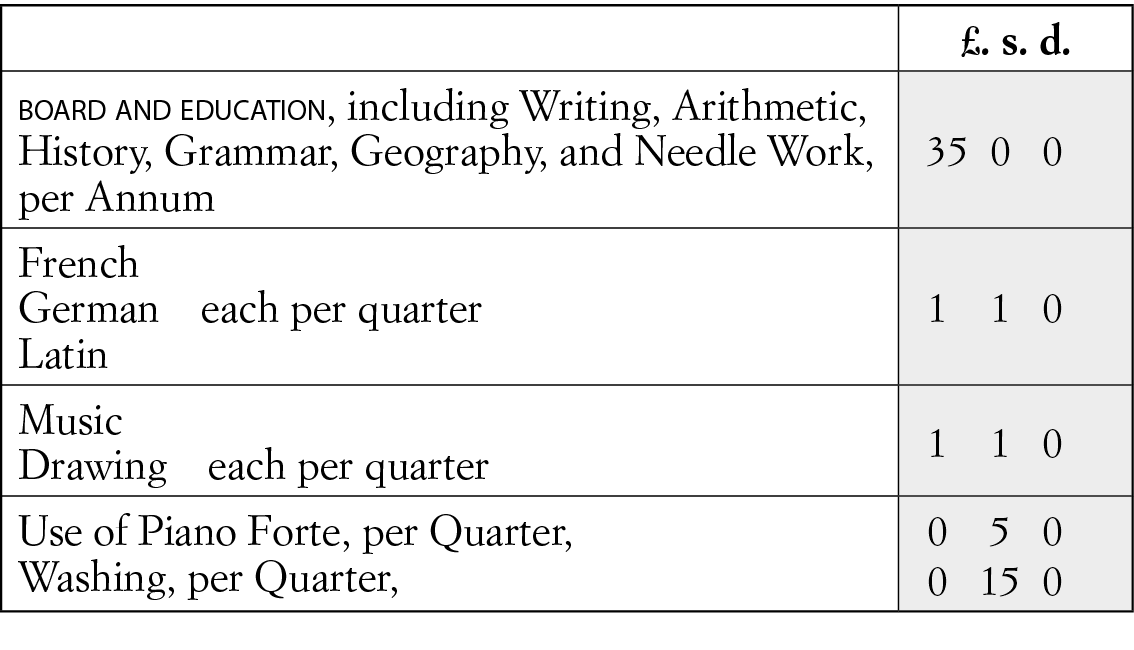

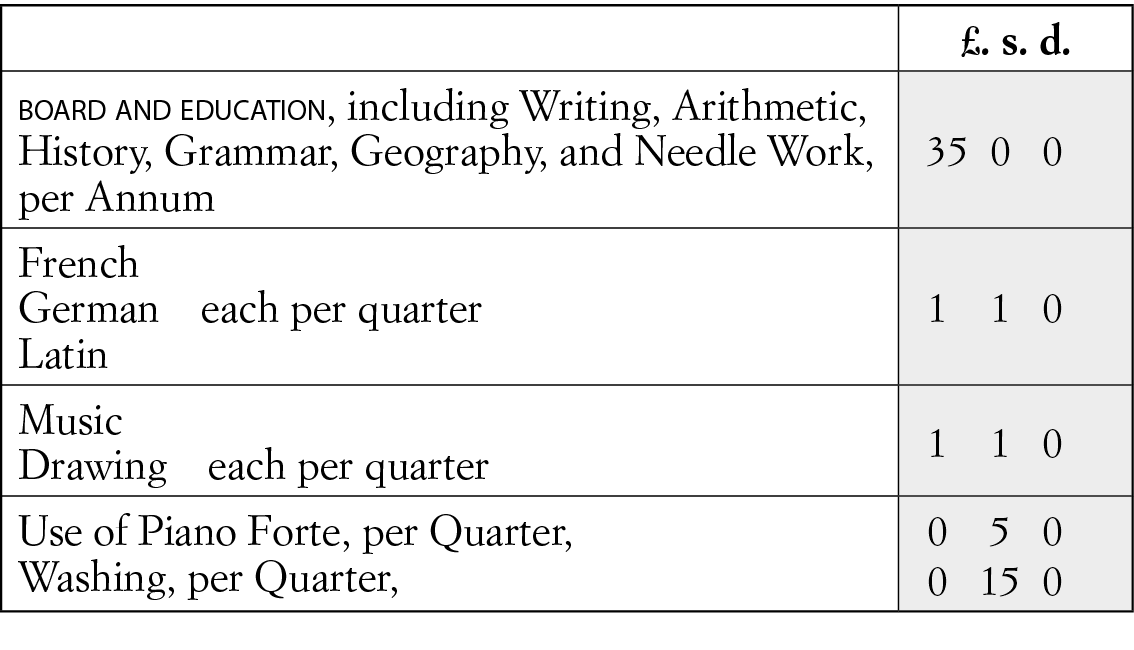

What do you think I have?’ said Charlotte hurrying into the kitchen. Without stopping to take off her shawl, she dropped a package on the table. My hands were thick with pastry dough, so she opened the package herself and propped one of the cards it contained against the mixing bowl, so that I might read it without touching.

The Misses Brontë’s Establishment

FOR

THE BOARD AND EDUCATION

OF A LIMITED NUMBER OF

YOUNG LADIES,

THE PARSONAGE, HAWORTH,

NEAR BRADFORD.

Terms.

Each Young Lady to be provided with One Pair of Sheets, Pillow Cases, Four Towels, a Dessert and a Tea spoon.

A Quarter’s Notice, or a Quarter’s Board is required previous to the Removal of a Pupil.

‘I had Mr. Greenwood make them up for us,’ said Charlotte. It was difficult to know if the hectic colour in her face came from excitement, or from the brutal wind that had been howling around the house for the last two days, though it was the middle of July. ‘We must ask everyone we know to distribute them. I’ll write to Ellen before I go back. Mary Taylor too. I’ve kept the fees low because we are so remote.’

‘Any sensible parent would think that an advantage,’ I said. I gave the pastry a quarter turn and dusted the rolling pin with more flour. On the range, the meat for my pie was simmering gently. ‘The air is healthier here.’

‘The important thing is to attract some pupils in the first instance,’ said Charlotte, barely listening. Her thoughts were running ahead of her, into the future. ‘Once we’ve some income, we might think about extending the house. We can always increase our prices later.’

The idea had come to her at Whitsun when she and Anne were home for a holiday, but she’d had no time to put it into action until now.

‘Anne and I might manage most of the teaching,’ she’d explained, the night before the two of them were due to return to work. ‘We’ll need to make some alterations, of course. And we must persuade Aunt. None of it can happen without her investment and you know how careful she is with money.’ The caution in her words belied her excitement. She’d circled the dining room table twice, then darted to the window and back again, a skittish marionette. It was a long time since I had seen her so animated.

‘A school of our own,’ said Anne, a gentle fire igniting in her eyes. Her face was drawn, and she was too thin. She insisted that her employers treated her with kindness and affection, but I knew what it cost her to live so far from home and among strangers. Even more so since the arrival in Haworth of William Weightman, the only one of Papa’s curates we’d ever been able to tolerate. Within days of taking up residence, William had become a friend to all. He was charming and attentive to each one of us—even I managed to exchange a word or two with him, and, like everyone else was half in love with his beauty—but more than once I’d caught him gazing at Anne on her visits home, noticed the flush on her cheeks as she perceived this.

‘Branwell seems remarkably settled at his little station so we might use his room,’ Charlotte went on. ‘Emily, you might give a few hours a week to help with music lessons, but the house will not run without your direction, certainly not if Aunt ever decides to go home to Penzance.’

I nodded, not yet ready to speak. The thought of filling the parsonage with chattering schoolgirls was abhorrent, but I could see that Charlotte’s scheme had advantages: the opportunity to make decisions for ourselves, the three of us living and working together, here in our own home, for the foreseeable future. With Martha growing more capable by the day and Charlotte, Branwell and Anne all working, it was becoming harder to defend my own lack of paid employment, even to myself. The thought of it had begun to mar the pleasure of my daily walks, even finding its way into my dreams of Gondal which had become full of failed expeditions and disastrous schemes, prisoners racked with guilt for their misdoings. I’d spent the last few weeks trying to find a new story for Rosina, the wife that Julius had abandoned when he fell in love Geraldine Sidonia, the mother of Augusta Almeda. I wanted Rosina to take a lover from the neighbouring island of Gaaldine, for the two of them to plot Julius’s assassination, but she couldn’t seem to stop feeling useless and sorry for herself.

‘I shall carry on working for a while longer,’ said Charlotte. ‘If I can bear it. You too, Anne, so that we can save as much as possible before we open.’

‘I could teach drawing as well,’ I’d said, a rare expansiveness coming over me. I might not mind the company of a child or two on an occasional walk either, so long as they had eyes and ears to notice what was around them and did not pester Keeper or expect me to talk. ‘What will Papa think about it? You know how he hates his routine to be disturbed.’

‘I will deal with Papa,’ said Charlotte, her voice ringing like an axe on stone.

Within a day, she had persuaded Papa of our plan and Aunt had agreed to invest in our Parsonage School.

‘It was remarkably easy,’ she said. ‘I bowed to Aunt’s good judgement in all matters and then reminded her of the need for clean sea air and proper society in one’s old age. All these years of being bound to Haworth.’

‘You really think she’ll go home?’ said Anne, looking troubled. We were silent for a moment. Though we teased Aunt for her fussy, exacting ways, her little snobberies and affectations, she had been part of our lives forever. It was hard to imagine this household carrying on without her.

Now, with a means to advertise our school, the plan began to feel possible. We hurried to send the cards to everyone we knew before Charlotte and Anne returned to work. The list was not extensive, but Ellen wrote to say she had pressed the information on all her acquaintances, and Reverend and Mrs. Franks promised to spread the news among their circles. Even Miss Wooler said that she would recommend us to any family unable to afford the fees at Roe Head, which was remarkably generous—she had once hoped Charlotte would return there to take up the Head Teacher position. I received a couple of enquiries in the post, and replied by return, but nothing came of these. Autumn passed in a flurry of ochre and russet and Charlotte’s letters from Rawdon grew despondent.

We should have fixed on another location. I thought of Bridlington at first, somewhere with more life. It’s no surprise that families would think twice about sending their daughters to such a lonely little spot. Think how bleak it is in wintertime.

It’s hardly lonely, I replied, in the briefest of notes. If anything the village was too crowded, the streets and alleyways teeming with men, women and children on their way to and from the mills every morning and evening, carts rattling up and down Main Street all day long, the horses straining at the steep incline, thud-thud as the dray wagon was unloaded, pink and white carcasses being shouldered into the butcher’s, the long, complaining queues for the water pump, for the public privy. And I’m not moving to Bridlington.

You have been too long at home, wrote Charlotte. Can see no fault in it.

Her next few letters were mainly about her dissatisfaction with her employer, Mrs. White, who seemed at one moment to offer friendship, as though the two of them were almost equals, and the next to treat my sister with more contempt than if she were the lowest of scullery maids. She was an intolerable woman, Charlotte said, of very little breeding. She enclosed a page from a letter that Mary Taylor had written to her. Though the death of Mary’s father the previous year had left the family with some financial difficulties, Charlotte’s old schoolfriend had managed to find enough money to travel in Europe. She wrote that she and her little sister Martha were now attending a school in Belgium, for the purpose of improving their French and learning some German. She had not quite settled on teaching as a career, she wrote, was even looking into the notion of emigrating to New Zealand where, apparently, opportunities were less codified, especially for women.

I tucked the page away in Charlotte’s writing desk for when she returned home, which was sooner than expected. She arrived late one evening in early December and went straight to bed, citing one of her headaches. It seemed that Mr. and Mrs. White had decided to take a week’s holiday in York and had not required her presence. In the days that followed, her mood remained subdued. She did not once speak of our school plans, and I suspected she was working herself into a depression or imagined state of ill-health. If Anne had been home, she would have tried to coax her out of such self-imposed misery, but I had long since learned that these moods lifted eventually and of their own accord, requiring no intervention from me. An invitation from Ellen to stay at Brookroyd over Christmas could cure all of Charlotte’s complaints in a moment.

‘I can read for half an hour at most, and only then in full daylight,’ she announced one afternoon, throwing aside a copy of The Lyrical Ballads I’d borrowed from the circulating library in Keighley. ‘If I carry on like this, I shall lose my eyesight altogether!’

‘It’s gloomy today,’ I said. I glanced up from my drawing, a sketch of a blackbird for Martha Brown who was fond of creatures.

‘I have seen so little of the world,’ she said, flicking at the spine of the book. ‘How strange we must seem to God, looking down on us. The earth He gave us stretches in all directions, is full of riches, yet all we do is run around in the same little circles, like poor little mice, scratching an existence.’ Her gaze shifted. Outside, the sky was an impenetrable grey, the rain coming in sullen slaps against the dining room window. ‘Every day the same hills, the same valleys.’

‘The bad weather is passing,’ I said. ‘You’ll feel better by tomorrow. Perhaps we will receive news of our very first pupil.’

‘Emily.’

‘Yes?’

‘I have a different plan.’