In 1968, with the Democratic Party sharply divided over the Vietnam War, Richard Nixon narrowly won the presidency. Most conservatives had supported him, albeit reluctantly, in hopes of gaining influence over his policies. Few Republicans could stomach the third-party campaign of Alabama governor George Wallace, whose rage-filled populist message gained 13.5 percent of the popular vote. But Nixon came into office with big Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress. Even if he had wanted to move to the right, he would have been unable to do so. Instead, Nixon pursued a rather liberal agenda at home, expanding the welfare and regulatory state. He intensified the bombing in Vietnam, while his national security adviser, and later secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, opened negotiations with North Vietnam. At the same time, Nixon entered into a new arms-control agreement with the Soviet Union, the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks. Then, shortly before the 1972 election, Nixon announced he planned to open relations with mainland China.

These policies dismayed many GOP conservatives. But the primary challenge to Nixon mounted by the new American Conservative Union failed miserably. Nixon easily won renomination and went on to swamp George McGovern, his Democratic opponent. Two years later, Nixon’s involvement in the Watergate scandal forced his resignation. New president Gerald Ford followed a moderate course that made him seem impervious to the rumblings of the right wing in his party.

In the mid-1970s, conservatives were a distinct minority within the Republican Party, but they were beginning to build an institutional foundation for their movement. They expanded the American Enterprise Institute, founded in the early 1940s, to provide conservative policy analysis. In 1973 conservative foundations such as the Scaife Fund, the John M. Olin Foundation, and the Bradley Foundation, and wealthy benefactors such as beer magnate Joseph Coors supported the establishment of the Heritage Foundation. These think tanks added intellectual firepower to the conservative resistance to the modern liberal state.

The founding of the magazine Public Interest by New York intellectual Irving Kristol in 1965 helped fuel the intellectual challenge to liberalism. Kristol viewed the Public Interest as an antidote to what he considered the increasing utopianism of leftist thinkers. The magazine attracted contributors who had become disgruntled with Johnson’s Great Society, including Daniel Moynihan, Nathan Glazer, James Q. Wilson, Edward C. Banfield, and Aaron Wildavsky. These scholars, many of them social scientists, criticized programs devised by what they called the “new class” of fashionable leftists and government bureaucrats. Similar criticisms emerged in the Jewish opinion magazine Commentary, edited by Norman Podhoretz.

Although not uniformly conservative in their political outlooks, the most prominent writers for the Public Interest and Commentary became known as “neoconservatives,” former liberals who rejected social experimentation, affirmative action, and moral relativism. They also supported a vigorous American foreign policy backed by a strong national defense to meet what they perceived as a heightened Soviet threat.

More traditional conservatives built a powerful movement to oppose the equal rights amendment (ERA) that Congress had passed in 1972—a victory for feminists. The ERA seemed to be headed toward easy ratification by the states until veteran right-wing activist Phyllis Schlafly organized a movement to stop it. She argued that the amendment would allow the drafting of women into the military, provide abortion on demand, legalize gay marriage, and weaken legislation protecting women in the workplace and in marriages. Schlafly organized a coalition of traditionalist Catholics, evangelical Protestants, Mormons, and orthodox Jews into a grassroots movement that helped stop the ERA from being ratified.

Other conservative activists—including Paul Wey-rich, fund-raiser Richard Viguerie, Howard Phillips, and Republican strategist Terry Dolan—saw potential in Schlafly’s success. They mounted a challenge to the GOP establishment through grassroots action on other “social issues,” such as opposition to abortion and gay marriage, and support for school prayer. Calling themselves the New Right, these activists brought new organizing and fund-raising prowess to the conservative cause.

With conservative activism growing, Ronald Reagan challenged Ford for the presidential nomination in 1976. He was unsuccessful, but Ford’s narrow defeat by Jimmy Carter that year put Reagan in position to win the party’s nomination four years later. White evangelical voters moved away from Carter, a southern Baptist Democrat, during his presidency; a key turning point was the Internal Revenue Service’s 1978 ruling to deprive all private schools established after 1953 of their tax-exempt status if they were found guilty of discriminatory racial practices. Along with Carter’s support for abortion rights, this decision rallied many evangelicals into supporting ministers Jerry Falwell and Tim LaHaye, who headed a new organization, the Moral Majority, that vowed to bring “traditional morality” back to government.

Conservatives exerted their influence in the 1978 midterm elections through the Committee for the Survival of a Free Congress and the National Conservative Political Action Committee. Although the South did not go fully Republican that year, history professor Newt Gingrich won election in Georgia, and, in Texas, Ron Paul won back a seat in Congress he had lost to a Democrat in 1976. At the same time, in California, voters ratified the Jarvis-Gann initiative, Proposition 13, cutting property taxes.

In 1980 Reagan won the Republican nomination and defeated Carter in the general election. The conservative standard bearer carried every region and every major constituency except Hispanics and African Americans. He won most southern states by 5 percentage points, and cut heavily into the blue-collar vote in the North. Republicans also won a majority of Senate seats for the first time in almost 30 years and made big gains in the House of Representatives. It was a significant victory for conservatives after 35 years of struggle.

During the next eight years, Reagan redefined the tone and nature of political discourse, although he had to compromise with a Democratic House throughout his term in office. Reagan failed to reshape the federal bureaucracy that sheltered liberal programs but did accomplish a good deal that delighted conservatives. The Economic Recovery Tax Act provided the largest tax decrease in history by reducing capital gains taxes and inflation-indexed tax rates. He continued Carter’s policy of deregulation, enacting major monetary and banking reform. He ordered staff cuts in the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Reagan’s administration supported efforts to restrict legalized abortion and to allow prayer in public schools, but these measures failed to pass in Congress. Reagan also initiated a massive increase in the defense budget and, in 1983, announced the Strategic Defense Initiative, an antimissile defense system based in outer space, which drew widespread protests from peace activists and liberal columnists.

The conservative president also waged what was, in effect, a proxy war against the Soviet Union. With the support of the AFL-CIO, the Vatican, and European trade unions, the United States assisted the anti-Communist labor movement Solidarity in Poland. The Reagan administration also aided “freedom fighters” in Central America, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Central America, and provided training and military assistance to Islamic forces opposed to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Reagan’s policy toward the Soviet Union combined militant engagement and arms reduction. This policy, which appeared inconsistent to his opponents, followed a conservative strategy captured in the slogan “peace through strength.” In pursuit of this aim, Reagan opposed calls by peace activists for a “nuclear freeze” on the development of new weapons and the deployment of Pershing II intermediate missiles in Europe. In a series of bilateral summit meetings from late 1985 through late 1988, Reagan and Soviet leader Premier Mikhail Gorbachev reached agreements that essentially brought an end to the cold war.

Conservatives found in Reagan an articulate and popular spokesman for their principles. While they sometimes criticized him as being overly pragmatic—raising taxes in 1983 and 1984, and failing to push for antiabortion legislation—he still left office as the hero of their movement. Reagan had succeeded in making conservatism a respectable political ideology in the nation as a whole.

Reagan’s successor, George H. W. Bush, sought to turn the Republican Party to the center while maintaining his conservative base. This proved to be a cumbersome political act that betrayed a lack of principle. Bush seemed more involved in foreign than domestic policy: he ordered a military incursion in Panama to overthrow a corrupt dictatorship and then mobilized international support for military intervention in Iraq following its invasion of neighboring Kuwait. At home, Bush supported such Democratic measures as a ban on AK-47 assault rifles, the Americans with Disabilities Act, and a large tax hike for wealthy Americans. To fill two openings on the Supreme Court, he named David Souter, who turned out to be a liberal stalwart, and Clarence Thomas, a conservative whose nomination became controversial when a former employee, Anita Hill, accused him of sexual harassment.

In the general election of 1992, Bush sought desperately to regain his conservative base. He invited conservative columnist Patrick Buchanan, who had challenged him in the primary campaign, to address the Republican convention. Buchanan’s speech declared that the Democratic Party nominee Bill Clinton and his wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, would “impose on America . . . abortion on demand, a litmus test for the Supreme Court, homosexual rights, discrimination against religious schools, women in combat. . . .” Buchanan’s talk of a “culture war” was received enthusiastically by evangelical conservatives, but it alienated mainstream voters and probably helped defeat Bush’s bid for reelection that fall.

Conservatives viewed Clinton as a baby boomer who had protested the war in Vietnam, repelled the military, and supported abortion. Conservatives seized on Clinton’s proposal, as president-elect, to lift the ban on gay men and lesbians in the military, a quiet campaign promise he had to back away from under a barrage of criticism from the right. This proved to be the opening round in a well-orchestrated conservative assault that put the Clinton administration on the defensive and defeated the president’s proposal for a universal health care system that the first lady had largely devised.

As the midterm election of 1994 drew near, conservatives led by Representative Newt Gingrich of Georgia organized a group of young Turks in the House to retake Republican control of that body for the first time since 1952. They drafted the Contract with America, which pledged 337 Republican candidates to a ten-part legislative program, including welfare reform, anticrime measures, a line-item veto, regulatory reform, and tax reduction. The contract notably ignored such emotional issues as abortion, pornography, and school prayer. The Contract with America drew enthusiastic response from the conservative media, especially Rush Limbaugh, whose radio program appeared on 600 stations with 20 million weekly listeners. On Election Day, Republicans captured both houses of Congress with a 230–204 majority in the House and eight new Senate seats.

Clinton nonetheless won reelection in 1996 against the weak campaign of Senator Robert Dole and survived a sexual scandal involving a White House intern that led the Republican House to impeach him. The Senate failed to convict, and Republicans lost seats in the 1998 election, shocking conservatives who had assumed that “immorality in the Oval Office” would benefit their cause. Many Republicans blamed Gingrich for the loss, and shortly after the election, he resigned from the House.

The Clinton scandal carried into the 2000 presidential race, in which Republican Texas governor George W. Bush defeated Democratic Vice President Al Gore in the closest election in modern U.S. history. Bush lost the popular vote, but he gained Republican support among observant conservative Christians, especially evangelical Protestants and Roman Catholics. Although Pat Robertson’s Christian Coalition had waned in influence, a strong religious network made direct contact with voters through voter guides and pastoral commentary. Much of this strategy of targeting key voters was the brainchild of political consultant Karl Rove.

The world of politics—and the fate of Bush’s presidency—was transformed by the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Bush’s resolute stance won him enormous popularity, and Congress passed a series of emergency measures, including the Combating Terrorism Act and the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT) Act, which expanded the surveillance powers of federal agencies. Civil libertarians worried that this legislation extended too much power to the federal government at a cost to personal liberties. But it underlined the Republican advantage on the issue of national security and helped the party gain seats in Congress in the 2002 election—and also gave the president the political support he needed to invade Iraq in early 2003. Although the war did not proceed as planned, Bush won a second term in 2004 against Democrat John Kerry, due in large part to his image as the leader of the so-called War on Terror. For the first time in decades, conservative Republicans were in firm control of the White House and Capitol Hill.

The triumph was brief, however. Soon after Bush’s reelection, the continuing bloodshed in Iraq and the administration’s fumbling of relief efforts following Hurricane Katrina led to the beginning of his steep decline in approval polls, and he never recovered. A series of lobbying and fund-raising scandals involving Republican leaders in Congress and a well-organized grassroots campaign allowed Democrats to regain control of the House and the Senate in 2006. The Republican decline continued in 2008, when Democrat Barack Obama was elected to the White House and Democrats retained control of Congress. Although Obama only won 1.5 percent more of the popular vote than George W. Bush had in 2004, Republicans were soundly defeated. Especially disturbing for the party was the defection of nearly 20 percent of Republicans who had voted for Bush. Moreover, Obama won among independents, women, and the young, while white males, white Catholics, and seniors barely supported the GOP presidential candidate, John McCain. No longer were the Republicans a majority party.

Conservatism has been a dynamic political movement through most of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, continually shaped both by new ideas and ideological tensions. Before World War II, it consisted mainly of a defense of the cultural traditions of Western civilization and of laissez-faire and free markets. Pre–World War II conservatives staunchly defended localism, a strict adherence to the Constitution, and distrust of strong executive power in the face of profound technological and political change.

The cold war altered conservatism profoundly. Most conservatives supported cold war containment and extended the fear of communism into the domestic arena. In order to combat liberalism at home and communism abroad, it was necessary for conservatives to enter politics and not just to plead for their views in the intellectual realm. From the 1950s to the end of the cold war, conservatives constructed a political movement based on firmly opposing state-building tendencies at home while fighting communism abroad. There were inherent contradictions in such a policy, but conservatives focused on policies and programs designed to fulfill these two goals. The end of the cold war deprived conservatives of an enemy and left those critical of cold war conservatism, such as journalist Patrick Buchanan, to revive Old Right isolationism in the post-9/11 world.

Modern liberalism proved to be a formidable opponent; despite Republican victories, the modern welfare and regulatory states were not easily dismantled. Nonetheless, the conservative ascendancy within the Republican Party and in the electorate during the last half of the twentieth century led to significant political and policy changes. Conservatives were able to mobilize large number of voters to their cause. Even as late as 2008, when conservatives appeared to be in a downswing, nearly 35 percent of the electorate identified themselves as “conservative.” More important, while conservatives acting through the Republican Party were not able to scale back Social Security, Medicare-Medicaid, education, or environmental protection, they won notable victories in strengthening national defense, reforming welfare policy, restricting reproductive rights, reinvigorating monetary policy, deregulating major industries, and appointing conservative federal judges.

As conservatives sought to regroup after the 2008 defeat, they could take little consolation in the historical reminder that Republican success often followed Democratic mistakes in office. Given the severity of the financial meltdown and the international threats of rogue nations, oil shortages, nuclear proliferation, and military involvement in the Middle East and Afghanistan, even the most partisan-minded Republicans hoped that their return to office would not be built on a failed Obama presidency. While partisan differences would not be ignored, Democrats and Republicans, progressive and conservatives alike, understood that above all else, as Abraham Lincoln said in 1858, “a house divided against itself cannot stand.”

See also anticommunism; anti-statism; economy and politics; liberalism; Republican Party.

FURTHER READING. Donald T. Critchlow, The Conservative Ascendancy: How the GOP Right Made Political History, 2007; Brian Doherty, Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement, 2007; Lee Edwards, The Conservative Revolution: The Movement that Remade America, 1999; Bruce Frohnen, Jeremy Beer, and Jeffrey O. Nelson, eds., American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia, 2006; F. A. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom, 1944; Steven F. Hayward, The Age of Reagan: The Fall of the Old Liberal Order, 1964–1980, 2001; George H. Nash, The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America: Since 1945, 3rd ed., 2006; Gregory L. Schneider, The Conservative Century: From Reaction to Revolution, 2009; Jonathan M. Schoenwald, A Time for Choosing: The Rise of Modern American Conservatism, 2001; Henry M. Wriston, Challenge to Freedom, 1943.

DONALD T. CRITCHLOW AND GREGORY SCHNEIDER

In 1984 President Ronald Reagan cruised to reelection in the second largest electoral landslide in American history. The next year, before a cheering crowd of conservatives, Reagan declared, “The tide of history is moving irresistibly in our direction. Why? Because the other side is virtually bankrupt of ideas. It has nothing more to say, nothing to add to the debate. It has spent its intellectual capital.” It was a bold proclamation by a leader who had proved beyond debate that conservative ideas could have mass appeal.

But was Reagan right? On the one hand, liberals had apparently lost the war of ideas. By the mid-1980s, conservatives had amassed an impressive stockpile of ideological weapons thanks to a well-financed and well-coordinated network of private foundations, policy journals, and think tanks. On the other hand, Reagan’s explanation downplayed a host of other political, historical, economic, personal, and structural factors. And whether the “tide of history” was irresistible or irreversible was by no means a foregone conclusion.

Nevertheless, conservatives became dominant in the two decades immediately following 1984, at least in electoral terms. The Republicans won five of the seven presidential elections after 1980, when they also captured the Senate for the first time since 1952. The Democrats recaptured the Senate in 1986, but, eight years later, the Republicans reclaimed it and, for the first time since 1954, also took command of the House. For most of the next decade, the GOP had effective control of Congress. Moreover, by 2004 the party as a whole had veered sharply to the right, with conservatives in charge and moderates on the verge of extinction.

The conservative ascendance was not, however, preordained. Few could or would have predicted it in the wake of the Watergate scandal. An assassination attempt against Reagan in March 1981 dramatically boosted his popularity and contributed significantly to passage of his tax bill, the signature achievement of his first term. The terrorist attacks in September 2001 transformed the presidency of George W. Bush and restored national security as the preeminent issue in American politics. They also enabled the Republicans to extend their control of Congress in 2002 and made possible Bush’s narrow reelection in 2004.

Nor was the conservative ascendancy complete by 2004. By some measures, public opinion had shifted to the right since 1980. President Bill Clinton, for instance, was the first Democrat since Franklin Roosevelt to win consecutive terms. But he also achieved his greatest popularity after he proclaimed “the end of welfare as we know it” and “the era of big government is over.” By other measures, the country had remained in place or moved to the left. Even on controversial social issues like homosexuality, the data were mixed, with greater tolerance counterbalanced by strong opposition to gay marriage. On balance, the evidence suggests that while most Americans object to big government in principle, in practice they accept and approve of federal programs like Social Security that benefit the great majority. As a result, the bureaucracy has grown steadily, which in turn has led to a debate among conservatives between “small-government” purists, who are usually not elected officials, and “big-government” politicians like George W. Bush, who supported a major expansion in Medicare benefits.

By 2004 no mass or permanent realignment of partisan preferences had taken place. The conservatives had won many electoral victories since 1980, but the nation remained divided and polarized. In a sense, the situation was little changed from 2000, when Bush and Vice President Al Gore, the Democratic nominee for president, fought to a virtual stalemate, the Senate was split 50-50, and the Republicans retained a slim majority in the House. Nonetheless, the New Right had eclipsed the New Deal political coalition and brought the Democratic era in national politics to a clear end. What made the conservative ascendance possible, and what sustained it?

Scholars disagree as to whether the New Deal political coalition of white Southerners, urban workers, small farmers, racial minorities, and liberal intellectuals was inherently fragile or whether the 1960s was the moment of reckoning. But the immediate causes of Reagan’s victory in 1980 are less debatable. Most important was the failure of the Carter presidency. At home, the “misery index” (the combined rates of inflation and unemployment) stood at more than 20 percent. Abroad, Soviet troops occupied Afghanistan, and American hostages were held captive in Tehran. The future seemed bleak, and the president appeared to be unable to provide confident or competent leadership. What the White House needed was a new occupant—the main question was whether Reagan was a conservative ideologue or capable candidate.

Reagan’s personality proved critical during the campaign. A gifted and affable performer, he was able to cross the “credibility threshold” in the presidential debates and reassure Americans that he was a staunch anti-Communist, not an elderly madman bent on nuclear confrontation with the Soviet Union. On the contrary, Reagan appeared vigorous, warm, principled, and optimistic—he promised that America’s best days lay in the future, not the past. He also asserted that the weak economy was the fault of the government, not the people. Above all, Reagan was the smiling and unthreatening face of modern conservatism.

A third cause of conservative ascendancy was the tax revolt of the late 1970s. As inflation mounted, the middle class was trapped between stagnant incomes and rising taxes. In 1978 California voters approved Proposition 13, which slashed property taxes and triggered a nationwide movement toward such relief. The tax issue helped unite a contentious conservative coalition of libertarians, traditionalists, and anti-Communists. It also crystallized opposition to the liberal welfare state and gave Republicans a potent weapon to aim at government programs previously viewed as politically untouchable. In the coming decades, tax cuts would become conservative dogma, the “magic bullet” for growing the economy, shrinking the bureaucracy, and harvesting the votes of disgruntled citizens.

A final cause was the emergence of religious conservatives as a significant bloc of Republican voters. Prior to the 1960s, many evangelical Christians either avoided the political world or divided their votes between the parties. But in 1962, the Supreme Court ruled in Engel v. Vitale that the First Amendment banned even nondenominational prayer in the public schools. Then the sexual revolution and the women’s movement arrived amid the social upheaval of the decade. In 1973 Roe v. Wade made abortion an important issue, and in 1978 the Internal Revenue Service threatened to repeal the federal tax exemption for racially segregated Christian schools. The latter action outraged evangelicals, especially the Reverend Jerry Falwell, who in 1979 founded the Moral Majority, which quickly became a powerful force within the New Right. In 1980 Reagan received 61 percent of the fundamentalist vote; by comparison, Jimmy Carter (a born-again Christian) had received 56 percent in 1976. By 2004 the most reliable Republican voters were those Americans who went to church more than once a week.

At first the conservative momentum continued under Reagan’s successor, Vice President George H. W. Bush, who easily won election in 1988. But he lacked the personal charisma and communication skills that had enabled Reagan to attract moderates and bridge divisions on the right. The end of the cold war also removed a unifying issue from the right’s repertoire and shifted the political focus from national security (a Republican strength) to economic security (a Democratic strength). The fall of the Soviet Union meant, moreover, that conservatives could no longer paint liberals as soft on communism—a deadly charge in American politics since the 1940s. Finally, Bush made a critical political error in 1990 when he broke his “read my lips” campaign pledge and agreed to a tax hike. According to most economists, the increase was not a significant factor in the recession of 1991–92. But many conservatives today trace the start of what they see as the betrayal or repudiation of the “Reagan Revolution” to that fateful moment.

In 1992 Clinton focused “like a laser beam” on the poor state of the economy and, thanks in large measure to the presence of independent candidate Ross Perot on the ballot, defeated Bush. Then the Democrat rode peace and prosperity to reelection in 1996. Clinton infuriated conservatives because he usurped what they saw as their natural claim to the White House, he seemed to embody the counterculture values of the 1960s, and was a gifted politician who co-opted many of their issues. In many respects, Clinton truly was a “New Democrat,” who supported free trade, a balanced budget, and the death penalty. Nevertheless, even he was unable to reverse the conservative ascendance—at best, he could only restrain it after the Republicans took control of Congress in 1994.

In the 1990s, conservatives continued to set the political tone and agenda by demonstrating that they were masters of coordination and discipline. In Washington, they gathered every Wednesday at a breakfast sponsored by Americans for Tax Reform and a lunch sponsored by Coalitions for America to discuss issues, strategies, and policies. At the same time, the Club for Growth targeted moderates (deemed RINOs—Republicans in Name Only) and bankrolled primary challenges against them. And after 1994, members of Congress received committee chairs based on loyalty to the leadership, not seniority, a change spearheaded by House Speaker Newt Gingrich of Georgia. By 2000 conservative control and party discipline were so complete that Bush never had to employ the veto in his first term—a feat not accomplished since the presidency of John Quincy Adams.

The conservative movement was also flush with funds. Much Republican money came in small contributions from direct mailings aimed at true believers, but large sums came from two other sources. The first was corporate America, which in the 1970s found itself beset by foreign competition, rising wages, higher costs, and lower profits. In response, it created lobbying organizations like the Business Roundtable, formed political action committees, and channeled campaign contributions in ever larger amounts to conservative politicians, who in turn made government deregulation, lower taxes, and tort reform legislative priorities in the 1980s. The second source of funds was lobbyists, who represented many of the same corporations. After the GOP rout in 1994, House Majority Whip Tom DeLay of Texas initiated the “K Street Project,” whereby lobbyists hoping to do business on Capitol Hill were pressured into making their hiring practices and campaign contributions conform to Republican interests.

At the same time, corporate boards and private foundations invested heavily in institutions like the American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation, which had immense influence in policy design, both domestic and foreign. These think tanks constituted a veritable shadow government for officials between positions or awaiting an opportunity. They also acted as incubators of ideas and command posts for policy research in the ideological war that conservatives fought against liberals.

The struggle was waged on several fronts. On the ground, conservatives proved expert at mobilizing their base, which became increasingly important to both parties as the number of undecided voters shrank in the highly partisan political climate of the 1990s. In 2004, for example, George W. Bush won largely because the Republicans recruited 1.4 million volunteers, who boosted the president’s popular vote by 20 percent (including 4 million Christians who had voted in 1996 but not in 2000). By comparison, in 2004 the Democrats raised their vote totals by 12 percent over 2000, which was impressive but insufficient. On the air, the conservatives also exploited every advantage at their disposal. In 1987 the abolition of the Fairness Doctrine, which had required broadcasters to provide “equal time” to alternative views, opened the door to right-wing talk radio. Enter Rush Limbaugh, a disk jockey from Missouri, who by the mid-1990s had inspired countless imitators and was reaching 20 million devoted listeners (known as “dit-toheads”) daily on 660 stations across the nation. And, by 2000, FOX News, with a strong conservative slant, had surpassed CNN to become the most popular news channel on cable television.

Another source of strength for Republicans was the weakness of the Democrats, who lacked a clear vision or coherent set of core principles. The party was deeply divided between “upscale Democrats” (well-educated professionals who were more socially liberal) and “downscale Democrats” (economically marginal workers and minorities who were more socially conservative). Moreover, historical memories had faded—by 2002 less than one in ten voters could personally recall the Great Depression and New Deal. Labor unions, a pillar of the party, had also eroded in size and influence. In 1960, 40 percent of the workforce was unionized; by 2000, the figure was 14 percent and falling. In addition, the once Solid South was now reliably Republican. In the seven presidential elections between 1980 and 2004, Republican candidates lost a combined total of just five southern states to Democratic candidates.

Even the much touted “gender gap” provided little solace to the Democrats. Since 1980, when it first appeared, the party attracted women in growing numbers. By 2004, the Democrats were majority female and the Republicans were majority male. The problem for Democrats was that the exodus of men, especially working-class white Southerners, exceeded the influx of women. That was the real cause of the gender gap, which in 2004 was also a marriage gap (55 percent of married women voted for Bush, while 62 percent of single women voted against him). Nevertheless, if men and women had switched partisan allegiances at the same rate after 1980, Bush would have lost in both 2000 and 2004.

After 2004 many Democrats were in despair. Bush, whom few experts had predicted would win in 2000, had again defied the odds by surviving an unpopular war, a weak economy, and soaring deficits. The Republicans had also extended their control of Congress and built a well-financed party structure. In the aftermath of the 2004 election, White House political adviser Karl Rove boasted that the United States was in the midst of a “rolling realignment.” Eventually, the Republicans would become the dominant party, he predicted, as they had in 1896 and the Democrats had in 1932. It was merely a matter of time, especially if the terrorist threat continued to make national security a priority.

Some Democrats, however, were not disheartened. Both elections were close calls, and in 2004 Bush had a considerable advantage as an incumbent wartime president. Moreover, some long-term demographic and technological developments seemed to favor the Democrats. The Internet had filled their war chest with vast sums, and bloggers had reenergized intellectual debates among the party faithful, even if new groups like MoveOn.org and America Coming Together were less successful at mobilizing voters on election day. The increasing number of well-educated working women and Latino voters also seemed to bode well for the Democrats, as did the steady growth in unmarried and secular voters, who seemed to be more liberal in their outlook.

Nevertheless, the Republicans continued to have structural and ideological advantages. In the Electoral College, the less populated “red states” still had disproportionate influence, raising the bar for Democratic candidates. And in congressional districts, partisan gerrymandering kept most Republican districts intact. In 2004, for example, Bush carried 255 districts—almost 59 percent—compared with his popular vote total of less than 52 percent. In addition, the Republican Party’s moral conservatism and entrepreneurial optimism seemed likely to appeal to a growing number of Latino voters, assuming that the immigration issue did not prove divisive in the long term.

But, in 2006, the Democrats surprised themselves and the pundits by retaking the House and Senate, as undecided voters punished the party in power and negated the base strategy of the Republicans by overwhelmingly blaming them for political corruption and the Iraq War. Then, in 2008, the Democrats solidified their control of Congress and recaptured the White House when Senator Barack Obama defeated Senator John McCain in a presidential race dominated by voter discontent with the Bush administration and the most serious financial crisis since the Great Depression. The tide of history that Reagan hailed in 1985 had ebbed. Republican hopes for a major realignment had faded. But it was too soon to tell whether the conservative ascendancy had come to a lasting end.

See also conservatism; Democratic Party, 1968–2008; Republican Party, 1968–2008.

FURTHER READING. Donald Critchlow, The Conservative Ascendancy: How the GOP Right Made Political History, 2007; Thomas B. Edsall, Building Red America: The New Conservative Coalition and the Drive for Permanent Power, 2006; Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson, Off Center: The Republican Revolution and the Erosion of American Democracy, 2005; John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge, The Right Nation: Conservative Power in America, 2004; Michael Schaller and George Rising, The Republican Ascendancy: American Politics, 1968–2001, 2002; Thomas F. Schaller, Whistling Past Dixie: How Democrats Can Win without the South, 2006.

MICHAEL W. FLAMM

The years between World War I and the New Deal are popularly known as the Roaring Twenties because of the era’s tumultuous social and cultural experimentation and spectacular economic growth. The cultural upheaval—from the Harlem Renaissance to jazz, and from flappers to speakeasies—stands in contrast to the period’s conservative politics. The decade witnessed a muting of the Progressive Era voices that had sought to end the abuses of unregulated capitalism through industrial regulation and reform. Presidents Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover emphasized a limited role for the regulatory power of the federal government and the importance of efficiency, individualism, as well as support for business. Calvin Coolidge summed up the dominant ethos in the White House with his statement, “The business of America is business.”

Despite the support for business fostered in the halls of the White House and a broad segment of Congress, the 1920s did not simply represent a discontinuous period sandwiched between two eras of reform (the Progressive Era and the New Deal). Indeed, the decade opened with major victories for two important reform movements. With the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, women’s rights advocates had won their long battle for suffrage. The national electorate expanded dramatically with female citizens no longer excluded from the right to vote on the basis of gender. In the wake of woman suffrage, advocates for women’s equality struggled to define their movement. Alice Paul and the National Women’s Party battled for the passage of an equal rights amendment, while other activists pressed on for protective legislation, winning a victory in 1921 when Congress passed a bill providing funds for prenatal and child health care. A second reform movement, that of temperance, triumphed with the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment, outlawing the sale, manufacture, and transportation of liquor, to take effect in January 1920. The radical experiment with national Prohibition, the law of the land until 1933, helped to lay the groundwork for the expansion of the federal government that took place during the New Deal. In addition, Hoover’s conservative variant of progressivism included an important role for the federal government in providing knowledge, expertise, and information to business to shore up economic growth. Indeed, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first New Deal had much in common with Hoover’s effort to utilize the state in cooperation with business to mitigate the severe economic crisis that shook the nation during the Great Depression.

After the upheavals of the “Great War,” the tumultuous global ramifications of the Russian Revolution, and the defeat of Woodrow Wilson’s postwar internationalism, Warren Harding’s calls for a “return to normalcy” resonated with many voters. In November 1920, Harding won a lopsided victory over Democrat James M. Cox of Ohio, and the Republicans solidified the hold on Congress that they had won in 1918. Harding came to the presidency with a long record of public service but an undistinguished record as a senator. The policies of his administration, however, as well as those of the Supreme Court, demonstrated a strong orientation toward the business community. With the federal government’s pro-business orientation, emboldened industrialists undertook a successful counterattack against the gains labor had made during World War I. The great labor strikes that rocked the nation in 1919 had ended in defeat. By 1923, union membership fell to 3.6 million from more than 5 million at the end of the war.

Falling union membership mirrored developments in political participation more broadly. Voter turnout rates were low throughout the decade, averaging around 46 percent. Progressive innovations such as nonpartisan elections undercut party organization and weakened party identification. The non-voters tended to be the poor, and new voters such as women, African Americans, and naturalized immigrants. Only in 1928 did participation rise to 56 percent as the volatile issues of religion, ethnicity, and Prohibition mobilized the electorate.

With Harding’s death on August 2, 1923, Vice President Calvin Coolidge succeeded to the presidency. His reserved New England demeanor marked a sharp break from Harding’s outgoing midwestern charm, but their different personalities belied a common approach toward government. As Harding before him, Coolidge emphasized efficiency, limited government, and strong praise for capital. Coolidge summed up this ethos when he remarked, “The man who builds a factory builds a temple. The man who works there worships there.” These notions seemed to resonate with large numbers of Americans in a period of economic expansion and growing affluence. While the decade had opened in recession, from 1922 to 1929, national income increased more than 40 percent, from  60.7 billion to

60.7 billion to  87.2 billion. Automobiles, construction, and new industries like radio fueled an economic boom. The number of passenger cars in the United States jumped from fewer than 7 million in 1919 to about 23 million in 1929. Radio, getting its start in 1920, was a household item for 12 million Americans by 1929. The availability of new products, installment buying, and an increasingly national advertising industry fueled a mass consumption economy just as increased leisure, radios, and movies generated a mass culture.

87.2 billion. Automobiles, construction, and new industries like radio fueled an economic boom. The number of passenger cars in the United States jumped from fewer than 7 million in 1919 to about 23 million in 1929. Radio, getting its start in 1920, was a household item for 12 million Americans by 1929. The availability of new products, installment buying, and an increasingly national advertising industry fueled a mass consumption economy just as increased leisure, radios, and movies generated a mass culture.

Economic growth and mass consumption went hand in hand, however, with the increasing maldistribution of wealth and purchasing power. Indeed, about one-third of families earned less than the minimum income estimated for a “decent standard of living.” Those Americans working in what were then known as the “sick industries,” such as textile and coal, along with the nation’s farmers, failed to benefit from the economic gains of the period. Progressive reformers continued to criticize the consolidation of private capital and the inequalities of income. Eugene Debs, sentenced to ten years in prison under the Seditions Act of 1918, ran as Socialist Party candidate for president in 1920 (from federal prison) and won close to a million votes. In 1924, Robert F. Lafollette, a senator from Wisconsin, led the third-party Progressive ticket, mobilizing reformers and labor leaders as well as disgruntled farmers. The Progressive Party called for the nationalization of railroads, the public ownership of utilities, and the right of Congress to overrule Supreme Court decisions. Lafollette won 5 million popular votes but carried only his home state of Wisconsin.

While progressives and radicals chipped away at the sanctified praise of business voiced by three Republican administrations, their criticisms were shadowed by far more powerful reactions against the tide of urbanization, secularization, and modernism. Protestant fundamentalist crusades against the teachings of Darwinism and modernism in the churches culminated in the State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes trial (better known as the “Scopes Monkey Trial”) in 1925. Riding a tide of backlash against urban concentrations of immigrants, Catholics, and Jews as well as militant Prohibitionist anger with the unending flow of illegal drink, the Ku Klux Klan mushroomed throughout the nation, becoming a significant force in politics in such states as Indiana, Ohio, and Colorado.

During its heyday in the mid-1920s, between 3 to 5 million people joined the ranks of the hooded Klan, making it one of the largest and most influential grassroots social movements in twentieth-century America. Systematically targeting African Americans, Catholics, Jews, and foreigners as threats to Americanism, the Klan drew from a broad group of white Protestant men and women throughout the Midwest, West, and South through its promises to stave off a drift away from the values of small-town Protestant America. The Klan sold itself as an organization devoted to “law and order” by promising to rid America of liquor. Prohibition intersected closely with the Klan’s larger nativist, anti-Catholic agenda since many ethnic Catholic immigrants blatantly flouted the law. By organizing drives to “clean up” communities and put bootleggers out of business, the Klan became a popular means of acting on militant temperance sentiments.

Prohibition was a radical experiment and, not surprisingly, it sharpened key cultural divides of the era. The Eighteenth Amendment became effective on January 17, 1920, after ratification of all but two states (Connecticut and Rhode Island). Outlawing the sale, manufacture, and transport of alcohol, it was, one contemporary observed, “one of the most extensive and sweeping efforts to change the social habits of an entire nation in recorded history.” It was an astonishing social innovation that brought with it the greatest expansion of federal authority since Reconstruction. While the Republican and Democratic parties had avoided taking official positions on the subject, during the 1920s, national Prohibition became a significant bone of contention, particularly for the Democratic Party, solidifying divisions between the Democratic Party’s rural, “dry,” Protestant wing and its urban, Catholic “wet” wing. The party’s two wings fought over nativism, the Klan, and Prohibition at its 1924 Convention. And by 1928, the party’s urban wet wing demonstrated its newfound strength when Alfred E. Smith became the Democratic presidential nominee.

For many of the nation’s immigrants, Prohibition was an affront to personal liberty, particularly since their communities were the special targets of law enforcement efforts to dry up the flow of bootleg liquor. As a result, it ignited a growing politicization of ethnic immigrant workers. While Prohibition made immigrant, urban, and ethnic workers aware of the dangers of state power, it had the far greater effect of leading many of these workers into the national Democratic Party. Catholic immigrant and New York governor Al Smith carried the country’s 12 largest cities, all rich in immigrants, and all of which had voted Republican in 1924. The Smith campaign forged an alignment of urban ethnic workers with the Democratic Party that was solidified during the New Deal. In their turn, the nation’s rural Protestant and dry Democrats dreaded the specter of a Catholic and wet urbanite in the White House. Their disdain for Smith led many to abandon their allegiance to the Democratic Party to vote for Hoover. As a result, Hoover won in a landslide, receiving 58 percent of the popular vote and 447 electoral votes to Smith’s 87. Hoover cut heavily into the normally Democratic South, taking the upper tier of the old confederacy, as well as Florida.

The third straight Republican to dominate the era’s national politics, Hoover had won the support of many progressive reformers, including settlement house leader and international peace advocate Jane Addams. Hoover championed a conservative variant of progressivism that flourished in the 1920s. While he refused to countenance public authority to regulate business, he hoped to manage social change through informed, albeit limited, state action. He championed the tools of social scientific expertise, knowledge, and information in order to sustain a sound economy. His desire to organize national policies on a sound basis of knowledge resulted in a major study called Recent Social Trends, a 1,500-page survey that provided rich data about all aspects of American life. As this social scientific endeavor suggests, Hoover drew from a broad font of progressive ideas but remained firm in his commitment to what he called “American Individualism.”

Hoover’s strong belief in limited government regulation went hand in hand with his embrace of federal authority to shore up Prohibition enforcement. To make clear that the federal government would not tolerate the widespread violations apparent almost everywhere, Hoover signed the Jones Act in 1929, a measure strongly backed by the Anti-Saloon League. The act raised a first offense against the 1929 Volstead Act to the status of a felony and raised maximum penalties for first offenses from six months in jail and a  1,000 fine to five years and a

1,000 fine to five years and a  10,000 fine.

10,000 fine.

An outpouring of protest undermined support for the Eighteenth Amendment. William Randolph Hearst, once a strong backer of national Prohibition, now declared that the Jones Law was “the most menacing piece of repressive legislation that has stained the statute books of this republic since the Alien and Sedition laws.” As the reaction to the Jones Act suggests, the “noble experiment” sounded a cautionary note about using the power of the state to regulate individual behavior.

But Prohibition’s repeal did not signify a broad rejection of federal government regulation. Rather, the great debate over the merits of Prohibition throughout the decade helped lay the ground for a greater legitimacy of state authority: The debate did not challenge the government’s right to regulate as much as it raised important questions over what its boundaries should be. Prohibition helped draw a thicker line between the legitimate arena of public government regulation and private behavior.

In the face of the increasingly dire economic circumstances at the end of the decade, the nation’s preoccupation with moral regulation appeared increasingly frivolous. The stock market, symbol of national prosperity, crashed on October 29, 1929. By mid-November, stock prices had plunged 40 percent. The crash intensified a downward spiral of the economy brought about by multiple causes: structural weaknesses in the economy, unequal distribution of income, and the imbalanced international economic system that had emerged from World War I.

Hoover put his conservative progressivism to the test during the downturn, and it proved inadequate for the scope of the crisis. He called on business to cooperate by ending cutthroat competition and the downward spiral of prices and wages. He proposed plans for public works to infuse money into the economy. And in 1932, he established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to provide emergency loans to ailing banks, building and loan societies, and railroads. Hoover’s embrace of government action was tethered, however, to his strong belief in voluntarism and, as a result, provided too little too late. His efforts, moreover, were directed for the most part toward business. While he did support federal spending to shore up state and local relief efforts, the sums were not enough. In 1932 a bitter and recalcitrant Hoover was trounced by the gregarious Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose declaration that the American people had “nothing to fear but fear itself” ushered in a new relationship of citizen to state and a new period of economic reform.

One of Roosevelt’s first acts in office was to sign the Beer and Wine Revenue Act, anticipating the repeal of national Prohibition and effectively ending the radical experiment. The experience of national Prohibition had highlighted the real danger posed to personal liberty by the linkage of “morality” and politics. By the 1930s, the federal government’s effort to dry up the nation and alter personal habits appeared increasingly absurd. Facing a grave economic crisis, the nation’s chastised liberals now concerned themselves with using the state to regulate capitalism and provide a minimal security net for Americans against the vagaries of the marketplace. During the New Deal, state regulation focused on economic life, replacing an earlier era of regulation of public “moral” behavior that had marked the Roaring Twenties.

See also Americanism; conservatism; consumers and politics; New Deal Era, 1932–52; Prohibition and temperance.

FURTHER READING. David Burner, The Politics of Provincialism: The Democratic Party in Transition, 1918–1932, 1986; Norman H. Clark, Deliver Us from Evil: An Interpretation of American Prohibition, 1976; Lizabeth Cohen, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939, 2nd ed., 2008; Alan Dawley, Changing the World: American Progressives in War and Revolution, 2003; Lynn Dumenil, Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s, 1995; Ellis Hawley, The Great War and the Search for a Modern Order, 1979; David Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945, 1999; David Kyvig, Repealing National Prohibition, 2000.

LISA MCGIRR

The oldest of the world’s effective written constitutions, the U.S. Constitution was designed in a convention in the summer of 1787, made public on September 17, and formally adopted with the ratification of New Hampshire on June 21 of the following year. It serves as the fundamental law determining the scope and limits of the federal government. But its origin lies in a perceived need to reform the “firm league of friendship” that held together the 13 original colonies in one nation, with “a more perfect Union.”

The Articles of Confederation, drafted during the opening stages of the war for independence, had established the first American Union. Less than a decade later, they were widely regarded as a failure. In the 1780s, the United States faced a number of critical international and interstate issues arising from the Revolution and the ensuing separation of the colonies from the British Empire. State governments refused to adhere to the peace treaty with Britain; Britain refused to give up military posts on U.S. territory; public creditors went unpaid; Indians attacked settlers and squatters occupied public lands; Spain closed the Mississippi to American commerce; and Britain banned American ships from trading with the West Indies and the British Isles.

Congress—the central government established by the Articles of Confederation—was unable to address these issues. It had neither money nor soldiers, only minimal administrative departments, and no court system. The Constitution aimed to change this situation. It was therefore a practical solution to immediate problems. But this should not detract from the achievement of the founders, for the difficulties were pressing and the stakes were high. In the minds of the reformers, the American Union had become so weak that the future of the nation as an independent confederation of republics was in doubt. Because republican rule on the scale attempted in the United States was a novel political experiment, the outcome of the American crisis had global significance. The success or failure of the reform would decide whether republican government—that is, popular self-rule for the common good—was viable. Ultimately, therefore, the framing and ratification of the Constitution should be understood as an attempt to secure republican government by means of a stronger union.

The reform of the Union was based on two fundamental premises: first, that the civic liberties and rights that Britain had threatened and the American Revolution defended could only be safeguarded under a republican form of government; second, that the American states could only be guaranteed a republican form of government by union. Union and liberty were therefore intimately linked in the political imagination of the founding generation as the preservation of liberty was the raison d’être of the Union.

In the present world of stable democracies and superpower republics, the notion that republics are inherently weak and unstable, and therefore difficult to maintain, does not come naturally. Early modern political theory, however, taught that republics were prone to internal dissension and foreign conquest. Republican citizens were freer than the subjects of monarchs, but this freedom made them hard to control and made it difficult for the government to command the social resources and popular obedience necessary to act forcefully against foreign enemies and domestic rebellion. Monarchies were therefore held to be better equipped than republics for securing the survival of the state. But the strength of monarchical rule rested on centralization of power at the cost of popular liberty. Political theory also taught that republican rule could be maintained only in states with a limited territory and a small and homogeneous population. Thus, the republic’s weakness came both from a necessary small size and the form of government.

Confederation provided a way out of this predicament. In the words of eighteenth-century French writer Baron Montesquieu, by joining together, republics could mobilize and project “the external force of a monarchy” without losing “all the internal advantages of republican government.” Confederation also provided protection against internal dissension, the other great threat to the republic. “If sedition appears in one of the members of the confederation,” noted Montesquieu, “the others can pacify it. If some abuses are introduced somewhere, they are corrected by the healthy part.” In important respects, the U.S. Constitution is the practical application of Montesquieu’s lesson.

The American states assumed independence and entered into union in a single political process. Work on an act of union was already under way when the states declared independence, but the Articles of Confederation were not finished until 1777 and took effect only with ratification by the thirteenth straggling member, Maryland, in 1781. Like the Constitution, the articles were both an agreement of union between the states and a charter for the central government created to realize the purposes of union. They aimed to provide the states with “common defense, the security of their Liberties, and their mutual and general welfare” (Article III). To this end, the states delegated certain enumerated powers to the central government. These powers were those that the English political philosopher John Locke termed “federative” and which he defined as “the Power of War and Peace, Leagues and Alliances, and all the Transactions, with all Persons and Communities without the Commonwealth.” These powers had been invested in the imperial government under the colonial system, and, under the articles, the central government was to assume them.

Although in theory, the state governments would not exercise the powers they had vested in the central government, in practice, they retained complete control over the application of these powers. This was a reflection of the fear of central power that to a great extent had inspired the American Revolution. Thus, Congress possessed neither the right to collect taxes nor to raise an army, and it had neither a judiciary nor an executive. Therefore, the central government could declare and conduct war but not create or supply an army; it could borrow money but not provide for its repayment; it could enter into treaties with foreign powers but not prevent violations of international agreements. On paper, its powers were formidable, but in reality, Congress depended completely on the cooperation of the states.

Historians have emphasized the many conflicts during the reform process, first in the Constitutional Convention and later during the ratification struggle. Nevertheless, there was, in fact, a widely shared consensus on the essential features of the reform. Most Americans agreed on the necessity and ends of union; on the propriety of investing federative powers in the central government; and on the need to strengthen Congress. There was relatively little debate on the purposes of the union. Commentators agreed that the central government was intended to manage interstate and international affairs. Congress should provide for the defense against foreign nations; prevent violations of international law and treatises; regulate interstate and international commerce; appoint and receive ambassadors; preserve peace among the states by preventing encroachments on states’ rights; and ensure domestic peace and republican liberty by providing for defense against sedition in the states. The last of these duties has occasionally been interpreted as an undue involvement in the internal affairs of the states in order to quell popular movements. In fact, it originated in the need to maintain stability and republican government in the composite parts in order to guarantee the strength of the Union as a whole. In addition to these duties, some reformers had a more expansive agenda and wanted the central government to take an active role in governing the states. Chief among them was James Madison, who wanted Congress to guarantee “good internal legislation & administration to the particular States.” But this was a minority view that had little influence on the final Constitution.

If there was consensus on the Union’s objectives, there was also agreement that the Articles of Confederation had not met them. Three issues in particular needed to be addressed: Congress had to have the right to regulate trade; it needed a stable and sufficient income; and it had to possess some means by which it could ensure that the states complied with Congress’s requisitions and resolutions.

Economic recovery after the war for independence was hampered by discrimination against American trade. The most serious restrictions were the closing of the Mississippi River and the exclusion of American ships from the British West Indies and British Isles. In order to retaliate against these measures, Congress needed the right to regulate commerce, including the right to tax imports and exports.

The Articles of Confederation had not entrusted Congress with power over taxation. Instead, the central government was expected to requisition money from the states, which would handle the administration of taxation. The system never worked, making it difficult to pursue the Revolutionary War efficiently and provide for the postwar debt. If states neglected or ignored Congress’s legitimate demands, it had no way to enforce compliance. It was therefore necessary to reform the articles so as to provide the central government with power to enforce congressional resolutions.

The framing and adoption of the Constitution had been preceded by several reform initiatives originating in Congress, which sought to correct deficiencies by amending the Articles of Confederation without modifying the organization of the Union. One after another these attempts failed, however, and the reform initiative passed from Congress to the states. In 1785 Virginia negotiated an agreement with Maryland over the navigation of the Chesapeake Bay, and in the following year, Virginia invited all the states to a convention to meet in Annapolis, Maryland, to consider the Union’s commerce. The convention adjourned almost immediately because of insufficient attendance (only five state delegations were present). But the convention also issued a report that spoke of “important defects in the system of the Foederal Government” a political situation that was serious enough “to render the situation of the United States delicate and critical.” The report recommended calling a new convention with a broadened mandate to “take into Consideration the situation of the United States, to devise such further Provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Foederal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union.” Congress and the states agreed to the proposal and a convention was called to meet in Philadelphia on May 14, 1787, “for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation.”

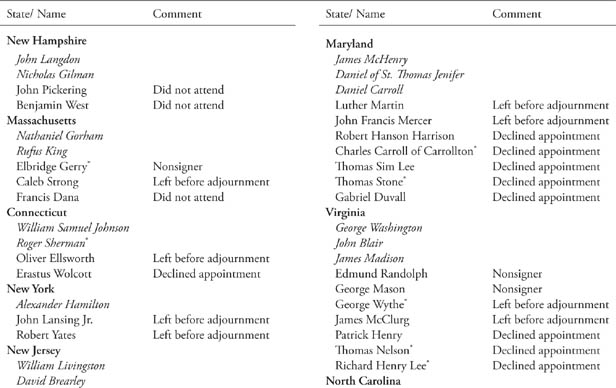

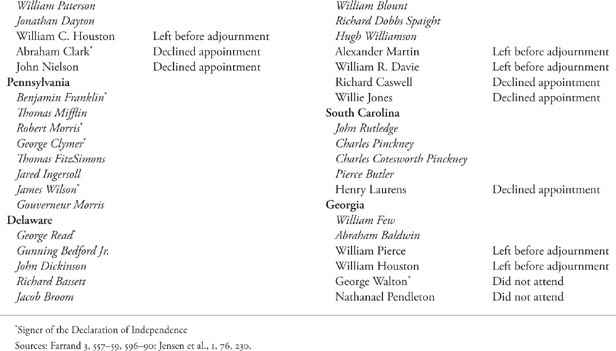

In all, 55 delegates from 12 states attended the Constitutional Convention (only Rhode Island did not send delegates). They belonged to the political leadership of their respective states; many had served in Congress or held a commission in the Continental Army. A majority of delegates were lawyers (34), and almost half were college educated (26). If they were not the assembly of demigods they have sometimes been made out to be, they were nonetheless a group highly qualified to address the ills of the American union.

The convention did not reach a quorum until May 25, 1787, and the delay allowed the Virginia delegation to prepare a set of opening resolutions that set the agenda for the convention. The acceptance of these resolutions on May 30 was the most important decision of the convention, because it superseded its mandate to revise the Articles of Confederation in favor of establishing “a national government . . . consisting of a supreme legislative, judiciary and executive.” The novelty of the Virginia Plan, as the resolutions are known, lay not in an expansion of the powers delegated to the central government but in a reorganization of the structure of the union that would make it possible to use those powers effectively. According to the plan, the projected government would inherit all “the Legislative Rights vested in Congress by the Confederation.” In addition, it would have the right “to legislate in all cases to which the separate States are incompetent, or in which the harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the exercise of individual Legislation”—a broad grant that included both the power to tax and to regulate trade. The plan did not question the aims of the Union, however, stating that like the Articles of Confederation it was created for the “common defence, security of liberty and general welfare” of the member states.

The Virginia Plan was largely the brainchild of James Madison, who came to Philadelphia best prepared of all the delegates. Madison was disappointed with important aspects of the finished Constitution, and his reputation as “Father of the Constitution” rests on his success in determining the basic thrust of the convention’s work by means of the Virginia Plan. Madison had thoroughly analyzed the shortcomings of the Union under the Articles of Confederation and had identified the crucial defect to be the reliance on voluntary compliance of state governments to Congress’s resolutions and the lack of “sanction to the laws, and of coercion in the Government of the Confederacy.” Rather than providing Congress with an instrument of coercion, however, Madison suggested a reorganization of the central government. It would no longer be a confederated government that depended on state governments for both its upkeep and the implementation of its decisions, but a national government legislating for individuals and equipped with an executive and a judiciary to enforce its laws. It was a simple and ingenious solution to a critical problem: how to enable the central government to exercise its powers efficiently.

The basic idea of the Virginia Plan was to create two parallel governments that were each assigned a separate sphere of government business. As was the case under the Articles of Confederation, the business that would fall on the lot of the central government was foreign politics and interstate relations, whereas the state governments would manage their own internal affairs. The two governments would both derive their legitimacy from popular sovereignty and be elected by the people. Each government would be self-sufficient in the sense that it could provide for its own upkeep, legislate on individuals, and have its own governmental institutions for implementing its legislation.

If the line of demarcation that separated the central government from the state governments seemed clear enough in theory, there was a risk that each would encroach on the other. Madison and his supporters in the convention were convinced that the only real risk was state encroachment on the central government, and the Virginia Plan thus provided for its extensive protection. Other delegates were more concerned with the danger of central government encroachment on state interests and rights. In the course of the Constitutional Convention, such critiques of the plan led to important modifications intended to safeguard state interests.

Opposition to the Virginia Plan first came from the delegations of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland, which, at critical points, were joined by Connecticut. During the convention and afterward, these delegations were called “small-state members.” Gradually, concern for the protection of state interests came to be a common concern for almost all the delegates.

At times, objections to the Virginia Plan were so strong that the convention came close to dissolution, and only compromises and concessions saved it. Opposition first arose over the plan’s provision that the “National Legislature” be elected by the people rather than the states and that “the rights of suffrage” in the legislature “ought to be proportioned to the Quotas of contribution [i.e., taxes], or to the number of free inhabitants.” The “small-state” men were not ready to accept this change in the principle of representation but struggled to retain the rule of one state, one vote, as was the case under the Articles of Confederation. Concern for state interests reappeared in demands for protection of specific state rights and disagreement over the mode of electing the president. Conflicts over the status of the states dominated the convention’s business and have tended to overshadow the consensus that existed on the fundamentals of the plan. Thus, the need for stronger central government was not challenged, nor were the concepts of separate spheres of government business and of two self-sufficient governments acting on the same citizens.

The small-state men first offered an alternative plan to that of the Virginia delegation. Presented by William Paterson of New Jersey (on June 14, 1787), the New Jersey Plan agreed to many of the provisions of the Virginia Plan, but left the principle of representation in Congress untouched. Had the plan been accepted, Congress would have continued to be an assembly appointed by and representing states in which each state had one vote. When the convention rejected the New Jersey Plan on June 19, the small-state members fell back on their second line of defense: demand for state appointment to, and state equality in, one of the two branches of the legislature. They secured this goal in the so-called Connecticut Compromise on July 16, whereby the states were to appoint the members of the Senate and have an equal number of representatives in this branch. Senators were to vote as individuals and not as state delegations, however. After this victory, the small-state opposition dissolved.

It was replaced by concern for specific state interests, chiefly emanating from southern delegations. State equality in the Senate meant that the southern states would now be outnumbered eight to five, which made encroachment on southern interests a distinct possibility. Whereas the small-state men had spoken in general and abstract terms of state rights, state interests now took concrete form. As Pierce Butler of South Carolina commented, “The security the Southn. States want is that their negroes may not be taken from them which some gentlemen within or without doors, have a very good mind to do.” Eventually, several demands of the southern states made it into the finished Constitution, among them the Three-Fifths Compromise (which counted three-fifths of the slave population toward representation in the House of Representatives); the prohibition on interference with the slave trade before 1808; the Fugitive Slave Clause (which required that escaped slaves be apprehended also in free states and returned to slavery); and the ban on federal export duties. Concern for state interests also influenced the intricate rules for the election of the president, which were intended to balance the influence of small and large states, both in the North and the South.

Opposition to the Virginia Plan reveals much about conceptions of the Union at the time of its founding. Proposals to create new jurisdictions by means of a subdivision of the states were not seriously considered. Despite their recent and contingent history, the existing states had become political entities whose residents ascribed to them distinct interests arising chiefly from economic and social characteristics. The delegates to the convention further believed that the interests of different states were sometimes conflicting, something that had been repeatedly demonstrated in the 1780s when congressional delegations fought over western lands and commercial treaties. The founders grouped the states into sections of states sharing basic interests, the most important of which were the slave states in the South and the nonslave states in the North. Concern for protection of state interests grew not so much from a fear that the central government would pursue its own agenda to the detriment of the states collectively as from fear that the central government would come under the control of one section that would use it as an instrument to promote its own interests at the expense of another.

State interests were a reality in the minds of the American people and could hardly have been transcended, even if the delegates had wished to do so. Opposition to the Virginia Plan provided a necessary correction to the purely national government first envisioned by Madison. States were now protected from central government encroachment on their interests by state representation in the Senate and by guarantees for specific state interests. The central government was protected from state government encroachment primarily by being made self-sufficient and therefore able to act independently of the states, but also by making the Constitution and federal laws and treatises the supreme law of the land. All state officers and state courts were now bound to obey and uphold the Constitution and federal legislation.

It is often said that the Constitution was the result of a compromise that created a government, in Oliver Ellsworth’s words, “partly national, partly federal.” In comparison to the Virginia Plan, this seems accurate enough. But compared to the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution created a government much more national than federal, able to act in almost complete independence of the state governments. When Madison reflected on the Constitution in The Federalist he remarked, “If the new Constitution be examined with accuracy and candor, it will be found that the change which it proposes, consists much less in the addition of New Powers to the Union, than in the invigoration of its Original Powers.” This is the best way to understand the achievements of the convention. By a radical reorganization of the Union that provided for a separate and self-sufficient central government acting on individuals rather than states, the Constitutional Convention had correctly diagnosed the Union’s fundamental malady and provided for its cure.

The finished Constitution was signed on September 17, 1787, and in a dramatic gesture, three of the delegates—Elbridge Gerry, George Mason, and Edmund Randolph—refused to sign the document. Gerry and Mason feared that the convention had gone too far in creating a strong central government and had failed to safeguard basic civic rights and liberties. Their objections foreshadowed a prominent critique that would soon be directed against ratification of the Constitution.

Framing the Constitution was only the first step toward re-forming the Union. An important part of the reorganization was the establishment of the federal government by an act of popular sovereignty, whereby it would be placed on par with the state governments. It had therefore to be accepted by the people and not the states. To this end, the Constitutional Convention had proposed that the states call ratifying conventions, whose delegates would be chosen by the electorate in each state. Despite some complaint in Congress and some of the states that the convention had exceeded its mandate, ratifying conventions were eventually called in all states except Rhode Island.

The ills arising from the defunct Union had been widely experienced, and the new Constitution stirred enormous interest. Within a few weeks, 61 of the nation’s 80 newspapers had printed the Constitution in full; it also was printed in pamphlets and broadsides. The public debate that followed is impressive in scope, even by modern standards. The Federalists, who supported the Constitution, controlled most of the newspapers and dominated the debate. Yet the opposition, branded Anti-Federalists by their opponents, was nevertheless distinctly heard in both print debate and ratifying conventions.