Once you’ve finished working a passage using active reading techniques, you need to answer the questions. If you’ve paid attention so far, you already know you’re going to answer all of the questions, using your Letter of the Day to guess when you aren’t sure of the answer. You should also know by now that you must approach the test efficiently, making the most of your time in order to get the best possible score.

In order to answer the questions efficiently, you’ll need to be able to recognize two main types of questions:

general comprehension questions that concern the prose selection or poem as a whole

detail questions that focus on one part of the passage

and three question formats:

Standard

EXCEPT/LEAST/NOT

Roman numeral

General comprehension questions ask about the overall passage. These questions don’t send you back to any specific line(s) or paragraph(s) in the passage.

Here are some examples of general comprehension questions.

The passage is primarily concerned with…

Which one of the following choices best describes the tone of the passage?

Which one of the following choices best describes the narrator’s relationship to her mother?

How does the author’s use of irony contribute to the effect of the poem?

To whom does the speaker of the poem address his speech?

It is evident in the passage that the author feels her home town is…

As these examples show, a general comprehension question can target either the passage as a whole, as the first question about theme (main point) does, or it can focus on one aspect of the entire passage, as the second question about tone does. In either case, the scope of the question covers the whole passage from beginning to end. If (in the third question) the narrator’s relationship to her mother sounds harmonious in the first couple of lines but is revealed as adversarial throughout the rest of the passage, then “adversarial” is the answer that “best describes” the relationship. You need to consider the overall impression given by the whole passage.

General comprehension questions will often ask about the following:

The theme (main point) or author’s purpose. What is the author writing about? Why? What does the author intend for readers to think or feel or believe or do after they finish reading?

The tone. What is the author’s (or the narrator’s) overall attitude toward the subject of the passage? Is he or she critical? Approving? Neutral? Is the author being humorous, satirical, ironic or deadly serious? Is he or she skeptical or a believer? And—very important—how do you know what the author’s attitude is?

The style. Here you’re looking for diction (word choice), syntax (sentence choice) and literary devices—in other words, how the author conveys the theme and purpose. Is the vocabulary sophisticated or something that almost all readers could understand? Are the sentence structures varied (a mix of simple and complex, loose and periodic)? Does the author rely on literary devices (such as allusions, repetition, and symbols) to convey the theme, or is the delivery straightforward?

The structure. How does the narrative progress? Do events occur in chronological order? Is the progression interrupted by flashbacks or flashforwards or dream sequences? When are the main characters introduced? When do major points in the plot occur? Are two similar plots being developed in parallel? Is there a sudden change (perhaps in emphasis or tone) part of the way through? Why? How are the different pieces connected and—very important—why did the author choose to connect them in this way?

The point of view. Does the author use a first-person narrator (“I”) whose personality, background, and biases act as a filter through which events are described? Or is the narrator an objective, camera-type recorder of events? What impact does the type of narrator have on the passage?

The development. How does the plot develop? What techniques does the author use in order to develop a character? How does the author develop the main point?

Detail questions almost always send you back to specific places in the passage. They tell you where to look and ask something about a particular segment or even a specific word.

Always read at least one sentence or line before and after the place indicated in the question, so you’ll have the correct context.

Here are some examples of detail questions.

What significant change occurs in the speaker’s attitude toward the countryside in lines 5–9?

How do the final words of the third paragraph, “but then, I should have known better than to trust him,” alter the remainder of the passage?

In lines 1–5, the phrase “This loaf’s big” is used as a metaphor for

The poet’s use of the word “sublime” (line 21) suggests that

What does the pond in the first paragraph symbolize?

Which of the following is the best paraphrase for the sentence that begins at line 9?

If you’re having trouble grasping the overall theme of a passage or the author’s purpose, the specific questions are a good place to start. You’ll learn more about the passage with each one you answer, and the whole passage just might fall into place.

The most common question format on the exam, standard format questions have a straightforward question stem, followed by five answer choices. Here are some examples of standard format question stems:

The metaphor “fountain of delight” in paragraph 2 has the effect of

The dream described in lines 30–32 suggests that

The author’s attitude towards his subject could be characterized as

Even though the test writers put EXCEPT, LEAST or NOT in capital letters, you could still miss those crucial words if you’re just racing through the question stems instead of reading them carefully, word for word. In essence, these three qualifiers invert the answer you’d normally be looking for in a standard format question. Consider these examples:

Ludwig seems to value all of the following characteristics in a business partner EXCEPT

Which of the following characteristics does Ludwig consider the LEAST important in a business partner?

Ludwig is NOT looking for which of these characteristics in a business partner?

Which four characteristics does the passage say Ludwig wants to see in a business partner? Those four will be in the answer choices. But those aren’t what you’re looking for. You want the one characteristic he does NOT consider important, or considers the LEAST important, or is the EXCEPTion to what he thinks is important.

To tackle these tricky questions, disregard the EXCEPT, LEAST or NOT; cross them out. You’ll be left with a standard format question:

Ludwig seems to value [which of] the following characteristics in a business partner EXCEPT

Which of the following characteristics does Ludwig consider the LEAST important in a business partner?

Ludwig is NOT looking for which of these characteristics in a business partner?

Now eliminate any choice that would be a correct answer for your new, Standard format question. The remaining choice will be the correct answer for the EXCEPT/LEAST/NOT version of the question.

These are two-part questions, but they’re not as time-consuming as they seem if you approach them correctly.

Think of a Roman numeral question as a standard format question with only three answer choices: I, II and III. However, unlike standard format questions, Roman numeral questions can have more than one correct choice among the three offered. Deciding which one(s) is or are correct will automatically give you the answer to the five lettered choices that follow.

Let’s work through an example.

The description of the farm in lines 13–21 implies that the speaker

I. had a happy childhood there

II. regrets returning to the place where he grew up

III. hates his present life in the city

(A) I only

(B) I and II only

(C) I and III only

(D) II and III only

(E) I, II, and III

Assume the description of the farm is positive and nostalgic. That would eliminate choice II: the speaker is probably glad to return to a place of happy memories. So right away you can eliminate any lettered choice that includes II: (B), (D) and (E). Now you’re left with (A) and (C). If the speaker had a happy childhood on the farm (I), you could infer that he might well hate his present life in the very different city environment (III). Which lettered choice includes both I and III? That’s (C) and the correct answer.

There are usually three or four questions on basic grammar. That’s one grammar question or fewer per passage, so grammar is not a big deal on the multiple-choice section. The samples we provide in Chapters 7 and 8 should give you a good idea of what the grammar questions are like. Because there are so few grammar questions, we don’t recommend you spend a lot of time studying grammar. You’d be far better off working on writing timed essays or reading poetry.

Here’s a great simple sentence to memorize for basic grammatical relations:

Sam threw the orange to Irene.

It isn’t poetry, but this sentence clearly shows the basic grammatical relationships you need to concern yourself with on the AP Exam.

Sam is the subject.

The orange is the direct object.

Irene is the indirect object.

Notice that in this sentence, the direct object is in fact an object (an orange). The orange is thrown to Irene, the indirect object. In other words, the indirect object receives the direct object. The concept is pretty simple.

There are two more sentence elements you should understand: the phrase and the clause. Here’s a model sentence that should help you keep clear on their definitions.

Feeling generous, Sam threw the orange to Irene, who tried to catch it.

The heart of the sentence is still Sam threw the orange to Irene, as subject, verb, direct object, and indirect object all remain the same. But we’ve added a phrase to the beginning of the sentence and a dependent (also called subordinate) clause to the end. Both phrases and dependent clauses function as modifiers. Feeling generous (a phrase) modifies Sam; and who tried to catch it (a clause) modifies Irene.

The difference between clauses and phrases is simple:

A clause has both a subject and a verb.

A phrase does not have both a subject and a verb.

Because a clause has both a subject and verb, a clause is always close to being a sentence of its own. The dependent clause, who tried to catch it, could be turned into a complete sentence by replacing who with Irene or she, or adding a question mark at the end.

The hallmark of a phrase is its lack of a subject or verb (or both). Phrases obviously cannot stand alone. Feeling generous needs the addition of both a subject (Sam) and a verb (was) in order to become the sentence Sam was feeling generous.

Our model sentence contains another clause besides the dependent clause we’ve already mentioned. The other clause is Sam threw the orange to Irene. Because it has both a subject and a verb, it must be a clause. Notice that it doesn’t need any changes in order to stand alone as a complete sentence: that makes it an independent clause.

Grammar is one of those things that helps with just about everything else, from comprehension of a tricky sentence to linking up parallel ideas and identifying structure. But specific questions about grammar basically boil down to things like whether you know what an antecedent is. Because there are so few grammar questions on this test, it’s better to focus on the active reading and POE skills that will help you get through the other questions.

You can complete the questions in any order you like, but that doesn’t mean you should jump around and do them in any old order. After you finish reading a passage, but before you begin answering the questions, ask yourself, “Do I feel confident about this passage? Would I be able to explain this to a friend? Could I explain its main idea?”

The answer to this question determines the order in which you should tackle the test questions.

If you feel confident about your comprehension of the passage, complete the questions in the order they are given to you. Don’t worry about the order of the questions; you’re in good shape.

If you don’t feel confident about the main idea, do the detail questions first.

The reasoning behind this ordering method is simple. The main idea is the crucial thing to get from a reading passage, whether prose or poetry. When you have the main idea nailed down, you aren’t likely to miss more than a few questions on the passage. Knowing the main idea will help you answer all of the other general questions and many of the specific questions as well.

When you don’t feel confident about the main idea (which usually means the passage is pretty confusing), you want to start with the specific questions because they tell you exactly where to go and also give you something on which to focus.

As you reread the lines toward which the specific questions point you, you should become more and more familiar with the passage. Often after doing a specific question or two, the meaning of the passage “clicks” for you, and you will get what’s going on. Don’t answer the general questions until you have a firm sense of the main idea. If, after answering all the specific questions, you still don’t really know what the point of the passage is, give the general questions your best shot and move on.

The main idea should be your guiding rule for most of the questions on any passage. We call this principle Consistency of Answers. As you work on a passage you will find that the best answer on several of the questions has to do with the main idea. The rule: When in doubt, pick an answer that agrees with the main idea.

Pick answers that agree with each other. You’ll also find that correct answers tend to be consistent. It’s a simple idea that comes in very handy. For example, if you’re sure the correct answer to question 9 is (B), and (B) says that Mr. Buffalo is extremely hairy, you can be sure that question 10’s Mr. Buffalo isn’t bald. Correct answers agree with each other.

The best way to understand how to use this very effective technique is to see it at work. You’ll see plenty of examples in the following chapters; we’ll discuss this technique in detail when we work on actual questions.

First things first: Don’t leave any questions blank! There is no guessing penalty: Worst-case scenario, guess blindly. But guessing smartly is much better! POE is an acronym for Process of Elimination. You are probably already acquainted with POE in its simplest form: cross out the answers that you know are wrong. The Cracking the System approach to POE isn’t really different, just more intense.

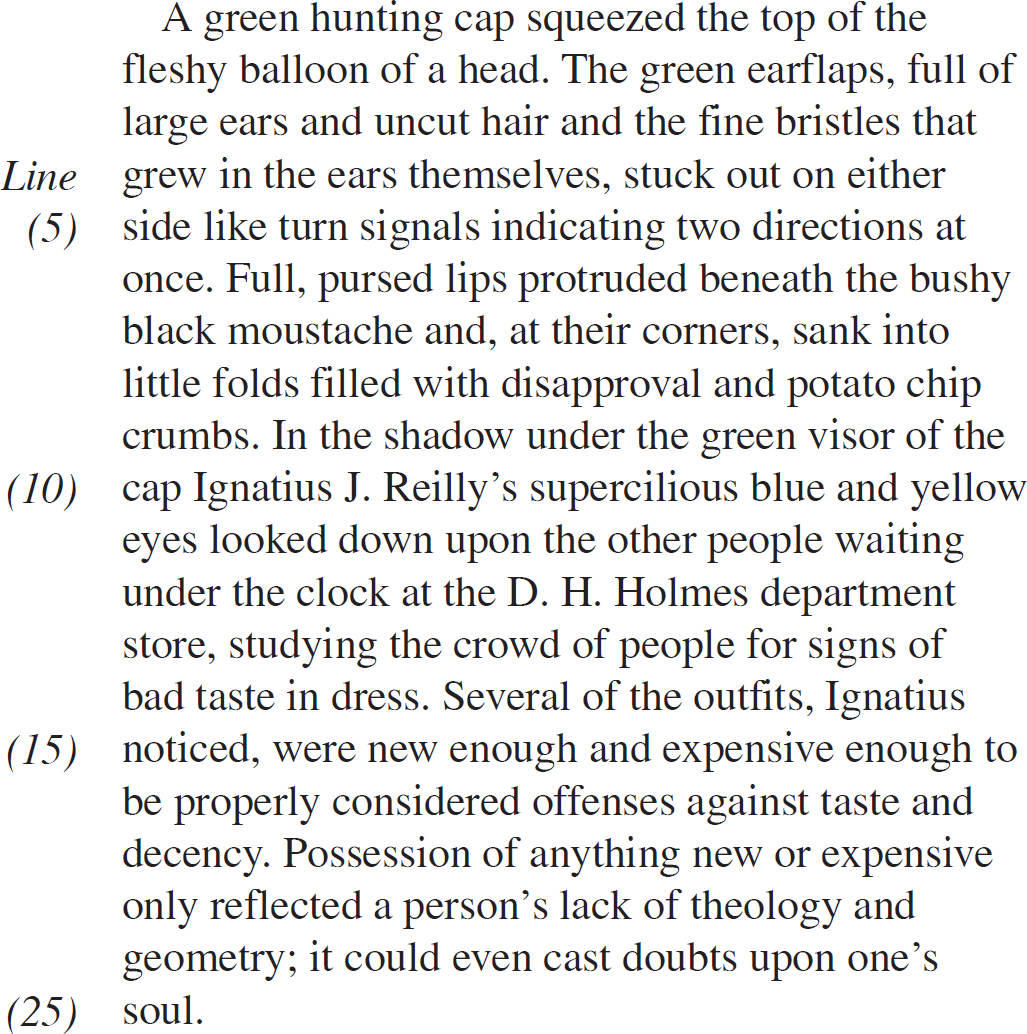

There are always two ways to answer a multiple-choice question correctly. The first is to have the answer in mind right from the moment you read the question. If you understand the passage and the question, you’ll often see the best answer among the choices. Far more often, however, you’ll be slightly (or not-so-slightly) unsure. The test writers are pretty good at spotting places in a text where students are likely to have trouble, and they tend to write questions about these spots. The test writers are also pretty good at writing wrong answers that are quite appealing. Before you doubt yourself, however, make sure you have read the question carefully. It’s possible to understand the passage but misread a question. The extra second or two you devote to reading the question may increase the number of questions you answer correctly. Still, no matter how strong a reader you are, some questions will cause you to have doubts about the answer. That’s when you use The Princeton Review-style POE. What does that mean? It means: Stop looking for the right answer—look for wrong answers and eliminate them. Let’s look at the same example we used on this page, from John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces.

1. Lines 6–9 of the passage best describe the author’s portrayal of Ignatius J. Reilly as

(A) a sympathetic portrait of an effete snob

(B) a comically ironic treatment of a social misfit

(C) a harshly condemnatory portrait of a bon vivant

(D) an admiring portrait of a great hunter

(E) a farcical treatment of an overly sensitive man

This is a typical AP English Lit question. It asks for an evaluation of a passage for comprehension. The majority of the questions take this form. In the example above you’ve been asked, essentially, “What’s going on in lines 6–9?” The actual passage would have been longer (usually around 55 lines), and the rest of the passage would certainly help you understand this section by putting it in context, but nevertheless, there is enough here to answer the question.

If you don’t immediately spot the best answer, use POE. Go to each choice and say, “Why is this wrong?” You can look back at the explanations on pages 60–61 to check your thinking.

Recognize the basic categories of questions.

General Comprehension

Detail

Don’t worry about grammar for the AP English Literature and Composition Exam. It isn’t worth enough points to cause perspiration.

Do it your way.

If you know the main idea, answer the questions in order.

If you’re uncomfortable with the main idea, answer detail and factual questions first.

Use Consistency of Answers.

When in doubt, pick an answer that agrees with the main idea.

Pick answers that agree with each other.

Guess aggressively as needed using POE.