Click here to download the PDF.

Section I

The Exam

AP ® English Literature and Composition Exam

SECTION I: Multiple-Choice Questions

DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOKLET UNTIL YOU ARE TOLD TO DO SO.

At a Glance

Total Time

1 hour

Number of Questions

55

Percent of Total Grade

45%

Writing Instrument

Pencil required

Instructions

Section I of this examination contains 55 multiple-choice questions. Fill in only the ovals for numbers 1 through 55 on your answer sheet.

Indicate all of your answers to the multiple-choice questions on the answer sheet. No credit will be given for anything written in this exam booklet, but you may use the booklet for notes or scratch work. After you have decided which of the suggested answers is best, completely fill in the corresponding oval on the answer sheet. Give only one answer to each question. If you change an answer, be sure that the previous mark is erased completely. Here is a sample question and answer.

Sample Question

Chicago is a

(A) state

(B) city

(C) country

(D) continent

(E) village

Sample Answer

Use your time effectively, working as quickly as you can without losing accuracy. Do not spend too much time on any one question. Go on to other questions and come back to the ones you have not answered if you have time. It is not expected that everyone will know the answers to all the multiple-choice questions.

About Guessing

Many candidates wonder whether or not to guess the answers to questions about which they are not certain. Multiple choice scores are based on the number of questions answered correctly. Points are not deducted for incorrect answers, and no points are awarded for unanswered questions. Because points are not deducted for incorrect answers, you are encouraged to answer all multiple-choice questions. On any questions you do not know the answer to, you should eliminate as many choices as you can, and then select the best answer among the remaining choices.

ENGLISH LITERATURE AND COMPOSITION

SECTION I

Time—1 hour

Directions: This section consists of selections from literary works and questions on their content, form, and style. After reading each passage or poem, choose the best answer to each question and then fill in the corresponding oval.

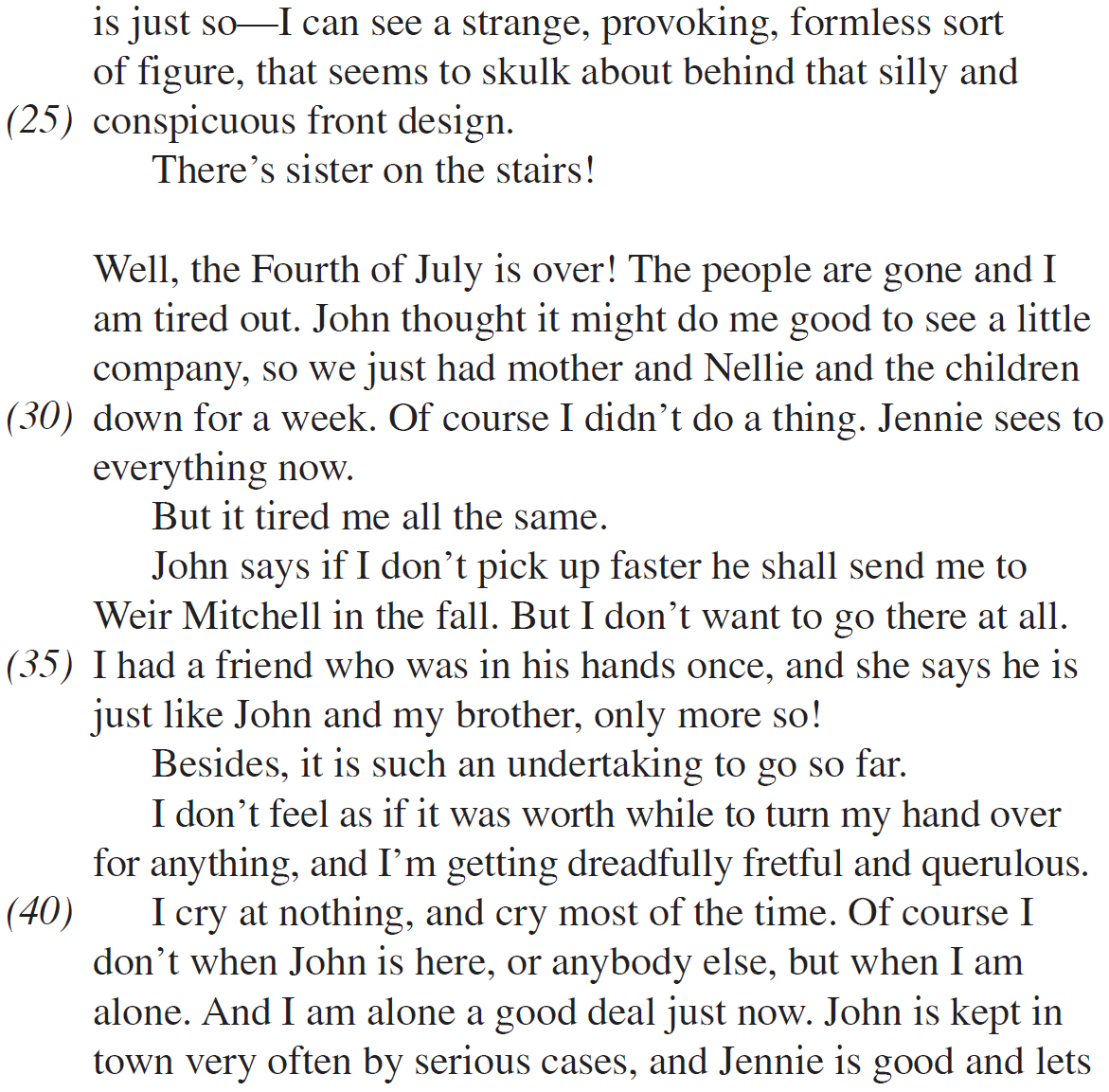

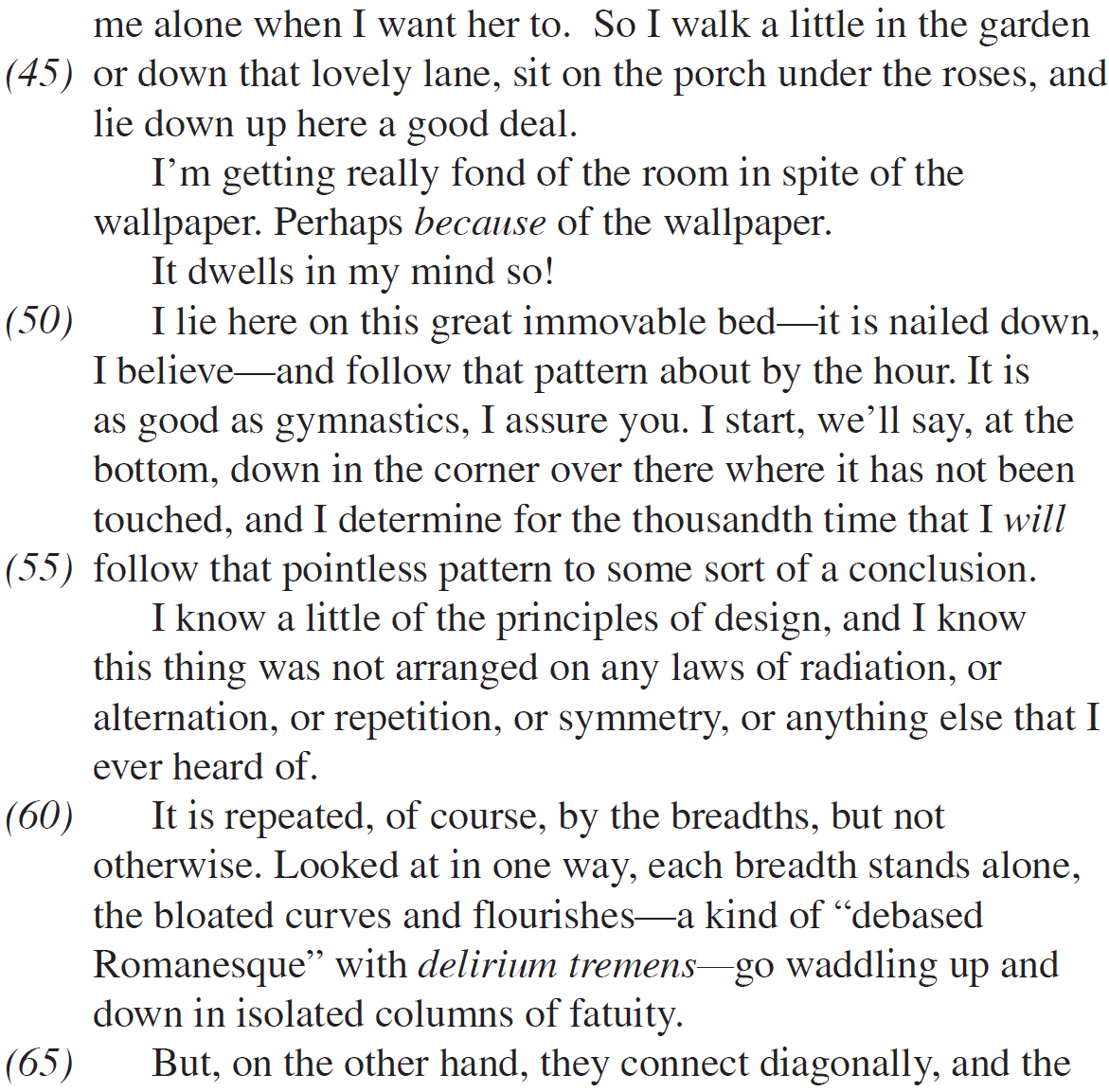

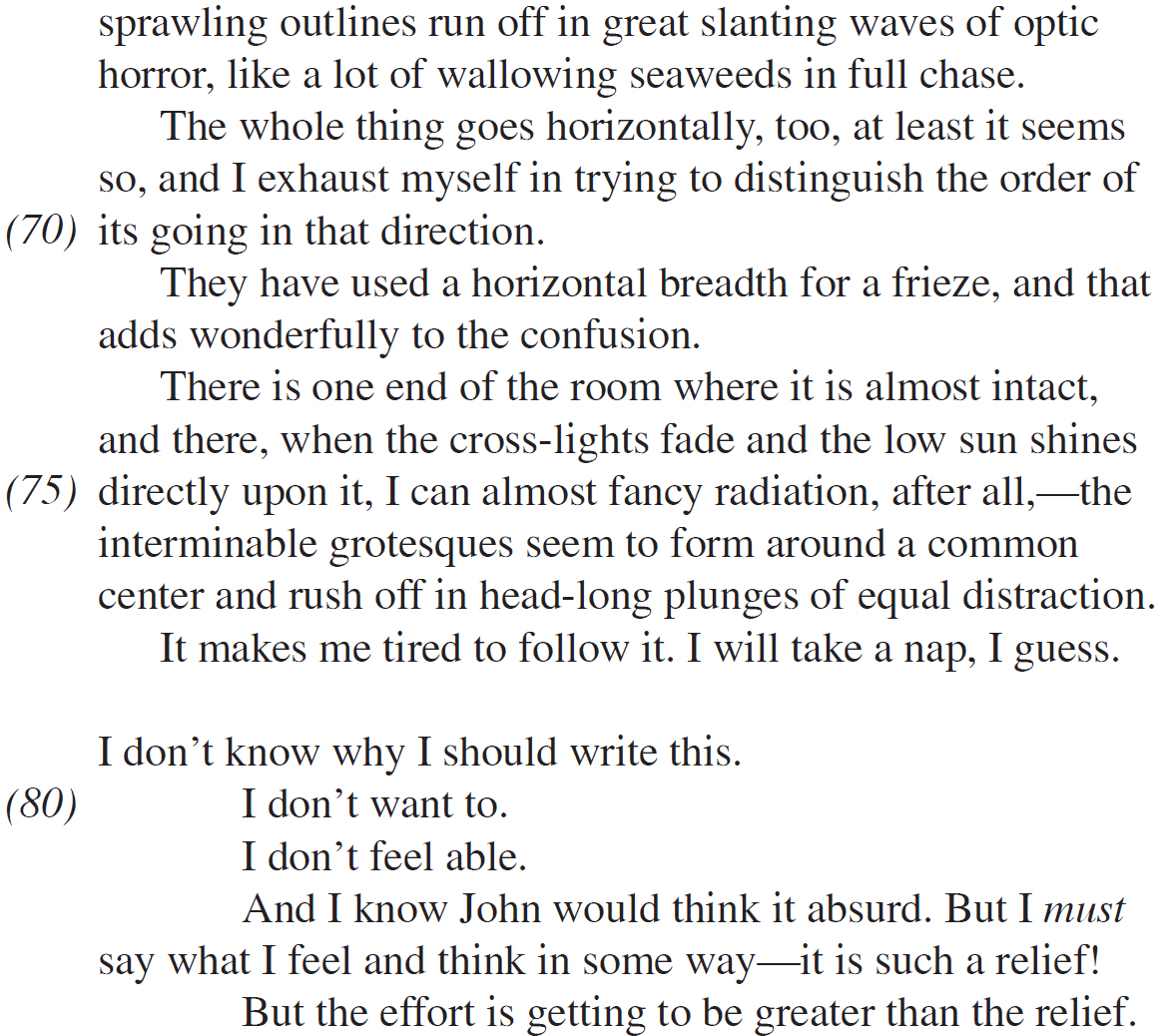

Questions 1–15 . Choose your answers to questions 1–15 based on a careful reading of the following passage.

1. In the first paragraph, preachers are accused of all the following EXCEPT

(A) plagiarism

(B) stupidity

(C) dullness

(D) eloquence

(E) laziness

2. “Saturnist” (line 8) means

(A) astrologer

(B) nymphomaniac

(C) depressed and depressing person

(D) pagan

(E) foolishly optimistic person

3. What are “divines” (line 5)?

(A) Preachers

(B) Great writers

(C) Dead writers

(D) Fools

(E) Saturnists

4. “New herrings, new!” (line 21)

(A) refers to an implied comparison between the writers of new poems and the sellers of fresh fish

(B) suggests that poetry is slippery and hard to catch the meaning of, like fish

(C) implies that poetry is just another commodity

(D) implies that poetry grows stale rapidly, like fish

(E) compares poetry to rotten fish

5. In lines 29–34 London is described as

(A) flooded

(B) a damp, rainy city

(C) the main influence on the English language

(D) a cultural garden

(E) an important port city

6. The main idea of lines 34–40 is which of the following?

(A) People are motivated by concern for their reputations.

(B) Poetry is fair to the virtuous and the evil alike.

(C) Poetry is inspirational.

(D) Poetry is most attractive to atheists.

(E) Poets are very judgmental.

7. Who is Salustius (line 43)?

(A) A French poet

(B) Sidney’s nom de plume

(C) The Roman god of poetry

(D) The King of England

(E) The Wife of Bath

8. As it is referred to in line 49, what is Bath?

(A) A state of sin

(B) A character in Chaucer

(C) A married man

(D) A poet

(E) A town and spa in England

9. In the last paragraph, poets are said to be like

(A) lawyers

(B) mayors

(C) chronographers

(D) townsmen

(E) angels

10. Line 9 is an example of

(A) metaphor

(B) onomatopoeia

(C) paradox

(D) alliteration

(E) apostrophe

11. In line 2, what is the referent of “those”?

(A) Poets

(B) The author

(C) Ballads

(D) Poems

(E) Poetry’s enemies

12. Lines 18–23 argue that

(A) poets must take second jobs to make a living

(B) most people don’t respect poets

(C) there are too many poets

(D) poets have to work hard to present consistently fresh material

(E) poetry books are never bestsellers

13. The author complains (lines 10–11) that the preachers have no eloquence to hold their audience but only

(A) repetition

(B) nonsense

(C) lies

(D) irrelevance

(E) sermons

14. According to the passage, which of the following is NOT a function of poetry?

(A) To encourage the virtuous

(B) To purify the language

(C) To embarrass the villainous

(D) To illustrate and beautify

(E) To plagiarize sermons

15. Who first raised the issue of necessity of poetry to the state?

(A) Nashe

(B) Sidney

(C) Salustius

(D) Plato

(E) Milton

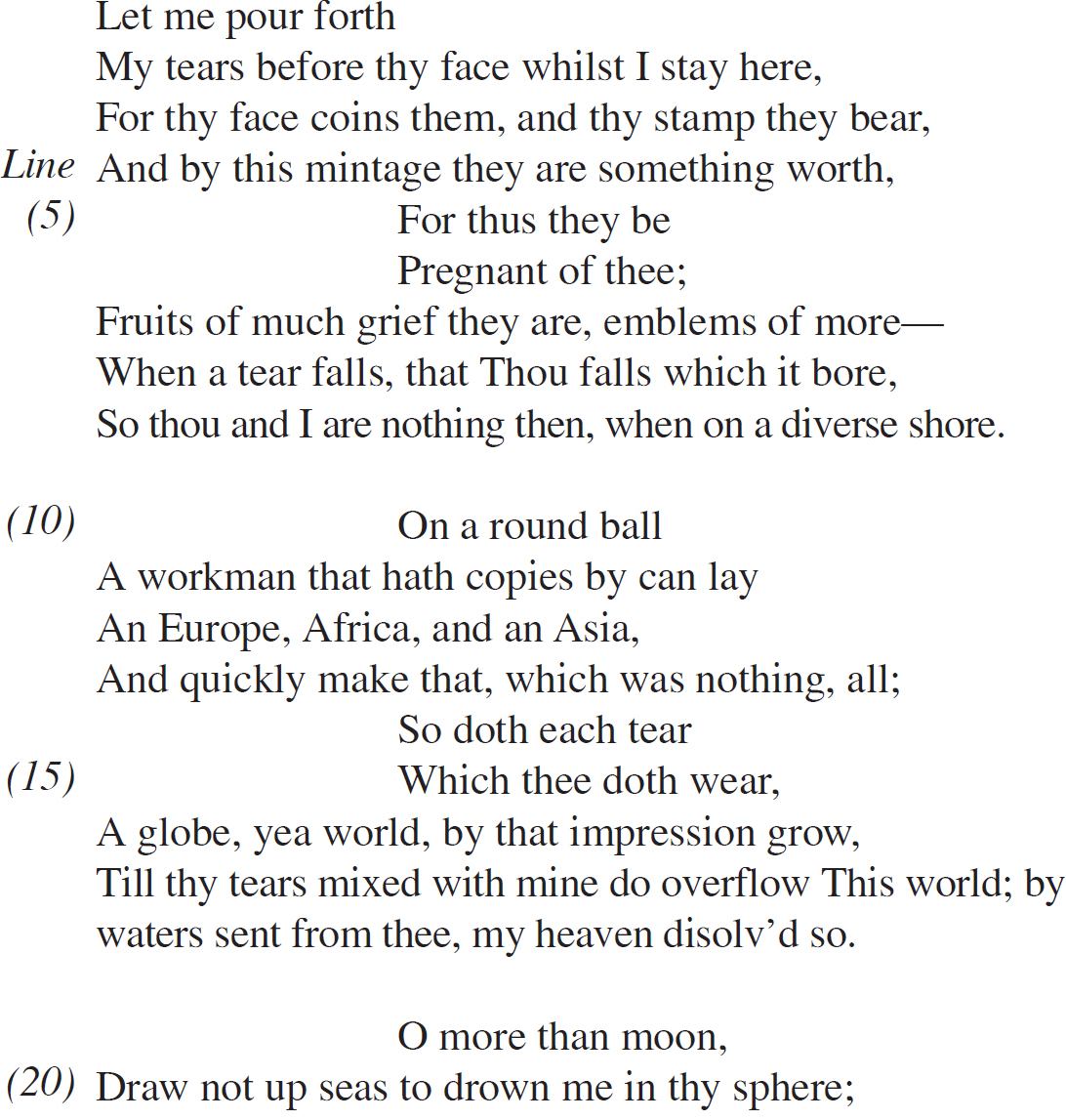

Questions 16–28 . Choose answers to questions 16–28 based on a careful reading of the following poem by John Donne.

16. The situation described in this poem is

(A) the end of a romantic relationship

(B) death

(C) the separation of lovers

(D) the end of the world

(E) a pleasure cruise

17. Lines 10–16 are an example of

(A) paradox

(B) dramatic irony

(C) metaphor

(D) metaphysical conceit

(E) dramatic monologue

19. To what do lines 14 and 15 refer?

I. The speaker’s tears which reflect the beloved

II. The beloved’s tears

III. The beloved’s clothing, which has been torn as a symbol of her grief

(A) I

(B) I and II

(C) I and III

(D) II and III

(E) All of the above

20. Which of the stanzas do NOT include images of roundness?

(A) Stanza 1

(B) Stanza 2

(C) Stanza 3

(D) Stanzas 1 and 3

(E) None: All of the stanzas contain images of roundness.

21. The imagery in this poem can most accurately be described as sustained images of

(A) worthlessness suggesting the hopelessness of the lovers’ situation

(B) the globe suggesting the vast distances of the lovers’ separation

(C) roundness suggesting a perfect circle, and therefore the cosmic and permanent union of the lovers

(D) water suggesting the shifting faithlessness of the lovers

(E) water suggesting the bond between the lovers

22. In line 13, to what does the word “which” refer?

(A) Copies

(B) The round ball

(C) The world

(D) The workman

(E) The continents

23. Which of the following is NOT an appropriate association for lines 19–20?

(A) The power of a goddess

(B) The relationship between the moon and the ocean’s tides

(C) The round shape of the moon

(D) The folktale of the man in the moon

(E) The moon as suggestive of unhappy feelings, the opposite of “sunny disposition”

24. What does “diverse shore” (line 9) mean?

(A) Heaven

(B) Hell

(C) Europe

(D) A different place

(E) The ground

25. Which of the following types of imagery is sustained throughout the poem?

(A) Tears

(B) Globes

(C) Coins

(D) Moon

(E) Ocean

26. Line 4 can best be paraphrased as

(A) you are not worth the salt of my tears

(B) my tears are worth something because they reflect your face

(C) my tears are emotionally refreshing

(D) my tears are worth something because they are for your sake

(E) my grief is a valuable feeling

27. What does the speaker ascribe to his beloved in lines 20–25?

(A) The power to break his heart

(B) The power to kill him

(C) The power to influence the natural elements

(D) The power to restrain her grief

(E) The right to seek other lovers

28. In the extended metaphors of this poem, the speaker flatters the beloved through the use of

(A) hyperbole

(B) sarcasm

(C) irony

(D) parallelism

(E) eschatology

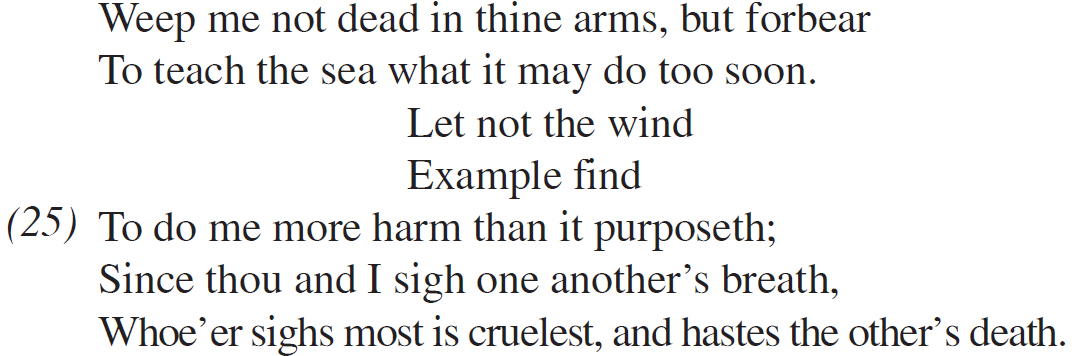

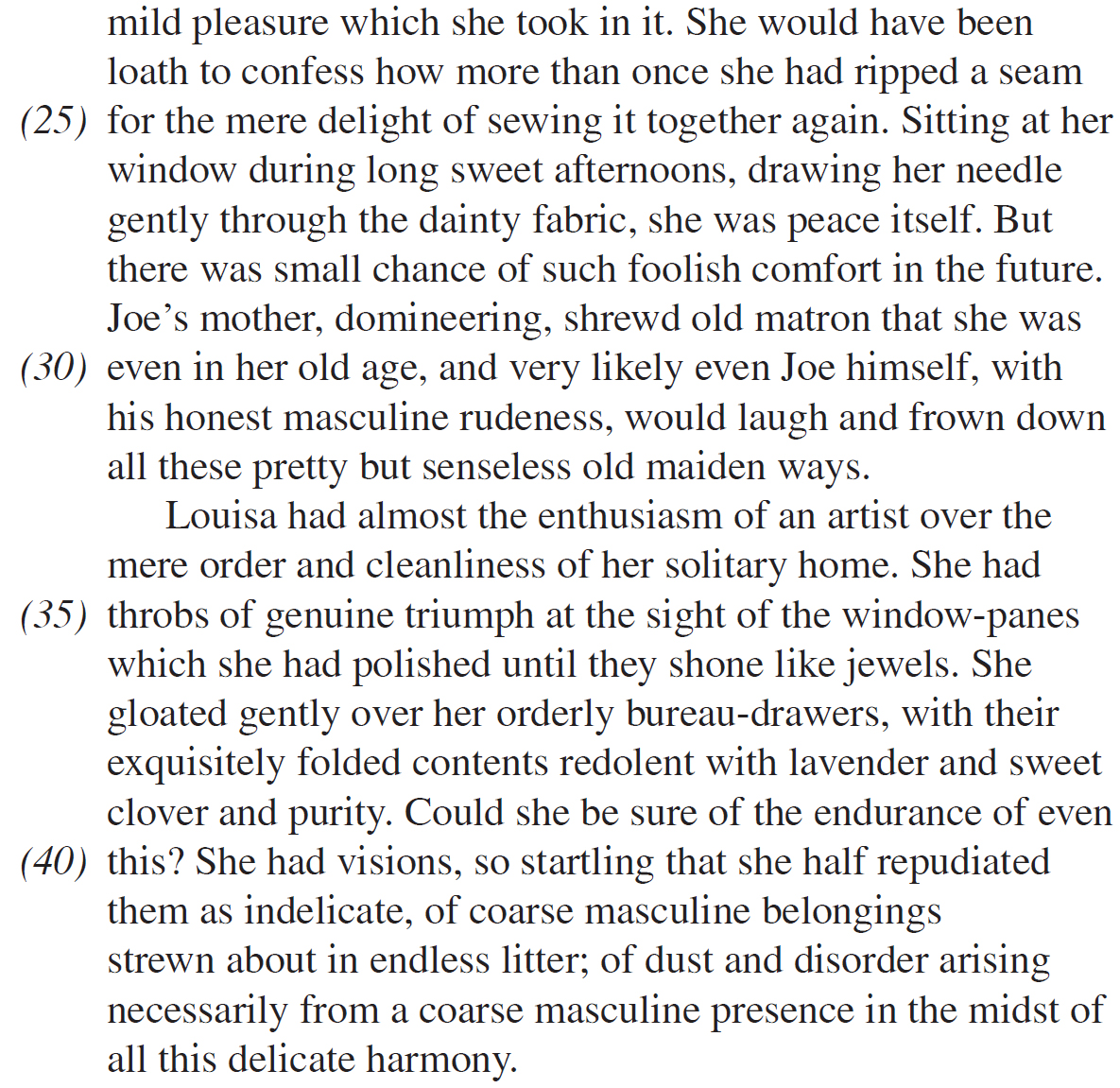

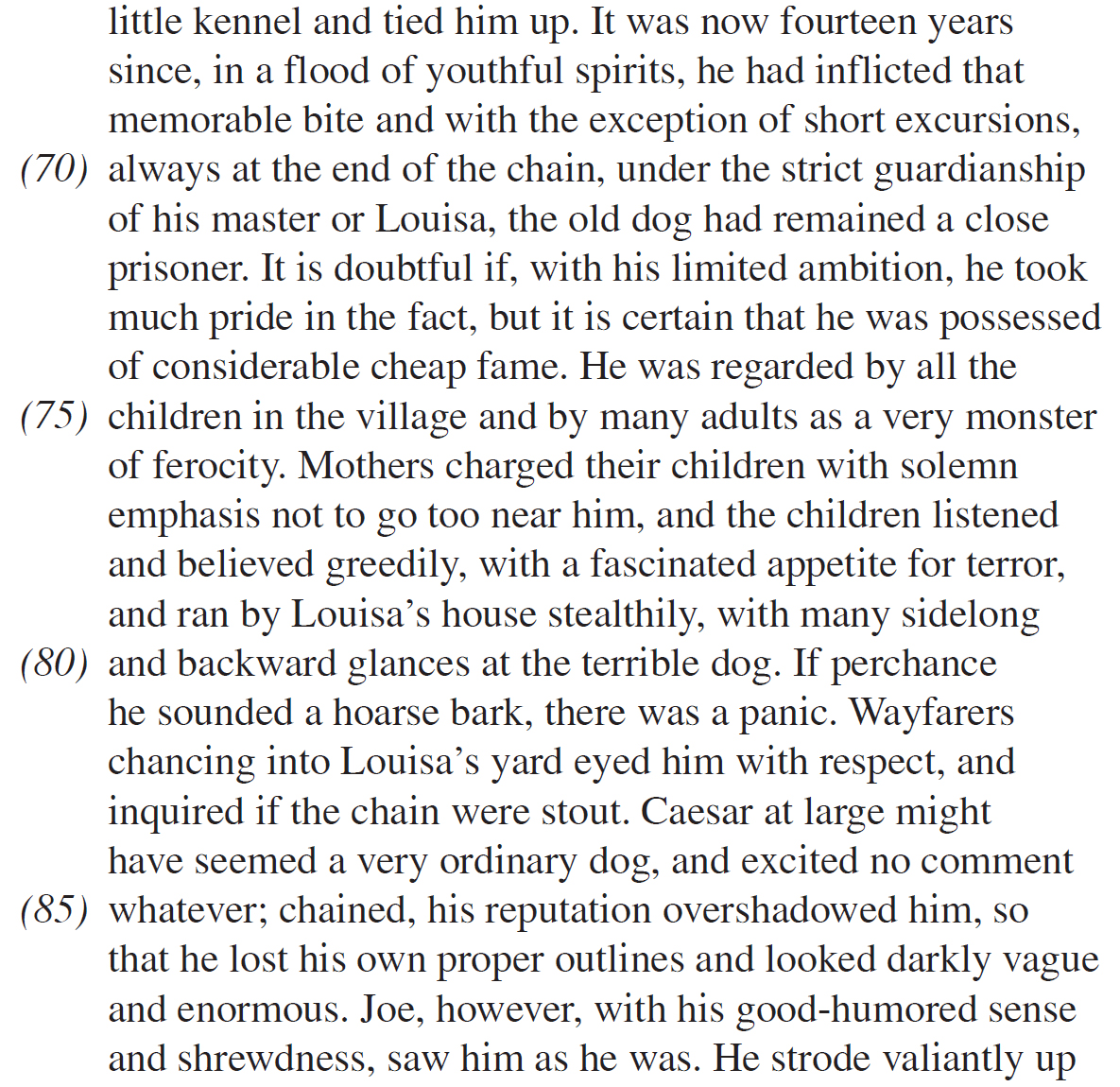

Questions 29–39 . Choose answers to questions 29–39 based on a careful reading of the passage below. The passage, an excerpt from a short story by Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, describes a woman about to be married after a long engagement.

29. In overall terms, how is Louisa characterized?

(A) As a bitter, domineering woman

(B) As a naive, childish woman

(C) As a frightened, foolish woman

(D) As a sheltered, innocent woman

(E) As a selfish, cruel woman

30. Which statement best describes Louisa’s household activities (paragraphs 1 and 2)?

(A) They symbolize the timeless rituals of ancient rural harvest deities.

(B) They demonstrate Louisa’s contented absorption in a traditionally feminine cultural sphere.

(C) They demonstrate Louisa’s mental illness.

(D) They demonstrate Louisa’s repressed artistic genius.

(E) They describe the highest traditional values of Louisa’s town.

31. Which of the following statements are TRUE?

The story of Caesar is used in this passage to reinforce the idea that

I. Louisa has grown too accustomed to her circumscribed life to welcome change

II. cruelty to animals is an indicator of a cruel society

III. marrying is like being conquered by an invading emperor

IV. people can be trapped by unchanging and unexamined ideas

(A) I and IV only

(B) I, II, and III only

(C) IV only

(D) All of the above

(E) None of the above

32. Caesar’s “ascetic” diet (paragraph 4)

(A) reflects Louisa’s poverty

(B) is part of his punishment

(C) reflects a nineteenth-century theory that bodily humors are affected by diet and can change disposition

(D) is part of a religious practice meant to encourage celibacy in hermits

(E) is typical pet food in nineteenth-century homes

33. The word “purity” in line 39 is an example of

(A) irony

(B) metaphor

(C) simile

(D) oxymoron

(E) allusion

34. The tone of the description of Caesar (paragraphs 3 and 4) is

(A) gently satirical

(B) indignant

(C) pensive

(D) foreboding

(E) menacing

35. In context, the word “sanguinary” (line 106) most nearly means

(A) expensive

(B) feminine

(C) masculine

(D) vegetarian

(E) bloody

36. Judging from this passage, which of the following best describes Louisa’s beliefs about gender relations?

(A) Men and women naturally belong together.

(B) Men and women should remain separate.

(C) Men bring chaos and possibly danger to women’s lives.

(D) Women help to civilize men’s natural wildness.

(E) Men are more intelligent than women.

37. In line 41, how is the word “indelicate” used?

(A) To indicate the differences between Louisa and Joe

(B) To indicate that Louisa considered her thoughts inappropriately sexual

(C) To indicate the coarseness of Joe’s personality

(D) To indicate the inferior quality of Joe’s belongings

(E) To foreshadow the vision of Caesar’s rampage

38. Which of the following are accomplished by the Caesar vignette?

(A) It shows us Joe’s down-to-earth, kindhearted character.

(B) It symbolically shows us Louisa’s fears of the future.

(C) It serves as a symbol of what happens to those who refuse change.

(D) It provides a humorous satire of small-town concerns.

(E) All of the above

39. In context, “mild-visaged” (line 54) most nearly means

(A) having a calm temper

(B) having a gentle face

(C) having an old face

(D) being confused

(E) having a kind mask

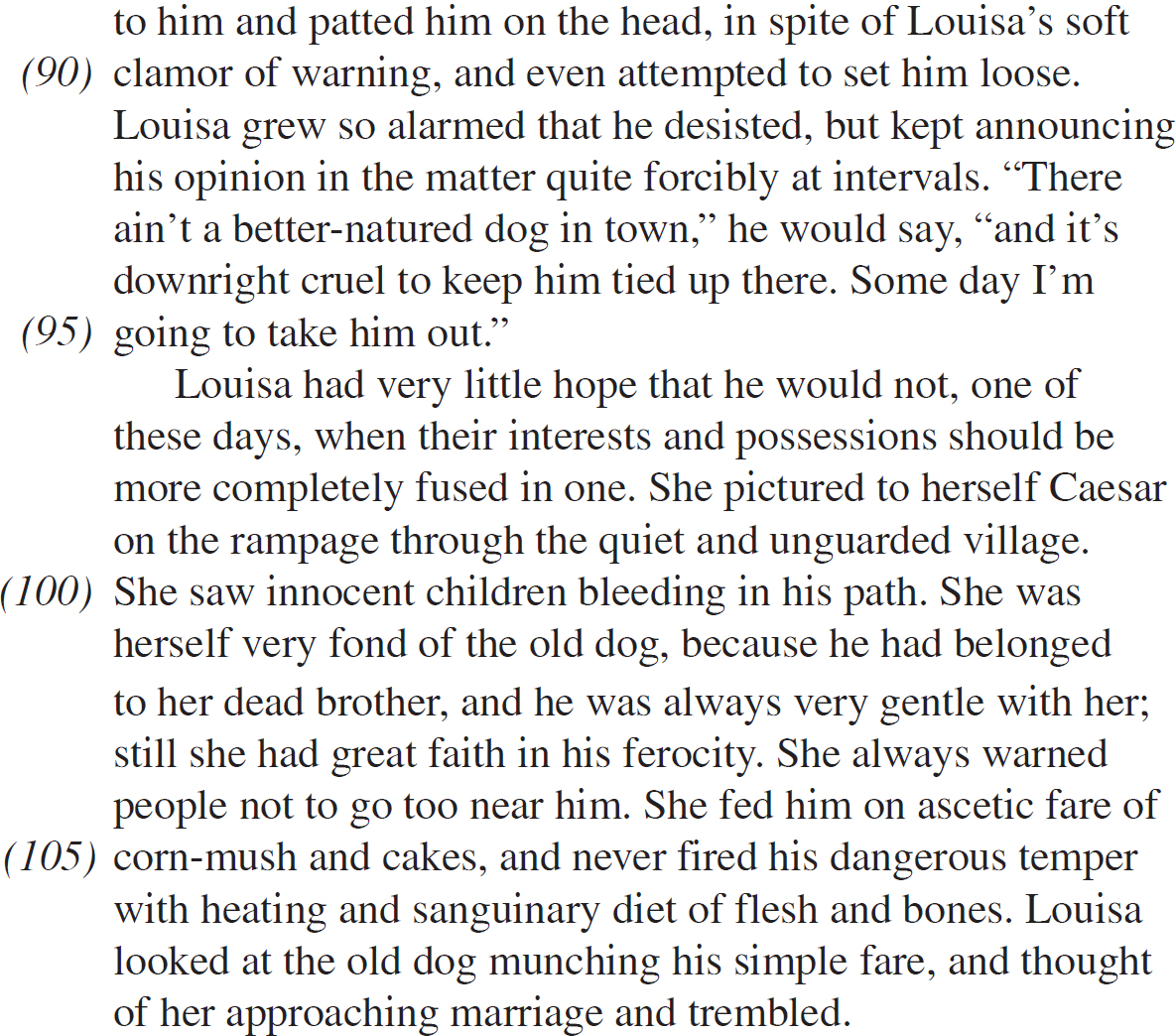

Questions 40–55 . Read the poem below, entitled “Thou art not lovelier than lilacs—no” by Edna St. Vincent Millay, then choose answers to the questions that follow.

40. The poem is best described as

(A) a Shakespearean sonnet

(B) a Petrarchan sonnet

(C) a sestina

(D) a ballad

(E) an ode

41. The speaker’s attitude toward the subject’s beauty is all of the following EXCEPT

(A) critical

(B) tolerant

(C) assertive

(D) perplexed

(E) insouciant

42. In line 10, “delicate poison” is a good example of

(A) paradox

(B) juxtaposition

(C) oxymoron

(D) truism

(E) metaphor

43. The subject of the verb “adds” in line 10 is

(A) him (line 9)

(B) who (line 9)

(C) poison (line 10)

(D) he (line 11)

(E) I (line 14)

44. Which of the following best describes the tone of the poem?

(A) Admonishing

(B) Apologetic

(C) Ironic

(D) Sentimental

(E) Sincere

45. What is the most important thematic point made in lines 1–8 of the poem?

(A) The speaker cannot escape the subject.

(B) The speaker believes nothing is more beautiful than flowers.

(C) The speaker finds nature troublesome.

(D) The speaker relegates the subject’s beauty but recognizes its power over him.

(E) The speaker desires a refuge.

46. The poem is notable for its use of all of the following EXCEPT

(A) alliteration

(B) enjambment

(C) iambic meter

(D) refrain

(E) metaphor

47. The speaker conveys in lines 6–8 that the subject’s beauty is

(A) ethereal

(B) enveloping

(C) insignificant

(D) superficial

(E) exasperating

48. In context, “inured” (line 12) most nearly means

(A) hurt

(B) drunk

(C) conditioned

(D) enamored

(E) drawn

49. In line 8, “it” refers to

(A) “THOU” (line 1)

(B) “honeysuckle” (line 2)

(C) “Thy beauty” (line 4)

(D) “thee” (line 4)

(E) “Find any refuge” (line 7)

50. The function of line 14 is best described by which statement?

(A) The verb “drink” emphasizes the bacchanalian nature of some men.

(B) It contains the subject of the sentence.

(C) The verb “destroyed” emphasizes the secret desire of the speaker.

(D) Its use of punctuation underscores the speaker’s desire to live.

(E) The verb “live” demonstrates the physical superiority of the speaker.

51. In line 9, the poem shifts from

(A) the speaker feeling engulfed by the subject’s beauty to developing immunity from it

(B) the speaker admiring the subject’s beauty to wanting to destroy it

(C) the speaker being enamored with nature to wanting to poison it

(D) the speaker criticizing the subject’s beauty to disdaining it

(E) the speaker giving in to desire to trying to resist it

52. How does the first line of this poem function?

I. It sets up a comparison.

II. The reference to lilacs makes this poem a pastoral poem.

III. It establishes the initial tone.

IV. It states the theme of the poem.

(A) I only

(B) I and III only

(C) II and IV only

(D) I, III, and IV only

(E) All of the above

53. Lines 12–14 of the poem function as

(A) a metaphor

(B) an allusion

(C) personification

(D) a non sequitur

(E) a metonym

54. Which of the following is true of the rhyme scheme in the second stanza?

(A) Rhyme is abandoned in the second stanza.

(B) The final words of lines 9–11 are the basis for the rhyme scheme in the second stanza.

(C) Line 14 completes a couplet.

(D) The rhyme scheme is abba.

(E) Lines 9–12 repeat the rhymes established in lines 5–8.

55. What is the speaker’s meaning in lines 10–11?

(A) The speaker is developing an immunity to poison.

(B) The speaker wants to protect the subject from harm.

(C) The speaker is proving his strength over poison.

(D) The speaker is building a tolerance to the subject’s beauty.

(E) The speaker can drink more than other men.

STOP

END OF SECTION I

IF YOU FINISH BEFORE TIME IS CALLED, YOU MAY CHECK YOUR WORK ON THIS SECTION.

DO NOT GO ON TO SECTION II UNTIL YOU ARE TOLD TO DO SO.

ENGLISH LITERATURE AND COMPOSITION

SECTION II

Time—2 hour

Question 1

(Suggested time—40 minutes. This question counts as one-third of the total essay score.)

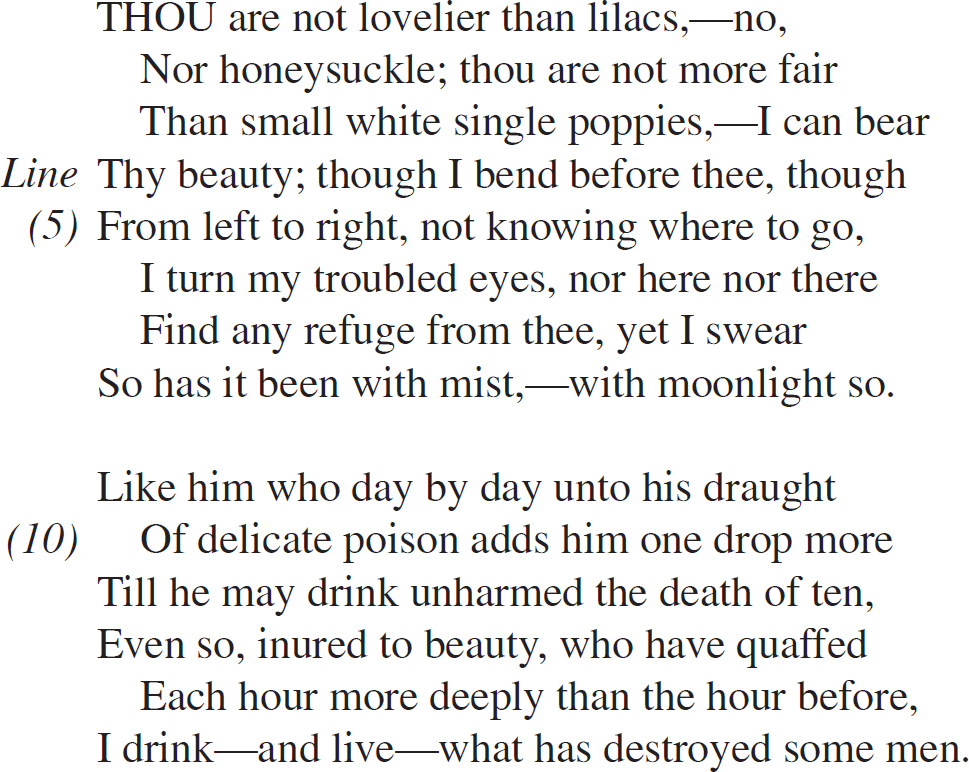

The passage that follows is from “The Yellow Wallpaper,” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1892), which is regarded as an early feminist work in American literature. Read the passage carefully. Then write a well-organized essay in which you characterize the narrator’s attitude toward and interaction with her surroundings. In your essay, analyze the literary techniques the author uses to portray the narrator and her attitude toward her environment. Be sure to include specific references to the passage.

Question 2

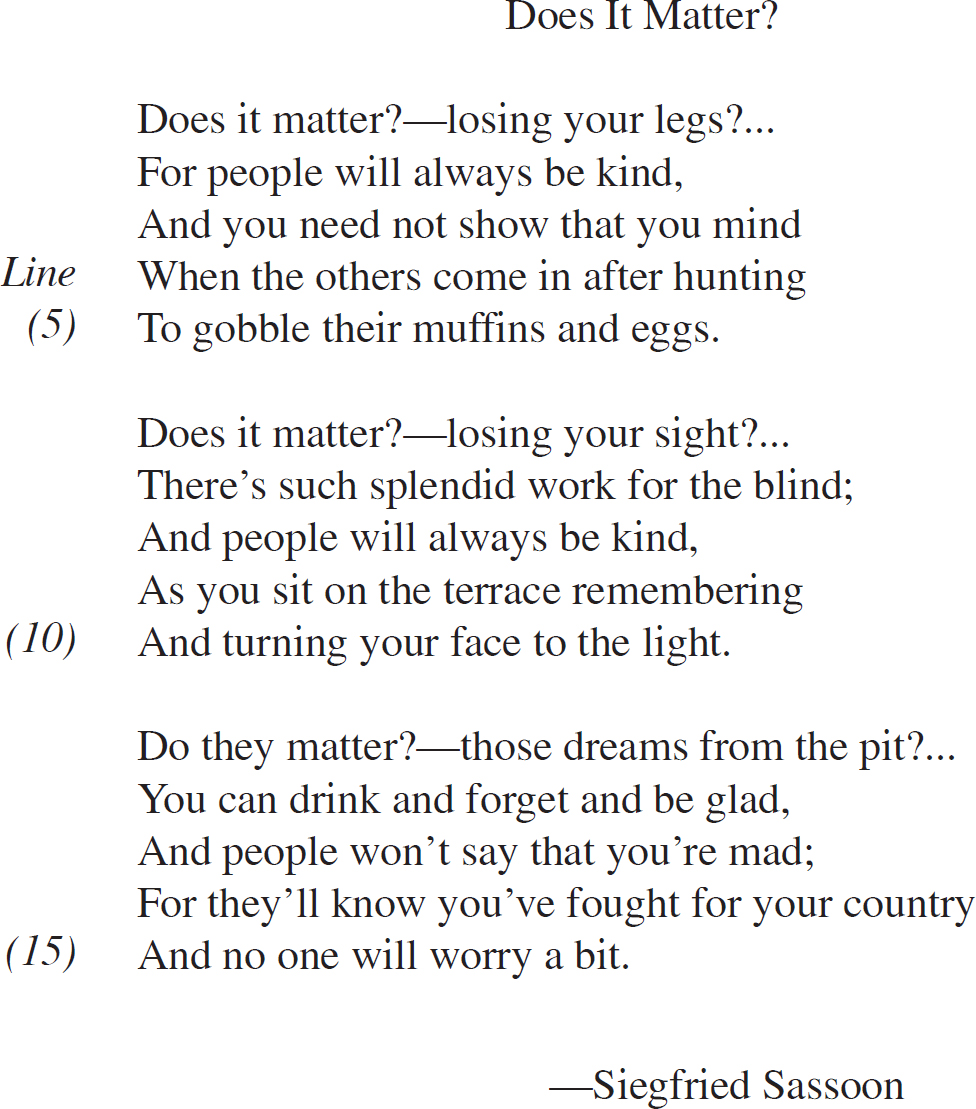

(Suggested time—40 minutes. This question counts as one-third of the total essay score.)

Read the following poem carefully. Considering such literary elements as style, tone, and diction, write a well-organized essay that examines the poem’s view of warfare.

Question 3

(Suggested time—40 minutes. This question counts as one-third of the total essay score.)

In some works of literature, mothers or the concept of motherhood play central roles. Choose a novel or play of literary merit and write a well-organized essay in which you discuss the maternal interaction between two characters and how that relationship relates to a larger theme represented by the work.

You may select a work from the list below, or you may choose to write about another work of comparable literary merit.

A Doll’s House

The Awakening

As I Lay Dying

Beloved

Black Rain

Bleak House

The Color Purple

Daniel Deronda

Dombey and Son

Fifth Business

The Glass Menagerie

Hamlet

The Joy Luck Club

Medea

Mrs. Warren’s Profession

A Room with a View

Pedro Paramo

Pride and Prejudice

The Scarlet Letter

The Seagull

Sons and Lovers

The Sound and the Fury

The Stranger

To the Lighthouse

STOP

END OF EXAM

IF YOU FINISH BEFORE TIME IS CALLED, YOU MAY CHECK YOUR WORK ON THIS SECTION.