VII. ECONOMETRIC ANALYSES

VII. ECONOMETRIC ANALYSES

Within the past couple of decades, scholars have performed a number of detailed econometric studies of the impacts of specific New Deal programs, with the main findings summarized here.

Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) The debt-fueled 1920s housing boom was brutally reversed early in the Depression. Average home prices fell by 30–40 percent, and as unemployment spiked to a previously unheard-of 25 percent, the HOLC was created to mitigate the impact on homeowners “in hard straits largely through no fault of their own.” The HOLC was created to purchase troubled mortgages from lenders and to replace them with direct federal loans with easier payment schedules. In the 1920s, housing finance was usually provided by specialized lenders who required a 40–60 percent down payment, five years of steep interest payments, and a balloon payoff of the principal at the end of the term, usually by a refinancing. In addition, in most conurbations “building and loan societies” provided loan terms closer to those of modern loans—with flat amortization of interest and principal—to members who had amassed enough savings for a 20–30 percent down payment. HOLC loans generally had 15-year level payment amortizations at 5 percent interest, about 1–2 percent lower than a building society loan, and much less than the rates charged by specialized mortgage lenders.57

The HOLC loans had an average principal of about $3,000, with the bulk of the refinancings in 1934. All of them were troubled loans. The typical refinancing replaced a loan that was two years in default of payments, with tax delinquencies stretching out even longer. Many states had legislated foreclosure moratoria, and even if they hadn’t, the resale market was so desolate that lenders saw no point in foreclosing. An indication of the depths of the housing market is that HOLC turned down nearly as many applications—800,000—as the million it approved. If nothing else, therefore, the HOLC made a major cash infusion to a broad range of lending institutions.

HOLC terms were generous: they often valued a home value at the pre-Crash price, and added reconditionings and tax delinquency payoffs to the primary mortgage. By 1936, 39 percent of their portfolio was nonperforming, and they ultimately foreclosed about half that number. Between 1936 and 1940 HOLC owned and sold off some 2 percent of the nonfarm dwellings in the country.

Price Fishback and his colleagues, in a 2010 paper, attempted to measure the housing market benefits of HOLC. Roosevelt officials had, logically enough, evaluated HOLC by regressing (measuring the relationship between) increases in home values and home ownership with local HOLC expenditures. The results were positive—impressively so. The stunner was that an extra $1 per capita in HOLC expenditures was associated with a $51 increase in home values.

It was a mirage. Statistical analysis has made huge strides since the 1940s, and simple regressions are no longer conclusive, unless the analyst separates all the factors that may bear on a result. The apparent HOLC results were skewed because loans were disproportionately distributed to areas with higher home values and ownership rates. Deeper analyses suggest that HOLC may have been associated with declines in home values and ownership levels and reductions in rents and increases in rentals, although the correlations are weak. There were, however, substantial positive results in counties with less than 50,000 people: HOLC spending was associated with increases in home values and home ownership at a 10 percent level of statistical significance. Those results make intuitive sense: rural areas generally had poor access to full-service financial institutions, so HOLC loans would have filled a real need.

After the last HOLC loan was paid down in 1951, and the agency closed down, the Treasury estimated its losses at about $78 million, which the Fishback group says could have been as high as $100 million, or about 3 percent of the amount lent, although the cash losses were only about half as much. That seems a small price to pay for a critical infusion of cash into credit markets. Investment had collapsed in 1933 and 1934, so there could be no concerns about crowding out more productive lending. The possibility of a death plunge in the housing market was all too real, so solely for its preventive effects, HOLC must be counted as a good investment.

Welfare, Work Relief, and the AAA Another Fishback-led paper examined the impact of the administration’s relief spending, including both welfare payments and pay for work relief under various New Deal programs—FERA, WPA, PWA, and CWA, as well as programs sponsoring public roads and public housing. A number of neoclassical economists were convinced that such spending might actually decrease employment.58

The Fishback team analyzed the effect on retail sales in every county that received the various forms of direct relief and work relief, as well as the benefits of the AAA, using an arsenal of modern statistical techniques to filter out false signals. The results for the relief programs were unambiguous. One dollar of public relief or work relief raised retail sales in 1939 by 44 cents. Since retail sales on average consumed nearly half of household incomes, that suggests that one dollar of relief spending raised local incomes by about 83 cents.

Counties receiving AAA funds on average showed the opposite result, since most of the AAA grants were designed to take crops out of production. It was the landowners, after all, who were the object of concern for the farmers’ lobbies. Production limits raised farmers’ incomes at the price of reducing incomes for farm laborers and sharecroppers. The loss of incomes at the lower end of local populations apparently matched, or slightly outweighed, the incomes gained by farm owners. For good or for ill, that is, both the relief spending and AAA grants accomplished what they set out to do.

A follow-up study looked specifically at the notion that the relief programs reduced private employment opportunities. Using panel data from forty-four cities, the analysts showed that in the First New Deal (1933–1935), the increase in relief programs increased private employment, doubtless because of their impact on local spending power. The impacts were different during the Second New Deal, 1936–1939, however, because the contexts had shifted. Direct relief (welfare) programs had been turned over to the states, but the WPA programs were still run out of Washington. The more important change was that, by 1939, real economic growth had returned per capita GDP back to its 1929 level. Companies were hiring, and unemployment, although still too high, was considerably lower. And the analysis bears out the complaints of employers that WPA employment made it more difficult to fill positions. That would have surprised the WPA managers, for their jobs deliberately paid about half the wage available in private employment, and a WPA worker could be terminated for refusing a private job offer. The explanation, apparently, is that private sector jobs were still viewed as uncertain, with a constant possibility of layoffs. As one WPA worker put it: “Why do we want to keep these jobs? Well… we know all the time about persons on direct relief… just managing to scrape along.… My advice, buddy, is better not take too much of a chance. Know a good thing when you got it.” In other words, the risk of being laid off and having to resort to welfare, with lower stipends than the WPA, was not worth it. We’ll come back to the unemployment conundrum below.59

That same study also looked at the allegations that the Roosevelt administration was buying votes with its relief programs. Harry Hopkins had, if only allegedly, but still famously, disclosed the Roosevelt formula for success: “We shall tax and tax, spend and spend, and elect and elect.” The analysts found, however, that program distribution was matched closely to need. Severely impacted Democratic areas did not get notably more aid than similarly impacted Republican areas, although it was true that local relief spending was higher in election years. An older study, however, by Gavin Wright, showed that, in principle, there was a game-theoretic approach to influence voting while still maintaining the focus on seriously impacted areas. The trick was to supply additional funds when Democratic majorities were in flux, and modest amounts of extra federal money might help achieve a critical majority. In the 1936 and 1938 elections, there was indeed evidence of such fine political tuning of the outlays. With Jim Farley’s hand on the political steering wheel, it would have been almost disappointing not to find any manipulation.60

There were a number of ancillary positive effects of federal relief in poor areas. A relief infusion of $2 million was associated with a reduction of one infant death, one suicide, 2.4 deaths from infectious diseases, and one death from diarrhea. A 10 percent increase in work relief saved 1.5 property crimes, although a 10 percent increase in private employment had a much larger effect, virtually one to one.61

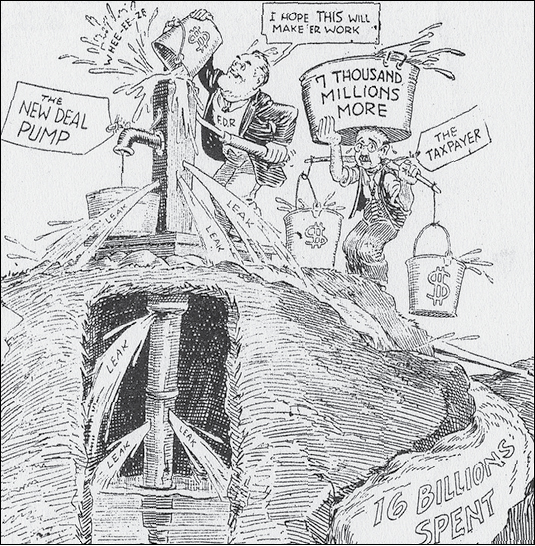

The New Deal was always a messy operation. It had to be—there was no consensus on what had gone wrong, and even less on what to do about it. But the deflation gauntlet had been so demoralizing and destructive that throwing money at the problem was not a totally crazy idea. And throw money the New Deal surely did. From 1934 through 1936, federal debt as a share of GDP rose from 16 percent to 40 percent. Despite the oft-told tale that Keynesian stimulus was barely tried in the Depression, the official budget deficits, plus the off–balance sheet borrowing of entities like the RFC and the HOLC, brought the annual increase in federal liabilities during 1934–1936 to an average 8.5 percent of GDP, a powerful kick. Monetary policy also played a major role, from the dollar devaluation and the Treasury’s permissive attitude toward monetizing gold inflow from Europe and Japan. The results were clear—a three-year real growth rate of 8.7 percent.62 Then, in mid-1937, something happened.

No peacetime president had ever spent the immense amounts that Roosevelt did in attempting to reverse the Depression. When Roosevelt prematurely pulled back on the spending, the economy crashed almost immediately, and recovery came only when most of the programs were revived.