Because of the time constraints, you’ll want to make sure that you go about reading the passages in the most efficient way possible. You might also want to use a slightly different approach depending on whether the passage is prose or poetry, but there are a few things you should keep in mind regarding both types of passage.

You are reading in order to answer questions, not for enjoyment or appreciation. As you read, ask yourself, “Do I understand this well enough to answer a multiple-choice question about what it means?”

You can come back to the passage anytime you want, and you should go back to the passage in order to answer the questions.

Both of these points address the same issue. The passages are on a test, but you don’t do most of your reading on tests. Generally when you study for an English test you read the works your teacher assigned and have to answer questions from memory; however, on the AP Literature and Composition Exam, the passages will likely be unfamiliar, which can be a tad daunting. The test writers deliberately select works that aren’t typically taught in schools. The writers are great, familiar authors, but the works are more obscure.

The good news is that it’s unlikely anyone else taking the test has seen the work before either; therefore, you’re all starting with a similar level of knowledge. The best news is this is an open-book test. You don’t have to read the passage in the same way you read for English class. You’re not looking to memorize information —you can use the passage to your advantage while answering the questions. Soak up the basic structure of the passage, but don’t stress over remembering every little detail. Only focus intently on what the questions are asking you, and find the parts of the passages that will help you answer appropriately.

The right way to read prose passages in the multiple-choice section is simple. It’s the method that works for YOU. Bear in mind that this is a timed test, so while we stand by the Active Reading tools provided in Chapter 1, you may want to modify or supplement those skills with the following. As you work through the practice drills and tests, make a point of trying different methods so that you can identify the one that’s most efficient for you. It does you little good to fully understand a passage if that means you only have time to read and answer half the questions.

For some students, a quick reading of the questions provides context. For others, it’s a total waste of time. When you’re practicing on passages, try it each way and see what works best for you. Then, stick to that strategy. What you’ll want to do is read each question and only the question. Don’t read the answer choices. Don’t try to memorize the questions. Just get a sense of what they’re asking you about—questions about literary devices or a certain character, for example. This can provide clues that will make your reading more active.

There are two stances on active reading; one is to identify the main idea of each paragraph before moving on. The other expands upon the idea of previewing questions and suggests that you skim only the first and last sentences of the paragraphs to get an overall sense of what the passage is about. When you go back, either guided by questions or, time permitting, to read the passage (as outlined in the next step), you’ll be less likely to trip up on context. The trade-off is the time you spend doing this.

Just read, without fixating on details, without getting stuck or going blank. When you hit a sentence you don’t understand in a book, you don’t panic, do you? You don’t assume: “I might as well throw this book away…without that sentence it’s just a useless collection of incomplete alphabetical symbols.” When you read normally, you read for the main idea. You read to understand what’s going on. When you hit a tricky sentence, you figure that you’ll be able to make sense of it from what comes later, or that one missing piece of the puzzle isn’t going to keep you from getting the outline of the overall picture. This is exactly how you want to read an AP English Literature and Composition Exam passage.

For the AP English Literature and Composition Exam, main idea means the general point. It is the ten-words-or-fewer summary of the passage. The main idea is the gist, or the big picture. For example, suppose there’s a passage about all the different ways a man is stingy, how he cheats his best friend out of an inheritance, and scrimps on food around the house so badly that his kids go to bed crying from hunger every night. The passage goes on for 50 or 60 lines describing this guy. The main idea is that this guy is an evil, greedy miser. If the passage gives a reason for the miser’s obsession with money, you might include that in your mental picture of the main idea: This guy is an evil, greedy miser because he grew up poor. No doubt the passage tells you exactly how he grew up and where (in an orphanage, let’s say), and exactly what kind of leftover beans he eats (lima) and exactly how many cold leftover lima beans he serves to his starving kids each night (three apiece), but those are details, not the big picture. Use the details to build up to the big picture.

We don’t want you to think that the main idea can be found in some magic “topic sentence.” The writers on the AP Exam are sophisticated; they often don’t use any obvious clues like topic sentences. With poetry passages especially, looking for topic sentences is a waste of time; however, use context clues to make inferences regarding theme and main idea.

Preview the questions. (optional)

Skim.

Read for the main idea.

Ideally, you read a poem several times, ponder, scratch your head, and read some more. Then again, ideally you have your favorite poem by your favorite poet, and all afternoon to read—not 15 minutes with some poem you couldn’t care less about and 15 multiple-choice questions staring you in the face.

It’s a test, so you’ve got to read the poem efficiently, and the key to the process is keeping your mind open, especially the first time through.

It might help to be clear about the difference between a narrative and the kind of poetry you’ll see on the AP Exam. A narrative unfolds and builds on itself. Although one’s understanding of what came earlier in the narrative is deepened and changed by later developments, by and large the work makes sense as it flows; it is meant to be understood “on the run.”

Verse is different. Yes, the way it unfolds is important, but one often doesn’t even grasp that unfolding until the second or third (or ninetieth) read. A poem is like a sculpture; it is meant to be wandered around, looked at from all sides, and finally taken in as a whole. You wouldn’t try to understand a sculpture until you’d seen the whole thing. In the same way, think of your first reading of a poem as a walk around an interesting sculpture. You aren’t trying to interpret. You are just trying to look at the whole thing. Once you’ve seen it, and taken in its dimensions, then you can go back and puzzle it out.

What we’ve just said applies to poetry in general. But how can you apply that to the AP Exam? Here’s the answer: When you approach a poem on the AP Exam, always read it at least twice before you go to the questions.

The first read is to get all the words in your head. Go from top to bottom. Don’t stop at individual lines to figure them out. If everything makes sense, great. If it doesn’t, no problem. The main thing you want is a basic sense of what’s going on. The main thing to avoid is getting a fixed impression of the poem before you’ve even finished it.

The second read should be phrase by phrase. Focus on understanding what you read in the simplest way possible. This is when you should look for the main idea.

Don’t worry about symbols. Don’t worry about deeper meanings. The questions will direct you toward those aspects of the poem. You will need to go back and read parts of it, perhaps the entire thing, several more times, but only as is necessary to answer individual questions. To prepare yourself for the questions, all you need is a general sense of what the poem says and to get that understanding you need only the literal sense of the lines. We can’t emphasize this point enough: Keep it simple.

Don’t panic if you can’t seem to grasp an understanding of the poem. Many people are probably struggling and completely baffled by the same poem. Don’t skip the passage. Look for questions that take you to specific line item details (In lines 56–60…”) and attempt to answer those questions using the specific lines of poetry. POE is your friend here! Don’t obsess over the poem or the answers. Do your best to provide an answer using POE, but if you really get stuck, don’t dwell. Choose an answer (maybe your LOTD) and move on.

Good poetry makes conscious use of all language’s resources. By pushing the limits of language, poetry creates a heightened awareness in the reader. Poets sometimes use uncommon vocabulary, odd figures of speech, and unusual combinations of words in strange orders; they play with time and stretch the connections we see between ideas. All of these essential resources can make poetry seem difficult, but it’s not impossible. One important thing to remember is that many poems are open to a myriad of valid interpretations. It’s not your job to have a meaningful experience when reading poetry on a test; it’s your job to read for language resources and main ideas that will help you to answers the questions correctly.

You can connect to a poem in many ways, but you aren’t reading for a nice, meditative experience on the AP Exam: you’re reading to answer the questions correctly. The following things are what you’re looking to identify and analyze as you read:

Punctuation use

Diction (word choice)

Imagery

Theme/main idea

Figurative language (metaphors, similes, synecdoche)

The secret to understanding AP poetry passages quickly and fully is to simply ignore the “poetry parts.” Ignore the rhythm, ignore the music of the language, and above all, ignore the form. This means you should do the following:

Ignore line breaks.

Read in sentences, not in lines. Emphasize punctuation.

Ignore rhyme and rhyme scheme.

Be prepared for “long” thoughts—ideas that develop over several lines.

When approaching poetry, many students tend to do the opposite of what we suggest here: they emphasize lines and line breaks and totally ignore sentence punctuation.

True, sometimes there’s no problem: When lines break at natural pauses and each line has a packet of meaning complete in itself (these are termed end-stopped lines), the poem becomes easier to read.

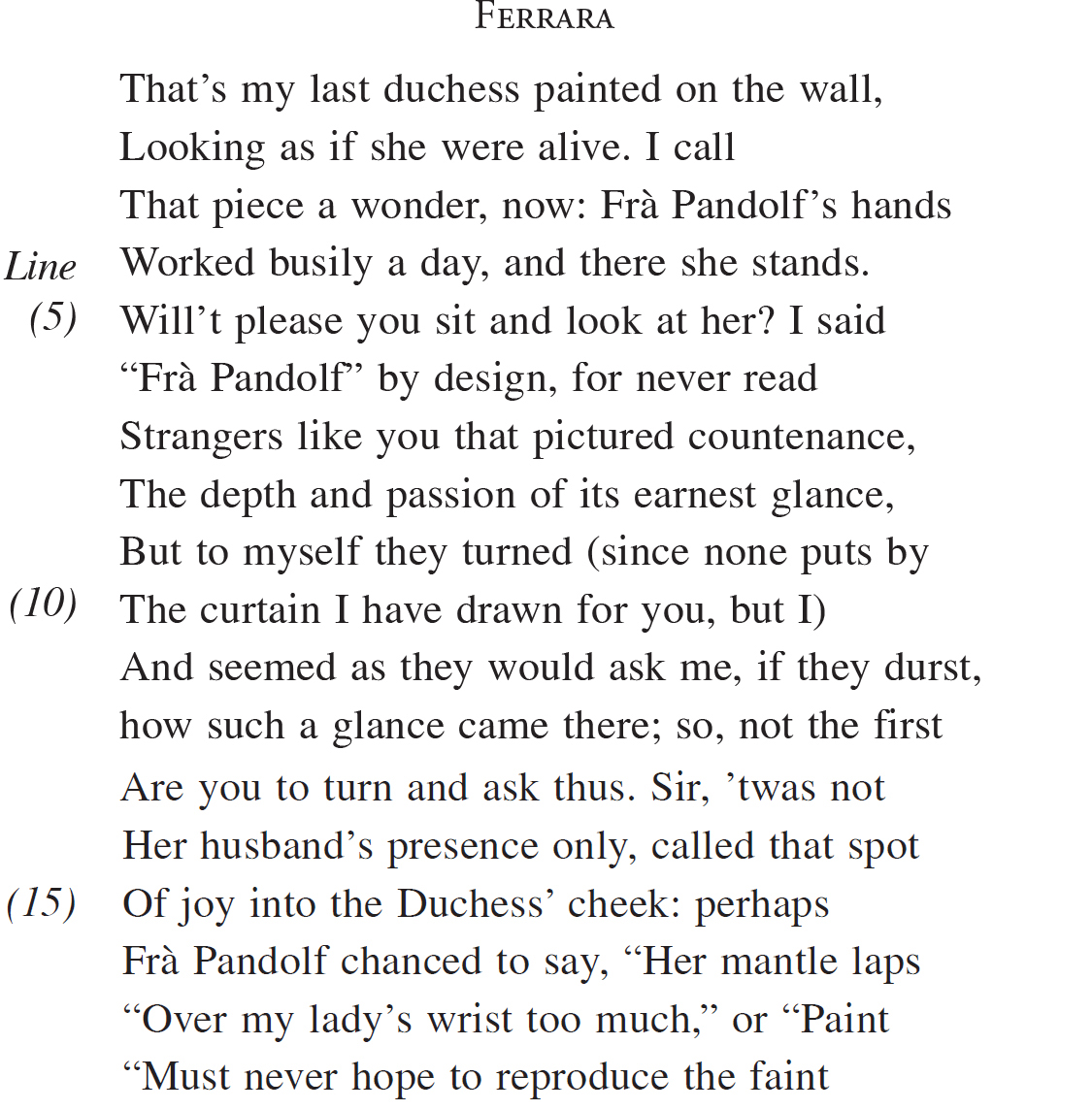

Consider the next selection. It’s the first 13 or so lines of “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning. This is the kind of poetry you can expect to find on the AP Exam, but it is unlikely that you would see a poem that is this well known.

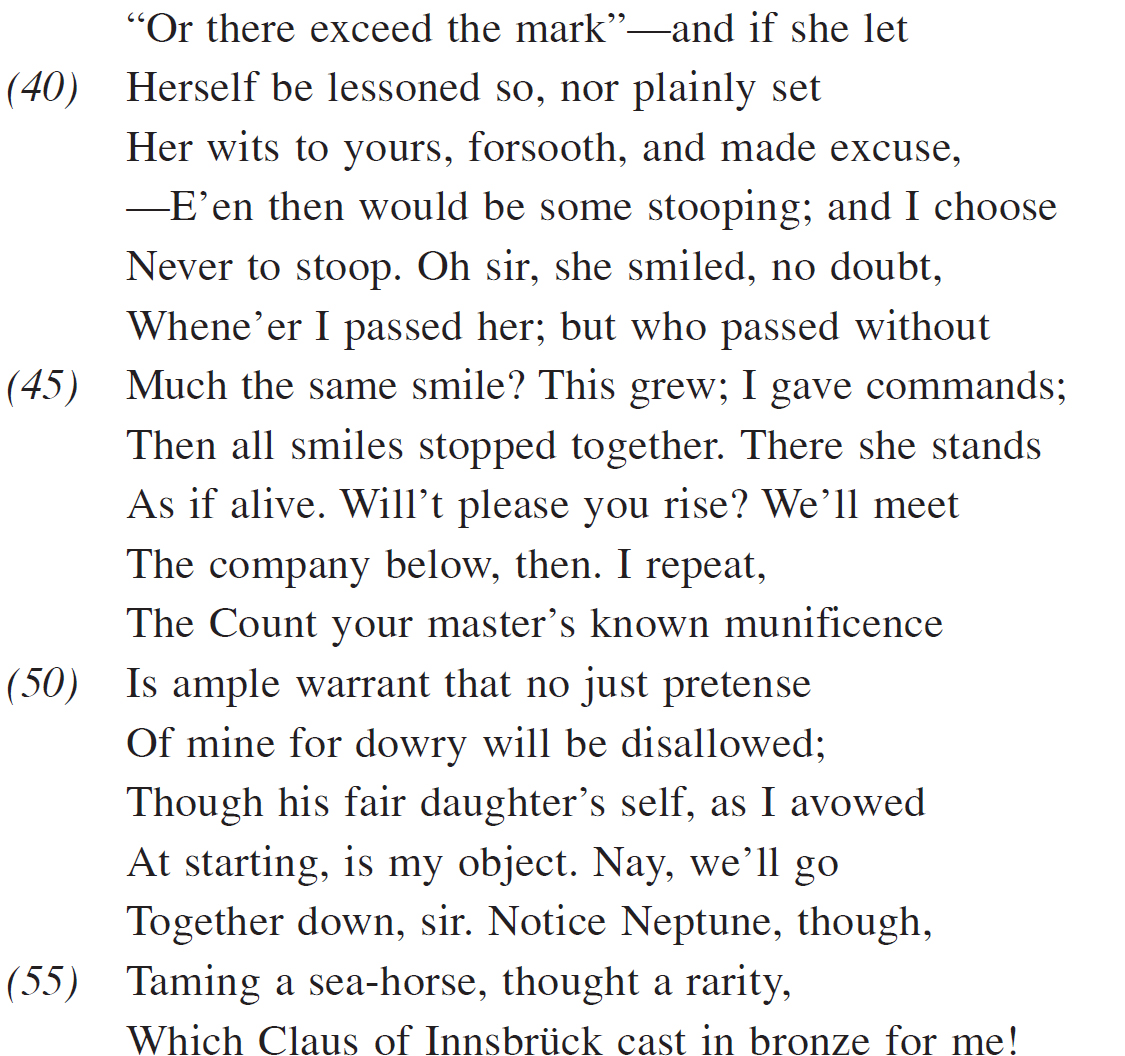

The poem is a monologue spoken by a nobleman, the Duke of Ferrara, to a representative of the Count of Tyrol. Ferrara seeks to take the wealthy count’s daughter for his bride and is in the midst of discussing the arrangement with the count’s representative. When Ferrara speaks of his “last duchess,” he refers to his first wife, who has quite recently died at the age of 17 under mysterious circumstances. The implication is that Ferrara has had his first wife murdered, an implication the poem brings home with understated menace.

You won’t be given this kind of information on the test, but with practice, you should be able to figure out many of the aspects of the poem by yourself. For example, the first two lines of the poem (which is printed below in sections) give a careful reader some important information. The speaker of the poem is a duke, as he is talking about his “last duchess.” He is standing in front of a painting of this woman who is no longer alive. All of this information, if assimilated readily and with an eye toward tone and the big picture, will help you answer questions, even if the questions don’t ask specifically who the speaker is or whether the duchess is alive.

This poem is challenging, but it’s not impossible with the right reading strategies. Remember: you’re supposed to come into the test with a plan! The first few lines are relatively straightforward: The Duke points to the painting, remarks on its lifelike quality, mentions the artist (Frà Pandolf), and invites his listener to sit and contemplate the portrait for a moment. Although lines 3–4, “Frà Pandolf’s hands/Worked busily a day” are distinctly unmodern speech and might give some folks a moment’s pause, there are signposts to help guide readers. Even if you don’t know that “Frà” is used as a title of address to an Italian monk (and who does?), you can still figure out the big picture of this poem.

Then comes the remainder of the passage, beginning from line 5, “I said/‘Frà Pandolf’ by design, for never read” and the trouble begins. Now, the truth is that what is written there is easy enough that if you can break the habit of placing too much emphasis on line breaks, you can read it as prose. Browning has deliberately written his verse so that the lines break against the flow of the punctuation. If you expect little parcels of complete meaning at every break, you’ll end up lost. Let’s consider the troubling part written as prose:

“I said ‘Frà Pandolf’ by design, for never read strangers like you that pictured countenance, the depth and passion of its earnest glance, but to myself they turned (since none puts by the curtain I have drawn for you, but I) and seemed as they would ask me, if they durst, how such a glance came there.”

This is just one long sentence, broken by parenthetical asides, in which the duke says, “I said ‘Frà Pandolf’ on purpose because strangers never see that portrait (or its expression of depth and passion) without turning to me (because nobody sees the portrait unless I’m here to pull aside the curtain) and looking at me as though they want to ask, if they dare, ‘How did that expression get there?’”

Read the poem as prose and you’ll see it’s pretty easy. If you have trouble doing this, try putting brackets around each sentence.

Now if you’re really alert, you’ll notice that the Duke still hasn’t exactly explained why he mentioned Frà Pandolf on purpose. He eventually does (in his sideways fashion), but if you read poetry without being ready for long thoughts that develop over several lines, you’re going to read “I said, ‘Frà Pandolf’ by design, for never…” and expect the explanation—pronto. When it doesn’t come you think you’re lost, and once you think you’re lost, you are. How is “that pictured countenance” an explanation of why he said “Frà Pandolf?” It isn’t, and it never will be, but you can spend hours trying to come up with reasons why it is.

Don’t get the wrong impression. Browning isn’t easy reading. But you’ll find that if you follow our suggestions for reading poetry, you can cut to the heart of what Browning and poets like him are saying. Ignore line breaks and instead pay close attention to punctuation and sentence structure. Be ready for “long” thoughts that develop over several lines or even stanzas. You’ll still find the poems on the AP Exam challenging for a variety of reasons: because of their vocabulary, because of their compression of a great deal of information into just a few lines, and because of their often complicated and unusual sentence structure.

If you read poetry the way we suggest, however, you’ll find that you can still use the context of what you do understand to answer questions.

Here’s Browning’s “My Last Duchess” in complete form. Read it according to our advice and see what you can get from it. (Many discussions of this famous poem exist online, and you can read a few in order to compare what you’ve figured out with what others have said about it.)

Look at these lines from Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”:

Now fades the glimmering landscape on the sight,

And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,

And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds.

Read this passage aloud, and you can’t help but stop on the line endings even if there were no commas. The lines build, one upon the next, shaping a picture as they combine to form a mildly complex sentence. The ease with which these lines can be read stems from the fact that each line contains only complete thoughts; there are no loose ends trailing from line to line. This is “nice” poetry; that is, it’s nice to you. Each line ends on a natural pause that lets you gather your thoughts. Each line holds something like a complete thought with very little run-over into the next line. Although the stanza is written in one sentence, it easily could have been written in four separate sentences:

The landscape fades.

The air is still.

The beetle wheels and drones.

The tinklings [of bells worn by livestock] lull the folds.*

*Folds are enclosures where sheep graze, or the flocks of sheep themselves.

This paraphrase is lousy poetry, but it gets the main idea across. If the poetry you see on the AP Exam reads like the example above, great. But if you think every poem should be like that stanza or if you try to make every poem read like that one, you’re headed for trouble. The poetry on the AP Exam is likely to be more challenging.

You are reading in order to answer the questions—that’s the whole point.

Reading for a test is different from normal reading. You have limited time, and you have to approach the passages in a way that takes that restriction into account.

You can reread the passage (or parts of it) anytime you want, and you should go back to the passage in order to answer the questions.

Preview the questions if it helps you.

Skim the passage.

Skimming should never take more than a minute.

Read for the main idea.

Preview the questions if it helps you.

On the exam, read the poem twice before you answer the questions.

The first read is to get all the words in your head.

The main thing you want is a basic sense of what’s going on.

Try not to get a fixed impression of the poem before you’ve even finished it.

The second read should be done phrase by phrase. Focus on understanding what you read in the simplest way possible. Don’t worry about symbols. Don’t worry about deeper meanings. Try to visualize what you’re reading as you follow the narration of the poem. Also try reading the poem as you would read prose. (See “Poetry into Prose” below.)

You will need to go back and read parts of the poem—perhaps the entire poem—several more times, but only as necessary for your work on individual questions.

Find the spine—the prose meaning—of the poem.

Ignore line breaks.

Emphasize punctuation. Read in sentences, not in lines.

Be prepared for “long” thoughts: ideas that develop over several lines.

Before you read a poem as poetry, read it as prose.