VII. THE TWILIGHT OF THE GODS II: KREUGER

VII. THE TWILIGHT OF THE GODS II: KREUGER

Ivar Kreuger, the Swedish “match king,” committed suicide on March 12, 1932, within a few weeks of the collapse of Insull’s empire. Kreuger’s death left his murky collection of hundreds of companies in dozens of countries to the tender mercies of receivers. The final report, prepared by the accounting firm Price Waterhouse, was scathing:

We do not think more need be said about these published accounts except that the manipulations were so childish that anyone with but a rudimentary knowledge of bookkeeping could see the books were falsified.… Entries in its general books were palpably false, few entries even looking reasonable on the surface. 69

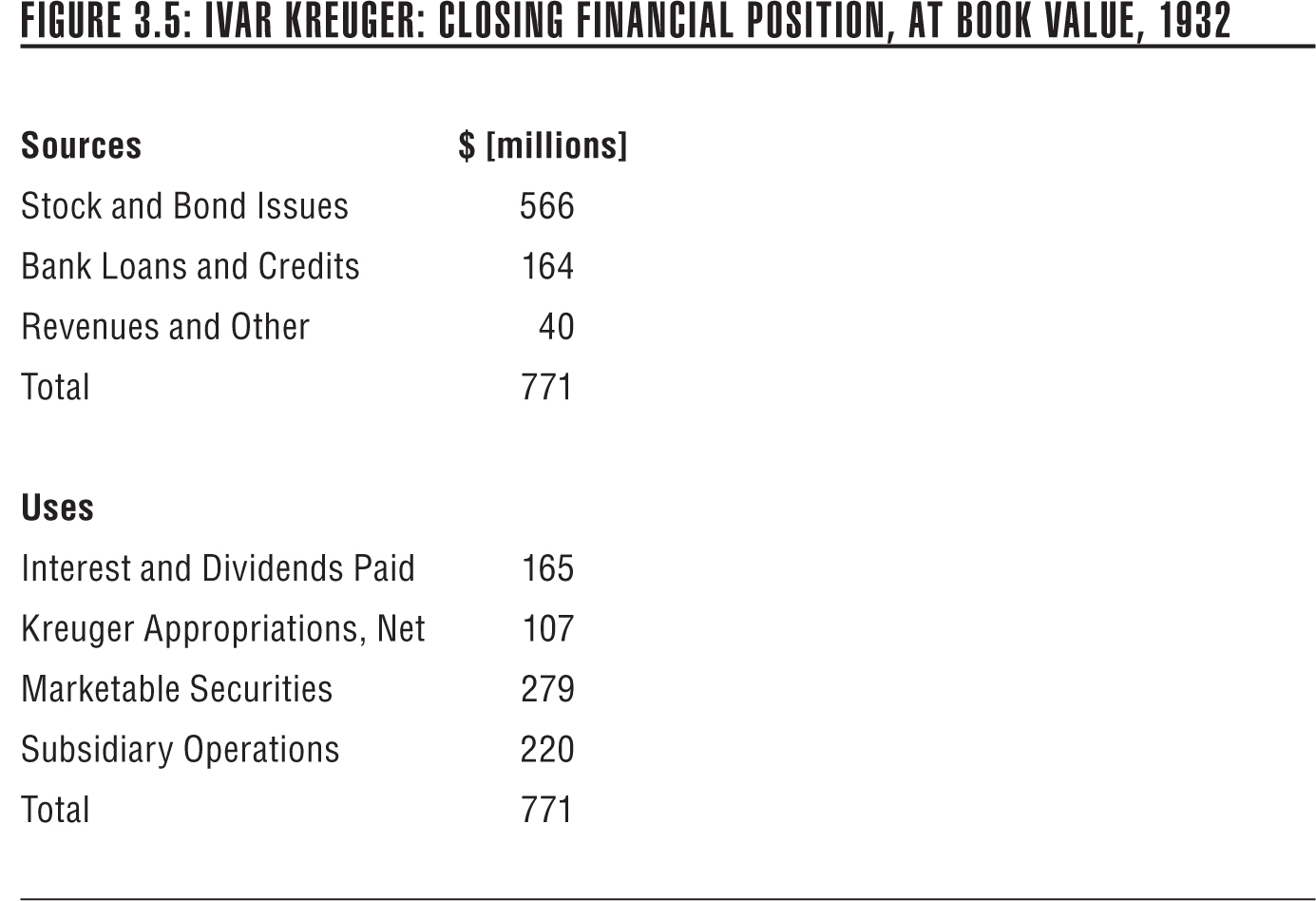

Childish the Kreuger books may have been, but from 1918 until its collapse, Kreuger had raised $771 million, with the sources and dispositions at book value as shown in Figure 3.5.70

At fair market values, the Price Waterhouse team estimated that available assets were impaired by $250 million, or about 30 percent of its stated book value. As a Price Waterhouse partner explained it to a Senate investigating committee:

Company A may show that it has received 200,000,000 kroner of earnings which are fictitious. Out of that it pays a dividend to another company. And that company receives it in cash, possibly, and has no good reason to doubt that it has perfectly good earnings in its hands. But when you trace the whole chain you will find that that 200,000,000 kroner is probably a return to it of 200,000,000 kroner that it paid for an investment in another company possibly as an income that comes out of another company as a dividend.71

The report revealed that “serious irregularities had extended back for at least 15 years,” that “large sums of money had been appropriated and concealed,” and that “fraudulent practices assumed large proportions in 1923 and 1924 and continued thereafter.” Such frauds were possible, they concluded, only because of:

(1) the confidence which Kreuger succeeded in inspiring, (2) the acceptance of his claim that complete secrecy… was essential to the success of his projects, (3) the autocratic powers which were conferred upon him, and (4) the loyalty or unquestioning obedience of officials, who were evidently selected with great care (some for their ability and honesty, others for their weaknesses).72

Ivar Kreuger was a strange compound of business titan and confidence man, and could have been a success in either persona. He was born in 1880 to a large Swedish family headed by a minor executive in a match factory. By the time he reached young adulthood, Ivar was physically imposing with an arresting personality, able to hold forth on almost any topic in five languages—and still come off as self-effacing. No one could have guessed that his easy charm was the product of many hours preparing material for social events, and studying the people he wanted to impress. The brilliance wasn’t faked, but like a professional athlete, he assiduously polished his talents to the highest sheen and displayed them with the instinct of a showman. When conducting major business negotiations, Kreuger almost always appeared without lawyers or accountants, without papers or notes, exhibiting casual mastery of every nuance of a business, every number in a pile of balance sheets, waiting serenely as his counterparties fumbled through their files to stay abreast.73

He was a legitimate millionaire by his early thirties. After graduating from engineering school, Kreuger went to America to learn modern skyscraper engineering. Talking his way into a low-level position with Manhattan’s largest construction company, he worked on the Macy’s building, the Metropolitan Life tower, the Flatiron Building, and the Plaza and St. Regis Hotels, along the way spotting and fixing critical flaws in the building’s designs and techniques. He moved to South Africa to work on the Carlton Hotel, then the world’s largest building, and later briefly joined the Transvaal militia, before embarking on a “multiyear bender” through a large swath of the world. Returning to Europe, he formed a shoestring partnership with an architect, Paul Toll, in a highly successful design and construction business, working throughout Europe. Their major selling point was guaranteed on-time performance, with heavy penalties for failure. Toll was a fine architect and Kreuger a master salesman whose American experience had given him a thorough grounding in modern construction management. The business was a resounding success, and the two quickly built an international practice, including in the United States, where they built the prize-winning football stadium at Syracuse University.74

A Swedish banker, impressed with the success of Kreuger & Toll, offered to back them in any business of their choosing. Kreuger picked matches, while Toll opted out, choosing to work full time on the firm’s construction business. Matches were something of a Swedish specialty because of their abundant forests, and Swedes had invented the strike-on-the box safety match. Employing tactics both fair and foul alike, including “sweetheart” deals with the government, Kreuger crushed his competition and created a Swedish match monopoly that at least appeared to be making a steady profit. His model, he frequently said, was John D. Rockefeller’s oil monopoly. Matches and oil, he argued were low-margin businesses that could become profitable if and only if one could control the entire market.*75

Kreuger made a trip to the United States in 1922, to sound out the prospects of creating a US match monopoly, and was disappointed to discover that Americans did not favor monopolies. But he realized that no country could rival the United States in capital raising capacity, so he decided to raise American capital to finance match monopolies abroad. In conjunction with the investment banker Donald Durant, of Lee, Higginson, Kreuger worked out a strategy of raising money on Wall Street to finance cash-desperate governments in return for long-term match monopolies. It was sweet music to Lee, Higginson partners. Their firm was an old Yankee establishment that yearned after a presence in international lending, then dominated by the Morgan bank.76

Lee, Higginson arranged an informal road show for Kreuger, exposing him to a broad segment of the financial community—and he wowed them, with his vast frame of reference, with his diffidence and apparent modesty, with his intimate knowledge of European corridors of power, but most of all with the regular 25 percent dividend paid by his holding company, Kreuger & Toll, and the 12 percent dividend paid by his manufacturing company, Swedish Match. It was an easy step from there to a $15 million dollar gold debenture floated by a new company, International Match, controlled by Ivar Kreuger. It was money that Kreuger badly needed. Parts of the whopping dividends paid out to investors were paid from bank loans, and the banks were dunning him for repayment. His match operations were running losses, but he had hidden them in off–balance sheet “investment” accounts.77

Kreuger had carefully prepared for his American windfall by setting up a circle of companies in Sweden, Switzerland, and Liechtenstein, and then creating a string of accounting entries to spirit the $12.2 million net proceeds of the American flotation into the dark recesses of a secret Liechtenstein entity—Continental Securities, with a single employee dedicated to doing exactly as he was instructed by Kreuger. Kreuger diligently avoided consolidating the accounts of his companies and spread financial reporting among multiple national jurisdictions. His cover was almost blown at the very start. Well before the American debenture sale, an accountant from the Swedish Bank Inspection Board had figured out what Kreuger was up to and wrote a damning report. Amazingly, the Swedish banks who were lending to Kreuger, and making substantial profits from his stream of dividends, collectively buried it.78

Match monopolies were old hat in Europe. France had created the first, in 1872, and at least a dozen countries had followed suit. Although Kreuger easily enamored American investors, in the real world in Europe he faced a host of entrenched politically connected competitors. His first breakthrough came in Poland. Its government was chaotic, and the finance minister was desperate for a western loan. The official terms of the Polish deal were that the government would grant Kreuger a match monopoly in return for a $6 million loan that carried an interest rate calculated to equal the royalties expected from the match monopoly.79

But there was also a secret deal, by which Kreuger promised to deliver the Polish government $25 million, at a usurious 24 percent interest. That deal was closed in July 1925, and it required that the $25 million be disbursed in two tranches, one of $17 million in October, and a second for $8 million the following July. The contract also provided that the match monopoly would be administered by a new Dutch company, Garanta, controlled by Kreuger, but with Polish representation. Garanta, like Continental Securities, was intended as a black hole, an invisible cash sink solely at his disposal. Kreuger had actually used much of his first Lee, Higginson underwriting to speculate on foreign currencies, and had done quite well. Later he had taken big losses, but covered them by transferring them to Garanta. That didn’t help his cash flow, but it placed the misadventures beyond the reach of pesky accountants.

Even Durant, who usually acted as Kreuger’s enabler, had problems with the second Polish deal, because Kreuger refused to show him the contracts or explain how they worked. But Kreuger’s reputation as a financial magician was rising on Wall Street, in part because of use of groundbreaking financial instruments—securities that morphed between debt and stock, or had special dividend rights or conversion rights, or embedded options. They may have been mostly worthless, but investors loved them, especially when they didn’t understand them. But they always included highly favorable terms for the issuer and its bankers. Just the kind of instrument that makes investment bankers smile. Durant swallowed his doubts, and yet another Kreuger placement, managed by Lee, Higginson, went on the market at a premium—and sold out in a trice. Poland got its $17 million first installment, and the thumpingly high interest payment was duly received every quarter at Garanta. Kreuger’s legend grew.80

Durant was entitled to his doubts. For all he knew, Kreuger might have simply invented the second Polish deal and plunked the offering proceeds into the recesses of Garanta at his own disposal, using part of it for speculation and the balance to pay the interest, while counting on future raises to pay off the principal. By this time, Kreuger had thoroughly suborned the Ernst & Ernst accountancy manager who supervised the group’s audits. He never pressed for detail on Kreuger’s secret companies, and on his own motion occasionally changed financial reports to comport with previous claims by Kreuger.81

By 1927, Kreuger was a renowned mogul. His match operations extended around the world, and he was the major producer of match machinery. As International Match’s stock price rose to the stratosphere, he used it as a cheap currency to buy businesses throughout the globe—in mining, real estate, timber and paper products; a big stake in L.M. Ericsson, the Swedish phone giant; even in the film industry. It was Kreuger who discovered Greta Gustafsson in a hat shop, and helped her become Greta Garbo. While he was something of a health nut, and abstemious in food and drink, he lived lavishly, with large apartments in major cities, always staffed and prepared for a flying visit. He liked fast cars and boats, and built a stunning headquarters in Stockholm named the Match Palace. After the early death of a childhood sweetheart, he never married, but apparently had discreet liaisons with several charming and talented young women.

But he never lost his confidence-man instincts. When Percy Rockefeller, one of old John D.’s nephews and a director of International Match, visited Kreuger in Stockholm, he was given a lavish party at the Match Palace with a substantial fraction of the European ambassadors in attendance. Rockefeller was duly impressed, and reported to fellow directors that Kreuger was “on the most intimate terms with the heads of European governments,” and that they were “fortunate indeed to be associated with” him. The “ambassadors,” however, were actors, carefully rehearsed to dazzle innocents like Rockefeller.82

If any single deal catapulted Kreuger into the global business stratosphere, it was the theft of French bond business from under the nose of the Morgan bank, who had treated European finance as a family heirloom. Raymond Poincaré had just been reinstated as the prime minister of France, and was desperate for money. France already owed the Morgans $100 million, at 8 percent interest. Poincaré and Kreuger were friends, however, and they worked out a plan for a massive $75 million loan from International Match with a forty-year life at only 5 percent interest, plus a stream of revenues from a new French match monopoly. The actual proceeds to the French would be $70 million, with $20 million coming from International Match reserves and $50 million from placing a typically innovative Kreuger hybrid bond. The securities Kreuger sold in America went out at 98.5, which gave him a $2.5 million margin over the money he delivered to France. In addition, at payoff, the French would owe $75 million, not $70 million, which was more potential margin for Kreuger. One hitch was that the French socialists objected to the monopoly—it would have disturbed a politically connected monopolist already in place. Kreuger nimbly changed it to a monopoly on match equipment sales in France, priced at a premium that would produce about the same income.83

Kreuger struck another blow at the Morgan empire in the summer of 1929, by committing to make a $125 million loan to Germany, subject to a fifty-year match monopoly and German participation in an international debt-restructuring process. Jack Morgan was shocked to see that Kreuger had winkled the biggest international financial transaction in history from under his nose. Germany promptly met all of Kreuger’s conditions, and Lee, Higginson pointedly excluded the Morgans from the securities syndicate.84

Kreuger’s German-linked bonds went to market in the fall, just as markets were turning unusually skittish. Durant was confident that Kreuger-sponsored securities would always sell, because of the magic of the name, but he thought that any further placements would have to be delayed until the markets recovered. The Kreuger sale was closed on Wednesday, October 23, the day before Black Thursday—the first day of the dizzying crash in stock prices and the occasion of the ultimately unsuccessful intervention by Richard Whitney and the bankers’ pool. The bankers in the Kreuger syndicate had a collective attack of angina. Although they had already received customer commitments for the securities, they expected widespread defaults. Kreuger-sponsored securities went out only on a “firmly underwritten” basis. The bankers had already written their checks, and would end up swallowing whatever amount was left unsold.85

Ironically, this was the same week that Time featured Kreuger on its front cover, reporting breathlessly that when two US visitors missed seeing “the countryside aglow with Sweden’s famed roses,” Kreuger invited them to one of his country houses, which displayed “everywhere rosebushes in full bloom”—supplied just for the occasion from a Stockholm hothouse. The encomium ended with a quote from the match king: “There is not a single competitor with sufficient influence upon the different markets to cause us any really serious harm. No market is sufficiently significant to be of importance to us. The reason is that the whole world is our field.”86

The stock market was closed the Friday and Saturday after Black Thursday—in the mostly paper-and-pencil accounting environment, the day’s price swings had left a mountain of incomplete transactions to work through. To this point, Kreuger had been mostly incommunicado, while affecting a Zen-like calm with his closest associates. He broke his silence on Friday afternoon, with a cable to Lee, Higginson:

I am very sorry that our issue seems to have come at a very unlucky moment. We are very anxious that the syndicate… will not have reason to regret their action, and we are also anxious not to overload the American market with our paper. We have therefore arranged with a Swedish syndicate to offer to take over, on December 31, 1930, up to half the amount of such debentures as the American syndicate has acquired. This will be done at the acquisition cost to the American syndicate. We expect to receive notice no later than December 15, 1930, of the extent to which the American syndicate wishes to avail themselves of this offer.87

The bankers swooned. Durant announced the offer to the syndicate, adding that it “is without precedent… [and] shows conclusively the breadth of the man.” Virtually all the syndicate members rushed to assure Durant of their intention of holding on to the securities, as Kreuger knew they would. The offer, indeed, should be in the Hall of Fame of market ploys. In effect, it was a free putback at their own price, and the offer was good for more than a year. Since the overwhelming sentiment on Wall Street was that the market would quickly recover, there was little risk in waiting, and a quick putback might cost them potential profits. The calmness, the “almost casual” way the offer was framed, added to the effect. Kreuger, investors believed, had nearly unlimited resources—how else could he outbid Jack Morgan for major country bond business? The syndication was for only $28 million, half of that, to the Kreuger of the carefully crafted legend, was chump change. In fact, at the end of 1930, when he was very hard up for cash, Kreuger had to pay $4.4 million in put settlements. Characteristically, he sent Durant $5 million to settle the accounts, and told him to hold the extra $600,000 for the time being, since he “didn’t need it.”88

Some bankers, not least at the Morgan bank, wondered how Kreuger could dispose of so much money. Yes, he controlled perhaps two-thirds of the world’s match industry—his strategy of buying monopoly privileges from national governments had been very successful. But matches were a low-margin business, and his global sales were almost certainly less than $150 million. Stripping out misleading items, like “profits” that were just dividends paid by one company to the other, his match companies still reported $30 million in clear profits, which would have required a 20 percent headquarters margin on global sales, which should have been impossible. When pressed on the issue, Kreuger airily dismissed it. Of course matches didn’t earn that much, he said, but both the match companies had large investment portfolios and had done very well on “speculations.”89

Bravado aside, Kreuger was facing an August 1930 first installment of $50 million on his German loan, and however he scraped or scrambled, he could not come up with that much money. But there may be special gods who look after the truly bold. Poincaré lost his premiership amid an upheaval in the French government, even as France enjoyed a sudden economic boom. The new government decided to repay the Kreuger loan, all $75 million, in April 1930, earning Kreuger a $5 million profit—the difference between the $70 million proceeds to the French and their repayment obligation.90

With splendid business-as-usual aplomb, Kreuger delivered the promised $50 million to Germany, and announced, in addition, that Kreuger & Toll’s dividend would be increased from 25 percent to 30 percent. A respected investment newsletter recommended Kreuger securities as “sound” with “possibilities of appreciation.” Time magazine noted that Kreuger had a government loan portfolio of $315 million, and had just added seven new match monopolies to his stable.91

In fact, Kreuger’s long string of successes was running out. The Price Waterhouse accountants, who performed the postmortem on Kreuger’s financial empire, accused him of running a “Ponzi game.” Frank Partnoy, the author of an outstanding Kreuger biography, took issue with that characterization, because the original Ponzi gambit was pure swindle. Charles Ponzi made no investments, but simply used proceeds from new investors to pay glittering returns to previous ones. Kreuger, Partnoy points out, had vast earning assets—highly productive iron mines, excellent factories for both matches and match-making equipment, vast timber holdings, extensive real estate in Stockholm, and major security holdings, including a controlling interest in the Ericsson telephone enterprise.

Kreuger’s problem wasn’t so much the scale of his assets as the inadequacy of his cash flow. The economist Hyman Minsky defined “Ponzi finance” as a state when a company’s cash flows are such that it must either borrow or sell assets to pay both interest and principal on its debt. The name is justified because both the original Ponzi game and versions like Kreuger’s require ever larger borrowings just to stay ahead of their debt service. Absent some dramatic windfall, the firm indulging in Ponzi finance must eventually fail.92

In Kreuger’s case, the walls were closing in. He sold his controlling position in Ericsson to America’s International Telephone and Telegraph (IT&T), dazzling the assembled bankers and advisers on the IT&T side with one of his patented solo-with-no-notes negotiating marathons. The proceeds were $11 million, which Kreuger desperately needed to meet an interest payment on one of his debentures. Some months later, however, the accountants for IT&T caught an important misstatement in Ericsson’s cash reports—which Kreuger surely knew about—and Jack Morgan, IT&T’s banker, nixed the deal, with considerable glee one imagines. Kreuger humbly agreed to return the $11 million. The strain on Kreuger was becoming evident. He had always been attentive to his health, getting regular exercise, cultivating calmness. Now he was drinking and smoking heavily, losing his temper, railing at his closest subordinates. He seems to have been acutely aware of his deteriorating mental and physical health, and went to great lengths to avoid personal meetings, often locking himself inside a personal inner sanctum he called his “silence room” for days at a time.93

His behavior after losing a hoped-for contract for a match monopoly shows his desperation. Kreuger had a trusted printer forge £21 million worth of Italian treasury bonds, and Kreuger himself forged the signatures of the Italian officials. He used them only once. In 1931, when he was badgering Lee, Higginson for yet another bond flotation, they asked for documentation of the “$77 million” in securities he claimed to have in one of his (by now semi-) secret companies. He invited an accountant into his vault, pulled open the drawer with the faux bonds, and got his deal done.94

By 1931, Kreuger had been playing a Minsky-style Ponzi finance game for a long time. While he had a great many businesses besides matches, the majority were commodity, low-margin businesses, like ore and timber. And some businesses, like his film enterprises, were complete losers. To maintain his pace of borrowing, his holding companies had to continue to pay eye-popping dividends. The shadowy bridge between the grotty world of his real businesses and the golden glow of his holding companies was assembled from a tissue of exaggeration, misrepresentation, glamor, and outright fraud. That bridge could stand only so long as the bull market reigned. By March of 1932, all hopes of early world recovery had fled, the cruel deflation in security markets had shut down the channels of Ponzi finance, and accountants were pressing for the details on Kreuger’s forged Italian bonds. He was finished. Suicide may have seemed the most elegant way out.95

The contractionary shocks in the early 1930s in America were surely enough to cause a nasty recession. But to explain the extraordinary virulence of the Great Depression, we have to add the international developments that pushed the United States over the brink.