_______________________

“The casinos which once welcomed your amateur play, they’re not going to be so happy about your action, now that you’ve become a skillful player.”

Andy Bloch, Beating Blackjack

The adrenaline had long since kicked in. The drive from Foxwoods to Mohegan Sun was a mixture of panic and pride. Our system had proven to be imperfect. D.A. was now persona non grata. On the other hand, we reveled in the ultimate compliment he had been given. It was a rite of passage that let us know they viewed us as a threat.

“Sir, after evaluating your play, it appears that you’re too skilled for us. We would appreciate it if you would play something other than blackjack here,” Shaw had said. His words were polite but his tone was firm, and we’d practiced our response for this situation many times in our heads.

“Uh, okay. Sure, no problem. I wish I were as skilled as you think I am; maybe I wouldn’t lose so much,” D.A. had responded as sincerely as possible. We knew it was inevitable. This time the casino had won the battle but we still intended to win the war. There is an understanding between casinos and card counters. What Shaw was really trying to say was, “We know you’re a card counter and what I’d like to do is take you out back and break your knuckles, but this isn’t the old days so I have to be polite. But the bottom line is … don’t fuck with us anymore.”

It would do us no good to argue the allegation and there was certainly no point in admitting it, either. In some ways, both sides knew their roles and responsibilities. A mutual respect existed as long as those unwritten rules weren’t violated—something that, in time, we would experience firsthand.

The ice had been broken and D.A. had arrived. This wasn’t Semyon or Mike telling us we had talent. It was the opposition and the most genuine form of flattery a pro can have. But it also meant something else. Our system, although it worked for some time, was flawed. It was effective if used in small doses. However, eventually using any single strategy would provide enough of a playing sample size for casino surveillance to figure us out.

The honor that came with D.A.’s first back-off was subdued by the questions that arose. Since I’d called D.A. into that table there hadn’t possibly been enough time for surveillance to monitor his play. Were they watching him bounce around for several hours? Or had they been keeping an eye on him for the last couple of months? What would happen if we went back? Do they know about me? Do they know we’re working together? Did they see the signals? What tipped them off?

The reality was that we’d never know the answers for certain. What we did know was that there were many possibilities and that those possibilities were weaknesses in our game. We needed to figure out a way to better mask those weaknesses.

We decided to use a different strategy at Mohegan Sun. It was something that we’d practiced for hours but hadn’t felt the need to use yet. It had been in our back pocket and the time for its use was now. During our private training with Mike, and through subsequent emails and phone conversations with him, we’d gotten pretty good at table signaling.

This strategy required us to play through several shoes with both good counts and bad. Because we were playing through some negative shoes, the index numbers became all the more critical since they addressed basic strategy variation for both positive and negative true counts. The strategy was that we would both take a seat at nearby tables and when the count started rising rapidly we would signal in the other player to enter our game. Although it was very similar to the call-in strategy we used while back-counting two tables, and the spotter/big player strategy, this was a bit different.

The player who was called in would show very little interest in the cards that came out. He would chat it up with the players around him, the dealer, the pit boss, and the cocktail waitresses. He would often step back from the table to look at his cell phone as if texting or checking messages. He would “accidentally” drop things on the floor and have to pick them up. Depending on the situation, he would go so far as to play up his obnoxious side, generally acting like a gorilla. The terms “gorilla” and “big player” were used by the MIT teams but this was different in that we were combining the two. In our strategy, once the spotter called in the “gorilla big player,” the spotter would then become the signaler. The signaler would indicate to the gorilla BP precisely how much to bet, when to vary from basic strategy, and even when to leave the table.

While the gorilla BP might appear to be the key to this strategy, the real talent came from the signaler, who had to be skilled enough to juggle every aspect of the game. He had to keep the count, calculate the betting and playing for both players, and signal it all to the GBP, who meanwhile would seem to be behaving erratically.

The signaler is not just the quarterback. He’s the offensive and defensive coordinator. He calls all the shots.

The signaler would also kindly (or not so kindly) ask new players who were trying to enter the game to wait until the shoe was complete. The stated rationale would be luck, or bad luck, or any reason he could think of as long as it wasn’t the truth, and the truth was there were too many good cards ready to be dealt and we didn’t want to waste them on other players. Those cards were ours.

If the gorilla BP made a mistake, either betting or playing, it was up to the signaler to relay that message. That signal was a tug of the collar, which meant, “You misread my signal. Here it is again.” The signals themselves were virtually undetectable by pit personnel.

If only the left hand of the signaler was touching the table, it meant to bet one unit. If only the right hand of the signaler was touching the table, it meant to bet two units. Both hands, three units. Left elbow on the table, four. Right elbow, five. Then, if the signaler chipped up from the table minimum, it meant six units.

For instance, if the table’s minimum bet was $25, the signaler would flat bet $25 per hand while using his hands and elbows to signal the proper unit bets for the GBP. But if the required betting unit was six or higher, the signaler would increase his bet to $50 and the corresponding signals would be added to six. Rather than the left hand being equal to one unit, it would be 1+6, or 7. Right elbow would be 5+6, or 11. It felt complicated at first, but we learned it quickly and it worked.

Sometimes the count called for betting a half-unit. For instance, with a running count of, say, 22, with five decks to play, the true count would be 4.4. After subtracting one for the offset, the proper bet would be 3.4 units. In that case the signaler would move his own chip up to the very top half of his betting circle. That would mean that the GBP was to add half a unit to whatever his hand signals indicated.

I handed the car key to the valet and we entered Mohegan Sun. The minute we stepped out of the car and our feet touched casino property our mindsets shifted into attack mode. There was little chance that surveillance had any concerns about us yet, so there was nothing to worry about in entering together. Even still, once we walked through the automatic sliding glass door we immediately separated. We became strangers at that point—strangers who would surely be meeting up at the tables very soon. We avoided the possibility of being seen together as we approached our target blackjack pit.

Still a bit anxious from his earlier back-off at Foxwoods, D.A. stopped for a quick bathroom break and to splash some cold water on his face. That gave me some time to get settled into a game right away. Three tables were shuffling at the same time so I had my pick. Naturally, I chose the least populated game I could find. One person sat at the table.

A few minutes later, I saw D.A. take his seat two tables over, but we were both strategically positioned in such a way that we were facing each other enough to catch a call-in signal from the other.

On the very first shoe, my count rose quickly. It wasn’t quite high enough yet to warrant the call-in, but it was close. It was certainly high enough for me to lean my head in my left hand as my elbow rested comfortably on the soft cushion of the table’s outer edge. That was the new cue to gather his chips and be ready to change tables in an instant if needed. Since we weren’t back-counting tables, the folded arms would look unnatural so we changed the signal.

A few more hands went by and it was finally time. I stood up from my chair to stretch my back for a second, which was our new signal to enter our game. Within moments D.A. sat down at an open seat a few spots away.

Our unit was still $50 and the true count had reached 5. Subtracting 1 for the offset, I interlaced my fingers and rested them together on the felt, indicating to D.A. to bet two hands of three units each. The correct bet was $200, but I reduced the wager since I knew D.A. would be spreading to two hands. There were two bets of $150 for D.A and the table minimum $25 for me.

The dealer busted and everyone won. It was the perfect start to the session. We couldn’t have asked for more. I’d found a table that was shuffling, the count rose quickly, I’d called-in D.A. We made a few hundred dollars in a matter of seconds. Our first test as signaler and gorilla big player was off to a great start. Neither D.A. nor I had spent much time on the art of playing the GBP, but perfecting our acts would come in time. We were just happy that it seemed to be working as planned.

Not only that, but the count rose even higher.

I chipped up to $50, with neither of my hands on the table, indicating a bet of six units.

D.A. accurately placed two bets of $300 on the betting circle in front of him. He was dealt a blackjack on one hand and two jacks on the second. Some of the other players at the table were pleased to see the dealer’s upcard was a 6. Their positive energy meant mild cheers for D.A. catching the blackjack. But in true GBP form, D.A. appeared to be mentally checked out. He spent more time pretending to check his phone than he seemed to be paying attention to his cards, his wagers, or his playing decisions.

That’s because I was doing all that for him.

Out of the corner of his eye he looked in my direction, seeking guidance on the two jacks that stood before him. Stand. That was the basic strategy play. But he also knew that the count was high enough to have warranted two bets of $300 and that meant a possible deviation from basic strategy.

Sure enough, I lightly squeezed my nose which was a clear indication that the correct play was a not to stand. It was to split. Nervously, he pushed forward $300 in chips, which indicated to the dealer that he wanted to split his total of 20. The other players at the table looked on in disgust, but we’d been trained to make the right decisions no matter what possible heat it would bring. We’d learned from the best and we had no intention of questioning what we learned from the former MIT greats. Besides, in this case D.A. was playing the part of a gambler who didn’t much care about the outcome of his bets, but rather in the ongoing texting dialogue in which he seemed to be entrenched.

As was often the case, suckers who consistently made common mistakes, like not surrendering their 16s versus a ten or not hitting A,7 versus a ten, were quick to tell others how to play. Many players also adhered to the ridiculous notion that if one player makes a mistake he “messes up the sequence of the cards for the other players.” In mathematical reality, what one player does has no statistical effect on the outcome of the hands of the other players. Sure, the short-term results could mean that a near-guaranteed win turns into a loss, but it’s just as likely that the “mistake” of one player will help the other players, too. Either way, fighting with players at the table wasn’t a great option, so we frequently asked their permission on plays considered to be questionable.

“I’m feeling really lucky, does anyone here mind if I split?”

In most cases, the act of asking the question would diffuse the potential backlash, but it really didn’t matter either way. We weren’t playing a certain way as a courtesy to others. We were playing to win. Mathematically, splitting jacks versus a dealer 6 was the correct play at a true count of 5 or higher and no answer to the question of whether or not “it was OK” with the other players would have had any impact on the ultimate decision to make the right play. In time, we chose to never split tens, which was a deviation from how we were trained. But we learned that the hard way, through experience. Splitting tens at a true count of 5 or higher was correct and was profitable to our bottom line. The result, however, would prove costly to our longevity, which became more and more important to us over the years.

“I’d like to split, please,” D.A. said as he slid his stack forward.

He’d gained control of his nerves and I was confident that my count was perfect, that my deck estimation was spot on, that my true count calculation was accurate, and that the one and only one correct play was to split. What I didn’t know was that the rules at Mohegan Sun were different than Foxwoods. I’d split tens about a month earlier at Foxwoods when our betting unit was low. I’d also been heads-up with the dealer, who thought I was just a moron.

“I’m sorry, sir. You can’t split tens here.”

“Well, looks like I’ll have to settle for this twenty,” he facetiously quipped.

Then he looked at a little old lady to his left who’d been keeping perfectly quiet and flat bet $50 per hand consistently.

“Will you let me know how it turns out? I need to get a cocktail. I’m getting low.”

D.A. turned away from the table, put his hand in the air and beckoned for the nearest waitress. Meanwhile the dealer turned over a 5 for a total of 11. She then turned over the next card, a king, for the dreaded 21. While D.A. had won on his blackjack, he’d lost on his 20 and I’d lost my $50 bet as well.

We came to frequently experience these types of situations. Just when we started counting our soon-to-be winnings the blackjack gods reminded us that statistical averages are just that—averages. On any given hand, during any given session, over any given month, a great player can lose. It’s a humbling game that requires hundreds of thousands of hands for any real profit to be assured. Situations like this forced us to learn how to deal with the emotional and financial swings of the game. Many card counters fail to have success, not because they don’t possess the skills, but because they don’t have the intestinal fortitude—or the bankroll—to cope with the highs and lows that are inherent in the game. They fail to play through the thousands of hands required to achieve their expected long-term advantage.

Over the first year that I’d been learning and perfecting my game, close friends would frequently ask me if I expected to win each time I sat down at a blackjack table. My explanation was based on one number.

One percent.

While a perfect basic strategy player can get the house edge down to .5%, most players fail to play mistake-free basic strategy, and their disadvantage is more likely to be -1% or worse. As a professional card counter, I can shift that edge to my side, giving me a 1% or better advantage over the house.

Once my friends understood that, I would ask them, “Do you think a casino, with a one-percent edge would want to take action from just one player who made just one single bet of one million?”

Inevitably they would answer “no” and go on to say that with one hand anything could happen.

“Well, then how do casinos make money?” I would further inquire.

“By having millions of gamblers play millions of hands. Over time, that one percent really adds up.”

“Exactly, so all we try to do is play as many hands as possible at as big an advantage as we can. Short-term wins and losses mean nothing to us. So no, I can’t say that I will win the next time I play blackjack, but over time the likelihood of winning is fairly certain.”

What I didn’t get into was what that 1% edge meant in terms of the standard deviation from our expected winnings. In other words, if we were to play for one hour, we’d typically play 75 to 100 hands, depending on how many other players were at the table and how fast the dealer dealt. Assuming we were heads-up with the dealer, it’s reasonable to play 100 hands per hour. If our average bet was $100 and we had a 1% average advantage, our expected win would be $100 (100 hands x $100 x 1%).

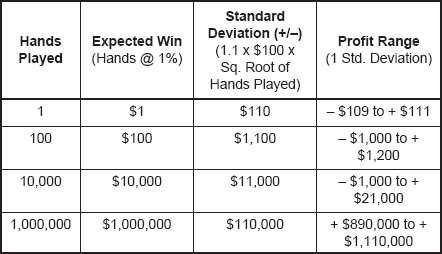

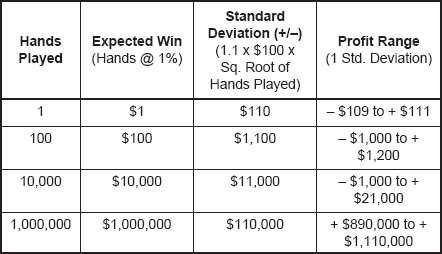

One hand of blackjack played with a 1% advantage and a bet of $100 has an expected value of plus $1. That is, 1% of the wager. Of course, practically speaking, you’ll either win or lose $100, but mathematically, your expected win is $1. However, the standard deviation is about 1.1 times the bet, times the square root of the number of hands played ($100 x 1.1 x 1), or $110. That means you can expect to win $1, plus or minus $110.

Taking it a step further, let’s now assume 100 hands are played. The expected win is $100. The standard deviation can be calculated by taking the square root of the total number of hands played (10) and multiplying it by the one-hand standard deviation ($110) and we can determine that while our expected win is $100, we could easily be plus or minus that amount by $1,100 (10 x $110). In other words, if we played for an hour, we could reasonably expect to be between a loss of $1,000 and a profit of $1,200.

D.A. and I had become students of the game and it was easy to chart our expected wins and standard deviations (assuming an average bet of $100 per hand):

The point is that even after 100 hours of play (10,000 hands) there’s still a possibility that the net result will be a loss. The likelihood that the range will fall within just one standard deviation is 68%. That means 16% of the time the results will be higher than that range. But there’s also a 16% chance it will be lower than that range. So the safest way to evaluate our fluctuations was by using two standard deviations, which would be the range in 95% of our scenarios. Therefore, 10,000 hands at a $100 average bet would yield between negative $12,000 and positive $32,000 (expected win of $10,000, plus or minus $11,000 x 2). That’s quite a range.

Of course, all of this assumes a consistent bet of $100. We employed a significant betting ramp depending on the count. As the count increased, so did our betting. With an increased range of bets and an increased average bet, the standard deviation would push even higher.

That’s why losses like the one we just experienced (when a dealer makes a 21 out of a likely-to-bust hand), well, they were a part of the game. What mattered was playing right, getting our money out on the table when we had the best of it, and playing as many hands as we possibly could. Eventually we’d play enough hands for it to become a statistical fact that our expected win would be positive and our range of returns would also be positive. Fluke losses would happen from time to time, but they were nothing more than small mosquito bites along the way, something we learned not to waste our energy on. It was at that exact moment that we began to understand the value of emotional immunity. Wins, losses, big bets, small bets, back-offs, call-ins, signaling—they were all a part of the job of being a professional blackjack player and I loved every minute of it.

We walked away from that session with a loss, but we’d attained new enlightenment. Bad beats were something we would learn to live with, but with that session our objective became clearer: Play hands, play more hands, and play even more hands. As many as we could.

In Blackbelt in Blackjack, Arnold Snyder charts an estimated number of hands per hour depending on the number of players at the table, based on 8-deck shoes:

1 players = 200 hands per hour

2 players = 160 hands per hour

3 players = 140 hands per hour

4 players = 120 hands per hour

5 players = 100 hands per hour

6 players = 80 hands per hour

7 players = 65 hands per hour

Our goal was to average a minimum of 100 hands per hour and we generally played 6-deck shoes instead of 8. So we were usually dealt slightly fewer hands per hour due to the increased shuffling time. For that reason I’d come to appreciate the quick hands of a fast dealer. My brain could easily keep track of the count no matter who was dealing or how fast they were. I’d spent countless hours glued to my blackjack-simulation software with the dealer-speed setting pushed to the max. The counting had become easy. Fast dealers meant more hands. Slow dealers bored me.

We had three tactics to work with: wonging (back-counting), call-ins, and signaling. We could choose ahead of time which tactic we wanted to employ and then come back another time and use a different one. We knew that each tactic worked on its own, but as we discovered from D.A.’s back-off, no one given tactic was appropriate all the time. The term “burned out” is often viewed by blackjack outsiders as meaning emotionally exhausted, but in the blackjack community it meant being asked to leave casinos and never come back. Our tactics needed to be used in small doses or we’d risk getting burned out.

We were young in our blackjack careers and playing thousands of hands with an edge over the house was a part of the process. The goal was also longevity. If we used the three tactics in moderation, we would accomplish that. By not limiting ourselves to one technique we could surely fly under the radar and build long and financially rewarding playing careers. These three tactics were the answer.

Or so we thought.