Chapter Thirteen

Early lessons in philology

IN FEBRUARY 1973 Tolkien wrote a note on the pastedown of the well-thumbed and battered family copy of Chambers’ Etymological Dictionary that he had owned since childhood. The note records for posterity the fact that this dictionary marked the start of his interest as a child in language and philology. In fact, it was so well used that the introduction to the dictionary, in which the user was initiated into the mysteries of Lautverschiebung and other technical terms, became so tattered that it fell out and was lost.3 The German technical term Lautverschiebung (literally ‘sound shift’) is a key one in historical philology; it refers to the sound changes, or rather patterns of sound change, that have been observed by historical linguists in various languages. The classic example is ‘Grimm’s Law’, formulated by Jacob Grimm (brother of Wilhelm Grimm and co-author of Grimms’ Fairy Tales). Grimm showed that a word in a Romance language beginning with p-such as Latin pisces or Italian pesce (or even Spanish pez and pescado) is related by a regular consonant shift to the equivalent or cognate word in a Germanic language, where it begins with f-: thus Old English has fisc and Danish fisk and modern English fish. The interrelation of the European languages is one of the initial fascinations in the study of philology.

It was at King Edward’s School Birmingham that Tolkien’s predilection for language history took an intensively philological turn. His official education went through the traditional curriculum of an English public school, with its heavy emphasis on the Classics: the intense study of the Latin and Greek languages, and the reading of the literature and history of the Classical periods. Such a syllabus had existed for centuries, and in many nineteenth-century schools Classics had been literally the only academic subject studied, pupils being steeped – with good and bad results depending on the pupil – in the languages of ancient times.4 Though by Tolkien’s time the syllabus had been broadened and reformed, it still encouraged pupils to read and write Latin poetry and – perhaps with influence from the Cambridge school of Latin studies – even to speak and debate in the language. ‘I was brought up in the Classics’, Tolkien once said in a letter to Rob Murray, grandson of Sir James Murray, the first editor of the OED; Homer was his first introduction to the appreciation of poetry, and he discovered that he enjoyed the fresh association of the form of the word with its meaning – an experience he found when studying the poetry of a foreign language or poetry written in older forms of the English language, such as Anglo-Saxon.5

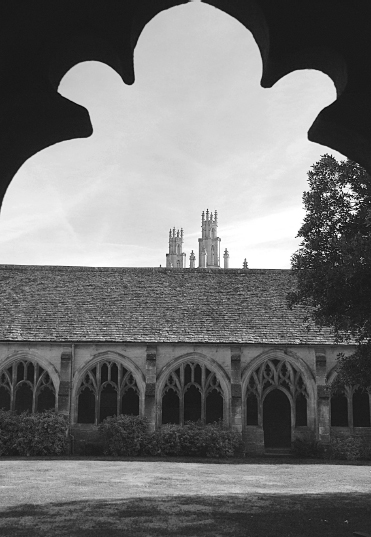

Fig. 13a Cloister and tower seen through arch

Anglo-Saxon and The Making of English

One lively introduction, Henry Bradley’s The Making of English, which Tolkien confessed to having read with delight, resonates well with Tolkien’s experience of languages as a boy, both at home and at school. Indeed, Bradley appeals to exactly that kind of schoolboy reader (the gender bias is unconscious), for he begins with the core vocabulary of English, presenting it by means of what he calls ‘the likeness of German and English’:

An Englishman who begins to learn German cannot fail to be struck by the resemblance which that language presents to his native tongue. Of the words which occur in his first lessons because they are most commonly used in everyday conversation, a very large proportion are recognisably identical, in spite of considerable differences of pronunciation, with their English synonyms.6

Bradley gives an illustrative list of resemblances, beginning with the family relations of Vater (father), Mutter (mother), Bruder (brother), Schwester (sister); then moving to the theme of country life with Haus (house), Feld (field), Gras (grass), Korn (corn), Land (land), Stein (stone), Kuh (cow), Kalb (calf), Ochse (ox); he turns next to common verbs singen (to sing), hören (to hear), haben (to have), gehen (to go), brechen (to break), bringen (to bring); and continues to chart the connections in adjectives, pronouns and prepositions. The list of resemblances is now expanded as Bradley brings in some rudimentary comparative philology, pointing out the phonetic correspondences:

| German | English | |

| z, tz, ss | t | |

| d | th | |

| pf, ff | p | |

| t | d | |

| -b- (in the middle of a word) | -v- |

Examples illustrate ‘the fundamental identity of a vast number of English words with German words which are very different from them in sound and spelling, and often also in meaning’:

Zaun, a hedge, is our ‘town’ (which originally meant a place surrounded by a hedge, a farm enclosure); Zeit, time, is our ‘tide’; drehen, to turn, is our ‘throw’, and the derivative Draht, wire, is our ‘thread’; tragen, to carry, is our ‘draw’; and so on.7

His exposition goes on to demonstrate the many similarities that exist in the grammars of the two languages, as well as the differences: the inflectional endings on verbs, adjectives and nouns. It is precisely these kinds of differences between German and English, he points out, that also distinguish present-day English from Anglo-Saxon (or Old English as it is also called).

Having begun with a series of facts familiar to his readers’ experience, Bradley now continues by exposing one or two popular fallacies, often still believed today: that English is somehow derived from German. This is manifestly not the case. In fact, the two languages have ‘descended, with gradual divergent changes, from a pre-historic language which scholars have called Primitive Germanic or Primitive Teutonic’. English and German are sister languages, with a parallel history. The rest of the Making of English goes on to show how Anglo-Saxon gradually evolved, in its grammar and vocabulary, into the modern language spoken today. Bradley traces the ‘the making of English grammar’ (chapter 2), and examines in detail ‘what English owes to foreign tongues’ (chapter 3), in particular the Norse influence on English, which came about through massive Viking migration and settlement in northern and eastern England in the Anglo-Saxon period, and then also the French influence, chiefly during the ascendancy of French as a prestige language in England in the Middle Ages, and finally the influx of Latin words into the language during the Renaissance.

In brief, Henry Bradley’s book still constitutes a sound introduction to the way English developed and expanded over a millennium and a half, and provides a still valuable guide to the history and development of English words. It clearly helped to kindle Tolkien’s interests. Coincidentally, Tolkien later met and worked with Bradley and the two struck up a good working relationship.8 At the beginning of his career, from January 1919 to may 1920, Tolkien was employed on the staff of the OED, for which Bradley was senior editor from 1915 to 1923.

An Anglo-Saxon Primer

While still at school, then, Tolkien began studying extra-curricular languages, such as Anglo-Saxon (Old English). George Brewerton, a perceptive teacher of English and the Classics, placed a textbook of the language in Tolkien’s hands. Likely as not this was An Anglo-Saxon Primer by the Oxford philologist Henry Sweet, the standard introductory textbook in England at the time, or just possibly the same author’s First Steps in Anglo-Saxon.9 Both of Sweet’s primers give a summary of the language followed by texts for practice in reading the language; these reading sections would have provided Tolkien with interesting material, some with stimulating creative potential.10 The texts in An Anglo-Saxon Primer, for one, are well chosen for their descriptive and/or literary-stylistic qualities: passages from the Bible such as the Tower of Babel, Solomon and Sheba, or the Parable of the Sower; extracts from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; an interesting saint’s life set in ninth-century East Anglia, The Life of Edmund King and Martyr, by the writer Ælfric. There is not time or space to examine all these texts, but let us take two which stand out for their potential interest to Tolkien.

It is not hard to see why the philologist and linguist Henry Sweet chose the Tower of Babel as a passage for his Primer, nor why Ronald Tolkien, the schoolboy with a philological inclination, may have wished to study it. This narrative has symbolic potential for its moral content: a tale of hubris that harks back to an ancient time when the language of all people was one. In the Babel story, humankind is motivated by overweening ambition and has chosen to build a great tower. Depicted over many centuries in European art, the Tower of Babel in the biblical story is also the symbol of the perfect language, the Victorian philologist’s ideal narrative, a mythos of how the one language became divided and scattered into many different tongues and vernaculars.

Though the Old English narrative is a close paraphrase of the Latin Bible, two words in the text are worthy of note: boc-leden and steapol. The term boc-leden or Book-Latin neatly reflects the general situation in early medieval Europe, where Latin was the one principal language of written record – Tolkien in 1938 was to coin his own word on a similar pattern, elf-latin, referring to his own invented language Qenya.11 In medieval terms, book-latin was for the ‘literate’ while all other languages were for the ‘illiterate’. A notable exception to this attitude, of course, was England in the years before the Norman Conquest, when (Old) English became the second language of government and record.

In the Old English text, steapol signifies the tower of Babel itself, clearly the modern English word ‘steeple’, here signifying a construction that is steap (exceedingly tall), perhaps a prelude to the many tall towers that feature in Tolkien’s writing, from Tower of Pearl in ‘The Happy Mariners’ to the Necromancer’s tower in The Hobbit to the Two Towers of LOTR.

Select passages from the Chronicle constitute the next chapter of Sweet’s Primer, and these undoubtedly had an influence on Ronald Tolkien’s developing sense of early literature. A chronicle is a set of brief records or annals – the years are listed and important events are briefly noted alongside the relevant date. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was one of the first sets of annals in Europe to be recorded in a vernacular language rather than in the Book-Latin. This is its attraction to philologists: the ancientness of its language, the suggestiveness of its linguistic forms. It can be shown that Henry Sweet felt strongly this enticement: his scholarly article on the vestiges of old poetry preserved in the language of the Chronicle is a paradigm of philological speculation, the process of reaching back into the past of a word or phrase in order to reconstruct the hidden concept, or the hidden poem that lies behind it.12 In one instance, there is a record of a battle in 473 AD between Hengest and his son Ash, leaders of the Engle, the ‘Angles’ or ‘English’, and the Wealas, literally ‘the foreigners’, also referred to as the Brettas – in other words, the Britons (text here adapted from Sweet’s Primer):

Her Hengest and Æsc ge-fuhton with Wealas, and ge-namon un-arimedlicu here-reaf, and tha Wealas flugon tha Engle swa swa fyr.

[Here Hengest and Ash fought with the foreigners, and took countless plunder, and the foreigners fled the English like fire.]

Here the crucial phrase depends on alliteration of f-sounds on fought, fled, fire, and translates quite literally into the present-day language as ‘the foreigners fled the English like fire’. Sweet’s speculation was that the Chronicle entry was a memory or an echo of an old poem long since lost, for Anglo-Saxon poetry used alliteration as the basis for its rhythm and metre. And Tolkien followed suit, at least in creatively re-imagining contexts for Old English poems in the legendary world he was inventing and discovering. He even imagined through his Ælfwine legend a situation in which a speaker of Old English would come to record the events of The Silmarillion in his own language. In such texts as the Annals of Beleriand, therefore, he records the legends in Old English, in its typically sparse, annalistic prose style.13

The appeal of philology

For Tolkien, above all, language study had an aesthetic appeal. In his view, the riches of a language were to be found in what linguists would term its phonology, in its system of phonemes or meaningful sounds, and their combinations, and in the rule-based patterning of those phonemes into words. This is Tolkien’s celebrated language-aesthetic.14 While still at school, he discovered it in Anglo-Saxon (i.e. Old English), as we have seen, but also in the related early medieval language Gothic, spoken by the Goths, a nation from Scandinavia and the Baltic that spread across Europe in the fifth century during the decline and fall of the Roman empire. Records in Gothic chiefly survive through a Bible translation made by bishop Ulfilas in the fourth century, a proponent of the teachings of Arius, which eventually lost favour in the western Church. The kind of speculation that followed from this, the might-have-been of history, was that, if Arius and Ulfilas had been more orthodox in their Christianity, Gothic could have become one of the great languages of the medieval church, alongside Greek and Latin.

Tolkien first came across this language in the Gothic Primer by Joseph Wright, the professor who was to become his tutor in comparative philology at Oxford. He later recalled ‘the vastness of Joe Wright’s dining-room table’ where he sat ‘alone at one end learning the elements of Greek philology from glinting glasses in the further gloom’. Wright, an autodidact from a Yorkshire working-class background, was a rigorous and demanding tutor, and must have conducted his university tutorials from the comfort of his own home, a common practice at that time, especially for professors.15 The Gothic Primer gives a grammar and a few passages, all taken from the Gothic version of the Gospels, the only major text extant in this language. This fact is significant, for there is no surviving poetry in Gothic to provide any kind of more strictly literary or poetic enjoyment. Nevertheless, for Tolkien the encounter with Gothic was akin to poetic enjoyment, and it became a creative catalyst: he attempted on its basis to invent, or in a way to reconstruct and re-invent, a similar ancient Germanic language in which other more strictly literary texts could then be produced. His love of Gothic, then, was strictly philological – that is, stemmed from ‘a love of the words’.

Likewise also was his attraction to Finnish, which he discovered as an Oxford undergraduate while supposedly working towards his intermediate examination (known at Oxford University as Honour Moderations); at the time he was studying the Classics, though he subsequently changed to medieval English studies for the second half of his degree. The attraction of Finnish was its mythological literature, especially the nineteenth-century collection of ballads known as the Kalevala or Land of Heroes. Its mythical themes, heroic stories and cold bright northern landscapes fascinated Tolkien, and inspired him to write an appreciative essay which he delivered as an undergraduate paper to the Sundial Society at Corpus Christi College, Oxford on 22 November 1914 and then again to the Essay Club at Exeter College, Oxford in February 1915. This paper, now published, demonstrates at first-hand his love of the archaic literary style and above all of the texture of the Finnish language itself, which he sees as euphonious and musical, and ‘anything but ugly’.16 He later regarded his discovery of Finnish as a defining moment; in a letter to W.H. Auden in 1955 he compared his finding the Finnish grammar in Exeter College Library to discovering a wine-cellar filled with strange intoxicating vintages.17

Fig. 13b Quad at Exeter College

Finnish thereafter became the basis of his Quenya and (to a lesser extent) Sindarin, the invented languages that were to provide the nomenclature, and hence generate the characters, personalities and even the whole narratives, of his fiction. As the two talks he gave to the Oxford college essay clubs show, all this creativity had started while he was still a student supposedly studying Latin and Greek. With so many extra-curricular linguistic interests, Tolkien did not perform outstandingly in his Honour Moderations in Classics, and his Exeter College tutors encouraged him to switch to the School of English for the second half of his undergraduate degree.

In these early encounters with Gothic and Finnish, it must be said that Tolkien was certainly not unique, nor was he the first to feel in this way the pull of philology as language-aesthetic. The following are a few examples from the late nineteenth-century world of language studies. A classic case is the German-trained philologist Friedrich Max Müller (1823–1900), Professor of Comparative Philology at Oxford, whom Tolkien was to mention in his later lecture on fairy-stories. Müller famously lectured on the ‘Science of Language’ in the 1860s; the published lectures sold widely, in many editions, and in them Müller expresses a similar feeling for language, in his case the experience of studying Turkish, a language related generically to Finnish. Though Müller is rather more focussed on the beauty of structure rather than the euphony of sound, his reaction is not unlike Tolkien’s initial response to the discovery of the sounds and textures of Finnish:

It is a real pleasure to read a Turkish grammar, even though one may have no wish to acquire it practically. The ingenious manner in which the numerous grammatical forms are brought out, the regularity which pervades the system of declension and conjugation, the transparency and intelligibility of the whole structure, must strike all who have a sense of that wonderful power of the human mind which has displayed itself in language.18

Like Tolkien with Finnish, Müller does not wish to acquire a practical ability to speak Turkish: rather, he is impressed by its pattern and structure.

Sound symbolism and onomatopoeia

A younger contemporary of Max Müller was the Oxford anthropologist Sir Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917), who became the first person to hold a chair in the new academic discipline of anthropology. Tylor was particularly fascinated with language and was well read in the scholarship of the German philologists; he particularly appreciated the aesthetic aspects of Jacob Grimm’s work, for instance on the phenomenon of vowel gradation, by which a word can symbolically express fine ‘colourings’ or distinctions of meaning, simply by ringing the changes on its root vowel. Here, for example, is Tylor’s discussion of the sound-symbolism inherent in the words stand and stop; the passage is characteristic of nineteenth-century philology at its most lively and enthusiastic:

Thus, again, to stamp with the foot, which has been claimed as an imitation of sound, seems only a ‘coloured’ word. The root sta, ‘to stand’, Sanskrit sthâ, forms a causative stap; Sanskrit sthâpay, ‘to make to stand’, English to stop, and a foot-step is when the foot comes to a stand, a foot-stop. But we have Anglo-Saxon stapan, stæpan, steppan, English to step, varying to express its meaning by sound into staup, to stamp, to stump, and to stomp, contrasting in their violence or clumsy weight with the foot on the Dorset cottage-sill – in Barnes’s poem:–

‘Where love do seek the maïdens’s evenèn vloor,

Wi’ stip-step light, and tip-tap slight

Ageän the door.’

By expanding, modifying, or, so to speak, colouring, sound is able to produce effects closely like those of gesture-language, expressing length or shortness of time, strength or weakness of action, then passing into a further stage to describe greatness or smallness of size or of distance, and thence making its way into the widest fields of metaphor.19

By ‘metaphor’ is meant here the metaphorical use of certain vowel-sounds such as the effect of lightness in the vowel in step, contrasted with the heaviness expressed by the vowels in stamp and stomp. Tylor here combines historical inquiry with analysis of the structure of present-day English, and he cites the Dorset dialect poetry of William Barnes, a poet with whom Tolkien had affinities, both in his love of dialect and linguistic variation and in his preference for the Old English and Germanic roots and stems of the English language.

Another poet thinking along the same lines was Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose experiments with sprung rhythm and alliterative metre might well have appealed to Tolkien. Hopkins had the same love of etymological connections that we also find in Tolkien’s work. In the following paasage he speculates on the origins and connections of the word grind:

Original meaning to strike, rub, particularly together. That which is produced by such means is the grit, the groats or crumbs, like fragmentum from frangere, bit from bite. Crumb, crumble perhaps akin. To greet to strike the hands together (?) Greet, grief, wearing, tribulation. Gruff, with a sound as of two things rubbing together. I believe these words to be onomatopoetic. Gr common to them all representing a particular sound. In fact I think the onomatopoetic theory has not had a fair chance. Cf. Crack, creak, croak, crake, graculus, crackle. These must be onomatopoetic.20

This diary entry of September 1863 alludes to the work of F.W. Farrar, who had proposed the theory that human language had originated in cries imitative of the sounds of the external world.

One of the new turning points in science in the mid-1860s was the realisation of the great age of the earth. Rather than being a few thousand years old, as many scholars and scientists had previously assumed, the evidence of geological strata, fossils and biological variation pointed to the earth being millions of years old, and to modern humanity itself being tens of thousands of years old. No longer was it possible therefore to regard an ancient recorded language such as Sanskrit as fairly close to the original human language, the tongue spoken by humankind at a ‘primitive’ stage of development; for example, at the time of the Tower of Babel. The difficulty is that all languages for which we have records are relatively speaking ‘modern’, for two reasons: first, languages were not recorded in writing for many millennia in the unwritten story of humanity; and, second, it is impossible to find a ‘primitive language’ since (apart from socially constructed pidgins) all natural human languages in existence have complex systems of vocabulary and syntax. Despite the chronological problems involved, however, speculations on the origin of language, often linked to an aesthetic of sound symbolism, continued to enthral philologists and anthropologists at the end of the nineteenth century. Max Müller, rejecting Farrar’s imitative–onomatopoeic theory, proposed his own, equally speculative, theory that phenomena of the external world ring and resonate and so give rise to the sounds of human speech that are consonant with them.

In the early twentieth century, when Tolkien was as it were a trainee in the field, historical philology remained traditional in its methods, even if the philologists had to make some allowance for the new sophistication of the exponents of ‘linguistics’, such as the great Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure and his structuralist disciples, who further developed his work from the 1920s onwards. Tolkien described himself as old-fashioned in his philological work; the old theory and methodology suited him. Not surprisingly, continuations of nineteenth-century language reflection are found among the Inklings, the loosely associated group of Oxford scholars and writers headed by C.S. Lewis to which Tolkien belonged. As Verlyn Flieger has recently argued convincingly, the Inkling Owen Barfield’s book Poetic Diction was a key formulation.21 In Barfield’s insistence that words preserve an ancient unitary meaning – this despite the ceaseless processes of semantic change – Barfield seems closer to the originary linguistic roots of William Barnes, Farrar and Max Müller (even though he disagreed with them) than he does to anything in contemporary twentieth-century structuralist linguistics or linguistic philosophy. Barfield’s ideas do, however, chime well with some recent attempts to explore the notion of phono-semantics and the connection between sound, meaning and landscape.22

Reconstruction as a method

All this language background is highly relevant to Tolkien’s epiphany, his discovery of the Anglo-Saxon word éarendel in the poem Christ I. It was a moment of aesthetic appreciation, and the effect was exhilarating, as though he was about to grasp something remote and unusual, just beyond his fingertips.23

Tolkien eventually used this word denoting the evening star as a name in his own mythology, in an elaborate process of reconstruction and re-invention that is famous in Tolkien studies.24

But, as we are about to see, éarendel was not the only word that he adopted creatively from earlier forms of English. He was now (from 1913) ‘studying A-S professionally’.25 The course was demanding, and the tutor, the well-respected Kenneth Sisam, was rigorous but also inspiring in his coverage of set texts. The main edition from which the set texts were drawn was Henry Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Reader, the standard textbook since its publication in 1876; by the time Tolkien was at university it was already in its eighth revised edition (1908).26 Just as his Primer was aimed at beginners in the language, Sweet’s Reader took them to the next stage; it consisted of a short grammar (aimed at advanced students) followed by a large anthology of reading texts in both prose and verse, selected by Sweet from all the periods and regions of Old English literature before the Norman Conquest. Notes and a glossary completed the book. Sweet’s principle in presenting the texts was to keep the notes to a bare minimum and to refrain wherever possible from historical or cultural commentary, for he felt that it was the role of the teacher to comment on the texts when using the Reader with students.27 The result of the policy is that the small number of cultural comments that are actually included in the textbook stand out prominently, and it is arguable that they influenced student users of the Reader considerably. Two examples are telling. Chapter 27, headed ‘Selections from the Riddles’, has the rubric:

Many of these riddles are true poems, containing beautiful descriptions of nature.

While chapter 28, ‘Gnomic Verses’, has the following comment:

The so-called gnomic verses show poetry in its earliest form, and are no doubt of great antiquity, although they may have been altered in later times. While abrupt and disconnected, they are yet full of picturesqueness and power; the conclusion of the present piece is particularly impressive.

The problem with a comment of this nature is that it goes back to the first edition of 1876, when Sweet, despite some pioneering linguistic work that was ahead of its time, was still under the spell of the older philology. At that time, as was pointed out above, the scientific demonstration of the great age of the earth had only recently been made and the new ways of thought were taking a while to filter through. Even a rigorous, forward-thinking scholar like Sweet still felt that the writings in the earliest Old English must be ‘of great antiquity’, when in point of fact thousands of years must actually separate the writers of Old English from ‘poetry in its earliest form’. Clearly the attitude was entrenched and difficult to dislodge. The temptation was to date Old English poetry far earlier than it really was, or to see it as somehow a vestige or record of something far more ancient.

In fact, the Gnomic Verses appear in a manuscript of the eleventh-century version C of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and though it is likely that these versified proverbs or maxims are traditional, the composition of the poem need not necessarily be very ancient: it is possible that the verses were put together to accompany the new manuscript of the Chronicle that was compiled in the 1040s. The title of course is not part of the original poem, for none of the manuscripts of Old English poetry contain titles. These have mostly been invented by nineteenth-century scholars, and their successors employ them as convenient labels. Sometimes a poem title is changed: nowadays this particular poem is referred to as Maxims II. Not a terribly inspiring title for a poem, it must be admitted, but the Roman numeral serves to remind scholars that there are two very similar poems of this genre in the surviving corpus of Old English poetry. Since the term ‘gnomic’ suggests ‘wisdom’, or even ancient wisdom, the nineteenth-century title of the poem has now been replaced. The antiquarian bias of Victorian Anglo-Saxon studies is the flaw, as it were, in the traditional philological method of reconstruction of lost earlier realities.

Nevertheless, there is something very attractive in the reconstructive approach, and Tolkien certainly must have found it so; for him the philological method of reconstruction was creative and stimulating. If we look for instance at the opening lines of the Gnomic Verses in the textbook that he studied, a rich variety of Tolkienesque terms and concepts simply leap out from the page. Here is the Old English text (I have modernised the spelling of the letter thorn as ‘th’ for the benefit of readers who do not know Old English); a translation follows:

Cyning sceal rice healdan. Ceastra beoth feorran gesyne,

orthanc enta geweorc, tha the on thysse eorthan syndon,

wrætlic weallstana geweorc. Wind byth on lyfte swiftest,

thunor byth thragum hludast. Thrymmas syndan Cristes myccle.

Wyrd byth swithost.

[The king must rule over a realm. Cities are conspicuous from afar, those which there are on this earth, the ingenious constructions of giants, ornate fortresses of dressed stones. The wind in the sky is the swiftest thing and thunder in its seasons is the loudest. The powers of Christ are great: Providence is the most compelling thing.28]

This is a poem about kingship, the marvels of old cities, the power of the elements, the strength of wyrd, an old word for ‘fate’; even conceptually there are echoes of Tolkien’s world here.

Line 2, with the words ‘orthanc’ and ‘enta geweorc’, is the clearest verbal resonance: the original meaning is ‘cunning work of giants’, and rather like the proverbial ‘standing on the shoulders of giants’ this maxim probably referred not to literal giants but to the skills of the Roman architects and masons who built what they called the castra – these are the towns that the Anglo-Saxons named ceastra (pronounced roughly as ‘chastra’); in other words, the ancient fortified ‘chesters’ such as Chester or Winchester that were and still are to be seen across the length and breadth of Old England, among the oldest stone-walled cities in the country. When Tolkien presumably turned to the glossary in Sweet’s Reader he would have found that orthanc is an adjective meaning ‘cunning’; and with the help of grammar and glossary he would have found that ent means ‘giant’ and enta means ‘of giants’, while geweorc is in fact the perfective prefix ge-plus the noun weorc meaning ‘work, fortification’. Here already are the first inklings of an idea that was to take many decades to crystallise in Tolkien’s mind as he wrote LOTR in the 1940s. First came Orthanc, the tower of the wizard Saruman, a name which (as Shippey has pointed out) is searo-mon in standard Old English and signifies ‘the cunning man, the artificer’. With this image in mind Tolkien hit upon the ents, the tree-giants of Fangorn Forest. The two images then were linked in TT as two symbolic figures in the War of the Ring: on the one hand Treebeard and the ents representing nature and the voice of defenceless trees; on the other hand Saruman the artificer, the industrialist and destroyer of the environment. The juxtaposition of the two images is the revenge of nature against artifice, the symbolic theme of the narrative. Intrigued by the implications of the Old English words, Tolkien adapted them to the narrative world of his own stories set in ancient times.

Old English words and concepts in The Hobbit

As with orthanc and ent, the same process took place with other Old English words; with regard to The Hobbit the following non-exhaustive list covers some of the more significant: ælf, beorn, eorcanstan, orcneas, smugan, wearg. All these words appear in The Hobbit in a modernised form, either as a type of being or creature in the case of elf, orc and warg, or as a proper noun in the case of Beorn, Arkenstone and Smaug (from the verb smugan: to investigate, worm one’s way into something). For discussions of these particular words the reader can do no better than turn to the writings of Tom Shippey, in particular The Road to Middle-earth, in which he pioneered a philological approach to Tolkien’s writings, and to The Annotated Hobbit by Douglas Anderson.29 An alphabetical treatment of these and other words is to be found in The Ring of Words by OED editor Peter Gilliver and his colleagues.30 The following remarks highlight some of their findings and emphasise a few other points to be made about these once extinct Old English poetic words that had gone out of use in everyday English, until Tolkien revived them.

In its Norse cognate form, the word alf has already been encountered in the compound name Gandalf, one of the dwarves of Norse mythology, whose name Tolkien borrowed for his wizard with his staff (gand means literally ‘staff’). The Old English cognate was ælf, spelt with the old letter known as ‘ash’, a ligature or blend of the two letters ‘a’ and ‘e’. Ælf- is usually encountered as the first element in compound names such as Ælfræd and Ælfwine and Ælfgar, names common among the Anglo-Saxon nobility of tenth-century England. Alfred and Alwin and Elgar are their modern descendants, though the spelling complicates and partly disguises the etymology. The second element in the first instance is ræd, a noun which means ‘advice’ or ‘counsel’, hence Alfred means ‘advice of supernatural beings’ or ‘counsel of the elves’. An archaic word in present-day English is rede; and the modern German cognate is Rat (advice), heard for instance in Rathaus (town-hall), where traditionally counsellors meet. The second elements respectively of Alwin and Elgar are -wine (friend) (pronounced as two syllables ‘wi-nuh’) and -gar (spear). These were productively used to generate other names such as Eadwine/Edwin the Blessed Friend, a name that Tolkien used in his unfinished novel The Lost Road, and Eadgar/Edgar the Blessed Spear.

A passage in the poem The Dream of the Rood, the well-known Old English religious poem celebrating the victory of Christ at the crucifixion, which David Jones used in his poem In Parenthesis, provides a context for two other Anglo-Saxon poetic words that Tolkien adopted and made his own: beorn and wearg, which appear in their plural form beorn-as and wearg-as. Generically, the poem is a dream vision in which the Cross itself is given a personalised voice, telling the story of the Passion from his own perspective, lamenting how strong enemies (feondas), criminals (weargas) and warriors (beornas) – all these words appear to be near-synonyms in the rhetoric of the verse – carried the Cross to a hilltop where they raised it up.31 As was discussed above it is clear that Tolkien used his knowledge of the sister-languages and their cultures, especially Old Norse, when adopting words into Old English. The name Beorn is the case in point: its poetic meaning ‘warrior’ is coloured by its older meaning ‘bear’, which Tolkien then associated with the story of Bothvar Bjarki, the man-bear or shape-changer in Norse saga. As for wearg, this meant a criminal or outlaw in Old English; also spelt wearh, the word appears in the poem Maxims II, which declares that it is right and proper for a criminal to hang in order to atone for, or pay back for, crimes against humanity. The lupine nature of the word is found in the Old Norse cognate vargr meaning either ‘outlaw’ or ‘wolf’. Tolkien combined these two ideas in order to invent an intelligent but malevolent wolf-like creature that fitted the polarities of good and evil which he had fashioned for his mythology. As Tolkien himself pointed out, the spelling warg is an older form that points to the prehistory of the word in the original Germanic language that eventually gave rise over time to its descendants Old Norse, Old English and Old German.32 As with Eärendel from Old English éarendel, Tolkien used the method of reconstruction to create imaginatively a person or creature in the reconstructed ‘real world’ of prehistory who would fit the poetically rich term that he had come across in his study of the Old English language. This attention to finding the right word is part and parcel of Tolkien’s philology, and the success of his fiction depends very much on the suitability of his choice of words and, as we saw in chapter 5, his nomenclature, his finding the right name.

Fig. 13c Warg

Connected with this also is Tolkien’s attention to the right sound of his words, since his thinking was as much phonetic as it was calligraphic or typographic. He loved scripts and alphabets, but he also thought in terms of sounds as well as spellings, and when using his Tengwar script, for example, he spelt English words phonetically.33 (The Tengwar script can be seen, for example, in editions of The Hobbit on the large pot of gold in the picture of Smaug resting on his treasure.) The preference for phonetic writing was in keeping with the results of comparative philology, which showed to the satisfaction of most scholars (though there were sceptics) that on the whole Old English scribes wrote phonetically, using a consistent system of letter-to-sound correspondences. Their system for spelling vowels for instance followed very much the values of continental languages like Latin, Italian and German. Tolkien adhered to this traditional use of the roman alphabet in the names he used for people and places. The first syllable of Sauron, for instance, rhymes with ‘now’; the ‘au’ spelling represents the diphthong, the phonetic term for two vowels combined into one syllable, pronounced as though it is one vowel, with a glide between the sound ‘a’ of cat and the ‘u’ of full. The spelling ‘au’ in Tolkien’s nomenclature is one consistently used for that sound, as in modern German Haus, Maus, laut, which correspond roughly in their sound to their English cognates house, mouse, loud. The name Smaug should also be pronounced with the same vowel-sound. More difficult is the pronunciation of the diphthong in Eärendel. Learning to pronounce Old English can provide useful assistance here (as well as giving access to the riches of early English literature that Tolkien knew so well).34 In éarendel there are three syllables éa-ren-del, the first syllable having the open ‘æ’ sound which then glides briskly down to a short ‘a’ vowel; the name ‘Arundel’ spoken quickly comes close to the same sound.

One final pronunciation point concerns the ‘v’ sound in Tolkien’s plural noun dwarves, which he favoured over the traditional English proofreaders’ preference for dwarfs when he published The Hobbit; likewise the adjective elvish, which famously he preferred to the diminutive elfin; he also on occasions favoured roof–rooves on analogy with hoof–hooves.35 There was no letter ‘v’ in Old English: the final ‘-f’ of hrof (meaning ‘roof of a house’) was pronounced ‘f’, but between vowels the medial letter ‘-f-’ had the sound ‘v’ as in lufu, modern English ‘love’, or indeed the plural hrofas (rooves). The reader may be tempted to suspect that Tolkien’s love of Old English as a language to be heard and enjoyed also influenced the way he pronounced and wrote modern English.

Tolkien’s choice of words in The Hobbit

With respect then to the way Tolkien thought and felt about the living history of English words, it makes sense to cultivate an appropriate linguistic awareness when reading and thinking about his fiction. And occasionally, though of course not too often, it is worth taking a break from reading to linger over Tolkien’s choice of word and phrase. A highly illuminating exercise is to take a short but significant passage and examine the history of a selection of its words, using etymological dictionaries and glossaries (such as Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Reader) as well as the OED as a guide and reference tool.

One key passage, already alluded to in chapter 9 above, concerns the ‘thunderbattle’ in ‘Over Hill and Under Hill’ (The Hobbit, chapter 4) which prevents the travellers from crossing the Misty Mountains:

You know how terrific a really big thunderstorm can be down in the land and in a river-valley; especially at times when two great thunderstorms meet and clash. More terrible still are thunder and lightning in the mountains at night, when storms come up from East and West and make war. The lightning splinters on the peaks, and rocks shiver, and great crashes split the air and go rolling and tumbling into every cave and hollow; and the darkness is filled with overwhelming noise and sudden light.

The passage is of interest from a historical point of view in showing a word in the act of changing its meaning. In the adjective used to describe the emotional effects of the storm on the observer, this passage (published of course in 1937) demonstrates one of the last uses of the word terrific in its detrimental sense of ‘causing terror, terrifying’. The OED states this use is ‘now rare’ and cites the poet Milton as a first user of the adjective with this meaning in 1679, and gives a war report of 1914 as its last citation. The OED sense 2a, ‘of great size or intensity’, is first attested in 1743, while sense 2b, ‘an enthusiastic term of commendation: amazing, impressive; excellent, exceedingly good, splendid’, is first observed in 1871 and is still current. It is unlikely given the related pairing terrific/more terrible that Tolkien meant the word in this latter, positive sense, though we may be fairly sure that as a philologist he was aware of it.

The compound thunderstorm is a relative newcomer to the language, despite the fact that its constituent words thunder and storm both go back to Old English. The OED finds no trace of it until the seventeenth century, from which time it gains in popularity. Storms, however, are a long-standing veteran of the English lexicon. The word occurs for example in the windswept seascape of the Old English poem The Seafarer, where storms ‘beat’ the cliffs: ‘stormas thær stanclifu beotan’.36 The use here verges on the metaphorical, and, as the OED reports, a similarly figurative take on the word occurs in Beowulf (line 3117), where the meaning is transferred to warfare: ‘stræla storm’ – that is, a storm of arrows shot over the shield-wall, rather like the ‘hail of dark arrows’ shot at the dragon in The Hobbit (chapter 14). Thunder is another veteran, attested in Old English as thunor. Old English Thunor as a proper noun was also the Anglo-Saxon equivalent of the Norse god Thor, after which Thursday or Thunres-dæg is named.

The main theme of the passage is thunderbattle, Tolkien’s word to describe the situation when two separate storms ‘meet and clash’ – and ‘come up from East and West and make war’ – here the verb meet has the military sense of ‘to come together as rivals in a battle’ (OED meet, sense IVb). There is no OED entry at all for this compound thunderbattle. It is of course Tolkien’s original comic invention to play on the military connotations and replace the element -storm in thunderstorm with a word of full military import. The noun battle is one of the first French words to be introduced into English after the Norman Conquest; William I named the abbey founded on the site of his victory near Hastings as Battle, a name which the nearby village retains to this day. As the OED shows, the word derives from Old French bataille, which in turn goes back to Late Latin battualia from battu-ere (to beat). Similarly, the noun war is also a Norman import into the language (the Central French equivalent being guerre).

The mythic and warlike connotations of the word thunder and the compound thunderbattle may lie behind Tolkien’s introduction later in the same scene of the stone giants hurling their rocks at one another for a game and smashing them into the trees far below in the valley. Is this nature personification rather in the manner of the theories of animism propounded by Max Müller and E.B. Tylor that we discussed in chapter 9? The effect of the description is terrifying, though some critics have objected that such mythic personifications do not fit well into Tolkien’s overall concept. Elsewhere, in particular in his treatise On Fairy-stories, Tolkien was sceptical of the reductive attempts by the late Victorian armchair anthropologists to explain away the gods solely as personifications of the weather; for instance. the highly personable and irascible character of the god Thor ‘explained away’ as a personification of thunder.37

Probably with deliberate intent, Tolkien plays on a number of etymological connections in the onomatopoeic words he uses in this passage. The verb clash and the noun crash are related in sound and echoic sense, as is smash which appears later on the same page; splinter and split are both derived from Middle Dutch. Sometimes he also matches synonyms from different language origins. The matching pairs ‘rolling and tumbling’ and ‘cave and hollow’ are words of related meaning but different derivations: roll and cave from French; tumble from Old Low German but related to Old English tumbian (to tumble, leap, dance); hollow from OE holh (hole). The latter word holh (hollow) is related to hol (hollow place, cave, hole, den). A hollow is exactly the place the travellers are about to retreat to as the storm worsens. It is also a reminder of the word hobbit, which in the language of Rohan in LOTR (Part III, chapter 8) is holbytla or ‘hole-builder’; in this pseudo-etymology Tolkien actually invents an Old English word *holbytla (the asterisk marking it as hypothetical or reconstructed), in order to provide a life-history for his invented modern English word hobbit.