The attributes treated in the previous chapter stress God’s transcendent otherness from us: hence, the dominance of the negative prefix (e.g., God is infinite, immutable, invisible, etc.). The attributes we consider in this chapter are called “communicable,” because they are predicated of God and creatures, though always analogically.1 Therefore, the way of eminence (via eminentia) takes center stage, with its omni (all) prefixes instead of negations. Especially in light of God’s simplicity, the distinction between incommunicable and communicable attributes is merely a heuristic device. Some theologians treat God’s omniscience and sovereignty under incommunicable attributes, but I am treating these attributes here because they are characteristics of God’s knowledge and power.

Our knowledge is partial, ectypal, composite, and learned, but God’s is complete, archetypal, simple, and innate. Haence, God is omniscient, that is, all-knowing (1Sa 23:10–13; 2Ki 13:19; Ps 139:1–6; Isa 40:12–14; 42:9; Jer 1:4; 38:17–20; Eze 3:6; Mt 11:21). God depends on the world no more for his knowledge than for his being. Nor can his knowledge be any more circumscribed than his presence or duration. Even when we foreknow things hidden from others, our knowledge is finite and fallible. However, God’s foreknowledge is qualitatively distinct. For us, knowing certain things is accidental to our nature; our humanity is not threatened by our ignorance of many things. However, God’s simplicity entails that none of his attributes are added to his existence. It is impossible for God not to know everything comprehensively. Given his eternality, he knows the end from the beginning in one simultaneous act. God knows all things because he has decreed the end from the beginning and “works all things according to the counsel of his will” (Eph 1:11). This knowledge is inseparable from God’s wisdom (Ro 8:28; 11:33; 14:7–8; 1Co 2:7; Eph 1:11–12; 3:10; Col 1:16).

In Scripture, God’s knowledge and wisdom are closely related to veracity or truth (OT: ‘ěmet, ‘ěmûnâ, āmēn; NT: alēthēs, alētheia, alēthinos, pistis). God is truth—in an ethical sense (i.e., fidelity: Nu 23:19; Jn 14:6; Ro 3:4; Heb 6:18) and in a logical sense (i.e., knowing how things really are). These characteristics converge in the prominent biblical theme of God’s faithfulness (Heb. ḥesed), which is defined by his commitment to his covenant. It is this faithfulness that is on trial in covenantal history, involving Israel and Yahweh in the interchanging roles of judge, defendant, and witness—with testimony and countertestimony mediated by the prophets.

God’s simplicity also cautions us against raising God’s omnipotence above his other attributes. God always exercises his power in wisdom, knowledge, and truth. In fact, God is not able to exercise his power in a manner that is inconsistent with any of his other attributes.

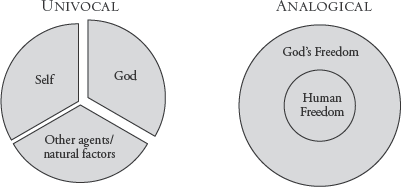

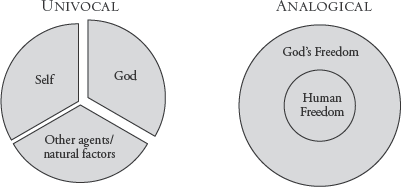

Often, debates over divine and human freedom share a common misunderstanding of agency (willing and acting) as univocal for God and humans. Therefore, the debate turns on who has more power over the other. Although open theism clearly constructs a straw opponent when it accuses Augustinian/Reformed theology of teaching that God is the only cause of all things (omnicausalism), there are extreme examples outside the mainstream that give life to the caricature.2 Hyper-Calvinism shares with Arminianism (and especially open theism) a rationalistic tendency toward a univocal interpretation of the noun “freedom.” The one begins with the central dogma of omnicausalism and the other with the central dogma of libertarian free will. However, if even freedom is predicated of God and humans analogically, then there is not a single “freedom pie” to be rationed (however unequally) between partners.

Human Freedom (ectypal: “In him we live and move and have our being”)

God’s Freedom (archetypal: God is the source of all creaturely freedom)

The reason that creatures possess any power and freedom at all is that they are created in the image of the God, whose sovereignty is qualitatively distinct and unique. Instead of being grateful for this vast creaturely (ectypal) liberty, Satan and human beings since the fall have longed for an independent and autonomous freedom grounded only in themselves. However, this craving to transcend creaturely existence is unreasonable. After all, “The earth is the LORD’S and the fullness thereof” (Ps 24:1). God’s omnipotence, as I. A. Dorner observed, is not set over against our freedom but is its necessary precondition.3 Because God is freedom, such a thing as freedom exists and can be communicated to us in a creaturely mode.

Since all of our knowledge is analogical and accommodated, we can know only that, not how, God’s sovereignty and human responsibility are perfectly consistent. Even when both agents are active in the same event, the terms agents and active are used analogically. Humans do not have less power than God but all of the power that is essential to their created nature. The “freedom pie” is God’s. He does not surrender pieces but gives us our own pie that is a finite analogy of his own. “In him we live and move and have our being” (Ac 17:28). As God’s image bearers, we reflect God’s glory, but God does not give his own glory to a creature (Isa 48:11).

Tyrants stalk the earth devouring the freedom of their subjects. The flame of their power can burn only to the extent that it consumes the liberty of others. However, God “gives … life and breath and everything” to us (Ac 17:25). God is a producer, not a consumer, of our creaturely freedom, and his presence fills our creaturely room with the air of liberty. Precisely because God alone is sovereign, qualitatively distinct in his freedom as Lord, creaturely freedom has its inexhaustible source in abundance rather than lack, generosity rather than a rationing or negotiation of wills.

God knows our thoughts exhaustively (Pss 44:21; 94:11), but God’s thoughts are inaccessible to us apart from revelation. It is not simply that God has more thoughts, better thoughts, or deeper thoughts, but that his way of knowing is his own, never overlapping with creaturely knowledge. “For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, declares the LORD. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts” (Isa 55:8–9). In fact, Paul’s excursus on God’s freedom in election leads to the doxology,

Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!

“For who has known the mind of the Lord,

or who has been his counselor?”

“Or who has given a gift to him

that he might be repaid?”

For from him and through him and to him are all things. To him be glory forever. Amen. (Ro 11:33–36)

In the great courtroom trial of the religions Yahweh declares,

Who is like me? Let them proclaim it,

let them declare and set it forth before me.

Who has announced from of old the things to come?

Let them tell us what is yet to be.

Do not fear, or be afraid;

have I not told you from of old and declared it?

You are my witnesses!

Is there any god besides me?

There is no other rock; I know not one. (Isa 44:7–8 NRSV)

God’s knowledge can no more be confined to a temporal past than his presence can be confined to a spatial place.

God’s knowledge and wisdom are particularly evident in the history of redemption, as the context of Paul’s doxology (Ro 11:33) underscores. God’s wisdom is seen in the revelation of the mystery of Christ in these last days, a wisdom that reduces human speculation and erudition to foolishness (1Co 2:7; Eph 3:10–11; Col 1:16). “In [Christ] we have obtained an inheritance, having been predestined according to the purpose of him who works all things according to the counsel of his will” (Eph 1:11). God’s knowledge and wisdom, then, are not abstract concepts but are displayed characteristically in the service of God’s covenant of grace—that is, in the unfolding mystery of God’s purposes in Christ. It is this wisdom and knowledge that God reveals to his prophets (Isa 42:9; Am 3:7). In fact, Christ is himself the content of that wisdom and knowledge (1Co 1:30). God the Father has no higher or more prized knowledge than his knowledge of the Son—and vice versa.

On one hand, Scripture teaches that God has predestined the free acts of human beings; on the other hand, God represents himself as a genuine partner in history. God’s revealed will is often disobeyed, but his sovereign will (i.e., that which he has predestined) is never thwarted. For example, Jesus proclaimed and offered himself to his people as the Messiah of Israel, even to the point of lamenting, “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it! How often would I have gathered your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you would not!” (Mt 23:37). However, he also said, “No one can come to me unless the Father who sent me draws him” (Jn 6:44), and, “You did not choose me, but I chose you” (Jn 15:16).

In his Pentecost sermon, Peter expresses no fear of contradiction when in the same breath he blames human beings for Christ’s crucifixion and says that Christ was “delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God” (Ac 2:23). God’s predestination in no way rendered the choices and actions of human beings illusory; rather, it was through such uncoerced responses that God fulfilled his secret plan. So God wills and acts, and humans will and act, but “will” and “act” are predicated analogically rather than univocally. In the familiar Joseph narrative, the same event—Joseph’s cruel treatment by his brothers—has two authors with two distinct intentions: “You meant evil against me, but God meant it for good” (Ge 50:20).

Even in his revelation God remains transcendent and incomprehensible. God invites the whole world to salvation in his Son, yet effectually calls and gives faith to all whom he has elected from all of eternity. Our province is not God’s secret counsels, but his revelation: “The secret things belong to the LORD our God, but the things that are revealed belong to us and to our children forever” (Dt 29:29). While God’s secret plan does not change, his revealed plans often do. It is good news for us that the former is the basis for God’s immutable commitment to our salvation, regardless of the obstacles we place in his path. God knows all things exhaustively because he has decreed all things exhaustively.

Open theists have recognized that even the traditional Arminian argument for predestination based on God’s infallible foreknowledge renders those foreknown choices and actions certain. Therefore, open theists deny such exhaustive divine foreknowledge: God knows everything that he can know, but this excludes the free decisions of human beings.4

Wolfhart Pannenberg draws together omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence, and he makes a good case for this. “No power, however, great, can be efficacious unless present to its object,” he observes. “Omnipresence is thus a condition of omnipotence. But omnipotence shows what omnipresence by the Spirit actually means.”5 Pannenberg is not suggesting that only the Spirit possesses the divine attribute of omnipresence, but he underscores the important point that the Godhead exercises this omnipresence from the Father, in the Son, and by the Spirit. Essences do not will and act; only persons do. Because God is a Trinity, he acts sovereignly not only on creation but in it and within it, winning its consent rather than coercing or directly causing every decision and action. A Trinitarian perspective on God’s sovereignty guards against Aristotle’s mechanical concept of the Unmoved Mover.

John of Damascus seems to be thinking along similar lines when he relates God’s omnipotence to his omniscience and omnipresence. First, he affirms that God knows all things, “holding them timelessly in his thoughts; and each one conformably to his voluntary and timeless thought, which constitutes predetermination and image and pattern, comes into existence at the predetermined time.”6 And then he adds, “For he is his own place filling all things and being above all things, and himself maintaining all things. Yet we speak of God having place and the place of God where his energy becomes manifest…. And his sacred flesh has been named the foot of God. The church, too, is spoken of as the place of God: for we have set this apart for the glorifying of God as a sort of consecrated place wherein we also hold converse with him.”7

Therefore, a biblical view of God’s sovereignty must always bear in mind the following correlatives. First, only when we recognize that God is qualitatively distinct from creation can we see that God is free to be the creator and redeemer, while we are free to be creatures and the redeemed. As Paul’s citation of the Greek poet affirms, we live and move and have our being in God (analogically), not with or alongside God (univocally). It is not shared space but a lush garden of our own creaturely freedom that God has given to us.

Second, only when we understand God’s sovereignty in the light of his simplicity—that is, the consistency of his willing and acting in accordance with his other attributes—can we avoid the notion of a divine despot whose sovereignty is unconditioned by his own nature. The idea of God’s “absolute might” advocated by late-medieval voluntarism was judged by Calvin to be “profane.” “We fancy no lawless god who is a law unto himself.”8

Third, we must always bear in mind that in every exercise of his will and power, God is not a solitary monad but the Father, the Son, and the Spirit. The Father always wills and acts in the Son and by his Spirit, as well as through contingent agency. Therefore, God’s sovereignty cannot be conceived as brute force or control.9

God’s knowledge, wisdom, and power are insepaarable from his goodness. In fact, in the strict sense, Jesus said, “No one is good except God alone” (Mk 10:18). God’s infinite goodness is the source of all creaturely imitations. Precisely because God does not depend on the world, his goodness is never threatened. God is good toward all he has made, even his enemies (Ps 145:9, 15–16; Mt 5:45). He can afford to be, because he is God with or without them.

Because God’s attributes are identical with his essence, God not only loves; he is love (1Jn 3:1; 4:8, 16).10 God loves absolutely and without any compulsion from the object of his love (Mt 5:44–45; Jn 3:16; 16:27; Ro 5:8). God takes delight in that which he does not need but nevertheless desires. Here, too, we must see that human love is not the measure of divine love, but vice versa. God is the original; we are the copy: “In this is love, not that we have loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the propitiation for our sins” (1Jn 4:10).

Only God can love in absolute freedom, desiring the other without needing the other. It is not only impossible but is a cruel demand to expect human beings to love each other out of pure, disinterested benevolence. Even apart from sin, human beings were created in a web of relationships not only with each other but with nonhuman creation. When these relationships are functioning properly, each has what he or she needs and loves out of gratitude and mutual dependence as well as simple desire for the other. However, God loves in perfect freedom. Therefore, he loves even those who do not return his love, and he loved us eternally even while we were enemies (Ro 5:10).

In the light of God’s simplicity, we can never pit God’s sovereignty against his love or his love against his sovereignty. It is especially in our day not a far stretch from “God is love” to “Love is God.” However, as C. S. Lewis observed, when love itself becomes a god, it becomes demonic.11 God always exercises his power, holiness, righteousness, and wrath—as well as his love and mercy—in conformity with his goodness. In fact, we could hardly affirm God’s goodness if he did not uphold justice and the cause of his righteousness against sin and evil.

God’s goodness is evident in creation and providence, of course, but the clearest evidence of the complete consistency between God’s goodness and his sovereignty, justice, wrath, and righteousness is Christ’s cross. There we behold the face of the God-Man who cries out, “It is finished.” There, with unparalleled clarity, we see how far God is willing to go in order to uphold all of his attributes in the simplicity of his being. Human love is analogical of God’s love, not vice versa. David Tracy reminds us that we must begin with the particular act of God in Jesus Christ rather than a “general conception” of love.

[I]f this classic Johannine metaphor “God is love” is not grounded and thereby interpreted by means of the harsh and demanding reality of the message and ministry, the cross and resurrection of this unsubstitutable Jesus who, as the Christ, disclosed God’s face turned to us as Love, then Christians may be tempted to sentimentalize the metaphor by reversing it into “Love is God.” But this great reversal, on inner-Christian terms, is hermeneutically impossible. “God is love": this identity of God the Christian experiences in and through the history of God’s actions and self-disclosure as the God who is Love in Jesus Christ, the parable and face of God.12

If God’s love could trump his other moral attributes, then the cross represents the cruelest waste. The cross is the clearest testimony to God’s simplicity—that is, his undivided and indivisible character.13

What makes God’s love so comforting, therefore, is not only the obvious point that it has not been twisted into lust (which idolizes the other only to consume and dismember it as an object) but the more basic fact that this is so precisely because God’s love is unconditioned by anything in the creature. Whenever God acts toward creatures, it is out of the complete satisfaction that he already enjoys as the Trinity. The eternally begotten Son lives from the love of the Father, but the Father is such because he has a Son, and in the Spirit the Father and the Son not only have a third person to love but one who loves them in return and brings sinful creatures into the circle of that loving fellowship. As Wolfhart Pannenberg observes, the Augustinian conviction that “God is he who eternally loves himself” can be maintained only when we understand this not only as the love of a solitary person for his own essence but as the love of the divine persons for each other.14 In this eternal intratrinitarian exchange, no one is ever let down. There is no Stoic fear of entrusting one’s happiness to the other.

Necessary rather than contingent, God’s essential attributes would be expressed and manifested even if there were no fall into sin or even a creation external to the triune God. God would still be gracious and merciful in his essence even if there were no transgressors. In fact, God’s gracious and merciful character does not require that he show mercy to anyone. Rebellion of such a high creature against such a holy God deserves everlasting punishment. God remains gracious and merciful in his essence, even though the exercise and objects of his mercy are determined in absolute freedom. In other words, God is not free to decide whether he will be merciful and gracious, but he is free to decide whether he will have mercy on some rather than others: “I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion” (Ro 9:15, appealing to Ex 33:19). By definition, grace is undeserved, and mercy is the opposite of one’s deserts.

Appealing to Reformed orthodoxy, Barth underscored the danger in treating grace merely as a gift, especially (as in Roman Catholic teaching) as an infused substance, abstracted from God in Christ. In grace, God gives nothing less than himself. Grace, then, is not a third thing or substance mediating between God and sinners, but is Jesus Christ in redeeming action. “God owes nothing to any counterpart.” In short, “Grace means redemption,” Barth adds.15 Beyond the love and goodness that God shows to creation generally, grace “is always God’s turning to those who not only do not deserve this favour, but have deserved the very opposite.”16 In fact, “Grace itself is mercy.”17

The confidence of those who trust in God’s promise is that “God is gracious and full of compassion” (Pss 86:15; 103:8; 116:5; 145:8). B. A. Gerrish points out that especially in Paul’s eschatological thinking, “God’s grace has appeared … ‘Grace,’ for [Paul], means more than a divine attribute: it refers to something that has happened, entered into history,” as in John 1:17: “Grace and truth came (egeneto) through Jesus Christ” (cf. 2Ti 1:9–10).18 Grace is God’s free favor toward sinners on account of Christ.

Similar to grace and mercy is God’s patience toward transgressors (Ex 34:6; Ps 86:15; Ro 2:4; 9:22; 1Pe 3:20; 2Pe 3:15). Here, too, God is patient, but he is free to show his patience to whomever he chooses. Patience presupposes a situation in which God could justly respond in wrath. Grace, mercy, and long-suffering are the form that God’s love and goodness take in relation to sinners.

At the same time that God is kind, merciful, and long-suffering, he is also holy. The Hebrew word for “holy” (qôdeš) comes from the verb “to cut or separate,” translated into Greek as hagios from the verb “to make holy” (hagiazō). In general terms, it underscores the Creator-creature distinction. God is majestic, glorious, beyond reproach. In a certain sense, holiness characterizes all of God’s attributes. In his communicable and incommunicable attributes, God is qualitatively distinct from us. Beyond this ontological distinction, however, holiness typically refers in Scripture to God’s ethical purity, which is especially evident against the backdrop of human sinfulness. God cannot be tempted nor tempt; he is ethically incapable of being drawn into evil (Jas 1:13). Thus, God’s holiness especially marks the ontological distinction between Creator and creatures as well as the ethical opposition between God and sinners. However, because of God’s mercy, God’s holiness not only highlights his difference from us; it also includes his movement toward us, binding us to him in covenant love. In this way, God makes us holy. That holiness which is inherent in God alone comes to characterize a relationship in which creatures are separated unto God, from sin and death. Only in Christ can God’s holiness be for us a source of delight rather than of fear of judgment.

Simply by creating the world in a state of rectitude as the space for fellowship with creatures, God hallowed the world. Yet after the fall, the holy becomes profane, subject to the curse. Nevertheless, God claims for himself certain places, peoples, and times as the sphere within which he will work out his redemptive purposes and even show his common grace to secular culture. When God elects Israel, calling Abram out of Ur, he makes holy that which is common, literally cutting Israel out of the nations by circumcision. While the nations inhabit an enchanted cosmos filled with gods and supernatural forces, Israel knows only Yahweh and its own election by Yahweh. Barth rightly comments, “The holy God of Scripture is certainly not ‘the holy’ of R. Otto, a numinous element which, in its aspect as tremendum, is in itself and as such divine. But the holy God of Scripture is the Holy One of Israel.”19

The close proximity of God’s holiness and glory (kābôd) is especially evident in Isaiah’s vision (Isa 6), and both concepts are closely related to the Spirit as God’s Shekinah presence among his people and, one day, throughout the earth. This holiness must be read by us through the lens of the gospel; otherwise, it becomes a blinding glory, an overwhelming presence that reduces sinful creatures to death, or to an idolatrous mysticism—a theology of glory. Only in Christ are the unholy made holy, elected, and separated out of the world as the temple that his glory fills.

The New Testament in no way contradicts this distinction between holy and profane, but rather God’s holiness widens to include Gentiles, who are “cut out” of the perishing world through faith and receive the covenant sign and seal of baptism (Ac 10:9–48). Thus, as we have seen with other attributes typically associated with God’s transcendence, God’s holiness is a marker not only of God’s distinction from the creation but also of God’s driving passion to make the whole earth his holy dwelling. Although God alone is essentially holy, he does not keep holiness to himself but spreads his fragrance throughout creation. God is holy in his essence; people, places, and things are made holy by God’s energies.

Righteousness (from the root sdq) in the Old Testament is a simultaneously forensic and relational term. It is a “right relationship” that is legally verified by obedience to the covenantal stipulations.20 It is related closely to mišpat (justice).21 God’s righteousness is also connected with his mercy, especially in the Psalms. “The maintenance of the fellowship now becomes the justification of the ungodly. No manner of human effort, but only that righteousness which is the gift of God, can lead to that conduct which is truly in keeping with the covenant.”22 God has a moral vision for his creation, which is revealed in the various covenants that he makes with human beings in history, and his righteousness involves his indefatigable determination to see that vision through to the end for his glory and the good of creation.

At the same time, God’s righteousness cannot simply be collapsed into his mercy (i.e., justification by grace through faith). As the revelation of God’s moral will (i.e., law), God’s righteousness condemns all people as transgressors; as the revelation of God’s saving will (i.e., the gospel), God’s righteousness saves all who believe (Ro 3:19–26). In both cases, God upholds his own righteousness. Against Albrecht Ritschl’s view, which collapses righteousness into mercy, Barth affirms that God’s righteousness includes the concept of distributive justice—“a righteousness which judges and therefore both exculpates and condemns, rewards and also punishes.”23 Yet for Barth, this condemnation turns out to be just another form of love and grace. According to Barth, God’s wrath is always a form of mercy.24 However, in Scripture, God’s wrath is his righteous response to sin and his mercy is a free decicion to grant absolution to the guilty. As we have seen, God is free to show mercy on whomever he will and to leave the rest under his just condemnation. The righteousness that God discloses in the law brings condemnation, but the gift of righteousness that God gives brings justification and life (Ro 3:19–22). Once again, it is at the cross where we see the marvelous unity of divine attributes that might seem otherwise to clash. This paradox is lost if mercy, righteousness, and wrath are synonymous terms.

Like mercy, grace, and patience, jealousy and wrath are aroused only in the context of an offense. God does not need to display these attributes in order to be who he is, but they are the response we would expect from the kind of God who is good, just, and holy. Just as God “has mercy on whomever he wills,” he also “hardens whomever he wills” (Ro 9:18). God must be just, but he is free to display his mercy toward some and his wrath toward others (v. 22). Even when God expresses his wrath, it is not the ill-tempered and irrational violence that is associated with the eruption of human emotion. God’s wrath always expresses his wisdom and judgment—and even his love, which along with his other attributes has been accosted by those whom he created for love and to love. A being who is perfect in goodness and love must exercise wrath against sin, evil, hatred, and injustice.

Especially when considering God’s jealousy, the doctrine of analogy proves its merits. We can be glad that whatever it is like for God to be jealous, it is qualitatively different from human jealousy—especially in our sinful condition. For example, as I. A. Dorner remarks, “The divine jealousy is one that is holy and not one that is envious.”25 Because God is righteous, holy, and just, and not a Stoic sage whose bliss is unaffected by evil actions, “his wrath is quickly kindled” (Ps 2:12). As waith wrath, jealousy strikes most of us as unworthy of God particularly because of its associations in our own experience. As wrath generally connotes a thirst for revenge or brings to mind the temper tantrums of the powerful against the weak, jealousy is with good reason regarded universally as a negative human trait. But instead of jettisoning jealousy or attempting to “translate” it into (i.e., accommodate it to) our own experience, the biblical representation of God’s jealousy can open us up to a new understanding of the term that challenges and potentially heals our experiences of corrupt human jealousy.

Robert Jenson is probably not saying too much when he suggests, “In the Scriptures … it is first among the Lord’s attributes that he is ‘a jealous God.’”26 Yet once again this claim must be situated in its covenantal context. In the ancient Near Eastern treaties, the suzerain (great king) who liberated a lesser nation required the vassal to serve him only, refusing any backroom alliances with other suzerains. Jealousy, then, was the appropriate response of the suzerain to the treasonous conspiracy of the servant with his enemies. However, even this suzerain-vassal relationship is an analogy, and in Yahweh’s unique performance the role of “jealous suzerain” is transformed.

The sole lordship of Yahweh, as we have seen, is the presupposition of biblical faith, and it is carried forward into the fuller revelation of God’s identity as applied to Jesus Christ: “I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me” (Jn 14:6). “Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” (Php 2:9–11). Therefore, “There is salvation in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given among mortals by which we must be saved” (Ac 4:12 NRSV). God will not give his glory to another (Isa 42:8). God is jealous for his own name and for the people who call on his name and are called by his name.

Jealousy in humans is a perversion because it implies a right that does not belong to us. We hoard possessions, and to the extent that even relationships, creatures, and other people can become possessions rather than genuine others, our jealousy confirms our oppressive stance. However, the God who possesses creation already exercises his covenant lordship by giving rather than possessing, by sacrificing rather than hoarding, by spending rather than saving his wealth. It is God’s jealousy for his people, in fact, that underscores his love and eventuates in their salvation. In us, jealousy is a form of coveting—claiming that which is not ours. In God, jealousy is a form of protecting—guarding that which is precious to God, both his character and his covenant people.

1. Turretin, Elenctic Theology, offers a typical scholastic definition: “The communicable attributes are not predicated of God and creatures univocally because there is not the same relation as in things simply univocal agreeing in name and definition. Nor are they predicated equivocally because there is not a totally diverse relation, as in things merely equivocal agreeing only in name. They are predicated analogically, by analogy both of similitude and of attribution…. Believers are said to be partakers of the divine nature (2Pe 1:4) not univocally (by a formal participation of the divine essence), but only analogically (by the benefit of regeneration … since they are renewed after the image of their Creator, Col 3:10)” (1:190).

2. Against such extremes (and caricatures), the consistent teaching of Reformed theologians has affirmed God’s sovereign decree concerning “whatsoever comes to pass,” yet without coercion or directly causing every event (Westminster Confession, 3.1).

3. I. A. Dorner, Divine Immutability: A Critical Reconsideration (ed. Robert R. Williams and Claude Welch; Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994), 147.

4. See, for example, Clark Pinnock, “Systematic Theology,” in The Openness of God: A Biblical Challenge to the Traditional Understanding of God (ed. Clark Pinnock et al.; Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1994), 121-23; Clark Pinnock, Most Moved Mover (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2001), 100; William Hasker, “An Adequate God,” in Searchingfor an Adequate God: A Dialogue between Process and Free Will Theists (ed. John B. Cobb Jr. and Clark H. Pinnock; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), 218-19. These writers insist that this view still affirms God’s omniscience, but they fail to demonstrate how “allknowledge” can exist when God is said to be ignorant of the vast majority of future actions (namely, those brought about by human decision).

5. Wolfhart Pannenberg, Systematic Theology (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1991), 1:415.

6. John of Damascus, “An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith,” in NPNF2, 9:12 (PG 94, col. 837).

7. Ibid., 9:15 (PG 94, col. 852). The same point was made in Paul’s speech—namely, that it is precisely because God transcends time and space that he can give all places and times to creatures (Ac 17:24–27).

8. Calvin, Institutes 3.23.2. In his Sermons on Job (trans. Arthur Golding; Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1993), Calvin writes, “And undoubtedly whereas the doctors of the Sorbonne say that God hath an absolute or lawless power, it is a devilish blasphemy forged in hell, for it ought not once to enter into a faithful man’s head” (415).

9. As Stephen N. Williams observes in an essay (“The Sovereignty of God,” in Engaging the Doctrine of God [ed. Bruce L. McCormack; Grand Rapids: Baker, 2008], 175–78), this is a weakness in some defenses of God’s sovereignty.

10. For an excellent biblical-theological treatment of this attribute, see especially D. A. Carson, The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God (Wheaton: Crossway Books, 1999).

11. C. S. Lewis, The Four Loves (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1960), 22.

12. David Tracy, “Trinitarian Speculation and the Forms of Divine Disclosure,” in The Trinity (ed. Stephen T. Davis, Daniel Kendall, SJ, Gerald O’Collins, SJ; Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1999), 285-86. In a similar vein, J. Gresham Machen wrote, “It is a strange thing when men talk about the love of God, they show by every word that they utter that they have no conception at all of the depths of God’s love. If you want to find an instance of true gratitude for the infinite grace of God, do not go to those who think of God’s love as something that costs nothing, but go rather to those who in agony of soul have faced the awful fact of the guilt of sin, and then have come to know with a trembling wonder that the miracle of all miracles has been accomplished, and that the eternal Son has died in their stead” (Selected Shorter Writings [ed. D. G. Hart; Phillipsburg, N.J.: P&R, 2004], 32).

13. One of many examples of attempting to decode the inner being of God (including the Trinity) by making God’s love alone definitive of his inner being is Stanley Grenz, Theology for the Community of God (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), 72–75. First, this move renders God’s wrath merely a subjective experience of unbelievers rather than an objective divine stance (73), which eliminates any concept of propitiation. Second, this leads Grenz to assert that the essential unity of the Trinity is simply the love of each member for each other, since love “builds the unity of God” (72; cf. The Named God and the Question of Being: A Trinitarian Theo-Ontology [Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2005], 336). This intratrinitanan love “describes God’s inner life…” and offers “a direct insight” into his being (The Named God, 339). As a consequence of this elimination of the Creator-creature distinction, Grenz adds, “The Bible is the outworking of God’s essence through the story of God’s activity in history in bringing about salvation” (397, emphasis added). Impatience with mystery and analogy seems to motivate these and similar attempts to unmask the hidden God. A different, but no less hazardous, speculation about the Trinity based on love may be found in Jonathan Edwards. See Oliver D. Crisp, “Jonathan Edwards’ God: Trinity, Individuation, and Divine Simplicity,” in Engaging the Doctrine of God: Contemporary Protestant Perspectives (ed. Bruce L. McCormack; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), 91–105.

14. Pannenberg (Systematic Theology, 1:426) corrects Eberhard Jüngel on this point, citing Jüngel’s God as the Mystery of the World (trans. Darrell L. Guder; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1983).

15. Barth, Church Dogmatics, vol. 2, pt. 1, 353-55. Barth quotes Polanus as follows: “Gratia in Deo residens est essentialis proprietas eius nimirum benignissima voluntas Dei et favor, perquem vere et proprie est gratiosus, quo favet et gratis benefacit creaturae suae” (353).

16. Ibid., 356.

17. Ibid., 369.

18. B. A. Gerrish, “Sovereign Grace: Is Reformed Theology Obsolete?” Interpretation 57, no. 1 (January 2003): 45.

19. Barth, Church Dogmatics, vol. 2, pt. 1, 360.

20. Righteousness has been one of the most widely debated terms in the Old Testament. Walther Eichrodt noted, “It is a decided obstacle to any attempt to define the concept of divine righteousness, that the original significance of the root sdq should be irretrievably lost.” The predominant use is right behavior. “When applied to the conduct of God, the concept is narrowed and almost exclusively employed in a forensic sense. God’s sedāqā or sedeq is his keeping of the law in accordance with the terms of the covenant” (Theology of the Old Testament [trans. J. A. Baker; Philadelphia: Westminster, 1961], 1:240). This is not the distributive justice of Roman law, though, which is too formal and abstract to describe Israel’s thought. Eichrodt follows the lead of Hermann Cremer, who interpreted righteousness as a right relationship between persons.

21. Ibid., 1:241.

22. Ibid., 1:247.

23. Barth, Church Dogmatics, vol. 2, pt. 1, 391.

24. According to Barth’s notion of universal election, every person is simultaneously condemned in himself or herself and justified in Christ. There can be no Easter Yes without the Good Friday No, but it is the Yes that wins out in the end, not only for all who believe but, at least in principle, for every person (ibid., 394). Thus, condemnation and justification apply to all people, not to a race divided between righteous/unrighteous, sheep/goats, saved/lost, justified/condemned, etc. In the contexts in which these contrasts appear in Scripture, however, there is no hint of these categories simply reflecting the dialectical truth about every person.

25. Dorner, Divine Immutability, 178.

26. Robert Jenson, Systematic Theology (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1997), 1:47, referring to Exodus 34:14.