VI. THE TWILIGHT OF THE GODS I: INSULL

VI. THE TWILIGHT OF THE GODS I: INSULL

Samuel Insull was never that interested in amassing a personal fortune. By the mid-1920s, the congeries of companies and properties that made up the Insull utility combine disposed of some $3 billion in assets, engaged in annual financing activities that routinely exceeded $500 million, and delivered to people in thirty-two states more electric power than was consumed in any other country in the world. Insull, indeed, had a claim to have invented his industry, much as John D. Rockefeller and Henry Ford invented theirs. An informal estimate of Insull’s fortune in 1926, however, showed that he was not especially rich, with a net worth of about $5 million, including his home. Most of his $500,000 annual salary went to civic and charitable organizations, especially around Chicago.48

Insull’s companies, at this stage, comprised four dominant entities—Commonwealth Edison, serving greater Chicago, possibly the most efficient electrical utility in the world; Peoples Gas, Light, and Coke Company, serving gas to the greater Chicago area; Public Service of Northern Illinois, a large regional; and Middle West Utilities (MWU), a giant holding company for hundreds of utilities extending from the East Coast to the Great Plains. MWU was built out with layers of subordinate, but very large, companies, like North American Power, Mississippi Valley Utilities, New England Power, and Central and Southwestern Utilities.

Insull kept control of his sprawling empire through the simple device of peopling the major subsidiaries’ boards of directors with the same dozen or so men, usually with Insull himself in voting control. Besides Insull, the directors nearly always included his son, Samuel Jr.; his younger brother, Martin; two close financial advisers, Harold Stuart, his bond underwriter, and Walter Brewster, who handled stock issuances; plus a handful of key financial and engineering executives.

The holding company evolved as a favored form of organization because as an investment company, it did not fall within the reach of utility regulators. Eminently sensible regional power arrangements, for example, could not be accommodated by state-based regulation. But a holding company could assemble contiguous state-regulated companies in a pattern that made economic sense and contract to provide common generating, construction, and financial services. By the mid-1920s, as the basic utility infrastructure was being built out, the smart money was shifting from building competing operating companies, to buying and selling shares in holding companies.49

Insull had entered the holding company fray almost as an afterthought. His flagship Chicago and Illinois utilities were independent operating companies. But in his early career, he was often called upon by bankers to reorganize troubled utilities, and in 1902, to test the skills of Martin, he gave him one such assignment in Indiana. Martin turned out to be a brilliant, aggressive, if possibly risk-prone, manager, and by 1911 he had consolidated a swath of disparate companies into an attractive Midwestern franchise. Insull decided that he wanted to keep them, and a board member suggested the idea of a holding company. That gave birth to MWU in 1912, which by the mid-1920s, was the largest entity in the Insull group.

While the stacked pyramid of holding companies made excellent management and financial sense, it also opened the door to dangerous financial leverage. In Insull’s case, by the time his pyramids imploded, his leverage (the ratio of borrowed money to cash equity) had ballooned to a highly dangerous 2000:1 (see the Appendix for details).

Insull had a mixed record as a holding company operator. On the positive side, his overhead charges were barely a tenth of those of other pyramids, like Electric Bond and Share Company, a Morgan controlled entity and a notorious cash stripper. (One of the attractions of holding company pyramids was that it was difficult for regulators to track the overhead fees through the multilayered corporate structures.) In the final days of his company, of course, when Insull was caught in a death-grip cash squeeze, he was as diligent as any other big operator in sniffing out pockets of cash to stave off his bankruptcy. Insull also gets credit for not—at least not until very late in the game—engaging in extreme pyramiding; even a very hostile post-Crash federal investigation commented that the use of pyramiding in the Insull group was “at a comparatively modest scale.”50

On the other hand, Insull took full advantage of opportunities of the holding company structure to manufacture profits. Favorite gambits were trading illiquid securities between controlled entities at artificial values, accounting for stock or rights-based dividends, and depreciation accounting (see the Appendix for details).

Insull’s tragic flaw may have been his infatuation with his legacy. He wanted to found a dynasty, even though his son, “Junior,” a diligent and intelligent young man, was not of the same mettle as his father. A perfect retirement occasion came Insull’s way in 1926, when he was sixty-seven. He had played a major role in laying out the plan for a modern British electrical grid, and was sorely tempted when the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, invited him to return to his home country and head the effort to create the system. Junior had been ambivalent about committing to the company, and had Insull taken Baldwin’s offer, he would have had to devise a more permanent, less family-oriented management structure. But first he consulted Junior, who told him that he now wished to inherit the dynasty.51

Insull was well aware that MWU was a cash sink. It required accounting gimmicks of all kinds to produce even a modest layer of reported earnings. Federal auditors found that its 1928 statements, for instance, were overstated by about $10.8 million. The biggest cash drain was the hefty dividends on a small mountain of preferred stock. Sometime in early 1929, Insull and Stuart developed a plan to refinance all the MWU outstanding preferred shares with a new security flotation of $145 million. That would buy out all of the preferred and provide an additional $20 million in free cash. There would be a preferred issue for $52.5 million, carrying a 6 percent dividend payable at the holder’s option either in cash or rights to purchase common at highly favorable prices, and a common issue for $92.5 million, with all dividends in the form of stock purchase rights. This was very much a bull market offering, built on the premise that most investors would treat stock purchase rights as a superior currency to cash. If all investors chose the stock rights alternative, the cash flow savings would be $9 million a year.52

But there was a problem with the pricing. For the deal to work, the “highly favorable” price for converting the preferred to common had to be at least $200/share. But recent price slippage in MWU stock put them in a trading range well short of $200. (Investors presumably understood that MWU was a much dicier proposition than the three Chicago and Illinois flagship companies.) It was common practice in those pre-Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) days for investment bankers looking to sell an issue of common stock to first organize a pool to push up the share price. Insull’s market operators therefore began a quiet purchasing and selling campaign under a variety of brokerage names, mostly with cash borrowed from banks. Within a month, MWU’s stock price had jumped from 181 to 308. By comparison, the Dow Industrial index gained only 4 percent in that same month, while the Utilities index grew only by 6.5 percent. The rapid run-up in the share price generated its own momentum. Without any additional purchasing by the Insull pool, within another couple of weeks, the stock shot up to 364 by July 27. When Insull announced the refinancing a couple of days later, the stock hit a high of 492. A month later, when a broad distribution syndicate for the issue was announced, it went to 550.

The timing was awful. That glittering 550 price came in September 1929. Within a month, MWU shares slipped to $185. Heroic buying by the underwriting syndicate pushed them back to the 250–300 range. But the shares had been sold mostly by subscription, with monthly installment payments over a ten-or twelve-month period. As stock prices wavered, a number of subscribers defaulted, with their subscriptions being picked up by the syndicate, often with Insull companies stepping in as the buyer of last resort. Given the gyrations in the MWU stock price, of the shareholders who paid their subscriptions, nearly all opted for cash dividends. Add in the heavy bank debt incurred during the refinancing operations, and the whole exercise might well have increased the cash drain.53

The disappointing MWU refinancing was a double blow, for Insull was deeply worried about maintaining control of his companies. Sometime in 1928, Insull became aware that a shadowy combination of brokers and investors were building substantial positions in his three Illinois operating companies, which he considered an existential threat. With a little sleuthing, he learned that the combine was headed by Cyrus S. Eaton, a senior partner in Otis and Company, a Cleveland investment bank, as well as chairman of Continental Shares, a big investing and acquisition vehicle. Insull knew Eaton, but their relations were “never of a confidential character.” He was a Canadian, forty-five years old in 1928, who had once run a modest gas utility for the senior John D. Rockefeller. He had taken a liking to the utility business, and moved to the United States to build a portfolio. Quiet and shrewd, by 1928 he controlled about $1 billion of gas and electric utilities, and had become enamored of the opportunities in the Chicago region. That same year, Insull and Eaton ran into each other on shipboard returning from London, and spent considerable casual time together. Since Eaton never mentioned his interest in Insull’s businesses, Insull’s threat antennae went on high alert.54

In earlier days, when Insull stock was still fairly closely held among customers and local investors, the tight insider director network made Insull’s control position almost impregnable. But with a $3 billion capitalization, and national distribution of shares, a canny operator like Eaton could easily build a sufficiently large block of shares to cause no end of trouble. Insull’s worries were magnified by his dynastic ambitions: a strong nonfamily ownership presence was likely to object to handing the company over to Junior.

Insull’s defense strategy was to create a super holding company to acquire large blocks of shares in the Insull properties by buying them on the open market. Insull Utility Investments (IUI) was formed in December 1928. A year later, to fix a technical glitch,* Insull created a twin company, Corporation Securities Company (CSC) of Chicago, with the same mission. As Insull explained in his IUI announcement:

I have felt for some time past that, in the interest of the various properties with which my name is associated, there should be some rallying point of ownership and friendship. So after consultation with my son and my brother, Mr. Martin Insull, and other members of my family, I decided to form an investment company to buy and hold securities generally, but more particularly to buy and hold the securities of the several companies with which my name is associated.… Such was the purpose for the forming of Insull Utility Investments, Inc. I wanted it, for all time, to be interested in the properties that it has been my privilege either to create, improve, or develop, and I thought I could trust the board of directors with the name of “Insull,” that is of more consequence to me than anything else in the world.55

The IUI shares opened on the public exchanges in January 1929, almost perfectly timed for the wild run-up in the stock market. The Insull reputation was golden, and the new holding company looked like a money machine. By late summer, IUI shares had rocketed from $15 to $150. Between them, IUI and CSC took blocking positions ranging from 17 to 29 percent in the three Illinois operating companies, as well as a 28 percent share in MWU.56

Eaton waited until April 1930 before disclosing his intentions, using an intermediary, Donald McLennan, who was a cofounder of the Marsh & McLennan insurance combine, a friend of Eaton, and a director of Commonwealth Edison. By that time, Eaton had shifted most of his attention to steel: the previous December, he had announced the merger of a number of steel companies around the Great Lakes into Republic Steel, creating the third largest steel producer in the country. Insull was in London when McLennan made his probe, and after a great deal of cable traffic, Eaton, Insull, and their retainers met in early May 1930. Eaton, as Insull must have known, was under considerable pressure. He had been working assiduously to add the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company to his steel combination, but Bethlehem Steel had just muscled its way in as a suitor, and Eaton needed to shore up his liquidity for a bidding war.57

Famously, Eaton opened the meeting by proposing a combination of the Insull and Eaton utility holdings. In Insull’s account, “Mr. Eaton… assured me… that as long as I was in control of the management of the three operating companies, any stock that he represented would be voted for me.” Insull’s biographer, Forrest McDonald, based on the notes taken at the meeting, and extensive interviewing of still-living attendees, calls this an “offer… to consolidate all his holdings with those of Insull, under Insull’s exclusive management, no strings attached.” Even assuming that is what Eaton said, it is hard to believe. It is true that Eaton didn’t manage any of his acquisitions, and that he genuinely admired Insull. But he was an activist investor, a prototype of, say, a Carl Icahn, and his hands-off promise would be good only so long as the companies prospered. Tom Girdler, Eaton’s hand-picked chairman of Republic Steel, said that other steel company executives “were simply scared to death of Eaton.”58

Insull wasn’t interested in a combination, and offered to buy all of Eaton’s holdings—160,000 common shares distributed among the three target companies, with just over half of them in Commonwealth Edison. The offer was for $56,000,000, or $350 per share, about a 12 percent premium to the current market. (Insull share prices held up well during the first stages of the crash.) Eaton wanted $400 a share, and threatened to create an investment banking syndicate to sell off the shares to any comers, which played on Insull’s aversion to allowing the big New York banking houses gain a foothold in his business.59

Negotiations broke off at that point, but McLennan continued to advocate for a deal, and finally, in June, Insull agreed that he would purchase all of Eaton’s stock, at the $56 million price, payable $48 million in cash and $8 million in the common stock of the two holding companies, IUI and CSC. Stuart was in London, and Insull pointedly did not inform him of the deal in advance, since he would have objected to any such commitment prior to locking up the financing. The terms were agreed on June 2, and the deal closed on June 9. IUI and CSC were each obliged for half the payments. While the stock transferred immediately, the cash was paid in three installments, $10 million on closing, $14 million on July 9, and $24 million on October 9.60

It took considerable scrambling to marshal the cash. Between them, IUI and CSC took out short-term bank loans to cover $7.25 million of the $10 million first installment. For the July 9 payment, IUI borrowed $28 million from an MWU $50 million gold note flotation, and used half of it for the Eaton payment, and most of the rest to pay off bank loans. The $24 million final payment due October 9, 1930, was daunting, since a first $10 million installment payment on the MWU gold note was coming due, and there were no more available MWU gold note proceeds.61

Insull tried to raise the final installment in the public markets, but a summer offering of 600,000 IUI common shares priced at a substantial discount fizzled. CSC ended up taking nearly half the issue, which avoided embarrassment, but produced no new cash. In August, Halsey, Stuart and Company attempted to syndicate $40 million in CSC gold bonds, but the tepid market forced a reduction in the offering to only $30 million. To make up for the shortfall, Insull borrowed $10.25 million from a consortium of banks, including, to his chagrin, several New York banks. To scratch out more collateral for loans, Insull bulked up IUI’s balance sheet with $16.6 million of Insull company shares, purchased from one of the group’s employee benefit funds. The payment was at market value, but the consideration was a goulash of new IUI shares, “assumptions of obligations,” and other paper, but only $5.9 million in cash.62

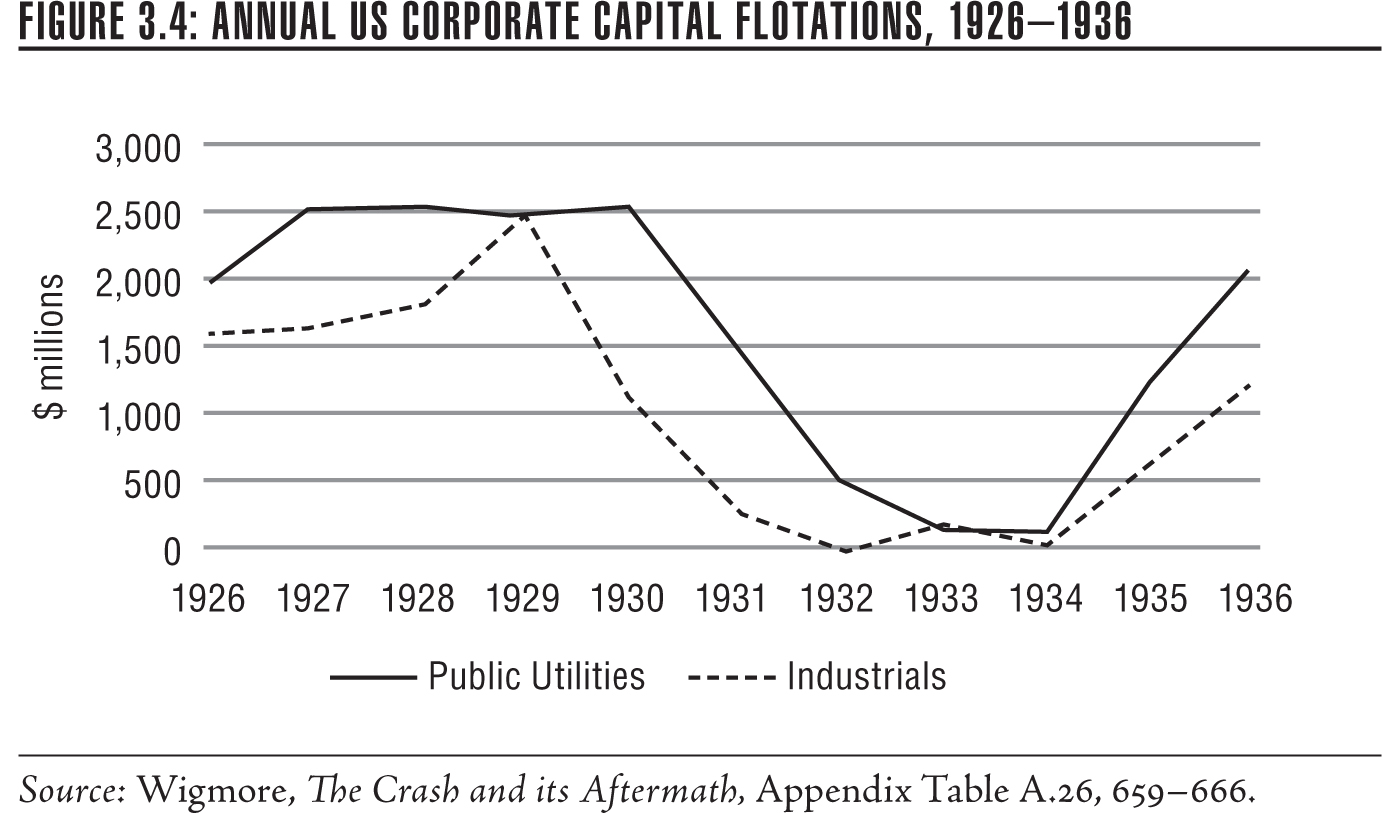

By such expedients, the final payment to Eaton was made on time. Eaton was a considerably richer man, while Insull was left under a severe cash strain. To make matters worse, the prices of Insull securities were dropping rapidly. Although Insull stocks had basically held their prices during the first half of 1930, the second half was a disaster. IUI and CSC taken together closed their years with an unrealized market value loss of more than $100 million. Euphoria briefly returned when good yearend earnings reports created a bounce-back to early 1930 prices. It was a mirage. Public utilities continued to outperform industrial companies, but as the Depression ground on, Insull shares were on a relentless downward slide.63

The long American boom that had started in 1923 had dimmed memories of difficult times. And Insull had had a smoother ride than most. Even during the banking crisis of 1907, he had ready access to the London money market. He hadn’t blinked at the big cash commitment for the Eaton purchase because the public markets adored his securities. By late 1930, however, capital markets were firmly closing to even the most blue-chip borrowers—even to Insull.

MWU, IUI, and CSC went into receivership in April 1932. Between them, they had $84.1 million in bank debt, almost all of it in demand notes, and all of it requiring collateral of 150 percent of outstandings, or about $120 million. Since all three were holding companies, their primary assets were shares in other Insull companies. MWU held securities with a book value of $299 million, about three-quarters of it in Insull paper; the receivers marked its recoverable net worth down to $30.9 million. IUI’s book value was $259 million, again almost all in Insull securities, which was marked down to $27.5 million. CSC had a book of $142 million, which was valued at $13.3 million. Forrest McDonald seems to fault the banks for not seeing Insull through, but they had no choice—$84 million was a lot of demand loans, especially without collateral. The economy did not tick up until a full year after the Insull companies entered receivership; the public markets remained tightly shut until 1934, and didn’t truly recover until 1936.64

A number of smaller Insull companies followed the big three into bankruptcy, but with few exceptions the operating companies survived handily. One study shows that of 120 Insull companies with securities held by the public, only 23 lost any appreciable amount of money, and most of them were intermediate holding companies or trading subsidiaries. Commonwealth Edison bonds, for example, never dropped below 90, and all were paid off on schedule. Even the great majority of the MWU operating companies—which, in the last days of Insull’s struggle for solvency were stripped of almost all their cash or salable securities—survived intact without service interruptions or other calamities. The losers were primarily financial players and naïve investors. Power customers saw little disruption. A careful 1962 analysis suggests total losses to the public of about $634 million, or about a quarter of the 1929 capitalization.65

Insull would almost certainly have survived if he had resisted the Eaton purchase. Virtually the entire cash payment, whether at first or second remove, was financed by impatient demand-note bank debt. Fending off Eaton was also a prime motive for the formation of the two investment companies, IUI and CSC. Taken together, they issued $81 million in gold bonds and debentures and $206 million in various preferred and common shares. The bonds and debentures all defaulted after just a few payments, and the shares were pure water. Absent the investment companies, Insull might have followed a more cautious path in the MWU refinancing, spurned the Eaton probe, and managed his cash position more vigilantly. The Depression was hard on everyone, but the core of the Insull system was strong enough that it should have survived with its stellar operating record intact.

Insull was summarily removed from operating control of his companies in early June, not quite two months after the first receiverships. He quietly sailed to Europe, even as pressure built for criminal trials in the United States. Junior visited him in Paris in the fall, and suggested that he stay abroad in a country without extradition treaties until the blood-lust for his scalp abated. Insull chose Athens, where a court had ruled against extradition, and he spent much of a year laying out a modern electrical power plan for the government. The new Roosevelt administration pressured the Greeks to give them Insull, to the point where Insull embarked on a freighter to seek asylum elsewhere. At American prodding, however, the freighter made a “repair” stop in Istanbul, where the police took him into custody for extradition. When he was arrested in America, he couldn’t make bail until friends passed the hat. 66

Insull went on trial in Chicago in October 2, 1934. It lasted six weeks. Almost every offense charged involved detailed issues of accounting and disclosure, that even the prosecutor’s team, not to mention the jury, often had trouble getting right. Charges that Insull had engaged in large-scale embezzlement hardly squared with the fact that he had almost no money; his entire fortune was in Insull holdings, and he probably lost more than any individual investor. The chances of conviction, however, still seemed good—juries were not in a mood to give tycoons a break. But on the first day of November, Insull took the stand and “wove a spell” around the jury, explaining what he had done in Chicago, the intriguing technical issues, the shift to steam turbines, his mastering of the economics of the business, his sadness at the ending. The case went to the jury two weeks later. As soon as they had been sequestered, the jurors took a poll and found that they were unanimously for acquittal. For form’s sake they lingered in the jury room for two hours, so they wouldn’t be accused of being bribed.

Insull had two more trials—one in Washington, DC, alleging embezzlement by him and Martin, in which they were quickly acquitted, and a federal proceeding, in which the judge directed a verdict for Insull after hearing the prosecutor’s case. Insull returned to Paris, where he lived quietly and thriftily. In July 1938, he was found dead in a Paris subway, apparently the victim of a heart attack.

Insull was a great entrepreneur, and by no means a crook—though for 1920s financiers, noncrookedness was not a high bar. The intercompany churning of thinly traded securities to generate ersatz mark-to-market profits was deceptive, as was the skew of income statements toward noncash earnings. The understating of depreciation, or the shameless bulling of the MWU stock price to ease its refinancing were all crass attempts to mislead investors. Some of the accounting gambits were practiced so assiduously that they might have supported a common law charge of fraud. But the Insull group was hardly the only conglomerate that engaged in such practices—the Pecora hearings disclosed roughly similar practices at most of the major banks.67 Accountancy was very much in a state of flux: the definition of generally accepted accounting standards had to await the New Deal security markets reforms. Quiet syndicates formed by insiders to bull share prices was something that gentlemen did. The Arthur Young accountancy had signed off on all of the gambits employed by the Insull group.

A final note of poetic justice. Cash-rich after his deal with Insull, Eaton engaged in a grueling two-year-long battle to become a top-tier player in the steel industry, and ended up losing everything. Continental Shares, his primary acquisition vehicle, was a publicly traded investment company; today we would call it a private equity fund. Founded in 1926, it was capitalized at $150 million, and was widely held. Eaton seems to have learned how to ruin a company at Insull’s feet. Having overextended himself in his steel wars, Eaton resorted to heavy bank loans collateralized by his stock holdings. By June 1932, the Continental Shares stock price had fallen from $78 a share to just 25 cents, and the bank creditors wound it up some months later. In 1932, however, Eaton was only forty-nine, and unlike Insull, had time for a comeback. He quietly resumed his banking activities in 1938, and in 1961, Fortune listed him as one of America’s top tycoons, with a multibillion empire in mining, steel, and banking, and a personal net worth of $100 million.68