II. DEVALUING THE DOLLAR

II. DEVALUING THE DOLLAR

In the long interregnum between the presidential election and the inauguration, Hoover was at his most bullheaded—essentially on a mission to convert Roosevelt to his fundamentalist version of the gold standard. Roosevelt was at first studiously noncommittal when Hoover badgered him to make joint policy statements on banking and monetary policy, but was finally forced into uncharacteristic rudeness to cut off the conversations.4

Since Hoover’s fingerprints were all over the London conference, it was not a natural priority for Roosevelt. But as he and his advisers cast about for a monetary lever to elevate commodity prices, they hit on the London conference as a vehicle for reaching an international consensus on reflation. Their first move was to arrange for a postponement of the conference opening until June, since the White House team, although they knew they wanted higher prices, had not settled on a clear path to achieve them.5

Roosevelt’s monetary policies are best understood through the lens of the congressional farm bloc. It was possibly the country’s most influential special interest, and in 1933 its constituent industry was in desperate trouble. Opening the American prairies to intensive industrial agriculture was one of the great economic successes of the last quarter of the nineteenth century. American farmers received another huge boost when World War I disrupted competing agriculture supply chains. Farmers invested frantically to take advantage of the opportunity, and were badly overextended when the war suddenly ended and their traditional competitors came roaring back. The deflation immediately after the war ballooned the real debts of farmers who had borrowed to expand their operations during the boom. One study showed that in the first half of the 1920s, the average farm owner received less income than his hired men.6

The recovery of America’s agricultural competitors intersected with solid increases in farm productivity. Farmers had been mechanizing since the advent of the McCormick reaper in the 1860s, and were among the first to take advantage of the internal combustion engine. Henry Ford took special pains to ensure that his Model T was adapted to deep-country conditions—with independent wheel suspensions to straddle rutted rural roads, rugged parts, engine layouts designed for easy repair, and kits to help farmers repurpose the Model T as a tractor. By the mid-twenties, Ford tractors were a profitable sideline. By the 1930s, the advent of the tractor consigned ten million horses and mules to slaughter and freed up the twenty-three million acres of farmland devoted to their fodder. Although there were many exceptions, farmers with larger properties, who had mechanized and adopted modern cultivation techniques, were relatively prosperous in the late 1920s. It was the smaller, less scientific farmers who were in the deepest trouble, the paradigmatic flotsam of a technology transition.7

Agricultural economists track the farm “parity ratio”—the ratio of the indices for prices paid to farmers over the prices paid by farmers. In 1917, when American food was sustaining most of Europe, the ratio was 120 in favor of farmers. By 1921, it had fallen to only 80, but recovered to an average of 90 through the rest of the 1920s. The apparent disadvantage to farmers would have been somewhat mitigated by the falling prices and quality improvements of mass-produced manufactured goods, like automobiles, washing machines, and radios. Despite the parity gap, successful farmers were probably still seeing improvements in their standard of living.8

But farm prices took a nosedive in 1930. From midsummer of 1929 to the month that Roosevelt took office, the farm price index dropped by two-thirds—primarily the result of perversely favorable weather, but possibly also progress on mechanization. The mountains of unsold grain and cotton that pushed the Hoover farm cooperatives into insolvency crushed farmers’ parity ratios—from 92 in 1929, which farmers had complained about, all the way down to 58 in 1932. Gross farm incomes were halved.9

Unlike manufacturers, it was hard for farmers to exit a market. They generally lived on their farms, and were deeply invested in their land, their equipment, their animals, and their crops. Even the largest farmers were too small to influence their market. When granaries and meat lockers were overwhelmed with unsellable product, the rational farmer would just produce more, no matter what the price, since he had already absorbed the sunk cost. The waves of bank failures in the early 1930s were overwhelmingly in rural areas. The American political system systematically overrepresents rural areas, and did so even more in the 1930s than now. So when Franklin Roosevelt thought about monetary policy, it was primarily in pursuit of raising commodity prices and saving rural America.10

The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was passed by both houses of Congress and signed by the president after he had been in office less than a month. Its declared policy was:

to establish and maintain such balance between the production and consumption of agricultural commodities, and such marketing conditions therefor, as will reestablish prices to farmers at a level that will give agricultural commodities a purchasing power with respect to articles that farmers buy, equivalent to the purchasing power of agricultural products in the base period.11

The law was a complex blend of debt relief for farmers, financial incentives to reduce plantings, and federal purchasing to push up prices. The act carried an appropriation of $100 million, to be used to defray all expenses, including benefit payments to farmers, but also provided a “processing tax” to be levied on the first processors of any commodity slated to receive benefits under the act.*12 The bill had few fans in the Congress, mostly because of its complexity, and even its supporters understood that it would take a long time to work. So Roosevelt and one of his favorite “Brain Trusters,” Raymond Moley, investigated the possibility of jacking up commodity price levels through monetary policy, with considerable input from Henry Morgenthau, an old friend and gentleman farmer from New York, whom Roosevelt had drafted to chair the new Farm Credit Administration.

The Congress got involved in early April, pairing the AAA bill with the Thomas Amendment, named after its sponsor, a reflationist Oklahoma senator, Elmer Thomas. The amendment empowered the president to raise prices by any of a menu that included large-scale purchasing of government securities, issuing up to $3 billion in greenbacks, expanding the use of monetary silver, or devaluing the dollar. The original bill required the president to take one or more of those actions, and Roosevelt considered it a victory that the final bill had left it to his option. But the message was strong, and Roosevelt privately let it be known that he had been converted to the devaluationist camp. When that leaked in mid-April, the dollar took a steep fall, prompting celebrations in the White House and the Farm Belt. Roosevelt then secured legislation forbidding most private ownership of monetary gold and embargoing its export to prevent a flight of monetary gold from the Treasury. The practical effect was that the United States was no longer on the gold standard. If foreigners couldn’t get paid in gold, they would be forced to protect themselves by bidding up paper dollar prices. And, indeed, commodity and stock market prices rose rapidly for the next several months.13

Those events occurred as MacDonald and Édouard Herriot, leader of the French Radical party and a three-time prime minister, were separately en route to visit Roosevelt in preparation for the world economic conference. They might as well have stayed home, for Roosevelt had lost interest when he learned that forgiveness of the American war loans was one of the conference’s top priorities. He didn’t feel strongly about the issue, but there wasn’t a chance that the Congress would have stood for it. Roosevelt did give lukewarm support to a plan floated by his monetary experts to stabilize the dollar-pound-franc cross-rates, incorporating a 15–25 percent American devaluation. Neither Herriot nor MacDonald was willing to agree to such an arrangement, leaving it to the conference meetings in June.14

Roosevelt appointed a large and diverse American delegation to the conference, which was nominally led by Cordell Hull, the new secretary of state, with little policy guidance from the White House. The first order of backroom business was to negotiate a currency stabilization agreement between the British, the French, and the Americans. The chair of the monetary committee was James M. Cox, a former governor and congressman from Ohio—Roosevelt had been his running mate when Cox was the Democratic presidential nominee in 1920. Herbert Feis, a historian and economist, was an adviser to the Treasury along with James Warburg, an influential banker and a scion of the Warburg bank. Roosevelt’s former professor, Harvard’s Sprague, had been enlisted as a technical adviser to the conference working group—he and Warburg may have been the most vociferous advocates for a stabilization agreement at almost any cost. Within just a few days, the three country teams agreed on a stabilization plan. Superficially, it looked like the plan Roosevelt had signed off on at the Washington meetings, but the fine print included show-stopping provisions, like promising never to invoke the Thomas Amendment powers, and setting an uncomfortably high level for the stabilized dollar. When news of the agreement hit the press, commodity prices and the stock market duly crashed, and Roosevelt quickly rejected it. The official communique to the conference said, “The American government feels that its efforts to raise prices are the most important contribution it can make, and that anything that would… possibly cause a violent price recession would harm the conference.”15

In retrospect, it’s easy to see how Roosevelt’s position was evolving. At the right price levels, a British-French-American stabilization was a fine idea, but there was an immense gulf between the rock-hard deflationist position of the French and the reflationary yearnings of the British and Americans. Nor did Roosevelt see any urgency. The British, most of the Commonwealth, and the French, had all dropped the gold standard for periods of years, without any dreadful consequences. The United States needed time to think through its objectives, particularly since Roosevelt was convinced that getting the right prices was the main thing. Stabilizing too early could only handcuff his policy making.

At that point, Moley decided he should go to the conference, as Roosevelt had urged him to. He first met with the president, who was on a sailing vacation, for any last-minute instructions. According to the historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., they were mostly about not visibly upstaging Hull. Hull, however, was a wily politician, who viewed Moley as a self-important meddler. As he later wrote, he decided “to give him all the rope he might want and see how long he would last.” It took only a few weeks.16

Moley arrived at the conference just after Roosevelt’s stiff reaction to the original stabilization agreement had touched off a sharp fall in the value of the dollar and a correspondingly sharp rise in American commodity prices. The dollar’s fall against gold put great pressure on the “Gold Bloc,”—Belgium, the Netherlands, Poland, and Switzerland—that had adopted the French hardline deflationist monetary stance. As their currencies rose against the dollar, all of the deflationist countries’ exports collapsed, and they feared being forced off gold. Desperately, they pleaded for a stabilization agreement to preserve their commitment to gold.

What they asked for, Moley thought, was utterly innocuous—merely affirmations from the United States that they were committed to an eventual return to a gold standard with fixed exchange rates. Spooling out all the rope that Hull had supplied, Moley took over the project. Sure of his own judgment, he deftly worked out a conforming agreement, cleared it with other key Roosevelt advisers, including the deflationists Dean Acheson, the undersecretary of the treasury, and Lewis Douglas, the director of the budget, and scheduled a Downing Street press announcement, with MacDonald presiding, before he cleared it with the president.17

Roosevelt was appalled, and quickly returned a firm rejection. That note was only for his own team, who would have normally crafted a careful message for public dissemination. But the next day, while steaming home from his sailing vacation on a naval ship, Roosevelt sat down and wrote an open letter to the entire conference, but more directed to his own team, that the United States would support stabilization only after achieving adequate reflation.

In press parlance, it was a “bombshell” deriding exchange stabilization and the gold standard as “old fetishes of so-called international bankers… a specious fallacy, a tragic catastrophe.” The better goals, he went on were:

to plan national currencies with the objective of giving to those currencies a continuing purchasing power which does not greatly vary in terms of commodities and need of modern civilization. Let me be frank in saying that the United States seeks the kind of dollar which a generation hence will have the same purchasing and debt paying power as the dollar value we hope to attain in the future. That objective means more to the good of other nations that a fixed ratio for a month or two in terms of the pound or the franc.*

Most serious analysts were derisory, but by no means all. John Maynard Keynes in his newspaper column pronounced the president “magnificently right.” Winston Churchill, still ruing his 1925 fixing of a too-high parity for the pound, offered his congratulations and gratitude. “The American Navy,” he said, “has come over, as they did in the Great War, and although separate from us is steaming along the same course.”18

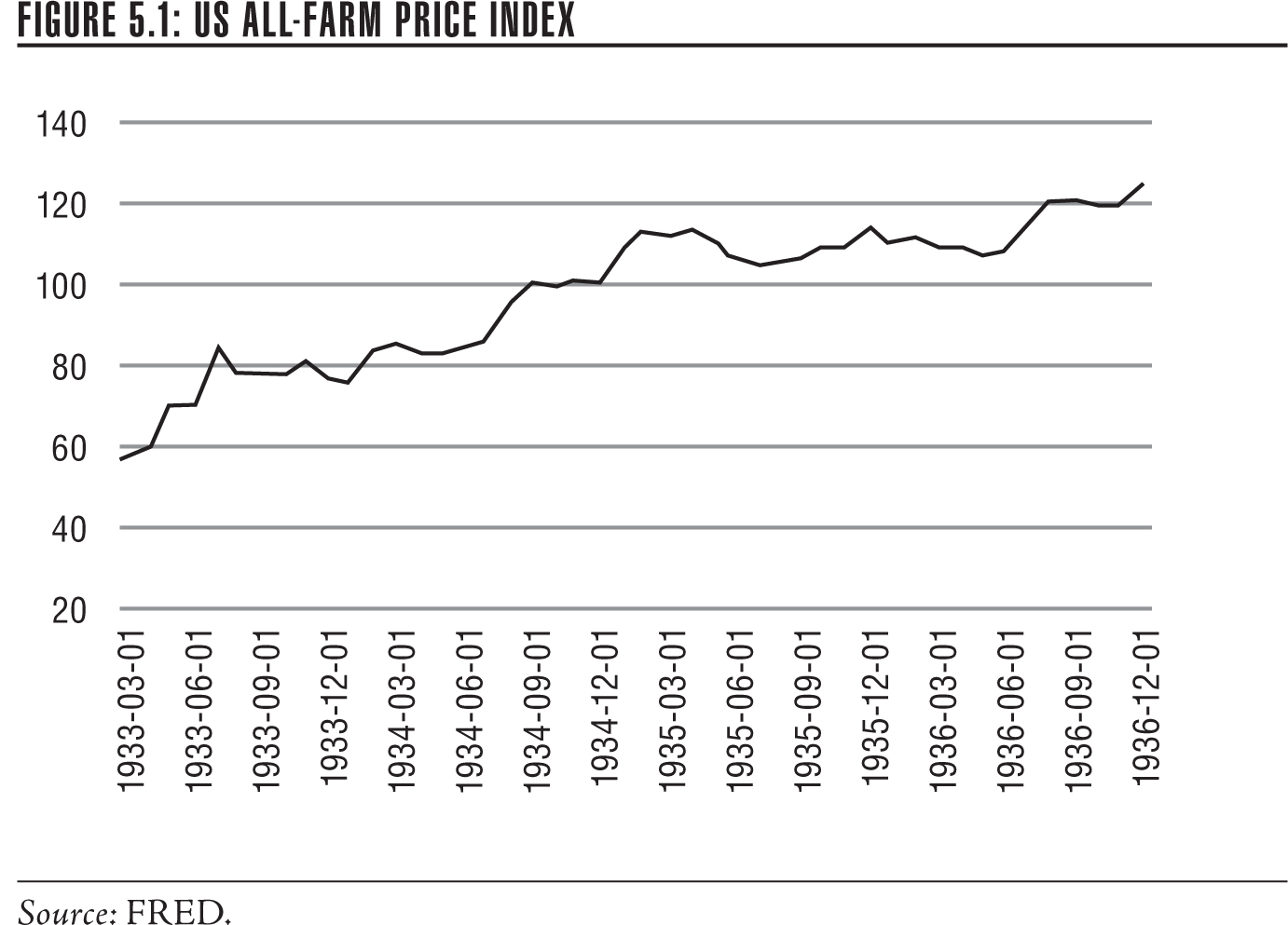

The markets reacted just as Roosevelt might have hoped. The dollar fell by 8.1 percent against the pound, and 9.4 percent against the franc. Commodity prices, which tend to be priced internationally, rose accordingly. The farm price index, which was Roosevelt’s main target, jumped by 48 percent between March and July of 1933. But when there was no immediate follow-up from the administration, commodity prices flattened out. Morgenthau then reintroduced the president to a Cornell agricultural economist, George F. Warren. Morgenthau had chaired a New York State Agricultural Advisory Commission when Roosevelt was governor. He had been very impressed by Warren, one of the commission’s experts, and had included him in a number of meetings with the governor.19

Warren is often portrayed as something of a crank, peddling economic snake oil of a kind that the amateurish Morgenthau and Roosevelt were particularly susceptible to. He and a former graduate student, Frank A. Pearson, had spent more than twenty years working up statistical compendia of rural production and prices, which they gradually extended both backward in time and laterally to nonagricultural commodities.* Along the way, Warren became convinced that there was a close inverse association between commodity prices and the price of gold: when the price of gold fell, usually because of new discoveries, commodity prices rose and vice versa. It was a claim that seems to have particularly offended bankers and economists.

Elmus Wicker, a leading authority on the Federal Reserve, stated flatly in 1971 that, “Whatever the statistical shortcomings of the data or its interpretation, the observed relationship between the supply of gold, the growth of physical volume of production, and the price level is without causal significance.” The great economist and student of crises, Charles Kindleberger, was similarly caustic, although he grudgingly agreed that because of “serendipity,” and despite the fact that “Roosevelt and his closest advisors… often had no clear idea what they were doing,” in the end “the policy may have been a good one.”20

As it became clear that Roosevelt was paying attention to Warren—the two men had a number of private meetings—the president’s official economic advisers became alarmed. At the pleading of Acheson and Warburg, Roosevelt convened an economic policy group that met without Warren, who was in Europe. Wicker deplores the fact that no one attacked the weaknesses in Warren’s proposals, the most glaring of which was that the alleged relationship did not hold through most of the 1920s. Roosevelt had charged the Acheson-Warburg group to show him how to raise commodity prices. Instead, they wrote a report recommending international cooperation—in effect, the strategy of the recently trashed Monetary and Economic Conference. One can imagine the glaze spreading over the president’s eyes. Warren, almost by default, became a key revaluation advisor.†21

In October, Roosevelt and Morgenthau began a cautious experiment to raise the price of gold by placing bids through the RFC, which was authorized to purchase commodities. Before actually making any purchases, on October 22, Roosevelt had a fireside chat, announcing to the country that “ever since last March the definite policy of the Government has been to restore commodity price levels.” To do that would require revaluing the dollar. “I would not know, and no one else could tell, just what the permanent value of the dollar will be,” but it was time the country took “firmly in its own hands the control of the gold value of our dollar.”22

The first purchase was delayed for several days by Acheson’s truculent foot-dragging, effectively his act of hara-kiri. An angry Roosevelt announced Acheson’s resignation to the press without warning him. Acheson, ever unflappable, showed up at the swearing-in of his successor, delighting the president with “the best act of sportsmanship I’ve ever seen.” Acheson was brought back into the administration in 1941 as an assistant secretary of state, both a tribute to his obvious talents and no doubt to his sportsmanship—both Roosevelt and Acheson were Groton boys who had learned the rules of right behavior from its long-time headmaster, Endicott Peabody.23

Morgenthau, Roosevelt, and the chairman of the RFC, Jesse Jones, met frequently to set the gold dollar prices. The first purchase was at $29.01 on October 21, and by the end of the year, prices had crept up to $34.06. At that point, Roosevelt decided to fix the price at a round $35, just short of a 60 percent increase over the old price of $20.67 per fine ounce. One important detail was what to do with the $2.8 billion profit from the revaluation of the US gold reserves. It was finally decided to transfer the reserves from the Federal Reserve to the US Treasury, with most of it earmarked as a stabilization fund, in effect a war chest to fend off future attacks on the currency.24

The early returns from the gold-buying activity, in fact, had been disappointing. The dollar price of gold drifted up in rough conformity with the RFC’s prices, and American exports showed modest improvement, but there was no substantial improvement in commodity prices—indeed prices fell in parts of November and December. The problem was that traders were confused by the unpredictable changes in the dollar’s value—it made them cautious, rather than bullish. Once the president announced that the experimentation was over, however—that $35 was the final number—a strong commodity boom got underway. American exporters started shipping the orders they had delayed until the currency was settled; importers that had overbought to lock in lower prices reduced their buying programs; currency traders that had sold dollars covered their positions and took their profits.25

It was more than fifty years after Roosevelt’s action on the dollar before economists recognized the benefits of devaluing a currency in an economic crisis. Currency depreciation had been classified with trade restrictions as beggar-my-neighbor policies—designed to shift incomes to the country imposing the change—and therefore were universally dismissed or condemned by orthodox opinion. While both strategies usually stimulated the economies of the initiating countries, retaliatory actions by other countries, it was thought, typically reduced incomes all around. Two landmark papers by Barry Eichengreen and Jeffrey Sachs showed that, unlike trade restrictions, currency devaluations did not necessarily have adverse consequences. It all depended on the policy details: in principle, a properly managed devaluation could have win-win outcomes for all. For example, if Country A devalues, its imports will become expensive, its exports will boom, and as its businesses revive, incomes will rise. It’s easy to see that those policies could hurt its trading partners, but with careful management, the stimulus in Country A will create more opportunities for its trading partners and trigger a virtuous circle of growth.26

To get the most out of a devaluation, it is critical that the monetary benefits are used to promote growth. The United States, recall, earned a $2.8 billion markup profit when it raised the price of gold. That could have been pumped into bank reserves to juice up spending, or if the private sector was too shell-shocked to borrow, it could have funded an infrastructure program without a tax or debt increase. Instead it was plunked into a stabilization reserve that was almost never used. In fact, all of the major devaluations, from the 1931 British one on, appear to have considerable beggar-my-neighbor effects, although they were mitigated to the extent that other countries eventually devalued as well.27

The United States didn’t entirely waste its opportunity. The initial devaluation prompted a flood of gold into the country, $650 million worth, mostly from traders that had bought gold in anticipation of its revaluation and were now switching back into dollar instruments. But the river of gold continued to flow, as fears of Hitler’s increasing sway over Germany triggered waves of flight capital. Gold was high-powered money, so it directly increased American spending power. It obviously would have increased it more, as Eichengreen argues, if the Fed had multiplied the gold trove by using it to support currency issuance and deposit expansion.28

Finally, a historical footnote: in the first of their two landmark papers, Eichengreen and Sachs tip their hats to George Warren and Frank Pearson for being the first to “document the relationship between exchange depreciation and relative price levels and outputs.” Warren may have been disappointed that the relationship was not as mechanical as he supposed, or as his pre-1914 data had suggested, but it was there nonetheless, and Roosevelt’s “milk farmer,” as Acheson called him, made a real contribution to the recovery.29