I got very excited by composer Ned Rorem’s Paris Diary and New York Diary, written by a young man on the make, obsessed with art, sex, and alcohol. Big identification. I found an LP called Songs of Love and the Rain by Rorem with a beautifully sad piano piece that I play over and over. I knew he lived on Seventieth Street, so I walked up and down his block off Central Park one night listening for the sound of a piano. Didn’t work.

Poet Tim Dlugos came over one afternoon, loved my small oil portrait of Rorem, and said, “I know Ned! Let me give him a call and see if we can go over there.” We did. Ned ushered us in, still very handsome, with a blue scarf wrapped around his neck. He had a cold. He introduced us to his cat, Wallace. Served us tea and cookies. Gossiped with Tim about New York School poets they know in common. Tim funny and laughing, Ned not so much, talking out of the side of his mouth with a pronounced lisp. He was lamenting the loss of his youth and beauty, which he has been lamenting since he was young and beautiful. That’s his thing. A self-fulfilling prophecy. I asked him something about his old friend Paul Bowles, and Ned quoted himself (I had heard him on The Dick Cavett Show tell the same anecdote last week). I admired his art collection, Joe Brainards, Jane Freilichers, Cocteau, etc. Ned seemed to eye me with suspicion, and Tim told me to get out my portrait, which I did, and propped it up on the carpet in front of the TV. Silence. Wallace came over and sniffed it, then wandered off.

“I don’t think Wallace likes it,” Ned said without smiling. He continued. “I know the photo you used for your painting. Henri Cartier-Bresson. That’s when I dyed my hair blond, of course. My suit was brown, not blue, and my tie was red, not green.”

“Uh, yeah, well, I only had that black-and-white photo,” I replied shyly. That seemed to be about it, so I put the painting back in its brown paper bag, we thanked Ned for the visit, and filed out.

Tim was embarrassed and said, “Sorry about that…I thought he’d be a little more enthusiastic. Maybe it was because of his cold.”

“That’s okay Tim, I guess he just didn’t like it.” I hope when I’m in my late fifties, some young kid brings over a portrait of me that he’s done. And, I must add, it’s a fucking good painting. Not that all my paintings are, but this one is.

Terry’s touchiness is always on alert. Sometimes I’m damned if I do and damned if I don’t. I can sense a fracture in her life. She says I’m trying to control her by offering her advice. When she has an attack of the crazies, she can get quite violent. Once I was standing in the doorway of her office, and she was screaming at me for some imagined infidelity, some groundless fears, the energy was escalating, and suddenly she launched her heavy electric typewriter at me. I did a quick two-step, and it crashed where my feet had been. There would have been some broken bones had I not Nijinskied out of the way. Once she told me that I was never going to get out of this love affair alive. It seemed to be more than an idle threat. It’s coming up on three years now. There’s been quite a bit of deterioration since the relative innocence of the first flowering of romance. Emotional fatigue. Now it’s flowers of evil, to borrow a phrase from old Charlie Baudelaire.

The Times Square Show, June 24, 1980. 201 West Forty-first Street

A group show organized by Colab, who have taken the bull by the horns. They got the use of an empty massage parlor off Times Square. I have five paintings in it (in spite of not fitting in with the show’s agenda), portraits of Ned Rorem, Colin Wilson, Wyndham Lewis (which Glenn O’Brien bought for $300), and two nudes, one of Italian starlet Leonora Fani and the other of Jane Birkin. Hung near a couple of Walter Robinson’s pulp paintings. Most of the other work has a rough political edge, do-it-yourself antifascist art done with cheap materials. Rats, hypodermic needles, barrio boys, hookers, this is the general tone. The Village Voice put artist John Ahearn on their cover, with some headline about the new presence of young voices who demand to be heard. These scruffy ghetto dwellers are barging into the art world, it said in effect. It worked on the dealers. Jimmy’s boyfriend Stefanotti asked me to have a show in a few months’ time. (Me being the lesser of evils contained in the Times Square Show. My pictures would not seem to have an axe to grind with art history. I am the safe choice.) The Times Square Show is a chance for all of us to see what everyone else is doing, since none of us have representation and we work in a vacuum. We only see each other at scuzzy nightclubs. On record covers, in underground magazines, on flyers.

Life magazine runs a picture of Amos Poe in bed under a poster for Unmade Beds (with image of me taking a photograph). It’s an article on the “new new wave.” Amos “takes his characters and icons from vintage B-movies—cops and call girls, gangsters and hit men—and weds them to themes of alienation and violence. New wave performers play the parts, and the new music serves as its soundtrack,” says the article. The underground is slowly surfacing overground.

The Reader

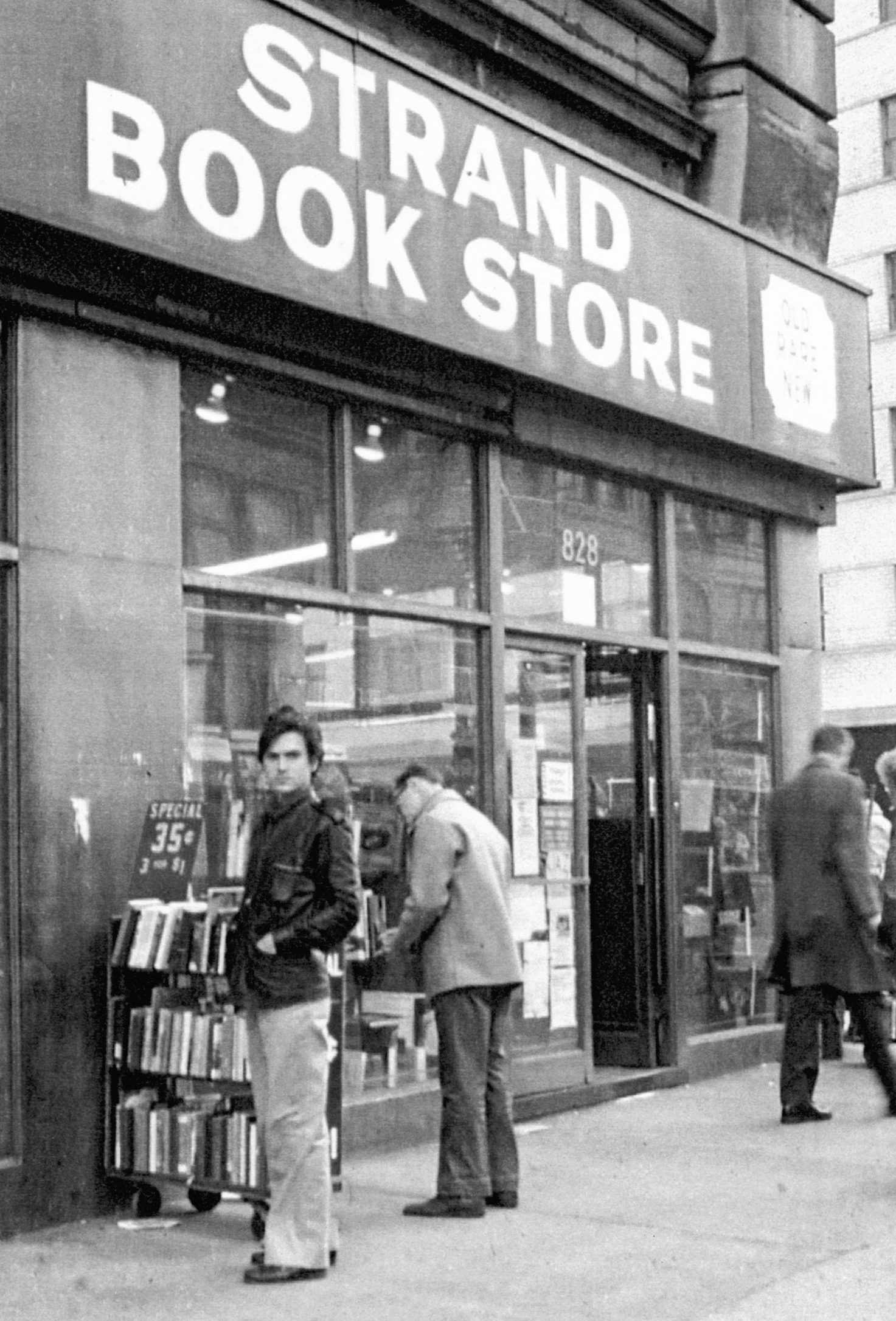

Books

Bright Orange for the Shroud, John D. MacDonald

Laughter in the Dark, Vladimir Nabokov

November, Georges Simenon

Self-Portrait, Man Ray

Blue Movie, Andy Warhol

The Paper Snake, Ray Johnson

Helen and Desire, Alexander Trocchi

The Carnal Days of Helen Seferis, Alexander Trocchi

White Thighs, Alexander Trocchi

The Woman of Rome, Alberto Moravia

Lunch Poems, Frank O’Hara

The Basketball Diaries, Jim Carroll

The Love Object, Edna O’Brien

Life with Picasso, Françoise Gilot

Brideshead Revisited, Evelyn Waugh

Dispatches, Michael Herr

Echoes of Celandine, Derek Marlowe

I Want It Now, Kingsley Amis

That Uncertain Feeling, Kingsley Amis

First Love, Last Rites, Ian McEwan

The Cement Garden, Ian McEwan

Miss Silver’s Past, Josef Skvorecky

Delmore Schwartz, James Atlas

The French Lieutenant’s Woman, John Fowles

A Waiting Game, Michael Powell

Heaven and Other Poems, Jack Kerouac

October 7

Reception at the Mudd Club for a serigraph I did of Harry Crosby, called Lullabye, edition of fifty. BOMB magazine ran a study for it, full page.

One day, while I was on a bender, I was proofing the silk screen with the printer, and afterwards found myself standing on the corner of Sixth Avenue and Fourteenth Street. Who should appear but beautiful Annette, the dreamy girl who screwed me and DuPrey on the same sultry night. Long time, no see. “Are you drunk?” she asked. I nodded. “Good,” she said, and took me to her nearby apartment after picking up a bottle of champagne. We went straight to bed, and feasted on each other like starving carnivores. “You’ve become more sexual over the past five years,” she said, smiling. “I thought you were ethereal before.” She took me to One Fifth for dinner, and wrote on the inside flap of a matchbook, “I love you and NY” with her eyebrow pencil. Passed it across the table to me. It was a memorable, spontaneous, romantic interlude, the kind Greenwich Village is/was famous for. It was the only time I actually cheated on Terry. I followed the old adage: “If you’re gonna do the time, you may as well do the crime.”

We went to see Siouxsie and the Banshees at the Academy of Music. New album is Kaleidoscope. Afterwards we went to Gordon Stevenson’s loft for a small after-party. Gordon’s in an unlistenable band with Lydia Lunch called Teenage Jesus and the Jerks. Gordon’s wife, Mireille, was killed in a car accident. They’d made a film together called Ecstatic Stigmatic, a gnarly mash-up of Catholicism and S&M. Like Gordon’s loft, which is heavy on the crucifixions and bondage apparatus. Terry’s talking with Siouxsie’s drummer and boyfriend, Budgie, a good-looking bottle blond. I attempt to talk with Siouxsie, a chilly and formidable singer wearing a lot of makeup. I like her, but she’s hard work. It is very late, and I am on the wagon and want to go home. Terry says under her breath that Siouxsie and Budgie have invited us back to their midtown hotel.

“It’s three in the morning,” I say. “Why would we go there at this time of night?”

She raises an eyebrow. “Want to?”

Oh, I see now. Bit of swinging with the Banshees. I cannot imagine getting cozy with Siouxsie, and I don’t particularly relish the thought of watching Terry getting boned by Budgie. “I don’t think so, Terry,” I said. She shot me a look that said volumes about what a repressed square I was. Tried to talk me into it. “Sorry, there’s nothing about this that appeals to me.” She goes over to the English rock-star couple to decline the offer, feeling very uncool. Sulks all the way home. It seems she’s outgrown this romance. She makes me feel like an anchor chained to her ankle.

I’m trying to pull out of my personal nosedive, while she wants to fearlessly embrace her dark side, overcome her Catholic hangups. I don’t have any religious repression to rebel against, don’t know much about Jesus, never much cared. What’s all the fuss about? Original sin? I don’t understand. So this is where we come apart. Apparently the rules have been changed.

October 17. Sam Green works for John and Yoko. He asks if I can do a mock-up logo for Lenono Records, a Rising Sun morphed with a Union Jack. Overnight. I do. I get a check in the mail for $75 signed by Yoko.

I also did some jobs for High Times and Mademoiselle. Did a cover for Dennis Cooper’s anthology called Coming Attractions.

Halloween, 1980

I finally figured out that Terry was having an affair with shitty Gordon. For six weeks! I feel a fool. Betrayed, insulted, lied to. And now that I know, she’s furious at me. Her guilt turns to anger. I talk to her calmly, she gets hysterical. She doesn’t listen, only lashes out. She wants to be “bad.” She’s vain, conceited, selfish, hypocritical. She’s finally turned into the dominatrix she was pretending to be a few nights a week. Full time now. She says she’s got “guts” to indulge in any urge she may have.

Says Gordon was cuckolded by the deceased Mireille, so now he’s getting his own back. Gordon is a bisexual creep. He tried to kiss me, too. He looks like a reptile, sharp widow’s peak, the pallor of a chronic masturbator. Slave bracelets. Motorcycle boots. Tattooed. Beady-eyed. My rival. Yuck. He’s led Terry along, preying on her insecurities and schizophrenia.

November 8, 1980

In response to my being cuckolded, I embarked on a long, joyless, drawn-out bender, as if demonstrating that if anyone was going to hurt me, it would be me doing the hurting. I’m perfectly capable of hurting myself, thank you very much! Tim Dlugos dropped by and found me in a semi-comatose state. He was horrified at the condition I was in, no food, just vodka, so made a call, and made me promise to go to an address in the neighborhood the following noon. I did, and I found to my surprise that I liked what I heard, so I continued to go every day to learn about this disease that has been calling the shots in my life. I felt hope. They said I didn’t have to drink. A novel idea, of course I have to drink, it’s what I do. Not today you don’t, they said, tomorrow’s another day. It’s only a day at a time. You don’t have to quit for the rest of your life. I told someone there I was wary of getting brainwashed. He said, “Well, no offense, but your brain could use a bit of washing.”

Sadly, I still live with Terry. If she would just move in with her rotten Don Juan it would be a lot easier. She tries to provoke me, taunts me, tests me. Doesn’t like my new sobriety. She can’t take my disapproval. Tough shit. I don’t have all the answers, I’m tired of who’s right and who’s wrong, I’m just a twenty-eight-year-old alcoholic painter. I want no more scenes.

There was a doozy of a scene. She came home one afternoon, after a night with her bit of rough trade, Gordon. They’re reading Nietzsche together. She told me they want to kill a homeless person and roll him into the Hudson, so they can tick that sin off the list. I told her she was crazy. She told me I was a conservative, repressed bore. “Just because I draw the line at murder?” I said. “Okay, then, if that makes me square, I guess I am.”

This ignited her fury. She followed me into the kitchen, my back was to her, but a second sight made me suddenly duck. She had hurled a full glass jar of Hellman’s mayonnaise at my head, which exploded on the wall in front of me with such violence that the pieces were propelled into every corner of the apartment, not just the kitchen. It sounded like a grenade going off. It would have stove in my skull. I turned, my adrenaline giving me immediate superhuman strength. I walked over to her, lifted her up by the neck with one hand, as if she weighed a pound. Her feet were dangling in the air. I looked at this fucked-up bitch and realized if she could just cease to exist, all my problems would be gone. It was a powerful impulse, one that I’ve never had before, and hope to never have again. I said, “Okay, that’s it, you’ve pushed me as far as I can go, but you can’t push me anymore. That’s it, you’re done. Now I want you to get out of here, because it’s not safe for you here, not now. So get…the fuck…out!” And then I saw something in her, in her terror-stricken face, that made me sick…a wave of admiration passed over her, even desire. I squeezed her neck one last time, and set her down. She left. I was still pulsing with a murderous energy like I’d never ever felt. I went to the bathroom mirror to see who I had become. I hardly recognized myself. I looked completely feral. Like the Wolf Man, my teeth bared, my nostrils extended, my eyes ablaze.

I’ve come to see that it’s a blessing that Gordon stole Terry away. In fact it’s the best thing that could’ve happened. How would I have ever gotten out of that toxic relationship otherwise? Maybe I thought it’s what I deserved, water finding its own level, etc. Alcoholism does a real number on your self-esteem. We didn’t have to be together; in fact, it was a terrible idea. I’m free, white, and twenty-eight. I’ve got a rosy future ahead of me.

It’s so nice to wake up without a hangover. My imagination roams freely. I experience nuances I never knew. Attentive to little sensations. I have been my own worst enemy for years. I do a painting called Pink Clouds that is of the rooftops of Montmartre. It looks the way I feel. Out of the storm.

Saw Tom Waits on stage. He sang, “If I exorcise my devils, well my angels may leave too.” I used to think that too. I don’t anymore. Suffering is not imperative. Being cynical is a cop-out. Hip negativity is just another form of conformity. If I feel the world is horrible, to be horrible myself would just be adding to the problem. The path of least resistance would be to submit to the inevitable course, and just become another fatality of bohemia’s wicked ways. As if I was passively going along with the downward flow. That’s not me, not who I was, not who I want to be. I have a choice in the matter. I can fight back. Wouldn’t the brave option be to try to live a positive life? Wouldn’t that be rebellion?

December 1980

I was interviewed by Patrick Roques for Vacation magazine out of San Francisco. Article called “The New Romantic.” I told some of my ghost stories. Talked about how misconceptions can be an asset. Bohemia. The nobility of being a painter. I did another interview with an artsy magazine out of Belgium called Soldes, with some nice photos. The interpreter was an English painter, Michael Bastow, who lives in Paris. Terrific draftsman. We become pals.

December 8, 1980

Terry and I were having a hamburger up on Columbus Avenue. I saw John Lennon’s face on the TV above the bar, sound off. He’s always in the news because of his Double Fantasy album. That album about the bogus love affair between him and Yoko. We pay up and walk down the avenue approaching Seventy-second Street. A madman is screaming in the street. At Seventy-second, I look east and see a small group of people congregated in front of the Dakota. Uh-oh. We walk over. People are crying. Yellow police tape and squad cars. John’s been shot. They’ve got the assassin, just a kid from Hawaii. A very strange vigil begins, as more and more mourners show up. It’s incredibly sad.