V. WHAT HAPPENED TO FORD?

V. WHAT HAPPENED TO FORD?

In his memoir, Sloan analyzed the mid-twenties transformation of the automobile industry. Ford’s initial success with the Model T proved that there was a huge market for inexpensive, reliable basic transportation. By the 1920s, however, the industry was maturing. Millions of cars were on the road, and as the first wave of car buyers traded up to more advanced automobiles, a growing used car market competed for the wallet of the basic transportation buyer. The price discount on a used Buick, with its powerful engine and elegant styling, made it a formidable competitor to a new Model T. Sloan writes that Ford somehow missed this, adding “Don’t ask me why.” And he skewers the legend that the Model T was a “great car expressive of the pure concept of basic, cheap transportation.” It died, he says, because it was no longer “the best buy, even as raw, basic transportation” and was “noncompetitive as an engineering design.”35

Ford’s people, including Edsel Ford, his son and president of the company, had been telling him the same thing for years. They worried particularly about the Chevrolet, which was now openly targeted at the Model T market. Henry refused to consider any new model car, although he had long been working quietly on a “radical” new design without making much headway. Edsel did force a number of cosmetic improvements on the Model T in 1925—an option for a closed body (it was a kludge, because the basic Model T was too light to carry it), a slightly longer and lower chassis, a little more leg room, better cushions, some color choices for some models. But when the new Chevy came out, it sported a visible oil gauge, a speedometer, a modern sliding three-speed gear shift, a much better lubricating system, more reliable spark plugs, a foot accelerator (the Model T still used a hand accelerator), much better springs, and a water-pump cooling system (the Model T’s siphon-based system boiled over at the slightest engine strain). As roads improved, people wanted faster cars, and the Chevy was a lot faster than the Model T. Henry Ford was still proud that the Model T was the workhorse of rural America. Sloan was content to allow him that honor.36

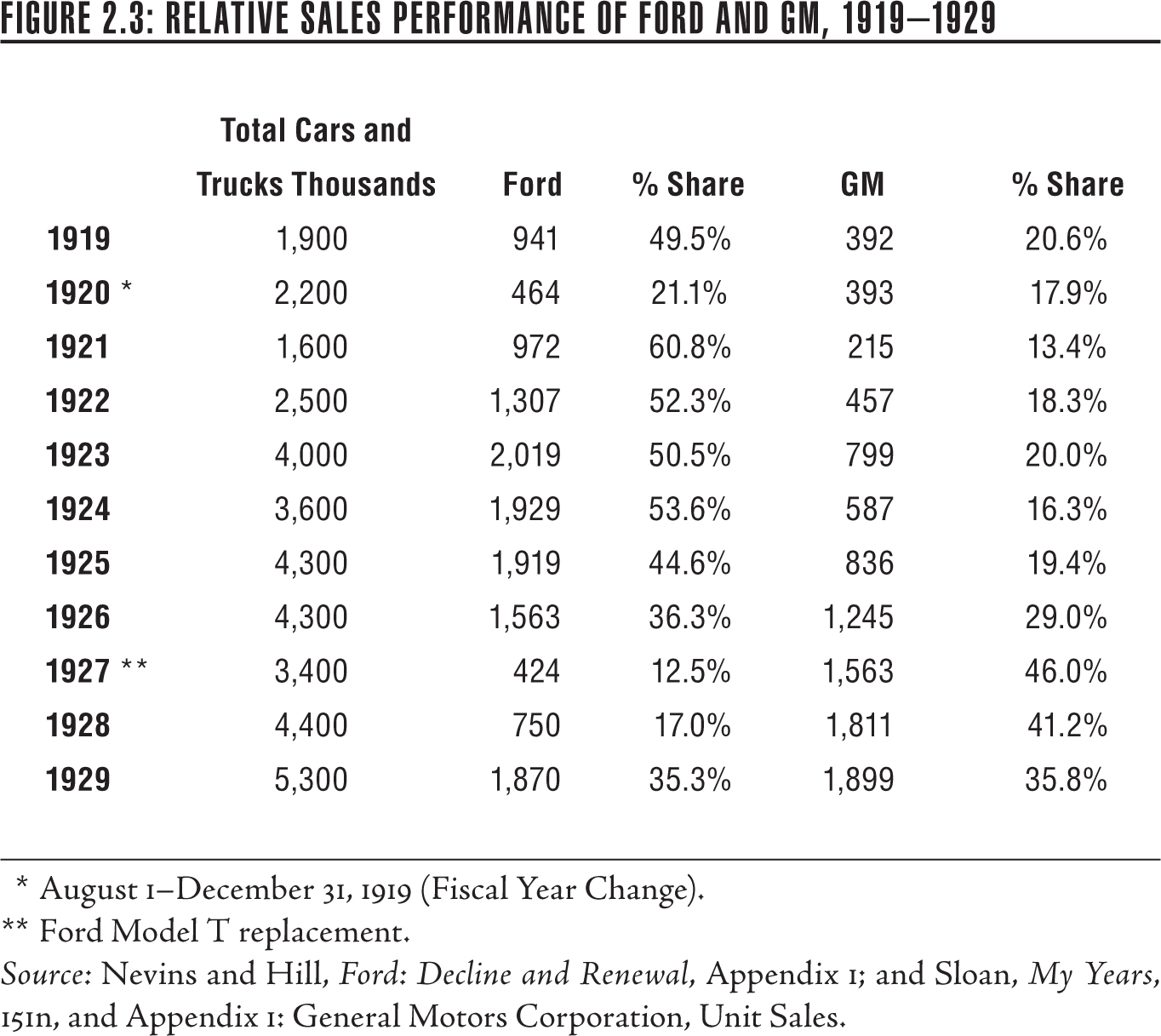

The year 1923 was the industry’s first four million-unit sales year, and total sales of new cars and trucks plateaued at about that level for most of the rest of the decade. Ford’s share of the postwar market peaked at 61 percent; by 1926, it slipped to only 36 percent, and its unit sales were 200,000 lower than its 1923 peak. Chevrolet hit 800,000 units by itself in 1926, while the rest of GM sold 450,000 units, for total unit sales of just under 70 percent of Ford’s. Henry finally saw the light. While still insisting that the Model T would not be changed, in August 1926 he quietly convened his best engineers for a complete overhaul of the Ford product.37

The next two years may have been Henry’s finest hour. Much as he had done during the design of the Model T, he spent almost all of his time directing the redesign. He made a few mistakes, like insisting on an in-house electric starter instead of the Bendix starter, which had become the industry standard. (After a burst of customer complaints, he adopted the Bendix.) But overall the Model A, as it was called, was a splendid car. The engine was powerful but unusually light—the product of a joint design between Ford’s automobile engineers and designers from his aircraft division. The car was also very quick, with excellent acceleration, and a top speed of sixty-five miles per hour. There was unprecedented use of welding, rather than nuts and bolts, and generous use of high-quality steel forgings for durability and stability. The Model A was handsome enough, longer and lower than the Model T; some thought it looked like a “little Lincoln,” which was a compliment. It had both a safety glass windshield and four hydraulic springs, so the ride was safer and smoother than the Chevy’s. Standard features also included hydraulic brakes, a best-in-class slide gear shift and an excellent new transmission. Topping it off, there was a variety of colors, with high-fashion names like balsam green, rose beige, and andalusite blue.

Astonishingly, Ford made the switch cold turkey. In January 1927, he acknowledged that the company would produce fewer cars that year, with no “extraordinary changes in models.” But the phrase that caught the press’s attention was the throwaway, “although, of course, the whole industry is in a state of development and improvement.” By spring, rumors were flying about a new Ford car. Finally, in May, Henry announced that the company would soon produce its fifteen millionth Model T, and then shut down the production line for good. The event was marked with a minimalist ceremony. Henry and Edsel drove the last Model T from the assembly line to the Dearborn Engineering Laboratory fourteen miles away. In the yard were Henry’s first car, from 1896, and the first Model T. He drove each of them a lap around the plaza. That was it. Informed speculation was that the new car would be unveiled in July, or at least by early fall. But Ford made no announcements, for final designs weren’t yet finished, and the engineers were still figuring out how to make it.

The death of the Model T brought a torrent of nostalgia. Dealer inventory rapidly cleared. Many Model Ts were sold at a premium over the list price, which helped to tide the Ford dealerships over the chasm between the Model T and the Model A. It was rough on the workers; the factories did not totally shut down—Ford still sold trucks, tractors, and airplanes—but the great majority of the rank and file were on layoff.

For the company’s thousands of tool and die makers, the transition was a bonanza of overtime. A drawback of a Ford-style automated production line is that it assumes a stable product. But the Model A had 5,580 parts, all of them new, and many of them radically different from those of the Model T. Even for similar parts, the drive toward better stability and integrity required new manufacturing processes, like electric welding. Both the Model A and Model T production lines had about 45,000 machine tools, but only a quarter of them could be used in both lines. Another quarter were completely new, and often had to be designed from scratch, while the remainder required extensive rebuilding and refitting to be used on the new lines—adapting the machines for making two gears on an axle assembly, for example, cost $500,000. The production sequences for the two models were also quite different, so production and assembly lines had to revised and retimed, and the workforce retrained.38

Sightings of prototypes were breathlessly reported in the daily press. In November, two Chicago dealers, desperate for a glimpse, drove to Detroit. Fortuitously, they ran across Henry and Edsel test-driving one of the new Model As, and received an enthusiastic demonstration that got headlines in the trade press. The first press showing was on November 30, and it was a smash: “Through blinding eddies of snow and over rutty roads rim-deep in mud, the car was driven at sixty-two miles an hour, whirled about, brought to abrupt starts, and taken around curves at a breathtaking pace.”39 Models trickled into major dealerships and for exhibits in December auto shows.

Much like the Lindbergh flight, the Dempsey-Tunney battles, and Babe Ruth’s home-run splurge, the actual release of the Model A became another 1920s media extravaganza. In the United States, ten million people were estimated to have seen it within the first thirty-six hours. In New York City, 50,000 people put down cash deposits. Special trains carried crowds to an exhibit in London; police had to control mobs in Berlin; 150,000 people showed up for a demonstration in Spain. Within two weeks, the company had 400,000 orders.40

Excruciatingly for Ford, year-end production was stuck at just a few hundred a day. Although the demonstration cars got raves, there were problems getting them out of the factory. A number of components needed to be redesigned and retooled. The production and assembly lines still weren’t tuned. Almost all the Ford machine tools were highly specialized, single-purpose instruments ordered in small lots, and some were still not available. Hand workers could be substituted, but they slowed production. As deliveries to the agencies stayed at a trickle, the dealer network was in open-throated revolt. May 1928 marked a full year from the announcement that the Model T would be scrapped, and Model As still couldn’t be had. A profitable black market was already developing; the lucky customer who had a Model A could resell it at a premium, and some dealers were rumored to be auctioning their inventories to the highest bidder. But by about midsummer the most annoying operating kinks were worked out, and production finally got untracked, soaring to more than 4,000 new cars a day—Model T-style volumes at last.

Allan Nevins called the Model T-to-Model A transition “one of the most striking achievements of twentieth century industrial history.”41 That’s true enough, and a tribute to Henry Ford’s vision and organizing capacities and the great skills of his team. From a broader perspective, however, the real story is one of colossal management failure, stark testimony to Henry’s pigheadedness, his cultivated ignorance of market trends, and his cavalier dismissal of the rising panic among his senior team. Recovering from the disaster was a stunt-pilot’s feat—almost willfully creating a crisis for the thrill of exercising his peculiar genius. Sloan was just then demonstrating how to manage a company bigger and more complex than Ford’s with careful planning, focused market and technical research, regular and predictable product improvement, and a minimum of heroic rescue operations. Over the long term, the self-inflicted wound of the Model T not only cost Ford its industry leadership but opened the door to a powerful new third competitor in the person of Walter Chrysler.

Figure 2.3 shows the relative sales performance of Ford and GM. Note the 900,000 unit dip in national car and truck production in 1927 when Ford was in shutdown mode. Assuming a $500 price per unit, that would amount to about a half of a percent of lost GDP, although Ford’s huge investment in new plants may have offset a fifth of that. Given the booming economy, few people beyond Ford shareholders and workers would have noticed.