We’re going to take you through our AP English writing process, one we’ve designed specifically for AP essays. The most stressful part of writing essays under time pressure is coming up with something to say quickly. In this chapter we’ll show you how to get the ideas that give you something to write about in the first place. We aren’t going to teach you how to write; you’ve already spent years learning to write. However, AP essays are unlike anything you’ve had to write before and you probably haven’t spent years learning how to write them.

Approximately 90 percent of this chapter is about how to get an overall idea of your essay and create a great first paragraph. If you can get off to a good start, you’re more than halfway to a great score.

Just as with the multiple-choice section, you want to have a common sense, step-by-step approach to the essay section (and know how to use it). Here it is:

Bring a watch and note the time. Remember: 40 minutes per essay.

Pick the essay (prose, poetry, open) you want to write.

Identify the key words in the essay prompt.

Skim the passage.

Work the passage, make notes, and identify quotations you will want to use.

Use the Idea Machine (explained in this chapter) to plan your first paragraph.

Support and develop the points you made in your first paragraph in your body paragraphs.

Get a solid conclusion on the page. Your conclusion can be as important as your introduction, and it usually is.

Repeat the process with the other essays.

You don’t have time to write an outline. Outlines are for organizing longer, more complex pieces of writing, like research papers, when you have the time to revise and plan. We know you’ve probably had outlining drummed into you by your teachers. But short essays, like the ones you’ll write for the AP Exam, don’t call for an outline. You don’t even have time to rewrite. Our method shows you how to come up with a solid beginning from which you can build so that you can just write the rest of the essay without an outline.

We’ve developed a method of approaching AP essays that we call the “Idea Machine.” Hey, don’t get us wrong, the real idea machine is in your skull. The point here is to focus your brain, imagination, and analytical skills in a way that’s productive for the AP Exam. This approach won’t let you down. Use it, and your essays will shine.

The Idea Machine is a series of questions that direct your reading to the material needed to write an essay. Take these questions, apply their answers to the essay question, and in the end you’ll find you’ve written the kind of essay the Readers want to see.

The Idea Machine

What is the meaning of the work?

What is the literal, face-value meaning of the work?

What feeling (or feelings) does the work evoke?

How does the author get that meaning across?

What are the important images in the work and what do those images suggest?

What specific words or short phrases produce the strongest feelings?

What elements are in opposition?

That may not look like much, but when we put all the pieces together in this chapter and the next you’ll see just how powerful of a tool we’re giving you.

Whether you are working on a prose or poetry passage, there is a classic essay question that you will be asked to address. Here it is in its most basic form:

Read the following work carefully. Then, write a well-organized essay in which you discuss the manner in which the author conveys ideas and meaning. Discuss the techniques the author uses to make this passage effective. Avoid summary.

The classic essay question actually breaks down into three questions. The first two should look familiar because they’re part of the Idea Machine.

What does the poem or passage mean?

How did the author get you to see that?

How do the answers to question 1 and 2 direct your knowledge to adequately answer the question?

The first question is hidden, but totally important. It’s the foundation on which you build the rest of your essay. Your (high-scoring) essay should answer those three questions in that order. Question 2 is the one you’ll be asked on the exam; the test writers feel that question 1 is implied.

If the first question is “What does the passage or poem mean?” Well…what does that mean? What is meaning?

For the AP essays, the meaning of a work of prose or poetry is the most basic, flat, literal sense of what is said plus the emotions and passions behind that sense.

The passages and poems they ask you to write about on the AP English Literature and Composition Exam will present some event or situation in the same way a newspaper article presents an event or a situation. But AP essay passages will, of course, do more than that. They will make the event or situation “come alive” by bringing in human emotions and passions in such a way that those emotions and passions are as important as the facts.

Let’s consider an example:

Think of how much will be lost by the newspaper version. Will they really let us know the degree of Oedipus’ suffering, his sense of terrible, yet undeserved guilt? Of course not, but those emotions are parts of what the story means, and are the most important part of your essay.

When we say the first question is, “What does the poem or passage mean?” We want you to answer two simple things:

What is the basic literal sense of the poem or passage (the newspaper version)?

What emotions are involved both for the characters in the story and for you, the reader?

The combination of the answers to these questions is the meaning.

You must absolutely avoid talking only about the newspaper version. Doing that amounts to a summary, something the AP Readers do not want. Discuss the way emotions are involved in the story and focus on the feelings the language produces, and you’ll be discussing meaning in the right way. Always identify point of view, tone, and figurative language usage. Discussing these literary elements will ensure that you are moving beyond a summary.

Your AP Exam may well have the classic question on it almost word for word, but probably not. What you will likely see is a modified classic essay question. There is an endless number of modifications for the test writers to throw at you. For example, the question might ask you to discuss “the narrator’s attitude toward the nature of war,” “the speaker’s attitude toward society,” or “the author’s use of repetition.”

Of course, the specifics mentioned in the essay prompt are what you should pay close attention to when you read. Just as in the multiple-choice section, where looking at the questions can help you read the passages more actively, identifying precisely what the Readers want you to write about can help you focus on those aspects of the poem or prose.

However, even if you’re responding to a modified essay prompt, you should begin just as if you’re answering the classic one. You want to talk about what meaning you found in the poem or passage, and then use that as a foundation to discuss the topic about which the question specifically asks.

Let’s look at an example. (You don’t need the actual passage to understand our discussion of the question here.)

Read the following passage carefully. Write a well-organized essay that discusses the interrelationship of humor, pity, and horror in the passage.

This seems like a simple enough question—until you try to answer it. How do you go about discussing the interrelationship of humor, pity, and horror? Most students start out something like this:

The story X by writer Z mixes humor pity and horror in an interesting way. It begins with a father meeting his son. The father seems like a funny guy because of things he does, but then we see that he is actually a person who arouses our pity because he goes too far, so far in fact, that the father becomes almost horrible.

The student who writes this response knows he’s basically flailing. He’s just trying to answer the question without looking foolish. If the student uses reasonable examples, writes with some organization and only a few grammatical errors, then the student will get a 5, a “limbo” score—not passing, but not failing.

On the other hand, the student who understands that this question is a modified form of the classic question and knows how to use the Idea Machine will break it down.

What does the passage mean? What was I supposed to get from it? What did I get from it? Okay, I got that the passage was about a father and son and that the son feels his father is basically embarrassing. Yeah, that sounds about right. Now, let’s see, how does the author get that across using humor, pity, and horror?

Notice how this student has taken the question, turned it into the classic question, and simply used the modification to focus on the point to be developed. The student began by describing the meaning of the story. (“The son feels his father is basically embarrassing” is the meaning. Remember the meaning doesn’t have to be complicated.) Then this student asked herself, How does the author get that across using humor, pity, and horror? This student’s opening is going to look something like this:

In story X, writer Z shows us a son confronted by the embarrassing spectacle of his father. By shifting the son’s perspective of his father from humor and pity, to horror, we see and feel the son’s fluctuating, uncertain responses to his father’s vulgarity and ignorance.

This student is writing about something and it shows. She’s on the way to a score of at least 7, and if the essay stays this clear and focused, it’s going to earn a score of 9. Do you see how slight an alteration has been made between this response and the one that came before it? Yet there’s a world of difference. The first student rephrased the question without really saying anything, and then began to work his way through the points, ticking them off…first humor, then pity, then horror. The second student began by answering the implied question in every essay: What does this story mean? Then she began to show how the author brought that meaning across.

The best part is that the second essay is easier to write than the first one. It’s easier to write an essay about something than nothing. Writing a bogus essay is like trying to wind up a ball of string with nothing to wrap it around. The second essay is going to wrap itself neatly around the core of the story’s meaning—the son’s uncertain embarrassment at his father’s behavior.

Sometimes the questions can be fairly intimidating, but don’t let them throw you. Remember to use the Idea Machine. What does the passage mean? How does that meaning come across?

Once you’ve got that under your belt you can think about how to focus on the points in a question about a poem. Let’s look at an example:

Read the poem below carefully. Notice that the poem is divided into two stanzas and that the second stanza reapplies much of the first stanza’s imagery. Write a well-organized essay in which you discuss how the author’s use of language, including his use of repetition, reflects the content and tone of the poem.

You should look at the question and remember that it’s just a modified version of the classic essay question. Ask yourself “What is the meaning?” and “How do I know it?,” then you can think about how the author uses imagery to convey that meaning. In fact, this question almost organizes itself once you break it down. Your first paragraph should talk about what you get from the whole poem, and your subsequent paragraphs should discuss the language and meaning of each stanza. Your conclusion should look at the poem as an entire piece and reiterate your emphasis about why and how repetition is important in understanding the overall tone and theme of the poem.

The key to a great essay is a great start and the key to a great start is having an overall idea of what you’re doing. We’ve shown you how to address the meaning (literal and emotional) of the poem right from the beginning, and that you must then address the “how” of the author’s method. Taken together, these things will form your opening and the central idea around which you will write—the idea you will explain and support. If you’re already a sharp, sensitive reader, following these instructions will lead you to high-scoring essays.

Sounds easy in principle. But are you ready? Let’s go back to that tough, intimidating question we just looked at in the No Fear section, this time along with the poem that goes with it. We’ll use our approach to come up with a good first paragraph for a high-scoring essay. Then we’ll show you two powerful tools you can use to open up a passage and get the kinds of ideas that blow AP Readers away.

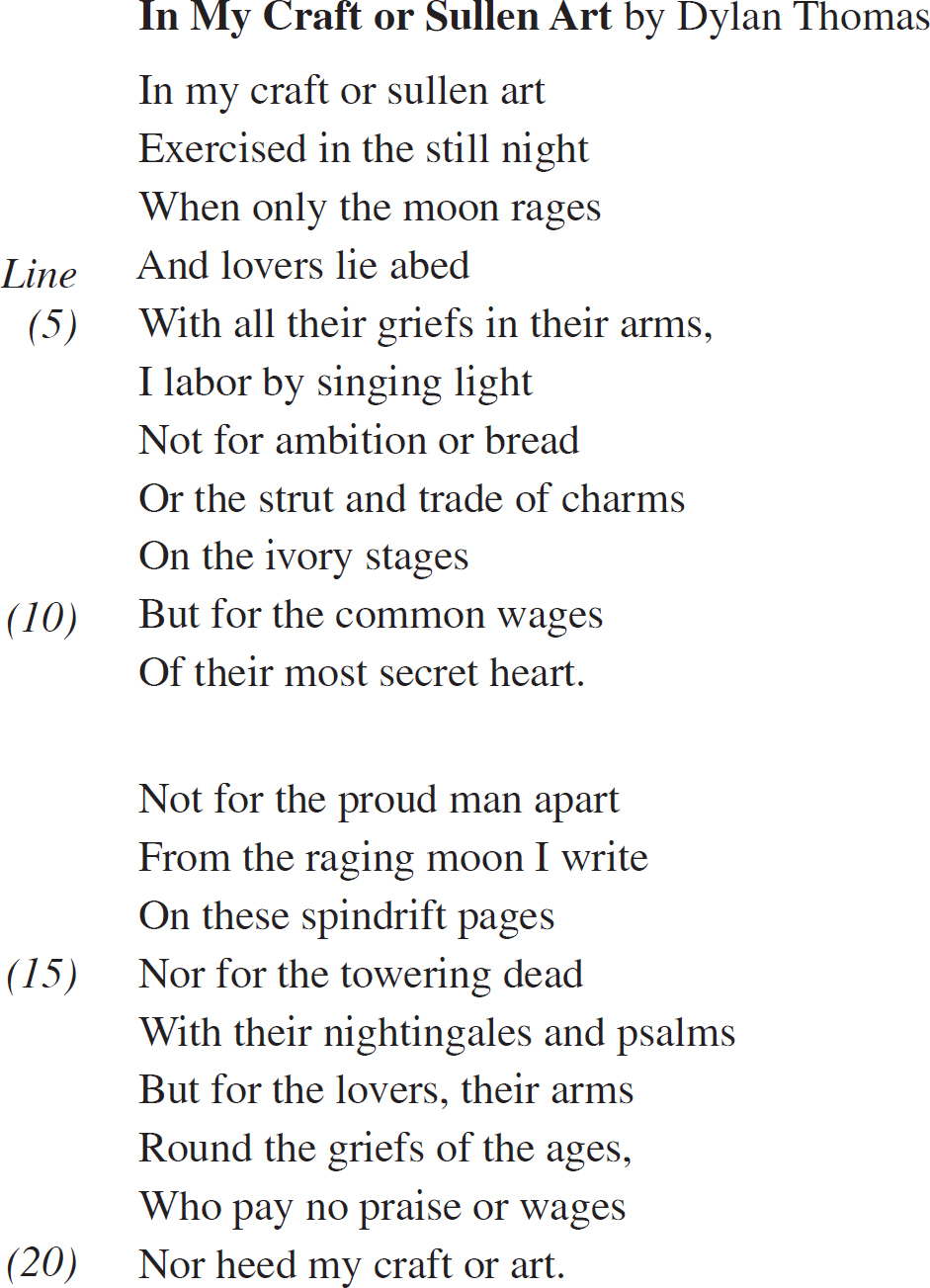

Read the following poem carefully. Notice that the poem is divided into two stanzas and that the second stanza reapplies much of the first stanza’s imagery. Write a well-organized essay in which you discuss how the author’s use of language, including his use of repetition, reflects the content and tone of the poem.

So, where do you begin? Well, before you begin to consider the repetition mentioned in the essay instructions, get the answers to the questions that let you write a classic essay. Use the Idea Machine.

What does the poem say, literally? That shouldn’t be too tough to answer, even if you don’t know exactly what Dylan Thomas is trying to say. Put it in your own words. What does the poet say about his “craft or sullen art”? Take a moment to think about it, then read on.

You should have come up with something like this: “Dylan Thomas explains that he isn’t writing for money or fame but for lovers who don’t even care about his writing.”

Okay, now what is the feel of the poem? What emotions are conveyed? Is there an overall emotion? Again, think about it a moment before you read on.

It’s a tougher question, isn’t it? You probably went back to the poem to look at it again, thinking, “Just what emotion was I supposed to get? There’s something there, but what?”

You might have picked up on a few aspects of the tone: pride, grief, loneliness, perhaps futility, and also perhaps the opposite of futility—a sense of total purpose. The poem has a truly complex emotional range in it. Don’t let that scare you off; it only gives you more to write about.

What is the meaning of the poem for your AP essay? Take your literal sense and your emotional sense, and combine them:

Dylan Thomas’s “In My Craft or Sullen Art” explores the pride, grief, loneliness, futility, and yet sense of total purpose that come from the author’s struggle to write not for fame or for wealth but for “the lovers, their arms round the griefs of ages.”

So far so good. But don’t think we’re finished. This sentence is just the answer to question 1 of the Idea Machine—what does the poem mean? If you’re particularly astute, you may even notice that we haven’t completely answered that question. We’ve only said what Thomas “explores.” We haven’t come out and taken a stand on exactly where Thomas’s exploration has led him. Don’t worry. You don’t have to try and pin everything down all at once. If this essay were an assignment due at the end of the week you’d want to write a rough draft that you could revise carefully later. Here on the AP Exam, you don’t have the opportunity for careful revision. You don’t have to write a perfect essay. The Readers don’t expect you to, not even for a score of 9. Just stay with our method: What does the work mean, how does the author achieve his effects, and what does the question ask you to address?

Now you have the second part of our three-part approach to consider:

How does the author achieve his effects? Perhaps in answering that question we can take more of a stand. How does Thomas bring his emotions into his sense of what writing means to him and (because the essay instructions demand we consider it) what does the repetition have to do with it?

How indeed? Thomas gets his message across in so compact a fashion that you may feel a little lost and overwhelmed. Remember, you’re just trying to write a 40-minute essay on a poem you’ve never seen before. The Readers don’t expect perfection or profound originality. They want to see you focus on saying something, and then say it as clearly as you can. In brief, they want to see you confidently develop your ideas as best you can.

Here’s how we’d complete our opening statement and answer the question of how Thomas explores his sense of what, to him, it means to write:

Dylan Thomas’s “In My Craft or Sullen Art” explores the pride, grief, loneliness, futility, and yet sense of total purpose that come from the author’s struggle to write not for fame or for wealth but for “the lovers, their arms round the griefs of ages.” Thomas gives us an image of himself, laboring alone “by singing light” and contrasts this with an image of self-contained completeness, of lovers wrapped in each other’s arms, oblivious to all the world and even to his poetry. By repeating these images, and key words like “moon,” “rage,” and “grief,” he emphasizes the power of his emotions and the intensity of his need to define himself and the purpose of his art.

This opening puts our essay off to a great start. Of course, you might have had different ideas, and you undoubtedly would have phrased your ideas another way, even if you saw exactly what we saw in the poem. You might even have written two or three better sentences—although you wouldn’t have had to in order to score well. This brings up our next point.

Many other insights about Dylan Thomas’s poem are waiting between the lines. It all depends on what you got from it. If you ask yourself, “How can I describe the subject of this poem in one word?” You will find that your answer, in this case, reflects the title of the poem. It is his writing. Then, ask yourself: “What is Dylan Thomas saying about the craft of writing?” The answer to this question is the theme of the poem. If you look at the last few lines of the poem, you will discover the answer in those lines. Usually if you look at the title of the poem, the last few lines of the poem, and combine that with the one word that accurately describes the subject of the poem, you are on your way to accurately describing the theme of the poem. You want to make sure that you are on track with your interpretation because the Readers want to see that you have understood the point of the poem and can explain how this understanding helps you answer the essay question.

Use that literary vocabulary you’ve been building by studying the glossary. The Readers are paying attention to your craft of writing as you address the question. They want to see how the literary work you’ve been asked to write about acted on your imagination and how well you’ve managed to convey the impressions you’ve received.

Speaking of imagination, notice what we’ve done in the “how” part of our opening paragraph about the Dylan Thomas poem. We’ve discussed imagery. We chose to mention the contrasting images of the author working alone and of the lovers in their self-enclosed togetherness. You might have chosen something else but the point to remember is: It’s always a safe bet to talk about imagery.

In writing (as opposed to cinema or theater or painting) an image is made of words. Is that obvious? Yes, it is. But just because it’s obvious doesn’t mean all students pay attention to that important fact. On the AP essays your job is to discuss writing. Remember then that whenever you’re discussing the imagery in a passage, you’re discussing words. If a word sticks out as unusual or particularly vivid, think about it. Ask yourself, why did the author use that word? What effect does that word have? If you can think of something to say about the words an author has used to create an image and the specific effect those words have, by all means put it in your essay. You’ll have the AP Readers eating out of your hand. One easy method of discussing imagery is to try to create a short film clip with your words based on what the poet has written.

Notice that in our sample opening we zeroed in on the two most striking word choices in the poem. Rage and grief. It’s odd (and poetic) to say lovers have their arms around their griefs. And when was the last time you saw the moon raging? A lot of students run from unusual language like that. They think that the poet is just being a typical crazy artist who can’t really be understood or that they’ll misinterpret the phrase anyway and look dumb. But when you see unusual usages like that, consider them. Why that word? What does that word do to the feel of the piece? Thinking this way will jog ideas loose and come up with the material that makes for great AP essays. Notice also that both rage and grief have strong emotional content. Writing about the emotional content is the best way to let the Reader know you’re really reading and not simply enacting some dry, mechanical exercise.

If you’ve been following our discussion so far, you should see that you need to be able to pull ideas from the text you’re working with so that you have ideas for your essay. Considering imagery and word choice is a good start, but there’s one more concept we want you to think about as you read, something that should really help you find the ideas that you need to write a great essay.

How can you get to the heart of what you read on the AP English Literature and Composition Exam? How can you find something interesting and important to say about a passage quickly? What do you look for to see what makes a passage or a poem “tick”?

The answer is opposition.

Attune your reading to seeing opposition and you’ll open up AP passages like cans of sardines. You’ll have something around which to center your discussion of the way an author uses language and imagery and tone to make her point. If you carefully read the question, you will notice that there is usually a comparison or contrast that it directs you to address. Sometimes it is subtle, but sometimes you are directed to focus your answer on a comparison or contrast noted within the passage or two passages.

Opposition vs. Conflict

Some people call opposition conflict, but we think that’s too narrow a term. Conflict sounds like two people having a fight. Don’t be crude. Be subtle. Opposition is everywhere in good writing, and the passages on the AP Exam will always be good sources. Seek it out as you read because opposition leads you to the important parts of a passage or poem.

Opposition occurs when any pair of elements contrast sharply. Another way to think about opposition is tension—think of the two opposing elements as if they were magnetized poles, attracting and repelling each other. Opposition provides a structure underneath the surface of the poem, which you will unlock by discovering the oppositional elements. Opposition might be as blatant as night and day. Or it might be less obvious: a character who’s naïve and a character who’s sophisticated. Opposition might be found in a story that begins with a scene in a parlor but ends with a scene around a campfire, which would be the opposition of indoors and outdoors. It would be easy to miss if you weren’t looking for it but it can often be found between the author’s style and his subject. For example, a cerebral, intellectual style that’s heavy on analysis in a story about a hog farmer would be opposition. Your essay would want to address why the author wrote that way and what effect it has on the story. Keep an eye out for any elements that are in contrast to each other as they’ll often lead you to the heart of the story.

Let’s look at that Dylan Thomas poem again. Notice what we went after in our opening paragraph: the image of the author working alone and the image of lovers in each other’s arms. That’s an opposition. Do you see how it’s not exactly a conflict? It’s a pairing of images whereby each becomes more striking and informative when placed against the other. Doesn’t that pair of images seem central to the poem? Doesn’t it seem there’s something to talk about there? What it means exactly is open to interpretation, and that’s exactly what you should do when you see elements opposed to each other: interpret. Don’t worry about getting it right; there is no single right answer. The AP Reader will see that your searching intelligence has found the complexity of the material and is making sense of it. That’s exactly what the Reader wants you to do. (And it’s what very few students attempt to do.)

Opposition creates tension and mystery. What’s the most mysterious line in “In My Craft or Sullen Art”? We think it’s “And lovers lie abed/With all their griefs in their arms.” That line alone has an opposition: If they’re lovers, why do they have their griefs in their arms?

So your job is to figure out what Thomas means by that. The answer: Nothing simple, but something you can write about. Realize that you don’t have to resolve opposition. You don’t have to interpret that line (or the poem) in a concrete way that makes absolute perfect sense. It’s a poem, not a riddle.

Our opening paragraph mentioned a third opposition: Thomas’s sense of futility and his sense of total purpose. The sense of futility in the poem comes from the statements that the lovers “pay no praise or wages,” nor do they heed Thomas’s “craft or art.” Describing how Thomas gets across his deep sense of purpose is more difficult even though it is the stronger of the two impressions. In many ways the entire poem is about conveying the sense of purpose Thomas feels when writing poetry.

We found these things because we looked for the oppositions. Some oppositions are obvious. Like a tiger in a bus station, they catch your attention immediately and make you wonder what’s going on. Good writers boldly toss together mismatched concepts, objects, and tones all the time. But good writers also work with quiet oppositions that aren’t nearly so easy to spot. If you aren’t paying attention, you’ll feel what’s going on without realizing where it’s coming from. Many literary oppositions come from within one character. The character who wants two totally opposite things at the same time is a classic case of opposition, as is the character who badly wants something that he just isn’t cut out for. Another important opposition is tone. Some writers will write about the silliest thing possible in a deadly serious way. (This is generally done to make a situation funnier.) Still another opposition, one that is often handled with supreme delicacy and with seemingly infinite repercussions, is time. Writers will often let the past stand in opposition to the present. The story of a once proud family that has fallen on hard times is an example of a plot that uses the changes time brings to develop oppositions.

We could come up with hundreds of specific examples of oppositions in literature but those examples won’t do you any good if you haven’t read the works referred to. Our point here is to give you a tool with which to generate ideas for your AP essays.

You’re probably still a little unclear as to how to apply this concept of oppositions to a short AP essay, but don’t worry. The samples and examples in Chapter 10 will take you through several AP passages and point out how you might use oppositions to find ideas (while also boosting your essay scores into the 8’s and 9’s).

Looking back at our overall approach to the Essay section, you’ll see that the second to last point is the recommendation to do an essay check. That sounds fancy, but all it means is that you should think briefly about the points you need to make in your essay.

The time to do this thinking is after you’ve written that first paragraph. The first paragraph comes from using the Idea Machine: discussing the meaning of the passage or poem (remember, the newspaper version plus emotion) and beginning to talk about how the author gets her point across. This method gives you a first paragraph that establishes the foundation on which the rest of your essay will be built. If it’s hyperfocused, it will already set out the overall points you intend to cover, but even if it just gives you a general platform on which to build, you’ve got plenty, enough to put you miles ahead of the majority of other (flailing) students. The essay check is just a spot check, a place to pause, make sure you’re on the right track, and haven’t forgotten anything important. When you finish your first paragraph, stop and ask yourself the following questions:

What points does my first paragraph indicate I’m going to cover?

Do those points address the specifics the essay question calls for?

In what order am I going to put my points?

When you’ve decided the order in which to put your points, get back to writing. Your check shouldn’t take more than a minute. The least important part of the check is deciding the order of your points. It’s the closest thing to an outline you need to do, but don’t overdo it. As long as you’ve paused to think about addressing the question it makes sense to form a rough plan of how you’ll proceed. But the idea is to make it easier for you to write, not to suffocate your writing. Be flexible. If it’s convenient to change the order of your points as you write, change them. If you think of new things to say, say them!

As you write, you’ll notice things that you hadn’t seen at first, things that will depart from your original ideas and take you in unexpected directions. Should you include these things? YES!

Many, many students are intimidated by the test. They think their writing has to be truly organized and tight and end up writing short, dry, little essays: Essays that receive a score of 5. Go with the flow. As long as your ideas have some connection to the question that was asked, include them. Write a great first paragraph that sets you out in the right direction and then loosen up—you’ll score high.

Once you’ve finished your first paragraph and your essay check, it’s time to develop your essay. When it comes to development, each essay is unique. The best way to study development is through examples. The next chapter is devoted to sample essays; we’ll show you how to put our method (and your ideas) into practice.

If you can get off to a good start, you’re more than halfway to a great score.

Use our approach:

Note the time. Remember, 40 minutes per essay.

Pick the essay (prose, poetry, open) you want to write.

Identify the key words in the essay prompt.

Skim the passage.

Work the passage, making notes and identifying quotations you will want to use.

Use the Idea Machine to plan your first paragraph.

Support and develop the points you made in your first paragraph in your body paragraphs.

Get a solid conclusion on the page.

Repeat the process with the other essays.

Don’t write an outline.

Identify key words in the prompt.

Understand the question and how to turn the question into an essay idea.

There is a basic format for the classic essay question on the exam:

Read the following work carefully. Then write a well-organized essay in which you discuss the manner in which the author conveys ideas and meaning. Discuss the techniques the author uses to make this passage effective. Avoid simple summary.

You probably won’t see the classic question word for word; you’ll see a modified version that asks you to focus on a specific element or two from the passage.

Use the Idea Machine:

What is the meaning of the work? Meaning is literal meaning plus the emotions the work evokes.

How does the author get that meaning across?

important images

specific words or short phrases

opposition

The Idea Machine is the tool that will help you apply your skills specifically to a 40-minute essay.

Any student who can write an adequate essay can write an AP essay that scores a 7 or higher.

Don’t worry about being wrong. Have confidence in your interpretation.

Unusual language and imagery are great places to find essay ideas.

Opposition is created when any pair of elements in a story or poem contrast sharply or subtly.

Look for elements that are in opposition. They’ll lead you to the heart of the passage and give you material for the kinds of ideas that make AP Readers give out nines.

Go with the flow. It is impossible to write a tight, well-organized essay in 40 minutes. Write a great first paragraph that sets you out in the right direction, and then loosen up. Don’t digress, however, and start talking about irrelevant topics. Always stay focused on the text.

Respond to the following questions:

Of which AP essay-writing strategies discussed in this chapter do you feel you have achieved sufficient mastery to write high-scoring essays?

On which AP essay-writing strategies discussed in this chapter do you feel you need more work before you can write high-scoring essays?

What parts of this chapter are you going to re-review?

Will you seek further help, outside of this book (such as from a teacher, tutor, or AP Students), on any of the content in this chapter—and, if so, on what content?