Chapter Ten

Goblin wars

Mentions of Gondolin in The Hobbit

IT IS WORTH remembering that Gondolin is one of the more obvious of a number of allusions to The Silmarillion that Tolkien allowed to slip, mostly unnoticed, into his novel The Hobbit. During their ‘Short Rest’, in the chapter of that name, Elrond one day examines the swords the dwarves had taken from the troll-hoard, and he identifies them immediately, and with good reason, as it turns out. They are swords made in Gondolin for the Goblin wars many ages before. Thorin’s new sword is called Orcrist, or Goblin-cleaver, while Gandalf ’s is the sword Glamdring, meaning ‘Foe-hammer’, which was once worn by Turgon the king of Gondolin. Turgon, who fell with the city, was Elrond’s great-grandfather, and Elrond is in fact Elrond Half-Elven, one of the wielders of a ring of power. His father is Eärendel, son of Tuor, who married Idril of Gondolin, the daughter of Turgon. A key figure in the mythology, Elrond reveals his long life and ancestry in LOTR to the great amazement of the hobbits. But here in The Hobbit his identity is played down, although he does admit that the High Elves of Gondolin are his kin.

In the original draft of The Hobbit, Tolkien had not fully decided that this Elrond was in fact the same as the Elrond of the mythology. He is described as an elf-friend, ‘kind as Christmas’, an attractive alliterating phrase that was later changed to ‘kind as summer’ to remove the overt Christian reference. And the passage where Elrond identifies the swords is considerably shorter; he knows them to be old swords, made in Gondolin for the Goblin wars, and he wonders whether they came to the trolls from a dragon’s hoard, perhaps from one of the dragons that plundered the city at its fall.1 At this point in the writing of The Hobbit the High Elves are still referred to as gnomes, and the two swords do not as yet have special names that can be identified with their previous owners (Tolkien actually names the swords in a later passage in this draft version). And at this stage in the conception of the character of Elrond, there is no assertion at all that he might be related to these people from ages past.

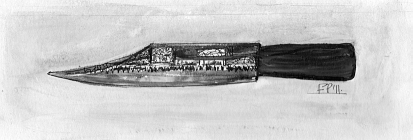

Fig. 10a Short sword or seax

Fig. 10b Long sword

In the published version, there is a much longer discussion of the origin of the swords. Thorin looks at his sword with a new interest and he asks Elrond how the swords came into possession of the trolls. Elrond is uncertain, but he hazards a guess that the trolls plundered from earlier plunderers or perhaps came upon forgotten treasure abandoned in the caverns of the mines of Moria since the dwarf and goblin war. Elrond’s words cause Thorin to ponder and he vows to keep the sword in honour until a time when he may use it, a wish that Elrond feels will soon be granted when the expedition proceeds onward to the mountains. The mention of Moria is a reference forward to LOTR, when Gandalf and his company are again compelled to give up an ascent of the mountains and try their luck passing through the tunnels under the mountain. In all this discussion goblins figure chiefly as the collective enemy, and the passage neatly anticipates the events of the coming chapter.

The nature of goblins

As we discussed above, The Hobbit gives a vivid account of the ‘over hill’ journey of the hobbit and the dwarves, of the rock-falls and storms and wind and rain, as well as the grandeur – if not overwhelming grandeur – of the mountain country through which they must pass. Similarities were also noted with the story of Tuor’s ‘under hill’ journey to Gondolin, when he travels with his companion Voronwë through the rocky underground passages which, despite their fear of ‘Melko’s goblins, the Orcs of the hills’, lead them safely to the gateway of Gondolin itself (see p. 136 above). In chapter 4 of The Hobbit this pattern of ‘Over Hill and Under Hill’ is repeated when the harsh weather forces the company of travellers to take refuge in a cave which Fili and Kili find round the next corner of the winding mountain path. Here the fear of the orcs would be justified, but none seems to feel it save perhaps Gandalf and Bilbo. It is Gandalf who asks whether they have thoroughly explored this cave, and it is Bilbo who has trouble sleeping and when he does finally sleep has dreams filled with nightmarish fears. Certainly the ever-present narrator shares their fears, for he comments to his young readers on the dangerous nature of caves, the fact that ‘you don’t know how far they go back, sometimes, or where a passage behind may lead to, or what is waiting for you inside’.

The narrator’s hint is enough for most to guess what sort of thing will happen next. The cave becomes a deceptive refuge, a place to talk and forget the storm, to send smoke-rings dancing up by the roof, a place to make plans, a place to sleep. The narrator’s hint now becomes a warning, for this (so he says) is the last time they will use their ponies and all their other gear on the journey. Bilbo wakes up just in time to shout a warning to Gandalf as all their ponies and baggage disappear through a sudden gap at the end of the cave. The narrator’s hints and warnings have all led up to this moment, which he relishes in a sentence with a characteristic phrasal verb ‘Out jumped the goblins’, several repetitions of the subject, and a whole set of suitable qualifiers of size, manner and quantity:

Out jumped the goblins, big goblins, great ugly-looking goblins, lots of goblins, before you could say rocks and blocks.

The ‘out jumped’ construction might be compared with the phrase ‘up jumped Bilbo’ used twice of the protagonist when he oversleeps and hurries out of bed for a late breakfast (it is the opening phrase of chapter 2, repeated again when Bilbo sleeps long and deep in Beorn’s great hall in chapter 7). There is a kind of robust jolliness to this account (despite the potential seriousness of the theme) which suits Tolkien’s purpose – at least in this part of the novel – to imitate the oral style of a narrator telling a comic tale to a listening audience of children. Echoing the ‘rocks and blocks’ tag, the narrator then says that the goblins immediately snatched and grabbed all the sleeping travellers and carried them through the crack ‘before you could say tinder and flint’. The rhyming proverbs only add to the humorous effect, and of course when the goblins pinch Bilbo roughly as they carry him away he once again wishes he was back home safely in his nice bright bachelor den. The humour continues as the goblins whisk him down underground passages deep and dark; for though their dark depths compare well for their fearfulness to those through which Tuor and Voronwe pass in The Fall of Gondolin, here the goblins run through them precipitously since they know the way ‘as well as you do to the nearest post-office’.

Two opposing traditions about goblins as creatures of folklore and folk-belief collide here: on the one hand goblins are mischievous; on the other hand they are evil. However, the first time Tolkien ever used the word goblin back in 1915 in his published poem ‘Goblin Feet’, it referred probably to small sprites or brownies and had no evil connotations whatsoever; nor did the creatures observed in the poem appear even mischievous. But this was soon to change, and Tolkien came to regret ever having published that particular poem. In The Book of Lost Tales the word orc is the preferred designation for the same kind of creature, but in 1932 he went back to the word goblin for his children’s stories in The Father Christmas Letters,2 and retained the word when he wrote The Hobbit. The OED provides a working definition for goblin as ‘a mischievous ugly demon’ and traces the word itself back to Middle English gobelin, also spelt gobolyn, gobelyn, a loan from Anglo-French gobelin, which derives it in turn from medieval Latin gobelinus. The word is related to the rare English word kobold (derived from German), ‘a familiar spirit, brownie, or underground spirit in mines etc.’; the name of the metal cobalt derives from the same source. The notion of ‘mischievous’ seems relevant here, as is the German connection, for one of the sources of the idea must be German folk-tales of the kind collected by the brothers Grimm in their Household Tales. A well-known example would be the mischievous ugly little man in the story Rumpelstiltskin.3 Another would be the story The Prince Afraid of Nothing about a king’s son who has to free a castle and a princess from enchantment by spending three nights in the great hall, enduring the torments of little devils but without being afraid or making a sound. In the German text the little devils are called Teufel or Teufelspuk (i.e. ‘devils’), but at one point in Margaret Hunt’s 1884 translation of the Household Tales they are hobgoblins:

Fig. 10c Goblin with sword

The hob-goblins came again: ‘Art thou there still?’ cried they, ‘thou shalt be tormented till thy breath stops.’ They pricked him and beat him, and threw him here and there, and pulled him by the arms and legs as if they wanted to tear him to pieces, but he bore everything, and never uttered a cry. At last the devils vanished, but he lay fainting there, and did not stir, nor could he raise his eyes to look at the maiden who came in, and sprinkled and bathed him with the water of life. But suddenly he was freed from all pain, and felt fresh and healthy as if he had awakened from sleep, and when he opened his eyes he saw the maiden standing by him, snow-white, and fair as day.4

Are these really devils, or are they in fact goblins under another name, creatures of German folklore rather than the fallen angels of Christian theology? Certainly the pricking and beating are reminiscent of how the goblins behave in The Hobbit.

A Victorian novelist well acquainted with the German folklore tradition was George MacDonald, a favourite writer of Tolkien’s Oxford friend and colleague C.S. Lewis. MacDonald’s The Princess and the Goblin was an overt influence on both Lewis’s Narnia and Tolkien’s Misty Mountains. This children’s novel tells of an eight-year-old princess living somewhere in mountainous central Europe, whose father has confined her indoors in their castle, under the constant supervision of a nurse, because of the threat of kidnapping by the goblins – otherwise known as gnomes or kobolds – who haunt the mineworkings in the surrounding countryside. MacDonald’s goblins are small, misshapen creatures apparently descended from a race of people banished for their misdemeanours, who then retreated into the underground caves and tunnels of the mountain, where they plot their mischief and revenge on the people ‘upstairs’. Rather like Gollum in The Hobbit they hate the sunlight, though they do use torches, and like hobbits they walk barefoot – this is what the miner’s son Curdie discovers is their weakness, for though their heads are hard, their feet are soft. They are ruled by a king, like the Great Goblin in The Hobbit; this king also holds court in a large cavernous hall beneath the mountain. And although they plot to destroy the miners, the goblins are nevertheless figures of fun, easily outwitted by stamping on their feet or chanting verses at them, which is painful to their ears. The mischievous snatch-and-grab goblins of the early chapters of The Hobbit are clearly of a similar kind to those of MacDonald,5 and they do not, at least at first, seem quite as dangerous and malicious as they perhaps should.

In English in particular, as well as meaning mischievous sprite, goblin and the related hobgoblin refer also to the demons of Christian theology, as in the line from Bunyan’s hymn ‘Hobgoblin nor foul fiend shall daunt his spirit’. One of the earliest citations offered by the OED for goblin is from the late fourteenth-century Wyclif Bible translation: ‘Of an arowe fliynge in the dai, of a gobelyn goynge in derknessis’ (Psalm 90:6). The idea of a goblin walking in the darkness is of course highly relevant to the present context, but what is noteworthy of course is that the mischievous element of the German mountain sprite is lacking here. This demonic, wholly evil sense of goblin is in the end the one most relevant to Tolkien’s purpose: the goblins are Melko’s orcs, the perversions of nature brought into being by this Satanic figure of the mythology. As three present-day editors of the OED point out in their study of Tolkien’s vocabulary, it is likely that the mischievous folktale associations of the word goblin caused Tolkien to replace it with orc as the usual term for such creatures in LOTR.6 Similarly, he tended to remove such words as gnome and fairy in his later writings, and replace dwarfs and elfin with dwarves and elvish for the simple reason that the earlier words had the wrong feel: they were too frivolous and had the wrong associations in the minds of most readers. Incidentally, it has been shown that the word orc most likely derives from orcneas, a word for ‘demons’ that occurs appropriately in Beowulf. Again Tolkien took care in a prefatory note in The Hobbit to point out that orc means goblin or hobgoblin and is not the English word applied to ‘sea-animals of dolphin-kind’.

In the period between The Hobbit (1937) and LOTR (1954–5), not only did the word for this evil creature change but also its presentation in Tolkien’s fiction. It is appropriate to consider, for a contrast with the cave episode from The Hobbit, other scenes involving goblins or orcs, this time from LOTR. The chapter ‘The Bridge of Khazad-dûm’ in FR sees the first fighting against orcs in the novel, and these orcs are of sterner stuff than the goblins of The Hobbit. Where one might even be tempted to feel sorry for the goblins blasted by the wizard’s wand in the episode in the cave in The Hobbit, one feels no such pity for the orc-chieftain in black armour, with red tongue and eyes like coals, who charges into the room and attempts to butcher Frodo on the end of his great spear. Similarly, the orcs who kidnap Merry and Pippin in The Two Towers (TT) demonstrate real cruelty, and the more realist style of writing only serves to highlight the genuine hardships: the whipping, the sore wrists, the hunger and thirst that they suffer.

There is one thematic difference between the two novels which is worth stressing. The goblins of The Hobbit seem to be acting independently, at least from the point of view of Thorin and Bilbo and their friends. There is never any sense that the Necromancer of Mirkwood (i.e. Sauron) is controlling them or guiding their actions; though he may well be involved, we are never told this, even when the goblins team up with the wolf-like wargs. Similarly, the dragon is a very independent self-seeking operator, and does not appear to be a creature of Melko, though that may be his origin. By contrast, LOTR is very similar to The Silmarillion in presenting orcs and other such beings as wholly dependent on their masters – that is, either Sauron or Saruman – who have bred them or even in a sense created them. This last point throws up a whole host of problems, theological and philosophical, that have exercised the commentators about whether any creatures can be created wholly evil and irredeemable.7

In ‘Over Hill, and Under Hill’ in The Hobbit the true nature of the goblin captors only becomes clear when the action pauses after the goblins with their prisoners reach the great cavern in the heart of the mountain. Here the narrator stops to evaluate the nature of goblins, emphasising their cruelty and wickedness, their filth and untidiness, and their skill in mining and engineering: ‘they make no beautiful things, but they make many clever ones’. It is perhaps here that the ‘mischievous’ connotations of the word goblin begin to fade and the reader begins to worry. Speculating further in his colloquial style, the narrator suggests that it is ‘not unlikely’ that goblins and orcs eventually invented all the machinery of modern warfare, ‘especially the ingenious devices for killing large numbers of people at once’. Goblins, the narrator asserts, take delight in ‘wheels and engines and explosions’. Clearly this is Tolkien’s personal view of modern warfare, and it is found little changed in many of the asides and comments in his published letters, for instance in his comments on air raids that he makes during the Second World War. Orcs, he declares, are to be found on both sides of a conflict, even in wars that are morally justified.8

Attitudes to war

As Diane Purkiss has rightly pointed out, The Fall of Gondolin is Tolkien’s war story, a distillation of his Great War experience into the form of ‘his own epic romance version of the Somme’.9 And although, as we have just seen, the story of Tuor’s sea epiphany and mountain quest was based on earlier pre-war experiences, these two plot elements nevertheless form a necessary prequel to the main part of the narrative: the battle in which the great impregnable city of Gondolin falls to the forces of Melko. The immediate context for the composition of that narrative was Tolkien’s participation as a soldier in the Great War, a shattering experience, for it was a war which killed two of his close friends and effectively put an end to the TCBS, the first literary circle to which the youthful writer had belonged. Tolkien himself saw active service as a signals officer at the Battle of the Somme before contracting the trench fever which brought about his return to England, where his convalescence outlasted the duration of the war.

Tolkien had been ready to enlist as soon as he had finished his degree at Oxford in 1915. This was not unusual; there was huge social pressure on young men to fight (from families, girl-friends, local communities) whether they wanted to or not. And most young men decided to fight. A dialogue in The Book of Lost Tales, probably written during Tolkien’s time in France or shortly afterwards, gives literary expression to the reasons for those decisions. In Tuor and the Exiles of Gondolin the protagonist Tuor delivers his message from Ulmo of the Valar gods, bidding the people of Gondolin prepare for war, but his plea is firmly rejected by King Turgon in his pride and indignation, for he simply will not risk his people in a battle against the Orcs, nor, so he says, will he endanger his city.

Gondolin is a hidden kingdom analogous to Switzerland, a city on a plain surrounded by a ring of apparently impenetrable mountains, and Turgon is reliant on the landscape and the city’s defences and a policy of neutrality based an unwillingness to risk his resources in all-out war against the encroaching forces of Melko that have overrun most of the Great Lands. And he is indignant that the paths across the perils of the sea to Valinor and the home of the Valar are closed, and none of his messengers have ever come through or returned from their voyages successfully. Tuor’s point by contrast is that there is no choice: the encroaching enemy has to be stopped or they will take over the world, but if Gondolin will fight, despite the hardship that will ensue, Melko’s power will be diminished.

Tolkien was admittedly not a British jingoist, but he was at the very least an English patriot, and he felt that right and justice was on the side of the Allies, and that the war had to be fought. He had heard lectures on the poet Rupert Brooke, and friends such as G.B. Smith had encouraged him to read this poet’s verse. No doubt he knew Brooke’s lines:

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England.

And perhaps he knew and recognised something of Thomas Hardy’s cyclical view of history in his poem ‘In Time of the “Breaking of Nations”’:

Only a man harrowing clods

In a slow silent walk

With an old horse that stumbles and nods

Half asleep as they stalk.

Only thin smoke without flame

From the heaps of couch-grass;

Yet this will go onward the same

Though Dynasties pass.

Yonder a maid and her wight

Come whispering by:

War’s annals will cloud into night

Ere their story die.

But for Tolkien in his literary work it is also the passing of dynasties and war’s annals that interest him; for these are seen to be as equally important as the lives of ploughmen, farm labourers and rural lovers. The subject matter of his stories deals with both.

Depictions of modern warfare

Tolkien is often presented as an admirer of courage in the face of the enemy, and there is much truth in this, though not everyone, he concedes, is made of such stern stuff. For Bilbo in The Hobbit, the final terrible battle is the most dreadful of all his experiences, with good reason – since the slaughter is immense, though not reported in detail. The narrator adds ironically that it is the experience Bilbo was ‘most fond of recalling long afterwards’ (The Hobbit, chapter 17).

There is ambivalence in Tolkien’s attitude to war; it is certainly peace-loving, though not pacifist. As his letters reveal, he hated learning the business of killing; he disliked the vulgarity of life in barracks and training camps; he hated the mechanisation and casual brutality of modern warfare. For an example, consider the following passage:

Time passed. At length watchers on the walls could see the retreat of the out-companies. Small bands of weary and often wounded men came first with little order; some were running wildly as if pursued. Away to the outward the distant fires flickered; and now it seemed that here and there they crept across the plain. Houses and barns were burning. Then from many points little rivers of red flame came hurrying on, winding through the gloom, converging towards the line of the broad road that led from the City-gate to O…

The extract reads like a typical account of a retreat back to a defended town during the early stages of the Great War of 1914–18: perhaps a diary entry by Siegfried Sassoon, or a passage from Goodbye to All That by Robert Graves.

As I expect many readers will have realised, however, the final place-name should in fact read ‘Osgiliath’, revealing that the passage occurs in the chapter ‘The Seige of Gondor’ in The Return of the King (RK), where Tolkien returned to his theme of the siege of a great city. Apart from the similar names of Gondolin and Gondor (based on a root gond meaning ‘stone’ in Tolkien’s invented language) there are further parallels to be drawn between the two besieged cities. Possible real historical resonances include the siege of Troy by the Greeks (Tolkien was steeped in the Classics at school), and the siege of Byzantium by the Turks. The two cities of Gondolin and Gondor both represent the height of urban civilisation at the time when the story is set – the word civilisation of course deriving from Latin civitas, city. Both cities have great magical trees at their heart, the two trees in Gondolin recalling the splendour of the Trees of the Moon and Sun in Valinor, the land of paradise in the West, as depicted in The Silmarillion. The dry tree in Gondor is symbolic of the dead royal line in that city, which is ruled now by stewards awaiting the return of the king.

The sieges, though written in very different styles, are vivid and convincing pieces, and the same may be said of the dragon Smaug’s attack and siege of Laketown in The Hobbit. Tolkien is a writer who has seen the details of war at first hand. There is the sense of preparation, the arrival of reinforcements and preparation for bombardment; the individual at odds with the world, trying desperately to find out what is happening, frustratedly questioning orders given from high command that contradict other orders given earlier on the same day. As these and many other passages show, and as many commentators have remarked, Tolkien’s experiences on active service in the Great War fed in a number of ways into his writing, lending it authenticity. One need only read these episodes in conjunction with the account of the war in John Garth’s biographical study Tolkien and the Great War to realise the truth of the assertion.10

Even the fantastical and terrifying weapons of iron, bronze and copper, and burning fire that Melko designs for the assault on the city of Gondolin11 are plausible in terms of the disgust that Tolkien felt for weapons of mass destruction and products of the modern technology of war, such as tanks and poison gas and bomber-planes. The description in The Book of Lost Tales of Melko’s cunningly contrived technical weaponry almost sounds like the ethnological perspective of a writer or narrator (the tale is indeed being told by Littleheart, son of Voronwë) towards a technology that he perceives closely but does not fully comprehend.

Similar are the battle scenes, which again are given through Littleheart’s perspective, and expressed in the archaic literary language that Tolkien used at this time. But the scene where the fire-drake is forced into the deep waters of the great fountain of the royal square is nevertheless vividly done, and from a modern perspective it is reminiscent of technological warfare, or even a gas attack. The pools of the great fountain on the square are instantly transformed into steam and a cloud of vapour rises and hangs over the city. The square is filled with blinding fogs and scalding heat and the people fight each other in their blind panic until a rally of men gather around the king.12 With this episode might be compared the moment when the stricken Smaug falls onto the town of Esgaroth, splintering it to sparks and embers; the lake roars in and a vast white fog leaps up, lit by the moonlight (The Hobbit, chapter 14).

As was argued in chapter 3, Smaug is a real dragon, not an allegory, but nevertheless symbolic or allegorical readings of the story suggest themselves: at one point he is a kind of Leviathan, with biblical overtones. Similarly, an aspect of the battle for Gondolin that invites symbolic reading is the description of the two forces arrayed against each other. Where the men of Gondolin are pictured as belonging to great chivalric battalions, with heraldic devices and splendid accoutrements (not unlike the various groupings in Morris’s novel House of the Wolfings), the forces of Melko are, as we have just seen, the epitome of ugly, perverted technology, and such detailed imagery may be one of the essential themes that give this story its rather grim, relentless fascination. By contrast the grim parts of The Hobbit – Smaug’s attack on Esgaroth and the final ‘terrible battle’ – are shorter and more contained.