V. THE NEW DEAL IN DETAIL

V. THE NEW DEAL IN DETAIL

In early April 1933, Fiore Rizzo and three other young men pulled up in a taxi at an army recruiting station in lower Manhattan. The taxi fare was 65 cents, but the four had only 50 cents between them, so an army captain put up the difference. Rizzo was nineteen and single, from a family of thirteen children. He had been unemployed for a year, and his father had been unemployed for three years. By chance, he was the first registered recruit for the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Rizzo had a brief physical, took an oath, signed a form authorizing the government to pay his family $25 of his $30 a month pay, and was shipped off to an upstate training center for two weeks’ of training and conditioning. From there he would be assigned to a six-month stint in the National Forests planting trees, clearing brush, working roads, building fire controls, and fighting insect pests. The CCC director expected Rizzo to be assigned to Tennessee because it was “already warm there.” “Most of the men called,” he said, “will be off the bread line. The work will not be intensely laborious—but it will be work.… There will be no military features in connection with the camps.”42

The CCC was part of a package of work relief and income grants that were a focus of the Roosevelt Hundred Days legislative program. The fact that it was up and running in little more than a month after the inauguration is impressive, and was possible only because Roosevelt had the sense to turn the job of creating and administering the camps to the army. Colonel George Marshall set up seventeen of them. It may have been Roosevelt’s favorite program—he made a point of visiting the camps whenever his schedule took him by one, and he mused about making it a permanent establishment. He was a conservationist by inclination and by family ties. As governor of New York, he created a forestry and tree-planting program with slots for 10,000 unemployed men.43

Thirteen hundred CCC camps were up and running by mid-June, and by mid-July, they had enrolled and deployed 300,000 men. Altogether 2.5 million went through the camps, most of them staying for six months to a year, with the high point of enrollment at 500,000 in July 1935. There were usually some dropouts among each new batch, because of the strangeness of the surroundings and the quasi-military discipline, but most enrollees seem to have viewed it as a life-changing experience—many had never been out of their neighborhood, much less lived in a forest. They also learned simple trades, like driving a truck, laying stones, and mixing concrete. Exit interviews were mostly positive—“I weighed about 160 pounds when I went there and when I left I was 190 about. It made a man of me all right.” And “if a boy wants to go and get a job after he’s been in C’s, he’ll know how to work.”44

CCC was a great showpiece, but the more pressing requirement was for financial relief for unemployed families. The Hundred Days legislative program included both the Federal Emergency Relief Agency (FERA) and the Public Works Administration (PWA). FERA was run by Harry Hopkins, perhaps Roosevelt’s best manager. (Winston Churchill later dubbed him “Lord Root of the Matter.”) FERA had great flexibility—it could give “direct relief,” effectively the dole, but “work relief” was the priority. Most work relief was for low-end jobs—“leaf-raking” in common parlance, with frontline management from local governments. Work relief paid stipends that were about half the pay normally received by low-end workers, and was much preferred over the dole.45

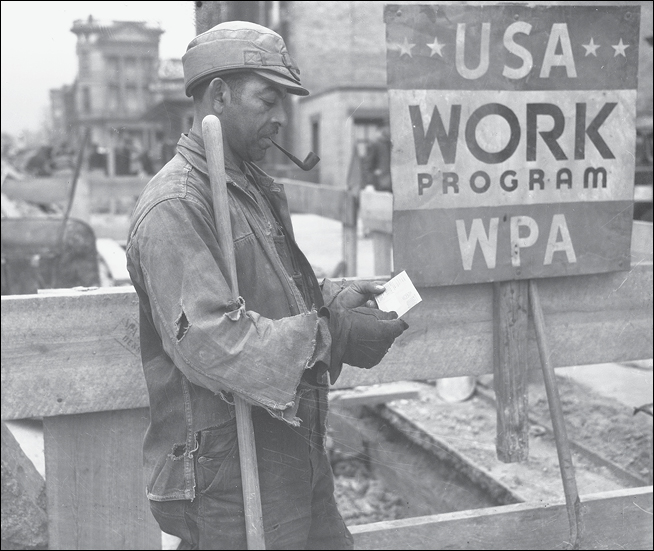

The fall of 1933 was the first of the New Deal, but it was the fourth year of the Great Depression. Unemployed workers and their families were demoralized, and some were joining “unemployment leagues,” many of them organized by Communists, like Louis Budenz. Hopkins lobbied Roosevelt to let him run a short-term winter program, of approximately four months, to hire four million people for work projects at full civilian pay. Starting virtually from scratch in mid-November, he had 2.6 million people on the CWA payroll by mid-December, and four million by mid-January. (He apologized profusely for missing his target.) About a third of his workers repaired or surfaced roads, but others built or improved 40,000 schools, cleaned up parks, dug sewer lines, and cleared industrial canals. The evidence is that much useful work was completed, but given the sheer numbers of people engaged, there was a great deal of wasted effort, and complaints of men getting paid for leaning on shovels all day. (The prominence of shoveling, however, stemmed from a Hopkins policy decision. The main purpose of work relief was to create work, so Hopkins banned most modern machinery from the work sites. Sewers were dug by hand because it took longer.)46

Hopkins was imaginative—hiring 3,000 artists and writers to ply their trades as CWA workers, and paying for 50,000 laid-off teachers to return to their schools. The speed of the launch was conducive to political interference and corruption, much to Hopkins’s chagrin, and he hired army officers to clean up his processes. A senior West Point officer, however, was greatly impressed: “Mr. Hopkins’s loose fluidity of organization was justified by the results achieved. It enabled him to engage for employment in two months nearly as many persons as were enlisted… during our year and a half of World War mobilization.” The officer’s praise was warranted: for all the pratfalls, FERA and CWA distributed more than $23 per US resident in the year beginning July 1933, equivalent to almost 3 percent of the 1929 GDP, and more importantly, over 5 percent of the depressed 1933 GDP.*47

Roosevelt’s right-hand man, Harry Hopkins, was a brilliant organizer and performed prodigies creating millions of jobs for the unemployed. In truth, much useful work was done, and the employment programs were life savers for millions of families.

The other major public works spending program was the PWA, run by Harold Ickes. Both Roosevelt and Ickes insisted it was not a relief program, but rather an investment in high-quality public infrastructure. Since there were only a few shovel-ready projects at the start of the program, it took a while before there were visible results, and the delay was extended by Ickes’s insistence on personally reviewing each contract. (Because of the slow start, Hopkins was able to fund his CWA with unused PWA funds.) Hoover had greatly accelerated public work grants to state and local governments, and had also accelerated the Army Corps of Engineers’ river and harbor works, but Roosevelt and Ickes ratcheted up the Hoover commitments by several notches. The PWA, in fact, made a major contribution in shoring up the country’s public investment—highways, sewage and water systems, power plants, schools and other public institutions, docks and tunnels, ships for the US Navy, and the biggest public program of them all, the Tennessee Valley Authority. During its life, PWA spent an annual average of $3.50 per US resident, not including three years of spending an additional 41 cents per capita on public housing.48

Roosevelt’s honeymoon period lasted for perhaps a year and a half. He had come into office with thumping majorities in both houses of Congress, amid widespread fear that the country was coming apart. By the spring of 1934, although the Depression was far from ended, there were clear signs of recovery. Industrial production was up by almost half over the previous spring, and over the full year, the economy racked up 10.8 percent real growth. Unusually, the 1934 mid-term congressional elections, instead of trimming Roosevelt’s majorities actually added to them, giving him a two-thirds majority in both houses. Possibly because of their big majorities, however, the new Congress was more obstreperous. Southern and Midwestern Democrats were closer to the business view of federal spending than they were to Roosevelt’s. Most state governors were happy to see increased relief spending, but almost all of them wanted more control, and all of them had been offended by Hopkins’s insistence on his right to approve or veto projects, to allocate funds, or, as he chose to do in seven states, to federalize uncooperative state relief administrations. The Southern congressional coalition, in particular, always hypervigilant against breaches in the post-Reconstruction regime of white dominance, was upset at Hopkins’s racial blindness in distributing aid.

New Deal historians talk about the “First” and “Second” New Deal, with the break somewhere in late 1934. The relief programs were significantly reorganized, with a common theme of limiting federal discretion. FERA was disbanded, and there was a major reorganization of the income relief components. Four programs—OAA, or assistance to poor elderly; AB, or Aid to the Blind; and ADC, or Aid to Dependent Children; plus UI, or unemployment insurance—were handed over to state administration, although the lion’s share of the funding was still federal, with funding allocations by strict legislative formula. The Works Progress Administration (WPA), the new name for Hopkins’s work relief programs remained federally administered, since it was due for an early shutdown. OASI, or Old Age and Survivors’ Insurance—the basic senior retirement program—of course, was entirely federal.49 Roosevelt, over the protests of friends on the left, insisted that both Social Security and unemployment insurance be funded with contributions both from workers and employers. When an economist warned of the deflationary dangers of a new payroll tax, Roosevelt retorted that it wasn’t about economics:

[T]hose taxes… are politics all the way through. We put those payroll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their pensions and their unemployment benefits. With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever scrap my social security program.*50