividly," Garthoff has written, "how deeply relations between the two countries had plunged. Each was only too ready to assume the worst of the other and rush not only to judgment but also to premature indictment."23 Later that month, a Soviet satellite mistakenly picked up the approach of five U.S. missiles, triggering a full nuclear alert. Perhaps only the bold and timely intervention of a forty-four-year-old lieutenant colonel who suspected an error and overrode the computers averted a counterstrike that could have killed as many as one hundred million Americans.24 In the tense and conflict-ridden atmosphere of late 1983, only a fool would have predicted that within five years the two Cold War combatants would be negotiating major arms reduction agreements and within ten years the epic struggle would have ended.

Reagan's diplomacy was at its worst in the Middle East. United States policies lacked clear direction and purpose. They were often naive in conception and amateurish in execution. They veered between intervention and abstention. Designed on occasion to demonstrate America's toughness, they frequently underscored its weakness. The best that can be said is that the administration had the good sense—belatedly—to disentangle from a hopeless mess in Lebanon and to avoid rash actions elsewhere.

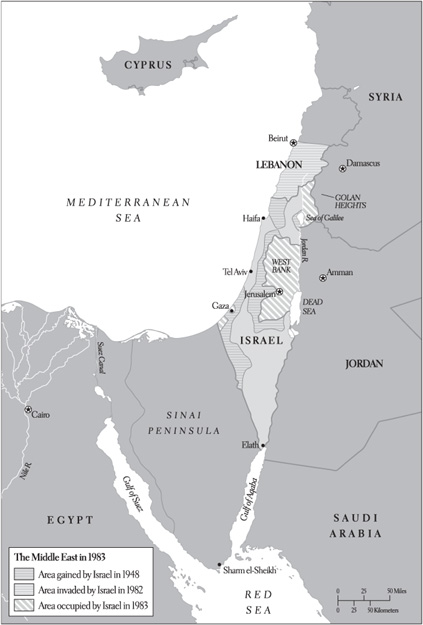

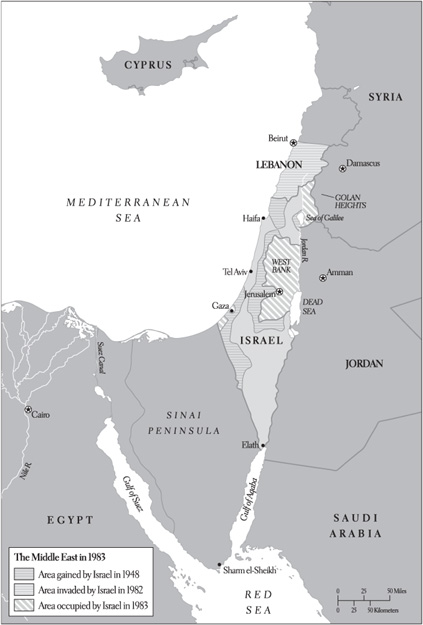

The tone was established at the outset. More divided on the Middle East than on any other issue, U.S. officials could not agree where to go with the Camp David peace process inherited from Carter. They therefore decided to put the Arab-Israeli dispute on hold. A "Hollywood pool-side Zionist," in the words of David Schoenbaum, Reagan had long admired Israel's steadfast defense of its sovereignty. As an actor and rising politician, he had supported fair treatment of Jews. He had also become a spokesperson for an emerging group of zealously pro-Israel evangelical Christians. Thus, not surprisingly, the administration set out to revive the special relationship with Israel and repair the damage done by Carter's alleged evenhandedness. But its main concern in the Middle East, as elsewhere, was the Soviet Union. In the words of a top State Department official, the Arab-Israeli conflict should be put in a "strategic framework that recognizes and is responsible to the larger threat of Soviet expansionism." Ignoring the messy realities of Middle Eastern politics, Reagan officials reasoned that since Israel, Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia were all friends of the United States, they could be united in a "strategic consensus" to check Soviet advances in a vital region.25

The scheme was doomed to fail. The administration's proposed sale of advanced AWAC aircraft to Saudi Arabia to help defend against Iran and Iraq unleashed the full fury of the Israel lobby. Only after a prolonged and at times nasty debate did the Senate in late October approve the sale by a mere two votes. To appease Israel, the administration offered a memorandum of understanding providing for large U.S. purchases of Israeli products, joint military exercises, and "readiness activities." These moves antagonized the Arabs. In June 1981, Israeli jets bombed Iraq's Osiraq nuclear installation, a step that U.S. officials may have secretly applauded and even abetted but that had been taken without consultation and thus aroused concern about the consequences of Israeli independence. More seriously, despite U.S. appeals for restraint, Israel in December annexed the Golan Heights, an area it deemed essential to defend against Syria. The administration responded by rescinding the memorandum of understanding and shutting off military aid. "What kind of talk is this—'penalizing' Israel?" Prime Minister Menachem Begin snarled. "Are we a banana republic?" Begin answered his own question six months later, again over U.S. protests, by invading Lebanon. "Boy, that guy makes it hard for you to be his friend," a befuddled Reagan moaned.26 By then, U.S.-Israeli relations were as strained as at any time in years. America's Arab friends held it responsible for Israeli aggression. The strategic consensus collapsed amidst Middle Eastern recriminations. By late 1982, the administration was moving back toward the Camp David Accords.

A crisis in Lebanon thwarted any new initiatives. Using a terrorist assassination attempt against its ambassador to Britain as the pretext for a move it had long been considering, Israel in June 1982 invaded neighboring Lebanon to eliminate Syrian influence, strike a "knockout blow" against Yasser Arafat's Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) based there, and establish a friendly Christian government. The attack came during a lull in terrorist activities and at a time when the threat to Israel had eased. It brought worldwide condemnation. The reaction was even more hostile when Israeli units drove into Beirut, igniting the powder keg of hatreds that was Lebanon. What Israel had hoped would be a quick and decisive strike became a quagmire, a modern nation with the most up-to-date military hardware combating fifteen thousand guerrillas in a city of one half million people in a war it could not win.27

Lebanon became for the United States, in the words of Reagan biographer Lou Cannon, a "case study of foreign policy calamity," a "catastrophe born of good intentions."28 If it had not given Israel the go-ahead, the administration had at least left the light blinking a bright yellow. In the aftermath, reading from note cards, a coolly detached Reagan could do little more than scold an unrepentant Begin. To make the best of a bad situation, a deeply divided administration, without careful analysis or preparation, more or less adopted Israel's goals as its own, seeking to use the invasion to get Soviet-backed Syria out of Lebanon, weaken the PLO, make Lebanon genuinely independent, and persuade it to sign a peace treaty with Israel. The United States staunchly backed the efforts of Amin Gemayel to establish an independent Lebanese government. For the first time Reagan got tough with Begin, insisting that Israel stop bombing the Palestinians while they were withdrawing. "Menachem, this is a holocaust," he berated the Israeli leader. "Mr. President, I think I know what a holocaust is," Begin sarcastically retorted.29 At the urging of new secretary of state George Shultz and over the vigorous objections of Weinberger and the military, Reagan, without a clear idea what they were to accomplish or how they would go about it, agreed in July 1982 to send a detachment of eight hundred U.S. Marines to join a multinational peacekeeping force in Lebanon.

"Lebanon is a harsh teacher," Middle East expert William Quandt has written. "Those who try to ignore its harsh realities . . . usually end up paying a high price."30 As many as twenty-five armed factions waged unrelenting war with each other in a country made up of a bewildering array of political, religious, and ethnic groups: Maronite and other Christians, Sunni and Shiite Muslims, fierce Druze mountain tribesmen, an offshoot of the Shi'as, seventeen different sects in all. Arrival of U.S. forces in August 1982 was followed by a deceptive calm, but the country soon exploded. Israel sent Christian militia into West Beirut to root out remaining elements of the PLO, causing a bloody massacre of a thousand Palestinians that further destabilized Lebanon, drew widespread international criticism, and discredited both Israel and the United States. Supporting the ineffectual Gemayel plunged the United States into the middle of a hopelessly complicated civil war. In April 1983, a terrorist bomb blew up the U.S. embassy in Beirut, killing seventeen Americans. The United States responded with air attacks and naval bombardment against locations suspected of harboring terrorists. Withdrawn to their ships after their apparent initial success and then sent back into the maelstrom, the marines, now 1,400 strong, found themselves in the late summer of 1983 hunkered down in the midst of intense and hopelessly confused fighting in Beirut. In the early morning hours of October 23, 1983, a truck bomb with the explosive force of twelve thousand tons of TNT, the largest non-nuclear blast to this time, destroyed marine headquarters, killing 241 of its sleeping occupants. The normally buoyant Reagan recalled it as the "saddest day of my presidency, perhaps the saddest day of my life."31

The bloody Sunday in Beirut ended the Lebanon intervention. Critical of the operation from the start, Weinberger and U.S. military leaders pushed for immediate evacuation of the marines. Shultz urged that they stay, and Reagan was reluctant to be pushed out. The administration thus set out to extricate them without losing face. It skillfully used the contemporaneous and successful invasion of tiny Grenada in the Caribbean to distract attention from the humiliation and grief of Beirut. But as the Lebanese army collapsed and pressures at home mounted for withdrawal, U.S. officials had little choice but to liquidate an ill-conceived venture. In February 1984, the marines were "redeployed" to their ships. Spokespersons now downplayed the importance of a country to which just recently they had attached the greatest significance. The United States had stuck "its hand into a thousand-year-old hornet's nest with the expectation that our mere presence might pacify the hornets," Army Col. Colin Powell, a top military adviser to Weinberger, later recalled.32

Powell and his boss immediately set out to prevent such deployments in the future. Over the next year, the two of them crafted a long list of conditions under which U.S. forces should be deployed. What came to be called the Weinberger or Powell Doctrine was an immediate response to the debacle in Lebanon and also to the secretary of defense's nasty, ongoing feud with Shultz over the commitment of military forces abroad. Weinberger later conceded that it also reflected the "terrible mistake" of sending forces to Vietnam without ensuring popular support and providing them the means to win. Made public in late 1984, the "doctrine" provided that U.S. troops must be committed only as a last resort and if it was in the national interest. Objectives must be clearly defined and attainable. Public support must be assured, and the means provided to ensure victory. The doctrine provoked a bloody fight within the Reagan administration—Shultz labeled it the "Vietnam Syndrome in spades." It was never given official sanction. But top military officers staunchly supported it, and as Joint Chiefs chairman in the 1990s Powell would fight vigorously for the application of what had become a doctrine bearing his name.33

The U.S. withdrawal left Lebanon more conflict-ridden than ever. Driven out of Beirut, the PLO scattered across the Middle East, and Arafat's position was badly damaged. The Israeli government was torn by internal crisis. Peace seemed more remote than before its ill-fated invasion.

Libya and its mercurial leader, Muammar el-Qaddafi, proved yet another headache for the United States. A devout Muslim, passionately anti-colonial, the colonel had seized power in a 1969 coup that eliminated a pro-Western regime. Qaddafi entertained Nasser-like visions of leading the Arab world in triumph against the West; he had decidedly un-Nasser-like dreams of restoring Islamic fundamentalism. He closed down U.S. and British military bases, accepted Soviet aid, nationalized foreign holdings, and used oil revenues to finance terrorism and revolution. An inveterate foe of Israel, he supported Arab extremists in Syria and opposed moderates friendly to the United States in Egypt and Jordan. He also subverted his African neighbors Chad, Sudan, and Niger. By the mid-1970s, the colonel had moved to the top of America's enemies list. In 1980, Carter broke diplomatic relations.34 Because Qaddafi took special delight in tweaking the American eagle's beak, the Reagan administration became obsessed with him. Haig labeled him a "cancer that had to be cut out," Reagan a "mad dog." The administration also saw his provocations as a pretext to demonstrate that the United States would no longer be pushed around.

In 1981, it took steps to housebreak the mad dog. The navy conducted "training exercises" in the Gulf of Sidra to challenge Qaddafi's claim to a 120-mile "Zone of Death" off Libyan shores. When Libyan planes attacked U.S. jets, the Americans, to the president's delight, shot them down. Qaddafi retaliated by widening his terrorist attacks. In response to intelligence reports of Libyan death threats against Reagan and other U.S. officials, some of them of dubious reliability, the administration prepared for military retaliation. A top-secret task force searched for ways to get rid of Qaddafi without violating restrictions against assassination of foreign leaders. It ordered all Americans out of Libya. In February 1982, the United States stopped purchasing Libyan oil.

The linkage of Qaddafi with international terrorism in Reagan's second term furnished the excuse for action long on the drawing board. Terrorism traditionally has been the weapon of the weak. The use of violence to further political aims, with innocent civilians often the victims, had roots as deep as humankind. The growing frustration of Arabs and especially Palestinians after the Six-Day War brought terrorism full force to the Middle East. Its proliferation in the 1970s elevated it to the top of U.S. foreign policy concerns.35

Reagan vowed "swift and effective retribution" against terrorists but found himself handcuffed in doing anything. The administration had been embarrassed by the way terrorists had driven it from Lebanon, and seven Americans were held captive there after the withdrawal. In June 1985, a TWA flight was hijacked, and in the full glare of publicity thirty-nine Americans were held captive for seventeen days. During the Christmas holidays, terrorists exploded bombs in airports in Rome and Vienna, killing five Americans. Reagan was stunned by the December attacks. Libya was a handy target. The smoking gun came in the form of intelligence linking Qaddafi to the December 1985 bombing of a West German discotheque in which one GI was killed, fifty injured.36

Claiming "irrefutable" evidence connecting Qaddafi to recent terrorist attacks, Reagan ordered retaliation. In the spring of 1986, the navy returned to the Gulf of Sidra and attacked Libyan naval forces and shore installations. In April, the administration ordered air attacks on Tripoli itself, allegedly in retaliation for Libyan sponsorship of terrorism and against facilities used to prepare terrorist activities. The real purpose was likely to eliminate Qaddafi. In either case, the bombing failed. The United States dropped ninety two-thousand-pound bombs, destroying Libya's air force and Qaddafi's residence. Thirty civilians died and many more were injured, provoking Libyan charges of terrorism against the United States. Qaddafi's house and the tent he often slept in were hit. Family members suffered injuries; a fifteen-month-old adopted daughter was killed. The colonel himself survived, perhaps, an air force officer lamented, because he had been in the toilet.37

The bombing of Tripoli had mixed results. In the immediate aftermath, the volatile Libyan leader was conspicuous by his silence, producing U.S. boasts that the bombing had shut him up. In any event, having made its point, the administration seemed willing to accord Qaddafi the inattention he deserved. The absence of further major terrorist attacks evoked claims that Reagan had effectively dealt with a major problem, but the truth appears more complicated. More important than the bombing in dealing with terrorism were the improved internal security measures taken by the Western European nations and their expulsion of Libyan diplomats and others suspected of belonging to terrorist networks. In addition, U.S. and European sanctions forced Syria to dismantle terrorist operations that were more significant than Libya's. The apparent lull in late 1986 was deceptive. The number of incidents actually increased the next year. Moreover, the Western nations seemed only slightly better prepared to cope with terrorism than before, and their continuing vulnerability left open the possibility of new attacks at any time. When four Americans were kidnapped in 1987, Reagan publicly and ruefully conceded that there was little he could do. The December 1988 explosion of a Pan American airliner over Lockerbie, Scotland, from a terrorist bomb, later linked to Libya, underscored the stubborn persistence of a problem that vexed the administration like no other.

While attempting to tame Qaddafi with bombs, the administration also sought to open doors to Iran through the sale of arms, an ill-conceived, bumbling, and illegal ploy that damaged its credibility abroad and popularity at home.38 In September 1980, Iran and Iraq plunged into a bloody struggle of attrition that would last almost nine years and cost an estimated seven hundred thousand dead, nearly two million wounded. The United States at first supported Saddam Hussein's Iraq, but as Iran faltered in the mid-1980s some officials found reasons to approach Tehran. Reagan was obsessed with recovering the seven hostages held by pro-Iranian extremists in Lebanon, and indications that Tehran might be able to influence their fate enticed him to trade arms for their release. He reportedly told friends that he was willing to go to prison to get the hostages out.39 CIA director Casey believed that growing factionalism in Tehran might enable the United States to establish contacts among "moderates" that could be useful if the Khomeini government fell. As the USSR stepped up aid to Iraq, some Americans worried that an Iranian defeat would leave the Persian Gulf open to Soviet penetration. Others listened to Israelis who suggested that Iran might be brought around to a more moderate position. National Security Adviser Robert McFarlane, a lightweight notoriously lacking in foreign policy experience and political acumen, entertained grandiose visions of duplicating with Iran Kissinger's dramatic opening to China.40

Thus began an imbroglio that would temporarily cripple the Reagan presidency. The misadventure was made possible by Reagan's detachment, Shultz and Weinberger's inability to cooperate in stopping a venture both vigorously opposed, and the absence of a strong White House chief of staff to rein in misguided NSC zealots. Between the late summer of 1985 and the autumn of 1986, NSC operatives sold to Iran 2,004 TOW anti-tank missiles and fifty HAWK anti-aircraft missiles for assurances of assistance in securing the release of American hostages. The gambit violated the nation's announced policy of denying weapons to nations aiding terrorists and its arms embargo against Iran. U.S. officials did not inform Congress what they were doing, as the law required. They relied on Israel, which had its own interests in the matter, and on Manuchehr Ghorbanifar, a shady Iranian middleman who had failed numerous CIA lie detector tests and had been correctly called a "talented fabricator." At times the affair took on the trappings of farce, as when McFarlane and his assistant Marine Lt. Col. Oliver North, traveling under false passports, carried to Tehran a key-shaped cake and a Bible signed by Reagan as gestures of U.S. goodwill. On another occasion, North conducted a bizarre late-night tour of the White House for a member of Iran's Revolutionary Guard. The Americans overcharged the Iranians for many of the weapons and in some cases turned over old Israeli stocks, some, ironically, still bearing the Star of David. In the end, they were outmatched as bargainers, exchanging weapons for promises of the release of hostages from those they condescendingly dismissed as "rug merchants."41

What became known as "Irangate" produced, in Cannon's apt phrase, "a catastrophe" that "sometimes resembled a comic opera with tragic overtones and an unhappy ending."42 The United States secured the release of only three hostages—three others were promptly taken to replace them. Reagan had repeatedly vowed not to deal with terrorists. When a Beirut newspaper broke the story in November 1986, his credibility was shattered. His lame efforts to justify a bad deal in terms of geopolitics fell flat. He had been so successful avoiding blame for anything that went wrong that he was known as the Teflon president, the man to whom nothing stuck. Irangate changed that, at least for a time. The president appeared ignorant or incompetent—or both. His administration descended into bitter infighting as beleaguered officials tried to save their skins. A long-restless Congress was spurred to go after a once invulnerable president. When it became known that proceeds from the arms sales were used to get around congressional restrictions against aiding U.S.-backed revolutionaries in Nicaragua, the administration was for a time reduced to impotence. Another president found himself stuck to the Iranian tar baby.

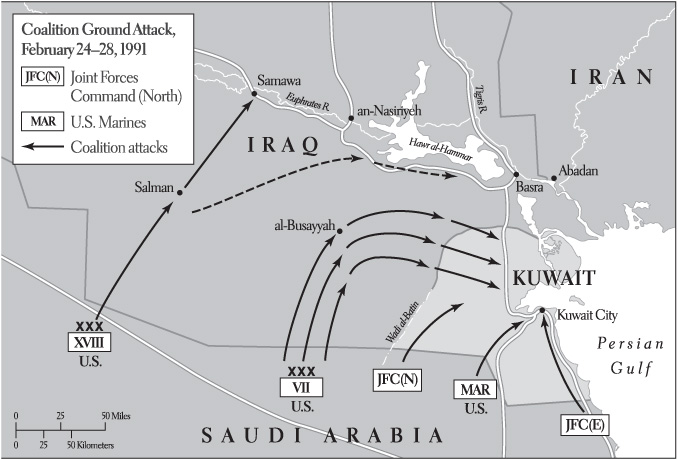

To keep oil flowing through the Persian Gulf, the administration in the summer of 1987 assembled in the Persian Gulf an armada of some thirty warships including the legendary battleship USS Missouri. The stated aims were to defend freedom of the seas and, of course, to deflect Soviet influence from a critical region. From the outset, the Persian Gulf intervention was surrounded by controversy. The Reagan administration never clearly explained why it acted. The cost was astronomical—$1 million a day. United States naval forces were bound by defensive rules of engagement and exposed to people the chief of naval operations admitted were "a little bit loony." On several occasions, the United States came close to getting sucked into the war. In May 1987, an Iraqi aircraft mistakenly attacked the USS Stark, killing thirty-seven sailors. A year later, a U.S. warship struck an Iranian mine and was disabled. The navy retaliated by putting out of action much of the tiny Iranian "fleet." In July 1988, nervous sailors aboard the USS Vincennes mistakenly shot down a civilian Iranian airliner, killing all of the 290 passengers and crew. Despite all these dangers, the convoy achieved valuable results. By helping numerous convoys steam safely through the gulf, the navy managed to sustain oil shipments from the Middle East to Western Europe and Japan. United States intervention contributed at least indirectly to the end of the Iran-Iraq war in July 1988.43

During 1988, world attention shifted back to the basics of Middle East politics. In late 1987, Palestinians in the Gaza Strip and West Bank territories occupied by Israel during the 1967 war launched a spontaneous and apparently leaderless series of sustained riots and demonstrations, including direct attacks on Israeli soldiers. Israel responded with repression, and by December 1988 more than three hundred Palestinians had been killed, seven thousand injured, and five thousand jailed in what came to be called the "uprising," or intifada (literally translated as shaking off). Initially reluctant to intrude in what was plainly an intractable and explosive problem, the Reagan administration saw no choice as the violence escalated. Revising old proposals to meet new circumstances, Shultz set forth a plan for an interim period of Palestinian "self-administration" in the occupied territories preliminary to a broader settlement between Israel and its Arab neighbors. PLO leader Yasser Arafat eventually agreed to a dialogue looking toward peace talks, but Israel continued to reject Shultz's proposals and set out to create more settlements in the occupied territories. After seven years of erratic U.S. involvement, and considerable frustration, the Middle East remained as volatile and dangerous as ever.44

In the April 1, 1985, issue of Time magazine, conservative columnist Charles Krauthammer hailed the emergence of a "Reagan Doctrine" of "overt and unashamed" aid to "freedom fighters" seeking to overthrow "nasty Communist governments."45 Although it was given a name only in the second term, and then by a journalist, what came to be called the Reagan Doctrine was established policy from the start.46 The administration's major innovation in foreign affairs, it marked a sharp departure from the dominant trends of Cold War foreign policy. John Foster Dulles had talked of rolling back Communist gains in Eastern Europe. The United States at times had attempted to destabilize and even overthrow leftist governments. But in general, containment had meant acquiescence in Communist governments already in power. The Reagan Doctrine was rooted in long-standing right-wing disdain for containment. It was pushed by conservative members of Congress and administration hardliners, especially CIA director Casey, as a way to exploit Soviet overextension, roll back recent gains, counter the noxious Brezhnev Doctrine, by which the Kremlin had claimed the duty to intervene anywhere socialism was threatened, and even undermine the USSR itself. Reagan enthusiasts claim great success for the doctrine, especially in Afghanistan, where they assign it a major role in America's Cold War victory.47 In truth, the vigor of its implementation never matched the heat of its rhetoric. Even in Afghanistan, where it enjoyed some tactical success, its strategic impact has been overstated.

Although it is not generally included under the Reagan Doctrine, a non-military covert program in Poland stands as a modest success story. In Eastern Europe, generally, the CIA after 1982 had encouraged and helped finance protests, demonstrations, newspaper and magazine articles, and television and radio shows highlighting the evils of Soviet domination. Carter had initiated covert action in Poland. In June 1982, Reagan gained Pope John Paul II's blessings for an expanded program for the pontiff's native country. Casey and others considered Poland the weakest link in the Soviet bloc. The United States helped the non-Communist opposition group Solidarity stay in contact with the West and promote its cause inside Poland. United States funds purchased personal computers and fax machines and assisted Solidarity members in using them to publish newsletters and propaganda. The covert program helped keep Solidarity alive during the years of martial law and prepared it to seize power when the regime collapsed.48

Elsewhere, the Reagan Doctrine was applied unevenly and with mixed results. As part of its broader strategy of opposing Soviet expansionism and that of its clients, the administration furnished limited, covert aid to a disparate and unwieldy coalition of insurgents opposing the Vietnamese-imposed puppet government of Cambodia. No U.S. officials were eager for reintervention in former French Indochina. They also worried that aid might fall into the hands of the despicable Khmer Rouge, the most potent of the rebel factions. Assistance therefore remained very small, was distributed through the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and had no more than a marginal effect on the diplomatic settlement that led to eventual Vietnamese withdrawal.49

In southern Africa, race and the Cold War defined U.S. policies. Reagan and his top advisers had little sympathy for black nationalism, linking the African National Congress with Communism. Rather than challenge apartheid, they claimed to follow a policy of "constructive engagement," but they said nothing when the South African government brutally cracked down on dissidents. Under the inspirational leadership of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, black protest in South Africa won rising international sympathy during the 1980s, along with growing demands for sanctions against the Pretoria government. In the United States, the drive for sanctions came mainly from private-sector pressure groups, with vocal support from college campuses. Responding to moral issues and political exigencies, Congress in 1986 passed over Reagan's veto a bill imposing broad sanctions. Shultz admitted that the domestic costs of leaving the South African government to its own devices far exceeded the benefits.50

The Reagan Doctrine was employed in southern Africa in a cautious and entirely practical manner. State Department pragmatists fended off heavy pressures from congressional conservatives and administration hardliners to assist a brutal right-wing rebel group in Mozambique. Indeed, ironically, as part of its regional strategy, the United States furnished limited aid to a leftist government.51 In Angola, U.S. aid was employed to support a broader diplomatic effort to get Cuba and South Africa out, end the civil war, and secure independence for Namibia. The administration in 1985 initiated covert assistance through Zaire to UNITA's Jonas Savimbi, the darling of the American right. But as administered by the State Department, the assistance was used not to defeat the Soviet and Cuban-backed MPLA but through what Shultz called "stealth diplomacy" to encourage a diplomatic settlement. By helping achieve a military stalemate after Cuban and South African escalation, U.S. aid may have contributed to the withdrawal of outside powers and the beginning of negotiations. Continued assistance to Savimbi actually delayed an end to the Angolan civil war.52

The Reagan Doctrine enjoyed major success in Afghanistan, the largest covert operation to that time, but even here the administration's noisy rhetoric belied its generally cautious actions. The role of U.S. aid was less decisive than the Reaganites have claimed. Carter had initiated limited, covert assistance to the Afghan and foreign mujahideen fighting the Soviet invaders. From the outset, Casey pushed to "bleed" the Soviets in Afghanistan, but the administration moved slowly for fear that direct U.S. involvement might provoke Moscow to escalate the Afghan war or even attack Pakistan. Responding to mounting pressure from Congress and public lobbying groups, the administration increased aid to the Afghan "freedom fighters" in 1983 and 1984. But it was only in March 1985, in response to a threat of Soviet escalation, that Reagan ordered his advisers to do "what's necessary to win."53 Aid jumped from $122 million in 1984 to $630 million in 1987. Working through Pakistani intelligence, the CIA provided rebel forces intelligence gathered from satellites and other sources, established training camps for Afghan fighters, and even helped plan some operations. In what is generally considered the decisive move, the administration in early 1986 provided the Afghans with lethal handheld Stinger anti-aircraft missiles. The Stingers at first exacted a devastating toll on Soviet helicopters and have been labeled the "silver bullet" that drove the USSR from Afghanistan.54

The allegedly decisive significance of the Stingers has swelled into one of the great myths of the Cold War. After heavy early losses, the Soviets developed countermeasures to neutralize the missiles. In any event, the new Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, largely out of a need for U.S. trade and technology, had decided to withdraw from Afghanistan even before the first Stingers arrived.55 Like most military victories, moreover, the Reagan Doctrine's success in Afghanistan bore hidden costs in the form of what the CIA calls "blowback." The need for Pakistan's support in Afghanistan led the United States to turn a blind eye toward its nuclear program. The cultivation of heroin financed much of the war in Afghanistan, undermining the simultaneous U.S. "war" on drugs. As the CIA had feared, large numbers of Stingers ended up on the shelves of the international arms bazaar. Some were purchased back at grossly inflated cost. United States aid also helped ensure the eventual triumph of the fundamentalist Taliban regime in Afghanistan. The Islamic fighters the United States helped train would in time turn on their benefactors, launching deadly attacks against U.S. assets abroad and even the American homeland itself.56

The major Third World battleground was closer to home. Echoing John Kennedy twenty years earlier, ambassador to the United Nations Jeanne Kirkpatrick called Central America and the Caribbean the "most important place in the world for us." Reagan and Casey believed that the defeat of Communism in one area might cause the Soviet empire to crumble.57 Determined to roll back perceived Communist gains in its own backyard, the United States employed the Reagan Doctrine in Nicaragua and used old-fashioned gunboat diplomacy in Grenada in an effort to topple leftist governments. In El Salvador, it used conventional Cold War methods to bolster a right-wing government against leftist insurgents. Although it refrained from large-scale military intervention except in Grenada, the administration invested great energy and resources in the region. Central America became the political and emotional cause célèbre of the 1980s, a source of unrelenting and bitter dispute between conservatives and liberals over the nation's proper role in the world. The Reagan administration achieved none of its main goals, but its intervention had a huge impact on the region.58

By the time Reagan took office, U.S. dominance of a traditional sphere of influence was being challenged from without and within. America's traditional economic hegemony was threatened by competition from Japan

and Western Europe. Since the 1920s, the United States had relied on friendly military dictators such as Trujillo and Somoza to maintain order and protect its interests, but a half century later they too had come under fire. The worldwide economic crisis of the 1970s brought poverty and misery to the region and provoked mounting popular unrest. The Catholic Church had long been a bulwark of the established order, but in the 1970s, following principles set forth by Pope John XXIII, radical priests developed a liberation theology that encouraged the masses to assert themselves for democratic change.59 Carter's human rights policy highlighted the abuses perpetrated by military governments; by cutting off military aid, it undermined their legitimacy and hence their authority. Before Carter left office, a coalition of revolutionaries had toppled the despised Anastasio Somoza in Nicaragua. As Reagan entered the White House, another threatened the government of El Salvador.

The administration's Central American policies developed from a jumble of conflicting ideas and forces. Cuba and the Soviet Union naturally expressed sympathy for the revolutions in Nicaragua and El Salvador and provided limited assistance. Although they professed commitment to a pluralist democracy and a mixed economy, the Sandinistas—befitting their name—often took vocal anti-U.S. positions. "We have to be against the United States in order to reaffirm ourselves as a nation," one leader asserted.60 Not surprisingly, therefore, Reagan and most of his top advisers expressed grave concern about a new "Soviet beachhead" in the hemisphere, "another Cuba." The president was also much taken with neo-conservative Kirkpatrick's 1980 article that attacked Carter's human rights policies for undermining friendly authoritarian governments that could evolve into democracies while indirectly encouraging totalitarian governments that would never change.61 Many U.S. officials saw Central America as a place where the United States could reestablish its credibility in the aftermath of Vietnam.

There were also powerful constraints against intervention. Especially in its first months, the White House staff was determined not to let foreign policy interfere with passage of the president's economic program. Reagan himself was wary of intervention. His military advisers, still rebuilding the forces crippled by one disastrous Third World entanglement, were not disposed toward another. Polls made quite clear the public's lack of enthusiasm for sending U.S. troops to Central America. The mention of such a possibility was guaranteed to unloose a free-for-all in Congress.62 Thus, while attaching rhetorical importance to the struggles in the Caribbean and Central America, the administration, except in Grenada, acted with some restraint. Even more than in the Middle East, moreover, Reagan's Central American policies reflected his administration's undisciplined managerial style.

Secretary of State Haig pushed Central America to the top of the foreign policy agenda before the Reaganites had settled into their offices. Viewing the region strictly in East-West terms, the hyper-energetic and volatile former Kissinger aide fired the department's Central American experts in the biggest purge since John Foster Dulles, replacing them with old Vietnam hands—the gang who couldn't shoot straight, they came to be called. He informed Reagan that tiny, impoverished El Salvador was "one you can win." Certain he had been given complete control over foreign policy, he pushed for going to the source of the problem: Cuba. "You just give me the word," he bragged to the president in early 1981, "and I'll turn that fucking island into a parking lot." In February, the department released a white paper purporting to contain "definitive evidence" that Nicaragua, Cuba, and the Soviet Union were making El Salvador a key Cold War battleground.63

Although it stopped well short of Haig's recommendations, the administration made a substantial commitment in El Salvador. Haig's Cuban venture "scared the shit" out of even the hard-core anti-Communists around Reagan. His out-of-control, nationally televised statement that he was in control after a March 1981 assassination attempt on the president sealed his fate in the cabinet. The White House was also determined not to let Central America get in the way of the president's domestic program.64 Still, the administration refused to leave El Salvador to its own devices. To support its regional anti-Communist offensive, it launched a major military buildup in neighboring Honduras and conducted much-publicized maneuvers in Central America. It increased military aid to El Salvador to $25 million and the number of U.S. military advisers to fifty-four. The goal shifted from ending the bloodshed and arranging a political settlement to defeating the insurgency, thus giving encouragement to the Salvadorean right, especially the notorious death squads who targeted even church leaders. Even these limited measures stirred memories of Vietnam, arousing sufficient protest in Congress and the country to underscore the difficulties of implementing a truly aggressive policy in Central America.65

Haig's "one you can win" brought much frustration for the United States and more misery for El Salvador. Throughout the first term, the administration engaged in a running battle with Congress over El Salvador, all the while implementing its policies, in former senator Sam Ervin's words, on the "windy side of the law."66 The White House employed various subterfuges to adhere to its self-imposed limit of fifty-four advisers and increase military aid without congressional approval. Military assistance grew to more than $196 million in 1984. Massive economic aid helped cover the deficit caused by the government's military spending. Even with enormous U.S. support, the Salvadorean military could gain no more than a bloody stalemate. To appease Congress, the administration pushed for elections in El Salvador. In time, a crude, hybrid form of democracy emerged there. The United States pinned its hopes on centrist José Napoleon Duarte, but the well-intentioned leader could neither control his military nor curb right-wing human rights abuses. He had little success implementing domestic reforms. Indeed, the austerity program Washington pushed on him in the mid-1980s imposed additional hardships on already impoverished people. The White House managed to get El Salvador off the front pages in the second term and could claim it had denied the insurgents victory. Without approval from the United States or his own military, however, Duarte could not end the war by negotiating with the insurgents. El Salvador remained wracked by violence, its economy in shambles.67

The administration's high-tech version of old-fashioned gunboat diplomacy in tiny Grenada in the fall of 1983 was more successful. With Cuban aid, the Marxist government of Maurice Bishop had built a twelve-thousand-foot jet runway on the 133-square-mile eastern Caribbean island and granted the Soviets permission to use it. Already nervous about a Cuba-Grenada-Nicaragua axis in the hemisphere, jittery U.S. officials were further alarmed in mid-October when extremists in the ruling party placed the government under house arrest and executed Bishop. Although Cuba had backed Bishop against those who killed him, an administration already obsessed with Grenada feared yet another "Soviet beachhead" in the Caribbean. Haunted by memories of Iran in 1979, the president worried that the eight hundred American medical students on the island might be taken hostage. Grenada also provided a much sought-after opportunity following the Lebanon debacle to burnish U.S. military credibility. Thus on October 25, Reagan dispatched a seven-thousand-man force to rescue the American students and "restore democracy" on Grenada.68

America's "lovely little war" (a phrase coined by a journalist) in Grenada did not come easily.69 The United States lacked adequate intelligence, even accurate maps, for what was dubbed Operation Urgent Fury. Each of the military services insisted on a role. Coordination was poor at best, and the operation went off with anything but surgical precision. The landing force met stiff resistance from a small force of Cubans armed with obsolete weapons. Nine U.S. helicopters were lost; twenty-nine U.S. servicemen were killed, many from friendly fire and accidents, and more than one hundred wounded. The clumsy manner in which the mission was executed for a time left the students in harm's way. Ultimately, the operation succeeded because it had to.70 The vastly superior invading force rescued the students and took control of the island. Whatever the military flaws, Grenada was a huge political success. Reagan skillfully exploited the intervention to erase memories of Beirut. The administration exulted in what the president later called a "textbook success," reveled in this first rollback of Communism, and proclaimed that Grenada would send a clear message to Moscow, Havana, and especially Managua.71

Indeed, by the time of the Grenada operation, Nicaragua had become the focus of U.S. concern in Central America, a major test case for the Reagan Doctrine. In December 1981, at Casey's urging, Reagan authorized $20 million for a covert operation to organize and train in Honduras a five-hundred-man army of Nicaraguan "contras" (for counterrevolutionary). The stated purpose was to interdict Sandinista assistance for the Salvadoran insurgents, but top U.S. officials had more ambitious motives. The State Department hoped that a military threat might encourage the Sandinistas to negotiate, about what it was not entirely clear. Casey and the hawks wanted to "make the [Sandinista] bastards sweat."72 For the president and many of his top advisers, the real aim was to overthrow the Sandinista government.

The not-so-covert war against Nicaragua grew steadily from 1981 to 1984. Reagan in time adopted the contras as his own, publicly referring to them as "our brothers" and the "moral equal of our Founding Fathers." He came to see Nicaragua as the major front in a global struggle "to repeal the infamous Brezhnev Doctrine, which contends that once a country has fallen into Communist darkness, it can never be allowed to see the light of freedom." The operation began with a small group of former officers from Somoza's National Guard. Supposedly limited to five hundred men, the contra force grew into a guerrilla army of ten thousand. Despite the increase in size, the contras never really threatened the government. They gained notoriety for repeated human rights abuses against peasants. The CIA took over operational control in late 1982. Agency operatives backed the contras' efforts the next year by attacking Nicaragua's fuel storage and mining its harbors. To intimidate Nicaragua, the United States in the summer and fall of 1983 conducted military operations in Honduras lasting six months and involving more than four thousand troops.73

Even more than El Salvador, the widening war against Nicaragua provoked increasingly bitter debate in the country and Congress. Not persuaded of the urgency of the alleged Sandinista threat or the viability or legitimacy of the contras, and above all fearful of another Vietnam, Americans strongly opposed deepening involvement in Nicaragua. As early as October 1982, an already wary Congress forbade the use of U.S. funds to overthrow the Sandinista government, a restriction the administration readily dismissed by continuing to insist—disingenuously—that was not its intention. A more serious threat developed in 1984. Press reports of the CIA mining of Nicaraguan ports set off a furor and opened a sizeable credibility gap between the executive and Congress. A veteran of the glory days of the OSS in World War II, Casey had contempt for "those assholes on the Hill" and especially for congressional oversight of covert operations. From the outset, he had ignored, misled, or deceived legislators about Nicaragua. He mumbled almost unintelligibly—his voice had a "built-in scrambler," according to Weinberger—and when all else failed he gave answers no one could understand.74 The realization after the mining operations that they had been repeatedly deceived on Nicaragua emboldened congressional foes of contra aid and infuriated even supportive legislators like Arizona senator Barry Goldwater. With a presidential election approaching, the administration in the summer of 1984 managed to get Nicaragua off the front pages by going through the motions of negotiating with the Sandinistas. But after months of often fractious debate, Congress in October passed another measure effectively cutting off funding for the contras. Reagan responded by instructing his subordinates to "do whatever you have to do to help these people keep body and soul together."75

The cutoff in aid and Reagan's open-ended instructions tested the ingenuity of NSC staffer Oliver North, a zealous marine labeled by one senator the only "five-star lieutenant colonel in the history of the military." Tireless, charming, not troubled by scruples about the truth or the law, North in the words of a colleague could "speak a blue haze of bull shit."76 Utterly devoted to the president, he and his cohorts observed no bounds in carrying out what they thought were his wishes. Contemptuous of the institutions of government—their code name for the State Department was Wimp—North and his "cowboys," presumably with Casey's blessings, arranged an incredibly complex operation to implement policies outside the bureaucracy and away from the scrutiny of Congress. In effect, they privatized U.S. foreign policy. With Reagan's knowledge and encouragement, NSC staffers solicited a total of $50 million from friendly governments such as Taiwan, Brunei, and Saudi Arabia, which alone contributed $32 million, and from right-wing U.S. citizens such as beer magnate Joseph Coors. In an early 1986 venture that North called a "neat idea" and Casey "the ultimate covert operation"—and that ultimately proved their undoing—they diverted to the contras funds from arms sold to Iran.77 North used Project Democracy, an ostensibly private corporation established by Reagan to "cultivate the fragile flower of democracy" across the world, as the instrument of his operation. The "Enterprise," run by retired Air Force Gen. Richard Secord, had its own ships and airplanes and private landing strips throughout Central America, dummy corporations and secret banking accounts, and special highly sophisticated coding devices provided by North from the super-secret National Security Agency. Some of the operatives appear to have reaped handsome profits, and millions of dollars could not be accounted for. A $10 million contribution from the sultan of Brunei was mistakenly deposited in the account of a Geneva businessman.78

The administration's clumsy efforts to cover up its sins got it into more hot water. When the story of arms sales to Iran broke in November 1986, the Justice Department dawdled its investigation of NSC wrongdoing while North and his glamorous, equally zealous secretary, Fawn Hall, shredded thousands of "problem memos." National Security Adviser John Poindexter deleted five thousand e-mails (later retrieved). McFarlane doctored a "chronology" to obscure the president's role. Reagan at first alternated between denying knowledge of what had happened and blaming lapses of memory. "There was an awful lot going on and it's awfully easy to be a little short of memory," he confessed on one occasion. Testimony before a congressional committee investigating what came to be known as the Iran-Contra Affair subsequently revealed that he knew a great deal and had approved much. In time, he publicly boasted that funding the contras was "my idea to begin with."79 The scandal at least temporarily crippled the Reagan presidency. The president's approval rating plummeted to 36 percent; in the fall elections, the Republicans lost control of the Senate. The Great Communicator escaped impeachment mainly because it could not be established that he had ordered the illegal actions.

The war in Nicaragua ended through a bizarre, almost surreal, chain of events—despite rather than because of the United States. The architect of a cease-fire was Costa Rican president Oscar Arias Sánchez. Educated in the United States and Britain, a staunch anti-Communist who disliked the Sandinistas almost as much as the Reaganites, Arias feared that the contra war might escalate into a regional conflict. Small of stature, by reputation an intellectual, he proved a tough and creative diplomat. He devised a peace plan calling for a cease-fire, an end to outside aid, and democratization for Nicaragua. He locked the presidents of El Salvador and Honduras in a room until they went along, a trick he claimed to have learned from Franklin Roosevelt. He courageously stood up against bullying and threats from the United States; once when Reagan summoned him to the White House for a fifteen-minute lecture, Arias responded with a statement twice as long emphasizing that on Nicaragua the United States stood alone. In a strange gambit that backfired, the administration enlisted Democratic House of Representatives Speaker Jim Wright to draft a peace plan. When Wright backed Arias's proposals, an administration weakened by the Iran-Contra revelations had little choice but to go along. Defiant to the end, Reagan and his advisers counted on the Sandinistas to reject the plan and continued to seek to undermine it by securing additional contra aid. To Washington's shock, the Sandinistas went along because of Nicaragua's dire economic straits and in full expectation that they would win elections set for 1990. When Congress again rejected aid for the Nicaraguan rebels, the contras had no choice but to accept Arias's proposals. Despite persistent U.S. efforts at sabotage, a cease-fire was approved in March 1988. Although it did not bring peace, it did make war more difficult to wage.80

Once the most secure outpost of the U.S. empire, Central America during the Reagan years provided the most graphic example of the limits of U.S. power. Thinking it could win one in its own backyard, the United States set out in El Salvador and Nicaragua to exorcize the ghosts of Vietnam. The Reagan administration could claim victory in the narrow sense that the insurgents never gained power in El Salvador. Moreover, to the shock of everyone, the Sandinistas lost the 1990 election to a centrist coalition and willingly gave up power. In fact, the Reagan Doctrine ran aground in Central America. Despite millions of U.S. dollars, the insurgency dragged on in El Salvador, and the extreme right emerged victorious in March 1988 elections. Honduras was increasingly militarized and destabilized politically. Without the intervention of Arias and Wright, the elections that deposed the Sandinistas would never have taken place. The Reagan administration grossly exaggerated the Communist threat in Central America. It poured more than $5 billion into what became a "sterile regional bloodletting." At home, its misguided and often illegal policies polarized the political atmosphere and corrupted the political process. Abroad, it defied international institutions such as the UN and the World Court. Rarely in the history of U.S. foreign policy had so much zeal, energy, and money been invested in such a dubious and destructive cause. At the end, the White House's determination to back the contras "body and soul," in Reagan's words, seemed about little more than pride and stubborn commitment.81

The result for Central America was catastrophic, an estimated thirty thousand dead in Nicaragua (proportionately equal to the total U.S. killed in the Civil War, both World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam) and eighty thousand in El Salvador, many of them civilians. The United States "laid waste to Nicaragua," leaving an economy with 1,300 percent inflation and rampant unemployment.82 The administration claimed some responsibility for the growth of democracy in Latin America as a whole, and during the 1980s seven civilian governments did come to power. But hemispheric leaders protested the "Centralamericanization" of U.S. policy and warned that a crisis caused by $420 billion of debt imperiled the fragile democratic gains and raised the threat of a new wave of extremism from left and right.83

Had Reagan left office in 1987, his presidency would have gone down a failure, the victim of his own inattention and mismanagement so starkly manifested in Iran-Contra. In fact, even while he was reeling from setbacks in the Middle East and Central America, he was engaged in a dramatic and totally unexpected turnaround in relations with the Soviet Union. These initiatives would help bring about the annus mirabilis of 1989 when peace and freedom seemed to break out everywhere and a diplomatic revolution comparable to that of World War II began to take shape. In a little more than a year, Reagan rose from the ashes of scandal to heroic stature, the "man who ended the Cold War," in the exuberant words of one of his advisers.84 A triumphalist myth took root among Reagan partisans that by standing forth boldly for freedom, confronting the Soviets across the world, and launching a military buildup they could not match, the former actor brought the "evil empire" to its knees.