V. THE VIEW FROM BELOW: MUNCIE, INDIANA

V. THE VIEW FROM BELOW: MUNCIE, INDIANA

Muncie, Indiana, in 1924 was an industrial city of about 36,000 people in the Midwestern corn belt. No one claimed it was lovely—its local newspaper, indeed, admitted that it was “unfortunate in not having many natural beauty spots.” Its primary employers were mostly subsidiaries of the big automobile companies or suppliers to them, making glass, wire, and automobile parts. Its residents were more than 90 percent white, with scatterings of black and foreign-born populations. About half of its adult residents had been born on farms, and 70 percent of those in employment were working class—predominately factory workers, with an admixture of clerks in offices and retail stores and semiskilled services, like waiters, barbers, and beauticians.

We know quite a lot about 1920s Muncie because a team of cultural anthropologists, led by Robert S. and Helen M. Lynd spent eighteen months there in 1924 and 1925. They called the city “Middletown” to ensure a measure of anonymity for their subjects. As anthropologists, they applied the methods they would have used if they were studying exotica like the Trobriand Islanders. They lived in the community, participated in many of its activities, conducted hundreds of interviews, and collected many more anonymous questionnaires. Their interviews ran the gamut from top officials down to a large sampling of high school students. The objective was to document how a middle American community made its living, the nature of people’s home lives, how they worshipped, what they did for entertainment, the sources of their anxieties, the kinds of social pressures they were under, and their hopes and dreams for the future. The team returned in 1933, primarily to document how the townspeople had dealt with the Depression. 28

Muncie had once been a strong union town. Around the turn of the century, half of all production workers were in unionized skilled or semiskilled trades, and had completed apprenticeship programs. It was the unions that had insisted on workplace safety rules that sharply lowered accident rates, and the unions had also pushed through a state worker’s compensation program. Much of the town’s social life had been organized around the unions. Unions led the holiday parades, and the results of interunion baseball games—“the Sandmolders vs. the Machinists”—were grist for the sports pages. But the unions lost their base when Ford deskilled manufacturing. In a Ford plant, the machine embodied the required skills, while the human operator was its servant—turning it on, loading the work piece, keeping it lubricated, changing a cutting tool, all the time working to the machine’s tempo. Some factory owners deliberately forced strikes so they could install new generations of machinery during the shutdowns.

By 1924, the median Muncie worker was a male factory machine operator. He had not finished high school, did not belong to a union, and had no formal apprenticeship training. He was paid by the hour for the time he actually worked. There were almost no benefits, although a handful of the bigger companies were experimenting with group life insurance. Despite the improvement in industrial accidents, the numbers were still atrocious. About 20 percent of the factory workforce lost time each year because of an industrial accident; 43 percent of them lost more than eight days of work, 5 percent lost an eye or some bodily appendage, and about half of 1 percent died. Few people had health insurance, but the day’s medical capabilities were rudimentary and appropriately inexpensive. Several of the larger plants had a nurse or other medical professional either on site or on call in case of an accident.

In Muncie’s new Ford-style plants, most jobs required only a few days of training. But even the work of the remaining skilled men had been substantially routinized. Gear-grinding was a skilled task in most plants, and when factories were smaller, a man qualified to grind gears was expected to work on a variety of other similarly demanding tasks. Not so in the new era of mass production. A Muncie plant manager pointed out a gear-grinder to one of the Lynd researchers and said, “There’s a man who’s ground diameters on gears here for fifteen years and done nothing else. It’s a fairly highly skilled job… [but] it’s so endlessly monotonous! That man is dead, just dead!”29 The manager of a large metal-working plant told the researchers that 75 percent of their hires could be trained in a week or less, while in glassblowing, one of Muncie’s premier industries, and formerly one of its most skilled, 84 percent of the workers needed a month or less training. Only about 6 percent of the tool-using jobs in 1925 Muncie’s glass industries required journeyman glassblowers.

Blue-collar work was hard, and the hours were long. Most plants started work at 7 a.m.; the standard workweek was five ten-hour days, and a half day on Saturday. (Executives usually started their workday at 8:30 a.m.) And the pay was poor. The US Bureau of Labor calculated that a minimum standard of living for a Muncie family of five required annual earnings of $1,903, or about $36 a week. The Lynds’ sample of Muncie working-class families with five or more members showed that only a quarter of them made that much, even counting the income of working wives and children. Jobs were also uncertain. The year 1923 was a good one for Muncie, so three-quarters of the male family heads had worked a full year without layoffs. The next year, the economy turned sour, and 43 percent of the sample lost a month or more of employment. One large plant that had ended 1923 with 802 men had cut back to 316 by midsummer 1924, with a third of them working on short hours. Except for the genuinely skilled men, and perhaps some favored long-term employees, employers generally did not commit to hire back their men when a layoff ended. Factory hands were factory hands: the laid-off men understood the game and lined up at other factory hiring offices as soon as they were let go.

Factory workers all faced the likelihood of dying in poverty, since the plants almost uniformly terminated men when they could no longer keep up. Plant managers told the Lynds: “The principal change… has been the speeding up of machines.… [We have] no definite policy of firing men when they reach a certain age… but in general we find that when a man reaches fifty he is slipping.” “In production work forty to forty-five is the age limit because of the speed needed in the work. Men over forty are hired as sweepers and for similar jobs.” “Fifty per cent of the men now employed by us are forty and over, but the company has decided to adopt a policy of firing every employee as he reaches sixty.” “The age dead line is creeping down on those men—I’d say that by forty-five, they’re through.”30

Workers and their wives understood the bleakness ahead. “Whenever you get old they are done with you. The only thing a man can do is to stay as young as he can and save as much as he can.” “The company is pretty apt [not to lay him off]. But when he gets older, I don’t know.” “I worry about what we’ll do when he gets older and isn’t wanted at the factories and I am unable to go to work. We can’t expect our children to support us and we can’t seem to save any money for that time.” “He is forty and in about ten years will be on the shelf.… What will we do? Well, that is just what I don’t know. We are not saving a penny, but we are saving our boys [who were both in the local college].”31 Many of these families had been raised on farms, at a time when the farm itself provided a modicum of security. If a farm couple managed their farm adequately and stayed healthy, they could pass the farm to their children and stay on in their dotage, contributing work as they were able. But in the 1920s, agriculture was industrializing as well, and forcing small farmers off the land. As the security of farming became ever more illusory, the chance to earn regular weekly cash packets in a booming urban industrial economy was tempting, safety net or no.

On top of the cruel financial pressures, working-class people were besieged with new ways to spend money. By 1924, Insull’s company and other electrical conglomerates were steadily wiring up the towns and cities in the upper Midwest, and almost everyone in Muncie had electricity, with its spreading vistas of new things to buy. Electric irons and curling irons! Washing machines! Refrigerators! Toasters and waffle irons! Radios! For working-class women, who did not send the laundry out as their betters did, the washing machine was a miracle, much as the iron stove was for nineteenth-century farm women. No more boiling soiled clothes and scrubbing them on a washboard with raw-red hands. Working-class Muncie families frequently bought a washing machine before they had an indoor toilet.

It wasn’t just about durables. The barrage of mass media—tabloids, radio shows, movies—turned advertising into an important industry. Muncie interviews confirm that children exerted considerable independent spending pressure. Fashion trends from New York were replicated in mass-produced knockoffs that sold throughout the country. Cosmetics became a major expense. In previous eras, women had used mostly powder and perfume, since “painting” one’s face bordered on immorality. The heavy makeup used in Hollywood changed all that. Max Factor, who became famous as a movie cosmetologist, Helena Rubenstein, and Elizabeth Arden rolled out a flood of new products throughout the 1920s and 1930s—eyebrow pencils, mascara, lip gloss, liquid nail polish, rouges, and compacts to allow constant attention to the state of one’s face. In Muncie, the push to conform escalated in high school for both boys and girls, although the pressures were greater on girls. One business-class mother said, “The dresses girls wear to school now used to be considered party dresses.” Her daughter, she said, would feel “terribly abused” if she had to wear the same dress two days in a row. A fifteen-year-old boy admonished his mother that if his sister didn’t have silk stockings when she started high school, “none of the boys will like her or have anything to do with her.” There were many instances of the daughters of working-class mothers who could not afford the clothing standard simply dropping out of school.32

Measured by its economic impact, the evolution of consumer credit was nearly as portentous as the light bulb or the internal combustion engine. Credit was suddenly readily available for homes, for consumer durables like cars and washing machines, and even for routine purchases like clothing. At the turn of the century, people in Muncie rented their houses, but by the 1920s, they had clearly shifted to buying homes with borrowed money. There were four building and loan societies in Muncie in 1924. One of them, not the largest, had 7,090 members and $2.7 million in assets. Loan rates for members were $0.25 a week ($13 a year) for each $100 borrowed. Those were excellent terms: standard building society practice was to lend up to two-thirds of a property’s value, with full amortization over an eleven to twelve year period, which implies an annual interest rate of 6–8 percent. People without building society accounts could get financing from other lenders, but the terms were harsher—the maximum loan was usually 50 percent of the purchase price, and amortization periods were five years or less. Even worse, if they missed a payment, they were subject to losing the home and all their accrued equity.

Point-of-sale credit radically changed working-class attitudes toward consumption. By 1925, consumer installment credit had soared to $11.5 billion, up from almost nothing in 1920. Big-ticket items like cars and furniture led the parade, but there were “easy” payment plans for pianos, radios, phonographs, vacuum cleaners, and even impulse items like jewelry and clothing, which by themselves accounted for half the total borrowing. Average maturity of the loans ranged between twelve and eighteen months for major durables, down to only five or six months for clothing and jewelry and smaller durables like radios.33

But the cultural artifact with the greatest impact on savings and social behavior was undoubtedly the affordable automobile. A new Model T, with a base price of $350, could be readily financed for $35 a month for a year, or about an average male’s week’s pay, and be owned free and clear—unless there was a layoff or a sickness. Some families, even in 1924, were financing new cars with mortgages on their homes. One advertisement had a gray-haired banker saying: “Before you can save money, you must make money.… I have often advised customers of mine to buy cars, as I felt that the increased stimulation and opportunity of observation would enable them to earn amounts equal to the cost of their cars.” (Later during the Depression, advertisements pushed the value of a car in widening the job search.) One woman with nine children told the Muncie researchers, “We’d rather go without clothes than give up the car. We used to go to his sister’s to visit, but by the time we’d get the children shoed and dressed, there wasn’t any money for carfare. Now no matter how they look, we just poke ‘em in the car and take ‘em along.” There was also evidence of people cutting down on food to keep the car.

At first, owning a car was a family-cohesive force. “Sunday drives” became a standard recreation. Working-class people, in particular, relished the opportunities to drive into the country for a picnic or just for sightseeing. But as cars became a standard piece of family equipment—by 1929, the ratio of cars to families in Muncie was about 1:1—they became a source of tension between parents and older children. One mother lamented that in the pre-automobile days, families would sit outside their houses on summer evenings chatting, maybe even playing music or singing. Now, a father reported, his daughter complained, “What on earth do you want me to do? Just sit around home all evening?”34

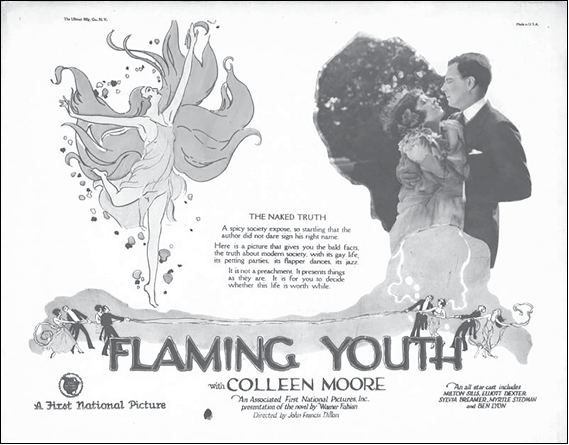

The combination of cars and pre-Code movies was especially potent. In 1925, Muncie had nine movie theaters, open daily from 1 p.m. to 11 p.m., showing twenty-two different films a week for a total of three hundred showings. Comedies, especially those of Harold Lloyd, were the most popular movies. Right behind, though, were so-called “sex” movies. In one week, The Daring Years, Sinners in Silk, Woman Who Give, and The Price She Paid were all running at the same time. The advertisement for Flaming Youth proclaimed, “neckers, petters, white kisses, red kisses, pleasure-mad daughters, sensation craving mothers… the truth, bold, naked, sensational.”

The movies were a peephole that allowed working-class, god-fearing Americans a glimpse into the lives of the upper classes. The poster for Flaming Youth promised the “Naked Truth” about a “spicy society” and its “gay life, its petting parties, its flapper dance, its jazz.”

The famously straitlaced morality of American working classes had depended in some measure in not knowing how the elites really behaved.* Now the movies offered master classes in such deportment, even as the automobile supplied readily available privacy. One juvenile court judge noted that of thirty girls brought before him for “sex crimes”—how he defined them isn’t clear—nineteen of them had occurred in cars, which had become “mobile houses of prostitution.” The transition may have been particularly hard on working-class girls, who typically had much less access to sexual education than their better off peers. All of the “business-class” wives interviewed approved of and practiced contraception. But in the working class, fewer than half of the wives interviewed used any contraception at all, and 40 percent of those used primitive methods, like withdrawal. And of those using “scientific” methods, only half used the more up-to-date methods standard among the business-class wives. All the business-class wives had engaged in sex education with their daughters, while a large fraction of the working-class wives had not—or if they had, they might well have conveyed misinformation. The good news was that most mothers realized that sex education was important, although many working-class mothers felt incompetent to give it. There was no sex education in Muncie schools, churches, or social organizations like the YM/YWCAs.35